Abstract

Background

Frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA) has frequently been reported as potential discriminator between depressed and healthy individuals, although contradicting results have been published. The aim of the current study was to provide an up to date meta-analysis on the diagnostic value of FAA in major depressive disorder (MDD) and to further investigate discrepancies in a large cross-sectional dataset.

Methods

SCOPUS database was searched through February 2017. Studies were included if the article reported on both MDD and controls, provided an FAA measure involving EEG electrodes F3/F4, and provided data regarding potential covariates. Hedges' d was calculated from FAA means and standard deviations (SDs). Potential covariates, such as age and gender, were explored. Post hoc analysis was performed to elucidate interindividual differences that could explain interstudy discrepancies.

Results

16 studies were included (MDD: n = 1883, controls: n = 2161). After resolving significant heterogeneity by excluding studies, a non-significant Grand Mean effect size (ES) was obtained (d = − 0.007;CI = [− 0.090]–[0.075]). Crosssectional analyses showed a significant three-way interaction for Gender × Age × Depression severity in the depressed group, which was prospectively replicated in an independent sample.

Conclusions

The main result was a non-significant, negligible ES, demonstrating limited diagnostic value of FAA in MDD. The high degree of heterogeneity across studies indicates covariate influence, as was confirmed by crosssectional analyses, suggesting future studies should address this Gender × Age × Depression severity interaction. Upcoming studies should focus more on prognostic and research domain usages of FAA rather than a pure diagnostic tool.

Keywords: Depression, MDD, Frontal alpha asymmetry, EEG, Electroencephalogram, Meta-analysis

Highlights

-

•

The validity of FAA as diagnostic biomarker for depression should be questioned.

-

•

A reversed direction of FAA is found in older-aged severely depressed men and women.

-

•

Caution is advised regarding EEG recording and processing characteristics.

1. Introduction

With a lifetime prevalence of 16.2% in the United States, major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common disorder affecting many people (Kessler et al., 2003). Projections for 2030, reported by the WHO, show that MDD will become the second most debilitating disease worldwide (Mathers and Loncar, 2006). However, despite many pursuits of research groups into improving diagnostics and prognostics, MDD prevalence is still high (Patten et al., 2016). Improving differential diagnostic procedures should lead to a more reliable distinction between MDD and other mental disorders with overlapping symptoms, ultimately enabling better prognosis with more effective treatment.

Changes in affect, in particular a depressed mood, are one of the diagnostic criteria of MDD (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 2013). A model that focuses on affect, also known as the approach-withdrawal hypothesis, was developed to describe basic features of emotional affect (later described as the diathesis model by Davidson and Tomarken in 1989 (Henriques and Davidson, 1991)). According to this model, two major motivational systems in response to stimuli exist: one is appetitive whereas the other is aversive. This corresponds to positive and negative affect respectively, inducing approach or withdrawal behavior. The balance in the activation of these systems is also assumed to be reflected in differential activity in the EEG. In particular, anterior left activation (reflected by relatively diminished anterior left alpha activity, compared to right) was hypothesized to correspond with appetitive behavior (approach), and anterior right activation (reflected by relatively diminished anterior right alpha activity, compared to left) was hypothesized to correspond to aversive behavior (withdrawal) (Davidson, 1984, Kelley et al., 2017). This asymmetry between left and right frontal alpha is referred to as frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA).

Initial EEG studies comparing depressed people with controls indeed provided evidence for left-sided FAA (higher left than right frontal alpha activity) in depressed patients (Henriques and Davidson, 1991, Bell et al., 1998, Gotlib, 1998, Debener et al., 2000, Pizzagalli et al., 2002), compared to a dominant right-sided FAA in controls (Schaffer et al., 1983, Fingelkurts et al., 2006). Note that left-sided FAA is inversely related to relatively greater right than left cortical activity, as cortical processing typically results in a reduction of synchronous rhythmic activity (e.g. a reduction in alpha power). A significant correlation between FAA and Behavioral Activation System (BAS) sensitivity (of which low scores indicate a predisposition toward certain types of MDD), suggested that this pattern of FAA “…may hold prognostic value for identifying those at risk for psychopathology characterized by a deficiency in approach motivation (e.g. depression)” (Harmon-Jones and Allen, 1997). Furthermore, left-sided FAA is hypothesized to specifically expose subgroups reporting anhedonia (a common MDD symptom described as diminished interest or experience of pleasure), while anxious apprehension, related to an opposite pattern of right-sided FAA, might possibly mark another subgroup (Nusslock et al., 2015). Defining such subgroups needs further investigation.

Although recent studies have confirmed an association between MDD and FAA (Kemp et al., 2010, Jaworska et al., 2012, Beeney et al., 2014, Gollan et al., 2014), which was also reflected by two reviews (Fingelkurts and Fingelkurts, 2015, Baskaran et al., 2012), multiple methodologically sound studies have failed to confirm the diagnostic value of FAA regarding MDD and other mental illnesses (Reid et al., 1998, Kentgen et al., 2000, Knott et al., 2001, Allen et al., 2004, Deldin and Chiu, 2005, Price et al., 2008, Mathersul et al., 2008, Carvalho et al., 2011, Gold et al., 2013, Quraan et al., 2014, Kaiser et al., 2016), including the largest EEG study to date in MDD in a sample of 1008 MDD patients compared to 336 controls (Arns et al., 2016) from our research group. Questions should be raised on the uniformity and generalizability of all studies regarding FAA. This concerns technical properties of the EEG recordings and further processing of the data, as well as sample characteristics. This makes updating previous reviews and a meta-analysis relevant, with adding results of more recent studies.

A decade ago, Thibodeau et al. (2006) addressed the use of FAA in a meta-analytic review, including a maximum of 1614 adults (depressed and healthy, exact sample size is unknown), and concluded that depression is meaningfully related to relatively greater right than left frontal cortical activity at rest (left-sided FAA), with moderate weighted mean effect sizes (ES) for the depressed adults with Pearson r = 0.26 and Cohen's d = 0.54. Their meta-analysis did not include recent large methodologically sound studies and had several limitations, e.g. it included a wide range of groups defined by other characteristics than an MDD diagnosis or defined as sub-clinical MDD characteristics, FAA measures based on different scalp sites, and different types of ESs as reported in original articles. When controlling for sub-clinical MDD, the authors found an equally moderate ES for FAA with r = 0.27, indicating a limited influence of operationalization of depression. Several studies and reviews (Jaworska et al., 2012, Thibodeau et al., 2006, Hagemann et al., 1998, Davidson, 1998, Allen and Kline, 2004, Stewart et al., 2010, Segrave et al., 2011, Smith et al., 2017) have indicated that methodological aspects could explain discrepant findings, such as the EEG reference montage and frequency range considered. Further, the FAA calculation is not often discussed in studies and reviews, but varies in normalization application. Normalizing by dividing F4 − F3 by its sum (F4 + F3) enables researchers to rule out interindividual EEG differences like individual EEG power (as a result of skull thickness for instance).

