Abstract

Human skeletal progenitors were engineered to stably express R201C mutated, constitutively active Gsα using lentiviral vectors. Long‐term transduced skeletal progenitors were characterized by an enhanced production of cAMP, indicating the transfer of the fundamental cellular phenotype caused by activating mutations of Gsα. Like skeletal progenitors isolated from natural fibrous dysplasia (FD) lesions, transduced cells could generate bone but not adipocytes or the hematopoietic microenvironment on in vivo transplantation. In vitro osteogenic differentiation was noted for the lack of mineral deposition, a blunted upregulation of osteocalcin, and enhanced upregulation of other osteogenic markers such as alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and bone sialoprotein (BSP) compared with controls. A very potent upregulation of RANKL expression was observed, which correlates with the pronounced osteoclastogenesis observed in FD lesions in vivo. Stable transduction resulted in a marked upregulation of selected phosphodiesterase (PDE) isoform mRNAs and a prominent increase in total PDE activity. This predicts an adaptive response in skeletal progenitors transduced with constitutively active, mutated Gsα. Indeed, like measurable cAMP levels, the differentiative responses of transduced skeletal progenitors were profoundly affected by inhibition of PDEs or lack thereof. Finally, using lentiviral vectors encoding short hairpin (sh) RNA interfering sequences, we demonstrated that selective silencing of the mutated allele is both feasible and effective in reverting the aberrant cAMP production brought about by the constitutively active Gsα and some of its effects on in vitro differentiation of skeletal progenitors. © 2010 American Society for Bone and Mineral Research

Keywords: fibrous dysplasia, stromal cells, lentiviral vectors, skeletal progenitors

Introduction

Fibrous dysplasia (FD, OMIM 174800) is a noninherited disease of bone caused by activating missense mutations in the GNAS gene, which encodes the α subunit of the stimulatory G protein (Gsα).1, 2 Replacement of arginine 201 by either cysteine (R201C) or histidine (R201H) leads to expression of a constitutively active form of the Gsα protein, which, in turn, results in increased production of cAMP.3, 4, 5 The causative mutations are thought to occur postzygotically, resulting in a somatic mosaic state.6 Mutated cells derived from the originally mutated embryonic progenitor distribute to different organs, causing distinct patterns of organ disease.6 Of all the organ lesions, bone lesions appear to be the most severe and the least treatable. Complex histologic changes characterize FD bone,6, 7, 8 including the replacement of normal bone and bone marrow by abnormal, undermineralized, and mechanically unsound bone and fibrotic, nonhematopoietic bone marrow.7, 8

The origin of such changes from the dysfunction of mutated cells of the osteogenic lineage7, 9 suggested that FD can be seen as a disease of skeletal progenitors found in the postnatal bone marrow and of their abnormal, differentiated progeny.9 Indeed, mutated clonogenic progenitors can be isolated from the abnormal fibrotic bone marrow of FD lesions, and cell populations containing a mixture of normal and mutated clonogenic cells can be used to reproduce a miniature version of FD lesions on heterotopic transplantation in the immunocompromised mouse.9 Likewise, the use of cultures of bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) derived from FD lesions has been instrumental in elucidating important aspects of FD biology with direct clinical relevance, such as, for example, production of the phosphate‐regulating factor fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF‐23) by FD osteogenic cells.10 Skeletal progenitors thus have emerged as an essential tool for unraveling specific facets of the cellular effects of Gsα mutations in bone.

To date, there is no cure for FD. Medical treatment is palliative, and surgery, albeit essential to correct deformity and fracture, often fails when involvement of the individual bones is extensive.6 Design of more effective ways of pharmacologic intervention thus relies on the precise dissection of molecular derangements downstream of the mutation in critically important cell types. Hence a more thorough understanding of the effects of the mutation on skeletal progenitors is needed. This requires the availability of large numbers of skeletal progenitors, which is inherently limited by the relative rarity of the disease, by the heterogeneity of lesions in different patients and at different ages,11 and by clinical considerations that may limit the harvest of lesional bone and bone marrow for establishing cell cultures.

While highly valuable for modeling specific features of the disease in vitro and in vivo, use of FD‐derived cell strains as direct models of the biology of mutated skeletal progenitor/stem cells proper has limitations. Owing to the actual natural history of lesions, including an accelerated rate of consumption of mutated progenitors compared with their normal cognates, cultures of BMSCs from FD lesions are heterogeneous in content of mutated and nonmutated progenitor/stem cells.11 A specific stromal subset enriched in stem/progenitor cells has been identified in the normal bone marrow stroma12 but has not been purified from FD tissue. Furthermore, expression of the key markers of such normal stromal progenitors, such as CD146/MCAM, is characteristically low in cell strains established in culture from FD lesions,12 in sharp contrast with normal BMSC cultures. Seeking the specific subset of progenitor/stem cells in cultures of FD stromal cells could involve using the same approach as in normal bone marrow, that is, isolating antigenically defined cell subsets.12 Alternatively, one could conceive of targeting the FD‐causing mutation to cell strains enriched in normal skeletal progenitors. This would allow researchers to (1) minimize the inherent variability of FD‐derived stromal strains, (2) create de novo mutated progenitors, thus reducing the confounding variables emanating from the natural history of lesions itself and from the lifelong history of the disease genotype within the osteogenic lineage in vivo, and (3) establish a better controlled system of mutated progenitors in which to seek molecular derangements downstream of the causative mutation.

Besides representing a key tool for modeling disease mechanisms, skeletal progenitors also can be seen as a key tool for treatment themselves, either through the design of cell‐replacement strategies (made feasible by the circumstance that normal, nonmutated skeletal progenitors are found in FD patients in unaffected bones or even in affected bones13) or through the design of strategies for gene correction in skeletal progenitors. Since the causative mutations are dominant and gain‐of‐function and the mutated gene is indispensable in all tissues, any attempt toward genetic correction must envision the selective silencing of the mutated allele only.14, 15, 16, 17 Keeping these considerations in mind, we explored the possibility of (1) stably transferring the disease genotype and phenotype to normal human skeletal progenitors as an approach to model the mutation effects and (2) silencing the mutated allele in skeletal progenitors. For both purposes, we chose to rely on advanced‐generation lentiviral (LV) vectors, which can be used to transduce human skeletal progenitors stably and efficiently.18 We report here that LV vectors encoding the R201C mutated Gsα effectively transfer and RNA‐interfering sequences expressed from LV vectors can efficiently silence the disease phenotype in human BMSCs.

Materials and Methods

Normal hBMSCs, FD hBMSCs, and cell lines

Wild‐type (WT) human bone marrow stromal cells (hBMSCs) were isolated as described previously19 from surgical trabecular bone specimens or bone marrow aspirates obtained with informed consent.20, 21 FD hBMSCs were isolated from iliac crest bone biopsies of FD patients under an institutional review board–approved protocol (NIH 98‐D‐0145). Fresh bone tissue samples were used for mutation analysis and to establish nonclonal FD hBMSC cultures, as described previously.9 Antigenic profiles of WT and FD hBMSCs in culture were characterized by fluorescence‐activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis as described previously.12 WT and FD hBMSCs were cultured in α modified minimum essential medium (α‐MEM), 2 mM l‐glutamine, 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 10−8 M dexamethasone, and 10−4 M l‐ascorbic acid. 293T (ATCC CRL‐11268) and HeLa (ATCC CCL‐2) cells were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen), 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin.

