Abstract

This paper first introduces important conceptual and practical distinctions among three key terms: substance “use,” “misuse,” and “disorders” (including addiction), and goes on to describe and quantify the important health and social problems associated with these terms. National survey data are presented to summarize the prevalence and varied costs associated with misuse of alcohol, illegal drugs, and prescribed medications in the United States.

With this as background, the paper then describes historical views, perspectives, and efforts to deal with substance misuse problems in the United States and discusses how basic, clinical, and health service research, combined with recent changes in healthcare legislation and financing, have set the stage for a more effective, comprehensive public health approach.

SUBSTANCE USE AND HEALTH IN AMERICA

As a country, we have a serious substance misuse problem — use of alcohol, illegal drugs, and/or prescribed medications in ways that produce harms to ourselves and those around us. These harms are significant financially with total costs of more than $420 billion annually and more than $120 billion in healthcare (1,2). But these problems are not simply financial burdens — they deteriorate the quality of our health, educational, and social systems, and they are debilitating and killing us — particularly our young through alcohol-related car crashes, drug related violence, and medication overdoses.

Most Americans are already painfully aware of the size and cost of substance misuse problems. Many Americans believe that there are no viable solutions to what they think of as these unfortunate “lifestyle problems” — that they are as intractable as poverty and ignorance. However, a review of the available science offers a much more optimistic projection for our efforts to reduce these problems. As will be discussed, substance misuse can reasonably be considered a lifestyle problem, but there are effective prevention policies and practices that could significantly reduce the harms and costs of these problems. Genetic, brain imaging, and neurobiological science suggests that “addiction” is qualitatively different from substance use and is now best understood as an acquired chronic illness, similar in many respects to type 2 diabetes — illnesses that can be managed but not yet cured.

In this regard, science has already produced a range of effective interventions, treatment medications, behavioral therapies, and recovery support services that make full recovery from even serious addictions an expectable result of professional, continuing, evidenced-based care. Also, recent changes in healthcare insurance regulation and financing now open the door to integration of prevention and treatment of substance use disorders into mainstream medicine in ways that were previously not possible.

Thus, the first and perhaps most important message from this paper is NOT that that substance misuse and disorders cause immensely expensive and socially devastating harms and costs. Rather, the major message from this paper is that science now offers a public health-oriented approach to translate the available science into effective, practical, and sustainable policies and practices to prevent substance “use” before it starts; identify and intervene early with emerging cases of substance “misuse”; and effectively treat serious substance use disorders.

WHAT IS A “SUBSTANCE?”

In this paper a “substance” is defined as any psychoactive compound with the potential to cause health and social problems, including addiction. These substances may be legal (e.g., alcohol and tobacco); illegal (e.g., heroin and cocaine); or controlled for use by licensed prescribers for medical purposes such as hydrocodone or oxycodone (e.g., Oxycontin, Vicodin, and Lortab). These substances can be arrayed into seven classes based on their pharmacological and behavioral effects:

Nicotine — cigarettes, vapor-cigarettes, cigars, chewing tobacco, and snuff

Alcohol — including all forms of beer, wine, and distilled liquors

Cannabinoids — Marijuana, hashish, hash oil, and edible cannabinoids

Opioids — Heroin, methadone, buprenorphine, Oxycodone, Vicodin, and Lortab

Depressants — Benzodiazepines (e.g., Valium, Librium, and Xanax) and Barbiturates (e.g., Seconal)

Stimulants — Cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, methylphenidate (e.g., Ritalin), and atomoxetine (e.g., Stratera)

Hallucinogens — LSD, mescaline, and MDMA (e.g., Ecstasy)

SUBSTANCE MISUSE PROBLEMS AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Although different in many respects, all substances discussed here share three features that make them important to public health and safety. First, all are widely used and misused: 61 million people in the United States admitted to binge drinking in the past year and more than 44 million people used an illicit or non-prescribed drug in the past year (3). Second, using any of these substances at high doses or in inappropriate situations can cause a health or social problem — immediately or over time. This is called substance misuse. One important and very prevalent type of substance misuse is binge drinking. Binge drinking for men is drinking 5 or more standard alcoholic drinks in one sitting (a few hours). For women, it is drinking 4 or more standard alcoholic drinks in one sitting (4). The health and social problems from misuse of alcohol or any of the other above substances can be as simple as low severity and transient embarrassment. But misuse can also result in serious, enduring, and costly consequences, such as an arrest for driving under the influence (DUI), an automobile crash, intimate partner and sexual violence, child abuse and neglect, suicide attempts and fatalities, a stroke, or an overdose death.

The third feature shared by all of the above substances is that prolonged, repeated use of any of these substances at high doses and/or high frequencies (quantity/frequency thresholds vary across substances) can produce not only the kinds of problems described above, but a separate, independent, diagnosable illness that significantly impairs health and function and may require special treatment. This illness is called a substance use disorder. Disorders can range from mild and temporary to severe and chronic. Severe and chronic substance use disorders are commonly called addictions (diagnosis discussed below).

PREVALENCE OF SUBSTANCE MISUSE PROBLEMS AND DISORDERS

To understand the scope, severity, and societal costs of substance use in the United States, it is first necessary to understand just how many people use these substances and at what level of severity. Table 1 provides selected findings from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) (4) on a sample of 265 million individuals 12 years of age and older.

TABLE 1.

