Highlights

-

•

Incarcerated appendicitis could be due to an unexpected inflammatory etiology.

-

•

Elucidating the etiology of inflammation is essential for directing management.

-

•

Ongoing inflammatory process after appendectomy may be due to Crohn’s disease.

-

•

Laparoscopic management of perforated hernial appendicitis provides excellent visualization.

Keywords: Appendicitis, Crohn’s, Ventral/incisional hernia, Achondroplastic dwarfism, Colocutaneous fistula, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Incidence of hernial appendicitis is 0.008%, most frequently within inguinal and femoral hernias. Up to 2.5% of appendectomy patients are found to have Crohn’s disease. Elucidating the etiology of inflammation is essential for directing management.

Presentation of case

A 51-year-old female with achondroplastic dwarfism, multiple cesarean sections, and subsequent massive incisional hernia, presented with ruptured appendicitis within her incarcerated hernia. She underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, appendectomy, intra-abdominal abscess drainage, and complete reduction of ventral hernia contents. She developed a nonhealing colocutaneous fistula, causing major disruptions to her daily life. She elected to undergo hernia repair with component separation for anticipated lack of domain secondary to her body habitus.

Her operative course consisted of open abdominal exploration, adhesiolysis, colocutaneous fistula repair, ileocolic resection and anastomosis, and hernia repair with bioresorbable mesh. She tolerated the procedure well. Unexpectedly, ileocolic pathology demonstrated chronic active ileitis, diagnostic of Crohn’s disease.

Discussion

Only two cases of hernial Crohn’s appendicitis have been reported, both within Spigelian hernias. Appendiceal inflammation inside a hernia sac may be attributed to ischemia from extraluminal compression of the hernia neck. This case demonstrates a rare presentation of multiple concurrent surgical disease processes, each of which impact the patient’s treatment plan.

Conclusion

This is the first report of incisional hernia appendicitis with nonhealing colocutaneous fistulas secondary to Crohn’s. It is a lesson in developing a differential diagnosis of an inflammatory process within an incarcerated hernia and management of the complications related to laparoscopic hernial appendectomy in a patient with undiagnosed Crohn’s disease.

1. Introduction

Incidence of hernia sac appendicitis has been reported as 0.1% and perforated appendicitis within a hernia as 0.008%, most frequently within inguinal and femoral hernias [2]. Appendiceal inflammation inside a hernia may be due to ischemia from extraluminal compression of the hernia neck or trauma from peri-appendiceal adhesions [1].

Elucidating the etiology of appendiceal inflammation is essential for directing management. While emergent appendectomy is the standard of care for appendicitis, non-operative medical management is appropriate in cases of inflammatory bowel disease. Up to 2.5% of appendectomy patients are found to have Crohn’s disease [3] and 34–58% of patients who undergo appendectomy without ileocecectomy, develop complications associated with Crohn’s disease, like enterocutaneous fistula, necessitating further surgical management [2].

Only two cases of hernial Crohn’s appendicitis have been reported, all within Spigelian hernias [3], [5]. Here we describe the first reported case of Crohn’s appendicitis within an incisional hernia.

This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria.

2. Presentation of case

A 51-year-old female with history of achondroplastic dwarfism, morbid obesity (BMI of 46), multiple cesarean sections, and subsequent massive incisional hernia presented to the emergency department after one week of nausea, bloating, intermittent vomiting, fever, and diarrhea. On evaluation, she was tachycardic, febrile, and displayed tenderness on palpation of her lower abdomen over her ventral hernia with corresponding areas of cellulitis. Furthermore, her laboratory values were notable for a leukocytosis of 16,000. Computed tomography scan demonstrated a dilated appendix with appendicoliths, thickening of the neighboring small bowel walls with fat stranding, and two adjacent abscesses, consistent with ruptured appendicitis within her incarcerated ventral hernia (Fig. 1). Given that the patient’s septic status and the extent of the multiple abscesses tracking through the hernia sac compromising the surrounding incarcerated small bowel, the decision was made to proceed with surgical drainage and appendectomy. Intravenous antibiotics were initiated in the emergency department and sustained during the operation. Intra-operatively, she underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, laparoscopic access into the hernia sac, releasing 550-cc of purulent fluid with necrotic tissue, which was drained and washed out, followed by appendectomy, and complete reduction of the hernia contents. The patient’s body habitus made for limited abdominal domain and increased the difficulty of the operation. The small bowel and cecum appeared hyperemic, but viable and without obvious pathognomonic evidence of Crohn’s disease.

