Summary

Natural and drug rewards increase the motivational valence of stimuli in the environment through Pavlovian learning mechanisms, becoming conditioned stimuli that directly motivate behavior in the absence of an original unconditioned stimulus. While the hippocampus has received extensive attention for its role in learning and memory processes, less is known regarding its role in drug-reward associations. We used in vivo Ca2+ imaging in freely moving mice during the formation of nicotine preference behavior to examine the role of the dorsal-CA1 region of the hippocampus in encoding contextual reward-seeking behavior. We show the development of specific neuronal ensembles whose activity encodes nicotine-reward contextual memories and which are necessary for the expression of place preference. Our findings increase our understanding of CA1 hippocampal function in general, and as it relates to reward processing by identifying a critical role for CA1 neuronal ensembles in nicotine place preference.

Keywords: Nicotine, Dorsal CA1 hippocampus, In vivo Calcium imaging, Place Preference

Graphical Abstract

eTOC: Xia et al., find that nicotine contextual learning (place preference) recruits specific CA1 neuronal ensembles within drug-paired contexts and that these ensembles are also reactivated in drug-paired contexts in the absence of nicotine. These findings indicate that CA1 ensembles integrate nicotine-contextual information for subsequent cued-behavioral responses.

Introduction

Nicotine use through tobacco is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States (Lerman et al., 2014). Learned associations between environmental cues and the rewarding properties of nicotine are a major cause for the persistence of nicotine use and relapse among abstinent users (Lazev et al., 1999; De Biasi and Dani, 2011). Maladaptive memories between drug reward and contextual cues experienced during drug use are powerful and are a major cause of craving and relapse (Picciotto and Kenny, 2013; Fowler et al., 2011). Studying the contexts in which rewards have been experienced is paramount to understanding the basic neurobiology of learning, as well as how drugs such as nicotine “hijack” endogenous learning circuits to form long-lasting maladaptive changes that promote the risk of addiction (Napier et al., 2013; Dong and Nestler, 2014; Everitt and Robbins, 2016; Astur et al., 2016).

Although the hippocampus has been widely examined for its role in learning and memory processes, including the encoding of the memory for spatial locations (Tsien et al., 1996; Broussard et al., 2016), its role in coding contextually salient information specifically associated with reward and reward seeking behaviors has received much less attention. Place cells in the dorsal-CA1 region of the hippocampus are well known for their role in the cognitive representation of specific locations in space (Eichenbaum et al., 1999; Brun et al., 2002; Leutgeb et al., 2005). Reports have suggested a potential deficit in contextual associations resulting from dorsal-CA1 manipulations (Trouche et al., 2016; Meyers et al., 2003; Meyers et al., 2006; Ito et al., 2008). Recent findings implicate an increase in hippocampal/nucleus accumbens activity that occurs after cocaine-CPP expression due to strengthening of place cell activity during conditioning (Sjulson et al., 2017). These studies suggest that the CA1 region is an essential component of a neural circuit that mediates the formation of reward-associated contextual representations, yet direct evidence of CA1 activity in nicotine reward-context associations is absent as is visualization of neuronal ensemble recruitment over time in freely moving mice during Pavlovian conditioning and preference behavior.

Here, we determined that CA1 neuronal activity is necessary for both the acquisition and expression of nicotine-reward contextual associations. To dissect the specific changes in dorsal-CA1 hippocampal activity dynamics that occur during the acquisition and expression of these nicotine reward-contextual associations, we used in vivo real time Ca2+ imaging of CA1 pyramidal neurons expressing GCaMP6f during nicotine CPP in freely moving mice. We determined the role of dorsal-CA1 neuronal activity during nicotine CPP expression in response to the contextual information associated with the nicotine-reward as opposed to involvement in the subsequent instrumental or goal seeking component of reward-memory reactivation (Everitt and Robbins, 2016; Astur et al., 2016). These data demonstrate that CA1 neurons differentiate into ensembles associated with the transition into a reward-paired contextual memory, and provide evidence that nicotine engages unique CA1 neuronal ensembles to integrate highly salient reward information within spatial environments.

Results

Chemogenetic silencing of dorsal-CA1 neurons blocks nicotine-CPP acquisition and expression

We first determined whether CA1 neuronal activity is necessary for the acquisition and expression of nicotine-contextual associations. We used a chemogenetic approach combined with the classical Pavlovian model of CPP, commonly used to assess the rewarding properties of abused drugs. The CPP model has high utility and throughput for examining the underlying neural circuitry involved in the formation of drug-associated contextual memories (Tzschentke, 2007; Subramaniyan and Dani, 2015; Bruchas et al., 2011). During nicotine CPP training, mice injected with AAV5-CaMKIIα-hM4D(Gi)-mCitrine DREADD virus (hereafter referred to as ‘hM4D(Gi) mice’) (Roth, 2016; Lopez et al., 2016) or AAV5-CaMKII-mCitrine (hereafter referred to as ‘mCitrine control mice’) into the dorsal-CA1 region of the hippocampus (Figure 1A–C, Figure S2F) were administered the DREADD ligand CNO (1mg/kg, i.p) 30 minutes prior to each 20-minute nicotine conditioning session (Figure 1D) to silence activity of these cells during conditioning. Silencing CA1 neurons prior to nicotine conditioning significantly blocked the acquisition of a preference for the nicotine context (Figure 1E). To confirm the lack of an association with the nicotine-paired context, 24 hours later we tested for nicotine-primed CPP (Biala and Budzynska, 2006) and found that hM4D(Gi) mice also had lower nicotine primed CPP scores as compared to mCitrine control mice (Figure 1E). These data indicate that CA1 activity during nicotine-contextual conditioning is necessary for the formation of a nicotine-reward contextual association. Next, to determine whether CA1 neuronal activity is also necessary for the expression of a nicotine-contextual association, in a separate experiment, a new group of hM4D(Gi) mice were administered CNO 30 minutes prior to the test for CPP expression (20 minutes) (Figure 1I, day 24: post-test). Chemogenetic inhibition of CA1 neurons prior to CPP post-test, blocked the expression of nicotine CPP, establishing that CA1 activity is necessary for the expression of the nicotine-contextual reward memory (Figure 1J). However, when tested for CPP expression 24 hours later in the absence of CNO, hM4D(Gi) mice still showed a preference for the nicotine-paired side in response to a nicotine-priming injection (Figure 1J). These data suggest that although an association between nicotine reward experience and the nicotine-paired context had been made, that CA1 activity is also necessary for the expression of this association (Figure 1J). In both experiments, locomotor responses did not differ between groups during the post-test, nicotine-prime test or conditioning sessions (Figure 1F,G,H,L; Figure 1K,L) suggesting that these effects of CNO were not due to any aberrant effects on nicotine-induced activity or the animals ability to move around and explore the chambers during testing. Together, these data suggest that dorsal-CA1 activity is necessary for both the acquisition and expression of a nicotine-reward contextual memory.

Figure 1. Chemogenetic inhibition of dorsal-CA1 neurons blocks nicotine-CPP acquisition and expression.

