Abstract

Quantification of medial temporal lobe (MTL) cortices, including entorhinal cortex (ERC) and perirhinal cortex (PRC), from in vivo MRI is desirable for studying the human memory system as well as in early diagnosis and monitoring of Alzheimer’s disease. However, ERC and PRC are commonly over-segmented in T1-weighted (T1w) MRI because of the adjacent meninges that have similar intensity to gray matter in T1 contrast. This introduces errors in the quantification and could potentially confound imaging studies of ERC/PRC. In this paper, we propose to segment MTL cortices along with the adjacent meninges in T1w MRI using an established multi-atlas segmentation framework together with super-resolution technique. Experimental results comparing the proposed pipeline with existing pipelines support the notion that a large portion of meninges is segmented as gray matter by existing algorithms but not by our algorithm. Cross-validation experiments demonstrate promising segmentation accuracy. Further, agreement between the volume and thickness measures from the proposed pipeline and those from the manual segmentations increase dramatically as a result of accounting for the confound of meninges. Evaluated in the context of group discrimination between patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment and normal controls, the proposed pipeline generates more biologically plausible results and improves the statistical power in discriminating groups in absolute terms comparing to other techniques using T1w MRI. Although the performance of the proposed pipeline is inferior to that using T2-weighted MRI, which is optimized to image MTL sub-structures, the proposed pipeline could still provide important utilities in analyzing many existing large datasets that only have T1w MRI available.

1 Introduction

Developing image analysis algorithms for quantifying the volume and thickness of medial temporal lobe (MTL) cortices, including entorhinal cortex (ERC) and perirhinal cortex [PRC, further divided into Brodmann areas 35 and 36 (BA35 and BA36)], from in vivo MRI is important for studies of the human memory system as well as early diagnosis and monitoring of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Existing automatic analysis pipelines for MTL cortices are based on either whole-brain T1-weighted (T1w) MRI with ~1 mm3 isotropic resolution [1, 2] or a high-resolution T2-weighted (T2w) MRI with partial brain coverage, high in-plane resolution (~0.4 × 0.4 mm2), thick slice (~2 mm) and oblique coronal slice orientation that is optimized to image MTL sub-structures. Since the high in-plane resolution of T2w MRI better resolves boundaries of hippocampal subfields, T2w MRI has attracted more and more attention and this MRI sequence was acquired in a subset of participants in the second phase of Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Compared to T2w MRI, T1w MRI offers some advantages including: (1) Higher resolution in the anterior-posterior axis helps better resolve the folding and branching pattern of sulci; (2) It is the most commonly acquired MRI sequence and thus many large datasets are available, allowing sufficient statistical power to test various hypotheses related to AD and memory.

