Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by a non-cell autonomous motor neuron loss. While it is generally believed that the disease onset takes place inside motor neurons, different cell types mediating neuroinflammatory processes are considered deeply involved in the progression of the disease. On these grounds, many treatments have been tested on ALS animals with the aim of inhibiting or reducing the pro-inflammatory action of microglia and astrocytes and counteract the progression of the disease. Unfortunately, these anti-inflammatory therapies have been only modestly successful. The non-univocal role played by microglia during stress and injuries might explain this failure. Indeed, it is now well recognized that, during ALS, microglia displays different phenotypes, from surveillant in early stages, to activated states, M1 and M2, characterized by the expression of respectively harmful and protective genes in later phases of the disease. Consistently, the inhibition of microglial function seems to be a valid strategy only if the different stages of microglia polarization are taken into account, interfering with the reactivity of microglia specifically targeting only the harmful pathways and/or potentiating the trophic ones. In this review article, we will analyze the features and timing of microglia activation in the light of M1/M2 phenotypes in the main mice models of ALS. Moreover, we will also revise the results obtained by different anti-inflammatory therapies aimed to unbalance the M1/M2 ratio, shifting it towards a protective outcome.

Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, M1/M2 microglia, neuroinflammation, anti-inflammatory drugs, genetic modifiers, mutant SOD1 mice

ALS as a Composite Disease

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a multifactorial disease caused by genetic and non-inheritable components leading to motoneuron degeneration in the spinal cord, brain stem and primary motor cortex (Al-Chalabi and Hardiman, 2013). Most of ALS cases are sporadic (sALS), while 5%–20% report a familial history of the disease (fALS; Al-Chalabi et al., 2017). sALS and fALS share most neuropathological features and, from a clinical perspective, they appear very similar (Talbot, 2011). Pathological hallmarks characterizing degenerating motoneurons are cytoplasmic inclusions containing aggregated/ubiquitinated proteins as well as RNAs. Indeed, protein misfolding, with endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, impaired autophagy and damage to cytoskeleton are intracellular mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of the disease (Taylor et al., 2016). However, ALS appears as a composite syndrome where the aberrant cellular pathways may not derive solely from a conformational issue, but involve many aspects of cellular physiology: RNA processing and mitochondria homeostasis are compromised, oxidative stress is increased, excitotoxic pathways are enhanced, neurotrophic support is reduced, glial inflammatory response is oriented towards an harmful side (Rossi et al., 2016). Actually, more than 40 genes have been found mutated in ALS, affecting numerous cellular functions (Al-Chalabi et al., 2017), the most relevant of which are: a hexanucleotide repeat (GGGGCC) expansion in an intron of the C9orf72 gene (Dejesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Renton et al., 2011), supposed to generate toxic RNA species, loss of protein and/or harmful dipeptide-repeats formation (Haeusler et al., 2016); superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1; Rosen et al., 1993), forming toxic aggregates and interfering with mitochondrial functions and autophagy (Turner and Talbot, 2008). In this regard, transgenic SOD1 mice are so far the most widely used model to study ALS. Both active (SOD1G93A, SOD1G37R) and inactive (SOD1G85R) mutants show a phenotype characterized by a progressive paralysis and death (at 5, 7 and 8.5 months, respectively), caused by degeneration of motoneurons (limited to 40% in SOD1G85R mice), and exhibit gliosis within the spinal cord, brain stem and cortex (Philips and Rothstein, 2015), suggesting that neurodegeneration relies on a gain of toxic function of the protein. Other mutated proteins are fused in sarcoma (FUS; Kwiatkowski et al., 2009; Vance et al., 2009) and TAR-DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43; Neumann et al., 2006), involved in the maturation of mRNAs, found in cytoplasmic inclusions (Guerrero et al., 2016); proteins regulating cytoskeleton architecture, such as profiling-1 (Wu et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2016), and vesicle trafficking, as vesicle-associated membrane protein/synaptobrevin-associated membrane protein B (Nishimura et al., 2004; Tsuda et al., 2008); autophagy-linked proteins, among which sequestosome 1 (Teyssou et al., 2013), optineurin (Nakazawa et al., 2016) and TANK-binding protein kinase-1 (TBK-1; Cirulli et al., 2015; Freischmidt et al., 2015). Mutations in these genes also affect the function of cell types other than motoneurons. Indeed, ALS is non-cell autonomous, as astrocytes and microglia can participate to determine the disease phenotype by a local inflammatory response (neuroinflammation) and characterized by phenotypic transition, migration to the site of injury, proliferation and secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators (Philips and Rothstein, 2014). Glial activation leads to changes in the expression of a wide range of genes related to the production of soluble molecules, such as cytokines and chemokines, damage–associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), reactive nitrogen and oxygen species (ROS), giving rise to profound modifications in their interactions with neurons (Becher et al., 2017). Actually, a noticeable level of neuroinflammation has been detected in both sALS and fALS, as well as in transgenic models of the disease (Troost et al., 1989; Engelhardt and Appel, 1990; Schiffer et al., 1996; Hall et al., 1998; Henkel et al., 2004, 2006). Signs of microglia reactivity have been detected well before overt symptoms onset (Brites and Vaz, 2014; Tang and Le, 2016), concomitantly with loss of neuromuscular junctions (Gerber et al., 2012) and early motoneuron degeneration (Alexianu et al., 2001).

The role of microglia has been strengthened by recent studies opening new perspectives in the knowledge of the non-cell autonomous molecular pathways possibly contributing to ALS.

Lack of C9orf72 in a loss-of-function model of the disease produced no signs of motoneuron degeneration, but led to lysosomal accumulation and altered immune responses in macrophages and microglia (O’Rourke et al., 2016). Furthermore, the recently described ALS-susceptibility gene, TBK1, not only has a central function in autophagy processes, but is involved in innate immunity signaling pathways, regulating the production of interferon α (IFN α) and IFN β (Ahmad et al., 2016). A close relation between disruption of the autophagy machinery and microglial activation has been recently proposed (Plaza-Zabala et al., 2017): hence, an impaired autophagy linked to modifications in the response to pro-inflammatory stimuli and pathogen clearance by resident immune cells likely contributes to the etiopathology of the disease. Recent data show an earlier and more detrimental clinical course in SOD1G93A mice lacking telomerase (Linkus et al., 2016), evidencing therefore a possible aging effect on microglia priming in ALS. Indeed aged and mutant SOD1 (mSOD1)-expressing microglia display a common signature of gene expression, as well as specific patterns (Holtman et al., 2015).

