Abstract

This study examined the perceptions of preparedness and support of informal caregivers of hospice oncology patients. Respondents included co-residing, proximate, and long distance caregivers. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data from two caregiver surveys, one administered prior to the care recipient’s death and another completed three months post-death. Respondents (N=69) interpreted “preparedness” broadly and identified multiple sources of support including hospice personnel, family, friends, neighbors, and spiritual beliefs. Additionally, informational support, such as education, information, and enhanced communication were considered essential for preparing and supporting caregivers. Implications for social work research and practice are provided.

Keywords: Death, dying, bereavement, family caregiving, perceptions

Introduction

An estimated 1.5 million new cancer cases, and more than half a million cancer deaths, were predicted for 2009 (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2009). Currently, cancer is surpassed only by heart disease as the nation’s leading cause of death (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). When conventional curative-focused cancer treatments, such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, are exhausted or declined, many individuals choose hospice, a form of palliative care that focuses on pain and symptom management at the end of life. An estimated 38.5% of all deaths in the U.S. occur while under hospice care (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization [NHPCO], 2009). During the transition to end-of-life care, family members and/or close friends often step into a caregiving role. Numerous researchers have explored the needs and experiences of these informal caregivers. However, our knowledge about this group remains incomplete (Herbert, Dang & Schulz, 2006; Herbert, Prigerson, Schulz & Arnold, 2006; Herbert, Schulz, Copeland & Arnold, 2009). In particular, the concept of caregiver preparedness and the specific types of support needed during end-of-life care are not fully understood.

We analyzed written responses to open-ended prompts on two self-report surveys, the first of which was administered to caregivers within the first week of admission into hospice service. The second was a post-death survey, administered three months after the patient’s death. The prompts inquired about how respondents could have been better prepared or supported during the care of their loved one. The qualitative data presented here are part of a larger study (Cagle, 2008) designed to better understand the transition from caregiving to bereavement, with particular attention to the geographic proximity of caregivers. Thus, the analysis also included responses from long distance caregivers about their care-related experiences, including their perceptions about distance and its impact on their ability to provide care.

Background

Over 4,800 hospices in the United States provide palliative care to an estimated 1.45 million patients annually (NHPCO, 2009). A majority (38%) of these patients are diagnosed with an advanced-stage malignancy (NHPCO, 2009). The overarching philosophy of hospice care is patient/family-centered, which allows individuals to direct their own care plans. For the vast majority of those receiving hospice services, a network of family members, friends, and neighbors provides the bulk of patient care.

Evidence suggests that caregivers of persons with cancer tend to experience high levels of burden (Emanuel et al., 2000; Emanuel, Fairclough, Slutsman, Alpert, Baldwin & Emanuel, 1999; Ferrario, Cardillo, Vicario, Balzarini & Zotti, 2004; Given et al., 2004). These informal care providers are also known to report lower quality of life (McMillan, 1996), greater relationship strain (Kissane, Bloch, Burns, McKenzie & Posterino, 1994), a decreased sense of mastery (Moody, Lowery & Yarandi cited in McMillan et al., 2006), and diminished mental and physical health (Haley et al., 2001; Nijober et al., 2000; Nijober et al., 1998). And perhaps most disconcertingly, Schulz and Beach (1999) reported that caring for a terminally-ill loved one can increase one’s own risk of mortality.

Providing care, however, can also be a rewarding experience (Amirkhanyan & Wolf, 2003; Boerner, Schulz & Horowitz, 2004), even when the care recipient has a life-limiting diagnosis (Aranda & Milne, 2000; Brown & Stetz, 1999; Nijober et al., 1998; Salmon, Kwak, Acquaviva, Brandt & Egan, 2005). Positive outcomes include feelings of personal growth, a sense of accomplishment, increased knowledge, reciprocity, and increased self-efficacy, preparedness, and empathy (Amirkhanyan & Wolf). Other positive changes may occur within the family system or caregiving network, such as strengthened relationships during the care process (Aranda & Milne; Brown & Stetz,).

The caregiving experience is more apt to be a positive experience if the caregiver has adequate physical, emotional, informational, and financial support -- in other words, feels prepared to meet the multiple demands of providing good care. Preparedness has a tangible dimension – knowing what to do – as well as an emotional dimension – being prepared to cope with the stressors and emotional demands of the role. Most find it “daunting at first,” (Foley et al., p. 242) but with time and support it can become more manageable. The most commonly expressed needs of care providers include psychological support, information, specific skills to provide appropriate care, assistance with household duties and daily living, and respite or relief from caregiving responsibilities (Foley, et al., 2005). The role of hospice and other formal caregivers is to provide the support, education, respite and other services so that the family/informal caregiver can manage their responsibilities.

Preparedness for death, as conceptualized by Herbert and colleagues (2006), includes medical, psychosocial, spiritual, and practical dimensions – dimensions that can be influenced by communication regarding end-of-life issues. Forewarning family members about a patient’s prognosis and the likely progression of an illness may allow them time to activate the necessary coping resources. For example, Barry, Kasl, and Prigerson (2002) found that subjective assessments of preparedness predicted complicated grief. Those who reported feeling less prepared were more likely to experience symptoms of psychiatric morbidity. However, Hansson and Strobe (2004) reviewed the literature on forewarning and found conflicting evidence about its potential benefit during bereavement adjustment. They identified a need for more research on how preparedness, expectations, and the suddenness of a death impact adjustment during bereavement. Although a small body of evidence suggests a link between feeling prepared and improved caregiver outcomes, few studies have investigated the factors that may help caregivers feel better prepared. Additionally, previous research may have used limited definitions of preparedness, focusing primarily on preparedness for the death, in some cases overlooking other possible interpretations of preparedness, such as feeling prepared to take on specific care-related tasks or knowing how to anticipate the trajectory of the dying process. This study asked informal caregivers to discuss how well prepared and supported they felt, with a special focus on long distance caregivers.

