Abstract

Early childhood is a critical time for establishing food preferences and dietary habits. In order for appropriate advice to be available to parents and healthcare professionals it is essential for researchers to understand the ways in which children learn about foods. This review summarizes the literature relating to the role played by known developmental learning processes in the establishment of early eating behavior, food preferences and general knowledge about food, and identifies gaps in our knowledge that remain to be explored. A systematic literature search identified 48 papers exploring how young children learn about food from the start of complementary feeding to 36 months of age. The majority of the papers focus on evaluative components of children's learning about food, such as their food preferences, liking and acceptance. A smaller number of papers focus on other aspects of what and how children learn about food, such as a food's origins or appropriate eating contexts. The review identified papers relating to four developmental learning processes: (1) Familiarization to a food through repeated exposure to its taste, texture or appearance. This was found to be an effective technique for learning about foods, especially for children at the younger end of our age range. (2) Observational learning of food choice. Imitation of others' eating behavior was also found to play an important role in the first years of life. (3) Associative learning through flavor-nutrient and flavor-flavor learning (FFL). Although the subject of much investigation, conditioning techniques were not found to play a major role in shaping the food preferences of infants in the post-weaning and toddler periods. (4) Categorization of foods. The direct effects of the ability to categorize foods have been little studied in this age group. However, the literature suggests that what infants are willing to consume depends on their ability to recognize items on their plate as familiar exemplars of that food type.

Keywords: infant, toddler, food preference, learning, eating habits, development

Introduction

The first years of life are marked by tremendous physical and psychological developments, allowing infants to gradually become less helpless and more independent. During this period, infants show rapid advances in their language skills, social awareness, and cognitive capacity for attention and learning (Snow and McGaha, 2003; Goswami, 2008a,b). At the same time, infants undergo significant developments in the eating domain, with the transition from a complete reliance on milk, underpinned by the newborn infant's well-organized sucking reflex, to the omnivore eating behavior of the toddler. The start of this transition is the onset of weaning, when the infant is first introduced to solid foods. Complementary feeding is usually recommended to occur at around 6 months (World Health Organization, 2009; British Dietetic Association, 2016), although some suggest that weaning might begin at any time between 4 and 6 months (e.g., European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition; Agostoni et al., 2008). Regardless of such official guidelines, some parents introduce solid foods even earlier, some as early as 8 weeks of age (Caton et al., 2011). At first, children do not make their own food choices but rely on their caregivers to provide them with appropriate foods. Within 3 or 4 years, the child establishes autonomous feeding behavior, and sets boundaries on the foods they will accept (Hammer, 1992). The “food learning” journey is therefore characterized by a gradual change from total dependence on caregivers prior to weaning to the child becoming an accomplished eater, making independent food choices albeit limited by the context of what is available (Vereijken et al., 2011). The eating behaviors established during this early period track into adolescence and adulthood and, when they are healthy behaviors, may have a positive influence in combatting non-communicable diseases (Skinner et al., 2002; Vereecken et al., 2004; Coulthard et al., 2010).

Importantly, while human infants show similar affective responses toward different taste stimuli across cultures, suggesting a biological underpinning for the foods we are programmed to prefer and avoid (Mennella and Ventura, 2011), infants actually begin life with very few innate taste preferences, and a strong capacity to learn to like new foods (Davis, 1939). The environment—and the family home in particular—play a crucial role in shaping children's eating behaviors (Kral and Faith, 2007). It has been suggested that the introduction of complementary feeding is the most important time for learning about new foods, as it is during this period that the child's senses are suddenly exposed to a variety of new types of stimulation (Lipsitt et al., 1985). Cashdan (1994) found that children younger than 24 months of age were more receptive to new foods than older children, and recommended that parents should introduce new foods at this time. These suggestions support Kolb's (1984) view of the first 3 years of life as a sensitive period for the development of “perception, cognition, behaviors and experiences” in relation to food.

If the period from weaning to around 3 years of age is indeed of major importance for learning about food and developing lifelong preferences, the effective promotion of healthy eating habits in this age group would be facilitated by a better understanding of the mechanisms that support children's learning. A seminal paper by Birch and Anzman (2010) identified three learning processes relevant to children's early learning about food and eating (see also Birch and Doub, 2014). Familiarization refers to the positive impact of repeated exposure on liking of the exposed stimulus (Zajonc, 1968). Associative learning or conditioning occurs when a positive evaluation of a stimulus arises through its association with a second, already-liked stimulus (Birch and Anzman, 2010). Observational learning or social learning refers to the natural human inclination to observe and imitate the behaviors of others (Bandura, 1977). Birch and Anzman (2010; see also Birch and Doub, 2014) show that these three learning theories each play a role in young children's learning about food. Other work suggests that categorization processes—the mental grouping together of stimuli into categories and schemas (Rakison and Oakes, 2003)—also play an important role in children's learning about foods (Nguyen, 2007b). Despite the importance of this area, no systematic review has so far been conducted of the literature relating to the learning processes involved in infants' developing knowledge of food between weaning and 3 years of age. This review aims to fill this gap.

Following Kolb (1984), we consider “learning” to include developments in children's perception, cognition, behavior and experiences in relation to food. Within the target group and age range (human infants between weaning and 36 months), we include all possible aspects of what has to be learned about food. This includes amongst others:

A food's evaluative status (whether it is liked or disliked, healthy or unhealthy);

Perhaps most importantly, which foods the child will accept into their diet;

How foods are recognized based on their physical characteristics (taste, smell, texture and appearance);

The origins of foods (e.g., whether they are plant or animal products), and how they are prepared;

The names of food ingredients, preparation processes, utensils, etc.;

The contexts in which foods are eaten (appropriate times or occasions, quantities and combinations);

How foods are eaten (including oral-motor skills, regulation of food intake, mealtime etiquette);

The post-ingestive consequences of consuming foods (whether they are satiating, provide energy, cause nausea, are unsafe or inedible).

In summary, the goal of this systematic review is to provide an overview of the developmental processes that are relevant to how children learn about food. We summarize the relevant empirical evidence in relation to each process (from the start of complementary feeding to 36 months of age), and define the key gaps in the literature that need to be addressed if we are to increase our understanding of early food-related behavior.

Methodology

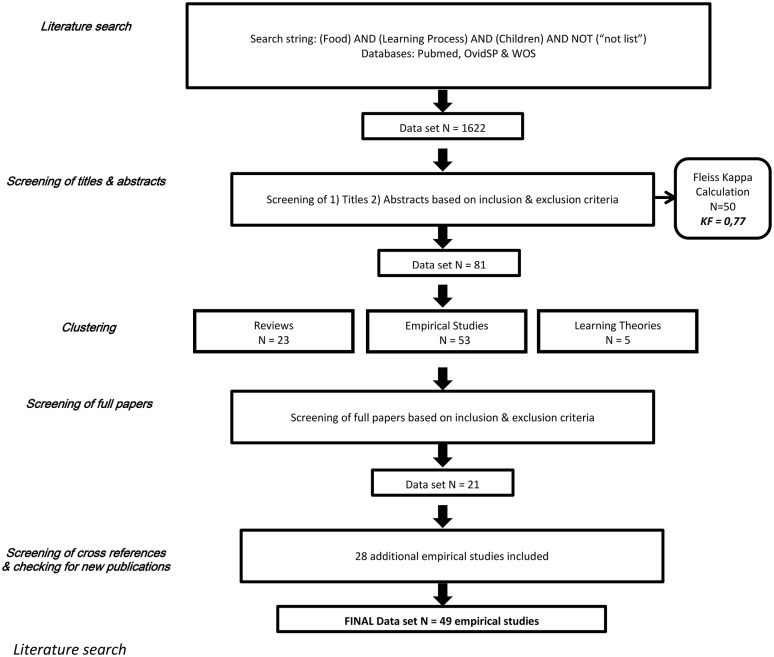

The literature search, screening and clustering methods employed in the systematic review are summarized in Figure 1 and described in more detail below.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the search and screening methods adopted in the systematic review.

Literature search

The goal of the systematic review was to identify the role played by developmental learning processes in how children learn about food from weaning to 36 months of age. Three groups of search terms were defined: one for “food,” one for “learning process” and one for “children.” For “learning process” the list of search terms included terms relating to all learning theories known to the authors. The list of keywords used as search strings can be seen in Table 1. As a preliminary search generated a large number of irrelevant articles, a “NOT list” of search terms was generated by the authors on the basis of the preliminary search (see Table 1). The search was limited to peer-reviewed articles written in English. The initial literature search was conducted first in February 2012, and then repeated in February 2016, using OvidSP, Pubmed and Web of Science. The initial search resulted in a total of 1622 papers (853 from OvidSP, 811 from Web of Science and 59 from PubMed).