2015 Prevalence of Use, New Initiation, and Severe Disorders by Substance

| Type of Drug | Used in Past Year, n (%) | Initiated in Past Year, n (%) | Substance Use Disordera in Past Year, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy alcohol drinkingb | 16.3 (23.0) | 4.7 (1.8) | 17.0 (6.4) |

| Marijuana | 35.0 (13.2) | 2.6 (1.0) | 4.2 (1.6) |

| Opioids (heroin and prescription drugs) | 11.2 (4.2) | 1.6 (0.6) | 2.5 (1.1) |

| Sedatives/tranquilizers | 6.0 (2.3) | 1.3 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.3) |

| Stimulants including methamphetamine | 3.7 (1.4) | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.2) |

| Hallucinogens | 4.3 (1.6) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.1) |

| Cocaine | 4.6 (1.7) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.3) |

| Any of the above except alcohol | 44.0 (17.0) | 7.8 (2.9) | 21.4 (8.1) |

Numbers are in millions and represent 265 million individuals 12 years of age and older.

Met DSM-IV criteria for Abuse or Dependence (approximates DSM-5 diagnosis of “Substance Use Disorder”).

Drinking 5 or more drinks for males and 4 or more drinks for females in one occasion (2 to 3 hours) 5 or more times in the past year.

As shown in Table 1, approximately 17% of the 12 years of age or older population (44 million people) reported use of an illegal drug, non-medical use of a prescribed drug, or heavy alcohol use during the prior year. Almost 3% (7.8 million) initiated some form of substance use in the prior year; and 8% (21.4 million) met diagnostic criteria for a substance use disorder.

Several specific findings shown in Table 1 bear emphasis. For example, more than 34 million people reported “heavy drinking” in the past year [binge drinking 5 or more times (4)]. As indicated, this level of alcohol use is associated with many health and social problems. Marijuana was the most frequently used drug (35 million past year users) and use has increased significantly over the past 5 years, likely as a result of the many state laws that have approved its use for medical purposes or even non-medical use. Medical marijuana is now legal in 28 states, and 8 states have voted to legalize recreational marijuana.

Non-medical use of prescription drugs was reported by almost 15 million individuals in the national survey (5.5% of the population). Within this category, prescribed brand-name opioid pain relievers (e.g., Oxycontin, Vicodin, and Lortab,) accounted for 69% of the prevalence (10 million people) followed by sedatives/tranquilizers (e.g., Valium and Xanax) or stimulants (e.g., Adderall or Ritalin), each reported by 4 million people.

Significance of Substance Misuse

It may be thought that a discussion of substance use and misuse is secondary to the real issue of addiction that has captured so many media headlines and has been linked to so many social problems. This is an important misconception: the great majority of substance-related health and social problems occur among those who are not addicted. Individuals with severe substance use disorders (addictions) do have high rates of substance misuse-related health and social problems and costs; but as shown in Table 1, these individuals are a rather small proportion of the misusing population.

Perhaps the best example of this is binge drinking, which was self-reported by 61 million individuals in 2015. By definition, each misuse episode carries the potential for immediate harm to the user and/or to those around them (e.g., car accident, violence, or alcohol poisoning). However, only 17 million individuals — approximately 28% of all binge drinkers — met diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder. Similarly, approximately 2.5 million people met diagnostic criteria for an opioid use disorder, but more than 11 million individuals misused heroin or a prescribed opioid medication in the past year — setting the occasion for a potential overdose.

One particularly clear implication from these findings is that reducing the harms and costs of substance related problems in the United States cannot occur simply by treating addictions. The greatest public health benefit will come from reducing substance misuse in the general population. Of course, reducing population rates of substance misuse will also reduce rates of addiction (see below).

Harms and Costs Associated With Substance Misuse

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate binge drinking costs the United States approximately $249 billion each year (5) in lost workplace productivity, health care expenses for medical problems associated with binge drinking, law enforcement costs, and costs of motor vehicle crashes. Similarly, the National Drug Intelligence Center found that misuse of illegal drugs and non-prescribed medications cost the United States more than $193 billion per year (2). Again, these costs were due primarily to lost productivity by working substance misusers (62%) and criminal justice costs for drug-related crimes (32%).

Medical costs associated with undiagnosed, untreated substance misuse and substance use disorders have been estimated at more than $120 billion annually. The general population prevalence of substance use disorders is 8% to 10% (6% to 7% for women, 9% to 11% for men), but the prevalence is far higher in all areas of medical care — from approximately 20% in typical primary care clinics, to 40% in general medical patients treated in hospital, to more than 70% of patients in emergency or urgent care clinics. A recent study showed that the presence of an early substance use disorder often doubles the odds for the subsequent development of chronic and expensive medical illnesses such as arthritis, chronic pain, heart disease, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, and asthma (6). In general medical practice, failure to detect and address substance use has been associated with misdiagnoses (7), poor adherence to prescribed care (8), high use of hospital and emergency services (9), and even deaths.

Despite the extraordinary costs, morbidity, and mortality associated with substance misuse it has been broadly overlooked throughout all of healthcare. This has been a costly mistake, with often deadly consequences.

OVERDOSE INCIDENTS AND DEATHS

Poisoning, or overdose, deaths are typically caused by binge drinking at high intensity and/or by consuming combinations of substances such as alcohol, sedatives, tranquilizers, and opioid pain relievers to the point where there is inhibition of critical brain areas that control breathing, heart rate, and body temperature.