Method

Sample

Participants were recruited from a large Gulf Coast-based hospice organization. Potential study participants were identified within 48 hours of admission by hospice social workers using the following inclusion/exclusion criteria: (1) the patient had a primary diagnosis of cancer; and, (2) the caregivers were willing to participate in a two part survey study. Caregivers were defined as any person, other than hospice or paid staff, over 18 years of age who was functionally literate in English, that the patient (or proxy decision-maker) identified as a provider of physical, psychological, emotional, or financial assistance. In many cases multiple caregivers were identified as active participants within a patient’s care network. Each potential participant was mailed a pre-death survey with an attached consent cover letter, study brochure, and a pre-addressed, stamped envelope for return by mail. Non-responders were mailed a reminder postcard one week after the initial mailing and a duplicate survey two weeks later. Those who completed and returned the pre-death survey were sent a post-death survey three months after the patient’s death. Respondents were also given the option to complete the surveys online using a web-address printed on the survey cover. This project and its procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at Virginia Commonwealth University and Florida State University.

A total of 104 hospice patients or their proxy decision-makers were contacted, and together they identified a total of 253 informal caregivers to whom surveys were sent. In response to the mailings, 107 viable pre-death surveys and 66 post-death surveys were returned. Respectively, 53 (50 %) and 44 (67 %) of the returned surveys included responses to the qualitative prompt. Thus a total of 88 responses were included in the final analysis of qualitative data. These responses came from 69 unique individuals, 28 of whom had responded to both prompts on the pre- and post-death survey (see Table 1). The median duration between baseline and the three month follow up survey was approximately five months, 142.5 days (note: the mean duration was 174 days [SD=179] but was positively skewed due to four outliers whose length of stay exceeded 300 days).

Table 1.

Sample Descriptives based on Survey Responses to the Qualitative Prompt*

| Pre-Death Only | Post-Death Only | Both | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Respondent | 25 | 36% | 16 | 23% | 28 | 41% | 69 | 100% |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 19 | 28% | 10 | 14% | 21 | 30% | 50 | 72% |

| Male | 6 | 9% | 5 | 7% | 7 | 10% | 18 | 26% |

| Missing | -- | 0% | 1 | 1% | -- | 0% | 1 | 1% |

| Age (M/SD years)** | 54 | (15) | 58 | (13) | 61 | (14) | 58 | (14) |

| Missing | 1 | 1% | 1 | 1% | 1 | 1% | 3 | 4% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| African American | 1 | 1% | 1 | 1% | 1 | 1% | 3 | 4% |

| Native-American | 6 | 9% | -- | 0% | -- | 0% | 6 | 9% |

| Caucasian | 18 | 26% | 14 | 20% | 26 | 38% | 58 | 84% |

| Other | -- | 0% | -- | 0% | 1 | 1% | 1 | 1% |

| Missing | -- | 0% | 1 | 1% | -- | 0% | 1 | 1% |

| Relationship to Decedent | ||||||||

| The patient is my… | ||||||||

| Spouse/Partner | 8 | 12% | 5 | 7% | 9 | 13% | 22 | 32% |

| Parent | 4 | 6% | 6 | 9% | 12 | 17% | 22 | 32% |

| Sibling | 4 | 6% | 2 | 3% | 4 | 6% | 10 | 14% |

| Other | 9 | 13% | 2 | 3% | 3 | 4% | 14 | 20% |

| Missing | -- | 0% | 1 | 1% | -- | 0% | 1 | 1% |

| Caregiver Proximity | ||||||||

| Co-residing | 16 | 23% | 5 | 7% | 11 | 16% | 32 | 46% |

| Proximate | 3 | 4% | 6 | 9% | 9 | 13% | 18 | 26% |

| Long Distance | 5 | 7% | 5 | 7% | 8 | 12% | 18 | 26% |

| Missing | 1 | 1% | -- | 0% | -- | 0% | 1 | 1% |

| Decedent† | 25 | 46% | 14 | 26% | 24 | 44% | 54 | 100% |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 9 | 17% | 5 | 9% | 13 | 24% | 24 | 44% |

| Male | 16 | 30% | 9 | 17% | 11 | 20% | 30 | 56% |

| Location at Admission | ||||||||

| Home | 25 | 46% | 13 | 24% | 19 | 35% | 49 | 91% |

| Nursing Facility | -- | 0% | -- | 0% | 1 | 2% | 1 | 2% |

| Palliative Care Unit | -- | 0% | 1 | 2% | 4 | 7% | 4 | 7% |

| Length of Stay (M/SD days)** | 93 | (105) | 93 | (100) | 79 | (77) | 84 | (89) |

| Length of Stay (Median days)** | 44 | 64.5 | 48.5 | 52.5 | ||||

Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding

Age and Length of Stay are continuous variables, therefore means and standard deviations are reported.

Decedent’s age was not available for case-wise analysis. The mean age of decedents in the parent sample was 79(SD=13). Additionally, frequency totals for decedent variables do not correspond cumulatively with stratified subtotals because duplicate decedent cases where excluded from subtotals. This was necessary because there were multiple respondents from the same family.

Respondent Characteristics

As in many studies on caregivers, a majority of respondents in this sample were female (n = 50, 72%), Euro-American/White (n = 58, 84%), and had a high school education or better (n = 59, 92%). The mean age of respondents was 58 years old (SD =14). Regarding geographic proximity to the patient, 46% (n =32) of respondents co-resided with the care recipient, while 26% (n =18) qualified as proximate caregivers (outside the residence, but living <1 hour from the care recipient), and 26% (n =18) met our definition of long distance caregiver (living an hour or more away from the care recipient). Nearly a third of respondents (n = 22, 32%) were caring for a partner/spouse, 32% (n =22) for a parent, and 14% (n =10) for a sibling.