In this review article, we therefore describe how the adaptive phenotypes of microglia participate to neurodegeneration in ALS, evidencing how the concept of a bipolar, protective vs. harmful, response of microglia has been rapidly changed in less than a decade. We also discuss how anti-inflammatory drugs have been used to polarize microglia towards a neuroprotective signature to control the extent of activation and if and how this has reached therapeutic benefits.

M1/M2 Phenotype in ALS

Overview

Microglia are largely considered as the brain’s resident immune cell, which has been classically described to exist in two states, resting and activated (Cherry et al., 2014). In the adult healthy brain, two-photon imaging showed that the so called “resting” microglia is, in actual facts, a highly dynamic population (Nimmerjahn et al., 2005), which actively screen their microenvironment with motile processes, exerting a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis (Luo and Chen, 2012). It is indicated as “surveillant” microglia and participates to many physiological functions, including synaptic pruning, adult neurogenesis and modulation of neuronal networks (Walton et al., 2006; Kettenmann et al., 2013).

This highly specific interaction with the extracellular environment is tightly regulated (Nimmerjahn et al., 2005; Parisi et al., 2016b), therefore these cells rapidly react to abnormalities, adopting a less ramified/amoeboid phenotype, corresponding to activated microglia (Luo and Chen, 2012; Cherry et al., 2014). Similarly to peripheral macrophages, the term activation has been associated at least with two distinct phenotypes, M1 (toxic) and M2 (protective), in response to different microenvironmental signals, in turn involved in the production of a variety of effector molecules (Du et al., 2016). Microglia recognize pathogens via pattern recognition receptors, which interact with classes of DAMPs derived from exogenous microorganisms or endogenous cell types involved in immunity processes, respectively. The interaction triggers a downstream gene induction program aimed at initiating cellular defense mechanisms, including the release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Colton, 2009; Kigerl et al., 2014).

In particular, in in vitro settings, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or IFN-γ stimulate “classically activated” M1 microglia, which release pro-inflammatory mediators. They include pro-inflammatory cytokines (interleukin [IL]-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α]), chemokines, prostaglandin E2, chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2, ROS and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; Bagasra et al., 1995; Du et al., 2016; Orihuela et al., 2016).

In contrast, “alternatively activated” M2 phenotype, which is induced by anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-10 or IL-13, suppresses inflammation, clears cellular debris through phagocytosis, promotes extracellular matrix reconstruction and supports neuron survival through the release of protective/trophic factors (Hu et al., 2015; Du et al., 2016; Tang and Le, 2016). “Acquired deactivation” represents another M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype and it is mainly induced by the uptake of apoptotic cells or exposure to anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (Tang and Le, 2016).

Microglia in ALS

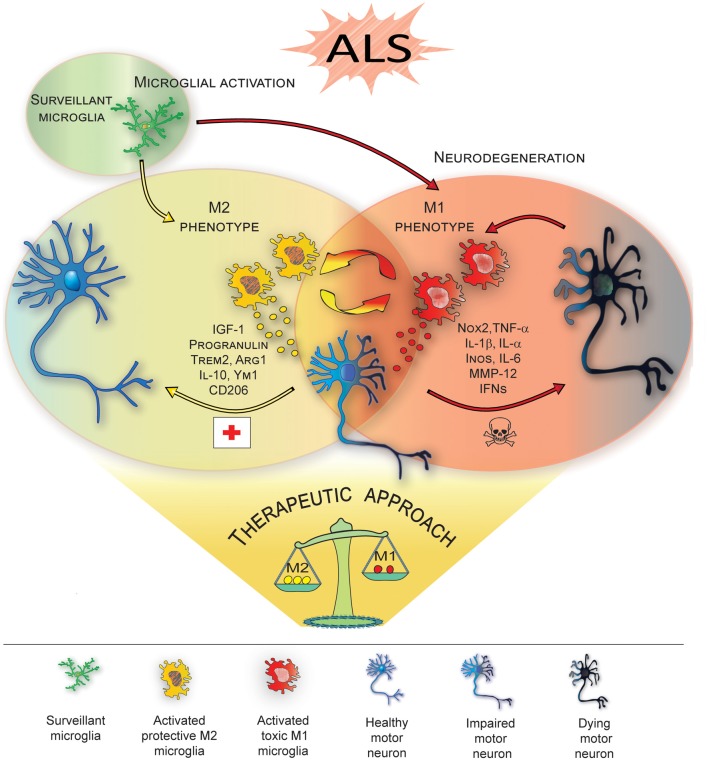

Studies investigating the progression of the disease in ALS mice indicate that, in vivo, resident microglia increase their number during disease progression, and their activation states represent a continuum between the two classical phenotypes, i.e., neuroprotective M2 vs. toxic M1 (Liao et al., 2012; Chiu et al., 2013; Figure 1). In line with this, the occurrence of two different phenotypes of microglial cells, on the basis of their morphology, has been recently described in SOD1G93A transgenic mice: type “R1”, showing short and poorly branched processes, which represents the vast majority of microglia in the early-stage of the disease and corresponding to early transformation of surveillant microglia, and type “R3” microglia, exhibiting large cell bodies with short and thick processes, which are typical of end-stage phases of the disease (Ohgomori et al., 2016). Consistently, microglia have been shown to exhibit, at the pre-onset phase of SOD1-mediated disease, an anti-inflammatory profile with attenuated TLR2 responses to controlled immune challenge, and a overexpression of anti-inflammatory IL-10 (Gravel et al., 2016). Subsequently, at disease onset and during the slowly progressing phase, the prevalent expression of specific M2 markers, (e.g., Ym1 and CD206), was detected in the lumbar spinal cords of ALS mice (Beers et al., 2011a). Eventually, in end-stage animals, a microglial phenotype expressing high levels of NOX2, the subunit of nicotinamide-adenine-dinucleotide-phosphate oxidase expressed by macrophages considered M1 prototypic marker, appears to be prevalent (Beers et al., 2011b).

Figure 1.

M1/M2 microglia polarization during amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-induced motor neuron degeneration. During ALS progression activated microglia represent a continuum between the neuroprotective M2 phenotype, which promotes tissue repair and supports neuron survival by releasing neuroprotective factors, vs. the toxic M1, which produces cytokines increasing inflammation and further supporting M1 polarization, thus contributing to neuronal death. Therapeutic approaches targeting microglia polarization and resulting in induction of the M2 phenotype are promising strategies to ameliorate local neurodegeneration and improve the clinical outcome of the disease (see Table 1 for details).

