Abstract

Severe systemic hypertension can cause significant damage to the eye. Although hypertensive retinopathy is a well-known complication, hypertensive optic neuropathy and hypertensive choroidopathy are much less common. The aim of this article is to report an unusual case of hypertensive choroidopathy with bullous exudative retinal detachments in both eyes. The retinal detachments spontaneously resolved after blood pressure was controlled. However, multiple large retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) rips were found in both eyes. These RPE rips may be related to severe choroidal ischemia, and their locations may be compatible with the watershed zones of the choroidal perfusions.

Keywords: exudative retinal detachment, hypertensive choroidopathy, retinal pigment epithelial rip

1. Introduction

Severe systemic hypertension can cause significant end-organ damage.1 One of the commonly involved organs is the eye. Although hypertensive retinopathy is a well-known complication, hypertensive optic neuropathy and hypertensive choroidopathy are much less common. Hypertensive choroidopathy has been reported in patients with toxemia of pregnancy, renal disease, pheochro-mocytoma, and malignant hypertension.2 The manifestations of hypertensive choroidopathy may include exudative retinal detachment, retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) detachment, Elschnig spots, and Siegrist's streaks.3,4,5

The retinal pigment epithelium is a single layer of low columnar epithelial cells. It forms the outermost layer of the retina and is separated from the choroid by Bruch's membrane. RPE rips were first described by Hoskin et al.6 They are commonly related to age-related macular degeneration and choroidal neovascularization (CNV).6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 They may occur in patients who have received laser photocoagulation,9,10 photodynamic therapy,11 or intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injection.12,13,14 RPE rips without CNV are rare. Other etiologies include VogteKoyanagieHarada syndrome15 and central serous chorioretinopathy.16 Herein, we report an unusual case who developed multiple RPE rips in both eyes due to hypertensive choroidopathy. To our knowledge, this is the irst case report regarding this unusual presentation in hypertensive patients. We also discuss the possible mechanisms.

