Abstract

Background: The extent to which breastfeeding is protective against later-life obesity is controversial. Little is known about differences in infant body composition between breastfed and formula-fed infants, which may reflect future obesity risk.

Objective: We aimed to assess associations of infant feeding with trajectories of growth and body composition from birth to 7 mo in healthy infants.

Design: We studied 276 participants from a previous study of maternal vitamin D supplementation during lactation. Mothers used monthly feeding diaries to report the extent of breastfeeding. We measured infants’ anthropometrics and used dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry to assess body composition at 1, 4, and 7 mo. We compared changes in infant size (z scores for weight, length, and body mass index [BMI (in kg/m2)]) and body composition (fat and lean mass, body fat percentage) between predominantly breastfed and formula-fed infants, adjusting in linear regression for sex, gestational age, race/ethnicity, maternal BMI, study site, and socioeconomic status.

Results: In this study, 214 infants (78%) were predominantly breastfed (median duration: 7 mo) and 62 were exclusively formula fed. Formula-fed infants had lower birth-weight z scores than breastfed infants (−0.22 ± 0.86 and 0.16 ± 0.88, respectively; P < 0.01) but gained more in weight and BMI through 7 mo of age (weight z score difference: 0.37; 95% CI: 0.04, 0.71; BMI z score difference: 0.35; 95% CI: 0, 0.69), with no difference in linear growth (z score difference: 0.05; 95% CI: −0.24, 0.34). Formula-fed infants gained more lean mass (difference: 303 g; 95% CI: 137, 469 g) than breastfed infants, but not fat mass (difference: −42 g; 95% CI: −299, 215 g).

Conclusions: Formula-fed infants gained weight more rapidly and out of proportion to linear growth than did predominantly breastfed infants. These differences were attributable to greater accretion of lean mass, rather than fat mass. Any later obesity risk associated with infant feeding does not appear to be explained by differential adiposity gains in infancy.

Keywords: body composition, infant, growth, breastmilk, breastfeeding, formula, adiposity, obesity

INTRODUCTION

The extent to which breastfeeding in infancy exerts a protective effect against later obesity is still a subject of much debate (1). Formula-fed infants gain more weight out of proportion to length in the first year of life than breastfed infants, resulting in a higher weight-for-length or BMI (in kg/m2) (2–5). This differential growth pattern could contribute to an increased risk of obesity among formula-fed infants, because both higher absolute weight and more rapid weight-for-length gains during infancy are associated with subsequent obesity (6, 7). Furthermore, excess adiposity gain in infancy may be on the causal pathway to greater adiposity later in childhood and into adulthood (8, 9). Understanding the relation between breastfeeding and the accrual of adiposity during infancy may provide insight into the link between breastfeeding and a reduced risk of later-life obesity and its comorbidities.

Noninvasive techniques such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) now enable researchers to distinguish fat from lean mass in infants. Gale et al. (10) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 observational studies and found that formula-fed infants gain more lean mass than breastfed infants through the first year of life, with differences most clearly evident at 3–4 mo (130 g more lean mass in formula-fed infants) and 9–12 mo (300 g more lean mass in formula-fed infants). However, the relation between infant feeding and fat mass accumulation was less consistent, with less fat mass in formula-fed infants at 3–4 and 6 mo of age but more fat mass in formula-fed infants at 8–9 and 12 mo.

Methodologic limitations of previous studies, including those in the meta-analysis by Gale et al. (10), may contribute to the lack of clarity in the relation between breastfeeding and the accumulation of adiposity during infancy. For example, some studies were limited by their cross-sectional design (11, 12) or relatively small sample sizes (20–80 patients) (3, 4, 12–14). Other studies included infants with a short duration or low intensity of breastfeeding in the “breastfed” category (15–17), which could underestimate body composition differences between feeding groups. A few studies (3, 14) assessed adiposity with the use of skinfold thickness, a method that is less accurate and reliable than DXA (18). The protein content of formula has decreased substantially over the last 3 decades (19), which may influence the extent of differences in body composition between breastfed and formula-fed infants and may limit the applicability of findings from older studies. To our knowledge, no large contemporary longitudinal study has yet compared gains in fat and lean mass between formula-fed infants and infants who, in keeping with national and international recommendations (20), are predominantly or exclusively breastfed.

The primary aim of our study was to analyze differences in body composition trajectories between formula-fed and breastfed infants during the first 7 mo of life. Based on the known association of formula feeding with faster infant weight gain (2, 21) and with an increased risk of obesity in childhood (22), we hypothesized that exclusively formula-fed infants would gain more fat mass than would predominantly breastfed infants.

METHODS

Participants

We conducted an observational secondary analysis of data collected during a previously completed randomized trial of maternal vitamin D supplementation (23). Mother-infant dyads were recruited between January 2007 and December 2011 from the newborn nursery at the Medical University of South Carolina and local community obstetricians’ offices in Charleston, South Carolina, as well as from the University of Rochester Strong Memorial Hospital, Rochester General Hospital, and community hospitals in Rochester, New York. Eligibility criteria were as follows: healthy singleton infants born at a gestational age of ≥35 wk, infants aged <6 wk at enrollment, and mothers planning to exclusively breastfeed or exclusively formula feed for 6 mo. Formula-feeding mothers were recruited only from Charleston, whereas breastfeeding mothers were recruited from both sites. Mothers were excluded if they had preexisting hypertension, hypocalcemia, hypercalcemia, parathyroid disease, uncontrolled thyroid disease, or type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus or were taking diuretics or other cardiac medications. Infants were excluded if they had congenital anomalies or an inborn error of metabolism or were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for >72 h.