The purpose of the current study was to provide an up to date meta-analysis, further clarifying the role of FAA in MDD using a standardized approach. This is achieved by calculating a weighted mean effect size (ES) only based on original means and standard deviations (SDs), obtained from EEG electrode F3 and F4 only and using a more homogenous sample with clear inclusion criteria (MDD vs. non-MDD only, excluding sub-clinical samples). Furthermore, we also used data from a large cross-sectional dataset (MDD: n = 938, Controls: n = 306) to investigate interindividual differences, and the impact of methodological aspects such as EEG montaging and use of normalization.

2. Material and methods

A literature search was carried out in SCOPUS for the period up until February 2017, using the query “depression AND EEG OR electroencephalogram AND alpha asymmetry”, which yielded 172 hits. The database search outlined above was supplemented by manual searches. To identify additional publications, we further inspected reference lists from prior meta-analyses (Thibodeau et al., 2006) and reviews (Fingelkurts and Fingelkurts, 2015, Jesulola et al., 2015). PRISMA guidelines for conducting and reporting systematic reviews were followed during this analysis (Moher et al., 2009).

Studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (a) DSM(-IV) diagnosis of MDD or MDD classification after a structured clinical interview using the SCID or MINI; (b) availability of mean, standard deviation (SD), and sample size of resting FAA (electrode F4 minus F3); (c) availability of a healthy control group; (d) reporting of EEG reference montage; (e) published in English. When means, SDs and/or sample sizes were not provided in the article, authors were e-mailed to request the relevant data. Additional subject information on the following variables was gathered: Mean age and SD, comorbid classifications (% and type of comorbidity), comorbid anxiety, medication status (% receiving an antidepressant), gender (% female), depression severity mean and SD. For each study, we also recorded the year of publication, reference montage, resting EEG condition (eyes open (EO), eyes closed (EC), or both), recording length, alpha bandwidth and continent where the study is carried out.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0. MetaWin 2.1 (Rosenberg et al., 2000) was used to conduct the meta-analysis and generate all variables of interest. ESs (the standardized mean difference Hedges' d) were calculated based on the FAA statistic from the MDD group and control group means and SDs. This ES is a scale-free statistic, thereby allowing comparison of scores from various studies. A grand mean ES was calculated with a 95% confidence interval (CI) providing the weighted mean ES for all studies. Larger ES values indicate stronger clinical relevance. Furthermore, Qt (heterogeneity of ESs), and the fail-safe number (Rosenthal's method: α < 0.05, and Orwin's method) were calculated. The fail-safe number is the number of studies, indicating how many unpublished null findings are needed to render an effect non-significant. When the total heterogeneity of a sample (Qt) was significant – indicating that the variance among ESs is greater than expected by sampling error – the study contributing most to the significance of the Qt value was excluded from further analysis for that variable until the Qt value was no longer significant. This was done for a maximum of three iterations. If more than three studies needed to be excluded to obtain a non-significant Qt value, then other explanatory variables for the effects had to be assumed (Rosenberg et al., 2000) and were investigated in post hoc tests.

To investigate specific interstudy differences (or a lack thereof), the cross-sectional dataset of Arns et al. (2016) was used to elucidate interindividual differences that could drive differences between studies. To this end, main and interactional effects of group, gender, age, depression severity (HRSD-17), and anxiety severity (HAM-A), were investigated through univariate ANCOVAs. To test the stability of the significant results in this paper across EEG reference montages and different FAA definitions, FAA was also analyzed after re-referencing to Cz and the linked ears from the original average reference montage.

3. Results

3.1. Meta-analysis

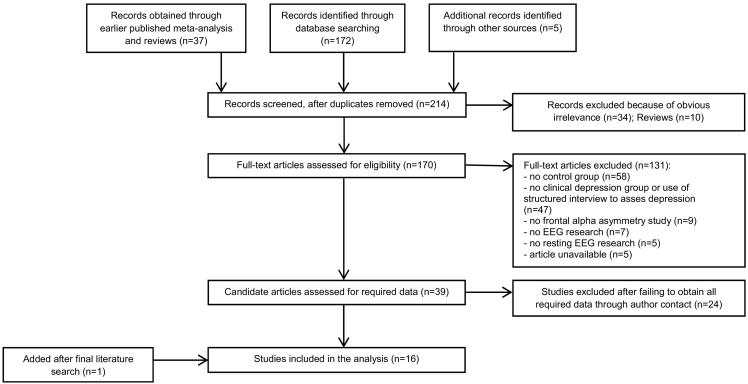

A total of 214 studies were identified between January 1998 and July 2016. One additional relevant study was identified out of studies covered by an earlier meta-analysis (Thibodeau et al., 2006) and reviews (Fingelkurts and Fingelkurts, 2015, Baskaran et al., 2012, Jesulola et al., 2015). A final search conducted in February 2017 yielded eight new hits, resulting in one extra study in the meta-analysis. See Fig. 1 for a flow diagram of the inclusion process.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the inclusion process.

Most excluded studies were not selected due to the absence of a control group (n = 58) or the absence of a clinical MDD group (n = 47). 16 studies (Jaworska et al., 2012, Beeney et al., 2014, Gollan et al., 2014, Carvalho et al., 2011, Kaiser et al., 2016, Arns et al., 2016, Stewart et al., 2010, Segrave et al., 2011, Baehr et al., 1998, Brzezicka et al., 2016, Cantisani et al., 2015, Deslandes et al., 2008, Gordon et al., 2010, Quinn et al., 2014, Liu et al., 2016, Keeser et al., 2013, Saletu et al., 1996) met all inclusion criteria and were included in this meta-analysis, see Table 1 for an overview. Note that only one study was included in both the previous meta-analysis by Thibodeau et al. (2006) and the current meta-analysis, because most of the other previous studies were either based on a depression group defined by solely a severity measure (no official diagnosis), on continuous depression severity measures (no control group), or the requested means were not available.

Table 1.

