Abstract

Actomyosin contractility originating from interactions between F-actin and myosin facilitates various structural reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. Cross-linked actomyosin networks show tendency to contract to single or multiple foci, which has been investigated extensively in numerous studies. Recently, it was suggested that suppression of F-actin buckling via an increase in bending rigidity significantly reduces network contraction. In this study, we demonstrate that networks may show the largest contraction at intermediate bending rigidity, not at the lowest rigidity, if filaments are severed by buckling arising from myosin activity as demonstrated in recent experiments; if filaments are very flexible, frequent severing events can severely deteriorate network connectivity, leading to formation of multiple small foci and low network contraction. By contrast, if filaments are too stiff, networks exhibit minimal contraction due to inhibition of filament buckling. This study reveals that buckling-induced filament severing can modulate contraction of active cytoskeletal networks, which has been neglected to date.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Living cells need to generate mechanical forces to perform their physiological functions.1 The ability of cells to generate forces originates mainly from a non-equilibrium biopolymer network called the actin cytoskeleton.2 Myosin motor proteins walk on actin filaments (F-actin) in the actin cytoskeleton by consuming chemical energy stored in ATP, which results in tensile forces.3 The actomyosin contractility facilitates structural reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton in cells.4 Numerous in vitro experiments have demonstrated that reconstituted actin gels consisting of F-actins, actin cross-linking proteins (ACPs), and myosin motors exhibit active contraction to single or multiple foci. For example, it was shown that contraction of the actin gels emerges above critical motor density with intermediate levels of ACP density5 and takes place via multi-stage aggregation6 by driving initially well-connected networks to a critical state.7 In addition, we and our colleagues recently showed that networks contract at a rate proportional to network size via in vitro and numerical/analytical models, which is reminiscent of telescopic contraction of sarcomeres in muscle cells.8 It was also found that buckling induced by compressive forces arising from myosin activity plays a crucial role for contraction of actin gels9, consistent with theoretical predictions.10,11 A recent computational study showed that suppression of F-actin buckling can significantly slow down contraction.12 In general, myosin activity can drive actomyosin networks to either of three different states: negligible contraction, contraction to a single focus, or contraction to multiple foci. Known key factors determining the final state of networks are i) network connectivity regulated by cross-linking level and F-actin length and ii) destabilization of ACPs caused by forces exerted from motors.7,12-14

We recently demonstrated that severing of F-actin facilitated by buckling arising from external shear strain can induce distinct stress relaxation in passive cross-linked actin networks.15 Interestingly, severing was also observed during the active contraction of actomyosin networks.9 However, the role of F-actin severing in the myosin-driven network contraction has not been investigated to date. In this study, using an agent-based computational model, we investigated how F-actin severing induced by buckling modulates contraction of cortex-like thin actomyosin networks. We found that the buckling-induced F-actin severing significantly modulates network contraction, which has not demonstrated before.

Method

Model overview

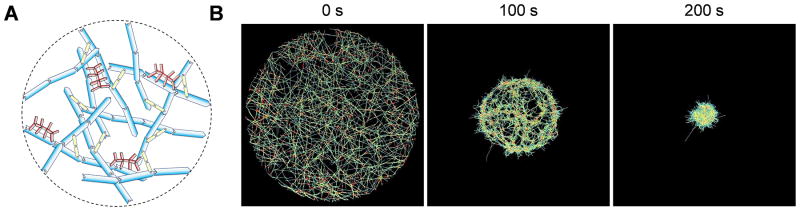

We employed our previous Brownian dynamics model for studying the contraction of actomyosin networks (Fig. 1).14,16 Detailed descriptions about the model and parameter values used in this study can be found in the Supplementary Information. In the model, F-actin, ACP, and motor are simplified by interconnected cylindrical segments. F-actin is comprised of serially connected cylindrical segments with polarity (barbed and pointed ends). ACPs consist of two cylindrical segments. Each motor has a backbone connected with 8 arms. A motor arm represents 8 myosin heads. Motions of the segments are governed by the Langevin equation with the Euler integration scheme. Deterministic forces include bending and extensional forces that maintain equilibrium angles and lengths formed by the segments, respectively, and repulsive forces that account for volume-exclusion effects between F-actins. Stochastic forces are applied to induce thermal fluctuation. ACPs bind to F-actin at a constant rate and also unbind from F-actin in a force-dependent manner. A motor arm binds to F-actin and walks toward the barbed end.