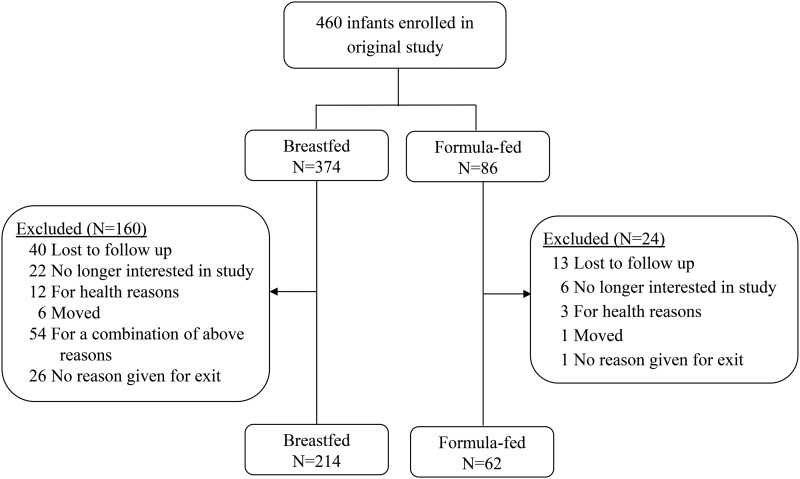

Study visits were conducted monthly, and body composition was measured at 1, 4, and 7 mo of age. For this secondary analysis, we included 276 of 460 infants from the original cohort who had a body composition measurement at 7 mo (virtually all of these patients also had body composition measured at 1 or 4 mo) and had anthropometric and feeding data recorded for ≥2 of the study visits (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study participants.

Measures

Feeding

Mothers were categorized at enrollment as intending to either 1) formula feed exclusively or 2) breastfeed exclusively for 6 mo. None of the mothers intending to formula feed initiated breastfeeding. Breastfeeding mothers used monthly feeding diaries to record the number of times per day in the past 7 d the infant was fed breastmilk, formula, or other liquids or solids and the mode of feeding (direct breastfeeding, bottle, cup, or syringe). We used feeding diaries to calculate breastfeeding intensity, defined as the proportion of total feeds that consisted of breastmilk (as opposed to formula or complementary foods) (24). At each study visit, mothers also completed a questionnaire regarding whether they were still breastfeeding, whether the infant had ever been given formula, the age (in days) at which formula was first given, and the current frequency and volume of formula feeding. We used these questionnaire responses to determine the duration of “exclusive breastfeeding,” defined as the infant’s age in days when formula was first reported to be given (regardless of solid foods). We defined the duration of “any breastfeeding” as the infant’s age in days at the last visit at which the mother reported she was still breastfeeding. If feeding questionnaire data were missing, we used information from the last visit at which feeding information was reported; for example, if feeding data were missing at 6 mo and the mother reported exclusive breastfeeding at 5 mo, we considered the duration of exclusive breastfeeding to be 5 mo.

Anthropometrics

Birth weight was obtained from the infants’ medical records. Trained study staff measured infants’ subsequent weights and lengths monthly starting at 1 mo of age. Infants were weighed on a standard infant scale (Scale-Tronix Inc.) to the nearest gram and length was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm on an infant length board (Perspective Enterprises). Birth-weight z scores were calculated using the 2010 Olsen growth charts (25). All subsequent weight z scores and all length and BMI z scores were calculated from WHO reference data (26) using a 2005 macro (the WHO Child Growth Standards SPSS Syntax File [igrowup.sps]).

Body composition

At 1, 4, and 7 mo of age, infants underwent whole-body DXA scans using a Hologic Discovery A densitometer (Hologic Inc.) with Hologic infant whole-body software (version 12.7.3:3). Both study sites used a Hologic Discovery A densitometer and a spine phantom standard was sent to each site twice during the study period for cross-calibration of the scanners; 20 scans on the phantom standard were performed at each site, with a correlation of 0.998 and no statistically significant differences in body composition of the phantom as measured by the 2 different scanners.

We analyzed the DXA results in 2 ways: we first included bone mineral content in lean mass to represent total body fat-free mass and we then excluded bone mineral content from lean mass. The magnitudes of differences in body composition between breastfed and formula-fed infants were virtually identical with both approaches (data not shown). Here, we report our results with bone mineral content included in lean mass.

Ethics approval

The trial of vitamin D supplementation from which these data were obtained was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Medical University of South Carolina (no. 16536) and the University of Rochester (no. 14460). The use of DXA is safe in infants, with the typical radiation exposure from a DXA scan being equivalent to 1-d exposure to background radiation (18). Informed consent was obtained from parents of infants who participated in the study. This secondary analysis of deidentified data was classified as exempt by the Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Statistical analysis

The primary exposure was infant feeding type, which we chose to analyze as a dichotomous variable defined as “predominantly breastfed” or “never breastfed” (i.e., exclusively formula fed). We took this approach because within the group of breastfed infants, the rate of exclusive breastfeeding to 6 mo was high (70%), with limited variability in breastfeeding duration or intensity. The primary outcomes were measures of infant body composition (fat and lean mass, body fat percentage) assessed at 1, 4, and 7 mo. Secondary outcomes included z scores for weight, length, and BMI at each monthly visit.