Analysis

The pre-death and post-death questionnaires gave respondents an opportunity to provide a brief (1 to 1½ page) narrative response. On both questionnaires, participants were prompted by the following statement: “Please use the space below to make any additional comments about how you could have been better prepared/supported during the care of your loved one.” Qualitative responses to these prompts were analyzed for thematic content using the constant-comparison method (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Raw data were unitized using open (or axial) coding. Coded excerpts with similar themes were grouped together. Themes from pre-death responses were separated from post-death responses and tagged for further comparison. Additionally, since long distance caregivers were of particular interest, comments provided by out-of-town caregivers were analyzed for similarities and differences. After the initial round of coding, clustering, and categorization, the findings were peer-reviewed by the second author. Many preliminary themes were corroborated; however, a number of new themes emerged during the process of peer oversight. These new themes were, again, compared and contrasted with the raw data by both researchers.

Results

Although the qualitative prompt directed respondents to comment on how they were “prepared” or “supported,” many also shared other aspects of their hospice-related caregiving experiences. Some of the identified themes were not directly related to preparedness and support, but were included in the results because they seemed important to the respondents. Three main themes were identified from the pre-death surveys: (1) Preparedness; (2) Sources of Support; and 3) the Experience of Caregiving. Five sources of support were identified: (1) Informational (communication, information, and education); (2) Hospice Staff and Volunteers; (3) Family, Friends, and Neighbors; (4) Resources - Specific Services and Equipment; and (5) Faith and Spirituality. The three subthemes in the Experience of Caregiving included: (1) Care as an Obligation or “Giving Back”; (2) Personal Sacrifices: Employment, Finances, Relationships, and Health; and (3) Disappointments with Health Care. An analysis of responses to the post-death survey generated similar themes with the addition of one: Reflection, Reminiscence, and Grief. Additionally, some of the long distance caregivers described their struggles to negotiate distance.

Pre-Death Themes

Preparedness

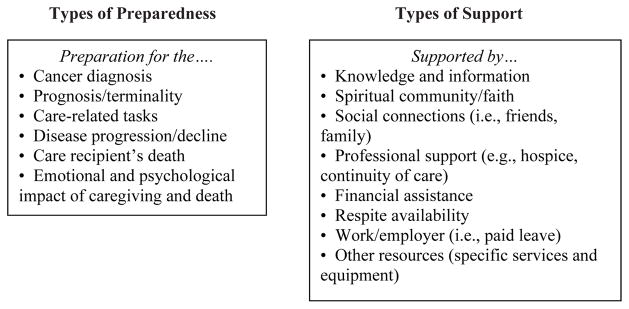

Respondents interpreted “preparedness” in a variety of different ways, such as being prepared for: specific caregiving tasks, the patient’s diagnosis/prognosis, disease progression, and death and dying (see Figure 1). Responses also included comments related to emotional adjustment, existential purpose, or “making sense of it all.” Also related to preparedness, caregivers discussed their expectations about the illness and what they anticipated their caregiving role would entail. When the expectations of respondents were closely aligned with the actual experiences, caregivers expressed feeling better prepared. For example, being provided with detailed information about the disease and dying process was frequently noted as a helpful way to prepare caregivers. Prior to the death, caregivers remarked about how unprepared they felt to confront the realities of caring for someone with cancer. Several described being caught “off guard” by the unexpected illness which made preparation a difficult, if not impossible, task:

Figure 1.

Types of Preparedness and Support Identified by Respondents

(42yo F co-residing) Prepared? There was no way for that. It hit us like wild fire.

(57yo F proximate) First, being able to accept she was terminal and if I had known how this type of cancer would affect her, it would have helped me better prepare.

Sources of Support

Figure 1 provides an overview of types of support noted by respondents. The following section illustrates these various sources of support using quotes from the caregivers.

Informational support: Communication, information, and education

Communication was a central theme identified by many respondents; being well-educated and adequately informed (e.g., about the disease process, prognosis, or caregiving role) was important. Some felt they were given the right amount of information; others described a sense of not knowing enough, or even that significant information might have been withheld from them. A subtheme associated with this topic was the importance of good communication between and among the informal caregivers and professional care providers:

(52yo F long distance) I felt uneducated, though only briefly and only because of the rush of dealing with the road of life along with the rapid deterioration of our loved one (3 months from diagnosis, about 2 weeks of hospice). Education was promptly and courteously given by hospice employees and was greatly valued.

(42yo F proximate) Unfortunately, my dad has been deemed mentally incompetent. This has resulted in a communication breakdown. It is often difficult to obtain information from Hospice regarding my dad’s status because the times I visit and the times that the Hospice staff is present often do not overlap.

Hospice staff and volunteers

In addition to being the source of much of the informational support, many respondents identified hospice personnel and services as an instrumental source of social support by their presence and guidance. The comments often included expressions of gratitude for their assistance:

(59yo F long distance) Just met the folks from Hospice last week. They were very professional and supportive of my brother and his wife and his family who are out of town. They responded very quickly to my brother’s needs and evaluated his level of pain quickly, and provided the medicines he needed for relief.

(48yo F proximate) There are no words to describe my gratitude for such a place and group of people to be in my mother’s life at this time. My mother is very happy and feels at home there.

Family, friends, and neighbors

Family members, friends, and neighbors were identified as an important source of support to caregivers. Members of this extended social network often, but not always, lived locally and frequently were connected to the patient or caregiver’s faith-based community. They offered a range of support, from assisting with activities of daily living (ADLs) (i.e., walking and transfers to and from bed), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (i.e., meal preparation and grocery shopping), or providing caregiver respite by providing food, assistance with light chores, maintaining social connections, or offering themselves as a personal confidant. In some cases non-kin, friends, and other caregivers were providing the bulk of hands-on care, while in other cases they provided auxiliary support to a primary caregiver. Close friendship motivated some non-kin caregivers to engage in caregiving. Others explained that friends were vital in the collaborative effort it takes to meet the needs of a person with advanced cancer:

(73yo F co-residing) [We] have to rely on friends and neighbors for a lot of assistance.