Alcohol Overdose

The CDC reported more than 2,200 alcohol poisoning deaths in 2014 — an average of six deaths every day (10). Importantly, approximately 70% of those alcohol-overdose deaths occurred among those who did not meet diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence; nor were they using other drugs at the time of the death (10).

Opioid Overdose (Heroin and Prescribed Opioids)

Opioid analgesic pain relievers are now the most prescribed class of medications in the United States with more than 289 million prescriptions written each year (11,12). The increase in prescriptions of these powerful analgesics has been accompanied by a 300% increase since 2000 in both rates of overdose incidents (478,000) and overdose deaths (18,893 involving prescription opioids and 10,500 involving heroin) in 2014 (13,14).

To address this problem, researchers, medical societies, and the CDC have suggested “…(1) screening patients for use…of alcohol and/or street drugs; (2) taking extra precautions when prescribing medicines with known dangerous interactions with alcohol and/or street drugs; and (3) teaching the patient the risks of mixing medicines with alcohol and/or street drugs” (15). Again, screening for substance use and substance use disorders before and during the course of opioid prescribing, combined with patient education, are recommended (15).

Again, despite these and other indications of extreme threats to healthcare quality, safety, effectiveness, and cost containment, as of this writing, few general healthcare organizations screen for, or offer services for, the early identification and treatment of substance use disorders. Moreover, few medical, nursing, dental, or pharmacy schools teach their students about substance use disorders.

WHO IS MOST VULNERABLE TO SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

As is the case with most other chronic illnesses, 40% to 70% of a person’s risk for developing a substance use disorder is genetic (16), but many environmental factors interact with a person’s genes to modify their risk, such as being raised in a home in which the parents or other relatives use alcohol or drugs (17,18) or living in neighborhoods and going to schools with high prevalence of alcohol and drug misuse are also risk factors (17,19, 20).

Risk and Protective Factors: Keys to Vulnerability

Neither substance misuse problems nor substance use disorders are inevitable. An individual’s vulnerability can be predicted by assessing the nature and number of their personal and environmental risk and protective factors.

Significant environmental risk factors for both substance misuse and disorders include easy access to inexpensive alcohol and other substances, heavy advertising of these products, particularly to youth, low parental monitoring, and high levels of family conflict (16). Environmental protective factors include availability of healthy recreational and social activities, and regular supportive monitoring by parents (16).

At the personal level, major risk factors include a family history of substance use or mental disorders, a current mental health problem, low involvement in school, a history of abuse and neglect, and family conflict and violence (16). Some important personal protective factors include involvement in school, involvement in healthy recreational/social activities, and development of good coping skills (16).

Prevention science has concluded that there are three important points regarding vulnerability. First, no single personal or environmental factor determines whether an individual will have a substance misuse problem or disorder. Second, most risk and protective factors can be modified through preventive policies and programs to reduce vulnerability. Finally, although substance misuse problems and disorders may occur at any age, adolescence and young adulthood are particularly critical at-risk periods.

With regard to substance use disorders, research now indicates that more than 85% of those who meet criteria for a substance use disorder sometime in their lifetime do so during adolescence (21). Put differently, young adults who transition the adolescent years without meeting criteria for a substance use disorder are not likely to ever develop one (21, 22).

Neurobiological research has identified one likely reason for elevated adolescent vulnerability. Alcohol and other substances have particularly potent effects on undeveloped brain circuits and recent scientific findings indicate that brain development is not complete until approximately 21 to 23 years of age in women and 23 to 25 years of age in men (23–25). Among the last brain region to reach maturity is the prefrontal cortex, the brain region primarily responsible for “adult” abilities such as delay of reward, extended reasoning, and inhibition. These findings combine to suggest that adolescence is perhaps the most critical period for prevention and early interventions.

HOW ARE SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS DIAGNOSED?

Changes in Medical Understanding About the Etiology of Substance Use Disorders

Until the recently, the continued use of substances “despite adverse consequences” was considered substance abuse. In contrast, addiction was the diagnostic term reserved for conditions manifest by physiological tolerance and withdrawal. This suggested that only substances capable of producing tolerance and withdrawal (so-called “hard drugs”) could be addictive and that substances such as marijuana, LSD, and even cocaine were relatively safer.