We used linear regression to quantify the effects of feeding type on differences in body composition and size at 7 mo of age, adjusting for covariates that we identified a priori as potential confounders based on known associations with feeding type and infant body composition or growth. These covariates included gestational age, sex, race/ethnicity, maternal BMI (measured by research staff at 7 mo postpartum), and insurance type and maternal education as measures of socioeconomic status. We also adjusted for study site. To model the change in body composition or size over time, we also adjusted for the earliest measured value of each outcome. For example, in the regression analysis with the weight z score at 7 mo as the outcome, we adjusted for the birth-weight z score.

To test whether the trajectories of growth in both body composition and size differed between breastfed and formula-fed infants, we used repeated-measures ANOVA with feeding type as the main effect and age in days as the repeated-measures variable, controlling for the same covariates as in the linear regression analyses. To quantify the mean rate of increase or decrease in each group between birth and 7 mo, we fitted a first-degree spline model (segmented regression with random slope perturbations at monthly intervals) using feeding type and time as independent variables and adjusting for the same covariates as above.

Inclusion of the treatment group from the original trial or the vitamin D level at the conclusion of the trial as covariates did not substantially alter the results of any of our analyses and these were not included as covariates in our final model.

We used IBM SPSS Statistics (version 22.0; IBM Corp.) and SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.) software for all analyses.

RESULTS

Characteristics of breastfed and formula-fed infants included in the analysis are shown in Table 1. Infants excluded from the analysis had lower birth weights than infants included in the analysis (mean ± SD: 3268 ± 445 g and 3405 ± 494 g; P = 0.003), were more likely to be African American or Hispanic than white (77% and 49%; P < 0.001), and had less-educated mothers (21% and 43% with a college degree; P < 0.001) who were more likely to have public or no insurance (71% and 49%; P < 0.001). Among included infants in the breastfed group (n = 214), 149 (70%) were exclusively breastfed for 6 mo, and only 28 (13%) completely discontinued breastfeeding before 6 mo. No infant in the formula-fed group received any breastmilk. Most breastfed infants (87%) were occasionally fed expressed milk from a bottle, but the minority of feedings were given this way (mean: 1–2 bottles/d). Formula-fed infants had significantly lower birth-weight z scores (mean: −0.22 vs. 0.16), were more likely to be African American or Hispanic rather than white, and were more likely to be covered by public insurance or no insurance (compared with private insurance) than were breastfed infants. Mothers of formula-fed infants had attained less education and had a higher prepregnancy BMI (mean: 31.2 and 26.7) than mothers of breastfed infants.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of study participants1

| Characteristic | Breastfed infants (n = 214) | Formula-fed infants (n = 62) | P value |

| Male sex | 110 (51) | 34 (55) | 0.67 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| African American | 39 (18) | 23 (37) | |

| Asian | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Caucasian | 122 (57) | 11 (18) | |

| Hispanic | 46 (22) | 28 (45) | |

| Gestational age, wk | 39.4 ± 1.2 | 39.3 ± 1.3 | 0.50 |

| Birth weight, g | 3455 ± 474 | 3249 ± 515 | 0.003 |

| Birth weight, z score | 0.16 ± 0.88 | −0.22 ± 0.86 | 0.003 |

| Maternal BMI,2 kg/m2 | 26.7 ± 6.0 | 31.2 ± 7.8 | <0.001 |

| Maternal weight status,2 BMI | <0.001 | ||

| Underweight, <18 | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Normal weight, 18 to <25 | 103 (48) | 15 (24) | |

| Overweight, 25 to <30 | 50 (23) | 15 (24) | |

| Obese, >30 | 58 (27) | 30 (48) | |

| Maternal gravidity | 2 (1, 9) | 2 (1, 6) | 0.67 |

| Maternal parity | 2 (0, 6) | 2 (1, 6) | 0.18 |

| Mode of delivery | 0.10 | ||

| Vaginal | 163 (76) | 41 (66) | |

| Cesarean section | 49 (23) | 21 (34) | |

| Maternal education level | <0.001 | ||

| High school or less | 50 (24) | 38 (61) | |

| Some college | 37 (17) | 15 (24) | |

| Associate’s degree | 14 (7) | 3 (5) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 47 (22) | 4 (7) | |

| Master’s or doctoral (PhD/ScD/MD) degree | 62 (29) | 2 (3) | |

| Employed during pregnancy | 148 (69) | 36 (58) | 0.13 |

| Maternal insurance | <0.001 | ||

| Private | 122 (57) | 15 (24) | |

| Medicaid | 72 (34) | 38 (61) | |

| Other | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| None | 16 (8) | 9 (15) | |

| Infant admitted to normal newborn nursery (as opposed to special care, level II nursery, or NICU) | 202 (94) | 57 (92) | 0.50 |

| Age at introduction of solids, d | 150 (120, 180) | 120 (100, 120) | <0.001 |

| Ever received pumped breastmilk in a bottle | 187 (87) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Number of bottle feeds/d | |||

| At 1–2 mo | 1 (0, 2) | — | |

| At 3–7 mo | 2 (1, 3) | — | |

| Duration of breastfeeding, d | 212 (191, 217) | — | |

| Duration of exclusive breastfeeding, d | 211 (148, 217) | — | |

| Breastfeeding intensity (percentage of total feeds between 0 and 7 mo that consisted of breastmilk) | 92 (86, 95) | — |