Fig. 1.

Contraction of actomyosin networks is investigated using an agent-based computational model. (A) Schematic diagram showing a circular network consisting of actin filaments (F-actin, cyan), actin crosslinking proteins (yellow), and motors (red). The three constituents are simplified via cylindrical segments. (B) Morphology of networks at t = 0, 100, and 200 s during contraction. Densities of motors and ACPs are 0.08 and 0.04, respectively.

Severing of F-actin

F-actins can be severed at a rate depending on bending angle as in our previous model.15 Severing of F-actin is simulated by breaking a chain between two adjacent points on the F-actin, which corresponds to disappearance of one actin segment. The sum of two adjacent bending angles on F-actin, θs,A, is calculated, and we assume that a severing rate, ks,A, exponentially increases as θs,A increases:

| (1) |

where is a zero-angle severing rate constant, and λs,A defines sensitivity to θs,A. This severing model was verified by comparing with in vitro experiments as described in the supplementary information.15

Network assembly

A very thin computational domain (20×20×0.1 μm) is employed without a periodic boundary condition. F-actin, ACP, and motor are self-assembled to a cross-linked actomyosin network within a circular space whose radius is 8 μm (Fig. 1B). During the network assembly, actin monomers are nucleated and polymerized into F-actin. ACPs bind to F-actin to form functional cross-links between pairs of F-actins. Motors are assembled into thick filaments, and motor arms bind to F-actin without walking motion. After the network assembly, motors start walking on F-actin, facilitating network contraction.

Quantification of network contraction

Network contraction is calculated using the x and y coordinates of endpoints of actin segments. Assuming that they are located on a single x-y plane, we create the spatial density map of the endpoints at the final time point of each simulation (Fig. S1A). By decreasing resolution of the map, a three-dimensional histogram is generated to automatically detect the number of foci (Fig. S1B). In the histogram, locations with actin density above a threshold value are considered to be potential centers of foci. If several potential centers are adjacent to each other in the histogram, they are considered to be a single focus. Once the number of foci is identified, we back-trace the endpoints of actin segments that belong to each focus up to the first time point in order to calculate contraction at each time point. For each focus, we first calculate its center by averaging the x and y positions of the actin endpoints. Then, distances between the center and endpoints that belong to the focus are averaged to calculate its mean radius, Ri(t). The extent of network contraction (ξ) is calculated as follows:

| (2) |

where N is the number of foci. Note that 0 corresponds to no contraction, whereas 1 means maximal contraction. An instantaneous contraction rate at each time point is determined by calculating the rate of a change in ξ over time . We define a steady state to be a time point when becomes less than ten percent of . The time required for reaching the steady state is termed τss, and the average contraction rate is calculated by dividing ξ at the steady state (ξss) by τss.