M1 ALS microglia appear hyper-reactive to inflammatory stimuli (D’Ambrosi et al., 2009) and the specific role of mutated proteins in driving this increased toxicity has been suggested by many studies (Beers et al., 2006; Xiao et al., 2007; Liao et al., 2012). Mutant forms of TDP-43 are able to activate microglia and upregulate the release of pro-inflammatory mediators, including NOX2, TNF-α and IL-1β (Zhao et al., 2015). Consistently, also the intracellular expression of high levels of TDP-43 underlies the occurrence of a more toxic microglial phenotype, when stimulated, in vitro, with LPS or ROS (Swarup et al., 2011).

Similarly, exogenous SOD1G93A or SOD1G85R induce, in vitro, morphological and functional activation of microglia, increasing their release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS (Zhao et al., 2010). In chimeric mice with both normal and mSOD1-expressing cells, non-neuronal cells that do not express mSOD1, including microglia, delay degeneration and significantly extend survival of mutant protein-expressing motoneurons (Clement et al., 2003). Interestingly, also mSOD1-expressing microglia underlie phenotypic transformation during the disease. More specifically, evidence has been provided that, when co-culturing different-aged mSOD1 microglia with WT motoneurons, mSOD1-expressing early-activated microglia exhibit neuroprotective features, enhancing neuronal survival, while end-stage derived mSOD1 microglia show toxic properties, increasing neuronal death rate (Liao et al., 2012). Additionally, mSOD1 microglia shows increased expression of molecular players of the ER stress pathway (Ito et al., 2009), which may be involved in their toxic phenotype.

At the molecular level, mutated proteins, including TDP-43 and FUS, induce the selective activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB), master regulator of inflammation (Frakes et al., 2014).

On this basis, the possibility to appropriately modulate microglial phenotypes, enhancing the anti-inflammatory properties and inhibiting or reducing M1 toxicity, could be a promising therapeutic strategy for ALS, therefore a comprehensive knowledge of both timing and molecular players of microglial activity is needed. However, emerging evidence suggests that the M1/M2 paradigm seems to be an oversimplification (Ransohoff, 2016) and substantial differences between microglia and peripheral macrophages, from which the terminology derives, should be carefully considered. As resident macrophages of the brain, microglia have an elaborate repertoire of brain specific functions, sustained by a peculiar gene expression profiling (Gautier et al., 2012). In vitro, phenotypic redirection is a feature of peripheral macrophages, while microglia exhibit a lower grade of plasticity (Parisi et al., 2016b). Coexistence of the two opposite phenotypes, more than transition from M2 to M1, during ALS progression has also been recently highlighted by several findings. For instance, beneficial components of inflammation, such as insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1), whose release is suppressed in a pro-inflammatory (M1) environment but encouraged in an M2 protective environment (Suh et al., 2013), is overexpressed by SOD1G93A microglia not only in pre-symptomatic stage, but also in end-stage (Chiu et al., 2008). Furthermore, a down-regulation of IL-6 over time, associated with an up-regulation of IL-1R antagonist, has been reported, suggesting the occurrence of an anti-inflammatory response (Chiu et al., 2008). Analysis of transcriptome changes of SOD1G93A microglia essentially confirmed these observations. They also evidenced that the activation of genes involved in anti-inflammatory pathways, including, Igf1, Progranulin and Trem2, coexists with the upregulation of genes related to potentially neurotoxic factors, among which Matrix metalloproteinase-12 and classical proinflammatory cytokines, (Chiu et al., 2013). Interestingly, critical differences in gene expression profiling among M1/M2 macrophages, LPS-activated microglia and SOD1G93A activated microglia emerge: while LPS-activated microglia show enriched in DNA replication-, cell cycle- and innate immune signaling-genes, SOD1G93A activated microglia are enriched in the transcripts of genes related to neurodegenerative diseases, e.g., AD, Huntington’s and Parkinson’s disease, suggesting a neurodegeneration-specific signature for ALS microglia. More interestingly, SOD1G93A-expressing microglia do not display a significant prevalence of M1 or M2 phenotypes at any time point during disease progression (Chiu et al., 2013). In line with this results, an increased expression of both iNOS (M1 marker) and arginase 1 (Arg1; M2 marker) has been shown to parallel the generalized increase of activated microglia in SOD1G93A mice (Lewis et al., 2014). Consistently, characteristics different from typical M1 or M2 phenotypes have been reported in end-stage SOD1G93A rats, which also show predominant microglial activation in most severely affected regions (lumbar spinal cord), as if several phenotypically different microglial subpopulations were present throughout differently affected regions of the CNS (Nikodemova et al., 2014).

Microglial Switch and Therapeutic Approaches in ALS Animal Models

Targeting the microglia has been the focus of neuroprotective strategies, based on pharmacological or genetic approaches, aimed at modulating microglia reactivity in the attempt to improve the clinical outcome in animal models of the disease (Table 1, Figure 1). In this regard, pioneer studies based on administration of minocycline, a tetracycline antibiotic that prevents microglial activation, showed that, when administered in both SOD1G93A and SOD1G37R mice before disease onset, it attenuates microglial activation and delays disease onset and mortality (Kriz et al., 2002; Van Den Bosch et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2002). On the other hand, when administered after the onset of the disease, it fails to improve clinical and/or pathological features, even increasing microgliosis (Keller et al., 2011). Interestingly, recent findings obtained in SOD1G37R mice have shown that minocycline specifically attenuates the M1 phenotype, without influencing the expression of M2 markers (Kobayashi et al., 2013; Table 1), thus highlighting the crucial role exerted by the modulation of M1/M2 balance in the therapeutic effectiveness.

Table 1.

Preclinical approaches affecting microglia M1/M2 phenotype in transgenic mutant superoxide dismutase1 (mSOD1) mice.

| Drug administered/Genes silenced | Action/Function | M1 modulation | M2 modulation | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMD3100 (Rabinovich-Nikitin et al., 2016) | CXCR4 antagonist | ↓TNF-α, IL-6 | Survival +10%, ↑onset, b.w., motor function | |

| BBG (Apolloni et al., 2014) | P2X7 antagonist | ↓NOX2, IL-1β; n.s.c. TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS | ↑BDNF, IL-10 | Survival n.s.c., ↑motor function |

| Bee venom (Yang et al., 2010) | anti-inflammation | TNF-α↓ | Survival +18%, ↑onset, motor function | |

| Celastrol (Kiaei et al., 2005b) | iNOS↓ | Survival +13%, ↑onset, b.w., motor function | ||

| Celecoxib/Rofecoxib + Creatine (Klivenyi et al., 2004) | COX-2 inhibitor | PGE2↓ | Survival +30%, ↑b.w., motor function | |

| Clemastine (Apolloni et al., 2016b) | Antihistamine | ↓CD68, gp91phox | ↑Arg1, BDNF | Survival n.c.s., ↑onset, |