Values are expressed as n (%) for categorical data (compared by using Fisher’s exact test), means ± SDs for normally distributed data (compared by using the t test), or medians (minimums, maximums) for skewed data (maternal BMI, gravidity, parity, and age at introduction of solids; compared by using the Mann-Whitney U test). Feeding data are reported as medians (IQRs). NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Maternal BMI was measured at 7 mo postpartum.

Anthropometric and body composition measures at age 7 mo differed between the breastfed and formula-fed groups (Table 2). Specifically, at age 7 mo, formula-fed infants had weight z scores that were 0.37 U (95% CI: 0.04, 0.71 U) and BMI z scores that were 0.35 U (95% CI: 0, 0.69 U) higher than breastfed infants, although length z scores were similar between the 2 groups (difference: 0.05; 95% CI: −0.24, 0.34). The extra weight in formula-fed infants was almost entirely attributable to having 303 g more lean mass, whereas fat mass and body fat percentages were not different between feeding groups (P = 0.75 and P = 0.15, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Associations of infant feeding with anthropometrics and body composition at 7 mo of age

| Outcome at 7 mo | Breastfed infants1 | Formula-fed infants1 | Adjusted difference between formula-fed and breastfed infants2 | P value3 |

| z Score | ||||

| Weight | −0.13 ± 0.07 | 0.19 ± 0.14 | 0.37 (0.04, 0.71) | 0.03 |

| BMI | 0.05 ± 0.08 | 0.63 ± 0.14 | 0.35 (0, 0.69) | 0.05 |

| Length | −0.28 ± 0.07 | −0.47 ± 0.12 | 0.05 (−0.24, 0.34) | 0.73 |

| Mass, g | ||||

| Lean | 5242 ± 51 | 5912 ± 81 | 303 (137, 469) | <0.001 |

| Fat | 2950 ± 59 | 2942 ± 113 | −42 (−299, 215) | 0.75 |

| Total | 8192 ± 74 | 8854 ± 144 | 355 (34, 675) | 0.03 |

| Body fat, % | 35.6 ± 0.5 | 32.7 ± 0.9 | −1.6 (−3.8, 0.6) | 0.15 |

Values are expressed as unadjusted means ± SEs for each feeding group.

Values are expressed as difference in formula-fed infants compared with breastfed infants, after adjustments in linear regression for sex, gestational age, initial body size and composition, race/ethnicity, maternal education level, insurance type, study site, and maternal BMI. Positive numbers indicate a larger size or higher mass in formula-fed infants.

P values are for the adjusted difference between formula-fed and breastfed infants.

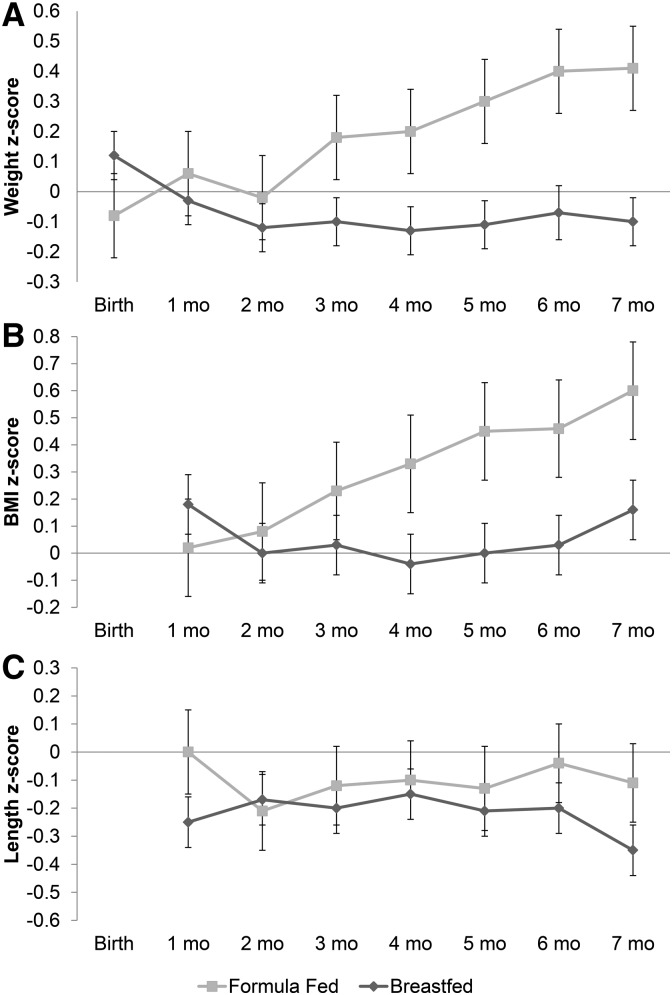

Trajectories of weight, length, and BMI z scores in breastfed and formula-fed infants are shown in Figure 2. After we adjusted for covariates, weight and BMI z score trajectories differed between breastfed and formula-fed infants (P < 0.001 and P = 0.02, respectively). Specifically, weight z scores of breastfed infants decreased slightly over 7 mo (−0.03 U/mo; P = 0.004), whereas weight z scores of formula-fed infants increased by 0.07 U/mo (P = 0.001). BMI z scores also increased by 0.08 U/mo (P < 0.001) in formula-fed infants, whereas BMI z scores of breastfed infants remained constant (−0.005 U/mo; P = 0.71). Length z score trajectories were not statistically different between the 2 groups (P = 0.16).