Overview of all included studies in the meta-analysis, covering the period 1996–2017.

| No | Study | ES | FAA MDD Group |

FAA controls Group |

EEG details |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meana | SD | n | Meana | SD | n | Reference montage | EO/ECb | Recording length (s) | Alpha band (Hz) | FAA measure | |||

| 1 | Arns et al., 2016 | 0.059 | 0.002 | 0.13 | 938 | − 0.005 | 0.10 | 306 | CAd | EC | 120 | 8–13 | (F4 − F3)/(F4 + F3) |

| 2 | Baehr et al., 1998 | − 1.345 | − 1.160 | 7.82 | 13 | 9.760 | 7.86 | 11 | Cz | EC | 300 | 8–13 | (F4 − F3)/(F4 + F3) |

| 3 | Beeney et al., 2014 | − 0.261 | 0.020 | 0.36 | 13 | 0.090 | 0.18 | 21 | Cz | EO/EC | 480 | 8–13 | F4 − F3 |

| 4 | Brzezicka et al., 2016 | − 0.254 | 0.799 | 1.36 | 26 | 1.109 | 1.01 | 26 | CSDd | EC | 300 | 8–13 | F4 − F3 |

| 5 | Cantisani et al., 2015 | − 0.834 | − 0.127 | 0.34 | 20 | 0.102 | 0.17 | 19 | CA | EC | 300 | 8–12.5 | F4 − F3 |

| 6 | Carvalho et al., 2011 | 0.533 | 0.059 | 0.11 | 12 | 0.003 | 0.08 | 7 | LEd | EC | 480 | 8–12.9 | F4 − F3 |

| 7 | Deslandes et al., 2008 | − 0.283 | − 0.179 | 0.28 | 22 | − 0.105 | 0.21 | 14 | LE | EC | 480 | 8–13 | F4 − F3 |

| 8 | Gollan et al., 2014 | 0.480 | 0.430 | 0.73 | 37 | 0.160 | 0.27 | 35 | LE | EO/EC | 480 | 8–13 | F4 − F3 |

| 9 | Gordon et al., 2010/Quinn et al., 2014 | − 0.072 | − 0.010 | 0.15 | 93 | − 0.002 | 0.11 | 1037 | CA | EC | 120 | 8–13 | F4 − F3 |

| 10 | Jaworska et al., 2012 | − 0.166 | − 0.005 | 0.16 | 53 | 0.034 | 0.30 | 43 | CA, Cz, LE | EC | 360 | 8–13 | F4 − F3 |

| 11 | Kaiser et al., 2016 | − 0.006 | 0.212 | 0.20 | 14 | 0.213 | 0.12 | 14 | LE | EC | 180 | 8.9–10.9 | F4 − F3 |

| 12 | Liu et al., 2016 | − 0.307 | 0.000 | 0.06 | 141 | 0.018 | 0.05 | 113 | LE | EO/EC | 360 | 7.8–12.7 | F4 − F3 |

| 13 | Keeser et al., 2013 | 0.005 | − 0.016 | 0.09 | 233 | − 0.016 | 0.07 | 291 | CA | EC | 600 | 8–12 | (F4 − F3)/(F4 + F3) |

| 14 | Saletu et al., 1996 | − 0.600 | − 0.014 | 0.07 | 60 | 0.031 | 0.08 | 29 | CA | ECc | 180 | 7.5–13 | (F4 − F3)/(F4 + F3) |

| 15 | Segrave et al., 2011 | 0.443 | 0.065 | 0.10 | 16 | 0.010 | 0.14 | 18 | CA, Cz | EO/EC | 360 | 8–13 | F4 − F3 |

| 16 | Stewart et al., 2010 | 0.066 | 0.013 | 0.08 | 143 | 0.007 | 0.09 | 163 | CA, Cz, LE, CSD | EO/EC | 480 | 8–13 | F4 − F3 |

| No | Age mean (SD) |

Comorbidity | % female | % medicated (MDD) | MDD severity measure | Severity mean (SD) |

Continent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDD | Controls | MDD | Controls | ||||||

| 1 | 37.6 (12.6) | 36.9 (13.1) | Anxe (n = 62), Soc phobe (n = 105) | 57% | 0% | HRSD | 22 (4.1) | 1.2 (1.7) | International |

| 2 | 43.5 (7) | 44.2 (13.3) | Unknown | n/a | 17% | BDI | 21.9 (9.2) | 3.4 (2.9) | North-America |

| 3 | 32.1 (8.8) | 27.8 (11.7) | Anx (n = 4), PTSD (n = 1) | 100% | n/a | BDI-II | 18.5 (9.4) | 2.9 (2.8) | North-America |

| 4 | 28 (8.3) | 24.9 (5.2) | Unknown | 60% | n/a | BDI | 20.5 (8.3) | 2.9 (2.5) | Europe |

| 5 | 43.4 (14) | 41.1 (13.8) | Unknown | 54% | 95% | HRSD | 25.5 (5) | n/a | Europe |

| 6 | 71 (7.8) | 72 (9.2) | None | 63% | 100% | BDI-II | 16.4 (4.4) | 2 (2.3) | South-America |

| 7 | 71.6 (1.2) | 72.4 (1.7) | None | 94% | 100% | HRSDf | 9.4 (1.5) | 1.1 (2.6) | South-America |

| 8 | 36.2 (12.4) | 35.1 (13.7) | Unknown | 63% | 0% | IDS-Cf | 33.7 (7.7) | 2.3 (2.6) | North-America |

| 9 | 40.7 (14.8) | 40.2 (17.1) | None | 50% | 0% | DASS | 13.8 (5.1) | 1.5 (2.2) | International |

| 10 | 40.7 (11.9) | 36.6 (9.9) | Anx (n = 8) | 54% | 0% | MDD: HRSDf Control: BDI-II |

22.4 (5.1) | 4.4 (5) | North-America |

| 11 | 80.5 (5.7) | 80.9 (7.0) | Unknown (no Anx) | 100% | Unknown | HADS-D | 7.7 (2.5) | 2.0 (1.4) | Europe |

| 12 | 33.1 (12.1) | 32.6 (12.5) | Anx (n = 74) | 82% | 37% | HRSD | 26.3 (7.8) | 3.2 (4.9) | North-America |

| 13 | 22.3 (14.3) | 46.3 (14.2) | Adje (n = 3), Sube (n = 3), Anx (n = 1), Depee (n = 1), OCD (n = 1) | 56% | 63% | n/a | n/a | n/a | Europe |

| 14 | 51.1 (3.1) | 53.4 (2.9) | Unknown (n = 2) | 100% | 0% | HRSD | 18.3 (5.7) | 2.9 (2.4) | Europe |

| 15 | 40.8 (11.4) | 42.1 (13) | None | 100% | 44% | BDI-IIf | 39.3 (10.6) | 2.1 (2.5) | Australia |

| 16 | 19.1 (0.1) | Unknown | None | 69% | 0% | HRSDf | 11.1 (1.1) | 4 (0.6) | North-America |

In the occurrence of multiple reference montages, one is selected for calculation of the grand mean in the following order of priority: CA, Cz, Mas, CSD.

When both EO and EC data was available, EC was used for further analysis.

An auditory stimulus was presented when a drowsiness pattern was visible in the EEG.

Abbreviations used: CA = common average reference, CSD = current source density, LE = linked ears.

Abbreviations used: Anx = anxiety, Soc phob = social phobia, Adj = adjustment disorder, Sub = substance abuse, Depe = dependent personality disorder.

Multiple depression severity measures available, one is selected in the following order of priority: HRSD/HAM-D, BDI-II, MADRS, IDS-C.