Table 1.

Search strings used in the literature search.

| Search in Title and Abstract |

|---|

| Search term 1: FOOD (feed or food or eat* or taste or intake) |

| Search term 2: (AND) LEARNING (habits or socialization or socialization or enculturation or cognit* or social learning or conditioning or imitation or categorization or categorization or programming or schemas or script* or modeling or preference) |

| Search term 3: (AND) CHILDREN (baby or infant or infancy or child* or early life or toddler*) |

| (NOT) (alcohol or disorder* or teen* or allerg* or school-age* or sick or ill* or disease* or adipos* or advertis* or TV or television or adolesce* or preterm or supplement or vaccine or autism or dysphagia or defiency or policy or chimpanzee* or birth weight or colonization or rat* or sport or physical activity or cancer or carcino* or cost* or poverty or prenatal or pregnan* or HIV or education or school program or school or education program* or adult* or older or elder or elderly or subject or women or men or gender or blood concentration or plasma concentration or carries or caries or dentifrice or fluor* or disable* or fish* or vitamin D or low income or zinc or copper or nitrate or PCB) |

| (AND) Peer reviewed |

| (AND) English language |

Screening of titles and abstracts

The titles and abstracts of the articles identified by the literature search were screened by hand using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Populations

Articles addressing healthy children from weaning to 36 months old were included. Studies with fewer than five participants or involving animals were excluded, as were studies with a clinical or disease focus. Studies of food refusal, picky eating and other non-clinical “problematic” feeding behaviors were included.

Focus

Only articles relevant to a learning process in the food domain were included. Articles dealing with the pre-weaning milk-feeding period were excluded, as were studies focusing on the learning shown by parents, rather than children.

Type of article

Only articles that were published in English, with named authors, and subject to international peer review were included. Studies focusing on the development of a methodology were excluded, as were conference abstracts and position papers.

Screening involved two steps. The first step involved screening titles; this reduced the set of papers to 366. The second step involved screening of abstracts; this reduced the set of papers to 81.

Checking the reliability of screening

To check inter-rater reliability, 50 papers were randomly selected from the 366 articles remaining after the first step in the screening process. Four of the authors completed step two for these 50 papers, each making an independent judgment about their inclusion. The Fleiss's Kappa statistic (FK = 0.77) indicated an acceptable level of reliability between their judgments. Disagreements were discussed and a consensus reached in all cases. The remaining papers from step one were then assessed by the first author and a second assessor.

Clustering

To facilitate the structure of the review, papers that passed screening were clustered. Four clusters were identified, each representing a separate learning process: (1) Familiarization; (2) Observational learning; (3) Associative learning; (4) Categorization. The choice of these clusters was based on a preliminary screening of the selected papers and on the learning processes previously identified as involved in the development of eating habits (Nguyen and Murphy, 2003; Birch and Anzman, 2010).

Screening of full articles

Two authors were assigned to each of the learning theories. Both authors read all of the articles in their category and excluded any article that was deemed not relevant to how children learn about food. Articles that included participants older than 3 years were not excluded if they also included younger participants. Only reports of empirical studies were included. Screening reduced the set of relevant articles to 20.

Addition of further articles through cross-referencing and checking for new publications

Further articles were identified through their citation in the papers found in the literature search or because they cited papers found in the search. 17 additional articles were found that satisfied our inclusion/exclusion criteria. A second iteration of the literature search and screening process was conducted in February 2016, following exactly the same process as the first search; this identified 11 newly-published articles that satisfied our inclusion/exclusion criteria and these were added to the set. The final set of articles considered in the review consists of 48 papers (see Tables 2–5).

Table 2.

Summary table—studies of familiarization through repeated exposure.

| Author(s) and Year | Objectives | Country and sample | Methodology | Key findings for food learning | QA | How children learn | What is learned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahern et al., 2013 | Examine children's experience with vegetables across three European countries | UK, Denmark and France—234 children of 6–36 months | Survey assessing parental and infant familiarity, frequency of offering and liking of 56 vegetables and preparation techniques for these vegetables | UK children's liking of vegetables was related to frequency of maternal intake and frequency of offering, suggesting learning via modeling and repeated exposure. The authors conclude that increasing variety and frequency of vegetable offering between 6 and 12 months, when children are most receptive, may promote vegetable consumption in children | 10 | Observation of their mother eating a vegetable; repeated exposure to taste of vegetable | Acceptance of vegetables |

| Barends et al., 2013 | Determine the effects of repeated exposure to either vegetables or fruits on similar food acceptance at the beginning of weaning | Netherlands—101 children from 4 to 6 months old | Infants were assigned to 2 intervention groups: a vegetable group received either green bean or artichoke puree on alternate days, with two other vegetables on the other days; the fruit group received either apple or plum puree on alternate days, with two other fruits on other days, for 18 consecutive days. On day 19, the vegetable groups consumed their first fruit puree and the fruit groups their first vegetable puree | Both vegetable and fruit intake increased significantly in the vegetable group from days 1 and 2 to days 17 and 18. The fruit group consumed no more of the green beans on day 19 than the vegetable group had consumed at the 1st day of exposure. Fruit intake was significantly higher than vegetable intake from the start | 10 | Repeated exposure to the taste of new fruits or vegetables | Acceptance of the exposed fruits or vegetables |

| Beauchamp and Moran, 1984 | Examine the relationship between frequency and type of experience with sweet substances and sweet preference at birth and 6 months | USA—63 children from birth to 2 years old | Infants' taste preferences were tested at birth and 6 months with sucrose solutions of different concentrations in the following order: plain water, 0.2, 0.6, 0.6, 0.2 M sucrose. At 2 years of age, children were given a series of 3 tests, separated by at least 7 days, in which their acceptance of sweet tastes was evaluated as at birth and 6 months | At 6 months and 2 years, children who had been regularly fed sugar water consumed more of the sucrose solutions (but not more plain water) than children who had not been fed with sugar water. When tested with sucrose in a fruit-flavored drink, prior exposure to sugar water was unrelated to consumption of the sweetened or unsweetened fruit-flavored drink | 8 | Repeated exposure to a sweet taste food; formation of schema that specify a food's usual taste | Expecting and liking a specific food to have a sweet taste |

| Birch et al., 1987 | Determine the relative effectiveness of visual and taste exposure on young children's preference for novel foods | USA—43 children from 23 to 69 months | Children received either “look” or “taste” exposures to seven novel fruits. Foods were exposed 5, 10 or 15 times and one remained novel. After exposure, children were assigned to make two judgments of the 21 food pairs based either on looking or tasting, and choosing the one they liked the best | Visual exposure enhanced visual preferences and taste exposure enhanced taste preferences. The visual exposure effect disappeared when taste preference judgments of the same foods were requested. This finding is consistent with a “learned safety” interpretation of exposure effects | 10 | (a) repeated exposure to taste of new fruits (b) repeated exposure to visual appearance of new fruits | (a) liking of the taste and appearance of the fruits (b) liking of the appearance of the fruits |

| Birch et al., 1998 | Establish the number of exposures needed to increase intake of a novel target food and evaluate generalization of liking to other foods | USA—39 children from 4 to 7 months | Infants were repeatedly exposed to 1 target food (one brand of fruit or vegetable) for 10 days at home. Intake of the same food (different brand), similar food (same category), home-prepared food and different food were measured pre- and post-exposure | The greatest change in intake of the target food was observed prior to the start of the exposure phase. Repeated exposure enhanced intake only of the similar food. Post-exposure intake of the target, same and similar foods was significantly greater than intake of the different and home-prepared foods | 8 | Repeated exposure to the taste of a branded fruit or vegetable product | Acceptance of the exposed food across brands and acceptance of other similar foods |

| Blossfeld et al., 2007a | Is consumption of fruit associated with acceptance of sour taste | Ireland—53 children at 6, 12, and 18 months | Fruit intake and acceptance (measured as intake) of 4 drinks with varying degrees of sourness was measured at 6, 12, and 18 months | Children who accepted the drinks with highest sourness had better fruit acceptance at 6 and 18 months | 9 | Repeated exposure to (sour tasting?) fruit increases sour taste and fruit acceptance | Acceptance of fruit |