Results

Densities of motors and ACPs regulate contraction of actomyosin networks

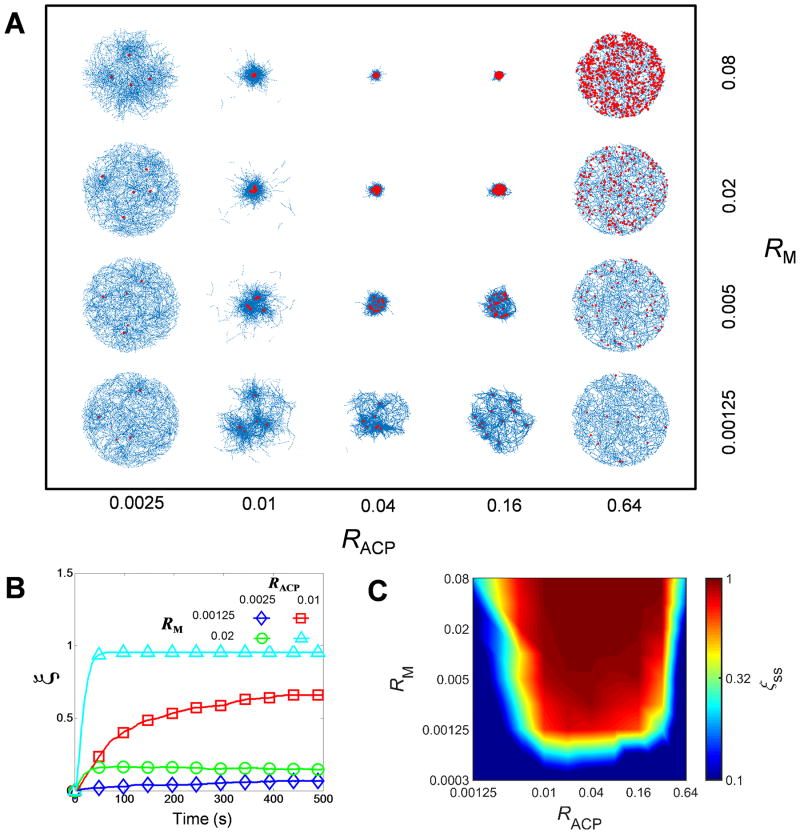

First, we evaluate the contraction of actomyosin networks at wide ranges of densities of motor (RM) and ACP (RACP) in the absence of F-actin severing. Note that RACP and RM are molar ratios defined with respect to actin concentration. In all cases, contraction initially rises at a different rate and eventually reaches a steady-state level (Fig. 2B). At the steady state, motors aggregate to single or multiple aggregates depending on conditions (Fig. 2A). Note that there is not a volume-exclusion effect between motors, so motors may overlap with each other in space, which can lead to very compact motor aggregates. Unlike motors, distribution of F-actins does not show noticeable discontinuity after contraction regardless of the number of motor aggregates. Large contraction greater than 50% occurs only above critical RM with intermediate values of RACP (Fig. 2C). A minimum amount of motors are required to obtain cooperativity between local motor activities, resulting in the critical .17 If there are an insufficient number of ACPs, connectivity between F-actins is too poor for motors to generate enough forces to contract networks. However, as RM is higher, the minimum amount of ACPs required for large contraction is smaller because motors can also behave as tentative cross-linkers. If average length of F-actins (<Lf>) is decreased from 2.53 μm to 1.74 μm, more ACPs are needed for large network contraction since a network with shorter F-actins has poorer connectivity compared to that with longer F-actins at the same cross-linking level (Fig. S2A). By contrast, if there are too many ACPs in a network, buckling of F-actins is suppressed either by a decrease in cross-linking distance or formation of F-actin bundles. Therefore, networks show smaller contraction above a certain level of because buckling is required for significant network contraction as predicted by theories (Fig. 2C).10,11 A 16-fold increase in bending stiffness of F-actin (κb,A) reduces because buckling can be suppressed more easily with stiffer F-actins even at larger cross-linking distance or with a less extent of F-actin bundling (Fig. S2B). A decrease in <Lf> also reduces since motors generate weaker forces in a network with poorer connectivity although cross-linking distance and F-actin bundling are similar (Fig. S2A). These results showing large contraction only at and are very similar to observations from in vitro experiments using an actin gel consisting of actin, skeletal muscle myosin II, and α-actinin.5 A computational study using a highly simplified model predicted that network contraction can be large at high RACP and intermediate RM if volume-exclusion effects are negligible.17 However, we did not observe the secondary regime for large contraction. This might be attributed to indirect consideration of volume-exclusion effects between motors and ACPs due to a limited number of binding sites on each actin segment (40). In addition, large contraction emerging at the intermediate range of RACP is also consistent with conclusion of a recent computational study that the degree of connectivity determines network contraction.12 In sum, we found that large network contraction requires a sufficient amount of motors, enough network connectivity, and F-actin buckling. For the following studies, we focused on the narrower range of RACP between 0.005 and 0.08 since we were interested only in a regime where significant network contraction appears without F-actin severing in Fig. 2C.

Fig. 2.