Due to overlapping samples of Gordon et al. (2010) and Quinn et al. (2014), original data of these studies were requested and combined to prevent overlapping samples, now referred to as Gordon/Quinn. Note that Gordon et al. originally reported on electrode FC4 and FC3 and Quinn et al. on the more frequently used F4 and F3. Considering the inclusion criteria of this meta-analysis, only F4 − F3 data were merged (this data was provided by BRAINnet). FAA Means, SDs and n were recalculated for the studies of Arns et al. (2016) (analysis of original data for EC only as well as age means and SDs), Stewart et al. (2010) (merging of subgroup data), and Brzezicka et al. (2016) (merging of individual data). Additional statistics (means of (F4 − F3)/(F4 + F3) and SDs) and subject data were calculated for the data provided by Daniel Keeser of the neurophysiological research group of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University of Munich, Germany (Keeser et al., 2013). These data were updated with data from newly included subjects since the publishing of the cited conference abstract.

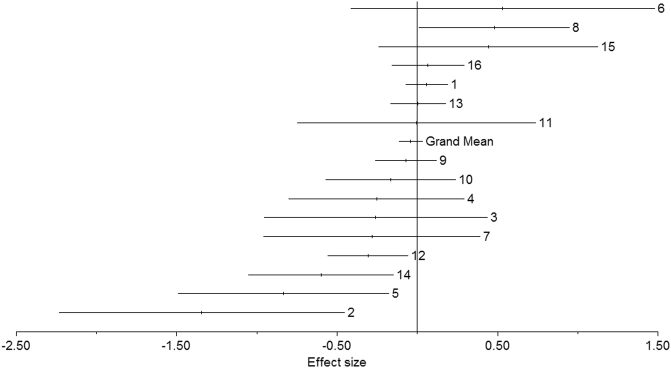

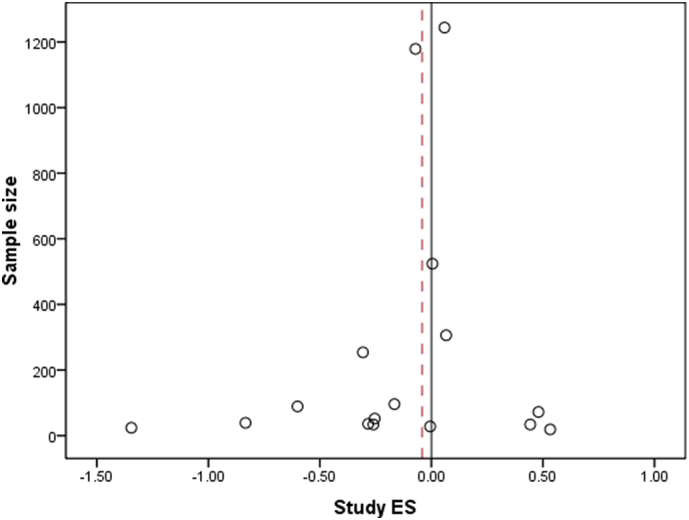

A total of 1883 MDD subjects and 2161 control subjects was included in the meta-analysis. A fixed-effects model meta-analysis yielded a significant heterogeneity test (Qt = 37.65 p = 0.001), a non-significant grand mean ES of − 0.041 (CI = [− 0.1204–0.0375]), and a fail-safe number of 11.4 (Rosenthal's method) and 0 (Orwin's method). The forest plot in Fig. 2 and funnel plot in Fig. 3 show a graphical overview of the ESs and grand mean.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the effect sizes (ES) of all included studies and the grand mean ES for all studies. The grand mean ES after resolving heterogeneity was − 0.007 (not significant). Numbers correspond to study numbers in Table 1.

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot of the study effect sizes (ES) and corresponding sample sizes, with the black line indicating x = 0 and the dotted line indicating the grand mean ES = − 0.041. Note that the largest studies with sample size N > 200 all approach the same ES close to 0, suggesting that a sample size of 300 and larger is required to obtain stable and biologically plausible effects for FAA in MDD.

Exclusion of three studies (Baehr et al., 1998, Cantisani et al., 2015, Saletu et al., 1996) abolished the significant heterogeneity, resulting in a non-significant grand mean ES of − 0.007 (CI = [− 0.090–0.075]) and a fail-safe number of 0 (Rosenthal's method) and 0 (Orwin's method). In subsequent post hoc analysis, we attempted to identify the source of heterogeneity (outlined below).

3.2. Post hoc tests

Post hoc, the influence of several potential moderators was investigated. Detailed results can be found in the Appendix. One potentially important moderator is the choice of the reference montage, which differs across the included studies. We performed post hoc tests where the relationship between study ES and reference montage was investigated. This did not result in significant ESs, or left the analyses with an insufficient number of studies, and therefore insufficient power, to achieve reliable results. Additional analyses (with combined montages as well as separated analyses per type of montage) between study ES and most potential moderators demonstrated no significant correlations, including anxiety. This was investigated further in one of the included studies by Arns et al. (2016), who found no changes in results after excluding subjects diagnosed with comorbid anxiety (female responders showed greater alpha (less cortical activity) over the right frontal site, whereas non-remitters showed the opposite asymmetry).

3.3. Cross-sectional analysis

To explain the different study outcomes, we used 1244 participants (out of 1344 subjects, these had successful EEGs combined with BDI scores) from the cross-sectional dataset iSPOT-D (Arns et al., 2016) to extract candidate factors that could influence FAA or explain differences between studies. No significant contribution of singular variables to FAA was found through univariate ANCOVA (variables included group and gender as fixed factors, and age, depression severity, and anxiety as covariates). Although no significant interaction effect was found for Group × Gender × Age × Severity, within the depressed group, a significant three-way interaction of Gender × Age × Severity was found (F(1,930) = 6.096, p = 0.014) when these variables were exclusively part of the model, but this was not the case within the control group. Replacing depression severity with anxiety severity in this model did not yield any significant effects. To study the stability of Gender × Age × Severity across datasets, the same analysis was prospectively conducted in the Gordon/Quinn dataset (MDD: n = 93, controls: n = 1037). Note that one-sided testing of the replication of an interaction effect was not possible through ANOVA. Nevertheless, considering the a priori hypothesis and the smaller replication sample at hand, a more liberal criterion of p < 0.10 was employed. This replicated the significant three-way interaction effect as well (F(1,85) = 3.400, p = 0.069).