Lentiviral vectors

To generate LV‐GsαWT and LV‐GsαR201C vectors, the SalI/HindIII cassette was excised from the rat WT Gsα cDNA (ATCC 63315, GenBank M12673) or the R201C rat Gsα cDNA (ATCC 63317, GenBank M12673), respectively, and inserted into the PmeI/SmaI sites of the pWPXLd‐GFP LV transfer vector (provided by D Trono22). Both cassettes include a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope as a flag. To generate the control vector (LV‐ctr), the eGFP cassette was excised from the pWPXLd‐GFP plasmid by PmeI/SmaI digestion and self‐ligation. In addition, the SalI/HindIII rat GsαR201C fragment was inserted into the SmaI/SalI sites of the pCCL.CTE.eGFP.minhCMV.hPGK LV vector (provided by L Naldini23) under control of the PGK promoter to produce the LV‐GFP‐GsαR201C vector. RNA‐interfering LV vectors and the control vector were generated by inserting the relevant hairpin duplexes (Operon Biotechnologies, GmbH, Cologne, Germany; Table 1) into the ClaI/MluI sites of the LVTHM vector.22 Recombinant LVs were produced as described previously.18 To determine the LV‐vector integrated copy number, transduced BMSCs were collected 2 weeks after infection, and genomic DNA was extracted with the DNA‐Easy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). LV copy number was calculated by qPCR as described previously.18

Table 1.

LV Vectors for RNA Interference

| Vector | Nucleotides | shRNA | Gene ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| LV‐siGsα ex1‐human | 407–425 | cgcgtccccggcgcagcgtgaggccaacttcaagagagttggcctcacgctgcgcctttttggaaat | NM_000516 |

| LV‐siGsαR201C‐1 | 839–857 | cgcgtccccttcgctgctgtgtcctgacttcaagagagtcaggacacagcagcgaatttttggaaat | M12673 |

| LVsiGsαR201C‐2 | 838–856 | cgcgtcccccttcgctgctgtgtcctgattcaagagatcaggacacagcagcgaagtttttggaaat | M12673 |

| LV‐siGsαR201C‐3 | 835–853 | cgcgtccccctgcttcgctgctgtgtccttcaagagaggacacagcagcgaagcagtttttggaaat | M12673 |

| LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 | 845–863 | cgcgtccccgctgtgtcctgacctctggttcaagagaccagaggtcaggacacagctttttggaaat | M12673 |

| LV‐siCtr | — | cgcgtcccccaccgacgtcgactgttggttcaagagaccaacagtcgacgtcggtgtttttggaaat | — |

Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence

Cells were transduced with the LV vectors at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) ranging from 1 to 10.18 Two weeks after infection, cells were collected, and proteins were extracted and separated as described previously.18 Recombinant Gsα protein was revealed with the anti‐Gsα rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:5000 dilution; Upstate Biotechnologies, Lake Placid, NY, USA) or anti‐HA monoclonal antibody (1:1500 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and green fluorescent protein (GFP) was detected with an anti‐GFP monoclonal antibody (1:30,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For immunofluorescence experiments, hBMSCs were grown on tissue culture–treated glass slides (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and processed as described previously24 by incubation with 12CA5 mouse monoclonal antibody raised against the HA tag (3 µg/mL; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) or rabbit polyclonal anti‐Gsα (1:200 dilution; Upstate Biotechnologies).

In vivo transplantation and in vitro differentiation

The ability of GsαR201C‐transduced hBMSCs to produce heterotopic ossicles was assessed by using an in vivo transplantation assay, as described previously.9, 20 Animal procedures were approved by the relevant institutional committee. hBMSCs were transduced with LV‐GFP‐GsαR201C at an MOI of 1. One week after transduction, they were transplanted subcutaneously into 8‐ to 15‐week‐old female nih/nu/xid/bg mice (Harlan–Sprague Dawley). Transplants also were generated using hBMSCs isolated from FD lesional tissue. Transplants were harvested at 8 weeks and processed for histology.9 For in vitro differentiation, transduced and mock‐treated hBMSCs were cultured in adipogenic and osteogenic media and then stained with oil red O or Von Kossa stain, respectively.25 For adipogenesis, cells were cultured for 3 weeks in α‐MEM, 20% FBS, 0.5 mM 3‐isobutyl‐1‐methylxanthine (IBMX, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), 60 µM indomethacin, and 1 µM dexamethasone. For osteoblastic differentiation, cells were cultured for 4 weeks in DMEM, 10% FBS, 10 mM β‐glycerophosphate, and 50 µg/mL l‐ascorbic acid.

RT‐PCR and qPCR

Mock or infected hBMSCs were collected at 7, 15, and 21 days after infection, total RNA was isolated with TRIzol, DNase (Invitrogen) treated, and reverse transcribed using the SuperScriptIII First‐Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). PCR amplifications were performed using primer pairs listed in Table 2, with the following conditions: 94°C for 2 minutes, 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at the different temperatures as reported in Table 2 for 30 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute and 30 seconds, and 72°C for 3 minutes for 30 cycles. mRNA expression of phosphodiesterases (PDEs) or osteogenic and adipogenic markers (Table 3) were measured by qPCR using an Applied Biosystems PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System and normalized to the internal GAPDH expression. To obtain relative quantification with respect to the undifferentiated mock cells, cycle threshold values (C t) were exported directly into an EXCEL worksheet for analysis, and the data were calculated with the 2–ΔΔC t method.26

Table 2.

PCR Primers and Conditions

| Marker | Forward primer 5′ → 3′ | Reverse primer 5′ → 3′ | RefSeq ID | T annealing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUNX‐2 | GAGGGTACAAGTTCTATCTGAA | GGCTCACGTCGCTCATTTTG | NM_004348 | 59°C |

| BGLAP | GCCGTAGAGCGCCGATAGGC | ATGAGAGCCCTCACACTCCTC | NM_199173 | 49°C |

| BSP | ATTGAAAAC GAAAGCGAAG | ATCATAGCCATCGTAGCCTTGT | NM_004967 | 49°C |

| ALP | GAGACACTGAAATATGCCCTGG | CTCATTGGCCTTCACCCCACACAG | NM_000478 | 56°C |

| RANKL | CAGGCCTTTCAAGGAGCTGTGCA | AAGGAGGGGTTGGAGACCTCGATGC | NM_003701 | 60°C |

| OPG | CTGTACAGCAAAGTGGAAGACCGTG | GCAGCTTCAGGATCTGGTCACTGG | NM_002546 | 60°C |

| PPARγ | TCTCTCCGTAATGGAAGACC | GCATTATGAGACATCCCCAC | NM_005037 | 50°C |

| LPL | GTCCGTGGCTACCTGTCATT | TGGATCGAGGCCAGTAATTC | NM_000237 | 58°C |

| PLIN | GTGCAATGCCTATGAGAAGGGCGTG | TACTCCACCACCTTCTCAATGCTGC | NM_002666 | 60°C |

| β‐Actin | CCGACAGGATGCAGAAGGAG | GGCACGAAGGCTCATCATTC | NM_001101 | 60°C |

Table 3.