Network contraction is regulated by densities of motors (RM) and ACPs (RACP). Contraction was evaluated under various RM and RACP. (A) Network morphology with actins and motors represented by blue and red, respectively. Note that motors can aggregate very tightly due to the absence of a volume-exclusion effect between them. (B) Time evolution of the extent of contraction (ξ) for four different cases. (C) ξ measured at a steady state (ξss). A minimum amount of motors are necessary to obtain cooperativity between local myosin activities. If there are an insufficient number of ACPs, motors cannot generate forces due to very poor network connectivity. By contrast, if there are too many ACPs, buckling is suppressed, which leads to small contraction. Thus, large network contraction occurs above critical RM with intermediate RACP.

Buckling-induced severing may lead to the largest network contraction at intermediate κb,A

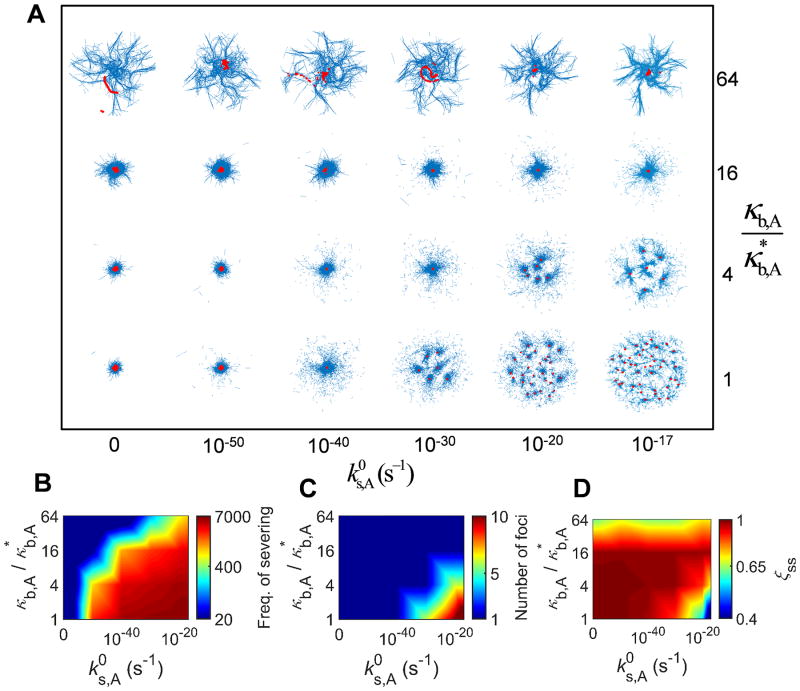

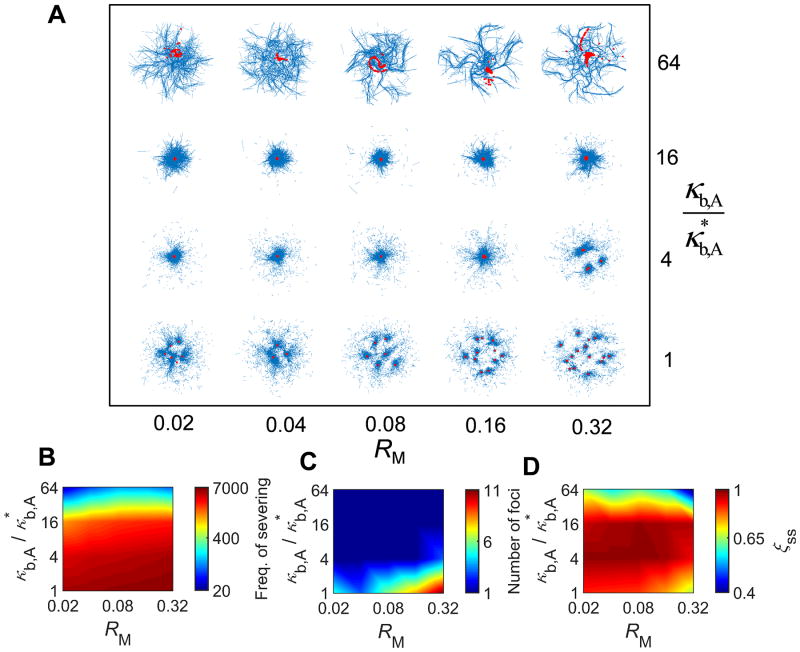

Recent in vitro experiments have demonstrated that F-actins can be severed spontaneously due to an increase in their bending angle caused by thermal fluctuation, and the probability of severing is significantly enhanced by binding of cofilin.18, 19 Since buckling also increases bending angle of F-actins, it can mediate severing of F-actins. We recently showed that external shear strain applied to passive cross-linked actin networks can facilitate severing by making a portion of F-actins buckled, and that the severing induces a very distinct stress relaxation in the passive networks.15 Considering that buckling also takes place during the active contraction driven by motors, F-actin severing induced by the buckling has potential to play an important role in the network contraction.9 By incorporating the severing model implemented in our previous study15, we evaluated effects of the severing on contractile behaviors. Specifically, we measured contraction at wide ranges of a zero-angle severing rate constant ( ) and κb,A (Fig. 3), with RM = 0.08 and RACP = 0.02 where very large contraction to a single focus occurs in the absence of severing. As expected, networks show smaller contraction with 64-fold higher κb,A since F-actin buckling is suppressed (Fig. 3D). However, motors form aggregation in various fashions, leaving aster-like F-actin structures (Fig. 3A), which is reminiscent of contraction of microtubule networks observed in several experiments.20, 21 This contraction is mediated by polarity sorting, meaning that barbed ends of F-actins are brought to the center of the aster-like structures by