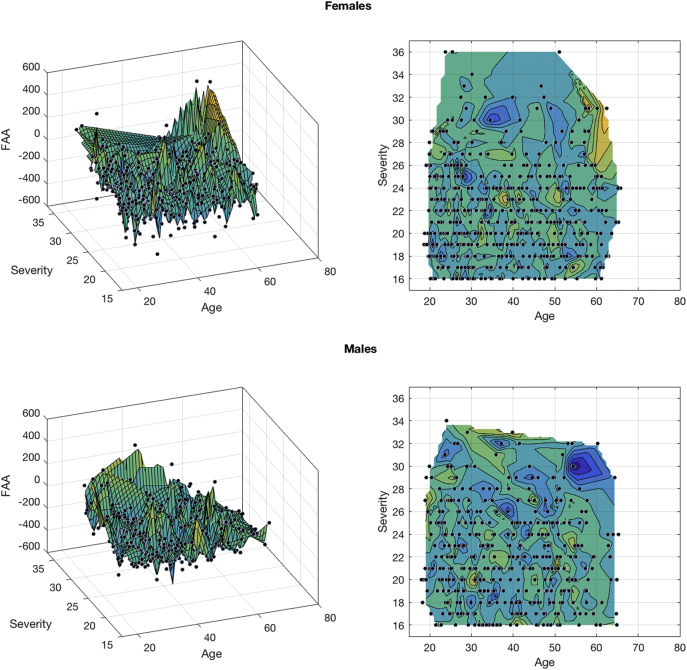

To visualize this three-way interaction, the Curve Fitting Toolbox in MATLAB 2016b (The Mathworks, Inc., Natrick, MA) was used. In Fig. 4, the linear fitting of the surface is illustrated, comparing females and males based on their FAA, age and depression severity. A pattern becomes visible where differences between females and males seem to exist for older and severely depressed subjects, especially from an age of approximately 53 years and older, with opposing effects for males compared to females. Based on these results, four groups were formed dividing young and old (< 53 and ≥ 53 years old), and moderately and severely depressed subjects (HDRS score < 24 and ≥ 24, based on recent labelling of HDRS depression scores (Zimmerman et al., 2013)). In these groups, univariate ANOVAs with gender, age, and severity as dependent variables were performed separately. No significant gender effects in FAA were found in both the young and moderately depressed groups. In the old, severely depressed group however, females had significantly higher, i.e. right sided, FAA than males (F(1,46) = 8.094, p = 0.007). This seems to drive the three-way interaction effect found earlier.

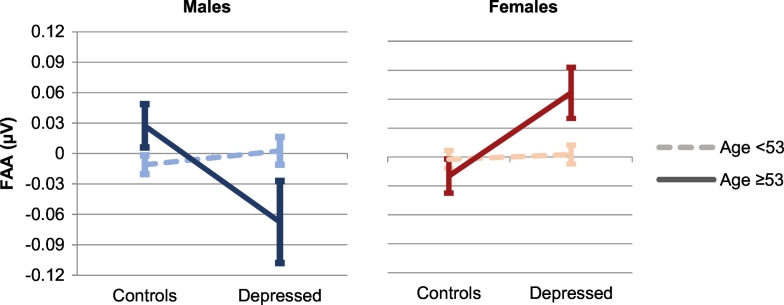

Fig. 4.

Linear fitted surface graph, visualizing the three-way interaction effect of frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA), age, and depression severity, separately for females and males.

The four defined groups were subsequently used to address the original question: Can a diagnosis of MDD be predicted using FAA? Univariate ANOVAs including only severely depressed, separately for males and females, and younger and older subjects (split up at 53 years) showed strikingly different results. While no differences between controls and depressed were found for the younger groups (n = 243 and n = 288 respectively), significant differences were found in the older groups with a severe depression, both for males and females (respectively F(1,34) = 4.806, p = 0.035, Cohen's d = 0.71 and F(1,59) = 0.6791, p = 0.012, Cohen's d = − 0.69). Fig. 5 illustrates that the direction of this effect is reversed for males and females, with relatively more left-sided FAA in depressed males, and more right-sided FAA for females. Repeating these ANOVAs by replacing severely depressed with moderately depressed yielded no significant effects.

Fig. 5.

Line graphs with error bars (representing standard error of the means) depicting the difference in frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA) between controls and severely depressed patients, separately for males and females, and < 53 years and ≥ 53 years. Positive values of FAA indicate greater alpha over right than left frontal site, negative values indicate the opposite.

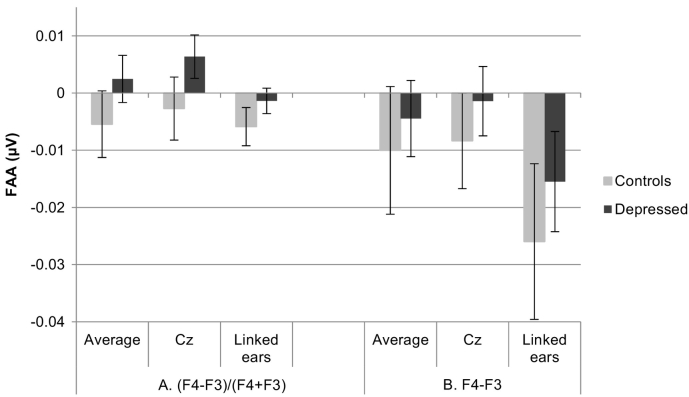

Comparing the different reference montages in the cross-sectional dataset through multivariate ANOVA did not result in significant group differences on FAA in either montage (see Fig. 6A), nor did stratification by gender, suggesting that the lack of group effects cannot be simply explained by the EEG-montage used.

Fig. 6.

A: Illustration of frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA) means and 95% error bars (representing standard error of the mean) for controls and depressed patients, separately for the three different EEG reference schemes. B: Similar to A, except for the calculation of FAA without dividing by the sum of F4 and F3. Note the differences based on EEG reference montage, but also that none of these methodological changes changed the overall MDD-control contrast to a significant difference, illustrating that these methodological aspects could yield different outcomes, but do not explain the lack of ‘diagnostic’ effect of FAA in this large sample.

To normalize interindividual differences FAA F4 minus F3 can be divided by its sum. However, most included studies calculated FAA only by the difference score F4 − F3 (see Table 1). Although two multivariate ANOVAs comparing the different methods did not yield different results of FAA in depressed and controls, the absence of sum division can result in rather large differences in raw individual FAA scores, depending on which reference scheme is applied (see Fig. 6B). However, not dividing by the sum still did not render the non-significant group effect to significance.

4. Discussion

In this meta-analysis, the diagnostic value of FAA was investigated. The small and non-significant effect size approaching zero extracted from this meta-analysis, accompanied by highly significant heterogeneity across studies, suggest that FAA is not a reliable diagnostic biomarker for MDD. Furthermore, the funnel plot in Fig. 3 suggests that at least 300 subjects need to be included to obtain a stable and biological plausible effect for FAA in MDD, confirming that most studies have been underpowered that investigated the diagnostic value of FAA (cf. Table 1).