2. Case presentation

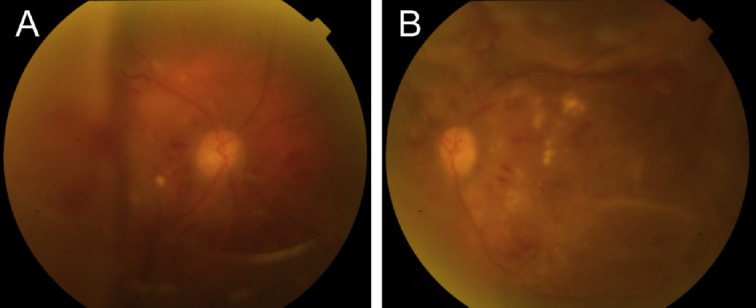

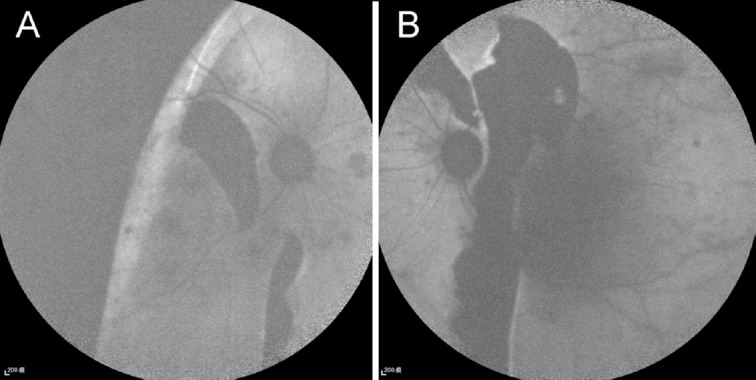

A 59-year-old female patient visited our hospital because of painless visual loss in her right eye for 1 month and an enlarging black shadow in her left eye for 2 days. She had hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and end-stage kidney disease under hemodialysis. Her blood pressure was 206/125 mmHg in our outpatient clinic. Her visual acuity was 1/100 in both eyes. Intraocular pressure was 11 mmHg in the right eye and 10 mmHg in the left. Anterior segments were essentially normal except for a moderate cataract in both eyes. B-scan echography showed bullous exudative retinal detachment in both eyes (Figure 1). Indirect ophthalmoscopy examination also found diffuse retinal arteriolar narrowing, increased vascular tortuosity, multiple dot and blot retinal hemorrhages, macular exudations, and subtotal bullous retinal detachments in both eyes (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with proliferative diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema, and hypertensive choroidopathy. The patient was referred to the internal medicine department for blood pressure control. The exudative retinal detachments gradually resolved 1 week after hypertension control. However, there was no improvement of visual acuity in both eyes. Fundus autofluorescence (Figure 3), second color fundus photography, fluorescein angiography, and indocyanine green angiography (Figure 4) were performed 2 weeks after initial presentation. Large RPE rips were found in color fundus photos of both eyes (Figure 4). Fundus autofluorescence of the right eye showed a large area of hypoautofluorescence at the temporal quadrants, the papillomacular area, and the inferior side of the optic disc (Figure 3A). Fundus autofluorescence of the left eye showed hypoautofluorescent areas at the superior side of the disc and at the papillomacular area vertically extending to the inferior side of the disc (Figure 3B). These hypoautofluorescent areas corresponded to the RPE defects on the color fundus photos. Hyperfluorescent lines could be identified at the margin of the hypoautofluorescent areas, possibly caused by the rolling of the RPE layer. Multiple sharply defined hyperfluorescent areas appeared at the early phase of fluorescein angiography and did not change in size or shape during the entire examination (Figure 4). These hyperfluorescent areas corresponded to the increased fluorescence transmission from the RPE defects. Increased visibility of choroidal vessels was also noted in these areas in the early phase of indocyanine green angiography (Figure 4). Moreover, large areas of retinal capillary nonperfusion and multiple retinal neovascularizations in both eyes were found on fluorescein angiography. Optical coherence tomography showed RPE defects and severe bilateral macular edema in both eyes (Figure 5). The patient received an intravitreal injection of bevacizumab 1.25 mg/0.05 mL in her right eye at 2 months. The macular edema in the right eye improved after treatment. Visual acuity of the right eye improved to 1/32. There was no change in visual acuity in her left eye. The patient refused further treatments because of unsatisfactory visual improvements.

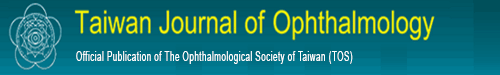

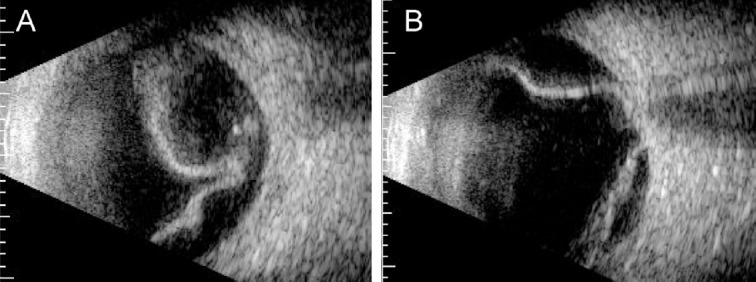

Figure 1.

B-scan echography at initial presentation showed bullous retina detachment in (A) the right eye and (B) the left eye.