| DL-NBP (Feng et al., 2012) | Neuroprotection | ↓TNF-α | Survival +42%, ↑b.w., motor function | |

| EGCG (Xu et al., 2006) | Neuroprotection | iNOS↓ | Survival +10%, onset +9%, | |

| hMSC (Zhou et al., 2013) | Stromal cells | ↓TNF-α, iNOS | Survival +10%, onset +6%, ↑motor function | |

| IL-1RA (Meissner et al., 2010) | IL-1R antagonist | Survival +4%, ↑motor function | ||

| Lenalidomide (Kiaei et al., 2006) | ↓ TNF-α | ↓TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β | ↑TGF-β1 | Survival +18%, ↑onset, b.w., motor function |

| *M-CSF (Gowing et al., 2009) | Cytokine | ↑TNF-α, IL-1β;↓IL-6, NOX2 | ↓IL-4; ↑TGF-β1 | Survival −3% |

| Minocycline (Kobayashi et al., 2013) | ↓glia activation | ↓TNF-α, IL-1β, INF-γ, CD86, CD68 | n.s.c. CD206, Arg1, IL-4, IL-10, Ym1 | Survival +54%, onset +15% |

| Nimesulide (Pompl et al., 2003) | COX-2 inhibitor | PGE2↓ | Survival n.d., ↑onset, motor function | |

| Pioglitazone (Kiaei et al., 2005a) | PPARγ agonist | ↓iNOS, COX2 | Survival +13%, ↑onset, b.w., motor function | |

| R723 (Tada et al., 2014) | JAK2 inhibitor | ↓CD11b, iNOS; n.s.c. TNF-α, IL6, IL-1β | n.s.c. Arg1, Ym1, IL-4 | n.s.c. |

| scAAV9-VEGF (Wang et al., 2016) | ↑ VEGF | ↓TNF-α, CD68 | ↑Arg1, Ym1 | Survival +10%, ↑b.w., motor function |

| Sulindac (Kiaei et al., 2005c) | COX inhibitor | COX2↓ | Survival +10%, ↑b.w., motor function | |

| Thalidomide (Kiaei et al., 2006) | ↓ TNF-α | ↓TNF-α; n.s.c. IL-1α, IL-1β | ↑TGF-β1 | Survival +12%, ↑onset, b.w., motor function |

| gp91phox− (Wu et al., 2006) | NOX2 inhibition | IL-1β n.s.c. | Survival +11% | |

| IL-1β−/− (Meissner et al., 2010) | IL-1β decrease | ↓IL-1β−/− | Survival +5% | |

| iNOS−/− (Martin et al., 2007) | iNOS inhibition | ↓iNOS | ↑Survival | |

| NOX2−/− (Marden et al., 2007) | NOX2 inhibition | ↓NOX2 | Survival +73%, ↑onset, b.w., motor function | |

| **TNF-α−/− (Gowing et al., 2006) | TNF-α decrease | ↓TNF-α | n.s.c. | |

| *xCT−/− (Mesci et al., 2015) | ↓ Glutamate release | Onset: ↑IL-1β, iNOS E.s.: ↓IL-1β, iNOS |

Onset: ↓Arg1, Ym1 L.s.:↑Arg1, Ym1 |

Survival n.s.c., onset −9%, ↑b.w. (at l.s.), motor function |

All trials were performed in SOD1G93A mice except the cases indicated with asterisks (* performed in SODG37R mice, ** performed both in SODG93A and SODG37R mice). The reported data refer to most effective results obtained in the cited article. Abbreviations: n.d., not described, n.s.c., non significant changes, ↑ increased, ↓ decreased; b.w., body weight, e.s., end stage, l.s., late symptomatic stage.

Hence, pharmacological modulation of molecular pathways related to microglial polarization has been explored. The hyperactivation of P2X7 receptors, strongly involved in neuroinflammatory response (Burnstock, 2008; Apolloni et al., 2009; Volonté et al., 2012; Sperlágh and Illes, 2014), has been described in microglia of both ALS patients and animal models (Yiangou et al., 2006; D’Ambrosi et al., 2009), where it is associated to the production of pro-inflammatory factors, including miR-125b (D’Ambrosi et al., 2009; Parisi et al., 2013, 2016a). Consistently, the administration of the P2X7 antagonist Brilliant Blue G (BBG), within a critical time frame, improves several features of the disease (Cervetto et al., 2013; Apolloni et al., 2014). BBG neuroprotection, obtained at late pre-onset administration, is supported by the upregulation of IL-10 and BDNF, associated to M2 phenotype, together with a reduction of NF-kB protein, NOX-2 and IL1β, markers of M1 polarization (Table 1). However, BBG administration at earlier phases fails to counteract disease progression. In this case, although it reduces M1 markers, it does not affect the expression of M2 mediators, whose neuroprotective properties seem to be essential to improve the clinical outcome (Apolloni et al., 2014).

Microglia-mediated neuroinflammation is also modulated by histamine (Ferreira et al., 2012; Volonté et al., 2015; Barata-Antunes et al., 2017). The antihistamine drug Clemastine, administered to SOD1G93A mice at the asymptomatic phase until the end-stage of disease, fails to improve clinical symptoms and lifespan, although it modulates the M1/M2 balance by reducing CD68, NOX2 and P2X7 expression and concomitantly up-regulating Arg1 (Apolloni et al., 2016b; Table 1). Conversely, when administered at the asymptomatic phase to the onset, it delays the disease onset and improves the motor functions and survival rate (Apolloni et al., 2016a). Clemastine also activates autophagy in SOD1G93A primary microglia, thus suggesting that targeting autophagy in microglia could be a promising therapeutic strategy (Apolloni et al., 2016a).

Alternative therapeutic strategies to shift the balance towards the M2 phenotype involve the use of trophic factors. Several findings showed that the delivery of viral vectors encoding growth factors, such as IGF-1, glial-derived neurotrophic factor, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) extends lifespan and slows the progression of the disease in ALS animal models (Acsadi et al., 2002; Kaspar et al., 2003; Azzouz et al., 2004; Dodge et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2016). Interestingly, the intrathecal injection of self-complementary adeno-associated-virus (scAAV)9-VEGF at disease onset decreases TNF-α, IL-1β and CD68 levels and increases those of Arg-1 and Ym-1 (Table 1), showing that the modulation of M1/M2 balance could support the protective effects correlated to VEGF administration (Wang et al., 2016).