| Blossfeld et al., 2007b | Identify factors affecting food texture acceptance by infants | USA—70 children aged approx. 12 months | Children were exposed to cooked carrots with 2 different textures: pureed and chopped. Mothers also completed a questionnaire about the child's food habits, age of weaning, pickiness, milk feeding, the child's familiarity with textures and the frequency of exposure to novel foods | At 12 months infants consumed more pureed carrots than chopped carrots. Children with more teeth were more accepting of the chopped texture. Infants' intake of chopped carrots was predicted by previous experiences with different textures. Breast-feeding duration, food responsiveness, dietary variety and willingness to consume new foods were good predictors of intake of chopped carrots | 8 | Exposure to a variety of textures | Acceptance of a new complex texture |

| Bouhlal et al., 2014 | Compare effect of repeated exposure and flavor-flavor learning on the acceptance of a non-familiar vegetable | France—151 children 2–3 years | Toddlers were exposed 8x to 1. basic salsify puree 2. same salsify puree with extra salt 3. salsify puree as in 1 with nutmeg | Salsify intake increased from pre- to post-exposure, but no difference between groups was observed on the increase in liking of the target vegetable | 11 | Repeated exposure increases the acceptance of a non-familiar vegetable | Acceptance of a non-familiar vegetable |

| Caton et al., 2013 | Compare the effectiveness of different learning strategies | UK—72 children aged between 6 and 38 months. Also Included in Caton et al. (2014) | Children were randomly assigned to one of three conditions (repeated exposure/FFL/FNL) and were offered 10 exposures to a novel vegetable (artichoke). Pre- and post-intervention measures of artichoke puree and a control puree (carrot) intake were taken | Intake of both vegetables increased over time, with a greater increase for artichoke. Artichoke puree increased to the same extent in all three conditions, and this effect persisted for 5 weeks. Five exposures were sufficient to increase intake in the FFL/FNL conditions and 3 exposures in the repeated exposure condition | 11 | Repeated exposure to the taste of a new vegetable; no added value from associating the new vegetable with high energy content or sweet flavor | Acceptance of the new food |

| Caton et al., 2014 | Compare the effectiveness of different learning strategies | 332 children (4–38 months) in UK, Denmark and France | As Caton et al. (2013) but combined with data from similar studies in France and Denmark. The paper focuses on intake of artichoke and analyzing clusters of children | Children in the added energy condition showed the smallest change in intake over time, compared to those in the basic or sweetened artichoke condition. Contrary to expectation the FNL was less effective than RE. Another interesting insight from the paper is that the children could be clustered according to their eating behaviors into learners, plate-clearers, non-eaters and others | 11 | Repeated exposure to the taste of a new vegetable; no added value from associating the new vegetable with high energy content or with sweet flavor | Acceptance of the new food |

| Forestell and Mennella, 2007 | Evaluate the effects of breastfeeding and dietary experience on acceptance of green vegetables and fruit | USA—45 children aged between 4 and 8 months | Infants were assigned to 2 intervention groups: (1) green beans (GB), (2) GB + peach (GB-P), during an 8-day home exposure regime. Acceptance (intake, records of facial expression, rate of consumption) of green beans was evaluated on days 1 and 11, and acceptance of peach was evaluated on days 2 and 12 | Both groups tripled their intake of GB by the end of the exposure period. Children in the GB-P group showed fewer negative facial expressions during test days 11 and 12. Breastfeeding conferred no advantage for acceptance of green beans either before or after exposure | 8 | (a) repeated exposure to the taste of a new vegetable (b) repeated exposure to the taste of a fruit-vegetable combination | (a, b) acceptance of the vegetable (b) liking of the taste of both foods |

| Gerrish and Mennella, 2001 | Evaluate whether the acceptance of novel foods is facilitated by providing a variety of flavors during the weaning period | USA—48 formula-fed children with a mean age of 4.5 months | Children were assigned to 3 intervention groups: (1) pureed carrot (target vegetable), (2) pureed potatoes, (3) variety of vegetables (pureed potatoes, peas and squash), for a 9-day exposure intervention. Infants' acceptance of the target vegetable (carrot) and a novel food (chicken) was evaluated (by intake and videotape) after exposure | Groups 1 and 3 increased their intake of pureed carrot and ate more quickly. Group 3 also increased in acceptance of the novel food. Daily experience with fruits (based on an intake questionnaire) enhanced infants' initial acceptance of carrots | 8 | (a) repeated exposure to the taste of a new vegetable (b) repeated exposure to a variety of vegetables | (a,b) acceptance of the exposed vegetable (b) acceptance of a new food from a different category |

| Harris and Booth, 1987 | Explore the development of salty food preference and its link with previous exposure to dietary sodium | UK—35 children tested at 6 and 12 months | Infants were tested at 6 and 12 months of age for their preference for salt in familiar foods: unsalted and salted cereal at 6 months and unsalted and salted potatoes at 12 months. The relationship between preference for salted food and the infant's dietary experience was examined | At 6 months a positive correlation was found between preference for the salted test food and the amount of experience the child had with high-sodium foods prior to testing. At 12 months this relationship was affected by the order in which food samples were presented and the infant's familiarity with the tested food | 7 | Repeated exposure to salty foods; formation of schema that specify a food's usual taste | Liking of similar food with added salt |

| Hausner et al., 2012 | Compare the effectiveness of different learning strategies | Denmark—104 children aged between 22 and 38 months. Also Included in (Caton et al., 2014) | Children were assigned to 3 intervention groups (mere exposure/FFL/FNL) and were offered 10 exposures to a novel vegetable (artichoke). Measures of artichoke puree and carrot puree (control vegetable) intakes were taken pre- and post-intervention and at 3- and 6- months follow-up | Children's intake changed by the 5th presentation in the repeated exposure condition and by the 10th exposure in the FFL condition. Mere exposure had the largest impact on intake of unmodified puree both immediately after exposure and at the 6-month follow-up. Children in the FFL group ate more of the sweet puree. In the FNL group, no increase in intake was observed; lower amounts of carrot puree were eaten immediately after the intervention | 11 | (a) repeated exposure to the taste of a new vegetable (b) association of new vegetable with sweet flavor | (a) acceptance of exposed vegetable (b) acceptance of vegetable with added sugar |

| Heath et al., 2014 | Explore the effects of exposure to pictures of liked, disliked and unfamiliar vegetables on children's willingness to look at and taste these | UK—Study 1: 154 children aged between 19 and 26 months. Study 2—68 children aged 20–24 months | Children looked at a picture book about a target vegetable with their parents every day for 14 days, after which they took part in a visual preference test (Study 1) or taste test (Study 2), to measure their interest in looking at or eating the target vegetable vs. a matched control vegetable | Study 1: Children looked longer at pictures of the target food than at pictures of the matched control food. Study 2: Children were more easily persuaded to eat the target food than a matched control vegetable, and consumed more of the target food. In both studies, the strongest exposure effects were seen for initially unfamiliar foods | 10 | Repeated exposure to visual appearance of liked, disliked and unfamiliar vegetables | Willingness to try a novel food; acceptance of the exposed vegetable |

| Houston-Price et al., 2009 | Explore the effects of exposure to pictures of fruits and vegetables on children's willingness to taste the foods | UK—20 children aged between 21 and 24 months (mean age 23.2 months) | Children received daily exposure to either picture-book A or B (each including 2 fruits and 2 vegetables, 1 of each familiar to children) for 2 weeks. At test, children were offered the exposed and non-exposed foods to eat, and the order in which foods were tasted was recorded | Children displayed a neophobic pattern of behavior toward foods to which they had not been exposed, but not toward exposed foods. Exposure decreased children's willingness to taste familiar vegetables, but increased their willingness to taste unfamiliar fruits | 8 | Repeated exposure to visual appearance of familiar and new fruit and vegetables | Willingness to try new fruits; reluctance to try familiar vegetable |

| Lundy et al., 1998 | Determine whether food texture preferences differ between infants and toddlers and whether experience with textures influences infants' food preferences | USA—Study 1: 24 children aged between 4 and 12 months. Study 2: 12 toddlers aged from 13 to 22 months | Study (1): Infants' feeding sessions were recorded when they were offered 3 different textures of apple sauce (puree, lumpy and diced). Study (2): Toddlers were assigned to 3 intervention groups: (1) 10 days of exposure to a pureed texture followed by 10 days of exposure to a lumpy texture; (2) 20 days exposure to a lumpy texture; (3) 20 days exposure to a pureed texture | Study (1): Infants displayed more negative expressions, negative head movements and negative body movements when presented with more complex textures. Study (2): Toddlers showed more positive head and body movements and more eagerness for complex textures. Results suggest that progressive introduction to difficult-to-chew textures can facilitate acceptance of more complex textures | 8 | Progressive exposure to more complex textures | Acceptance of new complex textures |