(A) Diagram of bilateral AAV5-CaMKIIα-HA-hM4D(Gi)-IRES-mCitrine DREADD viral injections into the dorsal-CA1 region of the hippocampus (top). Confocal (10×) image of AAV5-CaMKIIa-HA-hM4D(Gi)-IRES-mCitrine DREADD expression in CA1 (bottom). Scale bar =250 microns. (B) Zoomed in confocal (10×) image of AAV5-CaMKIIa-HA-hM4D(Gi)-IRES-mCitrine DREADD expression (20× inset), and (C) AAV5-CaMKIIα-mCitrine (control virus) expression in the CA1 (20× inset), mCitrine (green), See also Figure S2F. (D) Timeline of behavioral testing for CPP acquisition experiment. (E) Activation of hM4D(Gi) DREADDs in the CA1 by CNO 30 minutes before each nicotine (PM) conditioning session attenuates the acquisition of nicotine CPP and nicotine-primed CPP (n=9 mCitrine mice (controls), n=13 hM4D(Gi) mice, Two-Way ANOVA, F(1,20)=23.31,p<0.05, bonferonni post hoc post-test (left two bars): *p<0.01, prime (right two bars): ***p<0.0001), (F) without changing locomotor responses during post testing (Two-Way ANOVA F(1,20)=0.052, p=0.82). (G) CNO before nicotine conditioning sessions does not change locomotor responses to nicotine (Two-way ANOVA, F(1,20)=0.24,p=0.63). (H) Representative behavior tracks from hM4D(Gi) and control mice during CPP post testing and nicotine prime test. (I) Timeline of behavioral testing for CPP expression experiment. (J) Activation of hM4D(Gi) DREADDs in the CA1 by CNO 30 minutes before the CPP post-test blocks nicotine CPP expression, but does not affect the expression of nicotine-primed CPP 24 hours later (n=11 mCitrine mice (controls), n=12 hM4D(Gi) mice, Two-way ANOVA, F(1,21)=10.63,p=0.004, bonferonni post hoc post-test (left two bars): p=0.02, prime (right two bars): p=0.44), (K) without changing locomotor response to during testing (Two-Way ANOVA, F(1,21)=3.26,p=0.78). (L) No difference in conditioning day locomotor behavior was seen between control and hM4D(Gi) mice used in the CPP expression experiment (Two-way ANOVA, F(1,21)=0.012,p=0.91). All data are presented as mean ± SEM.

In vivo Ca2+ imaging of dorsal-CA1 hippocampal neuronal activity during the acquisition of nicotine conditioned place preference

Next, to dissect the specific changes in dorsal-CA1 hippocampal activity dynamics that occur during the acquisition and expression of nicotine reward-contextual associations, we utilized in vivo real time Ca2+ imaging of pyramidal CA1 neurons during nicotine CPP in freely moving mice (Figure 2A–D, Video S1). A detachable mini-microscope was used to image fluorescent Ca2+ signals (AAV5-CaMKIIα-GcAMP6f) in dorsal-CA1 neurons during the nicotine-CPP protocol described in Figure 1 (Figure 2E). On day 1 of behavioral testing (Figure 2E, Pretest), we imaged dorsal-CA1 Ca2+ activity during the pre-test in which mice freely explored both chambers of the CPP apparatus. This was followed by Ca2+ imaging during 2 days of conditioning in which mice were injected with saline and confined to one side of the apparatus for 20 minutes in the AM, and at least 4 hours later injected with nicotine (0.5 mg/kg, s.c.) and confined to the opposite chamber for another 20-minute imaging session. On day 4 (Post-test), mice were again imaged while given free access to explore the entire CPP apparatus for 20 minutes to probe test for nicotine place preference as determined by the time they spent in the drug-paired chamber post-test minus pre-test (Figure 2F, Figure S1D). The following 3 groups of control mice were used: nicotine-paired/non-CPP expressing (Figure S1A), saline-only controls (Figure S1B) and nicotine-unpaired controls (Figure S1C). Since the rewarding effects of nicotine are subtle and can produce both a preference and aversion depending on individual variability between mice (Picciotto, 2003; Cunningham et al., 2006; Brielmaier et al., 2008), we were able to image and analyze data from 3 mice that did not develop a CPP for the nicotine-paired context (nicotine-paired/non-CPP expressing mice). These mice served as a valuable control group, which would have been less likely with a highly rewarding drug, such as cocaine. Saline-only controls were given saline in both AM and PM conditioning sessions (Figure S1B) and nicotine-unpaired controls received nicotine (PM) in both chambers on alternating days (Figure S1C). This control group was used to account for any potential nicotine-induced effects on Ca2+ activity unrelated to the contextual association. Calcium transient data from each behavioral session were processed to detect changes in activity and to track all labeled neurons during CPP behavior and importantly, analysis of all these data was performed blinded to treatment group. By generating a spatial neuronal map of all imaged neurons with their corresponding signal traces for each CPP test and conditioning session, we demonstrate successful tracking of over 90% of the total imaged neurons over the conditioning from all mice (mean=182 neurons per mouse in pre-test, mean=179 neurons per mouse in training sessions, mean=179 neurons per mouse in posttest, n>2700 neurons total from n=13 mice)

Figure 2. In vivo Ca2+ imaging of dorsal-CA1 hippocampal neuronal activity during the acquisition of nicotine conditioned place preference.

(A) Cartoon of virus injection (left) with 10× confocal image of AAV5-CaMKIIα-GCaMP6f expression in the CA1 HIP (middle) and cartoon of microendoscope on top of confocal image of CA1 region with GRIN lens implant (right), GCaMP6f (green), Nissl (blue). (B) Raw in vivo epifluorescence image of AAV5-CaMKIIα-GCaMP6f expression in the CA1 taken with mini-scope from (A) during CPP behavior. (C) Transformed image of (B) to show relative change in fluorescence (ΔF/F0). White arrows indicate cell bodies. (D) Photograph of mouse with mini-epifluorescence microscope for Ca2+ imaging during behavior.(E) CPP behavioral testing/Ca2+ imaging timeline and cartoon of CPP apparatus. See also Figure S1A–C. (F) Mice conditioned with nicotine (Nicotine-paired CPP expressing mice) had significantly higher CPP scores (time spent in the nicotine-paired side during post-test minus pre-test) than saline control mice (Unpaired t-test, n=6 per group, t(10)=3.72,p=0.004). See also Figure S1D. (G) Correlation between Ca2+ event frequency per cell during nicotine (PM) conditioning sessions and subsequent CPP scores in nicotine-paired mice (CPP expressing and non-CPP expressing, n=8, Pearson’s correlation coefficient r=0.74,p=0.03). See also Figure S1E–G. (H) Neuron map and pie chart indicating that >90% of imaged neurons were successfully tracked across all 6 behavior sessions (white cells). Blue cells indicate neurons missed during the pre-test and red cells indicate neurons missed during the post-test (<5%). (I) Representative Ca2+ temporal traces on corresponding neuron maps from 30 seconds of activity recorded during a saline-paired (AM) (left) and nicotine-paired (PM) (right) conditioning session. Purple traces represent neurons that only show Ca2+ activity during nicotine-paired sessions. Green traces indicate neurons that only show Ca2+ activity during the saline-paired session. Corresponding neuronal egg map labels neurons based on whether they displayed Ca2+ activity during the saline-paired session (green neurons), during the nicotine-paired session (purple neurons) or during both sessions (grey neurons). See also Figure S1H–K. (J) In CPP expressing mice, the frequency of Ca2+ activity (events/minute/cell) of neurons active during the nicotine-paired session is significantly greater than during the saline-paired session (Paired t-test, n=5 mice, t(4)=9.21,p=0.0008). (K) Saline-controls do not show a difference in Ca2+ frequency (events/minute/cell) between AM and PM conditioning sessions (Paired t-test, n=4 mice, t(3)=1.27,p=0.29). See also Figure S1L–M. (L) Normalized Ca2+ response intensity distribution for nicotine CPP-expressing mice showing the percentage of cells that have higher intensity in the nicotine-paired side compared to the saline-paired side (n=5 mice, Paired t-test, t(4)=5.44,p=0.01). (M) Normalized Ca2+ response intensity distribution for saline control mice showing the percentage of cells have higher intensity in the PM side compared to the AM side (n=4 mice, Paired t-test, t(3)=0.13,p=0.90). See also Figure S1N–O. All scale bars equal 100 microns. Data are mean ±SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