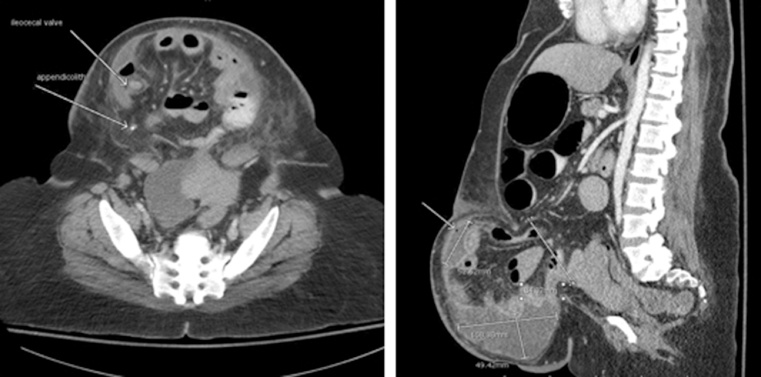

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan of abdomen and pelvis. Large, broad-based ventral hernia (8.4-cm × 5.9-cm) containing ileum, cecum, appendix, and some ascending colon, with dilatation of proximal small bowel loops without passage of contrast into normal caliber exiting loops of colon, concerning for high grade small bowel obstruction. Within the hernia sac, the appendix is slightly dilated to 7.5 mm, with two appendicoliths found within the lumen. The bowel walls within the hernia sac are thickened, with prominent fat stranding. There are two adjacent fluid collections, measuring 10.8 × 4.9 × 10.4-cm and 1.4 × 3.8 × 5.2-cm, containing locules of gas, suggestive of abscess.

Pathologic analysis of the appendix showed acute and organizing serosal and subserosal inflammation with sparing of the mucosa. Mucosal inflammation would be expected in the normal pathogenesis of ruptured appendicitis progressing from bacterial invasion to ischemia and gangrene; therefore, the pathology and surgical team deduced that the periappendicitis was the result of an extrinsic inflammatory process, likely associated with incarceration at the hernia neck. While evidence of perforation and lymphocytic invasion was evident on the appendiceal pathology, there were no epithelioid granulomas, mucosal ulcerations, serosal fibrosis, or transmural inflammation, as typical of Crohn’s appendicitis. The patient’s post-operative course was unremarkable, except for mild ileus which self-resolved.

The patient returned two years later with purulent drainage from her anterior abdominal wall. She was found to have two connecting abscesses within the hernia sac, requiring multiple readmissions for incision and drainage and intravenous antibiotics (Fig. 2). After five months of ongoing drainage, she underwent an upper gastrointestinal barium follow-through study, which demonstrated an enterocutaneous fistula at the hernia apex (Fig. 3). A wound manager was employed while allowing the fistula to mature, with plans for eventual surgical intervention. The cumbersome nature of her large hernia and the continuous, uncontrolled fistula output caused major disruptions to the patient’s daily life. She elected to undergo fistula takedown and hernia repair with potential component separation for anticipated lack of domain secondary to her diminutive body habitus with protuberant hernia and her achondroplasia.