Further, the deletion of the cystine/glutamate-antiporter xCT/Slc7a11 (xCT), a critical glial transporter system involved in the excessive glutamate release from M1 microglia, has provided additional finding on this matter. Indeed, xCT deletion at the early-stages of the disease, in fact, increases the expression of M1 marker IL1β and concurrently reduces M2 marker Ym1/Chil3, thus resulting in earlier disease onset. Conversely, lack of xCT, at the end-stage, increases Ym1/Chil3 and Arg1 expression, which possibly sustains the delay of disease progression (Mesci et al., 2015; Table 1).

These data underline that the modulation of microglia-specific pathways may ameliorate local neurodegeneration. However, growing evidence suggests that a successful therapeutic strategy for ALS could be obtained only interfering with different pathways in different cell types. In light of this, it was recently demonstrated that microglial NF-κB suppression combined with mSOD1 reduction in astrocytes and motoneurons results not only in attenuated neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, but also increases mice mean survival (Frakes et al., 2017), demonstrating that the redirection of microglia polarization may still be an effective strategy to counteract ALS when associated with the interception of other pathogenic mechanisms.

Author Contributions

MCG and ND wrote respectively section 2 and 1 and conceived, designed and revised the manuscript; VC wrote section 3; EM prepared the artwork; AS created the table; FM revised the work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nando and Elsa Peretti Foundation (Fabrizio Michetti—Contract number NaEPF 2016-033) and Università Cattolica del Sacri Cuore (linea D.3.2 2015 to FM) for financial support.