FIGURE 2.

Trajectories of z scores for infant weight (A), BMI (B), and length (C) in formula-fed and breastfed infants. Results are displayed as estimated mean z scores ± SEMs from repeated-measures ANOVA adjusted for sex, gestational age, race/ethnicity, maternal education level, insurance type (public or no insurance, private insurance), study site, and maternal BMI. Weight and BMI z scores of formula-fed infants increased progressively over time, whereas they remained consistent in breastfed infants. These trajectories in weight and BMI z scores were statistically different between feeding groups (P < 0.001 and P = 0.02, respectively) whereas length z score trajectories were not (P = 0.16).

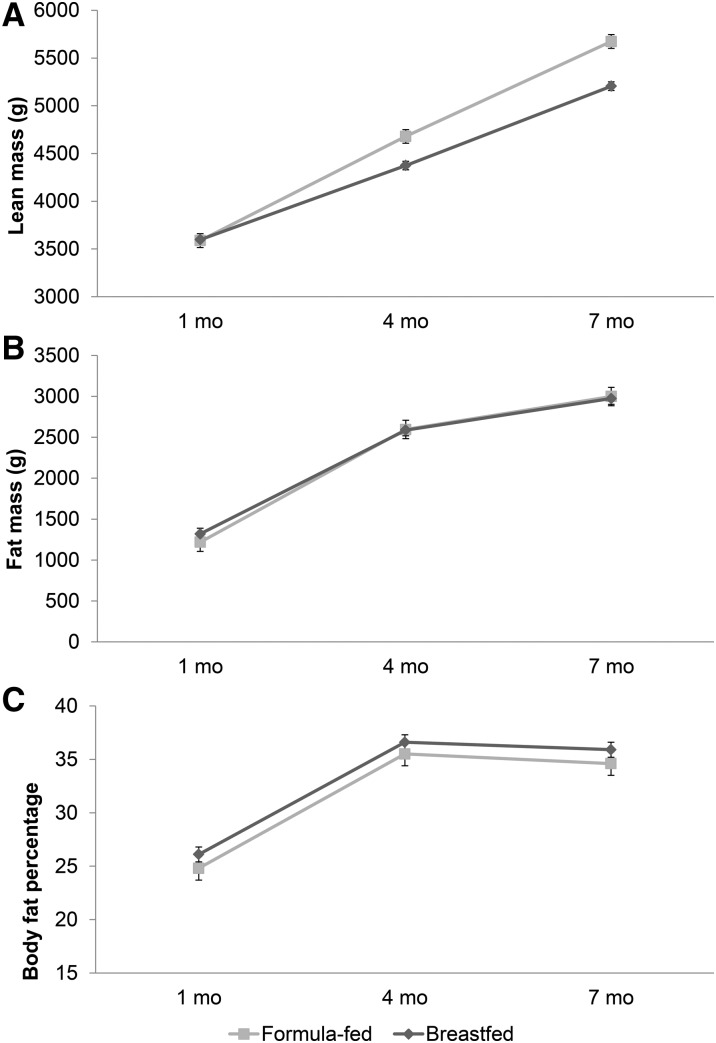

Trajectories of body composition including fat mass, lean mass, and body fat percentage are shown in Figure 3, after adjustment for covariates. Both breastfed and formula-fed infants gained fat mass at a similar rate (P = 0.57), and body fat percentages also remained similar between the 2 groups (P = 0.61). Formula-fed infants gained more lean mass than did breastfed infants (11.5 g/d and 9.2 g/d, respectively; P < 0.001).

FIGURE 3.

Trajectories of infant lean mass (A), fat mass (B), and body fat percentage (C) in formula-fed and breastfed infants. Results are displayed as estimated means ± SEMs from repeated-measures ANOVA adjusted for sex, gestational age, race/ethnicity, maternal education level, insurance type (public or no insurance, private insurance), study site, and maternal BMI. Formula-fed infants gained significantly more lean mass than did breastfed infants (P < 0.001), although fat mass and body fat percentages were similar between groups (P = 0.57 and P = 0.61, respectively).

DISCUSSION

We used data from a large, longitudinal birth cohort to compare trajectories of growth and body composition among predominantly breastfed and exclusively formula-fed infants during the first 7 mo of infancy. Consistent with most (2, 5, 27), but not all (28), prior research studies, we found that formula-fed infants gained weight more rapidly than breastfed infants and they gained weight out of proportion to their linear growth, translating to progressively increasing BMI z scores over time. Our study extends prior research by demonstrating that this excess weight gain did not represent an excess gain in adiposity but instead reflected progressively greater gains in lean mass throughout the first 7 mo of life. This lack of excess adiposity gain in formula-fed infants argues against the frequently cited hypothesis that excess adipose tissue accumulated during infancy underlies the association of infant formula feeding with later-life obesity (9, 22, 27, 29).