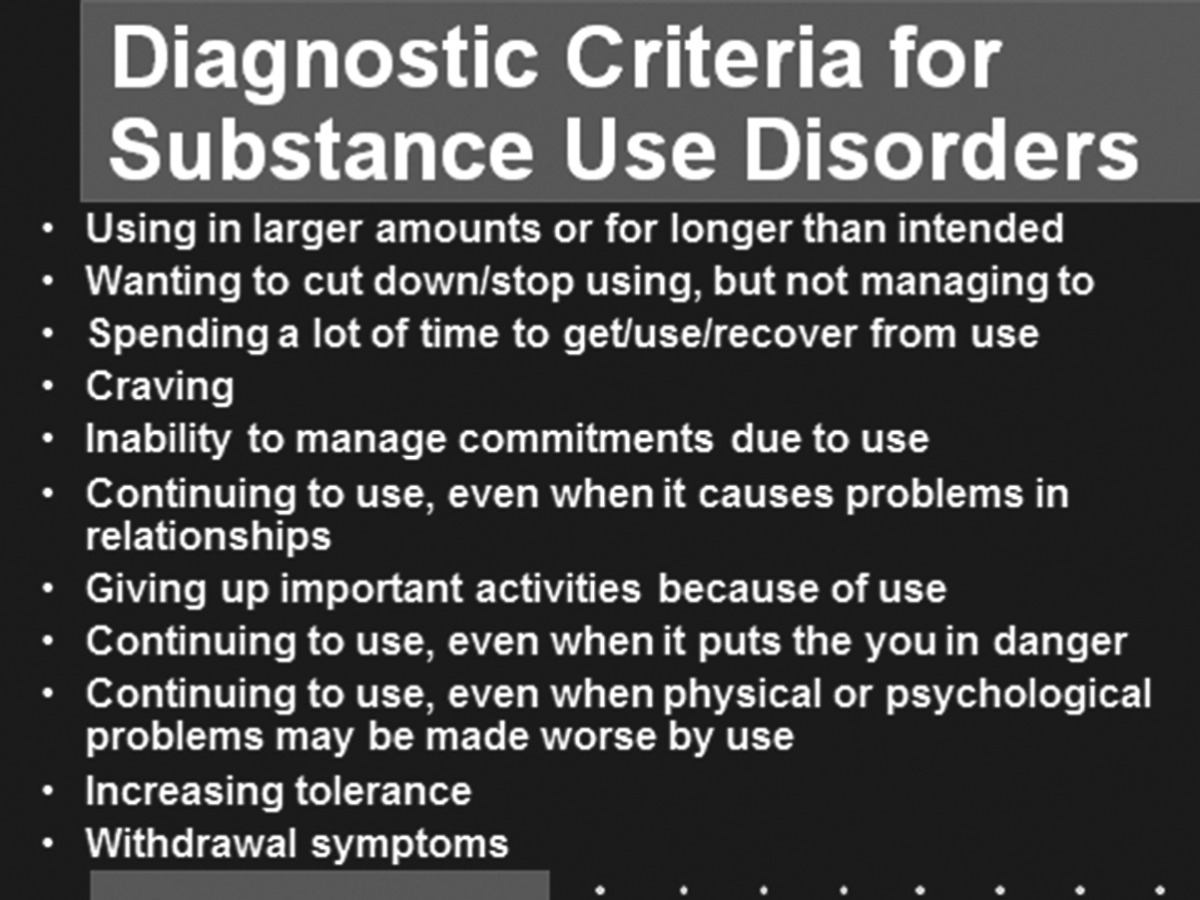

The current diagnostic criteria (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th Edition) listed in Table 2 include 11, equally weighted symptoms, generally related to “loss of behavioral control” — the cardinal feature of addiction (26). Individuals with fewer than two symptoms are not considered to have a disorder, although they may have had at least one misuse problem. Those exhibiting two to three symptoms are considered to have a “mild” disorder, four to five symptoms constitute a “moderate” disorder, and six or more symptoms is considered a “severe” substance use disorder — commonly called addiction (26). These criterial are likely to reduce the all-or-none thinking (i.e., addicted or not addicted) that has characterized clinical approaches in this field.

TABLE 2.

DSM 5 Criteria for Diagnosing Substance Use Disordersa

|

Fewer than 2 symptoms = no disorder; 2-3 = mild disorder; 4-5 = moderate disorder; 6 or more = severe disorder.

Two diagnosis-related points are particularly clinically relevant. Whereas tolerance and withdrawal remain major clinical symptoms, they are no longer the deciding factor in whether an individual has an addiction. Loss of control over use can occur with all substances discussed above (including marijuana), not just those that are able to produce tolerance and withdrawal. Second, because substance use disorders develop over time, with repeated episodes of misuse, it is both possible and highly advisable to identify emerging substance use disorders while they are mild or moderate, and to use evidence-based early interventions to stop the addiction process before the disorder becomes more chronic, complex, and difficult to treat.

This type of proactive screening and clinical monitoring is already done within general healthcare settings to address other potentially progressive illnesses that are brought about by unhealthy behaviors (27). For example, patients who show elevated but sub-threshold blood pressure readings as part of routine screening in primary care are typically asked to increase physical activity, change diet, and offered guidance on stress management as well as family education to provide support with lifestyle change. Typically, such cases are also provided telephone and in-person monitoring of key symptoms to assure that symptoms do not worsen.

There is also evidence that such an approach will improve the effectiveness of treatments for substance use disorders by treating them earlier in their onset. Early symptoms of a use disorder (especially among those with known risk and few protective factors) should occasion clinical guidance on how to reduce the frequency and amount of substance use, family education to support lifestyle changes, and regular telephone and in-person monitoring to prevent the escalation of the behavior to a disorder.

For more severe cases of frank addiction, remission and full recovery are now expectable results if evidence-based care is provided for adequate periods of time by properly trained clinicians augmented by supportive monitoring, recovery support services, and social services. This fact is evidenced by a national survey showing that more than 23 million previously diagnosed adults (about 10% of the adult population) identify themselves as being in stable recovery (28).

Unfortunately, substance use disorders have never been insured, treated, monitored, or managed like other chronic illnesses. Such care management strategies are possible thanks to the development of many evidence-based behavioral interventions, medications, clinical monitoring systems, and recovery support services that will make this type of chronic care management possible — likely by the same healthcare teams that currently treat other chronic illnesses (29).

WHY HAVEN’T SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS BEEN PART OF GENERAL HEALTHCARE?

Until recently, substance misuse problems and substance use disorders have been viewed as personal, family, or social problems, best managed at the individual and family levels, sometimes through the existing social infrastructure (school, places of worship, etc.) and when necessary through civil and criminal justice interventions (30). In the 1970s, when a significant proportion of college students and returning Vietnam veterans became addicted, most families and traditional social services were not prepared and arrests and other forms of punishment were not politically viable (31). Despite a compelling national need for treatment, the existing healthcare system was neither trained, nor especially eager to accept patients with substance use disorders.