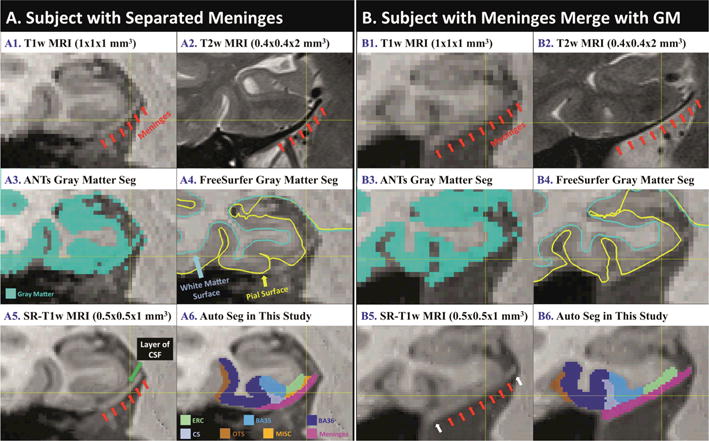

As discussed in [3], one of the reasons for gray matter (GM) over-segmentation in T1w MRI comes from the thin layer of meninges, which has similar intensity as GM in T1 contrast. The meninges consist of three layers of membranes, including dura mater, arachnoid mater and pia mater, and envelop the brain and spinal cord. Focusing on the MTL, a large proportion of the ERC and parts of the PRC appear merged with parts of the meninges in T1w MRI (Fig. 1-A1, B1). The likely mislabeling of meninges as GM by intensity-based methods would introduce errors to the quantification of ERC and PRC, potentially confounding the findings of research studies. To the best of our knowledge, none of the analysis pipelines for MTL cortices using T1w MRI have addressed this confound, and the meninges are often segmented as part of the GM by the state-of-the-art image processing algorithms (second row in Fig. 1). By contrast, in T2w MRI, meninges are easy to separate from GM due to their dark appearance in T2 contrast. Also, the higher in-plane resolution of T2w MRI reveals a thin bright layer of CSF between cortex and dura mater in many subjects (Fig. 1-A2, B2). Although this layer of CSF is usually not clearly visible in T1w MRI (Fig. 1A), in some subjects it becomes more obvious when the T1w MRI is up-sampled using the super-resolution (SR) technique [4] (denoted SR-T1w MRI, Fig. 1-A5, B5). The SR technique has been shown to be able to recover high frequency information using redundant information of neighborhood patches. In other cases, when this layer of CSF is not visible even after up-sampling (Fig. 1B), the portion of meninges near the brain stem and inferior to the collateral sulcus (CS) that is not adjacent to the GM (white arrows in Fig. 1-B5) provides clues for automatic segmentation of the meninges.

Fig. 1.

Coronal slices of T1w MRI (A1, B1) and T2w MRI (A2, B2) from the same subjects with meninges highlighted by red arrows, which are commonly segmented as gray matter by the state-of-the-art algorithms, including ANTs (A3, B3) and FreeSurfer (A4, B4). Super-resolution technique increases visibility of this structure (A5, B5) that helps automatic segmentation (A6, B6). A layer of CSF between meninges and GM is visible in SR-T1w MRI in some cases (A5) but not in all (B5).

The goal of this study is to segment ERC, PRC and the adjacent meninges in T1w MRI using a multi-atlas segmentation framework similar to that in [5]. In order to better locate the boundary between meninges and GM, we develop a T1w MRI atlas in which manual segmentations of the ERC, PRC and meninges are informed by the co-registered T2w MRI of the same subjects. Multiple experiments are performed to evaluate the performance of the proposed pipeline. First, we compare how different approaches label meninges in T1w MRI to validate that meninges are commonly labeled as GM by the state-of-the-art algorithms. Second, segmentation accuracy of the proposed pipeline relative to manual segmentations is evaluated in a cross-validation manner. Agreement between volumetric and thickness measures from different methods and those extracted from manual segmentations are compared to show the added value of accounting for the confound of meninges. Lastly, we evaluate our pipeline in the context of group difference analysis between amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI), often conceptualized as a prodromal stage of AD, and cognitive normal controls (NC). The main contributions of this paper are to bring to attention the fact that meninges can confound automatic ERC/PRC segmentation and quantification in T1w-MRI, and to demonstrate that established multi-atlas segmentation framework [5] together with SR technique [4] can reliably separate ERC/PRC from the meninges.

2 Materials

Publicly available data from [5] was used in this paper. Data consisted of 1 mm3 T1w MRI (MPRAGE) and 0.4 × 0.4 × 2 mm3 T2w MRI (TSE) from 85 subjects (41 aMCI and 44 NC). Age, sex and education are not significantly different between the two groups. The Mini-Mental State Examination of the control group (29.4 ± 0.9) is significantly higher than in aMCI (27.3 ± 1.8, p < 0.0001). Among a subset of 29 subjects (14 aMCI and 15 NC), manual segmentations of hippocampal subfields, MTL cortices (ERC, BA35, BA36), and adjacent CS are available in both hemispheres in the space of the T2w MRI. Detailed information about demographic, psychological testing results and manual segmentation protocol in T2w MRI space can be found in [5].

3 Method

We propose to segment MTL substructures, including ERC, BA35, BA36, meninges, CS and occipito-temporal sulcus (OTS), in T1w MRI by modifying an established multi-atlas segmentation framework described in [5]. Manual segmentation of the atlas set is performed in SR-T1w MRI space, guided by the manual segmentation in T2w MRI from the same subject. The proposed fully automatic pipeline only requires T1w MRI for segmentation and outputs segmentation in SR-T1w MRI space, which differs from the pipeline in [5] requiring a pair of T1w MRI and T2w MRI from the same subject as inputs. Details are described below.

3.1 Manual Segmentation of the Atlas Set

To construct an SR-T1w MRI atlas image set for multi-atlas segmentation, manual segmentations from [5] are transformed from T2w MRI space to the SR-T1w MRI for each subject, and augmented with labels for the meninges and OTS.