| Maier et al., 2007 | Assess changes in acceptance of a disliked vegetable with repeated exposures and the influence of breastfeeding and mothers' eating patterns | Germany—49 children with a mean age of 7 months | Infants were offered a liked and disliked vegetable on alternate days for a 16-day period. Infants' intake and enjoyment (9-point scale) were measured. Mothers completed a questionnaire about breastfeeding practices, food neophobia, eating habits, food consumption and acceptance at 9 months | Intake of both liked and disliked vegetables increased over the 16-day exposure, with no longer significant difference between the two after the 8th exposure. Breast-fed infants ate more of the disliked vegetable on the 1st day. Infants who had mothers “high” in neophobia increased their intake of disliked vegetables more rapidly. By 9 months, 63% of the previously disliked vegetables were rated as liked | 9 | Repeated exposure to the taste of a disliked food | Acceptance and liking of an initially disliked food |

| Maier et al., 2008 | Measure the effects of breast vs. formula feeding and experience with a variety of vegetables during weaning on new food acceptance | Germany and France—147 children with a mean age of 5.2 months | Children (breast or formula-fed) were assigned to one of 3 intervention groups for a 9-day exposure phase: (1) carrots daily, (2) 3 vegetables on alternating days, (3) 3 vegetables each day. Acceptance of new foods was measured by intake and rated liking of new vegetables on the 12th and 23rd days and meat and fish several weeks later | Intake of carrots did not differ between breast- and formula-fed babies on day 1. Daily vegetable variety was more effective than the number of vegetables fed. Breastfeeding was associated with higher intake of the vegetables, but not meat or fish | 9 | Repeated exposure to a variety of vegetables | Acceptance and liking of both exposed foods and non-exposed vegetables |

| Maier-Nöth et al., 2016 | Same as Maier et al. (2008) but including follow up till 6 years | Same as Maier et al. (2008) | Same as (Maier et al., 2008) plus follow up by survey + experimental veggie liking assessment at 6 years consisting of rating 6 vegetables on a 7 pt scales and measuring ad lib eating of these 6 vegetables | At 6 years children who had been breast fed and children who had experienced high vegetable variety were more willing to taste vegetables, ate more of new vegetables and liked them more | 11 | Repeated exposure to a variety of vegetables | Acceptance and liking of both exposed foods and non-exposed vegetables |

| Mennella et al., 2008 | Explore the effects of exposure to a specific food or variety of foods on infants' acceptance of fruit and vegetables | USA—74 children aged between 4 and 9 months | Children were assigned to 2 intervention groups: (1) Pear or variety of fruits; (2) Green beans or variety of vegetables, for 8 days of home exposure, followed by a 2-day test session with pears on 1 day and green beans on the other | Eight days of dietary exposure to pears or a variety of fruits resulted in greater consumption of pears but not of green beans. Eight days of vegetable variety between and within meals led to increased acceptance of green beans, carrots and spinach. Infants exposed to only green beans or a variety of foods between meals only increased their intake of green beans | 9 | Repeated exposure to a variety of fruits or vegetables | Acceptance of new foods from the same category |

| Remy et al., 2013 | Compare the effectiveness of repeated exposure, flavor-flavor learning and flavor-nutrient learning in improving vegetable acceptance | France—95 infants aged between 5 and 7 months. Also Included in Caton et al. (2014) | Children were randomly assigned to one of 3 conditions (repeated exposure/FFL/FNL) and were offered 10 exposures to a novel vegetable (artichoke). Pre- and post-intervention measures of liking and intake of artichoke puree (target vegetable) and carrot puree (control vegetable) were collected | Intake of artichoke puree significantly increased in the RE (+63%) and FFL (+39%) groups but not in the FNL group; liking increased only in the RE group (+21%). After exposure, the RE group liked and consumed artichoke as much as they did carrot. Learning of artichoke acceptance was stable up to 3 months post-exposure | 10 | Repeated exposure to the taste of a new vegetable; association of a food with a liked taste | Acceptance of the new food |

| Sullivan and Birch, 1994 | Examine the effects of dietary experience and milk feeding regimen on acceptance of first vegetables | USA—36 children aged between 4 and 6 months | Infants were assigned to be fed salted or unsalted vegetables at home every day for a 10-day period. Infant intake of the target vegetable and video-recorded responses to this were measured before, during, after the intervention and at a 10-day follow-up. Intake of chicken or tofu was also measured before and after the exposure period | Infants increased in acceptance and liking of the novel vegetable in both forms, regardless of which version they had been exposed to. Breastfed infants increased their intake to a greater extent than formula-fed infants; consumption of breastmilk during exposure and vegetable intake after exposure were positively correlated | 9 | Repeated exposure to a vegetable with added salt | Acceptance of vegetable with or without added salt liking of the vegetable with or without added salt |

| de Wild et al., 2013 | Investigate the efficacy of flavor-nutrient learning for improving intake of novel vegetables | Netherlands—40 children aged between 2 and 4 years (mean age 36 month) | Children were assigned to 2 intervention groups: group 1 received a high-energy variant of one soup (e.g., HE spinach) and a low energy variant of the other (LE endive); for group 2 the pairing was reversed (HE endive, LE spinach). Children consumed the vegetable soups (endive and spinach) twice a week for 7 weeks | An increase in ad lib intake of both vegetables soups was observed, irrespective of the energy content. Children showed a significant increase in liking of the vegetable soup consistently paired with high energy, supporting FNL | 11 | (a) repeated exposure to the taste of a vegetable soup (b) association of vegetable soup with energy content | (a) acceptance of the exposed food (b) liking of the vegetable paired with high energy content |

Table 5.

Summary table—studies of learning through categorization.

| Author(s) and Year | Objectives | Country and sample | Methodology | Key findings for food learning | QA | How children learn | What is learned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beauchamp and Moran, 1984 | Examine the relationship between frequency and type of experience with sweet substances and sweet preference at birth and 6 months | USA—63 children from birth to 2 years old | Infants' taste preferences were tested at birth and 6 months with sucrose solutions of different concentrations in the following order: plain water, 0.2, 0.6, 0.6, 0.2 M sucrose. At 2 years of age, children were given a series of 3 tests, separated by at least 7 days, in which their acceptance of sweet tastes was evaluated as at birth and 6 months | At 6 months and 2 years, children who had been regularly fed sugar water consumed more of the sucrose solutions (but not more plain water) than children who had not been fed with sugar water. When tested with sucrose in a fruit-flavored drink, prior exposure to sugar water was unrelated to consumption of the sweetened or unsweetened fruit-flavored drink | 8 | Repeated exposure to a sweet taste food; formation of schema that specify a food's usual taste | Expecting and liking a specific food to have a sweet taste |

| Brown and Harris, 2012b | Understand how previously liked foods become rejected | UK—Study 1: 312 children aged 6–57 months. Study 2: 89 children aged 12–56 months | Study 1: Parents completed a questionnaire on children's rejection of previously accepted foods. Study 2: Parents completed a questionnaire on children's rejection of previously accepted foods, picky eating and food neophobia | 74% (Study 1) and 49% (Study 2) of parents reported at least 1 occurrence of their child rejecting previously accepted foods (PAF), typically vegetables, mixed foods, fruits, brown foods and foods of mixed color. Study 2: Rejection of PAF was related to pickiness and food neophobia. Findings suggest that changes in form and color of PAF may elicit a neophobic response | 9 | Formation of schemas that specify the food's usual form and color | Rejection of foods that have an unusual appearance |

| Cashdan, 1998 | Investigate food habits and aversions in children as potentially adaptive behaviors | USA—129 children from birth to 10 years | Parents (mostly mothers) filled in a questionnaire in which they retrospectively described their child's eating behavior at different ages | Some foods refused by children obscured the food's identity (e.g., foods in sauces, mixed foods, pureed items). 52% of toddlers preferred to eat foods separately rather than mixed; only 3% preferred mixtures of foods | 6 | Formation of schemas that specify the food's usual form and color | Rejection of foods that have an unusual appearance |