For these reasons, a new system of addiction treatment programs was created, but with administration, regulation, and financing purposely placed outside mainstream healthcare (30,31). This meant that, with the exception of hospital-based detoxification, virtually all treatment was delivered by programs that were geographically, financially, culturally, and organizationally separate from mainstream healthcare. Of equal historical importance was the policy decision to focus treatment only on individuals with serious addiction. This left few provisions for detecting or intervening clinically with the far more prevalent cases of early-onset, mild, or moderate substance use disorders. The creation of this system of addiction treatment programs was a critical policy step toward addressing the burgeoning substance use problems. However, as indicated throughout this paper, that separation also created unintended and enduring impediments to the quality and range of care options for patients in both these segregated systems. For example, within general healthcare, efforts to reduce the costs of hospital stays and surgical procedures led insurers to increase pharmacy benefits to stimulate discovery of new medications. In the addiction field, treatment was already inexpensive, there were far fewer physicians providing care, and there were no pharmacy benefits. Consequently, until the 1990s, there were few medications to treat addictions (32).

RECENT CHANGES IN HEALTHCARE POLICY AND LAW

The longstanding segregation of substance use disorders from the rest of healthcare began to change with enactment of the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (the Parity act) and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 (33,34). When fully implemented, the ACA will require the majority of U.S. health plans and healthcare organizations to offer prevention, screening, brief interventions, and other forms of treatment for substance use disorders. Also, these two acts mandate that insurance coverage for substance use disorders must have generally the same scope and require no greater patient financial burden than the coverage currently available to patients with comparable physical illnesses, such as diabetes (34).

It is hard to overstate the importance of these two acts for creating a public health-oriented approach to reducing substance use problems and disorders. These changes are likely to move the treatment of substance use disorders into many of the same places where other illnesses are treated (e.g., primary care clinics), and likely by many of the same health care professionals. Recent changes in healthcare financing are incentivizing healthcare organizations to address important issues of integrating general healthcare with traditional addiction treatment.

Many questions remain but those questions relate to how — not whether — this much-needed integration will occur. In turn, these questions about integration will create a new and challenging but exceptionally promising era for the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders. However, because substance use disorders are so thoroughly intertwined with other medical conditions, the benefits from integration will extend more broadly in general healthcare by improving treatment success for other conditions, reducing hospital readmission, reducing the spread of infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis, and reducing drug-related accidents and overdoses. Indeed, a review by the Institute of Medicine has concluded: “It is not possible to deliver safe or adequate healthcare without simultaneous consideration of general health, mental health and substance use issues” (35).

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: Dr. McLellan is on the board of Indivior, makers of Suboxone, and has stock ownership in the company. He also received a grant in 1990 from Perdue Pharma to track the spread of Oxycontin abuse.

DISCUSSION

Dale, Seattle: Thank you Tom...I am sure there are some questions but I will ask the first one.... when will the Surgeon General’s report be done?

McLellan, Sarasota: The Surgeon General’s report is done and will be formally released November 17th.

Dale, Seattle: Just after the election.

McLellan, Sarasota: Yes, purposely after the election.... if the Surgeon General doesn’t leave office with the administration, he continues until July of next year.

Hughes, Chapel Hill: I’m a diabetes doctor and I was very struck by your presentation. Are we really taking serious drug abuse and now not categorizing it as dangerous?

McLellan, Sarasota: That’s a very interesting proposal and it’s under lots of discussion. In the last diagnostic change in DSM-5 there was question of whether you think of this as loss of rewards sensitivity. You might say internet use, pornography, sex addiction, shopping, etc....they all could be, if we knew the underlying physiology, they could be manifestations of reward control loss. We don’t know that yet. We know about substances because we can track their effects on various places in the brain. I assume we will be able to do that pretty soon with other kinds of these illnesses but that’s to come. I’ll make one more point: I think there is almost nothing about diabetes that isn’t true for addiction. I think the nature of its onset, and that it’s a generic and an acquired illness. There is no doubt about that. You basically eat your way into diabetes. You use your way into addiction. That has been something that’s always been the shibboleth that everybody said: “Well they brought on themselves.” Yes, they did. They brought it on themselves; they brought it on themselves when they were 14 to 18 years of age with a developing brain and they were very sensitive to it because their grandfather and father and uncle were carrying a gene.

Hochberg, Baltimore: So I have two questions: so first is can you comment on the expanded problem we have or may have because of legalization of marijuana? And then can you comment on prevention? How can we prevent this in our patients and our own children and grandchildren who are either in and out of adolescence or in young adults?