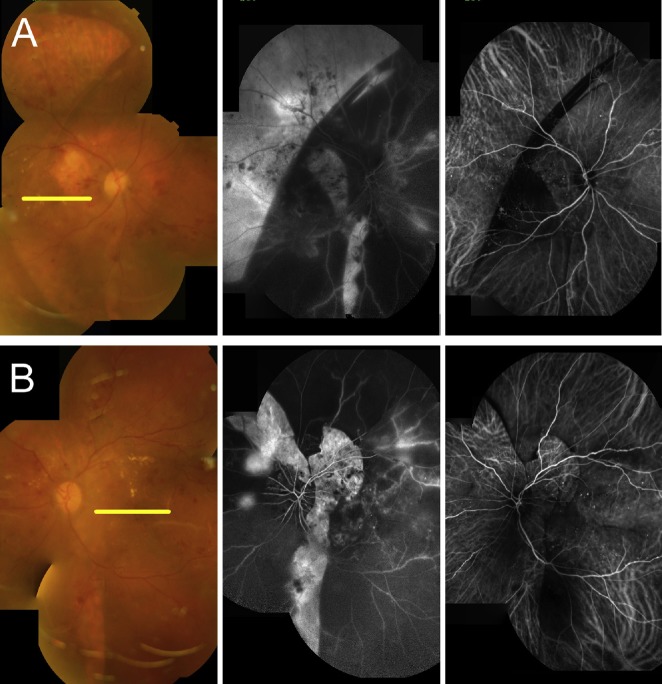

Figure 2.

Color fundus photos at initial presentation showed bullous retinal detachments in (A) the right eye and (B) the left eye. Diffuse retinal arteriolar narrowing, increased vascular tortuosity, multiple dot and blot retinal hemorrhages, and macular exudations could also be found in both eyes.

Figure 3.

Fundus autofluorescence 2 weeks after initial presentation when the exudative retinal detachments resolved in both eyes. (A) Fundus autofluorescence of the right eye shows a large area of hypoautofluorescence at the temporal quadrants, the papillomacular area, and the inferior side of the optic disc. (B) Fundus autofluorescence of the left eye shows a hypoautofluorescent area at the superior side of the disc and at the papillomacular area vertically extending to the inferior side of the disc. These hypoautofluorescent areas correspond to the retinal pigment epithelial defects. Hyperfluorescent lines can be identified at the margin of the hypoautofluorescent areas.

Figure 4.

Comparison of color fundus photos (left), fluorescein angiographies (middle), and indocyanine green angiographies (right) 2 weeks after initial presentation. (A) A large RPE defect can be found at the temporal quadrants of the right eye. Vertical RPE defects can be found at the temporal and inferior sides of the optic disc. (B) RPE defects can be found at the superior and temporal sides of the optic disc. The RPE defects correspond to the sharply defined hyperfluorescent areas on the fluorescein angiography and the increased visibility of choroidal vessels on the indocyanine green angiography. RPE = retinal pigment epithelial.

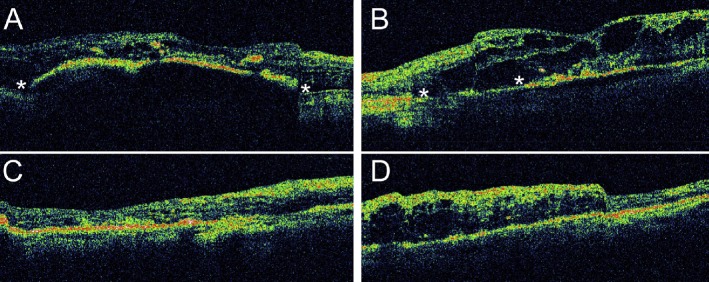

Figure 5.

OCT of (A) the right eye and (B) the left eye 2 weeks after initial presentation. The corresponding locations of the scans are marked in the color fundus photos in Figure 4. Asterisks (*) indicate the locations of the RPE defects. Intraretinal fluid and exudates can be found in both eyes. OCT of (C) the right eye and (D) the left eye 3 months after initial presentation. The macular edema in the right eye improved after an intravitreal injection of bevacizumab. The left eye received no treatment, and its macular edema persisted. OCT = optical coherence tomography; RPE = retinal pigment epithelial.