References

- Acsadi G., Anguelov R. A., Yang H., Toth G., Thomas R., Jani A., et al. (2002). Increased survival and function of SOD1 mice after glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor gene therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 13, 1047–1059. 10.1089/104303402753812458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad L., Zhang S.-Y., Casanova J.-L., Sancho-Shimizu V. (2016). Human TBK1: a gatekeeper of neuroinflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 22, 511–527. 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Chalabi A., Hardiman O. (2013). The epidemiology of ALS: a conspiracy of genes, environment and time. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9, 617–628. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Chalabi A., Van Den Berg L. H., Veldink J. (2017). Gene discovery in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: implications for clinical management. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 13, 96–104. 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexianu M. E., Kozovska M., Appel S. H. (2001). Immune reactivity in a mouse model of familial ALS correlates with disease progression. Neurology 57, 1282–1289. 10.1212/wnl.57.7.1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apolloni S., Amadio S., Parisi C., Matteucci A., Potenza R. L., Armida M., et al. (2014). Spinal cord pathology is ameliorated by P2X7 antagonism in a SOD1-mutant mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Dis. Model. Mech. 7, 1101–1109. 10.1242/dmm.017038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apolloni S., Fabbrizio P., Amadio S., Volonté C. (2016a). Actions of the antihistaminergic clemastine on presymptomatic SOD1–G93A mice ameliorate ALS disease progression. J. Neuroinflammation 13:191. 10.1186/s12974-016-0658-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apolloni S., Fabbrizio P., Parisi C., Amadio S., Volonte C. (2016b). Clemastine confers neuroprotection and induces an anti-inflammatory phenotype in SOD1G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol. Neurobiol. 53, 518–531. 10.1007/s12035-014-9019-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apolloni S., Montilli C., Finocchi P., Amadio S. (2009). Membrane compartments and purinergic signalling: P2X receptors in neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory events. FEBS J. 276, 354–364. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06796.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzouz M., Ralph G. S., Storkebaum E., Walmsley L. E., Mitrophanous K. A., Kingsman S. M., et al. (2004). VEGF delivery with retrogradely transported lentivector prolongs survival in a mouse ALS model. Nature 429, 413–417. 10.1038/nature02544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagasra O., Michaels F. H., Zheng Y. M., Bobroski L. E., Spitsin S. V., Fu Z. F., et al. (1995). Activation of the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase in the brains of patients with multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 92, 12041–12045. 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barata-Antunes S., Cristóvão A. C., Pires J., Rocha S. M., Bernardino L. (2017). Dual role of histamine on microglia-induced neurodegeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1863, 764–769. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher B., Spath S., Goverman J. (2017). Cytokine networks in neuroinflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 49–59. 10.1038/nri.2016.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers D. R., Henkel J. S., Xiao Q., Zhao W., Wang J., Yen A. A., et al. (2006). Wild-type microglia extend survival in PU.1 knockout mice with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 103, 16021–16026. 10.1073/pnas.0607423103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers D. R., Henkel J. S., Zhao W., Wang J., Huang A., Wen S., et al. (2011a). Endogenous regulatory T lymphocytes ameliorate amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice and correlate with disease progression in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 134, 1293–1314. 10.1093/brain/awr074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers D. R., Zhao W., Liao B., Kano O., Wang J., Huang A., et al. (2011b). Neuroinflammation modulates distinct regional and temporal clinical responses in ALS mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 25, 1025–1035. 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brites D., Vaz A. R. (2014). Microglia centered pathogenesis in ALS: insights in cell interconnectivity. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:117. 10.3389/fncel.2014.00117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. (2008). Purinergic signalling and disorders of the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 575–590. 10.1038/nrd2605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervetto C., Frattaroli D., Maura G., Marcoli M. (2013). Motor neuron dysfunction in a mouse model of ALS: gender-dependent effect of P2X7 antagonism. Toxicology 311, 69–77. 10.1016/j.tox.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry J. D., Olschowka J. A., O’Banion M. K. (2014). Neuroinflammation and M2 microglia: the good, the bad, and the inflamed. J. Neuroinflammation 11:98. 10.1186/1742-2094-11-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu I. M., Chen A., Zheng Y., Kosaras B., Tsiftsoglou S. A., Vartanian T. K., et al. (2008). T lymphocytes potentiate endogenous neuroprotective inflammation in a mouse model of ALS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 105, 17913–17918. 10.1073/pnas.0804610105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu I. M., Morimoto E. T., Goodarzi H., Liao J. T., O’Keeffe S., Phatnani H. P., et al. (2013). A neurodegeneration-specific gene-expression signature of acutely isolated microglia from an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model. Cell Rep. 4, 385–401. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli E. T., Lasseigne B. N., Petrovski S., Sapp P. C., Dion P. A., Leblond C. S., et al. (2015). Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identifies risk genes and pathways. Science 347, 1436–1441. 10.1126/science.aaa3650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement A. M., Nguyen M. D., Roberts E. A., Garcia M. L., Boillée S., Rule M., et al. (2003). Wild-type nonneuronal cells extend survival of SOD1 mutant motor neurons in ALS mice. Science 302, 113–117. 10.1126/science.1086071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton C. A. (2009). Heterogeneity of microglial activation in the innate immune response in the brain. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 4, 399–418. 10.1007/s11481-009-9164-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosi N., Finocchi P., Apolloni S., Cozzolino M., Ferri A., Padovano V., et al. (2009). The proinflammatory action of microglial P2 receptors is enhanced in SOD1 models for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Immunol. 183, 4648–4656. 10.4049/jimmunol.0901212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejesus-Hernandez M., Mackenzie I. R., Boeve B. F., Boxer A. L., Baker M., Rutherford N. J., et al. (2011). Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 72, 245–256. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge J. C., Treleaven C. M., Fidler J. A., Hester M., Haidet A., Handy C., et al. (2010). AAV4-mediated expression of IGF-1 and VEGF within cellular components of the ventricular system improves survival outcome in familial ALS mice. Mol. Ther. 18, 2075–2084. 10.1038/mt.2010.206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L., Zhang Y., Chen Y., Zhu J., Yang Y., Zhang H.-L. (2016). Role of microglia in neurological disorders and their potentials as a therapeutic target. Mol. Neurobiol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/s12035-016-0245-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt J. I., Appel S. H. (1990). IgG reactivity in the spinal cord and motor cortex in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 47, 1210–1216. 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530110068019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Peng Y., Liu M., Cui L. (2012). DL-3-n-butylphthalide extends survival by attenuating glial activation in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropharmacology 62, 1004–1010. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira R., Santos T., Gonçalves J., Baltazar G., Ferreira L., Agasse F., et al. (2012). Histamine modulates microglia function. J. Neuroinflammation 9:90. 10.1186/1742-2094-9-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frakes A. E., Braun L., Ferraiuolo L., Guttridge D. C., Kaspar B. K. (2017). Additive amelioration of ALS by co-targeting independent pathogenic mechanisms. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 4, 76–86. 10.1002/acn3.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frakes A. E., Ferraiuolo L., Haidet-Phillips A. M., Schmelzer L., Braun L., Miranda C. J., et al. (2014). Microglia induce motor neuron death via the classical NF-κB pathway in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuron 81, 1009–1023. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freischmidt A., Wieland T., Richter B., Ruf W., Schaeffer V., Muller K., et al. (2015). Haploinsufficiency of TBK1 causes familial ALS and fronto-temporal dementia. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 631–636. 10.1038/nn.4000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier E. L., Shay T., Miller J., Greter M., Jakubzick C., Ivanov S., et al. (2012). Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 13, 1118–1128. 10.1038/ni.2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber Y. N., Sabourin J. C., Rabano M., Vivanco M., Perrin F. E. (2012). Early functional deficit and microglial disturbances in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One 7:e36000. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowing G., Dequen F., Soucy G., Julien J. P. (2006). Absence of tumor necrosis factor-α does not affect motor neuron disease caused by superoxide dismutase 1 mutations. J. Neurosci. 26, 11397–11402. 