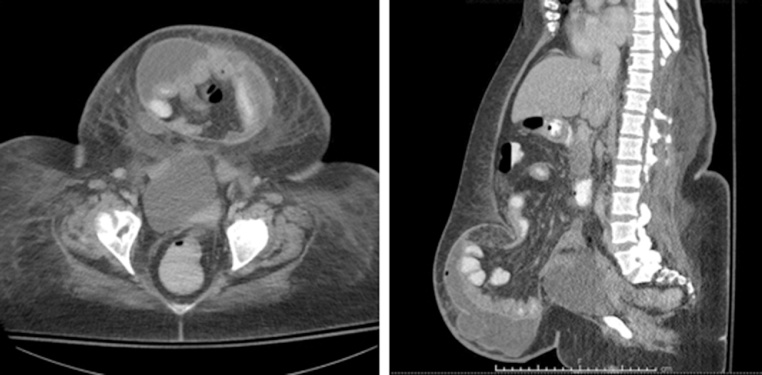

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography scan of abdomen and pelvis. Ventral hernia with wide neck (6.6 × 6.0-cm), containing multiple loops of small bowel, including the cecum. No evidence of obstruction or dilated loops of bowel. Thickening present of the bowel wall along the terminal ileum. A localized fluid collection is seen within the subcutaneous fat between the skin surface and the hernia sac, measuring 10.0 × 9.0 × 3.0-cm.

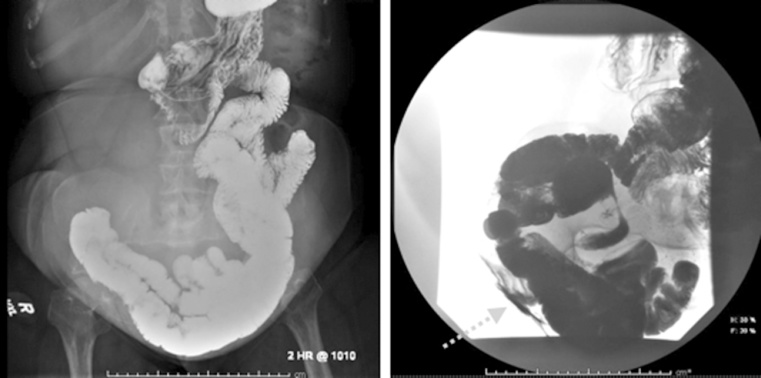

Fig. 3.

Barium gastrointestinal follow-through study. Contrast advanced through the small intestine without delayed progression. At three-hours, barium to opacified the upper- and mid-small bowel, terminal ileum, and right colon, with cutaneous contrast extravasation overlying the right lower quadrant anteriorly, at the apex of a large ventral hernia.

Her operative course consisted of open exploration, adhesiolysis, colocutaneous fistula and ileocolic resection, and primary anastomosis. The fistula tract was traced to the location of the appediceal stump closure. The edges of the hernia defect were approximated in the midline without tension over Phasix™ ST Mesh (Bard, Davol Inc.) in sublay fashion. A bioresorbable mesh was chosen to minimize the risk of infection in this contaminated case, while providing greater duration of wound support than a biologic mesh. It was deemed appropriate to forego an anterior component separation, which would be associated with an increased risk of wound complications, especially surgical site infection. The patient tolerated the procedure well. She resumed a regular diet on post-operative day three and was discharged home on day nine. Unexpectedly, pathology demonstrated chronic active ileitis, diagnostic of Crohn’s disease.

Despite the use of drains in the subcutaneous space, the patient developed a superficial abscess that was managed with open drainage (Fig. 4). She subsequently did well; at six months, she reported a significant improvement in her quality of life.

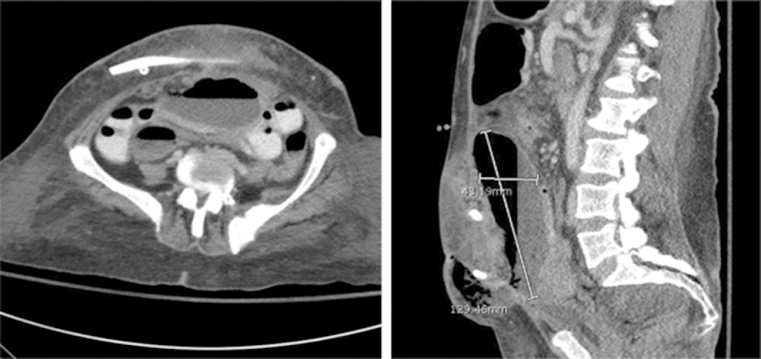

Fig. 4.