McLellan, Sarasota: I will and thank you for the easy question. So, as to marijuana, here’s my view: This is my opinion but it’s based on math. You saw that pyramid: Users, misusers, addicted.... now if you make any substance, Hershey bars, iPhones, whatever.... more available, cheaper — you’re going to have more people who use. That’s modern marketing. Then you heard about the genetic predisposition that you could have to addiction. So, among those users once you get more users, math sets in, and 10% roughly are going to become addicted. Not immediately but over time; but in addition, along the way, misuse is going to be associated deaths from highway accidents. It’s going to be associated with lots of other accidents, injuries, problems along the way. So I am not for expanded use of a legalization of marijuana and here’s why: We could talk all day long about how bad marijuana is for you; is it really any worse than alcohol? Good argument that it’s no worse than alcohol as a matter of fact — but that’s a stupid argument. The real argument is: is it any good for you? We have kids that are dropping out of school, they can’t meet math requirements, they are not competitive in work. Oh I know, make marijuana more available that’ll give them energy, interest, you know, real passion for life. So you know where I stand on that one. As to medical marijuana it is a fact that there are many substances that have really powerful useful medical uses. But the bark of the willow tree has an acetyl salicylic acid in it too. You don’t smoke the bark of the willow tree in order to get aspirin. You extract those elements, put them through FDA procedures because we have the safest medications in the world and let’s get some of those medications. Prevention works. Prevention is very badly used in this country because once again it was not understood. You probably had drug prevention in high schools, probably eighth grade and they gave you the “Drugs Are Bad” talk...okay box checked. Now, we know that the adolescent period is the continuous period of that risk. Not one point during adolescence, but from 12 to 25, so they’re always going to be at risk like you are when you go outside and you’re at risk for sunburn, so our responsible mother doesn’t say, “Tom stay out of the sun, are we clear about this? You’re going to get skin cancer.” Okay box checked, no! You get slathered with sunblock all the time so the most effective prevention programs are now community oriented. Community because you combine all the influences that the hit a kid at school: the parent, the church, the community. Also they are generic. We do not need a methamphetamine prevention program, a marijuana prevention program, an obesity, a bullying program. We do not need those because the risk factors are all the same. The harms that are killing and hurting our children are quite comparable across all those things. Moreover, things that reduce those harms are quite comparable so you need bigger, fatter, richer, more protracted continuing care prevention. Does anything like that exist? Yes, there are many studies, most recent one done in Pennsylvania — 26 communities, randomly assigned to get that kind of preventive care versus the 26 communities who got educated but nothing more. You saw 40% and higher reductions in the prevention communities in things like school dropouts, substance use, cigarette use, alcohol binge drinking, teenage pregnancy.... every damn thing you don’t want to see happen to your grandkid so that’s the way to do it.... we just don’t have the infrastructure to do it.

Pasche, Winston Salem: I think your talk really resonates with many of us with either children or grandchildren. In our case our child — we are being surprised to see how much substance abuse there is already at high school and you mentioned the issue of the colleges. They are actually experimental labs where additional substance use is supported or I would say tolerated — as most of us work with the medical school that are affiliated with colleges. Isn’t that the right time to have a call for action where actually the medical community should intervene at the level of colleges where probably intervention or at least screening could be applied on a larger scale than it is now?

McLellan, Sarasota: Yes, I agree with your comments...the nature of them. Moreover, and this is very important....no doctor. Nobody wants to take off on a crusade for something that is not going to work. But prevention stuff works! When colleges institute early intervention and prevention programs, the high schools do that, kids talk about their substance use. They circulate messages about how to avoid overdose and things like that and it reduces the prevalence of these kinds of problems. It isn’t the problem with prevention in these early interventions, it’s everybody’s and nobody’s job. All the parents are saying, “I just wish my primary care doctor would do something about substance use.” And the primary care doctor is saying, “I wish those clergies would speak at church and talk about reducing.” And the clergy are saying, “I wish these parents were more responsible.” The truth is, everybody has got to do a little bit and they must understand this, and they have to be vigilant. And then it can work.

Gotto, New York City: I got a couple of questions: the first one is, do you have any data on the success of 12-step programs?

McLellan, Sarasota: Yes, 12-step programs have been the only thing available in modern times. There are many 12-step programs, for those of you who don’t know, including AA, Smart Recovery, Women in Recovery. They are free, they are available. I am sure there is an AA meeting somewhere in this town twice today. They are fundamentally sound, they have been evaluated and randomized control trials and they work but they work like a gym works. You know, I was a member for years in a gym very close to my office. Well it turns out you have to go and you have to make the iron go up and down otherwise it doesn’t work. So who knew! I thought I just had a membership. No you must go and the same is true for AA. For people who go, it has been the most reliable way in getting into recovery, but it only affects about 10% of the population and that means 90% want other things. They want medications. Perhaps, they want behavioral therapies. Perhaps, they want other things and they haven’t been made available. So I am not one that denigrates AA. It’s just not enough. I don’t know, it’s like diet in diabetes. That will do something for a certain set of people if they are religious about it. But it’s not for everybody.

Gotto, New York City: My second question has to do with diabetes.... I think you need to make a distinction between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. I realize that the origins of type 1 diabetes are complex. In one Scandinavian study with identical twins, only about half of them developed diabetes. And with the onset of adolescent obesity, you are seeing type 1 diabetics develop. But to imply that a child of 5 or 6 years, who develops diabetes, has brought it on themselves, is offensive to the child and the family. So we must make distinctions between type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

McLellan, Sarasota: Yes, that’s a fair point. I would simply extend it. I say the same thing about addiction. Most kids are getting addicted before they’re legally able to drive a car. Their brains aren’t developed, but that’s when things are happening, so yes they’ve brought it on themselves I was very interested in this guy who — he tried to blow up New York the other day, and they caught him and he was, I think, he was shot. Well, you know, the first place they took him was the hospital to treat him. Now, he brought that on himself did he not? He is a criminal, is he not? And yet he got treatment unquestioned. I’ve heard it all my life, “Addicts, actually, it’s better that they don’t get treatment — they brought it on themselves and they should work it out.” It’s just antiquated thinking.