(59yo F co-residing) As for support, family and friends are especially wonderful.

Resources - specific services and equipment

Some respondents indicated that their resource-related needs were unmet, noting specific services, supplies, and medical equipment that could have been helpful. For example, they identified a need for help with chores and maintenance in the home, a list of private-hire caregivers in the community, a forum in which to “vent” their frustrations, and greater flexibility at work. However, while admitting a need for help, it was often difficult to ask for it:

(60yo F proximate) I need to be more willing to accept help from others. My parents were wonderful parents when I was young. I feel so much guilt that I can’t have the same energy and patience to take care of them now. Asking for help makes me feel weak.

(Demographic information not provided) What a caregiver really needs is more help in the home. Like cleaning, because you don’t have time to do it. This is so hard to keep up with.

(42yo F co-residing) I could have used more help with daily sitters. I would have liked a list (other than the phonebook) of companions. My parent does not need intensive medical care; however, a list of acceptable companions would have been helpful.

Faith and spirituality

A number of the narratives cited spiritual and religious beliefs as a strong source of personal support. The presence and availability of a faith community was frequently noted; additionally a caregiver’s belief in a higher power, sense of purpose, and prayers were described as important during their caregiving experience:

(41yo M co-residing) Faith in the Lord, inner strength, inner peace helps a lot in these times. I don’t feel I could go back on this and do anything different. You ask for the Lord’s will. Whatever his decision is you have to accept it.

(84yo F long distance) God certainly walks with us in every situation we face.

(68yo M proximate) We can never be ready for the events that come very unexpected, but as a person of deep personal faith in God, with love for our loved ones we must do what needs to be done.

(72yo F co-residing) Our pastors and church were a blessing throughout my husband’s illness.

The experience of caregiving

Care as an obligation or “giving back”

Respondents frequently mentioned that they assumed the caregiving role out of a sense of personal responsibility or obligation. In some cases, caregivers were “returning the favor” by giving care to a person who had provided care to them or others. Many described the benefits they received as a result of fulfilling these obligations. Care-related rewards (uplifts, as they are sometimes called) included cherishing the patient’s wisdom and teachings, enhanced personal strength, feeling supported by others, and enjoying the patient’s sense of humor:

(68yo M proximate) The patient involved was always a caregiver for her mother, father, and her sister, who was my mother. My brother and I are returning the love that she gave to others. She had no children of her own, she always considered my brother and I as her own children. We intended to stand by her through whatever happens.

(54yo F long distance) He went with me to another surgical procedure and fed me, gave me my medicine with the help of another friend, I am on ten medicines including 2 insulin’s. He took care of me then so I am returning the favor.

(42yo F co-residing) Because in cases like ours, I can’t work and I am the only one caring for my husband 24/7. And to me that is what I should do, it was in our vows.

(41yo M co-residing) You never know when a loved one will become deathly ill. Some try to handle it by placing them in a professional care home. Some buckle down under the stress and give in to their share of responsibility.

Personal sacrifices: Employment, finances, relationships, and health

Several caregivers noted personal sacrifices they made to ensure that the patient was adequately cared for, including some specific burdens which they experienced. Providing care was taxing on their employment, finances, personal health, and relationships. Finances, in particular, were a notable concern for some who felt increasingly economically vulnerable. This financial instability was brought on by a number of factors such as costs associated with treatment, care, and lost wages:

(62yo F proximate) I had to miss a lot of work.

(72yo F co-residing) I do wish we had been saving more and had a good insurance policy in place. I will be in serious financial problems if my husband passes away before I do.

(44yo F co-residing) It tends to cause a little of financial crippling. It has also taken time from my marriage.

Disappointments with health care

Some responses seemed to be expressions of frustration or anger, highlighting disappointing aspects of the care and services that were provided to the care recipient. The majority of criticisms were in reference to interactions with health care providers prior to the initiation of hospice services, although hospice staff members were criticized as well. Some of the perceived inadequacies had to do with staff disposition (rudeness, in particular), lack of support, disagreements regarding treatment decisions, and the lack of coordination of visits by hospice team members to the home. These criticisms were often directed toward specific team members regarding unmet needs related to desired discussion about treatment options and prognosis. Comments may provide suggestions for improving communication between providers and families providing end-of-life care:

(45yo F long distance) I wish my mom’s physician had known more about when to contact hospice.

(60yo M co-residing) The devil raised his ugly head in the form of stage four liver cancer. How could three so-called professionals be so BLIND? [referring to two oncologists and the respondent’s daughter, a registered nurse; original emphasis retained]

Post-Death Themes

Many of the themes identified during the pre-death responses were reiterated and reinforced in the post-death survey. The importance of accurate information, the support provided by hospice, and a strong sense of faith or spirituality resurfaced as potential sources of support and preparation. However, there also seemed to be a need to share and reflect about the life of the deceased person and the circumstances surrounding the dying and death process, perhaps in an attempt to try and make sense out of the experience.

Communication, information, and education

Similar to pre-death responses, bereaved individuals also commented on the importance of good communication, education, and information. Participants wanted to know more about the dying process and to get a better idea of when the death would occur:

(80yo M co-residing) I could have been better informed on what to expect as the process of dying progressed.

Preparedness

As with the caregiving role, some family members felt unprepared. However, bereaved respondents expressed feeling unprepared for how soon the death would occur, the disease process, and what it would be like during and after the death. Respondents also suggested that despite having been given accurate information in advance, they still felt a sense of uncertainty – perhaps due psychological defenses such as denial or avoidance.

(53yo M proximate) When my father died, I was actually caught off guard because I had felt that his death would be longer and more “drawn out.” But I actually think it was a blessing for him that it was not long and drawn out.

(67yo F co-residing) I was in denial as to how soon my brother would die, even though the nurse told us approximately when it would be.