Osteogenic Markers, Adipogenic Markers, and PDEs

| Gene name | Gene symbol | Assay ID |

|---|---|---|

| BGLAP | hCG1999357 | Hs01587813_g1 |

| IBSP | hCG38540 | Hs00173720_m1 |

| RUNX2 | hCG18129 | Hs00231692_m1 |

| ALP | hCG38868 | Hs00758162_m1 |

| RANKL | hCG32838 | Hs00243522_m1 |

| LPL | hCG22262 | Hs00172425_m1 |

| PLIN | hCG28639 | Hs00160173_m1 |

| PPARγ | hCG26772 | Hs00234592_m1 |

| GAPDH | hCG2005673 | Hs99999905_m1 |

| PDE3A | hCG22720 | Hs00168617_m1 |

| PDE3B | hCG23682 | Hs00265322_m1 |

| PDE4A | hCG28500 | Hs00183479_m1 |

| PDE4B | hCG1811271 | Hs00277080_m1 |

| PDE4C | hCG36766 | Hs00168632_m1 |

| PDE4D | hCG1811507 | Hs00174810_m1 |

| PDE7A | hCG40524 | Hs00300285_m1 |

| PDE7B | hCG33357 | Hs00184076_m1 |

| PDE10A | hCG34059 | Hs01098924_m1 |

| PDE11A | hCG2040017 | Hs00899218_m1 |

Cell proliferation

Untreated and LV‐transduced cells were cultured for 2 weeks and then plated in 6‐well plates. The cell number was recorded weekly for 21 days, and the proliferation was assessed as population doublings over time. For BrdU incorporation, cell samples were plated for 24 hours in 96‐well plates and then incubated with BrdU for 2 or 24 hours. Samples were processed as suggested in the manufacturer's instruction (BrdU Cell Proliferation Assay, Calbiochem, EMD Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany), and BrdU incorporation was quantified by spectrophotometry at 450 nm (Microplate Reader Model 550, Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

cAMP assay

Cells were cultured for 2 weeks and then plated in 48‐well plates at a density of 15,000 cells per well and incubated for 1 hour in serum‐free medium in the presence or absence of 1 mM IBMX (Sigma) or 1 mM IBMX and 10 µM forskolin (Calbiochem). cAMP was measured using the cAMP Direct Biotrak EIA kit (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions.27

Phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity

Cells were cultured for 7 days, rinsed with PBS, collected by scraping with PBS on ice, and lysed with a cold solution of HEPES 25 mM, 50 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X‐100, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, and 2 mM MgCl2 in the presence of the protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Germany). To measure intracellular PDE activity, 10 µL of total lysate was incubated with 10 µM cAMP (Sigma) as substrate for 20 minutes at room temperature in the presence or absence of IBMX (1 mM) or Rolipram (20 µM; Sigma) in PDE buffer (40 mM Tris‐HCl pH 8, 10 mM MgCl2, 1.25 mM 2‐mercaptoethanol, and 1% BSA). AMP was detected using the PDELight HTS cAMP Phosphodiesterase kit (Cambrex, Rockland, ME, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Bioluminescence was measured with a luminometer normalized for total protein and expressed as relative light units (RLUs).

Statistical analysis

All data were reported as mean ± SD. Multiple group comparisons were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test for pair‐wise comparison using Minitab13 software. A p value of less than .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Transfer of the disease genotype and phenotype to BMSCs by lentiviral transduction

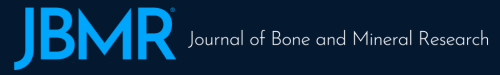

To stably transfer the R201C Gsα gene into skeletal progenitors cells, we constructed an LV vector expressing the mutated Gsα protein, controlled by the human EF1α promoter and detectable by means of the HA epitope (Fig. 1 A) and used it to transduce CD146/MCAM high/bright BMSCs isolated from normal bone marrow by plastic adherence at low density.12 High expression of additional markers of stromal progenitors (CD90, CD140b, CD63, CD105, CD49a, and ALP) in CD146+ BMSCs was confirmed by FACS analysis (not shown). As assessed by Western blot analysis and HA immunofluorescence (Fig. 1 B, C), transduction of BMSCs with LV‐GsαR201C or LV‐GFP‐GsαR201C resulted in highly efficient (∼90% at an MOI of 1) transgene expression, which remained stable for at least 90 days. Transduced cells retained high levels of expression of CD146/MCAM, a key marker of skeletal progenitors,12 as shown by Western blot and qPCR analysis (data not shown). The two splice variants of Gsα normally transcribed from the GNAS gene in human cells (48 and 43kDa, Gsα‐long and Gsα‐short, respectively) were found to be expressed at similar levels in untransduced BMSCs (Fig. 1 B). Consistent with the nature of the Gsα constructs used for vector generation, which excludes alternative splicing, only Gsα‐long was induced by LV‐GsαR201C transduction, as detected by the HA antibody (Fig. 1 B). Since the R201C mutation conveys a constitutive activity to the mutated Gsα that is thought to result in increased concentrations of cAMP, cAMP concentration was measured in LV‐GsαR201C‐BMSCs in comparison with mock‐treated and empty vector–infected cells. In the absence of the PDE inhibitor IBMX, no difference in cAMP concentration could be detected in transduced cells compared with controls (Fig. 1 D). However, in the presence of IBMX alone or of both IBMX and the adenylyl cyclase agonist forskolin, cAMP concentration was significantly higher in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells than in control cells. Hence higher levels of cAMP compared with controls could be observed only on inhibition of PDE activity.

Figure 1.

Lentiviral transfer of GsαR201C mutation in hBMSCs. (A) LV vectors used for GsαR201C transfer. LV‐EF‐GsαR201C encodes the GsαR201C protein (HA‐tagged), controlled by the EF‐1α promoter. The bidirectional LV vector (LV‐BD‐GsαR201C) encodes GsαR201C and eGFP under the control of the PGK and CMV minimal promoters, respectively. (B) Western blot analysis of GsαR201C expression in LV‐EF‐GsαR201C‐transduced hBMSCs. Immunoblotting for HA demonstrates the specific signal for the mutated Gsα protein. Immunoblotting for Gsα demonstrates that mock‐treated and empty vector (LV‐Ctr)–transduced cells express comparable amounts of the 48‐ and 43‐kDa isoforms of Gsα (Gsα‐long and Gsα‐short, respectively) resulting from alternative splicing of exon 3. A specific increase of Gsα‐long is observed in cells transduced with LV‐EF‐GsαR201C. (C) GsαR201C expression in hBMSCs is detected by immunofluorescence, as indicated by HA immunolabeling. (D) Intracellular cAMP levels were measured in control or LV‐EF‐GsαR201C‐transduced hBMSCs. In the presence of IBMX (1 mM) alone or of IBMX and forskolin (10 µM), significantly higher levels of cAMP are observed in GsαR201C‐expressing cells compared with control cells. Data from five separate experiments in duplicate are expressed as mean ± SD. a p < .05 versus mock and LV‐ctr; b p < .01 versus mock and ctr.

Effects of LV‐GsαR201C transduction on proliferation and differentiation of skeletal progenitors

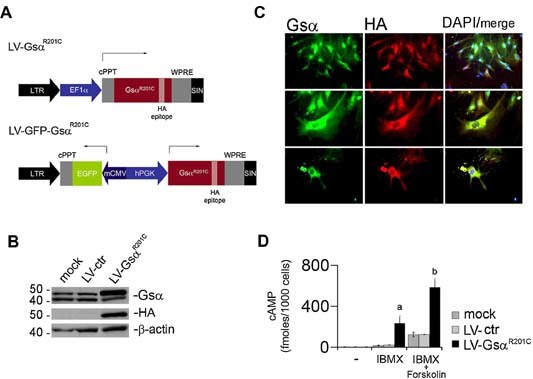

Proliferation of transduced cells was measured both as the number of population doublings over time and by BrdU incorporation (Fig. 2 A, B). In both types of experiments, LV‐GsαR201C transduction had no detectable effect on BMSC proliferation in vitro. The ability of LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced skeletal progenitors to differentiate into osteoblasts and adipocytes was assayed in vivo and in vitro. Normal, FD‐derived, and LV‐GNASR201C‐transduced strains of stromal cells were expanded in culture and transplanted subcutaneously into immunocompromised mice as per established protocols (Fig. 2 C). Whereas control cells generated complete ossicles including bone and hematopoietic tissue and marrow adipocytes, LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells formed defective heterotopic ossicles comprised of woven bone and fibrous tissue but lacking hematopoietic tissue and adipocytes. Transplants generated by FD BMSCs were virtually identical, indicating that LV‐ GNASR201C‐transduced skeletal progenitors behaved in this assay in a manner similar to FD‐derived cells (Fig. 2 C).

Figure 2.