Computed tomography scan of abdomen and pelvis. Large fluid collection (12.3 × 9.6 × 4.7-cm) with air-fluid level identified within the anterior abdomen and pelvis, extending through the anterior abdominal wall musculature into the subcutaneous fat of the anterior abdominal wall. A Jackson-Pratt drain is present within the subcutaneous fat of the anterior abdominal wall, surrounded by diffuse stranding.

3. Discussion

This case demonstrates a rare presentation of multiple concurrent surgical disease processes, each of which impact the treatment plan for the patient. Incarcerated appendicitis is most commonly attributed to strangulation of the mesenteric vascular pedicle at the hernia neck or to the presence of a fecolith [2], [7]. While it is possible that both of these etiologies contributed to the patient’s initial presentation, the complicating diagnosis of Crohn’s disease discovered on subsequent ileocecal resection may very well have been the cause. Only two cases of incarcerated Crohn’s appendicitis have been reported [3], [5]. Our patient represents the first known report of appendicitis within an incisional hernia later presenting with non-healing colocutaneous fistulas secondary to Crohn’s disease.

The finding of hernial appendicitis is a rare event, with the overall incidence reported as 0.1% and perforated appendicitis as low as 0.008%; though the estimated incidence specifically of inguinal hernia appendicitis is 0.07–0.13% [8], [9], [10]. A comprehensive review of hernial appendicitis reported a bimodal age at presentation, with peaks at 37 days old and 69 years old, corresponding to the normal distribution of perforated appendicitis, but inversely correlated to acute appendicitis [7]. Flood et al. described a correlation between hernial appendicitis and the size of the hernial orifice [11]. Futhermore, hernial appendicitis presented more often at an advanced stage due to delayed systemic manifestations with isolation of the infectious process to the hernia sac, as well as due to the low index of suspicion of appendicitis as the cause of inflammation within the hernia [1], [6].

Early surgical intervention is considered the accepted management of complicated appendicitis to reduce morbidity and mortality compared to non-surgical treatment modalities [12]. Operative intervention was indicated for this patient as she presented in sepsis with evidence of rupture on CT scan, including extensive fluid tracking within the hernia sac and inflammatory changes to the surrounding bowel and mesentery, conferring a diagnosis of complicated appendicitis [13]. While multiple meta-analyses of large trials have investigated the efficacy and durability of antibiotic treatment of acute appendicitis in lieu of operative management, only cases of non-complicated appendicitis were included. Regardless, these reports have concluded that compared to antibiotics-only groups, surgical therapy results in a significantly higher efficacy rate at 1 year, equivalent length of hospital stay, sick leave, and post-hospital symptom duration, and has been recommended as the definitive treatment of acute appendicitis [12], [14], [15]. While laparotomy with washout and appendectomy has been the standard of care for the surgical management of perforated hernial appendicitis, [16]; more recent reports describe the safety and advantages to laparoscopy [9]. The laparoscopic approach proved beneficial for our patient, as it simultaneously allowed excellent visualization of her intra-abdominal contents, including the viability of the bowel within and on ingress into the hernia sac, reduction of the hernial contents, comprehensive peritoneal washout, and appendectomy, without incurring the additional morbidity of a large herniotomy.

Also essential to the determining the patient’s management was discerning between appendiceal Crohn’s disease and acute appendicitis. This may prove challenging in the patient who first presents with right lower quadrant pain or an acute abdomen. Between 0.2 and 2.5% of appendectomy patients have been found to have Crohn’s disease across multiple series [4], [5], [17]. Twelve to 16% of patients with Crohn’s disease who have ileal involvement and 20–50% with colonic involvement present with the inflammatory process extending to the appendix [18], [19]. About 85% of patients with appendiceal Crohn’s present with acute abdominal pain in the right iliac fossa, similar to classic appendicitis symptoms [5], [16].