Sources of support: hospice

Similar to the pre-death surveys, these respondents were also complimentary about the care and support which they received from hospice. It was apparent that many of the caregivers had developed close bonds with some hospice staff members:

(48yo F proximate) I would not have changed a thing about my mother’s care or place of care. They were wonderful to her!

(58yo F co-residing) As for the support my entire family and I got, it couldn’t have been better or any stronger. The nurses and entire staff treated my sister like a queen. She was pampered and made to feel very extra special. Of course this helped our family tremendously. I never saw a group of nurses and support personnel give 100% of their time and love to patients. Our family was just as important to them as was my sister. They hugged our necks when we came to visit and always had time to answer any questions we had.

(proximate; other demographic information not provided) Before going with [name of hospice] we met with another Hospice company. There was no comparison and our choice was easily made. Your staff [names removed] are truly special, gifted people. I’ll always cherish knowing them. They were a great support to my sister and anyone around.

Reflection, reminiscence, and grief

Bereaved participants expressed profound feelings of grief and loss. They commented on experiences of longing and a deep sense of absence. Ruminations about the decedent were also prevalent:

(72yo F co-residing) My husband fought his cancer for 11 years. We loved each other very much and just did not want our time together on earth to end. Now that he is gone, I miss him very much!

(77yo F co-residing) The actual death was so peaceful, but the void in my life is horrendous.

(58yo F co-residing) Another thing, my sister would call out to me and says [identifying content removed] please help me. That was one of the things that bothered me greatly and still haunts me today.

(63yo F co-residing) I think of my husband always with love and sometimes tears, but that’s ok. It helps to wash away the pain and I look for the laughter and love we had in our 40 years together.

Others, in their reflections upon the process, seemed to be trying to make sense of how their loved one’s death happened:

(60yo, F proximate) I really think dad waited to say goodbye. P.S. the same situation happened when we were caring for my father-in-law. As soon as his home health nurse left he passed away.

(42yo, F proximate) I believe that the combination of medicines given to my loved one hastened his death by paralyzing his lungs. (Good or bad??) who knows...as he was in constant pain.

Faith and spirituality

Reliance on spiritual beliefs, personal faith, and the availability of a religious community were noted as helpful by bereaved respondents, several of whom shared that their faith cultivated a sense of purpose, helping to make meaning out of the death. Others described their beliefs as an instrumental source of strength that contributed to a sense of continuation (e.g., to eventually be reunited with their loved one in heaven):

(60yo M co-residing) In retrospect, I fully understand that God was in control of everything concerning the end of my wife’s life here on earth.

(proximate; other demographic information not provided) The moment my sister passed away, I felt God’s presence. He lifted a burden off of me immediately and I felt he was telling me “good job.” I’ll take care of her now. The peace that overcame me was overwhelming. I was prepared for a long drawn out hard death, but God took her quickly, painless, and with dignity.

(63yo F co-residing) I know he [the decedent] is at God’s house and is waiting for me. I will join him as we will be with God forever. This is what keeps me going.

Long Distance Caregivers

In addition to some of these same themes mentioned by others, long distance caregivers often described distance as a barrier to their participation in caregiving. They wrote about their worries related to having to rely on local caregivers, questions about the quality of care, and frustrations about “not knowing”:

(52yo F long distance) My biggest concern was being 8 hours away and not knowing should I go home to visit or wait until I get the phone call. I went home for 4 days every two weeks but still worried about not being there in my dad’s house when I had to return to my home.

(49yo F long distance) The most difficult thing for me was distance. I was on one side of the U.S. and my father on the other. I was able to be with him and help with his care. I felt we both gleamed [sic] closure at the end.

In summary, results from the analysis of open-ended responses revealed a variety of topics and highlighted the uniqueness and complexity involved in caring for someone at the end of life. In general, people wanted more information, but at times were hesitant to ask. In many cases, even when caregivers where given information, they still felt unprepared for what it would be like at the end. Hospice staff were valued as a source of information, but equally important, as a source of emotional support and human connection. Many expressed profound gratitude for the care hospice provided and how they felt supported in their caregiving roles. Hospice staff provided a bridge that enabled some long distance caregivers to feel engaged in their loved one’s care, helping to negotiate the distance and deal with the emotions and obligations of providing care. The following section discusses these findings in the context of the caregiving literature and suggests how hospice social workers and other personnel might better prepare and support caregivers.

Discussion

These caregivers reinforce the importance of preparing and supporting family caregivers for both the physical and emotional aspects of this role. Hospice staff are in a position to provide the education/information to caregivers about how to access resources, provide hands-on care, and physically and emotionally prepare for the death.

Our findings are consistent with a growing body of literature that identifies effective communication among patients, family members, informal caregivers, and health care professionals as a primary means of instilling a sense of preparedness (Herbert, Schulz, Copeland & Arnold, 2009; Waldrop, Kramer, Skretny, Milch & Finn, 2005). The problem herein is that family-provider discussions on topics like potential responsiveness to treatment, disease progression, and prognosis all involve some level of uncertainty. Hospice team members can help informal caregivers feel better prepared to deal with the many unknowns, while also reassuring them that they are not expected to handle unanticipated problems alone (see Cagle & Kovacs, 2009 or Harding & Higginson, 2003 for possible strategies and considerations for dealing with the unknowns). Strategies for dealing with the unknowns can include: clarifying “what is known” and “what is knowable” (Bern-Klug et al., 2001, p. 44); presenting hypothetical scenarios and talking about what to do in a given situation; and, reminding families that disease progression and responses to care will vary from person-to-person (Cagle & Kovacs). Social workers and other health professionals are reminded that normal psychological processes such as shock and denial, as well as cultural norms and values, may complicate attempts to educate caregivers; therefore, it is important to continue to assess for when caregivers might be more receptive to additional information. The education of patients and families can avoid the appearance of “lecturing” by making the content relevant and incorporating it into the natural flow of conversation. This includes maintaining a relationship of trust and respect, an assessment of what types of information are wanted or needed, and the reiteration of key personalized information. Reassurance that it is common to not know what to say and do at this time of life may also be of comfort to some family members. Demiris and colleagues (2010) found that a structured Problem Solving Intervention (PSI) helped lower anxiety, improve problem-solving skills and helped prepare caregivers to anticipate challenges and develop a plan to address them.