Effect of GsαR201C on hBMSC proliferation and in vivo differentiation. Analysis of cell proliferation in transduced hBMSCs expressed as (A) population doublings or (B) BrdU incorporation for 2 and 24 hours. The presence of mutated GsαR201C does not alter BMSC proliferation. Data from three experiments are expressed as means ± SD. (C) In vivo transplantation of normal, FD‐derived (R201C) and LV‐ GsαR201C‐transduced hBMSCs. Note the formation of abundant bone (b) on hydroxyapatite (ha/tcp, hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate), hematopoietic tissue (hem, meg = megakaryocytes), and adipocytes (ad) in control transplants (upper panels). Transplants of FD‐derived BMSCs and transduced BMSCs are recognized by the reduced amount of bone and the fibrous tissue (ft) devoid of hematopoietic cells and adipocytes filling the marrow space. Polarized light microscopy demonstrates that normal BMSCs formed lamellar bone (lb), whereas transduced BMSCs formed woven bone (wb).

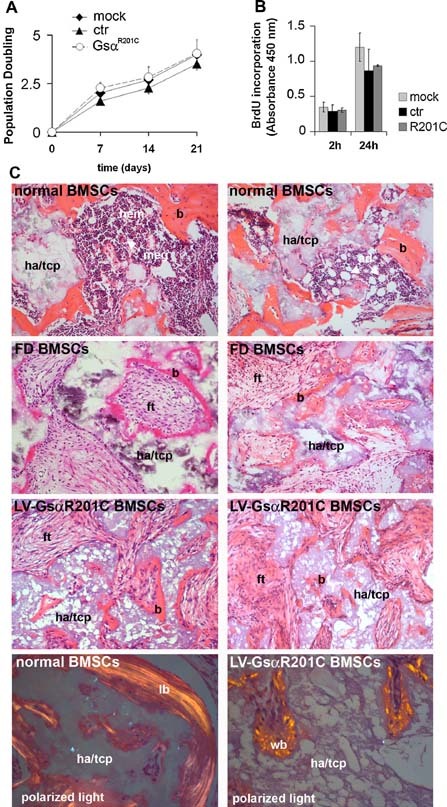

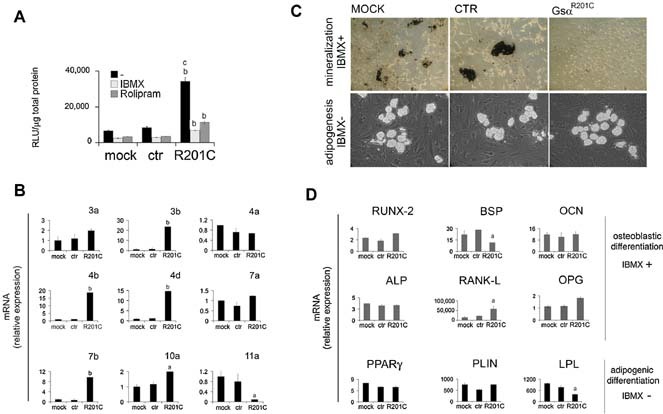

RT‐PCR analysis of osteogenic markers in undifferentiated cells revealed the strong induction of RANKL mRNA in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells compared with mock‐ and control‐transduced cells (Fig. 3 A). When control cells were exposed to osteogenic medium in vitro, induction of mineralization (Fig. 3 B) was associated with a modest increase in expression of Runx2 (∼2‐fold) and BSP (∼3‐fold) and a robust increase in OCN mRNA (∼10‐fold) as assessed by qPCR compared with nondifferentiated cells (Fig. 3 C). In LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells, matrix mineralization was reduced dramatically (Fig. 3 B). However, a significantly more pronounced increase in expression of ALP (∼5‐fold) and BSP (∼20‐fold) compared with control cultures and a striking upregulation of RANKL mRNA (∼15,000‐fold) were observed. In contrast, the increase in OCN mRNA expression in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells over nondifferentiated cells was only about a third of the increase observed in control (mock‐ and LV‐ctr‐transduced) cells (Fig. 3 C).

Figure 3.

GsαR201C effect on the adipogenic and osteogenic markers in undifferentiated and in vitro differentiated hBMSCs. (A) Adipogenic and osteogenic marker quantification in GsαR201C‐transduced hBMSCs. RT‐PCR analysis was carried out in undifferentiated uninfected and LV‐ctr‐ or LV‐GsαR201C‐infected hBMSCs. Significant activation of RANKL is detected in LV‐GsαR201C‐infected hBMSCs. (B) Adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of GsαR201C‐transduced hBMSCs. hBMSCs were cultured in osteogenic and adipogenic medium, and mineralization nodules or adipocyte‐like cells were revealed with Von Kossa and oil red O staining, respectively. Both in vitro osteogenic differentiation and in vitro adipogenic differentiation of hBMSC are altered in GsαR201C‐transduced cells. (C) qPCR of osteogenic and adipogenic markers analyzed in differentiated hBMSCs. Abnormal differentiation was observed in GsαR201C‐transduced cells compared with mock‐transduced and control cells. Data from four experiments in duplicates are expressed as means ± SD. a p < .05 versus mock and ctr; b p < .01 versus mock and ctr.

RT‐PCR analysis of adipogenic markers in undifferentiated cells revealed the induction of at least one adipogenic marker (PLIN) mRNA in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells compared with mock‐ and control‐transduced cells (Fig. 3 A). In control cells exposed to adipogenic conditions, development of lipid‐containing, adipocyte‐like cells (Fig. 3 B) was associated with marked increase in mRNA levels for PPARγ (20‐ to 30‐fold), PLIN (∼5,000‐fold), and LPL (∼5,000‐fold) over nondifferentiated cells. Significantly lower increases of the same markers were observed in cells transduced with mutated Gsα (Fig. 3 C), which did not generate adipocyte‐like cells (Fig. 3 B).

Adaptive enhancement of PDE activity and mRNA levels in Gsα‐transduced BMSCs

Since a marked change in cAMP concentration in transduced cells was strictly dependent on the inhibition of PDE activity by IBMX, we measured total PDE activity in extracts of transduced and control cells. In the absence of PDE inhibitors, total PDE activity in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells was approximately fourfold higher than in control cells (Fig. 4 A). In the presence of IBMX, PDE activity was still significantly higher in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells than in control cells. Rolipram, a specific inhibitor of one of the principal cAMP‐degrading PDEs, PDE4, partially reduced the PDE activity in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells. This suggested that while PDE4 was involved in the increased PDE activity of transduced cells, other PDE isoforms also could be involved. Analysis of expression of the mRNAs of different cAMP‐degrading PDEs by qPCR revealed that the enhanced PDE activity of transduced cells was coupled with increased expression of selective PDE isoforms. PDE3b, ‐4b, ‐4d, ‐7b, and ‐10a were expressed at significantly higher levels in cells transduced with LV‐GsαR201C compared with control cells (Fig. 4 B). PDE4a and ‐7a were expressed at similar levels in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced and control cells, whereas PDE11a was downregulated in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells. We concluded that an enhanced PDE activity and a selective increase in the expression of specific PDE isoforms are associated with transduction of BMSCs with mutated Gsα. This predicts an adaptive response that might be effective in limiting the rise in measurable cAMP concentration in the presence of constitutively active, mutated Gsα in PDE‐sufficient cells.

Figure 4.