3. Discussion

The choroidal vasculature is characterized by short and scarcely branching arteries.2,17,18 The fact that blood supply enters the choriocapillaris at right angles and causes blood pressure to be transmitted more directly to the choriocapillaris may contribute to susceptibility to choroidal vasculature damage in acute blood pressure elevation.2,17,18 Hayreh et al19 proposed a pathogenesis of hypertensive choroidopathy. In accelerated hypertension, the acute rise in blood pressure transmitted directly to the choroid. Although the choroidal vascular bed in humans has a rich autonomic nerve supply, it is not autoregulated. Furthermore, there are large fenes-trations in the walls of the choriocapillaris, so the choroidal vascular bed has no blood–ocular barrier. This causes leakage of plasma into the choroidal fluid. Angiotensin II and other vasoconstrictors in the choroidal fluid result in vasoconstriction and ischemia of the choroidal vasculature. This cascade is followed by RPE ischemia and the subsequent breakdown of the blood–retinal barrier in the RPE. An animal study also revealed the substantial depletion of occludin, a tight-junction protein, in the RPE of ischemic mice. These results support the hypothesis of the ischemia-induced breakdown of tight junctions in the RPE.20 Thus, hypertensive choroidopathy may lead to exudative retinal detachment in severe cases.21 Our patient had bullous subtotal exudative retinal detachment in both eyes. This may imply a profound choroidal ischemia and severe breakdown of the blood–retinal barrier in the RPE.

RPE rips are commonly related to CNV with or without treatment.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 The exact mechanism is still unclear. Nagiel et al14 suggested that the rapid involution and contraction of neo-vascular tissue adherent to the undersurface of the RPE may produce a substantial contractile force, leading to rips in these patients. However, this hypothesis may not be able to explain the RPE rips in our patient because no CNV was found in either eye. In our patient, the bullous exudative retinal detachment gradually resolved after blood pressure was controlled. It is unknown whether the rapid decompression of the RPE detachment after the blood pressure drop could have caused the RPE rips in this patient. Alternatively, the RPE rips could be a result of extensive RPE damage due to severe ibrinoid necrosis.

In accelerated hypertension, ibrinoid necrosis develops with the occlusion of choroidal arterioles and segmental infarction of the choriocapillaris.22 This may lead to the death of the overlying RPE and photoreceptors.23 Clinically, areas of the RPE overlying the occluded choriocapillaris appear yellow (Elschnig spots) and leak fluorescein dye profusely in the acute stage. These spots become hyperpigmented with a margin of hypopigmentation at the late stage.24 Occasionally, hyperplasia of the RPE appears over affected choroidal arteries as a linear coniguration of hyperpigmentation (Siegrist's streaks).3 Apart from hypertension, our patient had poorly controlled diabetes mellitus and end-stage renal disease. These comorbid medical disorders may also increase the vulnerability of choroidal vessels and result in more severe choroidal ischemia in our patient. Thus, the multiple RPE rips in our patient may be related to more severe choroidal ischemia and more extensive ibrinoid necrosis of the choroidal vessels.

Except for the large RPE rips at the temporal quadrant in the right eye, all RPE rips in both eyes could be found in the peri-papillary areas. This may be correlated to the distribution of choroidal blood supply. The choroid, RPE, and outer retina are supplied by various (1–5) posterior ciliary arteries (PCAs).17 Hayreh et al17 demonstrated that in vivo, the vascular pattern of PCAs and their branches down to the terminal arterioles is strictly segmental, with no anastomoses between the adjacent vascular segments. The watershed zones of medial PCAs and lateral PCAs are usually located around the optic nerve head and extend vertically.17 The RPE rips around the optic discs in our patient may correspond to the watershed zones of PCAs, which were more vulnerable to the choroidal ischemia. The large RPE rips at the temporal quadrant in the right eye may also correspond to the watershed zones of lateral PCAs and long PCAs. Interestingly, we could not clearly identify the watershed zone in our fluorescein angiography and indocyanine green angiography images. It is possible that these angiographic images were taken 2 weeks after initial presentation. The blood pressure was under appropriate medical control, and the systemic hemodynamic status could already return to normal. The choroidal ischemia and watershed zones might be dificult to observe at this stage.