Fat mass

We found no difference in fat mass at 1, 4, or 7 mo between formula-fed and breastfed infants, nor did we find any difference in the overall trajectory of adiposity (fat mass or body fat percentage) gain between groups over this time period. Several contemporary studies (30–32) also showed no difference in fat mass between predominantly or exclusively breastfed and formula-fed infants from 2 to 4 mo of age. In contrast with our findings, a few prior studies reported either lower (17) or higher (33) fat mass in formula-fed infants and a meta-analysis (10) showed that fat mass is lower in formula-fed infants at 3–4 and 6 mo of life. However, prior studies, including those in the meta-analysis by Gale et al. (10), were limited in several ways, including small sample sizes (20–80 patients) (3, 4, 13, 14, 33), inclusion of partially breastfed infants in the formula-fed group (17), and the use of formulas with a substantially different nutrient composition than those in current practice, with ≤2 times the usual protein content (33). Furthermore, meta-analyses may overestimate the difference between groups if publication bias exists for small studies that find a difference owing to chance; the difference in fat mass in the meta-analysis appears to be driven by large effect sizes found in a few very small studies (12, 34). Overall, there appears to be very little, if any, association of infant feeding mode with gains in adiposity during early infancy.

These findings are relevant in the context of the link between formula feeding and later obesity risk (22, 27, 29). The accumulation of excess adipose tissue during infancy is hypothesized to play an important role in the early-life programming of obesity (9), and the association between formula feeding and increased weight-for-length gain in infancy has been interpreted as representing increased adiposity (2, 35, 36). In contrast, our findings show that the early excess weight gain out of proportion to linear growth that is associated with formula feeding represents lean mass rather than adipose tissue. Thus, the link between early formula feeding and later obesity (37) is likely to be explained by pathways other than excess adipose tissue gain. Additional factors that may contribute to increased obesity risk in formula-fed infants include differences in patterns of solid food intake (38), effects of bottle-feeding on self-regulation of feeding (39), absence of exposure to bioactive substances found in breastmilk that may inhibit adipogenesis (29), or alterations in the distribution (rather than quantity) of fat deposition in infancy (31, 40). Alternatively, lean mass gain in infancy, rather than adipose tissue gain, may be on the causal pathway to later-life obesity.

Lean mass

Our finding of greater lean mass in formula-fed infants is consistent with the few contemporary studies that used accurate, noninvasive techniques to measure infant body composition. In one study that used DXA, predominantly formula-fed infants had 310 g more lean mass at 6 mo than exclusively breastfed infants (17). Similarly, Giannì et al. (30) used air-displacement plethysmography and found that exclusively formula-fed infants had ∼200 g more lean mass than exclusively breastfed infants at 4 mo of age. These differences are reasonably consistent in magnitude with the 303-g difference in lean mass that we found at 7 mo. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that compared with predominantly breastfed infants, formula-fed infants have substantially greater lean mass that is detectable as early as 3 mo of age.

Greater lean mass gain in formula-fed compared with breastfed infants is biologically plausible. Despite attempts to mimic the macronutrient content of breastmilk in formula, the protein concentration of standard infant formula in the United States remains higher than the typical protein concentration of breastmilk (41). Formula-fed infants ingest more protein in the first 6 mo of life (4), and greater protein intake is associated with greater lean body mass accretion in infancy (42). In a large randomized controlled trial of higher- and lower-protein formula, infants fed the higher-protein formula gained weight more rapidly during infancy and had a higher obesity risk at 6 y (33, 43). The same trial showed no significant differences in body composition at 6 mo between the high- and low-protein groups, but the investigators only assessed a small subsample of <25 infants/group (33). The increased obesity risk in infants fed the higher-protein formula suggests that protein intake in infancy could be on the causal pathway leading to subsequent obesity. Taken together, our study and others suggest that the mechanism by which lower protein intake during infancy (either through breastfeeding or lower-protein formula) is protective against later obesity may involve differences in early lean mass accumulation.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include its longitudinal design and a large, racially diverse cohort. To our knowledge, this is the largest and most diverse study of infant feeding and body composition published to date. We determined body composition 3 times in early infancy using DXA, which is precise and accurate in infants, particularly for repeated measurements on the same scanner (44). However, because of the small body size of young infants, DXA scans cannot assess the distribution of body fat, which may differ between formula-fed and breastfed infants (31, 40). We measured and adjusted for several variables that could confound the relation of infant feeding with growth and body composition, including birth weight (45), maternal BMI (from 7 mo postpartum because prepregnancy BMI was not available) (3, 40), and socioeconomic status as represented by maternal education and insurance status (46). However, as in all observational studies, the possibility of residual confounding remains. Breastfeeding was of a high intensity and long duration in our cohort, which allowed us to make inferences about differences between infants breastfed as currently recommended (exclusively for 6 mo) and exclusively formula-fed infants. However, we were not able to determine the extent to which differences in the degree of breastfeeding (e.g., shorter duration or mixed formula and breastfeeding) contribute to differences in infant body composition, which may limit the generalizability of our findings, especially because relatively few infants breastfeed in accordance with recommendations (47). We were not able to measure the exact nutrient composition of the formulas used by mothers in this study, but the composition of infant formula is tightly regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (48); therefore, we expect a high degree of consistency across brands. An additional limitation is that we lacked data on infant growth and body composition beyond 7 mo, so we were not able to assess for persistent differences in body composition beyond the weaning period.