While appendicectomy and ileocecal resection are both considered acceptable management for Crohn’s appendicitis, up to 58% of patients who undergo appendectomy alone go on to develop Crohn’s-related complications [5] In a retrospective review of 1421 patients with Crohn’s who underwent exploration for presumed appendicitis, 92% of patients who underwent appendectomy required additional surgery for further complications, compared to only 50% who underwent ileocecectomy [19]. The tenet of Crohn’s management is limiting surgical intervention to avoid multiple bowel resections and resection of the ileocecal valve, to prevent the development of short gut syndrome. Recent literature contends that when the Crohn’s disease is limited to the appendix, appendectomy alone is appropriate given minimal perioperative mortality and a 3.5% rate of fistula formation; nevertheless, this rate is increased to 15%-20% when the ileocecum is involved [5], [17].

It is uncertain if re-exploration with bowel resection could have been avoided in our patient if the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease had been known in prior to her initial surgery. We question whether underlying Crohn’s disease caused the patient’s appendicitis. While there was expected periappendiceal inflammation and multiple adhesions to surrounding structures, the typical histologic features of Crohn’s disease, such as transmural inflammation, epitheloid granulomas, lymphoid aggregates, and mucosal ulceration, were not present. Furthermore, given the patient’s short pre-operative clinical course, the presence of appendicoliths, and the likelihood of vascular compromise, we believe that her pathology was truly acute ruptured appendicitis. It is likely, however, that her Crohn’s was a major factor in the development of her non-healing colocutaneous fistulas. The delayed diagnosis of Crohn’s disease accounted for the chronic, uncontrolled inflammatory process within her hernia sac. Other factors may have predisposed the patient to fistula formation, including gross contamination from her ruptured appendix; while rare, subsequent fistula formation has been described in the literature [11]. Another factor is that the patient’s chronically incarcerated ventral hernia could have caused transient periods of ischemia, further compromising the integrity of the bowel.

4. Conclusion

This is the first report of incisional hernia appendicitis with nonhealing colocutaneous fistulas secondary to Crohn’s disease. We report this rare case presentation as lesson in developing a differential diagnosis for inflammatory process within an incarcerated hernia and management of complications associated with laparoscopic hernial appendectomy in a patient with undiagnosed Crohn’s disease.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Sources of funding

No funding was received by any author for this case report.

Ethical approval

Our institution’s Internal Review Board does not require approval for case reports or case series less than 3 patients.

Consent

The patient has given written consent for presentation and publication of her case without the inclusi

on of any identifying information.

Authors contribution

Erica Kane: direct involvement with the patient’s care, paper conception, manuscript draft, critical editing, and final approval of manuscript.

Katharine Bittner: Paper conception, manuscript draft, critical editing, and final approval of manuscript.

Michelle Bennett: Direct involvement with the patient’s care, manuscript draft, critical editing, and final approval of manuscript.

John Romanelli: Direct involvement with the patient’s care, critical editing, and final approval of manuscript.

Neal Seymour: Direct involvement with the patient’s care, critical editing, and final approval of manuscript.

Jacqueline Wu: Direct involvement with the patient’s care, paper conception, critical editing, and final approval of manuscript.

Guarantor

Erica Kane, MD, MPH.

Footnotes

Presented at: Americas Hernia Society 18th Annual Hernia Repair Meeting, March 8–11, 2017.

Contributor Information

Erica D. Kane, Email: erica.kanemd@baystatehealth.org.

Katharine R. Bittner, Email: kbitter@gmail.com.

Michelle Bennett, Email: michelle.bennett@tufts.edu.

John R. Romanelli, Email: john.romanelli@baystatehealth.org.

Neal E. Seymour, Email: neal.seymour@baystateshealth.org.

Jacqueline J. Wu, Email: jacqueline.wuMD@baystatehealth.org.