As discussed in Sect. 1, only subtle contrast between meninges and GM exists in SR-T1w MRI, which is not ideal for manual segmentation. On the other hand, meninges can be reliably identified in T2w MRI due to the dark appearance in T2 contrast as well as a thin layer of bright CSF separating meninges and GM (Fig. 1-A2, B2). Based on these observations and also to keep the manual segmentation in SR-T1w MRI consistent with that in T2w MRI space, we first initialize the process using the co-registered manual segmentations in T2w MRI from the same subjects and then perform manual edits according to the information in SR-T1w and T2w MRI. This includes the following steps: (1) Rigidly align T2w MRI to T1w MRI the same in [5]; (2) Up-sample T1w MRI to 0.5 × 0.5 × 1 mm3 (SR-T1w MRI) by applying SR technique [4], which is for the purpose of better visualization of meninges and sulci in T1w MRI and bringing the T1w MRI closer to the resolution of T2w MRI; (3) Resample T2w MRI and the corresponding manual segmentation to 0.4 × 0.4 × 1 mm3 using linear and nearest neighbor interpolation respectively; (4) Transform SR-T1w MRI to the up-sampled T2w MRI space. Now, the up-sampled manual segmentation in T2w MRI space serves as the initial segmentation for the registered SR-T1w MRI.

Hippocampal subfield labels in the T2w MRI manual segmentation are excluded due to MTL cortices being the regions of interest in this study. The remaining four labels, i.e. ERC, BA35, BA36 and CS, are manually corrected for errors introduced by highly anisotropic voxel size of T2w MRI, rigid inter-modality registration and the up-sampling of both modalities. The sulcus lateral to CS is segmented as OTS. Label of meninges is then assigned to the voxels inferior to the corrected MTL labels that have gray appearance in SR-T1w MRI and dark appearance in T2w MRI (the first row in Fig. 1). The thin layer of CSF between meninges and GM, which has high intensity in T2w MRI, may not be visible in SR-T1w MRI due to partial volume effect. If it is visible in some cases, i.e. a layer of voxels that have much darker intensity between meninges and GM in SR-T1w MRI (Fig. 1-A5), miscellaneous label is assigned. The anterior and posterior extents of meninges are limited to the slices where ERC and PRC are visible. As described in [5], the ERC/PRC anterior border is 2 mm anterior to the of hippocampus anterior border, and the ERC/PRC posterior border is 2 mm posterior to the uncal apex. In the end, the newly generated manual segmentation of the registered SR-T1w MRI in up-sampled T2w MRI space is resampled back to the SR-T1w MRI. As such, each atlas consists of the T1w MRI, SR-T1w MRI, and the corresponding manual segmentation in SR-T1w MRI space.

3.2 Multi-atlas Segmentation

During automatic segmentation, T1w MRI of the target subject is first up-sampled to 0.5 × 0.5 × 1 mm3 using the SR technique [4]. The regions of interest (ROI) around the left and right MTL are identified in the target SR-T1w image by registering to a whole-brain template, constructed using all the subjects in the atlas set. For each target ROI, the corresponding ROIs in the atlas set are registered to it using ANTs with normalized cross-correlation metric [6]. Atlas labels are then warped to the target ROI and combined using the joint label fusion algorithm [7]. The process is repeated in a bootstrapping fashion, where the initial segmentation of the target structures is used to initialize affine alignment between the atlas and target ROIs. This bootstrapping results in fewer failed atlas-to-target registrations and better overall segmentation accuracy. Final automatic segmentations are generated in the target SR-T1w MRI space.

4 Experiments and Results

4.1 Segmentation and Quantification

Primary validation was performed on the set of 29 subjects for whom T1w MRI, T2w MRI and manual segmentations of the SR-T1w MRI and T2w MRI are available. Using the proposed pipeline, automatic segmentations in SR-T1w MRI space were generated for these subjects in a leave-one-out manner by using the remaining 28 subjects as atlases. Additionally, the whole 29-subject atlas set was used to segment SR-T1w MRI in the remaining 56 subjects. Volume measurements (T1-Volume) were derived directly from the automatic segmentations. A multi-template thickness analysis pipeline, which is optimized for the analysis of MTL cortices [8], was applied to the automatic segmentations to extract summary thickness measures (T1-Thickness). Automatic segmentations in T2w MRI space were also generated using the pipeline in [5]. Volume (T2-Volume) and summary thickness measurements (T2-Thickness) were extracted the same way as above for comparisons. In order to demonstrate the added value of accounting for the confound of meninges, we compared the proposed pipeline to two state-of-the-art T1w MRI analysis algorithms. First, FreeSurfer 6.0 [1] was applied to T1w MRI to compute volume (FS-Volume) and thickness (FS-Thickness) of ERC and PRC (closed to BA35 in our protocol). Second, an established method implemented in the ANTs package [2] was used to extract a cortical thickness map, and this map was integrated over the ERC, BA35 and BA36 (resampled into T1w MRI space) to generate summary thickness measurements (ANTs-Thickness).