With the data collected during nicotine-conditioning sessions, we defined neuronal ensembles based on whether they were active during the saline (AM) or nicotine (PM) conditioning sessions (Figure 2I, Figure S1H–K). Cells that responded during the nicotine-session had significantly higher Ca2+ frequencies than cells active during saline-conditioning sessions. Interestingly, this effect was only seen in mice that subsequently expressed nicotine CPP (Figure 2F,J; Figure S1H, CPP-expressing mice). As expected, saline control mice showed no preference for either side of the conditioning apparatus (Figure 2F) and no significant difference between Ca2+ transient frequency during AM and PM conditioning sessions was observed (Figure 2K; Figure S1I). This effect was also absent in nicotine-paired mice that did not express a preference for the nicotine context (non-CPP expressing, Figure S1D,J,L) or the nicotine-unpaired control group (Figure S1D, K,M) indicating that the observed effect was not solely due to nicotine-induced Ca2+ activity during conditioning. Specifically, these data suggest that dorsal-CA1 pyramidal neurons are recruited during nicotine-conditioning (during the reward pairing) and have a higher frequency of activity as compared with that from the saline conditioning session (non-reward pairing), indicating a role for nicotine reward-induced neuronal activity within dorsal-CA1 in the acquisition of contextual associations. We also found that the frequency of Ca2+ activity during nicotine (PM) conditioning sessions was positively correlated to subsequent preference scores in nicotine-paired mice (CPP and non-CPP expressing groups), but not in saline control group or for any other control group during their saline (AM) conditioning session (Figure 2G; Figure S1E–G). This finding suggests that increases in nicotine-induced Ca2+ activity in the dorsal-CA1 are related to the rewarding effects of nicotine in addition to subsequent nicotine-seeking behaviors and contextual-associations, since lower CPP scores were associated with less Ca2+ activity during nicotine-conditioning. Considering that Ca2+ transient intensity (∆F/F0 amplitude) may also reflect the total number of actual action potentials (Betley et al., 2015; Theis et al., 2016) we used the intensity of all events to develop an intensity distribution of Ca2+ transient activity for each group of mice (Figure 2L–M, Figure S1N–O). The Ca2+ transient intensity was normalized to the maximum intensity from each session and evenly divided into 10 magnitudes ranging from 0–1. We then calculated the mean (and SD) Ca2+ transient event intensity for each mouse. Events with Ca2+ transient intensities greater than the mean (0.22±0.14) were defined as “high responding events.” In CPP expressing mice (Figure 2L), a significantly larger percentage of neurons displayed high responding events during nicotine conditioning sessions, compared with the saline-paired conditioning session (Figure 2L). In addition, we did not detect a significant shift in the transient intensity distribution between AM and PM sessions in any of the control groups (Figure 2M, Figure S1N–O). Together, these data suggest that nicotine pairing impacts both the frequency and intensity of dorsal-CA1 pyramidal neuron Ca2+ activity during nicotine conditioning which corresponds to the magnitude of the nicotine-reward experience as assayed here via expression nicotine CPP behavior.

In vivo Ca2+ imaging of CA1 hippocampal neuronal activity during the acquisition and expression of an operant reward task

To investigate the specificity of dorsal-CA1 neural activity to spatial representation of contextual-nicotine-reward associations, we also imaged Ca2+ transients in an operant reward-learning task in mice confined to a single context with a cue paired to the delivery of a natural reward. We imaged dorsal-CA1 Ca2+ activity while mice were trained to nosepoke for a sucrose reward via a lickometer (Figure 3A–B). By day 5 of Fixed Ratio 1 (FR1) training (day 37), all mice had learned that an active nosepoke resulted in a sucrose reward and poked the active nosepoke significantly more than during the first day of training (day 33) (Figure 3C–E). We then calculated the Ca2+ event frequency (Figure 3G–I), and intensity distribution (Figure 3J–L) for neurons before and after each active nosepoke on the day before and after the FR1 task was learned. We used a criteria of 3:1 active to inactive nosepokes to confirm learning, as previously described (Haluk and Wickman, 2010). No significant changes between Ca2+ transient activity before nose poke and after nosepoke were seen after the operant task was acquired compared to the day before acquisition (Figure 3F–L). Ca2+ activity did not change across the course of operant training and did not correspond to the presentation of the cue that signified a sucrose reward at any point during training (Figure 3F). There were also no significant changes in Ca2+ transient activity before and after the consumption of the sucrose reward (Figure 3I,L). We selected groups of neurons whose total ca2+ activity increased during licking behavior, nosepoke behavior, or both and found no significant difference between the numbers of neurons in each group (Figure 3M). Therefore, although some groups of neurons do respond selectively to occurrences of these behaviors, there is no group of neurons that consistently respond to the same event (Figure 3N–P). These data further indicate the specificity of CA1 ensemble activity to contextual-reward associations and not solely as responding to a reward presentation.

Figure 3. In vivo Ca2+ imaging of CA1 hippocampal neuronal activity during the acquisition and expression of an operant reward task.

(A) Timeline of imaging and Fixed Ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of operant lickometer training and illustration of mouse in operant chamber. (B) Representative neuron map and temporal traces for 10 neurons during a 1 hour FR1 training session. Corresponding colors represent neurons and traces. (C) Representative behavior from one mouse during the first day of FR1 training (day 33), no difference is seen between the number of active and inactive nosepokes during the first training session. (D–E) By day 37 (FR1 training day 5), mice poke the active nosepoke significantly more than the inactive nosepoke (F) Representative raster and histogram showing licking behavior aligned with Ca2+ events during the 5 seconds before and 20 seconds after each cue presentation. (G–I) Neurons are distributed into a two-dimensional field. The x-axis shows Ca2+ event frequency after each active nosepoke and the y-axis shows Ca2+ event frequency before each active nosepoke or reward (I). (J–L) Normalized Ca2+ response intensity distribution before and after each active nosepoke, before FR1 criteria met (day 33) (J) and after (day 37) (K) and before and after a reward (L). (M) Cellular spatial map and corresponding bar graph categorizing neurons based on whether they displayed Ca2+ activity for more than 20% of the total Ca2+ activity of that neuron time locked to one of two actions: An active nosepoke (blue), or during the first sucrose lick following sucrose delivery (green). Pink represents neurons that were active during both actions. Bar graph shows the number of neurons (%) in each group. No statistically significant differences were seen. (N) Normalized Ca2+ activity raster showing Ca2+ activity for neurons active during both behaviors (M, Pink neurons), during each active nosepoke (top) and during the first lick after sucrose delivery (bottom). See also Figure S2A–E. (O) Normalized Ca2+ activity raster plot showing Ca2+ activity for neurons active during each active nosepoke (M, Blue neurons). (P) Normalized Ca2+ activity raster plot showing Ca2+ activity for neurons active during the first lick after sucrose delivery (M, green neurons). Note: there is a brief period of inhibition in this group just before the onset of the first lick. All traces are mean with SD.