Baum, New York City: Would you say a few words about buprenorphine and methadone?

McLellan, Sarasota: Yes, I will.... I should first say that I am on the Board of Indivior, which makes Suboxone. Methadone is a synthetic opioid agonist....it acts for 24 to 48 hours, very potent, and the way it acts is by substituting an oral controllable opioid addiction or an IV heroin addiction. Medicated right, methadone will not make the person high but it will take away withdrawal symptoms and it will do so in a gradual manner and will taper down over of the 24-hour period. There are at least 2,000 studies showing that methadone maintenance reduces IV drug use, it improves employment, improves health. All that, but they still are addicted. So if I would never say that this is your first line of treatment. Suboxone (buprenorphine) is a partial agonist and it has almost all the same properties of methadone or any other long acting orally administered opioid but it has one very important safety feature, because it’s a partial agonist you can’t get the same level of respiratory depression and then some of the other cardiac symptoms that you get with full opioid agonist and therefore it’s a safer alternative. But you are still dependent upon a prescribed opioid so once again it’s a decision. Again, like diabetes, if you can take a person who is at risk for diabetes and through dietary control and exercise, personal management, prevent them from ever going insulin you’re very wise to do that. If they can’t, won’t, whatever, you’re crazy if you don’t give them the medication that will save their lives. So this has been an issue for 30 years in addiction.

Balser, Nashville: You’re talking a little bit about AA and the 12-step program and for many, many people that’s a critical part of chronic care. The thing I run into is increasingly having millennials and the younger generation who are agnostic and because so much of the AA model is wrapped into religious beliefs and that worked pretty well for our generation. What people are finding is that going to medical facilities where the care model is very much tied to AA, they are very uncomfortable. And I am wondering if that is a recognized issue and whether there are other models that are developing that we can point people to who just are not comfortable with that kind of chronic care model.

McLellan, Sarasota: Well, good point, and I would agree. Please don’t hear me say: everybody ought to go to AA. They shouldn’t, everybody shouldn’t get insulin. But what is needed are alternatives for people. If you don’t like AA, then let’s get something else and there are. There are depending upon the substance use problems. There are very effective behavioral therapies: individual or group. Family therapies are among the most effective. There are medications for alcohol and opioid but not methamphetamine, marijuana, or cocaine. So there are other things you can do. But here’s the other thing about AA, if a person hasn’t, doesn’t like AA, go to another meeting. If you’ve seen one AA meeting you’ve seen one.... They’re all over the place. There are AA meetings that simply cater to gay and lesbians. There are AA meetings that cater to Yale graduates, seriously...in Philadelphia! Full by the way. There are AA meetings for people who are being medicated for psychiatric illness. So, there are lots of them.... And the AA directory points them out. The best thing to do is try them out.

Wolliscroft, Ann Arbor: You mentioned the importance of community, family. There’s also a proliferation of apps and internet interventions. Could you comment if there is any data or any utility analysis?

McLellan, Sarasota: I, as Dr. Dale said, am an expert in addiction.... I studied this my whole life.... I worked on it and I worked in a facility where I am surrounded by experts. But when my kid needed addiction help, I didn’t know anything. I didn’t know any of the fundamental questions like the one that you are talking about.... when you go into the internet today, it is predominantly inaccurate information. And that is not my opinion; my old organization just did a website analysis. They went through — did all the search terms for prevention and treatment of every addiction and they culled the many thousands of websites. About 80% contained absolutely inaccurate, false, misleading, sometimes dangerous information. So that organization is trying to develop a curated website so that when you’re in this situation where you want to prevent — you’re worried about your kid or your grandkid or you need treatment, it’s like shopping for a funeral. You’re emotionally charged, you don’t know what the hell to do. You can’t talk to your friends about it because you are ashamed. So you turn to places like this and there isn’t information. We need more consumer education and that is one of the reasons the Surgeon General’s report is so important. Because I think people are going to finally understand what can work through science, and what will be available to them. They will have the political information necessary to demand that kind of high quality prevention, early intervention, treatment, and maybe we will be able to get much better quality.

Luke, Cincinnati: Where by the way we have a real epidemic (McLellan: yes, you do).... My question is about prevention. I have memories of a tobacco company national campaign. The one that still strikes me is the man with emphysema trying to get a cigarette. Can we scare the kids a little more by showing the effects with that approach....it certainly seemed to work with tobacco.

McLellan, Sarasota: So, I can talk to you a little bit about that.... There has been The Partnership for Drug Free Kids. Very famously it had that advertisement: “This is your brain, this is your brain on drugs.” The fried egg.... It’s still one of the most recognized ads ever. It had no impact at all! So later on during the hype of the methamphetamine crisis — a wealthy guy who manufactures medical equipment said: “You know what? I want do this, I want to do this in Montana. And the reason it never worked before is that you didn’t scare them enough.” So, he created actual and accurate pictures of young girls, mostly who would have been young sweet looking cheerleaders and literally a year later they looked like the Grimm brother’s characterization of a witch. Methamphetamine constricts all capillaries, especially around your mouth.... you get this thing called meth-mouth where their teeth fall out and they’re haggard and awful looking....and he put it all over Montana. But methamphetamine use increased. So, I don’t understand why that doesn’t work but it does not appear to work......In contrast, the information which is put out to cut smoking seems to work very, very well.