10.1523/jneurosci.0602-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowing G., Lalancette-Hébert M., Audet J. N., Dequen F., Julien J. P. (2009). Macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) exacerbates ALS disease in a mouse model through altered responses of microglia expressing mutant superoxide dismutase. Exp. Neurol. 220, 267–275. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravel M., Béland L. C., Soucy G., Abdelhamid E., Rahimian R., Gravel C., et al. (2016). IL-10 controls early microglial phenotypes and disease onset in ALS caused by misfolded superoxide dismutase 1. J. Neurosci. 36, 1031–1048. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0854-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero E. N., Wang H., Mitra J., Hegde P. M., Stowell S. E., Liachko N. F., et al. (2016). TDP-43/FUS in motor neuron disease: complexity and challenges. Prog. Neurobiol. 145–146, 78–97. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeusler A. R., Donnelly C. J., Rothstein J. D. (2016). The expanding biology of the C9orf72 nucleotide repeat expansion in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 383–395. 10.1038/nrn.2016.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall E. D., Oostveen J. A., Gurney M. E. (1998). Relationship of microglial and astrocytic activation to disease onset and progression in a transgenic model of familial ALS. Glia 23, 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel J. S., Beers D. R., Siklos L., Appel S. H. (2006). The chemokine MCP-1 and the dendritic and myeloid cells it attracts are increased in the mSOD1 mouse model of ALS. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 31, 427–437. 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel J. S., Engelhardt J. I., Siklós L., Simpson E. P., Kim S. H., Pan T., et al. (2004). Presence of dendritic cells, MCP-1, and activated microglia/macrophages in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord tissue. Ann. Neurol. 55, 221–235. 10.1002/ana.10805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtman I. R., Raj D. D., Miller J. A., Schaafsma W., Yin Z., Brouwer N., et al. (2015). Induction of a common microglia gene expression signature by aging and neurodegenerative conditions: a co-expression meta-analysis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 3:31. 10.1186/s40478-015-0203-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Leak R. K., Shi Y., Suenaga J., Gao Y., Zheng P., et al. (2015). Microglial and macrophage polarization-new prospects for brain repair. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 11, 56–64. 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y., Yamada M., Tanaka H., Aida K., Tsuruma K., Shimazawa M., et al. (2009). Involvement of CHOP, an ER-stress apoptotic mediator, in both human sporadic ALS and ALS model mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 36, 470–476. 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar B. K., Lladó J., Sherkat N., Rothstein J. D., Gage F. H. (2003). Retrograde viral delivery of IGF-1 prolongs survival in a mouse ALS model. Science 301, 839–842. 10.1126/science.1086137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A. F., Gravel M., Kriz J. (2011). Treatment with minocycline after disease onset alters astrocyte reactivity and increases microgliosis in SOD1 mutant mice. Exp. Neurol. 228, 69–79. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettenmann H., Kirchhoff F., Verkhratsky A. (2013). Microglia: new roles for the synaptic stripper. Neuron 77, 10–18. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiaei M., Kipiani K., Chen J., Calingasan N. Y., Beal M. F. (2005a). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonist extends survival in transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 191, 331–336. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiaei M., Kipiani K., Petri S., Chen J., Calingasan N. Y., Beal M. F. (2005b). Celastrol blocks neuronal cell death and extends life in transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurodegener. Dis. 2, 246–254. 10.1159/000090364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiaei M., Kipiani K., Petri S., Choi D. K., Chen J., Calingasan N. Y., et al. (2005c). Integrative role of cPLA with COX-2 and the effect of non-steriodal anti-inflammatory drugs in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurochem. 93, 403–411. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03024.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiaei M., Petri S., Kipiani K., Gardian G., Choi D. K., Chen J., et al. (2006). Thalidomide and lenalidomide extend survival in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 26, 2467–2473. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5253-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kigerl K. A., de Rivero Vaccari J. P., Dietrich W. D., Popovich P. G., Keane R. W. (2014). Pattern recognition receptors and central nervous system repair. Exp. Neurol. 258, 5–16. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klivenyi P., Kiaei M., Gardian G., Calingasan N. Y., Beal M. F. (2004). Additive neuroprotective effects of creatine and cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurochem. 88, 576–582. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Imagama S., Ohgomori T., Hirano K., Uchimura K., Sakamoto K., et al. (2013). Minocycline selectively inhibits M1 polarization of microglia. Cell Death Dis. 4:e525. 10.1038/cddis.2013.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriz J., Nguyen M. D., Julien J. P. (2002). Minocycline slows disease progression in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 10, 268–278. 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski T. J., Jr., Bosco D. A., Leclerc A. L., Tamrazian E., Vanderburg C. R., Russ C., et al. (2009). Mutations in the FUS/TLS gene on chromosome 16 cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 323, 1205–1208. 10.1126/science.1166066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K. E., Rasmussen A. L., Bennett W., King A., West A. K., Chung R. S., et al. (2014). Microglia and motor neurons during disease progression in the SOD1G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: changes in arginase1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase. J. Neuroinflammation 11:55. 10.1186/1742-2094-11-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao B., Zhao W., Beers D. R., Henkel J. S., Appel S. H. (2012). Transformation from a neuroprotective to a neurotoxic microglial phenotype in a mouse model of ALS. Exp. Neurol. 237, 147–152. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkus B., Wiesner D., Meßner M., Karabatsiakis A., Scheffold A., Rudolph K. L., et al. (2016). Telomere shortening leads to earlier age of onset in ALS mice. Aging (Albany NY) 8, 382–393. 10.18632/aging.100904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X. G., Chen S. D. (2012). The changing phenotype of microglia from homeostasis to disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 1:9. 10.1186/2047-9158-1-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marden J. J., Harraz M. M., Williams A. J., Nelson K., Luo M., Paulson H., et al. (2007). Redox modifier genes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2913–2919. 10.1172/jci31265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L. J., Liu Z., Chen K., Price A. C., Pan Y., Swaby J. A., et al. (2007). Motor neuron degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mutant superoxide dismutase-1 transgenic mice: mechanisms of mitochondriopathy and cell death. J. Comp. Neurol. 500, 20–46. 10.1002/cne.21160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner F., Molawi K., Zychlinsky A. (2010). Mutant superoxide dismutase 1-induced IL-1β accelerates ALS pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 107, 13046–13050. 10.1073/pnas.1002396107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesci P., Zaïdi S., Lobsiger C. S., Millecamps S., Escartin C., Seilhean D., et al. (2015). System xC- is a mediator of microglial function and its deletion slows symptoms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice. Brain 138, 53–68. 10.1093/brain/awu312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa S., Oikawa D., Ishii R., Ayaki T., Takahashi H., Takeda H., et al. (2016). Linear ubiquitination is involved in the pathogenesis of optineurin-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Commun. 7:12547. 10.1038/ncomms12547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M., Sampathu D. M., Kwong L. K., Truax A. C., Micsenyi M. C., Chou T. T., et al. (2006). Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314, 130–133. 10.1126/science.1134108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikodemova M., Small A. L., Smith S. M., Mitchell G. S., Watters J. J. (2014). Spinal but not cortical microglia acquire an atypical phenotype with high VEGF, galectin-3 and osteopontin and blunted inflammatory responses in ALS rats. Neurobiol. Dis. 69, 43–53. 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn A., Kirchhoff F., Helmchen F. (2005). Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science 308, 1314–1318. 10.1126/science.1110647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura A. L., Mitne-Neto M., Silva H. C., Richieri-Costa A., Middleton S., Cascio D., et al. (2004). A mutation in the vesicle-trafficking protein VAPB causes late-onset spinal muscular atrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75, 822–831. 10.1086/425287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgomori T., Yamada J., Takeuchi H., Kadomatsu K., Jinno S. (2016). Comparative morphometric analysis of microglia in the spinal cord of SOD1 G93A transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 43, 1340–1351. 10.1111/ejn.13227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela R., McPherson C. A., Harry G. J. (2016). Microglial M1/M2 polarization and metabolic states. Br. J. Pharmacol. 173, 649–665. 10.1111/bph.13139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke J. G., Bogdanik L., Yáñez A., Lall D., Wolf A. J., Muhammad A. K., et al. (2016). C9orf72 is required for proper macrophage and microglial function in mice. Science 351, 1324–1329. 10.1126/science.aaf1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi C., Arisi I., D’Ambrosi N., Storti A. E., Brandi R., D’Onofrio M., et al. (2013). Dysregulated microRNAs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis microglia modulate genes linked to neuroinflammation. Cell Death Dis. 4:e959. 