To further extend our Ca2+ imaging results and to determine that these neurons do not play a role in the expression of an operant learning, we trained CA1-injected hM4D(Gi) mice in the same operant task, (Figure S2A). In contrast to our reward-context pairing results, when CNO was administered 30 minutes prior to a previously learned FR1 operant training session (or 24 hours later during another training session in the absence of CNO) the ability to perform the task was unaffected (Figure S2B). Furthermore, in a separate group of CA1-hM4D(Gi) mice, CNO did not affect the ability to learn when the operant schedule was changed from FR1 to fixed ratio 3 (FR3) which requires more effort (Figure S2C–E). Together these results, importantly suggest that specific dorsal-CA1 neuronal ensembles like those recruited during CPP are not likely recruited during the development non-contextual reward pairings we tested here.

Visualization of dorsal-CA1 Hippocampal neuronal activity during the expression of nicotine CPP

To further examine the role of CA1 neurons in nicotine CPP, we analyzed Ca2+ activity from all cells in relation to the spatial location in which they responded, to determine a role, if any, for CA1 place cells in encoding a nicotine-contextual reward association (Figure 4A–D). Due to the increased time spent in the nicotine side (Figure 2F), CPP expressing mice had a higher total neural activity in nicotine paired side in post-test (Figure 2J). In order to examine the linearity/non-linearity association between time spend in particular region and total Ca2+ activity in this region, we calculated the accumulated time and accumulated Ca2+ activity in each 3*3cm2 square region for each side in both pretest and posttest (Figure 4E,F). A 2-degree polynomial regression curve was fitted for each group of data. We found that CPP-expressing mice had the most linear-like association between time and activity in the nicotine paired side during the posttest and had the highest Pearson correlation (Table 2). This result suggests that in CPP expressing mice, there is a large association between time spent in a particular region in the nicotine-paired side during the post-test and implies an enhanced time and field logged place cell activity during the post-test. Consistent with previous imaging studies (Ziv et al., 2013), we found that about 20% of the CA1 neurons we imaged could be classified as place cells (Figure 4H,I). These were cells whose 80% response was associated with one specific location (25cm2) within the CPP chamber. Our results were also consistent with Ziv et al., (2013) in which a large percentage of neurons were found not to overlap when comparing the place code ensembles from two sessions when a mouse is placed in a familiar arena. By examining all place cells and their mapped field during the pretest and posttest, we also found that some place cells mapped to a different side in posttest after training instead of maintain responding for the same spatial location in the same side during pretest (Figure 4H), while some place cells remain responding to the same side (Figure 4I). However, we show that CPP expressing mice displayed a significantly higher percentage of place cells that changed map fields and mapped onto the nicotine-paired side than any other control group (Figure 4G).

Figure 4. Total Ca2+ activity of all imaged CA1 cells mapped onto spatial locations within the CPP apparatus together with “Place Cell” analysis.

(A–D) Gaussian-smoothed (σ=3.5cm) heat maps represent the total normalized Ca2+ transient activity (corrected by time on each pixel) for all cells corresponding to the location of the mouse within the CPP chamber during the pre-test and post-test in (A) CPP expressing mice, (B) saline controls, (C) non-CPP expressing, and (D) nicotine unpaired control mice. (E–F) Accumulated Ca2+ activity is plotted versus accumulated times for each 3cm2 region in each side of CPP chamber for all mice by different colors in CPP expressing group (E) and saline group (F). Data from CPP-expressing mice in nicotine side during posttest (purple) is fitted with a linear polynomial regression curve with corresponding color. (G) Average percentage of place cells remapped from pretest to post-test (25cm2). CPP-expressing mice had a higher percentage of consistent place cells (with saline controls: Paired t-test, t(5)=6.871,p=0.0010; with non-CPP-expressing: Paired t-test, t(5)=6.165,p=0.0016; with nicotine-unpaired: Paired t-test, t(5)=6.224,p=0.0016). (H) Place cell analysis showed that of the cells that responded to a specific location in the saline-paired side during the pre-test in Gaussian-smoothed (σ=3.5cm) density maps, were remapped after conditioning to encode a different spatial location in nicotine paired side during post-test (Representative cells 1–4). Red dots mark its position during Ca2+ events. (I) Some cells maintained place cell activity of their location during the pre-test across all testing sessions (Representative cells 5–8). All scale bars equal 10cm

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients between Ca2+ activity and time spent in the nicotine-paired side during the Posttest

| CPP expressing | Saline-only | Non-CPP expressing | Nicotine- Unpaired | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | ||||