| Harris and Booth, 1987 | Explore the development of salty food preference and its link with previous exposure to dietary sodium | UK—35 children tested at 6 and 12 months | Infants were tested at 6 and 12 months of age for their preference for salt in familiar foods: unsalted and salted cereal at 6 months and unsalted and salted potatoes at 12 months. The relationship between preference for salted food and the infant's dietary experience was examined | At 6 months a positive correlation was found between preference for the salted test food and the amount of experience the child had with high-sodium foods prior to testing. At 12 months this relationship was affected by the order in which food samples were presented and the infant's familiarity with the tested food | 7 | Repeated exposure to salty foods; formation of schema that specify a food's usual taste | Liking of similar food with added salt |

| Macario, 1991 | Explore children's knowledge of the predictive validity of color in determining food category membership | USA—12 children aged between 2.7 and 3.5 years | Children were asked to identify which of a pair of (identical except for color) food or non-food exemplars was the appropriate color. Production and comprehension of color labels was also tested | Children discriminated the appropriately colored items at above chance levels, for both foods and non-foods; younger children named colors less well. Preliminary evidence was found for a relationship between color name knowledge and the ability to recognize a food as inappropriately colored | 7 | Formation of schemas that specify the food's usual color | Usual appearance of familiar foods |

| Nguyen, 2007b | Explore children's ability to classify items (including foods) into script and taxonomic categories | USA—14 children aged between 2.2 and 3.0 years (mean age 2.6 years) | Matching task (“which is the same kind of thing?”) with a choice of 2 items to match to target. Targets came from a range of categories, including foods | Children were able to classify and cross-classify foods into taxonomic (e.g., fruits) and script (e.g., breakfast foods) categories | 9 | Formation of taxonomic and script categories that specify the food's type and situations in which it is eaten | Awareness of which foods are appropriate to eat in which combinations or situations |

| Rozin et al., 1986 | Explore when children learn what not to eat, i.e., disgusting, dangerous and inappropriate items, and unacceptable combinations of foods | USA—54 children aged between 16 months and 5 years | Children were offered a series of 33 snacks or dinner time foods, inedible, disgusting or dangerous items, or inappropriate combinations of foods to taste; contact with each food was recorded | Children accepted a large number of foods deemed disgusting, dangerous or inappropriate by adults; acceptance of these decreased with age, especially between 16–29 months and 30–42 months; unusual combinations of foods remained acceptable up to 5 years of age | 9 | Formation of schemas for foods and non-food items | Rejection of inappropriate items as non-foods |

| Shutts et al., 2009 | Establish whether infants categorize foods by substance rather than shape, as do adults and older children, and therefore whether food constitutes a core knowledge system | USA—Study 2: 40 children aged 9 months. Study 3: 20 children aged 9 months. Studies 4, 5 and 6: 32 children aged 8 months. Study 7: 16 children aged 8 months | Study (2): Infants' looking times were measured toward a display of 2 food items lying on top of each other; when the top item was grasped, either only that item or both items were lifted together. Study (3): as (2), except that two halves of a single food were shown. Studies (4-7): Infants were habituated to an experimenter tasting a food in a specific form and container; test trials showed the habituated stimulus vs. novel food/container/form combinations | Study (2): Infants showed no preference for two foods moving as one or separately; (3): Infants looked longer when single foods broke in two; (4): Infants discriminated changes in food and container; (5): Infants dishabituated equally to changes in food and container; (6 and 7): Infants dishabituated equally to changes in food's color/texture and shape. Overall, there was no evidence that infants treat foods differently to non-foods at 9 months | 11 | Formation of schemas for foods and non-food items | Characteristics of foods that are important to attend to—color and texture, rather than shape or container |

| Wertz and Wynn, 2014 | To examine whether infants identify plants and artifacts as a food source after seeing an adult place these in their mouth | USA—Exp 1: 32 infants aged 18 months. Exp 2: 16 infants aged 18–19 months. Exp 3: 16 infants aged 18 months. Exp 4: 32 infants aged 6 months | Exp 1: infants observed experimenters place a dried fruit attached to a plant or an artifact either in their mouth (food-relevant action) or behind their ear (food-irrelevant action). Fruits were then placed on a tray and infants were asked “which foods can you eat?” in the in-mouth condition or “which foods can you use?” in the behind-ear condition. Exp 2: As in Exp 1 but infants were exposed to in-mouth actions of a fruit from a plant or a more familiar artifact. Exp 3: Infants were exposed only to fruits hanging from a plant or from an artifact. Exp 4: In a violation of expectation paradigm, infants were exposed to the in-mouth action for fruits attached to a plant vs. an artifact | After observing an adult place a food from a plant or artifact in their mouth, 6- to 18-month-old infants are more likely to identify the plant as a food source than the artifact | 10 | (a) observational learning of food sources is selective (b) learning about food sources depends on categorization of source as edible | Acceptance of item as edible |

Table 3.

Summary table—studies of learning through associative principles.

| Author(s) and Year | Objectives | Country and sample | Methodology | Key findings for food learning | QA | How children learn | What is learned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bouhlal et al., 2014 | Compare effect of repeated exposure and flavor-flavor learning on the acceptance of a non-familiar vegetable | France—151 children 2–3 years | Toddlers were exposed 8x to 1. basic salsify puree 2. same salsify puree with extra salt 3. salsify puree as in 1 with nutmeg | Salsify intake increased from pre- to post-exposure, but no difference between groups was observed on the increase in liking of the target vegetable | 11 | Repeated exposure increases the acceptance of a non-familiar vegetable | Acceptance of a non-familiar vegetable |

| Brown and Harris, 2012a | Examine whether disliked foods can act as contaminants to liked foods during infancy | UK—18 children aged 18–26 months (mean age 22 months) | Children were offered a liked food that was touching a disliked food. Their response to this liked food was compared to the responses of a control group | Children were less likely to eat a liked food touching a disliked food. Disliked foods can act as contaminants, suggesting that they may be perceived as disgusting by children | 7 | Association of a liked food with a disliked food | Rejection of the liked food |

| Caton et al., 2013 | Compare the effectiveness of different learning strategies | UK—72 children aged between 6 and 38 months | Children were randomly assigned to one of three conditions (repeated exposure/FFL/FNL) and were offered 10 exposures to a novel vegetable (artichoke). Pre- and post-intervention measures of artichoke puree and a control puree (carrot) intake were taken | Intake of both vegetables increased over time, with a greater increase for artichoke. Artichoke puree increased to the same extent in all three conditions, and this effect persisted for 5 weeks. Five exposures were sufficient to increase intake in the FFL/FNL conditions and 3 exposures in the repeated exposure condition | 11 | Repeated exposure to the taste of a new vegetable; no added value from associating the new vegetable with high energy content or sweet flavor | Acceptance of the new food |

| Caton et al., 2014 | Compare the effectiveness of different learning strategies | 332 children (4–38 months) in UK, Denmark and France | As Caton et al., 2013 but combined with data from similar studies in France and Denmark. The paper focuses on intake of artichoke and analyzing clusters of children | Children in the added energy condition showed the smallest change in intake over time, compared to those in the basic or sweetened artichoke condition. Contrary to expectation the FNL was less effective than RE. Another interesting insight from the paper is that the children could be clustered according to their eating behaviors into learners, plate-clearers, non-eaters and others | 11 | Repeated exposure to the taste of a new vegetable; no added value from associating the new vegetable with high energy content or with sweet flavor | Acceptance of the new food |

| Coyle et al., 2000 | Evaluate whether pavlovian conditioning methods can be used to increase ingestion of non-preferred solutions | USA—24 formula-fed children aged between 4 and 7 months | During a 3-day olfactory conditioning period, parents placed a scented disk on the rim of their infants' formula bottle at every feeding. Infants' responses to water were tested when their water bottles were scented with: training odor, novel odor or no odor during 3 consecutive trials | Infants sucked more frequently and consumed significantly more water when tested with the training odor than when tested with no odor | 7 | Association of a new food with a flavor previously paired with a liked food | Acceptance of the new food |