We could not identify a single variable that reliably explained a significant portion of the variance in FAA findings across studies. Cross-sectional analyses in the large iSPOT-D sample (Arns et al., 2016) were performed to explore possible candidate variables that have been suggested to explain differences between studies e.g. EEG reference montage, calculation of FAA with or without normalization, effects and interactions of gender, depression severity, anxiety severity, etc. A significant interaction effect of age, gender, and depression severity was found in depressed patients as visualized in Fig. 4, Fig. 5, and also prospectively replicated in an independent sample (Gordon et al., 2010, Quinn et al., 2014). This interaction implicated more right-sided FAA (relatively more cortical activity on the left than right frontal site) in severely depressed women aged 53 years and older, in contrast to relatively more left-sided FAA in severely depressed men of the same age. This finding suggests that when unequal gender distributions, age-ranges, and depression severity are studied, this may result in non-generalizable results. This confirms our hypothesis that a high level of heterogeneity in FAA in the depression population exists, which is in line with previous methodologically sound studies (Kentgen et al., 2000, Knott et al., 2001, Deldin and Chiu, 2005, Price et al., 2008, Quraan et al., 2014). Consequently, the lack of consistency in the results is not in line with the approach-withdrawal model, which was hypothesized to predict a meaningful relationship between the degree of approach behavior and affect on one hand, and FAA on the other hand. Note that Davidson (1998) emphasized that his previously developed model of approach and withdrawal systems “…was never intended as a model of depression or any other form of psychopathology for that matter”. Differences in frontal asymmetry may thus reflect individual differences in affective style rather than being a pure diagnostic marker for MDD (Davidson, 1998), thereby warranting its use more along the lines of Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) or Precision Medicine (Cuthbert, 2014). This is in line with the clear prognostic role of FAA, where a right frontal dominant FAA was associated with response to SSRIs and left frontal dominant FAA was associated with non-response to SSRIs in females (Arns et al., 2016). Translating this knowledge to prognostic methods in clinical practice, will allow health care professionals to personalize mental health treatments.

To our knowledge, our finding, comprising three different factors (gender, age, depression severity) has not been reported before. Previous studies have not always included all three variables, or sample sizes might have been too small to detect this three-way interaction. Interestingly, a closely related interaction effect between gender and severity was recently reported by Jesulola et al. (2017), reflecting an FAA pattern in severely depressed females, that is opposite to the traditionally hypothesized direction of FAA in MDD, which is lacking in males. Note that age was not taken into account here. Previous studies in elderly showed no group differences in FAA (Kaiser et al., 2016), even when controlling for depression severity (Carvalho et al., 2011, Deslandes et al., 2008). On the one hand, age effects are not ruled out because increased neural heterogeneity in older adults has been found (Karch et al., 2015). Albeit, a large dataset of 6029 subjects showed that FAA does not change across the lifespan in a healthy population (Hashemi et al., 2016). Furthermore, significant differences between healthy and depressed individuals were reported in younger samples from this meta-analysis (mean sample ages of 29.4 and 35.7 (Beeney et al., 2014, Gollan et al., 2014)), but most likely these studies were underpowered (see funnel plot in Fig. 3). Therefore, the literature regarding more left-sided alpha in young and middle-aged depressed cannot be explained by current results. Other explanatory variables must be assumed, as the high level of heterogeneity suggests (Rosenberg et al., 2000).

Although the most frequently used EEG montage in the included studies is the average reference, other montages like Cz, and linked ears referencing are also common practice. Davidson (1998) and Hagemann et al. (1998) both made a strong case for enabling more consistent study outcomes by using average reference in FAA research. A promising reference-free methodology in FAA research is current source analysis (e.g. (Brzezicka et al., 2016)). In particular Current Source Density (CSD) is recommended for advanced EEG analysis by both Kayser and Tenke (2015) and Stewart et al. (2014), avoiding the question how to reference data and by providing a more distinct topography. As the current meta-analysis contains no comparable CSD studies, we can only recommend the use of the average reference, based on our post hoc analyses. Not only its ability to correct for strong occipital alpha, but also the topographical proximity of Cz to F3 and F4, and the possible insensitivity to subtle but meaningful differences of the linked ears reference, make the average reference the best candidate. An additional advantage is its relative insensitivity for the choice whether or not the FAA difference score (F4 − F3) is divided by its sum (F4 + F3), as visualized in Fig. 6. This choice has considerably more effect when applied to linked ears referenced data. Although the relative difference in FAA between depressed patients and controls is similar in any combination of reference scheme and FAA measure, we recommend the use of (F4 − F3)/(F4 + F3). Not dividing by its sum has large consequences for the degree of negativity of FAA in both groups.

A strong element in this meta-analysis was the calculation of an ES based on each study's FAA means and SDs, as well as the application of clear inclusion criteria improving the consistency across studies. Unfortunately, this resulted in considerably fewer included studies than Thibodeau et al. (2006), albeit this meta-analysis included a substantially larger overall sample size (k = 16 vs. k = 24 and n = 4044 vs. n = 1614 for our meta-analysis and the meta-analysis by Thibodeau respectively). Furthermore, a consequence of excluding most previously included studies by Thibodeau et al., the current is a completely new meta-analysis with respect to the entered datasets (apart from one study), instead of an extended meta-analytic database. This might have caused a difference in findings. Nonetheless, we consider the consistency across studies superior to the quantity of studies. The inclusion of only 16 studies did make it difficult to compare studies based on several characteristics, regularly leaving us with groups too small to come to reliable conclusions. In part, this was overcome by performing cross-sectional analyses on the largest dataset in this meta-analysis (Arns et al., 2016) and cross-validation in a second dataset (Gordon/Quinn (Gordon et al., 2010, Quinn et al., 2014)). This enabled us to unravel patterns that would not have become visible in a meta-analysis only, making the value of gender, age and MDD severity in relation to FAA evident, and need to be taken into account in future studies investigating FAA in MDD. The current data did not allow for identifying additional subgroups showing symptoms such as anhedonia, comorbid anxious apprehension, panic or social phobia, but further studying contribution of these specific clusters of symptoms to FAA, could benefit the personalization of mental health treatments. Furthermore, a few state emotion manipulations in EEG paradigms show greater FAA group differences than resting state EEG paradigms (Stewart et al., 2014). Although the number of these studies is too small to include in the current study, this method could enlarge the chance of determining subgroups. Finally, reliability and consistency of measuring FAA might be improved by EEG recording across multiple sessions, as FAA is found to be moderately stable across time (Allen et al., 2004, Vuga et al., 2006), as originally suggested by Davidson (1998). For a detailed and recent overview of studies on hemispheric asymmetry in depression, please see the review by Bruder et al. (2017).

The importance of replication of results has become increasingly evident, because many scientific claims in psychology and psychiatry are rebutted, or more intricate systems appear to be implicated. New insights suggest a different application of FAA, actually utilizing the interindividual variation in this biomarker. For instance, the prediction of antidepressant treatment outcome using gender specific alpha asymmetry was first reported by Bruder et al. (2001) and replicated by Arns et al. (2016). Future studies into the use of FAA as a biomarker could help improve understanding of the basic dimensions underlying human behavior, and ultimately lead to improving treatment. This being one of the purposes of the use of Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), future studies should be in line with this approach, in order to demonstrate the clinical relevance of FAA more as a domain criterion or prognostic biomarker, rather than a ‘diagnostic’ marker. We emphasize that individual differences should not be ignored, but rather embraced, thereby potentially leading to optimized characterization of relevant subgroups and subsequent implications for a personalized treatment for the increasing number of depressed patients.