Communication with health care professionals leading up to the hospice admission was also important, and at times disappointing, to family members. Some communication with physicians and staff in oncology clinics or hospitals was vague or ambiguous about hospice care or the patient’s prognosis, adding confusion about if, or when, it would be appropriate to transition to hospice care. Improved communication among differing care providers and families can enhance the continuity of care across various settings, while also reducing opportunities for medical errors and service redundancy (e.g., Lynn & Goldstein, 2003).

Social workers can anticipate and address potential areas for misinformation from outside sources (e.g., that hospice is synonymous with “giving up”) to ensure that families have an accurate understanding about the scope and limitations of hospice care. While it is important that families know what to expect from hospice providers, it is equally essential that they understand what is expected of them. For example, one respondent in our study remarked that she was unaware that she would be responsible for the bulk of the “around-the-clock care.” Social workers can also take on a leading role in efforts to educate other healthcare providers and the general public about hospice care and its mission.

Respondents desired greater support and information related to their personal finances. A number of participants remarked that their financial stability had been compromised related to the caregiving role. The exact cause of this economic instability was unclear; however, out-of-pocket expenses for treatment and care, and unpaid leave from work, were two examples provided by respondents. Previous research has also noted that a terminal diagnosis often includes a large financial “price tag,” which only further exacerbates the stressful situation (Emanuel, Fairclough, Slutsman, & Emanuel, 2000). Financial crises may worsen when families are faced with decisions regarding funeral arrangements, burial, and cremation. This is understandable given that at present, the average cost of a funeral exceeds $7,000 (National Funeral Directors Association, 2009). Concern about finances may negatively impact coping during bereavement; in fact, this has been shown to impede post-loss adjustment, particularly in women (van Baarsen & van Groenou, 2001).

Regarding the financial concerns, social workers can help families by evaluating sources of real or in-kind support within the family/caregiving network and facilitating access to external resources. Additionally, social workers can pursue macro-level changes and advocate for additional support for informal caregivers from government entities, perhaps via tax credits, expansion of the Family Medical Leave Act benefits, and/or expanding Medicaid reimbursement for caregivers. Moreover, mental health services could include more funding and support for dying persons and their families (Bern-Klug, 2004).

Respondents highlighted the vital role hospice team members play in supporting them during the provision of care. In addition to education, hands on assistance, and responsiveness during times of crisis, hospice staff were supportive by simply being present and building a trusting relationship with the patient and family. At a time when shorter lengths of service and sizeable caseloads challenge such relationship-building, it is important to note that staff presence and support is valued and considered time well-spent in support of these informal caregivers.

Although the prompt asked respondents to discuss support and preparedness “during the care of [their] loved one,” many of the bereaved respondents also described the care and support they received after the patient’s death. Bereaved respondents expressed powerful feelings of loss, sadness, and regret. We believe that, while this may not be indicative of pathology, it may provide additional evidence of the need for comprehensive bereavement support services (e.g., anticipatory grief work followed by group and individual sessions as needed) and that the emotional toll of grief should not be underestimated. Caregivers, especially those who were supported by hospice for an extended length of time, may experience the loss of provider support post-death as an additional loss. Additionally, hospice families may be less at risk for complicated grief if given more time to prepare (Barry, Kasl, & Prigerson, 2002), although our findings suggest that caregiving and post-death adjustment can be an emotionally taxing process regardless of forewarning.

Findings suggest that, in general, respondents wanted to be informed and educated with detailed information about the patient’s condition, care needs, and prognosis. They also indicated a desire to be educated about: 1) what is required of them (i.e., specific care-related tasks); 2) the extent to which care would be required; 3) what resources are available in the community, and they wanted more details about diagnosis and prognosis. However, these findings may be related to this sample of predominantly white families and may not apply to all cultural groups. It is critical to assess for the family’s needs and receptivity to information – how much, delivered to whom, by whom, when and in what format? This is fostered by a working relationship based on trust, respect, openness, and an awareness to follow the family members’ lead so they feel comfortable sharing information, raising questions, and broaching difficult subjects (Cagle & Kovacs, 2009).

Providing accurate and reliable information about services, caregiving roles, prognosis, and related end-of-life needs fosters empowerment and self-determination (Bern-Klug, 2004; Lee, 1996). Some evidence suggests that social workers may feel ill-equipped to provide education about end-of-life topics (Christ & Sormanti, 1999; Csikai & Bass, 2000; Kovacs & Bronstein, 1999). Cagle and Kovacs (2009) describe education at the end of life as a complex but critical intervention, one that can be empowering when used in a culturally relevant way. The words of these caregivers suggest implications for preparing future hospice staff and volunteers.

This study was limited in a number of ways. Due to non-probability sampling, findings may not be representative of the larger population of informal caregivers of hospice oncology patients. Indeed, the patients in our sample tended to have longer lengths of stay (nearly twice as long) when compared to the national average (NHPCO, 2009). The duration of hospice services and variations in the time between the pre-death and post-death surveys may have influenced respondent perceptions about support and preparedness. However, these data provide readers with empirically derived insight about the needs and experiences of these caregivers. Prompts were interpreted generally by respondents, and thus, findings covered a broad range of topics. Although many recurrent themes were identified, data saturation could not be verified, and the resulting themes may not be exhaustive. Future research on this topic may be strengthened by providing caregivers with more refined definitions of preparedness and support.