4.2 Evaluations

Firstly, we investigate the extent to which the established analysis methods for T1w MRI [1, 2] mislabel meninges. We compute the average percentage of voxels labeled as meninges in the manual segmentations that are mislabeled as GM or CSF. Manual segmentations and automatic segmentations generated by the proposed pipeline in SR-T1w MRI are first resampled to T1w MRI space. The results, shown Table 1, support the notion that large proportion of meninges is segmented as GM by the state-of-the-art algorithms (ANTs: 92.6 %; FreeSurfer: 71.0 %). We note that these methods do not have a specific label for meninges, and have to label the meninges voxels as something; including them in the GM introduces error to cortical thickness computations. On the other hand, the majority (75.2 %) of meninges voxels are correctly labeled by the proposed pipeline and only 6.5 % of them are labeled as GM.

Table 1.

Comparisons of different analysis methods in labeling meninges.

In addition, average Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) of the automatic segmentations relative to the corresponding manual segmentations among the atlas set in SR-T1w MRI and T2w MRI are reported in Table 2. The accuracy of the proposed pipeline is not as high as that in T2w MRI, and could due to the poorer ability to resolve GM boundaries limited by low resolution and the confound of meninges in T1w MRI. On the other hand, the high accuracy in segmenting meninges indicates that the layer of CSF between meninges and GM as well as the portions of meninges that are not merged with GM provide important features for reliable segmentation of meninges.

Table 2.

Average DSC between automatic and manual segmentations of the proposed pipeline and [5], measured by leave-one-out cross validation among the atlas set.

| Modality | Cortical labels | Sulci labels | Meninges | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERC | BA35 | BA36 | CS | OTS | ||

| SR-T1w MRI | 0.715 ± 0.077 | 0.671 ± 0.092 | 0.755 ± 0.063 | 0.552 ± 0.168 | 0.566 ±0.189 | 0.723 ± 0.075 |

| T2w MRI [5] | 0.789 ± 0.048 | 0.710 ± 0.072 | 0.789 ± 0.056 | 0.675 ± 0.093 | 0.635 ± 0.017 | N/Aa |

Meninges is not part of the segmentation protocol for T2w MRI.

Further, we compute intra-class correlation (ICC) between volume and thickness measurements extracted from the segmentations in the atlas set using various automatic approaches and those obtained using manual segmentations in T2w-MRI space (which we consider to be the most reliable measures of volume and thickness due to higher resolution and better GM/meninges contrast in T2w MRI). Thickness is computed from the manual segmentations at T2w MRI by (1) generating a mesh for the union of ERC, BA35 and BA36 labels, (2) extracting the pruned Voronoi skeleton [9] of the mesh, (3) measuring the distance between each surface vertex and the closest point on the skeleton and (4) integrating thickness values for all the vertices on the surface mesh belong to each label. The results, shown in Table 3, indicate excellent agreement for automatic T1 measures and T2 measures of ERC and BA35 and acceptable agreement at BA36. Bias is high for ANTs-Thickness and FS measures, which is the result of not accounting for the confound of meninges in the analysis.

Table 3.

ICC between measures extracted from automated techniques and those from manual segmentations in T2w MRI space.

| Thickness Measures | ERC | BA35 | BA36 | Volume Measures | ERC | BA35 | BA36 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1-Thicknessa | 0.820 | 0.873 | 0.494 | T1-Volumea | 0.796 | 0.815 | 0.801 |

| T2-Thicknessa | 0.824 | 0.829 | 0.623 | T2-Volumea | 0.836 | 0.830 | 0.838 |

| ANTs-Thickness | 0.301 | 0.503 | 0.428 | ||||

| FS-Thicknessb | 0.475 | 0.570 | N/A | FS-Volumeb | 0.689 | 0.478 | N/A |

extracted from automatic segmentation in leave-one-out setting;

segmentation protocol is different.