| Nic/AM Side | 0.829 | 0.873 | 0.874 | 0.735 |

| Sal/PM Side | 0.859 | 0.924 | 0.869 | 0.774 |

| Post-Test | ||||

| Nic/AM Side | 0.904 | 0.762 | 0.792 | 0.774 |

| Sal/PM Side | 0.752 | 0.774 | 0.647 | 0.717 |

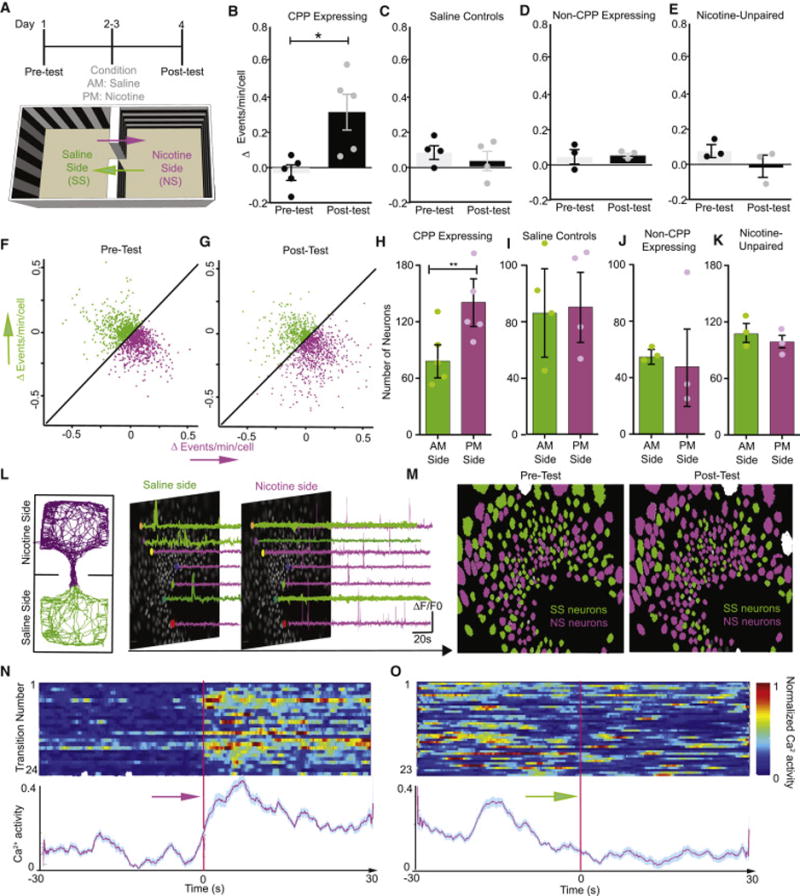

Next, to isolate the dynamic role of dorsal-CA1 nicotine reward-paired ensemble activity during the expression of a nicotine-CPP, we compared Ca2+ transient activity imaged prior to conditioning, during the drug-free pre-test (Figure 5A: Pre-test, day 1) to Ca2+ activity after nicotine-conditioning, during the drug-free preference test (Figure 5A: Post-test, day 4). We analyzed Ca2+ activity for each neuron as the mouse freely explored the CPP chambers according to whether activity occurred during one of two transition events defined by the direction of the mouse’s movement and location during nicotine CPP expression (Figure 5A, Video S2). The two transition events were defined as either ‘nicotine-paired transitions’ (occurring 30 seconds before and after the mouse entered the nicotine-paired side) or ‘saline-paired transitions’ (occurring 30 seconds before and after the mouse entered the saline-paired side). We then determined whether Ca2+ transient frequency was differentially modulated during each transition over the course of the pre-and post-tests. Thus, for each imaged mouse, we calculated the change in frequency as the frequency of Ca2+ transients occurring during nicotine-paired transitions minus the frequency of Ca2+ transients occurring during saline-paired transitions for both the pre-and post-tests. Interestingly, we found that during the post-test, the change in frequency of Ca2+ activity was larger in CPP-expressing mice than the activity of the same population of neurons during the pre-test (Figure 5B). We further defined two subcategories of neurons based on their transition-dependent changes in Ca2+ transient frequency (Figure 5F–G, Figure S3A–C). A larger number of neurons with higher changes in Ca2+ event frequency occurred during ‘nicotine-paired transitions’ compared to those same neuron’s Ca2+ activity during the pre-test (Figure 5F–G). In contrast, no differences in the change in Ca2+ frequency were observed in groups of control mice from pre-test to post-test (Figure 5C–E). During the pre-test, there was a relatively equal number of neurons responding during transitions from either side (Figure 5 H–M). However, during the post-test in CPP-expressing mice, a larger number of neurons that were recruited with higher activity during ‘nicotine-paired transitions’ compared to ‘saline-paired transitions’ (Figure 5 H–M). No significant difference in the number of neurons recruited during either transition event was observed in the control groups (Figure 5 I–K). In CPP-expressing mice, this same ensemble of ‘nicotine-paired transition’ neurons showed a marked increase in activity upon entry into the nicotine-paired side (Figure 5N) that then decreased during the transition into the ‘saline-paired’ side (Figure 5O). Furthermore, when examining the total population of neurons in CPP-expressing mice, the Ca2+ transient response during nicotine-paired transitions was increased (Figure S3D), while all other control groups did not show any change in total Ca2+ events during side transitions (Figure S3E–G). Additionally, we found that only in CPP-expressing mice, more neurons displayed higher intensity Ca2+ responses in the nicotine-paired side compared to the saline-paired side during the post-test (Figure S4A, right panel); whereas, no changes were found in Ca2+ intensity during the pre-test (Figure S4A, left panel), or in any of the control groups during either their pre-or post-tests (Figure S4B–D).

Figure 5. In vivo Ca2+ imaging of dorsal-CA1 Hippocampal neuronal activity during the expression of nicotine conditioned place preference.

(A) Timeline of CPP behavior and cartoon of CPP apparatus with arrows representing side transitions during the pre-test and post-test (Day 1 and Day 4). Purple arrows represent ‘nicotine-paired transitions’ from the saline-paired side to the nicotine-paired side (30 seconds before and after the mouse enters the nicotine-paired side). Green arrows represent ‘saline-paired transitions’ from the nicotine-paired side to saline-paired side (30 seconds before and after the mouse enters the saline-paired side). (B) CPP-expressing mice show a significantly larger change in frequency of Ca2+ activity (events/minute/cell) during nicotine-paired transitions during the post-test than was seen prior to conditioning during the pre-test (Paired t-test, n=5 mice, t(4)=2.84,p=0.04). C–E. The frequency of Ca2+ activity did not change during ‘saline-paired’ or ‘nicotine-paired’ transition events in (C) saline control mice (n=4 mice, Paired t-test t(3)=0.56,p=0.62), (D) non-CPP expressing mice (n=3 mice, Paired t-test t(2)=0.15,p=0.89), or (E) nicotine-unpaired mice (n=3 mice, Paired t-test t(2)=0.148,p= 0.89). (F–G) Neurons (n=1313 neurons, 5 mice) activated during nicotine-paired and saline-paired transitions the (F) pre-test and (G) post-test displayed in a 2-dimensional field where the x-axis represents the change in Ca2+ frequency during nicotine-paired transitions and the y-axis represents the change in Ca2+ frequency during saline-paired transitions. Purple points represent neurons with a higher frequency of Ca2+ transients (events/min/cell) during nicotine-paired transitions. Green points represent neurons with a higher frequency of Ca2+ transients during saline-paired transitions. See also Figure S3A–C. (H) CPP expressing mice have significantly more nicotine-paired neurons than saline-paired neurons (n=5 mice, paired t-test, t(4)=5.32,p=0.006). (I–K) Control groups show no difference in the number of neurons paired with either transition context: (I) saline controls (n=4, Paired t-test, t(3)=0.05,p=0.97), (J) non-CPP expressing (n=3, Paired t-test, t(2)=0.26,p=0.83), or (K) nicotine-unpaired controls (n=3, Paired t-test, t(2)=0.55,p=0.64). (L) Representative locomotor track from a nicotine CPP-expressing mouse during the CPP post-test and corresponding traces from neurons with higher Ca2+ activity during nicotine-paired transitions (purple traces) and neurons with higher activity during saline-paired transitions (green traces) displayed on egg maps. (M) Left panel: Representative neuron egg map from the pre-test showing neurons with higher frequencies of Ca2+ transients during either nicotine-paired (purple) or saline-paired (green) transitions. Right panel: Representative neuron egg map from a nicotine CPP-expressing mouse during the post-test (i.e. during CPP expression). More neurons have higher frequencies of Ca2+ transients during nicotine-paired transitions than during saline-paired transitions (n=701 nicotine-paired neurons (purple) and 419 saline-paired (green) neurons). (N–O) Raster represents total Ca2+ responses in CPP-expressing mice during nicotine-paired transitions and (O) during saline-paired transitions during the post-test. Each row represents one transition (top). Red line indicates actual time of side entry. The corresponding aligned trace represents the total normalized Ca2+ activity during each transition. See also Figure S3A–G and Figure 4A–E.

Using a complementary approach to thoroughly examine the formation of nicotine-dependent ensembles over time, a vector analysis was applied to these data and the similarity measure (the angle between vectors) was calculated (Bartho et al., 2009; Schoenbaum and Eichenbaum, 1995). The angle between nicotine-side to saline-side transition events for nicotine-paired neurons during the post-test was significantly larger compared to the angle observed between saline-side to nicotine-side transition events (Figure S4E–F). In control mice (saline controls, CPP non-expressing and nicotine-unpaired), the vector of all neurons during these transition events was calculated and no significant bi-directional difference between events was observed (Figure S4G–I). These data demonstrate that CA1 neurons differentiate into ensembles associated with the transition into a reward-paired context.