Implications for Social Work

With specialized knowledge about family dynamics, coping strategies, and community and other resources, hospice social workers are well positioned to help caregivers anticipate and plan for what to expect (Cagle & Kovacs, 2009). Advanced knowledge of specific care-related tasks, such as assistance with ADLS and IADLS, and having the resources, equipment, or training to successfully accomplish these tasks may help caregivers feel more prepared and less uncertain in their role. The administration of medication, for example, is one responsibility caregivers assume during the latter stages of patient’s illness. However, many caregivers express fears and concerns about following prescribed medication regimens, particularly when opioids are involved. Concerns about addiction, overdosing, or undesirable side-effects are especially common and can be disconcerting for those without medical training. Social workers can educate caregivers (and patients) and partner with other team members to help minimize uncertainty by providing accurate, evidence-based information (e.g., Cagle & Altilio, in press).

Social workers can adopt a strengths-oriented approach to help caregivers identify and articulate the many benefits of providing care, such as a sense of “giving back” or “ensuring the best possible care is being provided.” They can also support caregivers by encouraging them with positive praise, validating their efforts and sacrifices, promoting self-care activities, and viewing caregiving as a collective effort. As one respondent indicated, some caregivers may be reluctant to verbalize their needs and concerns to hospice personnel, perceiving asking for help to be a sign of weakness, ignorance, or an unnecessary burden to staff. Hospice social workers can help dispel this misconception by continually educating family members that they are expected to ask for help when needed, normalizing the experience of ‘not knowing’ and reassuring that it is the role of hospice staff to provide assistance. The PSI piloted by Demiris and colleagues (2010) may be especially be helpful to caregivers who have difficulty asking, as this intervention provides a structured process for identifying areas of concern, prioritizing and structuring a plan.

Social workers are often in the position to help the team acknowledge and connect with broader caregiving networks that may include long distance caregivers. More specifically, those who live out-of-town may be able to feel engaged through specialized roles (Roff, Martin, Jennings, Parker & Harmon, 2007) such as managing finances, offering social/emotional support by phone, and providing respite to local caregivers. In response, social workers can help involve distant caregivers through ongoing contact and proactive care planning. Social workers should also strive to include long distance caregivers in family meetings. This may be facilitated via conference calls or video phone (Demiris, Parker-Oliver, Courtney & Day, 2007; Mickus & Luz, 2002; Roff et al.; Travis et al, 2002). Fostering open communication between hospice staff and caregivers who do not live nearby may also help improve satisfaction with the care and perceptions of availability (Cagle, 2008). Increased involvement of caregivers who are distant due to location or perhaps having difficulty knowing how to connect may help minimize complicated bereavement. When inclusive family conferences are possible, social workers can discuss care-related responsibilities, current and potential needs, and available resources (Roff et al.). The caregiver may feel more empowered and involved if they help make arrangements and if service providers know to contact them with updates. This may be stressful for some, yet it may help minimize stress and facilitate involvement for others, hence, the need for a thorough, ongoing family assessment. Providing access to publications such as So Far Away: Twenty Questions for Long-Distance Caregivers (National Institute on Aging, 2007) or the Handbook for Long-Distance Caregivers (Rosenblatt & Van Steenberg, 2003) may also help distant caregivers further define and acknowledge their role.

Conclusion

Coping with the responsibilities of the caregiving role and the subsequent death of a loved one is a complex process. While some aspects of coping and loss may be universal (Center for the Advancement of Health, 2003), there is considerable variation in how people react to these life experiences. The intent of this study was to contribute to our understanding of how to better prepare and support informal caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Due to their training in family and group dynamics and cultural awareness, hospice social workers are have good foundational knowledge and skills to help facilitate the engagement of caregivers, which, according to the caregivers who shared their experiences in this study, is highly dependent upon emotional and informational support.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a doctoral fellowship through the John. A. Hartford Foundation. Dr. Cagle’s efforts were also supported, in part, by a T-32 training grant from the National Institute on Aging (NIA), 2T32AG000272-06A2 and a McGrath-Morris fellowship and residency. The authors would like to thank Maggie Clifford, MSW, and the reviewers for their help with preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Authors’ note: This research was guided by the practice experience of both authors who, in addition to conducting research on end-of-life care, have worked as hospice social workers in Florida. This experience exposed them to many family caregivers providing the care in the home, and from a distance.

Contributor Information

John G. Cagle, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Pamela J. Kovacs, Virginia Commonwealth University

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2009. 2009 Retrieved on December 24, 2009 from: http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/500809web.pdf.

- Amirkhanyan AA, Wolf DA. Caregiver stress and noncaregiver stress: Exploring the pathways of psychiatric morbidity. Gerontologist. 2003;43(6):817–827. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.6.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda S, Milne D. Guidelines for the assessment of complicated bereavement risk in family members of people receiving palliative care. Melbourne: Centre for Palliative Care; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barry LC, Kasl SV, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders among bereaved persons: the role of perceived circumstances of death and preparedness for death. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;10(4):447–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bern-Klug M. The ambiguous dying syndrome. Health & Social Work. 2004;29(1):55–65. doi: 10.1093/hsw/29.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner K, Schulz R, Horowitz A. Positive aspects of caregiving and adaptation to bereavement. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19(4):668–75. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MA, Stetz K. The labor of caregiving: A theoretical model of caregiving during potentially fatal illness. Qualitative Health Research. 1999;9(2):182–197. doi: 10.1177/104973299129121776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagle JG. VCU Digital Dissertation Archive. 2008. Informal caregivers of advanced cancer patients: The impact of geographic proximity on social support and bereavement adjustment. [Google Scholar]

- Cagle JG, Altilio T. The role of the palliative care social worker in pain and symptom management. In: Altilio T, Otis-Green S, editors. Oxford textbook on palliative social work. New York: Oxford Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cagle JG, Kovacs PJ. Education: A complex and empowering intervention at the end of life. Health & Social Work. 2009;34(1):17–27. doi: 10.1093/hsw/34.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Advancement of Health. Report on bereavement and grief research. 2003 Nov; doi: 10.1080/07481180490461188. Retrieved from: www.cfah.org/pdfs/griefreport.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading causes of death. 2009 Retrieved on December 22, 2009 from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lcod.htm.