Activity, mRNA expression, and phenotypic effects of PDEs in mutation‐transduced hBMSCs. (A) PDE activity was assayed in hBMSCs, mock‐treated or transduced with LV‐Ctr or LV‐ EF‐GsαR201C, using 10 µM of cAMP as a substrate, in the presence or absence of either IBMX (1 mM) or Rolipram (20 µM). b p < .01 versus equally treated mock and ctr cells; c p < .01 versus mutation‐transduced, IBMX‐ and rolipram‐treated cells. (B) qPCR analysis of the expression of PDE isoforms involved in cAMP degradation. Significant increase of expression was detected for PDE‐3b, ‐4b, ‐4d, and ‐7b isoforms in mutation‐transduced cells compared with mock‐ and LV‐Ctr‐treated cells. Values represent the mean ± SD of three experiments in duplicate. a p < .05 versus mock and ctr; b p < .01 versus mock and ctr. (C) hBMSCs were cultured in osteogenic medium supplemented with IBMX (0.5 mM) or adipogenic medium without IBMX. Mineralization nodules or adipocyte‐like cells were revealed with Von Kossa and oil red O staining, respectively. (D) PDE inhibition in osteogenic medium caused a significant upregulation of osteogenic markers in mock‐transduced and control cells at the same levels of GsαR201C. Adipogenesis in the absence of IMBX leads to a modest increase of adipogenic markers to the same extent in control and GsαR201C cells. a p < .05 versus mock and ctr.

PDE activity influences the differentiation of LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced skeletal progenitors

To investigate the influence of PDE activity on LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cell differentiation, the osteogenic differentiation assays also were conducted in the presence of IBMX. Conversely, the adipogenic differentiation assays, which are routinely assayed in the presence of IBMX, also were conducted in the absence of IBMX. Matrix mineralization still occurred in control cells and not in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells in the presence of IBMX (Fig. 4 C). IBMX produced a markedly greater upregulation of ALP (4‐fold), RANKL (15,000‐20,000‐fold), and BSP (20‐ to 30‐fold) in control cells (Fig. 5 B). Notably, these responses mimicked to some extent the effect of LV‐GsαR201C transduction in the absence of IBMX. IBMX had no effect on upregulation of OCN (10‐fold) in control cells. In LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells, IBMX in the osteogenic medium had no effect on ALP, an even more pronounced stimulation of RANKL (60,000‐fold), a smaller upregulation of BSP, and a greater upregulation of OCN (10‐fold) compared with osteogenic medium devoid of IBMX (Fig. 4 D). We concluded that transduction with GsαR201C had effects on osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, some of which were directly dependent on expression of the mutated Gsα and independent of the levels of PDE activity. These included a stimulation of ALP, RANKL, and BSP expression and a relative inhibition of OCN mRNA upregulation compared with control cells. Addition of IBMX to the osteogenic medium resulted in a more effective upregulation of multiple osteogenic markers in control cells. In LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells, it further increased the dramatic upregulation of RANKL and OCN (Fig. 4 D).

Figure 5.

Specific and stable LV‐mediated silencing of GsαR201C in normal and FD hBMSCs. (A) Schematic representation of the LV vectors expressing the Gsα RNA‐interfering sequences under the control of the H1 promoter and eGFP as a marker. (B) Design of different RNA‐interfering sequences directed to human exon 1 and human/rat GsαR201C exon 8. (C) Left panel: HeLa cells were first infected with the bidirectional LV‐GFP‐GsαR201C and subsequently superinfected with the different LV‐siGsα vectors as indicated. Specific knockdown of mutated Gsα was obtained only with LV‐siGsαR201C‐4. Right panel: HeLa GFP‐GsαR201C/siCtr or HeLa GFP‐GsαR201C/siGsαR201C‐4 were superinfected with LV‐EF1α‐GsαR201C or LV‐EF1α‐GsαWT. A specific downregulation of the added‐in mutated R201C Gsα was observed. In contrast, robust expression of the added‐in GsαWT was observed. (D) Left panel: Highly mutated in R201C, FD‐derived hBMSCs were mock infected or treated with LV‐siCtr or LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 and after 20 days of culture, the cells were collected for Western blot analysis. A decrease in both the long and short endogenous form of Gsα was observed with LV‐siGsαR201C‐4. Right panel: Normal hBMSCs were untreated or treated with LV‐siCtr, LV‐siGsαR201C‐4, and LV‐siGsα human exon 1 (hu). The 20 days after infection, cells were processed for Western blotting. Both Gsα endogenous WT isoforms (long and short Gsα) were efficiently suppressed with siGsα exon 1 but remained efficiently expressed with specific siGsαR201C‐4. (E) cAMP assay on HeLa LV‐GFP‐GsαR201C/siGsαR201C‐4 demonstrates the capacity to restore the cAMP levels similar to that of the basal levels. Data are means ± SD of n = 3 experiments in duplicate. b p < .01 versus untransduced HeLa equally treated; c p < .01 versus LV‐GsαR201C and LV‐GsαR201C/LV‐siCtr cells equally treated. (F) cAMP assay on transduced FD‐derived BMSCs and normal hBMSCs. A significant reduction of cAMP levels, comparable with that recorded in normal hBMSC, was observed in FD‐LV‐siGsαR201C‐4. a p < .05 of FD‐LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 versus FD mock, FD‐LV‐siCtr, and hBMSC‐GsαR201C.

When mock‐transduced control and LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells were exposed to adipogenic medium in the absence of IBMX, formation of adipocyte‐like cells was observed in all cultures (Fig. 4 C), indicating that expression of a constitutively active Gsα per se does not block adipogenic differentiation of BMSCs. In the absence of IBMX, the magnitude of PPARγ, PLIN, and LPL upregulation (fold increase) was similar in control and LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells (Fig. 4D). In control cells, the magnitude of upregulation of adipogenic markers was smaller in the absence than in the presence of IBMX, indicating that inhibition of PDE activity enhanced adipogenesis in cells expressing wild‐type Gsα only. In LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells, in contrast, the upregulation of adipogenic markers was more pronounced in the absence than in the presence of IBMX, indicating that PDE inhibition had opposite effects in control and LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced BMSCs; that is, while it promoted adipogenesis in WT cells, it abrogated adipogenesis in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells.

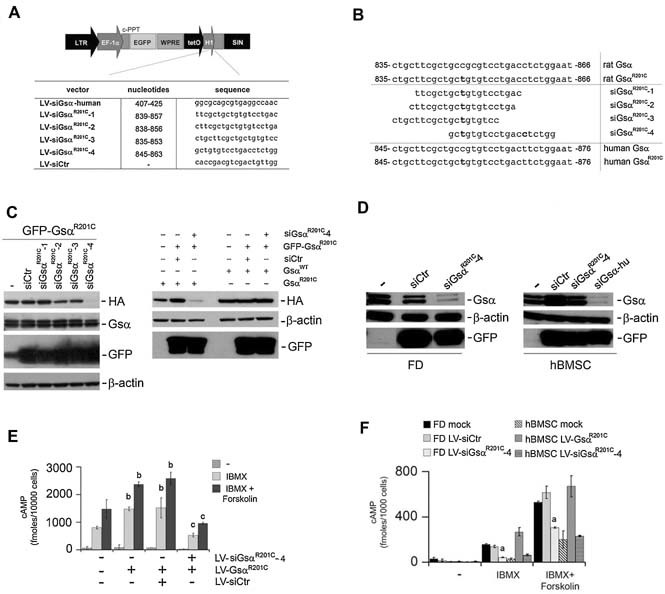

GsαR201C can be specifically silenced in skeletal progenitors

To investigate the possibility of specifically silencing the Gsα mutated allele, we constructed LV vectors encoding different shRNAs22 (Fig. 5 A). In order to obtain an optimal discrimination between the R201C mutated and wild‐type alleles, GsαR201C‐specific siRNAs sequences were designed by placing the mutation at position 9, 10, or 13, respectively (LV‐siGsαR201C‐1, LV‐siGsαR201C‐2, LV‐siGsαR201C‐3). An additional siRNA, LV‐siGsαR201C‐4, was designed in which the mutated nucleotide was placed in position 3 and an additional mismatch was inserted in position 14 (Fig. 5 B). This sequence matched perfectly the rat GsαR201C construct and differed from human GsαR201C or from wild‐type Gsα by one base and from human wild‐type Gsα by two bases.