motors.12 With higher and lower κb,A, F-actins are severed more frequently during contraction (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, under the condition resulting in numerous severing events, a network is transformed to multiple foci with small contraction because F-actins are fragmented into short filaments during contraction, leading to severe deterioration of network connectivity (Figs. 3A, C). Thus, in the presence of F-actin severing, the network contraction can be maximal at intermediate levels of κb,A, not the smallest level. Time required for reaching a steady state (τss) is proportional to κb,A but is almost independent of (Fig. S3A), indicating that a network comprised of stiffer filaments resists myosin-driven contraction more. An average contraction rate shows dependence on and κb,A similar to dependence of the final contraction (ξss) on and κb,A although it shows stronger dependence on κb,A (Fig. S3B).

Fig. 3.

If filaments can be severed due to buckling, intermediate bending rigidity can lead to the largest network contraction. We evaluated network contraction with diverse bending stiffness of filaments (κb,A) and zero-angle severing rate constant ( ) at RM = 0.08 and RACP = 0.02. (A) Morphology of networks with actins and motors represented by blue and red, respectively. (B) Frequency of filament severing. (C) Number of foci measured at a steady state. (D) ξss evaluated at a steady state. If κb,A is very high, buckling is inhibited, leading to small contraction and formation of motor foci and aster-like actin structures. Higher and lower κb,A result in formation of multiple foci with small contraction because filament severing occurs very frequently under such conditions, severely deteriorating network connectivity. Thus, optimal intermediate κb,A exists at high .

It is not feasible to change bending rigidity of F-actins in experiments over the range tested in this study although it is known that the bending rigidity is slightly varied by binding of actin-associated proteins, such as phalloidin, calponin, and tropomyosin.22-24 However, cases with 64-fold higher κb,A (corresponding to the persistence length of 0.58 mm) may be compared with networks of microtubules whose persistence length is ∼ 5 mm.25 As mentioned earlier, in those cases, we observed formation of structures similar to microtubule networks contracted by motors. By contrast, it is viable to modulate the F-actin severing rate by including a different amount of cofilin.19 It will be interesting to test our predictions using reconstituted actomyosin networks with various concentrations of cofilin.