| Forestell and Mennella, 2007 | Evaluate the effects of breastfeeding and dietary experience on acceptance of green vegetables and fruit | USA—45 children aged between 4 and 8 months | Infants were assigned to 2 intervention groups: (1) green beans (GB), (2) GB + peach (GB-P), during an 8-day home exposure regime. Acceptance (intake, records of facial expression, rate of consumption) of green beans was evaluated on days 1 and 11, and acceptance of peach was evaluated on days 2 and 12 | Both groups tripled their intake of GB by the end of the exposure period. Children in the GB-P group showed fewer negative facial expressions during test days 11 and 12. Breastfeeding conferred no advantage for acceptance of green beans either before or after exposure | 8 | (a) repeated exposure to the taste of a new vegetable (b) repeated exposure to the taste of a fruit-vegetable combination | (a, b) acceptance of the vegetable (b) liking of the taste of both foods |

| Gregory et al., 2010 | Explore the association between feeding practices and children's eating behavior | Australia—156 children aged between 2 and 4 years (mean age 3.3 years) | Mothers completed questionnaires about maternal feeding practices, child eating behavior and reported their child's height and weight. The questionnaire was repeated 12 months later | Modeling of healthy eating predicted lower child food fussiness and higher interest in food 1 year later, and pressure to eat predicted lower child interest in food. Restriction did not predict changes in child eating behavior. Maternal feeding practices did not prospectively predict child food responsiveness or child BMI | 10 | (a) observation of adult model eating healthy (b) association of foods/eating with parental pressure to eat | (a) enjoyment of eating and willingness to try new foods (these are aspects of fussy eating) (b) lower interest in food |

| Hausner et al., 2012 | Compare the effectiveness of different learning strategies | Denmark—104 children aged between 22 and 38 months | Children were assigned to 3 intervention groups (mere exposure / FFL/ FNL) and were offered 10 exposures to a novel vegetable (artichoke). Measures of artichoke puree and carrot puree (control vegetable) intakes were taken pre- and post-intervention and at 3- and 6- months follow-up | Children's intake changed by the 5th presentation in the repeated exposure condition and by the 10th exposure in the FFL condition. Mere exposure had the largest impact on intake of unmodified puree both immediately after exposure and at the 6-month follow-up. Children in the FFL group ate more of the sweet puree. In the FNL group, no increase in intake was observed; lower amounts of carrot puree were eaten immediately after the intervention | 11 | (a) repeated exposure to the taste of a new vegetable (b) association of new vegetable with sweet flavor | (a) acceptance of exposed vegetable (b) acceptance of vegetable with added sugar |

| Johnson et al., 1991 | Assess the conditioning effect of an energy-dense food and the capacity of the child to adjust his/her intake accordingly | USA—20 children aged between 2 and 5 years | Children consumed a fixed quantity of novel-flavored yogurts that were high or low in fat every day for 8 days | Children increased their preference for the flavor paired with the energy-dense yogurt | 7 | Association of new flavor with energy content | Liking of the flavor paired with high energy content |

| Remy et al., 2013 | Compare the effectiveness of repeated exposure, flavor-flavor learning and flavor-nutrient learning in improving vegetable acceptance | France—95 infants aged between 5 and 7 months | Children were randomly assigned to one of 3 conditions (repeated exposure/FFL/FNL) and were offered 10 exposures to a novel vegetable (artichoke). Pre- and post-intervention measures of liking and intake of artichoke puree (target vegetable) and carrot puree (control vegetable) were collected | Intake of artichoke puree significantly increased in the RE (+63%) and FFL (+39%) groups but not in the FNL group; liking increased only in the RE group (+21%). After exposure, the RE group liked and consumed artichoke as much as they did carrot. Learning of artichoke acceptance was stable up to 3 months post-exposure | 10 | Repeated exposure to the taste of a new vegetable association of a food with a liked taste | Acceptance of the new food |

| Vereecken et al., 2004 | Examine differences in mothers' food parenting practices by educational level and their relationship with preschoolers' food consumption | Belgium—316 mother-child pairs, children aged between 2.5 and 7 years (mean age 4.7 years) | Mothers completed a questionnaire covering frequency of food consumption, parenting practices and mothers' educational level. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to identify variables that predict the consumption of fruits/vegetables/sweets/soft drinks | Mothers' own consumption was an independent predictor of intake of the 4 selected foods; verbal praise predicted children's vegetable consumption; permissiveness predicted regular consumption of soft drinks and sweets; use of food as a reward predicted regular sweet consumption. Differences in children's food consumption by mothers' educational level were completely explained by mother's consumption and other food parenting practices for fruit and vegetables but not for soft drinks | 9 | (a) observation of mother as eating model for specific foods (b) association of vegetable consumption with verbal praise | (a) acceptance of foods eaten by mother (b) acceptance of foods that lead to praise |

| de Wild et al., 2013 | Investigate the efficacy of flavor-nutrient learning for improving intake of novel vegetables | Netherlands—40 children aged between 2 and 4 years (mean age 36 month) | Children were assigned to 2 intervention groups: group 1 received a high-energy variant of one soup (e.g., HE spinach) and a low energy variant of the other (LE endive); for group 2 the pairing was reversed (HE endive, LE spinach). Children consumed the vegetable soups (endive and spinach) twice a week for 7 weeks | An increase in ad lib intake of both vegetables soups was observed, irrespective of the energy content. Children showed a significant increase in liking of the vegetable soup consistently paired with high energy, supporting FNL | 11 | (a) repeated exposure to the taste of a vegetable soup (b) association of vegetable soup with energy content | (a) acceptance of the exposed food (b) liking of the vegetable paired with high energy content |

Table 4.

Summary table—studies of learning through observation.

| Author(s) and Year | Objectives | Country and sample | Methodology | Key findings for food learning | QA | How children learn | What is learned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addessi et al., 2005 | Determine whether the effect of modeling on the acceptance of a novel food is food specific | USA—27 children from 2 to 5 years (mean age 3.9 years) | Children were assigned to one of 3 intervention groups: Presence (a model was present but not eating the food), Different food (model and child ate different foods), Same food (model and child ate the same foods) | Children in the “same food” condition ate more of the novel food than those in the “presence” and “different food” conditions. Children's ages (below or above 45 months), early feeding practices and classroom membership did not affect food acceptance | 7 | Observation of an adult model eating a new food | Acceptance of the same food |

| Ahern et al., 2013 | Examine children's experience with vegetables across three European countries | UK, Denmark and France—234 children of 6–36 months | Survey assessing parental and infant familiarity, frequency of offering and liking of 56 vegetables and preparation techniques for these vegetables | UK children's liking of vegetables was related to frequency of maternal intake and frequency of offering, suggesting learning via modeling and repeated exposure. The authors conclude that increasing variety and frequency of vegetable offering between 6 and 12 months, when children are most receptive, may promote vegetable consumption in children | 10 | Observation of their mother eating a vegetable repeated exposure to taste of vegetable | Acceptance of vegetables |

| Ashman et al., 2014 | Does fruit and vegetable consumption affect fruit and vegetable consumption of off-spring? | Australia—52 pregnant women and their children till 2–3 years | Dietary intake was measured based on food frequency questionnaires, followed by correlation and mediation analysis | Effect of maternal diet during pregnancy on fruit and vegetable intake by their children was mediated through matermal post-natal diet. This supports the role of the mother's current diet on the diet quality of their children at 2–3 years and supports literature that shows that mothers can act as role models for their children by consuming a wide variety of nutritious foods | 10 | Observation of mothers consuming nutritious foods | Acceptance of nutritious foods esp. fruit and vegetables |

| Birch, 1980 | Investigate the influence of peer models' food selection and eating behaviors on preschoolers' food preferences | USA—39 children from 2 to 4 years (mean age 3.1 years) | A (target) child who preferred vegetable A to B was seated with 3 or 4 peers with opposite preference patterns. Children were served their preferred and non-preferred vegetable pairs at lunch and asked to choose one. On day 1 the target child chose first, while on days 2, 3, and 4 peers chose first | 70% of the children showed a shift from choosing their preferred food on day 1 to choosing their non-preferred food by day 4. Consumption data corroborated these results. In the post-intervention test fewer than half of the peers changed their preferred foods. Younger children were more affected by peer modeling than older children | 9 | Observation of a child role model eating a non-preferred food | Liking and acceptance of previously disliked food |

| Edelson et al., 2016 | Evaluate how parents' prompts to eat fruits and vegetables are related to children's intake of these foods | USA—60 families with toddlers of 12–36 months | Food diary and video to record child and parent behavior; after 1 week, video recording when child was given a novel fruit or vegetable; after 3 months three 24 h dietary recalls | The most immediately successful prompt for regular meals across food types was modeling. There was a trend for using another food as a reward to work less well than a neutral prompt for encouraging children to try a novel fruit or vegetable | 11 | Observation of an adult model eating a fruit or vegetable | Acceptance of fruits and vegetables |