To assess the activity and potential specificity of the different siRNAs, HeLa cells transduced with LV‐GFP‐GsαR201C were infected with LV‐siGsαR201C‐1 to ‐4, and the expression of mutated and wild‐type Gsα was analyzed by Western blot analysis. This revealed that siGsαR201C‐1 to ‐3 failed to inhibit the expression of either the mutated or the human wild‐type Gsα. In contrast, LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 resulted in a strong and selective silencing of the mutated rat Gsα transgene (Fig. 5 C). To confirm the specificity of LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 for mutated Gsα, HeLa cells in which expression of mutated Gsα from LV‐GFP‐GsαR201C was silenced successfully with LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 were further expanded in culture and superinfected with either LV‐EF1α‐GsαR201C or LV‐EF1α‐GsαWT. Superinfection with LV‐EF1α‐ GsαR201C did not restore significant expression of the HA‐containing mutated Gsα. In contrast, superinfection with LV‐EF1α‐GsαWT resulted in robust expression of HA‐tagged protein (Fig. 5 C).

Next, we asked whether the mutated Gsα allele also could be specifically knocked down in human FD‐derived BMSCs. Western blot analysis demonstrated that LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 significantly reduced the expression of Gsα in FD cells, which express the mutated allele, but not in normal BMSCs, which express only the wild‐type allele (Fig 5 D, left and right panels). In contrast, the wild‐type allele could be effectively knocked down with LV‐siGsα exon 1 (Fig. 5 D).

To determine whether specific silencing of mutated Gsα was functionally relevant, we measured the cAMP levels in cells that were transduced either with LV‐GsαR201C or with both LV‐GsαR201C and siGsαR201C‐4 (Fig. 5 E). In both HeLa cells and hBMSCs, levels of cAMP in the presence of IBMX/forskolin were significantly higher in LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced cells than in untransduced cells. Knockdown of GsαR201C restored normal levels of cAMP in both types of cells, whereas control siRNA sequences had no effect (Fig. 5 F). Likewise, in the presence of IBMX, levels of cAMP, which were significantly higher in mock‐treated FD cells than in mock‐treated BMSCs, were restored to normal levels in FD cells on knockdown of mutated Gsα (Fig. 5 F).

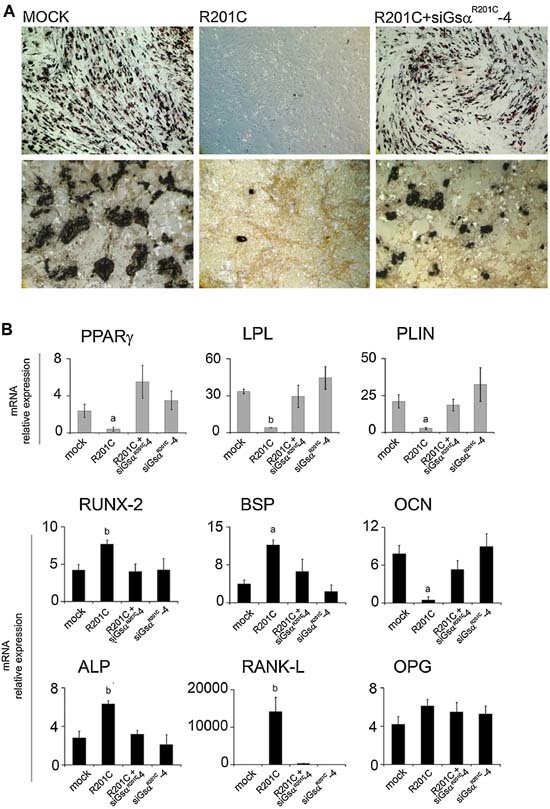

We then asked whether restoration of a normal‐rate production of cAMP would translate into any reversion of the abnormal differentiation induced by GsαR201C. LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced BMSCs were superinfected with LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 and induced to osteogenic or adipogenic in vitro differentiation. In cultures of LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced BMSCs, specific knockdown of GsαR201C restored the formation of adipocyte‐like cells and mineralization nodules (Fig. 6 A). Expression of osteogenic and adipogenic marker mRNAs also was restored to levels comparable with those seen in mock‐treated cells (Fig. 6 B). Conversely, transduction of wild‐type BMSCs with LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 only did not affect marker expression.

Figure 6.

Specific lentivirus‐directed RNA interference of constitutively active Gsα restores in vitro differentiation of LV‐GsαR201C‐transduced skeletal progenitors. (A) Restoration of in vitro adipogenesis (top, oil red O) and mineralization (bottom, von Kossa staining) in BMSCs that were first transduced with LV‐GsαR201C and then superinfected with LV‐siGsαR201C‐4. (B) Restoration of expression of mRNAs for adipogenic and osteogenic marker, qPCR analysis. Knockdown of mutated Gsα by LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 in previously GsαR201C‐transduced cells reestablishes the markers expression at the same levels as seen in mock cells. siGsαR201C‐4 does not affect the differentiation of untransduced cells. Data from four experiments in duplicate are expressed as means ± SD. a p < .05 versus mock, LV‐GsαR201C plus LV‐siGsαR201C‐4, and LV‐siGsαR201C‐4; b p < 0.01 versus mock, LV‐GsαR201C plus LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 and LV‐siGsαR201C‐4. No significant difference in expression levels occurs among mock and LV‐GsαR201C plus LV‐siGsαR201C‐4, mock, and LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 or LV‐GsαR201C plus LV‐siGsαR201C‐4 and LV‐siGsαR201C‐4.

Discussion

To date, studies on skeletal progenitors in FD have employed only cell strains derived in culture from FD tissue. While invaluable in unraveling specific features of the disease biology at the tissue level, the use of stromal cell strains directly explanted from FD lesions has obvious drawbacks. Frequency of mutated progenitors, cellular composition, and biologic properties of FD stromal cell strains necessarily reflect a lifelong in vivo history of the disease genotype within the osteoblastic lineage and a marked degree of clinical variability that may hamper the efficient and precise dissection of molecular mechanisms downstream of the mutation. Long‐term transduction of postnatal skeletal progenitors with functional, mutated Gsα circumvents many of the sources of unwanted variability associated with the use of FD‐derived stromal cell strains. In normal bone marrow, isolation of clonogenic stromal cells by adherence at low density or by immune selection using key markers such as CD146/MCAM does provide a way to enrich for self‐renewing progenitor/stem cells.12 The possibility to stably transduce these cells with the FD‐causing mutation(s), as in this study, provides a novel tool that complements culturing FD‐derived cells. FD‐derived cells reflect the effects of activating GNAS mutations on the osteoblastic lineage over years. These effects include important changes in composition and properties of the stromal population and in the frequency and viability of mutated progenitors themselves. Mutation‐transduced stromal strains, in contrast, portray the effects of de novo introduced, FD‐causing mutations on a cell population enriched in skeletal progenitors.

In this study, we used LV vectors to generate transgenic human skeletal progenitors expressing the R201C mutated Gsα protein. We have shown that permanent transfer of the mutated Gsα cDNA in skeletal progenitors results in the transfer of the fundamental cellular phenotype linked to a constitutively active Gsα, that is, an increased production of cAMP.

We also have shown here that nonclonal strains of BMSCs, highly enriched (∼90%) in mutation‐transduced skeletal progenitors, behave in a similar way as nonclonal strains of FD‐derived cells when transplanted in vivo, which include variable proportions of mutated and wild‐type cells.9, 20 Whereas their ability to generate histology‐proven bone tissue is not abrogated, nonclonal mutation‐transduced skeletal progenitors do not display the ability of normal BMSCs to transfer the hematopoietic microenvironment or to give rise to marrow adipocytes in vivo. As a result, the histology of heterotopic ossicles generated by mutation‐transduced cells mirrors in some respects the histology of natural FD lesions, in which a fibrotic bone marrow stroma, lacking adipocytes, fails to accommodate hematopoiesis. Taken together, in vivo data obtained in this and previous studies suggest that natural or forced expression of a constitutively active Gsα in stromal progenitors impairs adipogenesis while not preventing osteogenic differentiation, although abnormal bone is formed.