We found that exclusively formula-fed infants gained lean mass (but not fat mass) more rapidly than predominantly breastfed infants over the first 7 mo of life. Although the long-term health consequences of differences in infant body composition are unknown, our findings suggest that differences in fat accumulation during infancy are unlikely to explain the previously observed association between infant feeding and future obesity risk.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cynthia R Howard and Ruth A Lawrence (University of Rochester) and Bruce W Hollis (Medical University of South Carolina Children’s Hospital) for contributions to the original trial from which this secondary analysis was performed. The authors also thank Myla Ebeling and Judith Shary (Medical University of South Carolina) for assistance with database management.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—CLW: designed the original research study for which the data used in this analysis were collected; KAB, CLW, HAF, and MBB: designed the analysis; KAB and HAF: analyzed the data; KAB: wrote the paper and had primary responsibility for the final content; and all authors: contributed to the interpretation of the findings and read and approved the final manuscript. None of the authors reported a conflict of interest related to the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gillman MW. Commentary: breastfeeding and obesity–the 2011 Scorecard. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:681–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dewey KG. Growth characteristics of breast-fed compared to formula-fed infants. Biol Neonate 1998;74:94–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewey KG, Heinig MJ, Nommsen LA, Peerson JM, Lönnerdal B. Breast-fed infants are leaner than formula-fed infants at 1 y of age: the DARLING study. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;57:140–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butte NF, Wong WW, Hopkinson JM, Smith EO, Ellis KJ. Infant feeding mode affects early growth and body composition. Pediatrics 2000;106:1355–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rebhan B, Kohlhuber M, Schwegler U, Fromme H, Abou-Dakn M, Koletzko BV. Breastfeeding duration and exclusivity associated with infants’ health and growth: data from a prospective cohort study in Bavaria, Germany. Acta Paediatr 2009;98:974–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Belfort MB, Kleinman KP, Oken E, Gillman MW. Weight status in the first 6 months of life and obesity at 3 years of age. Pediatrics 2009;123:1177–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monteiro PO, Victora CG. Rapid growth in infancy and childhood and obesity in later life–a systematic review. Obes Rev 2005;6:143–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pirilä S, Saarinen-Pihkala UM, Viljakainen H, Turanlahti M, Kajosaari M, Mäkitie O, Taskinen M. Breastfeeding and determinants of adult body composition: a prospective study from birth to young adulthood. Horm Res Paediatr 2012;77:281–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koontz MB, Gunzler DD, Presley L, Catalano PM. Longitudinal changes in infant body composition: association with childhood obesity. Pediatr Obes 2014;9:e141–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gale C, Logan K, Santhakumaran S, Parkinson J, Hyde M, Modi N. Effect of breastfeeding compared with formula feeding on infant body composition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:656–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chomtho S, Wells JC, Davies PS, Lucas A, Fewtrell MS. Early growth and body composition in infancy. Adv Exp Med Biol 2009;646:165–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang Z, Yan Q, Su Y, Acheson KJ, Thélin A, Piguet-Welsch C, Ritz P, Ho ZC. Energy expenditure of Chinese infants in Guangdong Province, south China, determined with use of the doubly labeled water method. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:1256–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motil KJ, Sheng HP, Montandon CM, Wong WW. Human milk protein does not limit growth of breast-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1997;24:10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Bruin NC, Degenhart HJ, Gàl S, Westerterp KR, Stijnen T, Visser HK. Energy utilization and growth in breast-fed and formula-fed infants measured prospectively during the first year of life. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:885–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellù R, Ortisi MT, Agostoni C, Riva E, Giovannini M. Total body electrical conductivity derived measurement of the body composition of breast or formula-fed infants at 12 months. Nutr Res 1997;17:23–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson AK. Association between infant feeding and early postpartum infant body composition: a pilot prospective study. Int J Pediatr 2009;2009:648091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andres A, Casey P, Cleves M, Badger T. Body fat and bone mineral content of infants fed breast milk, cow’s milk formula, or soy formula during the first year of life. J Pediatr 2013;163:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demerath EW, Fields DA. Body composition assessment in the infant. Am J Hum Biol 2014;26:291–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koletzko B, von Kries R, Closa R, Escribano J, Scaglioni S, Giovannini M, Beyer J, Demmelmair H, Gruszfeld D, Dobrzanska A, et al. Lower protein in infant formula is associated with lower weight up to age 2 y: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1836–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston M, Landers S, Noble L, Szucs K, Viehmann L; Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics 2012;129:e827–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agostoni C, Grandi F, Giannì ML, Silano M, Torcoletti M, Giovannini M, Riva E. Growth patterns of breast fed and formula fed infants in the first 12 months of life: an Italian study. Arch Dis Child 1999;81:395–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patro-Gołąb B, Zalewski BM, Kołodziej M, Kouwenhoven S, Poston L, Godfrey KM, Koletzko B, van Goudoever JB, Szajewska H. Nutritional interventions or exposures in infants and children aged up to 3 years and their effects on subsequent risk of overweight, obesity and body fat: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Obes Rev 