- Christ GH, Sormanti M. Advancing social work practice in end-of-life care. Social Work in Health Care. 1999;30(2):81–99. doi: 10.1300/j010v30n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csikai EL, Bass K. Health care social workers’ view of ethical issues, practice, and policy in end-of-life care. Social Work in Health Care. 2000;32(2):1–22. doi: 10.1300/j010v32n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiris G, Parker-Oliver D, Courtney K, Day M. Use of telehospice tools for senior caregivers: A pilot study. Clinical Gerontologist. 2007;31:43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Demiris G, Parker-Oliver D, Washington K, Fruehling LT, Haggarty-Robbins D, Doorenbos A, Wechkin H, Berry D. A problem solving intervention for hospice caregivers: A pilot study. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2010;13(8):1005–1011. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, Alpert H, Baldwin D, Emanuel LL. Assistance from family members, friends, paid caregivers, and volunteers in the care of terminally ill patients. New England Journal Medicine. 1999;341(13):956–963. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909233411306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman BA, Emanuel LL. Understanding economic and other burdens of terminal illness: The experience of patients and their caregivers. Annuls of Internal Medicine. 2000;132(6):451–459. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-6-200003210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario SR, Cardillo V, Vicario F, Balzarini E, Zotti AM. Advanced cancer at home: Caregiving and bereavement. Palliative Medicine. 2004;18:129–136. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm870oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley KM, Back A, Bruera E, Coyle N, Loscalzo MJ, Shuster JL, et al., editors. When the focus is on care: Palliative care and cancer. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Given B, Wyatt G, Given CW, Sherwood P, Gift A, DeVoss D, Rahbar M. Burden and depression among caregivers of patients with cancer at the end of life. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2004;31(6):1105–1117. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.1105-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine De Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Haley WE, LaMonde AE, Han B, Narramore S, Schonwetter R. Family caregiving in hospice: Effects on psychological and health functioning among spousal caregivers of hospice patients with lung cancer or dementia. Hospice Journal. 2001;15(4):1–18. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.2000.11882959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding R, Higginson I. Working with ambivalence: Informal caregivers of patients at the end of life. Supportive Cancer Care. 2001;9(8):642–645. doi: 10.1007/s005200100286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert RS, Dang Q, Schulz R. Preparedness for the death of a loved one and mental health in bereaved caregivers of patients with dementia: findings from the REACH study. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9:683–693. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert RS, Prigerson HG, Schulz R, Arnold RM. Preparing caregivers for the death of a loved one: A theoretical framework and suggestions for future research. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9:1164–1171. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert RS, Schulz R, Copeland VC, Arnold RM. Preparing family caregivers for death and bereavement: Insights from caregivers of terminally ill patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;37(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissane D, Bloch S, Burns WI, McKenzie DP, Posterino M. Psychological morbidity in the families of patients with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1994;3:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs PJ, Bronstein L. Preparing social workers for oncology settings: What hospice social workers say they need. Health and Social Work. 1999;24(1):57–64. doi: 10.1093/hsw/24.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JAB. The empowerment approach to social work practice. In: Turner F, editor. Interlocking theoretical approaches: Social work treatment. 4. New York: Free Press; 1996. pp. 218–249. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn J, Goldstein NE. Advance care planning for fatal chronic illness: Avoiding commonplace errors and unwarranted suffering. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;138(10):812–818. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-10-200305200-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan SC. Quality of life of primary caregivers of hospice patients with cancer. Cancer Practice. 1996;4:191–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, et al. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2006;106:214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickus MA, Luz CC. Televisits: Sustaining long distance family relationships among institutionalized elders through technology. Aging & Mental Health. 2002;6(4):387–396. doi: 10.1080/1360786021000007009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Funeral Directors Association. NFDA statistics. 2009 Retrieved on March 7, 2010 from: http://www.nfda.org/about-funeral-service/trends-and-statistics.html.

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice care in America. 2009 Retrieved on December 24, 2009 from: http://www.nhpco.org/files/public/Statistics_Research/NHPCO_facts_and_figures.pdf.

- National Institute on Aging. So far away: Twenty questions for long-distance caregivers. Washington DC: Author; 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.nia.nih.gov/HealthInformation/Publications/LongDistanceCaregiving/ [Google Scholar]

- Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Sanderman R, Triemstra M, Spruijt RJ, Van Den Bos GM. Cancer and caregiving: The impact on the caregiver’s health. Psycho-Oncology. 1998;7:3–13. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199801/02)7:1<3::AID-PON320>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijboer C, Triemstra M, Tempelaar R, Mulder M, Sanderman R, van den Bos GA. Patterns of caregiver experiences among partners of cancer patients. Gerontologist. 2000;40(6):738–746. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.6.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roff LL, Martin SS, Jennings LK, Parker MW, Harmon DK. Long distance parental caregivers’ experiences with siblings: A qualitative study. Qualitative Social Work. 2007;6(3):315–334. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt B, Van Steenberg C. Handbook for long distance caregivers: An essential guide for families and friends. San Francisco, CA: Family Caregiver Alliance; 2003. Retrieved from: http://www.caregiver.org. [Google Scholar]

- Salmon JR, Kwak J, Acquaviva KD, Brandt K, Egan KA. Transformative aspects of caregiving at life’s end. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2005;29(2):121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The Caregiver Health Effects Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(23):2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2. Sage Publications; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Travis SS, Bernard M, Dixon S, McAuley WJ, Loving G, McClanahan L. Obstacles to palliation and end-of-life care in a long-term care facility. Gerontologist. 2002;42:342–349. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Baarsen B, van Groenou MI. Partner loss in later life: Gender differences in coping shortly after bereavement. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2001;6:243–262. [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop DP, Kramer BJ, Skretny JA, Milch RA, Finn W. Final transitions: Family caregiving at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8(3):623–638. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]