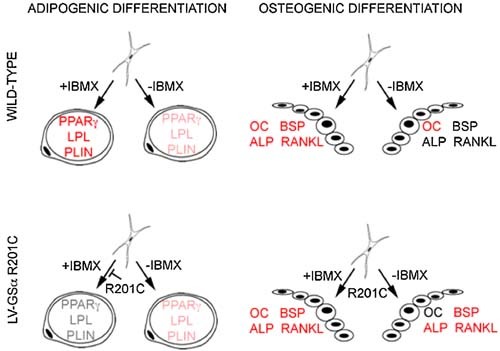

cAMP signaling has complex effects on adipogenesis. cAMP and cAMP‐dependent CREB activation are required for adipogenesis.28, 29, 30 On the other hand, Gsα activity is known to inhibit adipogenesis.31, 32 Adipogenic markers were modestly but detectably upregulated in LV‐GNASR201C‐transduced cells that were not exposed to either IBMX alone or adipogenic medium. These cells could generate adipocyte‐like cells and further upregulate adipogenic markers if exposed to an adipogenic medium not containing IBMX. However, both the upregulation of adipogenic markers and the generation of adipocyte‐like cells were completely blocked in transduced cells exposed to an adipogenic medium containing IBMX. PDE inhibition by IBMX promoted adipogenesis in wild‐type cells but blocked adipogenesis in transduced cells. Conceivably, constitutive activity of Gsα in PDE‐sufficient cells and regulated activity of Gsα in PDE‐inhibited cells both enhance adipogenesis in BMSCs through limited increases in cAMP and activation of the relevant CREB‐dependent pathways. Conversely, the much more pronounced surges in cAMP concentrations that are recorded on PDE inhibition in the presence of constitutively active Gsα markedly inhibit adipogenesis (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the interplay of Gsα and PDE activity in the regulation of in vitro adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. Inhibition of PDE (IBMX) results in marked enhancement of upregulation of adipogenic markers in BMSCs induced to in vitro adipogenesis. Constitutive activity of Gsα (R201C) results in a less prominent but clear‐cut enhanced expression of adipogenic markers. Inhibition of PDE in the presence of constitutively active Gsα, in contrast, results in the block of adipogenic differentiation. In BMSCs induced to in vitro osteogenic differentiation, addition of IBMX enhances the upregulation of BSP, ALP, and RANKL. Enhanced expression of the same markers is also observed in the absence of IBMX as an effect of constitutive activity of Gsα. Magnitude of enhancement is represented schematically by red, light red, and gray character colors in the notation of the different markers.

We also have shown that the upregulation of genes characteristic of osteogenic differentiation, which is triggered by the exposure of BMSCs to dexamethasone and ascorbic acid in culture, is significantly altered in mutation‐transduced cells. Upregulation of ALP and BSP mRNAs was much more prominent in transduced cells than in control cells. Conversely, upregulation of osteocalcin and deposition of a mineral phase were inhibited in mutation‐transduced BMSCs relative to control cells. Since mutated cells retained the ability to form bone in vivo, these data suggest that rather than an impairment in osteogenic differentiation, Gsα mutations lead to an altered coordination of this process. Interestingly, we observed a dramatic upregulation of RANKL. This predicts a significantly enhanced capacity of mutated osteogenic cells to promote osteoclastogenesis, a known phenomenon in FD tissue and an important determinant of the pathology of FD lesions. Notably, ALP, BSP, and RANKL all contain cAMP response elements in their promoters. Overall, the changes observed in mutation‐transduced skeletal progenitors induced to osteoblastic differentiation in vitro seem consistent with changes observed in natural FD bone, such as an impaired mineralization33 and an enhanced osteoclastogenesis,34 or in FD‐derived cells in culture, in which, for example, reduced osteocalcin35 and enhanced ALP expression36 were observed.

The notion of an increased and sustained cAMP production as a direct downstream effect of Gsα‐activating mutations has been established through repeated observations made in a variety of cell types and experimental systems.6, 37, 38, 39 Although commonly assumed, steady‐state increased concentration of cAMP in Gsα‐mutated cells is not necessarily implied by the constitutive activity of mutated Gsα. We have shown that BMSCs respond to stable transduction with a mutated Gsα by selectively upregulating specific PDE isoforms. As a result, markedly higher levels of cAMP in transduced versus control cells become only detectable on PDE inhibition with IBMX, as is commonly used in assays measuring the levels of cAMP. Our data indicate that overactivity of adenylyl cyclase induced by the expression of a constitutively active Gsα is in fact counteracted in human bone marrow stromal cells by an adaptive cellular response (upregulation of specific PDE isoforms), which would tend to minimize the effects on the actual cAMP intracellular concentration. Whereas such an adaptive response has been suggested previously to occur in other cell types,39, 40, 41, 42, 43 it had not been shown to occur either in the context of FD or in cells of osteogenic lineage, which are implicated in the development of FD lesions in bone. When extrapolated to the pathophysiology of osteogenic cells carrying the FD causative mutations, such an adaptive response and its potential failure over time could contribute to elucidation of certain hitherto unexplained features of the natural history of the disease, for example, the fact that Gsα‐activating mutations are compatible with normal bone formation during development and only result in an FD lesion in postnatal life.

Transfer of the causative gene of FD in human skeletal progenitors can provide not only an important tool for investigating disease mechanisms but also a model system for investigating innovative therapeutic interventions. Dissection of disease mechanisms downstream of the causative mutation per se could provide novel angles on the design of effective drugs. In addition, strategies for genetic correction of skeletal progenitors become feasible. The dominant gain‐of‐function nature of the FD‐causing mutation, the ubiquitous expression of Gsα, and its indispensable function in multiple tissues impose that attempt toward gene therapy of FD in skeletal progenitors be conceived of as the selective silencing of the mutated allele. To this end, we exploited the high efficiency and stability of lentiviral transduction in skeletal progenitors to introduce RNA‐interfering sequences that would be specific for the mutated allele. We have shown that selective silencing of mutated Gsα can in fact be achieved, leaving expression of the wild‐type protein unscathed. Furthermore, we have shown that the inappropriate production of cAMP brought about by constitutive activity of Gsα can in fact be reverted using LV‐mediated RNA interference. Likewise, the aberrant in vitro differentiation of mutation‐transduced skeletal progenitors also can be fully reverted by lentiviral knockdown of the mutated Gsα. These data provide the first evidence for the feasibility of a gene therapy approach based on selective knockdown, in skeletal progenitors, of the dominant gain‐of‐function Gsα mutations that cause FD.