2016;17:1245–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollis BW, Wagner CL, Howard CR, Ebeling M, Shary JR, Smith PG, Taylor SN, Morella K, Lawrence RA, Hulsey TC. Maternal versus infant vitamin D supplementation during lactation: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2015;136:625–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piper S, Parks PL. Use of an intensity ratio to describe breastfeeding exclusivity in a national sample. J Hum Lact 2001;17:227–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olsen IE, Groveman SA, Lawson ML, Clark RH, Zemel BS. New intrauterine growth curves based on United States data. Pediatrics 2010;125:e214–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr Suppl 2006;450:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oddy WH, Mori TA, Huang R-CC, Marsh JA, Pennell CE, Chivers PT, Hands BP, Jacoby P, Rzehak P, Koletzko BV, et al. Early infant feeding and adiposity risk: from infancy to adulthood. Ann Nutr Metab 2014;64:262–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kramer MS, Guo T, Platt RW, Sevkovskaya Z, Dzikovich I, Collet J-PP, Shapiro S, Chalmers B, Hodnett E, Vanilovich I, et al. Infant growth and health outcomes associated with 3 compared with 6 mo of exclusive breastfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78:291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arenz S, Rückerl R, Koletzko B, von Kries R. Breast-feeding and childhood obesity–a systematic review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004;28:1247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giannì ML, Roggero P, Morlacchi L, Garavaglia E, Piemontese P, Mosca F. Formula‐fed infants have significantly higher fat‐free mass content in their bodies than breastfed babies. Acta Paediatr 2014;103:e277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gale C, Thomas EL, Jeffries S, Durighel G, Logan KM, Parkinson JR, Uthaya S, Santhakumaran S, Bell JD, Modi N. Adiposity and hepatic lipid in healthy full-term, breastfed, and formula-fed human infants: a prospective short-term longitudinal cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99:1034–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carberry AE, Colditz PB, Lingwood BE. Body composition from birth to 4.5 months in infants born to non-obese women. Pediatr Res 2010;68:84–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Escribano J, Luque V, Ferre N, Mendez-Riera G, Koletzko B, Grote V, Demmelmair H, Bluck L, Wright A, Closa-Monasterolo R; European Childhood Obesity Trial Study Group. Effect of protein intake and weight gain velocity on body fat mass at 6 months of age: the EU childhood obesity programme. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012;36:548–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butte NF, Wong WW, Fiorotto M, Smith EO, Garza C. Influence of early feeding mode on body composition of infants. Biol Neonate 1995;67:414–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dewey KG, Heinig MJ, Nommsen LA, Peerson JM, Lönnerdal B. Growth of breast-fed and formula-fed infants from 0 to 18 months: the DARLING study. Pediatrics 1992;89:1035–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belfort MB, Gillman MW, Buka SL, Casey PH, McCormick MC. Preterm infant linear growth and adiposity gain: trade-offs for later weight status and intelligence quotient. J Pediatr 2013;163:1564–9.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boeke CE, Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Gillman MW. Correlations among adiposity measures in school-aged children. BMC Pediatr 2013;13:99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wen X, Kong KL, Eiden RD, Sharma NN, Xie C. Sociodemographic differences and infant dietary patterns. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1387–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartok CJ, Ventura AK. Mechanisms underlying the association between breastfeeding and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes 2009;4:196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ay L, Van Houten VAA, Steegers EA, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Jaddoe VW, Hokken-Koelega AC. Fetal and postnatal growth and body composition at 6 months of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:2023–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abrams SA, Hawthorne KM, Pammi M. A systematic review of controlled trials of lower-protein or energy-containing infant formulas for use by healthy full-term infants. Adv Nutr 2015;6:178–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heinig MJ, Nommsen LA, Peerson JM, Lonnerdal B, Dewey KG. Energy and protein intakes of breast-fed and formula-fed infants during the first year of life and their association with growth velocity: the DARLING study. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;58:152–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weber M, Grote V, Closa-Monasterolo R, Escribano J, Langhendries J-PP, Dain E, Giovannini M, Verduci E, Gruszfeld D, Socha P, et al. Lower protein content in infant formula reduces BMI and obesity risk at school age: follow-up of a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99:1041–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rigo J. Body composition during the first year of life. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program 2006;58:65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Beer M, Vrijkotte TG, Fall CH, van Eijsden M, Osmond C, Gemke RJ. Associations of infant feeding and timing of linear growth and relative weight gain during early life with childhood body composition. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39:586–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haschke HV. The influence of nutritional and genetic factors on growth and BMI until 5 years of age. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2003;151:S54–7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.CDC. Breastfeeding among U.S. children born 2002–2013, CDC National Immunization Surveys [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Dec 12]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/NIS_data.

- 48.Food and Drug Administration Infant Formula Regulations. US Government Electronic Code of Federal Regulations: Title 21, Chapter I, Subchapter B, Part 107 [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 May 2]. Available from: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=cab9b09f0b06886c6d315a87a88a732f&mc=true&node=pt21.2.107&rgn=div5#sp21.2.107.d.