| Gregory et al., 2010 | Explore the association between feeding practices and children's eating behavior | Australia—156 children aged between 2 and 4 years (mean age 3.3 years) | Mothers completed questionnaires about maternal feeding practices, child eating behavior and reported their child's height and weight. The questionnaire was repeated 12 months later | Modeling of healthy eating predicted lower child food fussiness and higher interest in food 1 year later, and pressure to eat predicted lower child interest in food. Restriction did not predict changes in child eating behavior. Maternal feeding practices did not prospectively predict child food responsiveness or child BMI | 10 | (a) observation of adult model eating healthy (b) association of foods/eating with parental pressure to eat | (a) enjoyment of eating and willingness to try new foods (these are the aspects of fussy eating) (b) lower interest in food |

| Hamlin and Wynn, 2012 | Investigate whether a source's previous pro/antisocial behavior influences imitation of food preferences | USA—48 infants aged 15–16 months | Infants were assigned to one of three conditions (prosocial, novel or antisocial), and exposed to a puppet show where either pro- or anti-social behavior was displayed. During the show the same puppet (or a novel puppet) revealed their favorite food. Following the show infants took part in a food preference test | When presented with a puppet who had demonstrated novel or prosocial behavior, infants chose the food for which the puppet expressed a preference. This effect was not observed for puppets who demonstrated antisocial behavior | 11 | Selective observational learning, based on an infant's evaluation of the individual's behavior | Acceptance of a food liked by models demonstrating prosocial or novel behavior |

| Harper and Sanders, 1975 | Determine the impact of adults offering and/or modeling eating of unfamiliar foods to children in the home | USA—80 children aged between 14 and 48 months | Children were assigned to 3 intervention groups: (1) “offer-only condition,” (2) “adult-also-eats condition,” (3) “male/female visitor offer-only condition.” Children were offered 2 new foods at home | Children accepted the food item offered more often when adults were also eating, especially girls. Foods were more often accepted more when presented by the mother than by a visitor, especially by children at the younger end of the age range | 8 | Observation of an adult model (especially the mother) eating a novel food | Willingness to try a novel food |

| Lumeng and Hillman, 2007 | Investigate the effect of group size on food intake | USA—54 children aged between 2.5 and 6.5 years | Children took part in two conditions; small group (n = 3) and large groups (n = 9. Food intake (g) and duration of snack session were recorded | Children consumed approx. 30% more food when eating in a large group compared to a small group if the snack duration was longer than 11.4 min. No group differences in intake were observed when snack duration was shorter than this | 10 | Social facilitation of eating when among larger groups | Greater acceptance of snack foods |

| McGowan et al., 2012 | Identify environmental and personal factors predicting intake of core and non-core foods by young children | UK—434 pre-school children (2–5 years) | Self-report survey among caregivers and multiple regression analysis | Only parental intake was important across all types of foods (fruits, vegetables and non-core foods), whereas feeding styles, children's preferences and availability were relevant for selected foods only | 11 | Observation of a parent eating | Acceptance of foods eaten by the parent(s) |

| Morton et al., 1996 | Evaluate the eating habits of children between 2 and 3 years of age | Australia—27 children aged between 2 and 3 years | Mothers answered a questionnaire consisting of 32 open-ended questions and a 24-h diet recall for their child | Most mothers reported that their 2-year-old children ate the same foods as the rest of the household. Children were encouraged to eat the foods that were offered to them by seeing parents or siblings as role models. Mothers reported that their children would readily imitate the example of their older siblings | 3 | Observation of an adult or sibling eating | Acceptance of foods eaten by the role model |

| Pliner and Pelchat, 1986 | Evaluate the similarities in food preferences between children, their siblings and parents | Canada—55 families with a child aged between 24 and 83 months | Survey of food preferences of the target child, mother, father and sibling. The likes/dislikes of the target children were cross-tabulated with those of their family and Φ-statistics were computed for the child-mother, child-father and child-sibling pairs as measures of similarity in food preferences | Children's food preferences were more similar to those of members of their own family than to those of members of pseudo families (families from same subcultural group and with a child in the target age group). Children more closely resembled siblings in their real and pseudo families than mothers or fathers. The target children's preferences resembled those of their (real) siblings most strongly | 7 | Observation of family members as eating models | Liking of the foods liked by other family members |

| Skinner et al., 1998 | Determine the concordance between the food preferences of toddlers and their family members | USA—118 children aged between 28 and 36 months | Mothers, fathers and an older sibling completed a questionnaire about 196 foods commonly eaten across the US. Response categories were: never offered, never tasted, likes and eats, dislikes but eats, likes but does not eat, and dislikes and does not eat | The concordance between mother/child pairs for liked foods was high (78%), while for disliked foods it was very low (4%). Overall, concordance between child/mother, child/father and child/sibling were very high, with no family member more influential than another. 25% of the food items were liked and eaten by at least 85% of children | 9 | Observation of family members as eating models | Liking of the foods that are liked by other family members |

| Skinner et al., 2002 | Explore changes in children's food preferences with age and identify influences on these | USA—70 child/mother pairs monitored from 2 to 8 years of age | Mothers completed the Food Preference Questionnaire for children when they were 2 or 3 (T1), 4 (T2) and 8 (T3) years of age, and for themselves at T1 and T3. Changes in food preferences were explored | Mothers reported that, on average, children liked 60% of the 196 foods at T1. This number increased by a non-significant 3.7% during the 5.7 years of the study. The number of foods liked at 4 years of age was the strongest predictor of the foods liked at 8 years and the child's food neophobia score. Mothers tended not to offer their child foods they disliked themselves | 11 | Observation of the mother as eating model for specific foods | Liking of the same foods as the mother |

| Vereecken et al., 2004 | Examine differences in mothers' food parenting practices by educational level and their relationship with preschoolers' food consumption | Belgium—316 mother-child pairs, children aged between 2.5 and 7 years (mean age 4.7 years) | Mothers completed a questionnaire covering frequency of food consumption, parenting practices and mothers' educational level. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to identify variables that predict the consumption of fruits/vegetables/sweets/soft drinks | Mothers' own consumption was an independent predictor of intake of the 4 selected foods; verbal praise predicted children's vegetable consumption; permissiveness predicted regular consumption of soft drinks and sweets; use of food as a reward predicted regular sweet consumption. Differences in children's food consumption by mothers' educational level were completely explained by mother's consumption and other food parenting practices for fruit and vegetables but not for soft drinks | 9 | (a) observation of mother as eating model for specific foods (b) association of vegetable consumption with verbal praise | (a) acceptance of foods eaten by mother (b) acceptance of foods that lead to praise |

| Wardle et al., 2005 | Investigate the association between parental control, child food neophobia and child fruit/vegetable consumption | England—564 children aged between 24 and 72 months (mean age of 45.2 months) | Parents completed a questionnaire with items assessing parents' and children's fruit and vegetable intake, the Parental Control Index, and the Child Food Neophobia Scale | Child fruit and vegetable consumption was positively correlated with parental fruit and vegetable consumption and negatively correlated with child neophobia. No relationship was found with parental control when parental intake and neophobia were controlled for | 11 | (a) observation of parents as models for eating specific foods | (a) liking of same foods as parents |

| Wertz and Wynn, 2014 | To examine whether infants identify plants and artifacts as a food source after seeing an adult place these in their mouth | USA—Exp 1: 32 infants aged 18 months. Exp 2: 16 infants aged 18–19 months. Exp 3: 16 infants aged 18 months. Exp 4: 32 infants aged 6 months | Exp 1: infants observed experimenters place a dried fruit attached to a plant or an artifact either in their mouth (food-relevant action) or behind their ear (food-irrelevant action). Fruits were then placed on a tray and infants were asked “which foods can you eat?” in the in-mouth condition or “which foods can you use?” in the behind-ear condition. Exp 2: As in Exp 1 but infants were exposed to in-mouth actions of a fruit from a plant or a more familiar artifact. Exp 3: Infants were exposed only to fruits hanging from a plant or from an artifact. Exp 4: In a violation of expectation paradigm, infants were exposed to the in-mouth action for fruits attached to a plant vs. an artifact | After observing an adult place a food from a plant or artifact in their mouth, 6- to 18-month-old infants are more likely to identify the plant as a food source than the artifact | 10 | (a) observational learning of food sources is selective (b) learning about food sources depends on categorization of source as edible | Acceptance of item as edible |

Quality assessment

Articles were assessed for quality using assessment criteria adapted from Jackson et al. (2008). Quality criteria were based on whether the article provided a clear description/explanation of: (1) the design; (2) the scientific background and rationale; (3) the hypotheses and objectives; (4) the sample; (5) the data analysis; (6) the findings in relation to the hypotheses and objectives; (7) the provision of attrition/exclusion data, and appropriate handling of missing data; (8) the appropriateness of the procedure; (9) consideration of methodological strengths; (10) consideration of the limits of the study; and (11) the study's relevance for theories of learning about food. As such quality criteria are necessarily subjective we used them only to exclude low-scoring outliers in terms of the total scores awarded. Two authors independently rated each paper and discussed any disagreements until consensus was reached. Quality assessment (QA) scores ranged from 3 to 11 (out of a maximum of 11); 48 papers were awarded scores of 6 or higher, satisfying the majority of the rated criteria. One paper received an outlying score of 3 and was excluded from further consideration. Quality assessment (QA) ratings are provided in Tables 2–5, which list the articles relevant to each of the learning theories of interest.