Discussion

We report that dorsal CA1 neuronal activity is necessary for both acquisition and expression of a nicotine CPP, but is not necessarily required for learning simple operant-based reward tasks (sucrose self-administration). Furthermore, these responses are robustly retained because in a subsequent nicotine-primed CPP reinstatement test, in the drug-paired context in the absence of silencing, mice can only reattribute a drug-paired context to express a CPP when the silencing occurred after the acquisition of the association. These results are similar to that observed by Trouche et al., (2016) in which mice no longer showed a CPP for a cocaine prime after photo-inhibition of dorsal CA1 neurons previously activated in the cocaine-paired context. Here we extended these findings using in vivo Ca2+ imaging in freely moving mice during nicotine CPP to visualize the real-time patterns of neuronal activity associated with nicotine preference and have identified a critical role for recruitment of dorsal-CA1 ensembles in nicotine-contextual associations. We report that dorsal-CA1 Ca2+ transient activity is tightly locked to subsequent nicotine-reward seeking behavior (Fig. 5) and is increased when an animal encounters related contextual cues. This may be the result of recall of the reward-context association or being in a context that has been previously associated with reward. We also found that this increased Ca2+ activity is more selective to Pavlovian reward-based contextual tasks as compared to specific operant-based rewards. This difference between CA1 neuron activity during the operant task as compared to CPP training is likely due to the non-hippocampal-dependent nature of the operant task, however other tasks and measures of operant responding and the CA1 are warranted in future studies. It is also plausible that any differences we see in CA1 activity could be due to the lack of a drug reward in the operant task, or in the differences between the contingent and non-contingent reward delivery. Nevertheless, these results suggest that dorsal-CA1 ensembles specifically encode nicotime-associated spatial cues related to contextual information. We report here that specific neuronal ensembles within the CA1 are recruited by nicotine-reward contextual pairings, and that their activity is necessary for the expression of this behavior suggesting that nicotine engages and potentiates CA1 activity to inform subsequent cued contextual behaviors.

By employing in vivo calcium imaging approaches with mini-scopes and GRIN lens implants in non-head fixed freely moving mice, we demonstrated successful tracking of over 90% of dorsal CA1 hippocampal neurons during six independent behavioral testing sessions. Computational work using a modified PCA/ICA analysis (Mukamel et al., 2009; Ziv et., 2013), with motion correction was reliable in our case due to the high number of GCaMP+ cells we could record in each session (100–300), and the reliable single photon resolution we obtained in most of our GRIN lens implanted mice. This newer methodology allowed us to define and record discrete neuronal ensembles during a complex behavioral assay such as nicotine place preference. The nicotine place preference behavioral approach is notoriously difficult, let alone with in vivo extracellular recordings, and thus information about how contextual cue and neuronal ensemble codes within the hippocampus are generated by nicotine-pairings have been previously limited (De Biasi and Dani, 2011; Penton et al., 2011). Here we show that mice tolerate the mini-scope well throughout conditioned place preference, as well as an operant-based behavioral task, and that one can stably record Ca2+ transient activity over the course of these types of more complex learned behaviors. This technical feat came with significant challenges, and still has its certain limitations. For one, tracking neurons reliably over the course of six-independent training sessions while measuring their Ca2+ transient activity proved difficult, however by using the same microscope for each individual animal and maintaining focusing specs (Resendez et al., 2016), we could obtain high resolution maps of each neuron’s activity in space facilitating robust detection of Ca2+ transients in each behavioral training session (Videos S1 and S2). This methodology also allowed us to visualize the developing potentiation of ensemble activity within dorsal CA1 as the nicotine CPP behavior transitioned from no initial preference (Fig. 2) all the way towards the expression of a place preference in each individual animal (Fig. 5). Furthermore, we examined dorsal CA1 neuronal ensembles in several control groups, including saline-saline (AM and PM pairings), nicotine-nicotine, and in saline-nicotine paired animals that failed to show a nicotine place preference. These experiments, definitively reveal specificity of a nicotine-paired CA1 ensemble that predicts and is active during CPP expression. A question remains regarding how stable these recruited ensembles within the dorsal CA1 are following expression of a nicotine CPP. Given that we can challenge a mouse with a priming dose of nicotine (Fig. 1), after having silenced CA1 neurons during CPP expression, and then reactivate this expression of a nicotine preference suggests that potentiated CA1 neuronal ensembles due to the nicotine pairing are indeed retained in subsequent trials. However, this hypothesis will require further examination with additional imaging cohorts.

CPP is a widely used behavioral measure that models the rewarding effects of drugs and contextual stimuli that occur in nicotine addicts (Astur et al., 2016; Napier et al., 2013). The data presented here together with previous findings have implicated hippocampal glutamatergic transmission in drugs of abuse that induce place preference (Portugal et al., 2014; Bossert et al., 2011; Zarrindast et al., 2007; LaLumiere and Kalivas, 2008; Zhou and Kalivas, 2008; Knackstedt and Kalivas, 2009; Xia et al., 2011). However, our results suggest that dorsal CA1 specific ensembles are crucial for the formation and maintenance of context-dependent associative behaviors. These data further support that the nicotine-context potentiated CA1 ensembles are engaged only during the pairing of salient reward stimuli with specific contextual information and are likely due to the operant task being non-hippocampal dependent. Furthermore, while several studies have implicated CA1 neurons in coding place information (Eichenbaum et al., 1999; Brun et al., 2002; Leutgeb et al., 2005; Hok et al., 2007), there are no previous reports that have visualized a recruitment of new ensembles by drug-context pairings during the development (training) of the actual Pavlovian behavior. While there is an established role for dorsal CA1 in place coding, our results here show that the activity of these neurons is further modulated by drug rewards when they are paired with discrete contexts or goal oriented behaviors as previously shown (Hollup et al., 2001; Dupret et al., 2010). Our data suggest that the drug-reward (nicotine in this case) pairing acts to engage the CA1 populations in a unique manner such that their activity is gated during both the training and CPP expression.

Taken together, our data provide unique evidence for a key role of the dorsal-CA1 hippocampus in nicotine reward-contextual associations and establish a relationship between nicotine preference behavior and neuronal network activity of the dorsal CA1 of hippocampus. The development and increase in activity of neuronal ensembles during the acquisition of contextual memories is a probable mechanism involved with organizing the large number of associative memories acquired over the course of an animal’s lifetime. Our results suggest a role for increased CA1 ensemble activity in maladaptive reward-contextual memories responsible for the persistence of drug-seeking in nicotine addiction. Here we provide evidence for the learning and memory hypothesis of addiction (Dong and Nestler, 2014; Everitt and Robbins, 2016) by observing the dynamic neuronal changes associated with normal learning and memory processes during the critical developmental phases of nicotine-contextual associations.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Male WT C57BL/6 mice maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 7am) were used for all experiments, which took place during the light cycle. Mice had free access to food and water for CPP experiments, but were food-restricted to 90% of their original body weight prior to operant training. All mice weighed 25–35g at the start of CPP behavioral testing (See Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Viral injection stereotaxic surgery was performed on 6-week-old mice to ensure appropriate age at the time of CPP testing. Mice were housed 3–5 per cage until GRIN lens implantation surgery after which mice (7–8weeks old) were individually housed to avoid damage to lens and head cap. Mice were maintained in a holding room adjacent to the behavioral testing room. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University in St. Louis and were in accordance with NIH standards.

Drug Administration

(−)- Nicotine hydrogen tartrate salt (Sigma, N5260) (0.5mg/kg, corrected for the weight of the tartrate salt) was suspended in saline and subcutaneously (s.c.) administered. Clozapine N-Oxide (CNO) (1mg/kg i.p.)(Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY; BML-N5105-0025) was made in 0.5% DMSO in saline (Jennings et al., 2015; Nygard et al. 2016).