Networks containing more motors and fewer ACPs show optimal κb,A more apparently

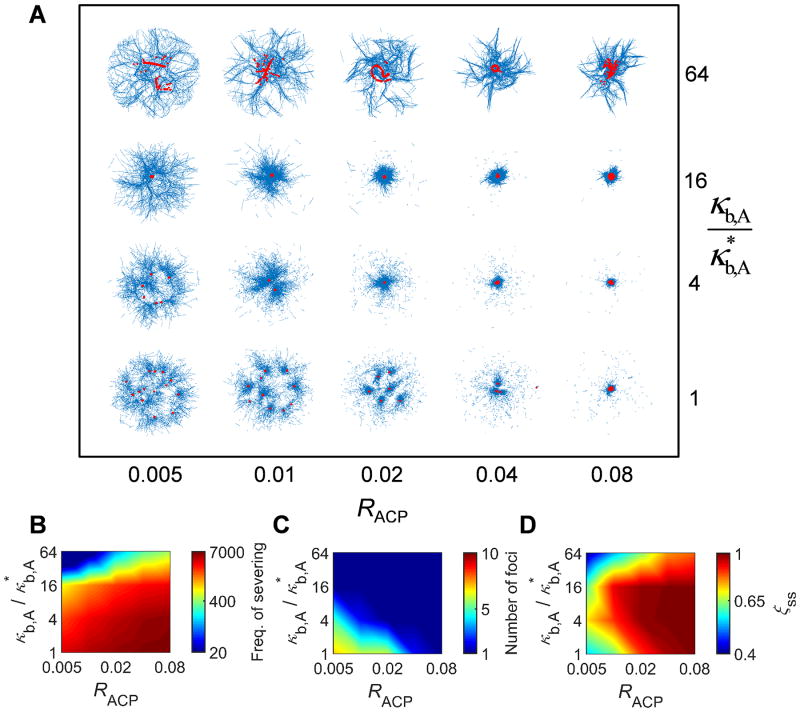

We further investigated conditions under which the optimal intermediate κb,A exists. is fixed at 10-30 s-1 while RACP is varied significantly from the reference value, 0.02, and κb,A is increased up to a 64-fold higher value as before (Fig. 4). F-actin buckling occurs more frequently at higher RACP (Fig. 4B), which is consistent with our previous study15. Buckling of F-actins highly confined by many cross-linking points results in sharp curvature (i.e. large local bending angle), facilitating numerous severing events. Note that the highest RACP tested here is 0.08 which is much lower than the critical RACP in Fig. 2C above which buckling is inhibited, ∼ 0.32. By contrast, if F-actins are loosely confined, buckling with mild curvature is not always followed by severing. It was observed the existence of the optimal intermediate κb,A is more conspicuous at lower RACP (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, at high RACP, the contraction is very large and leads to a single focus despite numerous severing events since enhancement of network connectivity via more ACPs is superior to deterioration of connectivity induced by F-actin severing during contraction (Figs. 4A, C). Since severing takes place in conjunction with an increase in effective actin concentration during contraction, ACPs can cross-link fragmented short F-actins. This is not identical to a situation where very short F-actins are cross-linked by numerous ACPs before contraction. If initial actin concentration is not very high, ACPs cannot cross-link very short F-actins into a percolated network regardless of their density. We also observe that τss is greater with higher RACP because networks become much stiffer and thus resist contraction to a much higher degree under such conditions. τss is still proportional to κb,A as seen in Fig. S3A. As a result, the average contraction rate is greater with higher RACP and lower κb,A (Fig. S4B).

Fig. 4.

The optimal intermediate bending rigidity is more apparent in loosely cross-linked networks. We probed network contraction over a wide range of RACP and κb,A with = 10-30 s-1 and RM = 0.08. Here, the range of RACP is narrowed to 0.005-0.08 to consider only a regime where significant network contraction appears without F-actin severing in Fig. 2C. (A) Network morphology showing actins (blue) and motors (red). (B) Frequency of filament severing. (C) Number of foci evaluated at a steady state. (D) ξss measured at a steady state. If RACP is smaller, the range of κb,A leading to large contraction becomes narrower. By contrast, if RACP is sufficiently high, networks contract to a single focus regardless of κb,A despite much more frequent severing events because enhancement of network connectivity resulting from more ACPs is superior to deterioration of connectivity induced by F-actin severing during contraction.

We also varied RM from a reference value, 0.08, with RACP fixed at 0.02 in order to probe the importance of the amount of motors for network contraction (Fig. 5). With higher RM, frequency of F-actin severing and the number of foci after full contraction tend to be greater because stronger forces exerted by more motors make more filaments buckled and thus severed (Figs. 5B, C). Since RACP is constant, this leads to significant reduction of network connectivity. As a result, networks show more apparent optimal intermediate κb,A with higher RM (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, this is opposite to the outcome obtained by an increase in RACP (Fig. 4D). Since larger forces can contract networks faster, τss is smaller with greater RM (Fig. S5A). As a result, the average contraction rate is greater with higher RM and lower κb,A (Fig. S5B).