To evaluate the clinical utility of the proposed pipeline, Analysis of Covariance, with age and intracranial volume (ICV, computed the same way as in [5]) as covariates, is performed on the full dataset (n = 85) for all the summary measurements to investigate their statistical power in discriminating aMCI from NC. We also perform ROC analysis to these measurements after residualizing by age and ICV, and report area under the curve (AUC) for group discrimination. The largest effect, in absolute terms, is found in the thickness of the left BA35 extracted using the T2-based segmentation pipeline (t = 4.42, p = 3.1e−5, AUC = 0.756). A similar effect is also detected by the T1-based pipeline in the left BA35 thickness (t = 4.04, p = 1.2e−4, AUC = 0.743). Left ERC thickness is the FreeSurfer measurement with the largest t-statistic and AUC value (t = 3.53, p = 6.9e−4, AUC = 0.708). Since ERC is defined more laterally in FreeSurfer comparing to our protocol, this measure may pick up the same effect as the former two BA35 measurements. ANTs-Thickness gives the best result in left BA36 (t = 4.05, p = 1.2e−4, AUC = 0.742). However, better group discrimination in BA35 rather than in BA36 is more biologically plausible given the earlier involvement of BA35 in AD [10]. The rank of discriminative power of various techniques, i.e. left BA35 T2-Thickness > left BA35 T1-Thickness > the other two T1 measures, is in the expected direction considering GM segmentation reliability at this region. However, the differences are only in absolute terms and evaluation in a larger study, such as ADNI, would be necessary to further compare these techniques statistically.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we proposed to segment MTL cortices as well as meninges in T1w MRI using an established multi-atlas segmentation framework [5] together with SR technique [4]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that explicitly accounts for the confound of meninges in the quantification of MTL cortices using T1w MRI. Experimental results demonstrate that unlike widely used brain MRI segmentation techniques, the proposed pipeline seldom labels meninges as GM, and generates summary thickness and volume measurements that are more consistent with those extracted from manual segmentations. The proposed pipeline is not as reliable or accurate as T2w-based segmentation of ERC and PRC, suggesting that the T2w MRI should be preferred for studies focused on these structures. However, T1w MRI is much more common in today’s neuroimaging studies, and the proposed approach makes it possible to generate ERC and PRC measures that are strongly consistent with T2w-measures. Thus we expect it to have significant application in the analysis of retrospective and prospective brain imaging data, particularly in studies involving AD, aging and memory. Future work will include making the manual segmentations with meninges available to the community, evaluation in a larger dataset, improving segmentation accuracy and extending the pipeline to other regions of the brain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH (grant numbers R01-AG040271, P30-AG010124, R01-AG037376, R01-EB017255).

References

- 1.Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage. 2012;62:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das SR, Avants BB, Grossman M, Gee JC. Registration based cortical thickness measurement. Neuroimage. 2009;45:867–879. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutton C, De Vita E, Ashburner J, Deichmann R, Turner R. Voxel-based cortical thickness measurements in MRI. Neuroimage. 2008;40:1701–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manjón JV, Coupé P, Buades A, Fonov V, Collins DL, Robles M. Non-local MRI upsampling. Med Image Anal. 2010;14:784–792. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yushkevich PA, Pluta JB, Wang H, Xie L, Ding S, Gertje EC, Mancuso L, Kliot D, Das SR, Wolk DA. Automated volumetry and regional thickness analysis of hippocampal subfields and medial temporal cortical structures in mild cognitive impairment. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:258–287. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avants BB, Epstein CL, Grossman M, Gee JC. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med Image Anal. 2008;12:26–41. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Suh JW, Das SR, Pluta J, Craige C, Yushkevich PA. Multi-atlas segmentation with joint label fusion. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2012;35:611–623. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2012.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie L, et al. Automatic clustering and thickness measurement of anatomical variants of the human perirhinal cortex. In: Golland P, Hata N, Barillot C, Hornegger J, Howe R, editors. MICCAI 2014, Part III LNCS. Vol. 8675. Springer; Heidelberg: 2014. pp. 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogniewicz RL, Kübler O. Hierarchic voronoi skeletons. Pattern Recognit. 1995;28:343–359. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braak H, Braak E. Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]