Hook, Birmingham: I am going back to some of your initial comments about the great success of tobacco cessation efforts nationally. But tobacco abuse is a global problem and it’s the U.S. companies that continue to catalyze and push global tobacco use and abuse. As I begin to think about issues related to substance abuse, I wonder about the global parameters of substance abuse since our world is shrinking as we move more and more.

McLellan, Sarasota: Yeah, you’re right to worry. A recent work, characterized pretty accurately, that the first crops ever created were designed to ferment. So, it is really in our DNA to get high. And it’s a world problem. The United States does not have the worst problem but we’re right up there. To me, I think it would be naïve to imagine that you could eradicate addiction. But you can do things to stop misuse and with it the many, many, many hundreds of thousands of unfortunate casualties. We can do a lot better with the disease of addiction. And along the way I’m quite certain of this, it will improve overall healthcare. It will reduce the costs of overall healthcare, and improve the quality. So, I think the benefit of this, particularly for an audience like this, is not just that it’s time to do something for the addict — yes it is — but the gift here is going to be for mainstream healthcare. That $120 billion dollars is a big ticket to pay for willful ignorance about something that hits 20% of every practice that is represented in this room.

Wolf, Boston: In terms of why meth-mouth didn’t work, about 50 or 60 years ago a group at Yale set up three tents at a fair, one said: “You shouldn’t smoke it’s bad for your health.” One showed people with advanced stage lung cancer, and one gave information. The one with the photos of terrible appearing patients didn’t work at all. I think that there is denial. If it’s too scary it doesn’t work.

McLellan, Sarasota: I’ve talked to people who deal with stroke and heart vascular illness that denial is a very big part of their illness.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, et al. 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. Am J Prevent Med. 2015;49((5)):e73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Drug Intelligence Center. National drug threat assessment. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2011. Available at: www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Rethinking drinking. Available at: http://rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/How-much-is-too-much/Is-your-drinking-pattern-risky/Whats-Low-Risk-Drinking.aspx. Accessed September 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Excessive drinking costs US $249 billion. 2014. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26477807/ Accessed September 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott KM, Lim C, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, et al. Association of mental disorders with subsequent chronic physical conditions: world mental health surveys from 17 countries. JAMA Psychiatr. 2016;73((2)):150–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldstein BI. Recent progress in understanding pediatric bipolar disorder. Archives of Pediatr AdolescMed. 2012;166((4)):362–71. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grodensky CA, Golin CE, Ochtera RD, Turner BJ. Systematic review: effect of alcohol intake on adherence to outpatient medication regimens for chronic diseases. J Studies Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73((6)):899–910. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford JD, Trestman RL, Steinberg K, Tennen H, et al. Prospective association of anxiety, depressive, and addictive disorders with high utilization of primary, specialty and emergency medical care. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58((11)):2145–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol poisoning deaths. Vital signs: alcohol poisoning kills six people each day. 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/media/dpk/2015/dpk-vs-alcohol-poisoning.html. Accessed September 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, US, 2007–2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49((3)):409–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Volkow ND, McLellan TA, Cotto JH, Karithanom M, et al. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions in 2009. JAMA. 2011;305((13)):1299–301. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. The DAWN Report: Highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) findings on drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville, MD: 2013. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/emergency-department-data-dawn. Accessed September 25, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbel JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths — United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortality Wkly Rep. 2016;64((50)):1378–82. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6450a3.htm. Accessed September 25, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain — United States. MMWRMorb Mort Wkly Rep. 2016;65((1)):1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldman D, Oroszi G, Ducci F. The genetics of addictions: uncovering the genes. Nat Rev Gen. 2005;6((7)):521–32. doi: 10.1038/nrg1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychol Bull. 1992;112((1)):64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, et al. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: data from a national sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68((1)):19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayberry ML, Espelage DL, Koenig B. Multilevel modeling of direct effects and interactions of peers, parents, school, and community influences on adolescent substance use. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38((8)):1038–49. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marschall-Lévesque S, Castellanos-Ryan N, Vitaro F, Séguin JR. Moderators of the association between peer and target adolescent substance use. Addictive Beh. 2014;39((1)):48–70. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2005;62((6)):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanson KL, Medina KL, Padula CB, Tapert SF, et al. Impact of adolescent alcohol and drug use on neuropsychological functioning in young adulthood: 10-year outcomes. J Child Adolesc Substance Abuse. 2011;20((2)):135–54. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2011.555272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanson KL, Medina KL, Padula CB, Tapert SF, et al. Impact of adolescent alcohol and drug use on neuropsychological functioning in young adulthood: 10-year outcomes. J Child Adolesc Substance Abuse. 2011;20((2)):135–54. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2011.555272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, Castellanos FX, et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2((10)):861–3. doi: 10.1038/13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Squeglia LM, Tapert SF, Sullivan EV, Jacobus J, et al. Brain development in heavy-drinking adolescents. Am J Psychiatr. 2015;172((6)):532–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14101249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (5th ed.) Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288((15)):1909–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feliz J. Survey: Ten Percent of American Adults Report Being in Recovery From Substance Abuse or Addiction. New York, NY: Partnership for Drug Free Kids; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General; 2016. Nov, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White W. Slaying the Dragon: The history of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America. (2nd Ed.) Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musto DF. The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1987. (Expanded ed.) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rettig RA, Yarmolinsky A. Federal Regulation of Methadone Treatment. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001. Public Law 111–148. 2010. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf. Accessed September 25, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. Final Rules [78] Federal Register [219] 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]