Acknowledgements

Preliminary results of this meta-analysis were presented at the 19th Biennial Conference of the International Pharmaco-EEG Society, October 2016. We acknowledge the support of Michelle Wang, Chris Spooner and Donna Palmer in obtaining all relevant data of the cross-sectional datasets, Ryan Thibodeau in further clarifying the first meta-analysis, as well as Aneta Brzezicka and Olga Kamińska, Andrea Cantisani, Stewart Shankman, Jennifer Stewart and John Allen, Andréa Deslandes and Alessandro Carvalho, Natalia Jaworska, Andreas Kaiser, Daniel Keeser, Joseph Beeney, and Peter Anderer for providing additional data requested.

Financial disclosures

NV, MV and MA report no relevant financial disclosures. MvP is a co-founder of Clinical Science Systems. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2017.07.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Allen J.J.B., Kline J.P. Frontal EEG asymmetry, emotion, and psychopathology: the first, and the next 25 years. Biol. Psychol. 2004;67(1–2):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J.J., Urry H.L., Hitt S.K., Coan J.A. The stability of resting frontal electroencephalographic asymmetry in depression. Psychophysiology. 2004, Mar;41(2):269–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2003.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arns M., Bruder G., Hegerl U., Spooner C., Palmer D.M., Etkin A. EEG alpha asymmetry as a gender-specific predictor of outcome to acute treatment with different antidepressant medications in the randomized ispot-d study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016;127:509–519. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baehr E., Rosenfeld J.P., Baehr R., Earnest C. Comparison of two EEG asymmetry indices in depressed patients vs. normal controls. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1998, Dec;31(1):89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(98)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskaran A., Milev R., McIntyre R. The neurobiology of the EEG biomarker as a predictor of treatment response in depression. Neuropharmacology. 2012, May 5;63(4):507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeney J.E., Levy K.N., Gatzke-Kopp L.M., Hallquist M.N. EEG asymmetry in borderline personality disorder and depression following rejection. Personal. Disord. 2014, Apr;5(2):178–185. doi: 10.1037/per0000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell I.R., Schwartz G.E., Hardin E.E., Baldwin C.M., Kline J.P. Differential resting quantitative electroencephalographic alpha patterns in women with environmental chemical intolerance, depressives, and normals. Biol. Psychiatry. 1998, Mar 1;43(5):376–388. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder G.E., Stewart J.W., Tenke C.E., McGrath P.J., Leite P., Bhattacharya N., Quitkin F.M. Electroencephalographic and perceptual asymmetry differences between responders and nonresponders to an SSRI antidepressant. Biol. Psychiatry. 2001, Mar 1;49(5):416–425. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder G.E., Stewart J.W., McGrath P.J. Right brain, left brain in depressive disorders: clinical and theoretical implications of behavioral, electrophysiological and neuroimaging findings. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, Jul;78:178–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezicka A., Kamiński J., Kamińska O.K., Wołyńczyk-Gmaj D., Sedek G. Frontal EEG alpha band asymmetry as a predictor of reasoning deficiency in depressed people. Cogn. Emot. 2016, Apr;18:1–11. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1170669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantisani A., Koenig T., Stegmayer K., Federspiel A., Horn H., Müller T.J. EEG marker of inhibitory brain activity correlates with resting-state cerebral blood flow in the reward system in major depression. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00406-015-0652-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A., Moraes H., Silveira H., Ribeiro P., Piedade R.A., Deslandes A.C. EEG frontal asymmetry in the depressed and remitted elderly: is it related to the trait or to the state of depression? J. Affect. Disord. 2011, Mar;129(1–3):143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert B.N. Translating intermediate phenotypes to psychopathology: the NIMH research domain criteria. Psychophysiology. 2014, Dec;51(12):1205–1206. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R.J. Affect, cognition, and hemispheric specialization. In: Izard C.E., Kagan J., Zajonc R.B., editors. Emotion, Cognition, and Behavior. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1984. pp. 320–365. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R.J. Anterior electrophysiological asymmetries, emotion, and depression: conceptual and methodological conundrums. Psychophysiology. 1998, Sep;35(5):607–614. doi: 10.1017/s0048577298000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debener S., Beauducel A., Nessler D., Brocke B., Heilemann H., Kayser J. Is resting anterior EEG alpha asymmetry a trait marker for depression? Findings for healthy adults and clinically depressed patients. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;41(1):31–37. doi: 10.1159/000026630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deldin P.J., Chiu P. Cognitive restructuring and EEG in major depression. Biol. Psychol. 2005, Dec;70(3):141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deslandes A.C., de Moraes H., Pompeu F.A., Ribeiro P., Cagy M., Capitão C. Electroencephalographic frontal asymmetry and depressive symptoms in the elderly. Biol. Psychol. 2008, Dec;79(3):317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D.C.: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fingelkurts A.A., Fingelkurts A.A. Altered structure of dynamic electroencephalogram oscillatory pattern in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry. 2015, Jun 15;77(12):1050–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingelkurts A.A., Fingelkurts A.A., Rytsälä H., Suominen K., Isometsä E., Kähkönen S. Composition of brain oscillations in ongoing EEG during major depression disorder. Neurosci. Res. 2006, Oct;56(2):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold C., Fachner J., Erkkilä J. Validity and reliability of electroencephalographic frontal alpha asymmetry and frontal midline theta as biomarkers for depression. Scand. J. Psychol. 2013, Apr;54(2):118–126. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollan J.K., Hoxha D., Chihade D., Pflieger M.E., Rosebrock L., Cacioppo J. Frontal alpha EEG asymmetry before and after behavioral activation treatment for depression. Biol. Psychol. 2014, May;99:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon E., Palmer M., Cooper N. EEG alpha asymmetry in schizophrenia, depression, PTSD, panic disorder, ADHD and conduct disorder. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2010, Oct 1;41(4):178–183. doi: 10.1177/155005941004100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib I.H. EEG alpha asymmetry, depression, and cognitive functioning. Cogn. Emot. 1998;12(3):449–478. [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann D., Naumann E., Becker G., Maier S., Bartussek D. Frontal brain asymmetry and affective style: a conceptual replication. Psychophysiology. 1998, Jul;35(4):372–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E., Allen J.J. Behavioral activation sensitivity and resting frontal EEG asymmetry: covariation of putative indicators related to risk for mood disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1997, Feb;106(1):159–163. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi A., Pino L.J., Moffat G., Mathewson K.J., Aimone C., Bennett P.J. Characterizing population EEG dynamics throughout adulthood. ENeuro. 2016;3(6) doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0275-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques J.B., Davidson R.J. Left frontal hypoactivation in depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991;100(4):535–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworska N., Blier P., Fusee W., Knott V. Α power, α asymmetry and anterior cingulate cortex activity in depressed males and females. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2012, Nov;46(11):1483–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesulola E., Sharpley C.F., Bitsika V., Agnew L.L., Wilson P. Frontal alpha asymmetry as a pathway to behavioural withdrawal in depression: research findings and issues. Behav. Brain Res. 2015, Jun 5;292:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesulola E., Sharpley C.F., Agnew L.L. The effects of gender and depression severity on the association between alpha asymmetry and depression across four brain regions. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, Mar 15;321:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser A.K., Doppelmayr M., Iglseder B. Electroencephalogram alpha asymmetry in geriatric depression: valid or vanished? Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, Jul 15 doi: 10.1007/s00391-016-1108-z. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch J.D., Sander M.C., von Oertzen T., Brandmaier A.M., Werkle-Bergner M. Using within-subject pattern classification to understand lifespan age differences in oscillatory mechanisms of working memory selection and maintenance. NeuroImage. 2015, Sep;118:538–552. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser J., Tenke C.E. On the benefits of using surface Laplacian (current source density) methodology in electrophysiology. Int. J. Psychophysiol. Off. J. Int. Organ. Psychophysiol. 2015;97(3):171. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeser D., Karch S., Davis J.R., Surmeli T., Engelbregt H., Länger A. Changes of resting-state EEG and functional connectivity in the sensor and source space of patients with major depression. Klin. Neurophysiol. 2013;44(01):142. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley N.J., Hortensius R., Schutter D.J., Harmon-Jones E. The relationship of approach/avoidance motivation and asymmetric frontal cortical activity: a review of studies manipulating frontal asymmetry. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2017, Mar;10 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2017.03.001. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp A.H., Griffiths K., Felmingham K.L., Shankman S.A., Drinkenburg W.H.I.M., Arns M. Disorder specificity despite comorbidity: resting EEG alpha asymmetry in major depressive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychol. 2010;85(2):350–354. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentgen L.M., Tenke C.E., Pine D.S., Fong R., Klein R.G., Bruder G.E. Electroencephalographic asymmetries in adolescents with major depression: influence of comorbidity with anxiety disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2000;109(4):797–802. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Koretz D., Merikangas K.R. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003, Jun 18;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott V., Mahoney C., Kennedy S., Evans K. EEG power, frequency, asymmetry and coherence in male depression. Psychiatry Res. 2001, Apr 10;106(2):123–140. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(00)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Sarapas C., Shankman S.A. Anticipatory reward deficits in melancholia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2016, May 12;125(5):631–640. doi: 10.1037/abn0000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers C.D., Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006, Nov;3(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathersul D., Williams L.M., Hopkinson P.J., Kemp A.H. Investigating models of affect: relationships among EEG alpha asymmetry, depression, and anxiety. Emotion. 2008, Aug;8(4):560–572. doi: 10.1037/a0012811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslock R., Walden K., Harmon-Jones E. Asymmetrical frontal cortical activity associated with differential risk for mood and anxiety disorder symptoms: an rdoc perspective. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2015, Nov;98(2 Pt 2):249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten S.B., Williams J.V.A., Lavorato D.H., Bulloch A.G.M., Wiens K., Wang J. Why is major depression prevalence not changing? J. Affect Disord. 2016, Jan;190:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli D.A., Nitschke J.B., Oakes T.R., Hendrick A.M., Horras K.A., Larson C.L. Brain electrical tomography in depression: the importance of symptom severity, anxiety, and melancholic features. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002, Jul 15;52(2):73–85. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price G.W., Lee J.W., Garvey C., Gibson N. Appraisal of sessional EEG features as a correlate of clinical changes in an rtms treatment of depression. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2008, Jul;39(3):131–138. doi: 10.1177/155005940803900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C.R., Rennie C.J., Harris A.W.F., Kemp A.H. The impact of melancholia versus non-melancholia on resting-state, EEG alpha asymmetry: electrophysiological evidence for depression heterogeneity. Psychiatry Res. 2014, Jan;215:614–617. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quraan M.A., Protzner A.B., Daskalakis Z.J., Giacobbe P., Tang C.W., Kennedy S.H. EEG power asymmetry and functional connectivity as a marker of treatment effectiveness in DBS surgery for depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014, Apr;39(5):1270–1281. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid S.A., Duke L.M., Allen J.J. Resting frontal electroencephalographic asymmetry in depression: inconsistencies suggest the need to identify mediating factors. Psychophysiology. 1998, Jul;35(4):389–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M.S., Adams D.C., Gurevitch J. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 2000. MetaWin: Statistical Software for Meta-Analysis. Version 2.1. [Google Scholar]