Disclosures

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The financial support of Telethon Italy (Grant GGP09227) and Fondazione Roma is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1. Weinstein LS, Shenker A, Gejman PV, Merino MJ, Friedman E, Spiegel AM. Activating mutations of the stimulatory G protein in the McCune‐Albright syndrome. N Engl J Med 1991; 325: 1688–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shenker A, Weinstein LS, Moran A, et al. Severe endocrine and nonendocrine manifestations of the McCune‐Albright syndrome associated with activating mutations of stimulatory G protein GS. J Pediatr 1993; 123: 509–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Masters SB, Miller RT, Chi MH, et al. Mutations in the GTP‐binding site of GSα alter stimulation of adenylyl cyclase. J Biol Chem 1989; 264: 15467–15474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levis MJ, Bourne HR. Activation of the α subunit of Gs in intact cells alters its abundance, rate of degradation, and membrane avidity. J Cell Biol 1992; 119: 1297–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bourne HR, Landis CA, Masters SB. Hydrolysis of GTP by the α‐chain of Gs and other GTP‐binding proteins. Proteins 1989; 6: 222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bianco P, Robey PG, Weintroub S. Fibrous dysplasia In: Glorieux FH, Pettifor JM, Juppner H, eds. Pediatric Bone. San Diego: Academic Press; 2003: 509–539. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Riminucci M, Fisher LW, Shenker A, Spiegel AM, Bianco P, Gehron Robey P. Fibrous dysplasia of bone in the McCune‐Albright syndrome: abnormalities in bone formation. Am J Pathol 1997; 151: 1587–1600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Riminucci M, Liu B, Corsi A, et al. The histopathology of fibrous dysplasia of bone in patients with activating mutations of the Gsα gene: site‐specific patterns and recurrent histological hallmarks. J Pathol 1999; 187: 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bianco P, Kuznetsov S, Riminucci M, Fisher LW, Spiegel AM, Gehron Robey P. Reproduction of human fibrous dysplasia of bone in immunocompromised mice by transplanted mosaics of normal and Gsα mutated skeletal progenitor cells. J Clin Invest 1998; 101: 1737–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Riminucci M, Collins MT, Fedarko NS, et al. FGF‐23 in fibrous dysplasia of bone and its relationship to renal phosphate wasting. J Clin Invest 2003; 112: 683–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuznetsov SA, Cherman N, Riminucci M, Collins MT, Robey PG, Bianco P. Age‐dependent demise of GNAS‐mutated skeletal stem cells and “normalization” of fibrous dysplasia of bone. J Bone Miner Res 2008; 23: 1731–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sacchetti B, Funari A, Michienzi S, et al. Self‐renewing osteoprogenitors in bone marrow sinusoids can organize a hematopoietic microenvironment. Cell 2007; 131: 324–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Riminucci M, Saggio I, Robey PG, Bianco P. Fibrous dysplasia as a stem cell disease. J Bone Miner Res 2006; 21 (Suppl 2): P125–P131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rodriguez‐Lebron E, Paulson HL. Allele‐specific RNA interference for neurological disease. Gene Ther 2006; 13: 576–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miller VM, Xia H, Marrs GL, et al. Allele‐specific silencing of dominant disease genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 7195–7200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. Stable suppression of tumorigenicity by virus‐mediated RNA interference. Cancer Cell 2002; 2: 243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brummelkamp TR, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science 2002; 296: 550–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Piersanti S, Sacchetti B, Funari A, et al. Lentiviral transduction of human postnatal skeletal (stromal, mesenchymal) stem cells: in vivo transplantation and gene silencing. Calcif Tissue Int 2006; 78: 372–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhyan RK, Gerasimov UV. Bone marrow osteogenic stem cells: in vitro cultivation and transplantation in diffusion chambers. Cell Tissue Kinet 1987; 20: 263–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bianco P, Riminucci M, Majolagbe A, et al. Mutations of the GNAS1 gene, stromal cell dysfunction, and osteomalacic changes in non‐McCune‐Albright fibrous dysplasia of bone. J Bone Miner Res 2000; 15: 120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuznetsov SA, Krebsbach PH, Satomura K, et al. Single‐colony derived strains of human marrow stromal fibroblasts form bone after transplantation in vivo. J Bone Miner Res 1997; 12: 1335–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wiznerowicz M, Trono D. Conditional suppression of cellular genes: lentivirus vector‐mediated drug‐inducible RNA interference. J Virol 2003; 77: 8957–8961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amendola M, Venneri MA, Biffi A, Vigna E, Naldini L. Coordinate dual‐gene transgenesis by lentiviral vectors carrying synthetic bidirectional promoters. Nat Biotechnol 2005; 23: 108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wedegaertner PB, Bourne HR, von Zastrow M. Activation‐induced subcellular redistribution of Gs alpha. Mol Biol Cell 1996; 7: 1225–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bianco P, Kuznetsov SA, Riminucci M, Gehron Robey P. Postnatal skeletal stem cells. Methods Enzymol 2006; 419: 117–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klein D. Quantification using real‐time PCR technology: applications and limitations. Trends Mol Med 2002; 8: 257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Y, Maciejewski BS, Lee N, et al. Strain‐induced fetal type II epithelial cell differentiation is mediated via cAMP‐PKA‐dependent signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006; 291: L820–L827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reusch JE, Klemm DJ. Inhibition of cAMP‐response element‐binding protein activity decreases protein kinase B/Akt expression in 3T3‐L1 adipocytes and induces apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 1426–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reusch JE, Colton LA, Klemm DJ. CREB activation induces adipogenesis in 3T3‐L1 cells. Mol Cell Biol 2000; 20: 1008–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Petersen RK, Madsen L, Pedersen LM, et al. Cyclic AMP (cAMP)‐mediated stimulation of adipocyte differentiation requires the synergistic action of Epac‐ and cAMP‐dependent protein kinase‐dependent processes. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28: 3804–3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Watkins DC, Rapiejko PJ, Ros M, Wang H, Malbon CC. G protein mRNA levels during adipocyte differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1989; 165: 929–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang H, Watkins DC, Malbon CC. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides to Gs protein alpha subunit sequence accelerate differentiation of fibroblasts to adipocytes. Nature 1992; 358: 334–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Corsi A, Collins MT, Riminucci M, et al. Osteomalacic and hyperparathyroid changes in fibrous dysplasia of bone: core biopsy studies and clinical correlations. J Bone Miner Res 2003; 18: 1235–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Riminucci M, Kuznetsov SA, Cherman N, Corsi A, Bianco P, Gehron Robey P. Osteoclastogenesis in fibrous dysplasia of bone: in situ and in vitro analysis of IL‐6 expression. Bone 2003; 33: 434–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marie PJ, de Pollak C, Chanson P, Lomri A. Increased proliferation of osteoblastic cells expressing the activating Gs alpha mutation in monostotic and polyostotic fibrous dysplasia. Am J Pathol 1997; 150: 1059–1069. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stanton RP, Hobson GM, Montgomery BE, Moses PA, Smith‐Kirwin SM, Funanage VL. Glucocorticoids decrease interleukin‐6 levels and induce mineralization of cultured osteogenic cells from children with fibrous dysplasia. J Bone Miner Res 1999; 14: 1104–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huang XP, Song X, Wang HY, Malbon CC. Targeted expression of activated Q227L G(α)(s) in vivo. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2002; 283: C386–C395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lader AS, Xiao YF, Ishikawa Y, et al. Cardiac Gsα overexpression enhances L‐type calcium channels through an adenylyl cyclase independent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95: 9669–9674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lania A, Persani L, Ballare E, Mantovani S, Losa M, Spada A. Constitutively active Gsα is associated with an increased phosphodiesterase activity in human growth hormone‐secreting adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83: 1624–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jang IS, Juhnn YS. Adaptation of cAMP signaling system in SH‐SY5Y neuroblastoma cells following expression of a constitutively active stimulatory G protein alpha, Q227L Gsα. Exp Mol Med 2001; 33: 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nemoz G, Sette C, Hess M, Muca C, Vallar L, Conti M. Activation of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases in FRTL‐5 thyroid cells expressing a constitutively active Gsα. Mol Endocrinol 1995; 9: 1279–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oki N, Takahashi SI, Hidaka H, Conti M. Short term feedback regulation of cAMP in FRTL‐5 thyroid cells. Role of PDE4D3 phosphodiesterase activation. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 10831–10837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Persani L, Borgato S, Lania A, et al. Relevant cAMP‐specific phosphodiesterase isoforms in human pituitary: effect of Gsα mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86: 3795–3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]