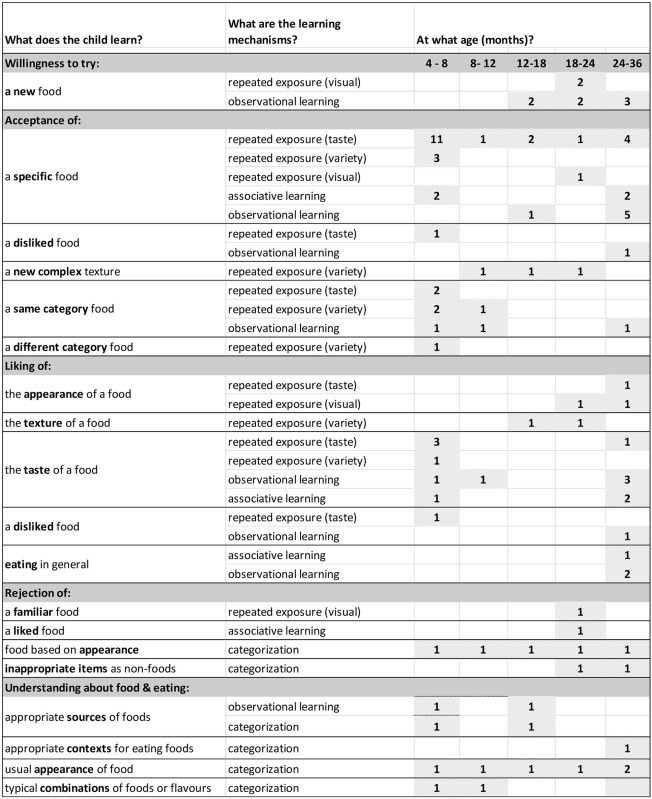

Summary of literature

The 48 papers that met the quality assessment criteria were grouped according to the learning process(es) they addressed: 24 papers described studies involving familiarization, 12 explored the role of associative learning, 17 reported studies of observational learning and 9 examined the role played by categorization. This fourteen papers investigated more than one learning process. In the following sections, we introduce each identified learning process, summarize the findings of the papers of relevance to it, and highlight gaps in knowledge remaining to be explored.

Familiarization through exposure

Familiarization to a stimulus through repeated exposure can increase liking of it. Thus, familiarization with the taste of a previously disliked or unfamiliar food can lead to increased liking and intake. The powerful influence of familiarity begins at the very earliest stages of life, when infants ingest flavors while in utero and during milk feeding (Mennella et al., 2009; Nehring et al., 2015), and continues into adulthood (Zajonc, 1968). Here we focus on the effects of exposure to specific tastes or foods from the beginning of weaning to 36 months of age. There are several theoretical perspectives on the mechanism that underpins this effect. According to Zajonc, repeated presentation of a stimulus causes a shift in affect toward it. Thus, familiarized foods take on a more positive valence and are simply liked more. Kalat and Rozin (1973) alternatively offer a “learned safety hypothesis,” according to which repeated exposure teaches us that ingestion of a food is not associated with negative consequences and, thereby, that it is safe to eat.

Twenty-four studies have explored the effects of repeated exposure to food in children between the time of weaning and 36 months. One article (Caton et al., 2014) reports a meta-analysis of 3 separate studies (Hausner et al., 2012; Caton et al., 2013; Remy et al., 2013). Findings originate from the UK, USA, Netherlands, Denmark, France, Ireland and Germany. The mean quality assessment score for these papers was 9.3 (range 7–11), indicating that research conducted in this area is generally of high quality. The 24 studies provided exposure in one of four ways: exposure to specific tastes or foods; exposure to a variety of food types; exposure to a variety of food textures; or exposure to a food's appearance.

Exposure to specific tastes or foods

The literature confirms that the tastes infants are exposed to at an early age have long-lasting effects on their liking of specific tastes. Beauchamp and Moran (1984) investigated the effects of early exposure to water containing sugar on later acceptance of sweetened water. Infants who were repeatedly exposed to sugar water at 3 months of age showed increased acceptance of sugar water relative to plain water at 2 years of age compared to those who had never tasted it. Harris and Booth (1987) reported that, by 6 months of age most infants have a preference for salty foods, but the strength of this preference was related to the number of times the child had consumed salty foods during the previous week. Interestingly, 12-month-old infants showed no relationship between their preference for salty foods and their recent consumption of these. By this age infants preferred foods to be salty only if that food type usually contained added salt, suggesting that familiarity with specific food-flavor combinations becomes more important with age. Blossfeld et al. (2007a) also reported that exposure to specific tastes early in life is associated with later taste preferences. While sour tastes are generally rejected by infants and young children (Desor et al., 1975; Steiner, 1977), Blossfeld et al. found that some 18-month-old children accepted sour-tasting solutions, and that these children reportedly had higher intake of fruit post-weaning.

Repeated exposure has also been demonstrated to be effective in encouraging infants to consume more of a target food during the weaning period. Sullivan and Birch (1994) reported increased intake of an unfamiliar vegetable (peas or green beans) by 4- to 6-month-old infants after 10 taste exposures to the vegetable. Forestell and Mennella (2007) confirmed that consumption of green beans by 4- to 8-month-olds tripled after 8 days of exposure, while Birch et al. (1998) demonstrated that a single exposure was sufficient to increase intake in infants of this age. Maier et al. (2007) showed that repeated exposure can also increase infants' intake of an initially disliked food. Eight exposures to a disliked vegetable were sufficient to increase intake in 7-month-olds, an effect that was sustained for at least 9 months in two-thirds of the children. More recently, Remy et al. (2013) found that 10 exposures to a new vegetable during weaning increased infants' intake of the food both in the short term and up to 6 months later.

Several studies have shown repeated exposure to a new food to increase intake in infants and toddlers beyond the weaning period. Bouhlal et al. (2014) found that exposing 2- to 3-year-old children to salsify 10 times increased intake of this vegetable, while de Wild et al. (2013) demonstrated that repeated tasting of an unfamiliar vegetable soup (endive) increased intake compared to baseline in children aged 2–5 years. The effects of repeated exposure can also be long-lasting at this age. Five to ten exposures to the taste of an unfamiliar vegetable have been shown to increase intake at 2 weeks (Caton et al., 2013, 2014) or even 6 months (Hausner et al., 2012) after the intervention. The survey study by Ahern et al. (2013) supports this body of evidence in demonstrating that repeated exposure leads to greater liking of vegetables.

Exposure to a variety of foods

Exposing an infant or young child to a variety of foods at a young age is effective in promoting liking and intake of both exposed foods and other new foods. Gerrish and Mennella (2001) found that exposure to a variety of foods enhanced acceptance of an unfamiliar food at weaning. In this study, 5-month-old infants consumed more of the target vegetable when they had previously been exposed to either the target vegetable or to a variety of vegetables other than the target food, compared to infants only exposed to potato. Infants in the “variety” condition also consumed more of an unfamiliar meat dish than infants in other conditions. The extent to which exposure to a variety of tastes promotes acceptance of unfamiliar foods may vary according to the specific foods exposed, however. Barends et al. (2013) recently reported that starting complementary feeding with exposure to a variety of vegetables increases acceptance and consumption of fruit and vegetables, while exposing infants to a variety of fruits at the start of weaning does not increase fruit consumption or vegetable acceptance.