References

- 1.Sugrue C., Hogan A., Robertson I., Mahmood A., Khan W.H., Barry K. Incisional hernia appendicitis: a report of two unique cases and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2013;4(3):256–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machado N.O., Chopra P.J., Hamdani A.A. Crohn’s disease of the appendix with enterocutaneous fistula post-appendicectomy: an approach to management. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2010;2(3):158–161. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr J.A., Karmy-Jones R. Spigelian hernia with Crohn’s appendicitis. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. 1998;8(October (5)):398–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nauta R.J., Heres E.K., Walsh D.B. Crohn’s appendicitis in an incarcerated spigelian hernia. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1986;29(10):659–661. doi: 10.1007/BF02560332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meinke A.K. Review article: appendicitis In groin hernias. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2007;11:1368–1372. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singal R., Mittal A., Gupta A., Gupta S., Sahu P., Sekhon M.S. An incarcerated appendix: report of three cases and a review of the literature. Hernia. 2012;16:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0715-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Ramli W., Khodear Y., Aremu M., El-Sayed A.B. A complicated case of amyand’s hernia involving a perforated appendix and its management using minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery: a case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2016;29:215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajaguru K., Tan Ee Lee D. Amyand’s hernia with appendicitis masquerading as Fournier’s gangrene: a case report and review of the literature. J. Med. Case Rep. 2016;10:263. doi: 10.1186/s13256-016-1046-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han H., Kim H., Rehman A., Jang S.M., Paik S.S. Appendiceal Crohn’s disease clinically presenting as acute appendicitis. World J. Clin. Cases. 2014;2(12):888–892. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i12.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flood L., Chang K.H., McAnena O.J. A rare case of Amyand’s hernia presenting as an enterocutaneous fistula. JSCR. 2010;7:6. doi: 10.1093/jscr/2010.7.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Vanek V.W., Spirtos G., Awad M., Badjatia N., Bernat D. Isolated Crohn’s disease of the appendix: two case reports and a review of the literature. Arch. Surg. 1988;123:85–87. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400250095017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harnoss J.C., Zelienka I., Probst P., Grummich K., Müller-Lantzsch C., Harnoss J.M., Ulrich A., Büchler M.W., Diener M.K. Antibiotics versus surgical therapy for uncomplicated appendicitis: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials (PROSPERO 2015: CRD42015016882) Ann. Surg. 2017;265(May (5)):889–900. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atema J.J., van Rossem C.C., Leeuwenburgh M.M., Stoker J., Boermeester M.A. Scoring system to distinguish uncomplicated from complicated acute appendicitis. Br. J. Surg. 2015;102(July (8)):979–990. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Podda M.A., Cillara N.B., Di Saverio S.C., Lai A.A., Feroci F.D., Luridiana G.E., Agresta F.F., Vettoretto N.G., ACOI (Italian Society of Hospital Surgeons) Study Group on Acute Appendicitis Antibiotics-first strategy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis in adults is associated with increased rates of peritonitis at surgery. A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing appendectomy and non-operative management with antibiotics. Surgeon. 2017:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2017.02.001. Epub ahead of press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakran J.V., Mylonas K.S., Gryparis A., Stawicki S.P., Burns C.J., Matar M.M., Economopoulos K.P. Operation versus antibiotics–the appendicitis conundrum continues: a meta-analysis. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(6):1129–1137. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bischoff A., Gupta A., D’Mello S., Mezoff A., Podberesky D., Barnett S., Keswani S., Fischer J.S. Crohn’s disease limited to the appendix: a case report in a pediatric patient. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2010;26(11):1125–1128. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2689-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prieto-Nieto I., Perez-Robledo J.P., Hardisson D., Rodriguez-Montes J.A., Larrauri-Martinez J., Garcia-Sancho-Martin L. Crohn’s disease limited to the appendix. Am. J. Surg. 2001;182(November (5)):531–533. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00811-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudley T., Dean P. Idiopathic granulomatous appendicitis: or Crohn’s disease of the appendix revisited. Hum. Pathol. 1993;24(6):595–601. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90238-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weston L.A., Roberts P.L., Schoetz D.J. Ileocolic resection for acute presentation of Crohn’s disease of the ileum. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1996;39:841–846. doi: 10.1007/BF02053980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]