Fig. 5.

With more motors, the optimal intermediate bending rigidity is more conspicuous. Network contraction was measured over a wide range of RM and κb,A with = 10-30 s-1 and RACP = 0.02. (A) Morphology of networks with actins (blue) and motors (red). (B) Frequency of filament severing. (C) Number of foci measured at a steady state. (D) ξss at a steady state. If there are a larger number of motors, more filaments are buckled and severed during contraction because larger compressive forces are exerted on filaments. Since RACP is constant in all cases, networks experiencing more severing events have poorer connectivity. Thus, an increase in RM leads to formation of multiple foci and small contraction at low κb,A and low contraction at high κb,A, making the optimal intermediate κb,A more apparent.

Conclusion

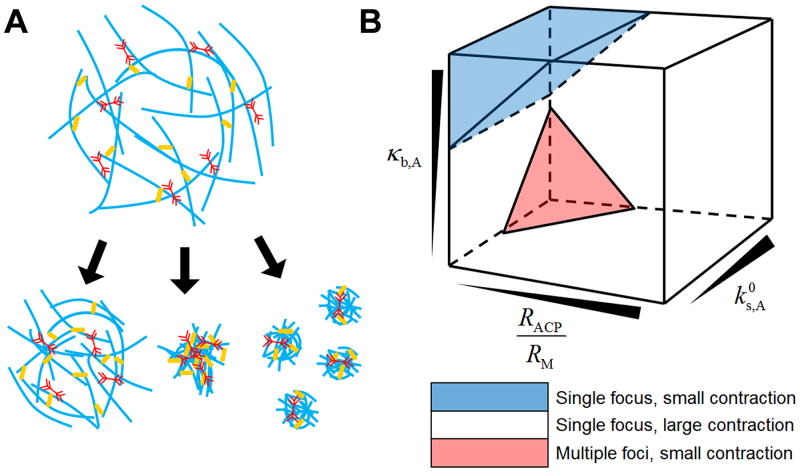

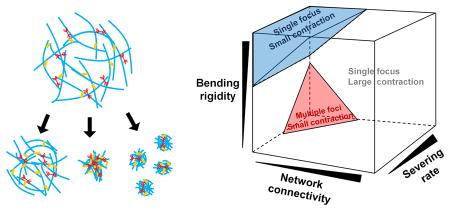

Based on results from this study, we conclude that actomyosin networks consisting of severable filaments can be in three different states after contraction: i) a single focus with large contraction, ii) a single focus with negligible contraction due to inhibition of F-actin buckling, iii) multiple foci with small contraction due to severe F-actin severing (Fig. 6A). Through further exploration of parametric spaces (Fig. S6), we created a three-dimensional phase diagram involved with four factors: motor density (RM), ACP density (RACP), zero-angle severing rate constant ( ), and bending stiffness of F-actin (κb,A) (Fig. 6B). Under most conditions, networks exhibit large contraction into a single focus. However, if the ratio of RACP to RM is low, two other regimes emerge. With sufficiently high κb,A, networks do not show large contraction because most of F-actins are not buckled. The critical κb,A above which contraction becomes substantially small is proportional to RACP/RM. Since F-actins are hardly buckled, the critical κb,A is not dependent on . By contrast, at small κb,A, F-actins are severed frequently if is high. These severing events can be critical for network contraction if RACP/RM is low since an insufficient number of ACPs cannot provide enough network connectivity to rescue a network from the deterioration of connectivity induced by severing. Thus, multiple foci appear as a result of contraction. Due to these two regimes with small contractions, an optimal level of κb,A leading to the largest contraction exists above a certain level of , which has not been identified in any previous study. Recent theoretical studies predicted that network contraction will always be suppressed with higher κb,A because they did not consider the possibility of F-actin severing induced by buckling. This novel finding provides a more comprehensive, realistic view about the contraction of actomyosin networks. We will extend our study by incorporating actin turnover dynamics, such as polymerization, depolymerization, and capping to capture and study network contraction under more physiologically relevant conditions.