10.1038/cddis.2013.491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi C., Napoli G., Amadio S., Spalloni A., Apolloni S., Longone P., et al. (2016a). MicroRNA-125b regulates microglia activation and motor neuron death in ALS. Cell Death Differ. 23, 531–541. 10.1038/cdd.2015.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi C., Napoli G., Pelegrin P., Volonté C. (2016b). M1 and M2 functional imprinting of primary microglia: role of P2X7 activation and miR-125b. Mediators Inflamm. 2016:2989548. 10.1155/2016/2989548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips T., Rothstein J. D. (2014). Glial cells in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp. Neurol. 262, 111–120. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips T., Rothstein J. D. (2015). Rodent models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 69, 5.67.1–5.67.21. 10.1002/0471141755.ph0567s69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaza-Zabala A., Sierra-Torre V., Sierra A. (2017). Autophagy and microglia: novel partners in neurodegeneration and aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:e598. 10.3390/ijms18030598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompl P. N., Ho L., Bianchi M., McManus T., Qin W., Pasinetti G. M. (2003). A therapeutic role for cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. FASEB J. 17, 725–727. 10.1096/fj.02-0876fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich-Nikitin I., Ezra A., Barbiro B., Rabinovich-Toidman P., Solomon B. (2016). Chronic administration of AMD3100 increases survival and alleviates pathology in SOD1G93A mice model of ALS. J. Neuroinflammation 13:123. 10.1186/s12974-016-0587-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff R. M. (2016). A polarizing question: do M1 and M2 microglia exist? Nat. Neurosci. 19, 987–991. 10.1038/nn.4338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renton A. E., Majounie E., Waite A., Simón-Sánchez J., Rollinson S., Gibbs J. R., et al. (2011). A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72, 257–268. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen D. R., Siddique T., Patterson D., Figlewicz D. A., Sapp P., Hentati A., et al. (1993). Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 362, 59–62. 10.1038/362059a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S., Cozzolino M., Carrì M. T. (2016). Old versus new mechanisms in the pathogenesis of ALS. Brain Pathol. 26, 276–286. 10.1111/bpa.12355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer D., Cordera S., Cavalla P., Migheli A. (1996). Reactive astrogliosis of the spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 139, 27–33. 10.1016/0022-510x(96)00073-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperlágh B., Illes P. (2014). P2X7 receptor: an emerging target in central nervous system diseases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 35, 537–547. 10.1016/j.tips.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh H. S., Zhao M. L., Derico L., Choi N., Lee S. C. (2013). Insulin-like growth factor 1 and 2 (IGF1, IGF2) expression in human microglia: differential regulation by inflammatory mediators. J. Neuroinflammation 10:37. 10.1186/1742-2094-10-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup V., Phaneuf D., Dupre N., Petri S., Strong M., Kriz J., et al. (2011). Deregulation of TDP-43 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis triggers nuclear factor κB-mediated pathogenic pathways. J. Exp. Med. 208, 2429–2447. 10.1084/jem.20111313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada S., Okuno T., Hitoshi Y., Yasui T., Honorat J. A., Takata K., et al. (2014). Partial suppression of M1 microglia by Janus kinase 2 inhibitor does not protect against neurodegeneration in animal models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neuroinflammation 11:179. 10.1186/s12974-014-0179-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot K. (2011). Familial versus sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—a false dichotomy? Brain 134, 3429–3431. 10.1093/brain/awr296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Le W. (2016). Differential roles of M1 and M2 microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 53, 1181–1194. 10.1007/s12035-014-9070-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. A., Fournier C., Polak M., Wang L., Zach N., Keymer M., et al. (2016). Predicting disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 3, 866–875. 10.1002/acn3.348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teyssou E., Takeda T., Lebon V., Boillée S., Doukouré B., Bataillon G., et al. (2013). Mutations in SQSTM1 encoding p62 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: genetics and neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol. 125, 511–522. 10.1007/s00401-013-1090-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troost D., van den Oord J. J., de Jong J. M., Swaab D. F. (1989). Lymphocytic infiltration in the spinal cord of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Clin. Neuropathol. 8, 289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda H., Han S. M., Yang Y., Tong C., Lin Y. Q., Mohan K., et al. (2008). The amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 8 protein VAPB is cleaved, secreted, and acts as a ligand for Eph receptors. Cell 133, 963–977. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner B. J., Talbot K. (2008). Transgenics, toxicity and therapeutics in rodent models of mutant SOD1-mediated familial ALS. Prog. Neurobiol. 85, 94–134. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance C., Rogelj B., Hortobágyi T., De Vos K. J., Nishimura A. L., Sreedharan J., et al. (2009). Mutations in FUS, an RNA processing protein, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 6. Science 323, 1208–1211. 10.1126/science.1165942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Bosch L., Tilkin P., Lemmens G., Robberecht W. (2002). Minocycline delays disease onset and mortality in a transgenic model of ALS. Neuroreport 13, 1067–1070. 10.1097/00001756-200206120-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volonté C., Apolloni S., Skaper S. D., Burnstock G. (2012). P2X7 receptors: channels, pores and more. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 11, 705–721. 10.2174/187152712803581137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volonté C., Parisi C., Apolloni S. (2015). New kid on the block: does histamine get along with inflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 14, 677–686. 10.2174/1871527314666150225143921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton N. M., Sutter B. M., Laywell E. D., Levkoff L. H., Kearns S. M., Marshall G. P., et al. (2006). Microglia instruct subventricular zone neurogenesis. Glia 54, 815–825. 10.1002/glia.20419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Duan W., Wang W., Di W., Liu Y., Liu Y., et al. (2016). scAAV9-VEGF prolongs the survival of transgenic ALS mice by promoting activation of M2 microglia and the PI3K/Akt pathway. Brain Res. 1648, 1–10. 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. H., Fallini C., Ticozzi N., Keagle P. J., Sapp P. C., Piotrowska K., et al. (2012). Mutations in the profilin 1 gene cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 488, 499–503. 10.1038/nature11280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D. C., Ré D. B., Nagai M., Ischiropoulos H., Przedborski S. (2006). The inflammatory NADPH oxidase enzyme modulates motor neuron degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 103, 12132–12137. 10.1073/pnas.0603670103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Q., Zhao W., Beers D. R., Yen A. A., Xie W., Henkel J. S., et al. (2007). Mutant SOD1G93A microglia are more neurotoxic relative to wild-type microglia. J. Neurochem. 102, 2008–2019. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04677.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Chen S., Li X., Luo G., Li L., Le W. (2006). Neuroprotective effects of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurochem. Res. 31, 1263–1269. 10.1007/s11064-006-9166-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Danielson E. W., Qiao T., Metterville J., Brown R. H., Jr., Landers J. E., et al. (2016). Mutant PFN1 causes ALS phenotypes and progressive motor neuron degeneration in mice by a gain of toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 113, E6209–E6218. 10.1073/pnas.1605964113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E. J., Jiang J. H., Lee S. M., Yang S. C., Hwang H. S., Lee M. S., et al. (2010). Bee venom attenuates neuroinflammatory events and extends survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis models. J. Neuroinflammation 7:69. 10.1186/1742-2094-7-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiangou Y., Facer P., Durrenberger P., Chessell I. P., Naylor A., Bountra C., et al. (2006). COX-2, CB2 and P2X7-immunoreactivities are increased in activated microglial cells/macrophages of multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord. BMC Neurol. 6:12. 10.1186/1471-2377-6-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Beers D. R., Bell S., Wang J., Wen S., Baloh R. H., et al. (2015). TDP-43 activates microglia through NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome. Exp. Neurol. 273, 24–35. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Beers D. R., Henkel J. S., Zhang W., Urushitani M., Julien J. P., et al. (2010). Extracellular mutant SOD1 induces microglial-mediated motoneuron injury. Glia 58, 231–243. 10.1002/glia.20919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C., Zhang C., Zhao R., Chi S., Ge P., Zhang C. (2013). Human marrow stromal cells reduce microglial activation to protect motor neurons in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neuroinflammation 10:52. 10.1186/1742-2094-10-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Stavrovskaya I. G., Drozda M., Kim B. Y., Ona V., Li M., et al. (2002). Minocycline inhibits cytochrome c release and delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. Nature 417, 74–78. 10.1038/417074a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]