In vivo Ca2+ imaging and data analysis

Ethovision behavior tracking software (Noldus) (used to record and analyze CPP behavior), was programmed to simultaneously trigger the onset behavioral tracking and the beginning of the imaging session (Ethovision was used to ‘turn on’ the mini-scope LED and camera so that behavior and Ca2+ imaging sessions were recorded in sync). Using nVista acquisition software (Inscopix), images were acquired at 20 frames per second. Ethovision was also programed to send TTL pulses (recorded in nVista as GPIO files) that provided time stamps corresponding to the location of the mouse in the CPP apparatus (Jennings et al., 2015). Mosaic™ (Inscopix) was used to preprocess Ca2+ data from each behavior/imaging session as previously described (Ziv et al., 2013; Resendez et al., 2016; Jennings et al., 2015; Rubin et al., 2015). Briefly, data were de-noised and motion correction applied. After preprocessing, single neuron activity was separated by PCA/ICA (Mukamel et al., 2009) in Mosaic™ and sorted manually. Down-sampling data by 2 points in the temporal dimension and 6 points in the spatial dimension, resulted in one dataset for single neuron spatial filters and another dataset set for single neuron time courses. The time course dataset was then processed with the spike detection algorithm built-into Mosaic™ software. Custom Matlab scripts were developed and used to further analyze these data.

Statistical Analysis

Statistically significant differences were determined at p<0.05, using Two-Way ANOVAs or paired t-tests where appropriate. All statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism v7.

Supplementary Material

Video S1. Ca2+ imaging and detection of transients during place preference behavior, Related to Figure 2,4,5.

Left panel: ∆F/F0 video recording during CPP test in freely moving mice. Six neurons have been randomly selected and outlined in different colors.

Right panel: Time traces of Ca2+ transients for each neuron outlined in the left panel are displayed in corresponding colors.

Video S2. Video S2. Tracking Ca2+ transient activity during conditioned place preference behavior, Related to Figure 2,4,5.

Top left panel: Video (40× normal speed) of a freely-moving mouse with implanted GRIN lens and mini-endoscope during a CPP test.

Bottom left panel: real time dorsal-CA1 Ca2+ transient recording during CPP test.

Top right panel: Heat map of Ca2+ transients derived from events detected in bottom left panel. Video is rebuilt using PCA/ICA and event detection analyses.

Bottom right panel: Cumulative map displaying cell registration during CPP test. Individual white ovals indicate individual cells detected from heat map analysis in top right panel.

Table 1.

Average number of dorsal CA1 cells imaged during each behavioral CPP testing session.

| Pre-test | Nicotine Conditioning | Post-test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | |||

| CPP expressing | 211.6 (± 87.45) | 206.6 (± 77.63) | 206.8 (± 75.79) |

| Saline-only | 164.5 (± 50.51) | 158.1 (± 49.12) | 158.5 (± 47.70) |

| Non-CPP expressing | 108.0 (± 37.24) | 108.1 (± 37.28) | 109.3 (± 36.61) |

| Nicotine Unpaired | 177.0(± 11.66) | 179.5 (± 12.01) | 180.5 (± 10.71) |

Highlights.

Dorsal-CA1 neuronal activity is necessary for nicotine place preference.

Unique CA1 ensembles are recruited during reward-paired contextual conditioning.

Discrete CA1 neuronal ensembles are reactivated only by nicotine-paired contexts.

CA1 ensembles develop temporally to distinguish reward-context information.

Acknowledgments

R01DA033396 (M.R.B.), and T32DA007261-22 (S.K.N.) from NIDA. DECODE: Inscopix (M.R.B.). We thank the viral core of Penn. We thank Jones Parker (Stanford, Schnitzer lab), G. Stuber (UNC), and Mazen Kheibeck (UCSF) for helpful technical advice. We thank Skylar M. Spangler and Daniel Castro for help editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: L.X. and S.K.N. designed studies, performed research, analyzed data, wrote the paper and contributed equally to this work. G.G.S. and N.J.H. performed behavioral experiments and helped process data. M.R.B. Designed studies, provided resources, and wrote the paper.