Fig. 6.

Actomyosin networks contract to either of three possible states depending on bending stiffness of F-actin (κb,A), zero-angle severing rate constant ( ), ACP density (RACP), and motor density (RM). (A) The three possible states are i) small contraction with a single focus (left), ii) large contraction with a single focus (middle), and iii) small contraction with multiple foci (right). (B) Three-dimensional phase diagram showing regimes for the three states.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Science Foundation (1434013-CMMI) for TK and the support of the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (UL1TR001108) from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award for TK. This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1053575. The authors thank Michael P. Murrell for insightful discussions.

Notes and references

- 1.Lim CT, Zhou EH, Quek ST. Journal of biomechanics. 2006;39:195–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardel ML, Kasza KE, Brangwynne CP, Liu J, Weitz DA. Methods in cell biology. 2008;89:487–519. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)00619-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schliwa M, Woehlke G. Nature. 2003;422:759–765. doi: 10.1038/nature01601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murrell M, Oakes PW, Lenz M, Gardel ML. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2015;16:486–498. doi: 10.1038/nrm4012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendix PM, Koenderink GH, Cuvelier D, Dogic Z, Koeleman BN, Brieher WM, Field CM, Mahadevan L, Weitz DA. Biophysical journal. 2008;94:3126–3136. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soares e Silva M, Depken M, Stuhrmann B, Korsten M, MacKintosh FC, Koenderink GH. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:9408–9413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016616108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvarado J, Sheinman M, Sharma A, MacKintosh FC, Koenderink GH. Nat Phys. 2013;9:591–597. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linsmeier I, Banerjee S, Oakes PW, Jung W, Kim T, Murrell MP. Nature communications. 2016;7:12615. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murrell MP, Gardel ML. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:20820–20825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214753109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenz M. Physical Review X. 2014;4:041002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenz M, Thoresen T, Gardel ML, Dinner AR. Physical review letters. 2012;108:238107. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.238107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ennomani H, Letort G, Guerin C, Martiel JL, Cao W, Nedelec F, De La Cruz EM, Thery M, Blanchoin L. Current biology : CB. 2016;26:616–626. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Astrom JA, Kumar PBS, Karttunen M. Soft Matter. 2009;5:2869–2874. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung W, Murrell MP, Kim T. Computational Particle Mechanics. 2015;2:317–327. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jung W, Murrell MP, Kim T. ACS Macro Letters. 2016;5:641–645. doi: 10.1021/acsmacrolett.6b00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mak M, Zaman MH, Kamm RD, Kim T. Nature communications. 2016;7:10323. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, Wolynes PG. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:6446–6451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204205109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmoller KM, Niedermayer T, Zensen C, Wurm C, Bausch AR. Biophysical journal. 2011;101:803–808. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCullough BR, Grintsevich EE, Chen CK, Kang H, Hutchison AL, Henn A, Cao W, Suarez C, Martiel JL, Blanchoin L, Reisler E, De La Cruz EM. Biophysical journal. 2011;101:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster PJ, Furthauer S, Shelley MJ, Needleman DJ. eLife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.10837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belmonte JM, Nedelec F. eLife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.14076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isambert H, Venier P, Maggs AC, Fattoum A, Kassab R, Pantaloni D, Carlier MF. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270:11437–11444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen MH, Watt J, Hodgkinson JL, Gallant C, Appel S, El-Mezgueldi M, Angelini TE, Morgan KG, Lehman W, Moore JR. Cytoskeleton. 2012;69:49–58. doi: 10.1002/cm.20548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldmann WH. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2000;276:1225–1228. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gittes F, Mickey B, Nettleton J, Howard J. The Journal of cell biology. 1993;120:923–934. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.4.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Towns J, Cockerill T, Dahan M, Foster I, Gaither K, Grimshaw A, Hazlewood V, Lathrop S, Lifka D, Peterson GD, Roskies R, Scott JR, Wilkins-Diehr N. Computing in science & engineering. 2014;16:62–74. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.