- Saletu B., Brandstätter N., Metka M., Stamenkovic M., Anderer P., Semlitsch H.V. Hormonal, syndromal and EEG mapping studies in menopausal syndrome patients with and without depression as compared with controls. Maturitas. 1996, Feb;23(1):91–105. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00946-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer C.E., Davidson R.J., Saron C. Frontal and parietal electroencephalogram asymmetry in depressed and nondepressed subjects. Biol. Psychiatry. 1983, Jul;18(7):753–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrave R.A., Cooper N.R., Thomson R.H., Croft R.J., Sheppard D.M., Fitzgerald P.B. Individualized alpha activity and frontal asymmetry in major depression. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2011, Jan;42(1):45–52. doi: 10.1177/155005941104200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E.E., Reznik S.J., Stewart J.L., Allen J.J. Assessing and conceptualizing frontal EEG asymmetry: an updated primer on recording, processing, analyzing, and interpreting frontal alpha asymmetry. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2017, Jan;111:98–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J.L., Bismark A.W., Towers D.N., Coan J.A., Allen J.J. Resting frontal EEG asymmetry as an endophenotype for depression risk: sex-specific patterns of frontal brain asymmetry. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2010, Aug;119(3):502–512. doi: 10.1037/a0019196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J.L., Coan J.A., Towers D.N., Allen J.J. Resting and task-elicited prefrontal EEG alpha asymmetry in depression: support for the capability model. Psychophysiology. 2014, May;51(5):446–455. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibodeau R., Jorgensen R.S., Kim S. Depression, anxiety, and resting frontal EEG asymmetry: a meta-analytic review. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2006, Nov;115(4):715–729. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuga M., Fox N.A., Cohn J.F., George C.J., Levenstein R.M., Kovacs M. Long-term stability of frontal electroencephalographic asymmetry in adults with a history of depression and controls. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2006, Feb;59(2):107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M., Martinez J.H., Young D., Chelminski I., Dalrymple K. Severity classification on the Hamilton depression rating scale. J. Affect. Disord. 2013;150(2):384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material