References

- Astur RS, Palmisano AN, Carew AW, Deaton BE, Kuhney FS, Niezrecki RN, Hudd EC, Mendicino KL, Ritter CJ. Conditioned place preferences in humans using secondary reinforcers. Behav Brain Res. 2016;297:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartho P, Curto C, Luczak A, Marguet SL, Harris KD. Population coding of tone stimuli in auditory cortex: dynamic rate vector analysis. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1767–1778. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betley JN, Xu S, Cao ZFH, Gong R, Magnus CJ, Yu Y, Sternson SM. Neurons for hunger and thirst transmit a negative-valence teaching signal. Nature. 2015;521:180–185. doi: 10.1038/nature14416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biala G, Budzynska B. Reinstatement of nicotine-conditioned place preference by drug priming: Effects of calcium channel antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;537:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert JM, Stern AL, Theberge FR, Cifani C, Koya E, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Ventral medial prefrontal cortex neuronal ensembles mediate context-induced relapse to heroin. Nat Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nn.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brielmaier JM, McDonald CG, Smith RF. Nicotine place preference in a biased conditioned place preference design. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussard JI, Yang K, Levine AT, Tsetsenis T, Jenson D, Cao F, Garcia I, Arenkiel BR, Zhou FM, De Biasi M, et al. Dopamine Regulates Aversive Contextual Learning and Associated In Vivo Synaptic Plasticity in the Hippocampus. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1930–1939. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchas MR, Schindler AG, Shankar H, Messinger DI, Miyatake M, Land BB, Lemos JC, Hagan CE, Neumaier JF, Quintana A, et al. Selective p38α MAPK deletion in serotonergic neurons produces stress resilience in models of depression and addiction. Neuron. 2011a;71:498–511. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun VH, Otnass MK, Molden S, Steffenach HA, Witter MP, Moser MB, Moser EI. Place cells and place recognition maintained by direct entorhinal-hippocampal circuitry. Science. 2002;296:2243–2246. doi: 10.1126/science.1071089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzulino AS, Martinez R, Tomm NK, Denny CA. Improved specificity of hippocampal memory trace labeling: ENGRAMS IN ArcCreERT2 MICE. Hippocampus. 2016;26:752–762. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and aversion in mice. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1662–1670. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Biasi M, Dani JA. Reward, addiction, withdrawal to nicotine. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:105–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Nestler EJ. The neural rejuvenation hypothesis of cocaine addiction. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:374–383. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupret D, O’Neill J, Pleydell-Bouverie B, Csicsvari J. The reorganization and reactivation of hippocampal maps predict spatial memory performance. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:995–1002. doi: 10.1038/nn.2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Dudchenko P, Wood E, Shapiro M, Tanila H. The Hippocampus, Memory, and Place Cells. Neuron. 1999;23:209–226. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Drug Addiction: Updating Actions to Habits to Compulsions Ten Years On. Annu Rev Psychol. 2016;67:23–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CD, Lu Q, Johnson PM, Marks MJ, Kenny PJ. Habenular α5 nicotinic receptor subunit signalling controls nicotine intake. Nature. 2011;471:597–601. doi: 10.1038/nature09797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haluk DM, Wickman K. Evaluation of study design variables and their impact on food-maintained operant responding in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2010;207:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hok V, Lenck-Santini PP, Roux S, Save E, Muller RU, Poucet B. Goal-Related Activity in Hippocampal Place Cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:472–482. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2864-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollup SA, Molden S, Donnett JG, Moser MB, Moser EI. Place fields of rat hippocampal pyramidal cells and spatial learning in the watermaze: Place fields in the watermaze. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1197–1208. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito R, Robbins TW, Pennartz CM, Everitt BJ. Functional Interaction between the Hippocampus and Nucleus Accumbens Shell Is Necessary for the Acquisition of Appetitive Spatial Context Conditioning. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6950–6959. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1615-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings JH, Ung RL, Resendez SL, Stamatakis AM, Taylor JG, Huang J, Veleta K, Kantak PA, Aita M, Shilling-Scrivo K, et al. Visualizing Hypothalamic Network Dynamics for Appetitive and Consummatory Behaviors. Cell. 2015;160:516–527. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackstedt LA, Kalivas PW. Glutamate and reinstatement. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaLumiere RT, Kalivas PW. Glutamate release in the nucleus accumbens core is necessary for heroin seeking. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3170–3177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5129-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazev AB, Herzog TA, Brandon TH. Classical conditioning of environmental cues to cigarette smoking. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:56–63. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Gu H, Loughead J, Ruparel K, Yang Y, Stein EA. Large-Scale Brain Network Coupling Predicts Acute Nicotine Abstinence Effects on Craving and Cognitive Function. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:523. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb S, Leutgeb JK, Barnes CA, Moser EI, McNaughton BL, Moser MB. Independent codes for spatial and episodic memory in hippocampal neuronal ensembles. Science. 2005;309:619–623. doi: 10.1126/science.1114037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AJ, Kramar E, Matheos DP, White AO, Kwapis J, Vogel-Ciernia A, Sakata K, Espinoza M, Wood MA. Promoter-Specific Effects of DREADD Modulation on Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity and Memory Formation. J Neurosci. 2016;36:3588–3599. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3682-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers RA, Zavala AR, Neisewander JL. Dorsal, but not ventral, hippocampal lesions disrupt cocaine place conditioning. Neuroreport. 2003;14:2127–2131. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200311140-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers RA, Zavala AR, Speer CM, Neisewander JL. Dorsal hippocampus inhibition disrupts acquisition and expression, but not consolidation, of cocaine conditioned place preference. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:401–412. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel EA, Nimmerjahn A, Schnitzer MJ. Automated analysis of cellular signals from large-scale calcium imaging data. Neuron. 2009;63:747–760. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napier TC, Herrold AA, de Wit H. Using conditioned place preference to identify relapse prevention medications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013a;37:2081–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napier TC, Herrold AA, de Wit H. Using conditioned place preference to identify relapse prevention medications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013b;37:2081–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygard SK, Hourguettes Nicholas J, Sobczak Gabe G, Carlezon WAJ, Bruchas MR. M.R. Stress-induced reinstatement of nicotine preference requires Dynorphin/Kappa Opioid activity in the Basolateral Amygdala. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0953-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penton RE, Quick MW, Lester RAJ. Short- and Long-Lasting Consequences of In Vivo Nicotine Treatment on Hippocampal Excitability. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2584–2594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4362-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR. Nicotine as a modulator of behavior: beyond the inverted U. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:493–499. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00230-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Kenny PJ. Molecular mechanisms underlying behaviors related to nicotine addiction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:a012112. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portugal GS, Al-Hasani R, Fakira AK, Gonzalez-Romero JL, Melyan Z, McCall JG, Bruchas MR, Moron JA. Hippocampal Long-Term Potentiation Is Disrupted during Expression and Extinction But Is Restored after Reinstatement of Morphine Place Preference. J Neurosci. 2014;34:527–538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2838-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resendez SL, Jennings JH, Ung RL, Namboodiri VMK, Zhou ZC, Otis JM, Nomura H, McHenry JA, Kosyk O, Stuber GD. Visualization of cortical, subcortical and deep brain neural circuit dynamics during naturalistic mammalian behavior with head-mounted microscopes and chronically implanted lenses. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:566–597. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL. DREADDs for Neuroscientists. Neuron. 2016;89:683–694. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin A, Geva N, Sheintuch L, Ziv Y. Hippocampal ensemble dynamics timestamp events in long-term memory. eLife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.12247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum G, Eichenbaum H. Information coding in the rodent prefrontal cortex. II Ensemble activity in orbitofrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:751–762. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.2.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjulson L, Peyrache A, Cumpelik A, Cassataro D, Buzsáki G. Cocaine place conditioning strengthens location-specific hippocampal inputs to the nucleus accumbens. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniyan M, Dani JA. Dopaminergic and cholinergic learning mechanisms in nicotine addiction: Learning mechanisms in nicotine addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1349:46–63. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theis L, Berens P, Froudarakis E, Reimer J, Román Rosón M, Baden T, Euler T, Tolias AS, Bethge M. Benchmarking Spike Rate Inference in Population Calcium Imaging. Neuron. 2016;90:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouche S, Perestenko PV, van de Ven GM, Bratley CT, McNamara CG, Campo-Urriza N, Black SL, Reijmers LG, Dupret D. Recoding a cocaine-place memory engram to a neutral engram in the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:564–567. doi: 10.1038/nn.4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien JZ, Huerta PT, Tonegawa S. The essential role of hippocampal CA1 NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in spatial memory. Cell. 1996;87:1327–1338. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: update of the last decade. Addict Biol. 2007;12:227–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Portugal GS, Fakira AK, Melyan Z, Neve R, Lee HT, Russo SJ, Liu J, Morón JA. Hippocampal GluA1-containing AMPA receptors mediate context-dependent sensitization to morphine. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2011;31:16279–16291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3835-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Allen WE, Thompson KR, Tian Q, Hsueh B, Ramakrishnan C, Wang AC, Jennings JH, Adhikari A, Halpern CH, et al. Wiring and Molecular Features of Prefrontal Ensembles Representing Distinct Experiences. Cell. 2016;165:1776–1788. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrindast MR, Lashgari R, Rezayof A, Motamedi F, Nazari-Serenjeh F. NMDA receptors of dorsal hippocampus are involved in the acquisition, but not in the expression of morphine-induced place preference. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;568:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Kalivas PW. N-acetylcysteine reduces extinction responding and induces enduring reductions in cue- and heroin-induced drug-seeking. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:338–340. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziv Y, Burns LD, Cocker ED, Hamel EO, Ghosh KK, Kitch LJ, El Gamal A, Schnitzer MJ. Long-term dynamics of CA1 hippocampal place codes. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:264–266. doi: 10.1038/nn.3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video S1. Ca2+ imaging and detection of transients during place preference behavior, Related to Figure 2,4,5.

Left panel: ∆F/F0 video recording during CPP test in freely moving mice. Six neurons have been randomly selected and outlined in different colors.

Right panel: Time traces of Ca2+ transients for each neuron outlined in the left panel are displayed in corresponding colors.

Video S2. Video S2. Tracking Ca2+ transient activity during conditioned place preference behavior, Related to Figure 2,4,5.

Top left panel: Video (40× normal speed) of a freely-moving mouse with implanted GRIN lens and mini-endoscope during a CPP test.

Bottom left panel: real time dorsal-CA1 Ca2+ transient recording during CPP test.

Top right panel: Heat map of Ca2+ transients derived from events detected in bottom left panel. Video is rebuilt using PCA/ICA and event detection analyses.

Bottom right panel: Cumulative map displaying cell registration during CPP test. Individual white ovals indicate individual cells detected from heat map analysis in top right panel.