In conclusion, we have reported an unusual case of hypertensive choroidopathy with multiple large RPE rips in both eyes. These RPE rips may be related to severe choroidal ischemia, and their locations may be compatible with the watershed zones of the choroidal perfusions.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: There is no conflict of interest for all authors.

References

- 1.Ugarte M, Horgan S, Rassam S, Leong T, Kon CH. Hypertensive choroidopathy: recognizing clinically significant end-organ damage. Acta Ophthalmologic. 2008;86:227–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tso MO, Jampol LM. Pathophysiology of hypertensive retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1132–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(82)34663-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puri P, Watson AP. Siegrist's streaks: a rare manifestation of hypertensive choroidopathy. Eye. 2001;15:233–234. doi: 10.1038/eye.2001.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song YS, Kinouchi R, Ishiko S, Fukui K, Yoshida A. Hypertensive choroidopathy with eclampsia viewed on spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. GraefesArch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:2647–2650. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2462-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dewilde E, Huygens M, Cools G, Van Calster J. Hypertensive choroidopathy in pre-eclampsia: two consecutive cases. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2014;45:343–346. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20140617-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoskin A, Bird AC, Sehmi K. Tears of detached retinal pigment epithelium. Br J Ophthalmol. 1981;65:417–422. doi: 10.1136/bjo.65.6.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendis R, Lois N. Fundus autofluorescence in patients with retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) tears: an in-vivo evaluation of RPE resurfacing. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252:1059–1063. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2549-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gass JD. Pathogenesis of tears of the retinal pigment epithelium. Br J Oph-thalmol. 1984;68:513–519. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.8.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gass JD. Retinal pigment epithelial rip during krypton red laser photocoagu-lation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;98:700–706. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(84)90684-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barondes MJ, Pagliarini S, Chisholm IH, Hamilton AM, Bird AC. Controlled trial of laser photocoagulation of pigment epithelial detachments in the elderly: 4 year review. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:5–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein M, Heilweil G, Barak A, Loewenstein A. Retinal pigment epithelial tear following photodynamic therapy for choroidal neovascularization secondary to AMD. Eye. 2005;19:1315–1324. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer CH, Mennel S, Schmidt JC, Kroll P. Acute retinal pigment epithelial tear following intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) injection for occult choroidal neovascularisation secondary to age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1207–1208. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.093732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carvounis PE, Kopel AC, Benz MS. Retinal pigment epithelium tears following ranibizumab for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:504–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagiel A, Freund KB, Spaide RF, Munch IC, Larsen M, Sarraf D. Mechanism of retinal pigment epithelium tear formation following intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy revealed by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156:981–988. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mili-Boussen I, Letaief I, Dridi H, Ouertani A. Bilateral retinal pigment epithelium tears in acute Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2013;7:350–354. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e3182964f68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim Z, Wong D. Retinal pigment epithelial rip associated with idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy. Eye. 2008;22:471–473. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6703020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayreh SS. Segmental nature of the choroidal vasculature. Br J Ophthalmol. 1975;59:631–648. doi: 10.1136/bjo.59.11.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torczynski E, Tso MO. The architecture of the choriocapillaris at the posterior pole. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;81:428–440. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(76)90298-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayreh SS. Posterior ciliary artery circulation in health and disease: the Weisenfeld lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:749–757. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu HZ, Le YZ. Signiicance of outer blood-retina barrier breakdown in diabetes and ischemia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2160–2164. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirano Y, Yasukawa T, Ogura Y. Bilateral serous retinal detachments associated with accelerated hypertensive choroidopathy. Int J Hypertens 2010. 2010 doi: 10.4061/2010/964513. 964513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DellaCroce JT, Vitale AT. Hypertension and the eye. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2008;19:493–498. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283129779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayreh SS, Servais GE, Virdi PS. Fundus lesions in malignant hypertension. VI. Hypertensive choroidopathy. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:1383–1400. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33554-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bourke K, Patel MR, Prisant LM, Marcus DM. Hypertensive choroidopathy. J Clin Hypertens. 2004;6:471–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.3749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]