Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study is to report short and long term outcomes following congenital heart defect (CHD) interventions in patients with Trisomy 13 or 18.

Methods

A retrospective review of the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium (PCCC) identified children with Trisomy 13 or 18 with interventions for CHD between 1982 and 2008. Long term survival and cause of death was obtained through linkage with the National Death Index.

Results

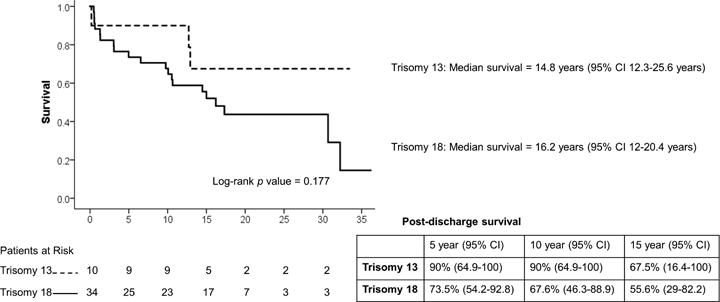

A total of 50 patients with Trisomy 13 and 121 with Trisomy 18 were enrolled in PCCC between 1982 and 2008; among them 29 patients with Trisomy 13 and 69 patients with Trisomy 18 underwent intervention for CHD. In-hospital mortality for patients with Trisomy 13 or Trisomy 18 was 27.6% and 13%, respectively. Causes of in-hospital mortality were primarily cardiac (64.7%) or multiple organ system failure (17.6%). National Death Index linkage confirmed 23 post-discharge deaths. Median survival (conditioned to hospital discharge) was 14.8 years (95% CI 12.3–25.6 years) for patients with Trisomy 13 and 16.2 years (95% CI 12–20.4 years) for patients with Trisomy 18. Causes of late death included cardiac (43.5%), respiratory (26.1%), and pulmonary hypertension (13%).

Conclusions

In-hospital mortality for all surgical risk categories was higher in patients with Trisomy 13 or 18 than reported for the general population. However, patients with Trisomy 13 or 18, who were selected as acceptable candidates for cardiac intervention and who survived CHD intervention, demonstrated longer survival than previously reported. These findings can be used to counsel families and make program-level decisions on offering intervention to carefully selected patients.

Classifications: Congenital heart disease, database, genetic syndromes, outcomes

Trisomy 13 (T13) and 18 (T18) are frequently (up to 80%) associated with multiple anomalies including congenital heart defects (CHD) such as atrial or ventricular septal defects (ASD, VSD), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD), tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) and others [1]. These lesions can be successfully repaired or palliated in the general population; a previous study from the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium (PCCC) reported 91% hospital discharge survival in patients with T13 or T18 [2]. Historically, the presence of T13 or T18 has been considered to be incompatible with long term survival, with death occurring frequently within one year and mostly attributed to causes other than the associated CHD [3–5]. A recent large study of children with Trisomy 13 or 18 reported a 5-year survival of 9.7% for children with T13 and 12.3% for children with T18, although clinical treatment data were not available [6]. Because of this short expected lifespan, and the low functional status of these patients, aggressive treatment of associated CHD has been controversial.

Studies published in the past decade suggest that survival in children with T13 and T18 may be longer after intervention for CHD [7–10]. A Japanese study of 34 patients with T18 reported 22% two-year survival following corrective or palliative cardiac surgery, compared to 9% survival with only medical therapy [7]. Similarly, improved survival with surgical management has been reported by other small studies [8, 9]. However, these small series with relatively short postoperative follow up are not sufficient to guide healthcare providers and families regarding long term survival after CHD interventions in patients with T13 or T18. At the same time, there is increased need for this information as families have become increasingly knowledgeable through social media, support groups, and the internet, and are considering interventions for their children [11].

We report long term survival and causes of death in a subgroup of patients with T13 and T18 from the PCCC cohort with long term follow up data available through linkage with the National Death Index (NDI).

Patients and Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota, Emory University, and Memorial Care Health Services, with a waiver of consent and HIPAA Authorization. A Data Use Agreement was in place between the investigators and respective institutions.

Data Collection

The PCCC was established in 1982 as a multicenter registry for the purpose of quality improvement [12]. Between 1982 and 2008, the PCCC collected data on over 137,000 patients, 118,000 operations, and 123,000 cardiac catheterizations [13]. This retrospective review included patients from the US and Canada who were enrolled in the PCCC from 1982 to 2008 with a diagnosis code for T13 or T18 (including mosaic forms) and CHD. Short term mortality was defined as in-hospital death following CHD intervention. Patients were assigned to one of three treatment pathways; 1) corrective, which included complete CHD repair, with or without initial palliation; 2) palliative, which included PDA ligation with co-existing significant intracardiac CHD, pulmonary artery banding, or aorto-pulmonary shunt; and 3) single ventricle palliation, which included bi-directional Glenn anastomosis or Fontan procedure. Treatment era was separated into three groups; 1982–1989, 1990–1999, and 2000–2008. Age groups were defined as neonates (< 30 days), infants (31 days to 1 year), and children (> 1 year and < 18 years). Primary surgical procedure was defined as the first surgical procedure that addressed the main anatomic abnormality of each patient. Surgical procedure complexity was scored using the Society of Thoracic Surgeons-European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery Congenital Heart Surgery Mortality (STAT) risk categories [14]. For patients with multiple procedures in the same admission, the primary procedure was considered the one with highest STAT risk score. For comparison purposes with same-era procedures from within the PCCC, we also assigned Risk Adjustment in Congenital Heart Surgery, version 1 (RACHS-1) complexity categories [15,16]. Procedural indications were abstracted as reported in the catheterization and operative notes. Complications included those reported by the participating centers or identified by registry staff during the coding process.

Long term mortality was defined as post-hospital discharge mortality and was available for the US sub-cohort with sufficient direct identifiers, enrolled in PCCC prior to April 15, 2003 (date that stricter Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act [HIPAA] privacy rule took effect). This subgroup was submitted to the National Death Index (NDI) to obtain survival status and cause of death up to December 31, 2014 [17]. NDI information is considered to be the gold standard of national death registries for obtaining mortality data in the US [18]; the sensitivity of the PCCC-NDI linkage reaches 88.1% (95% CI, 87.1–89.0) with a specificity exceeding 99%, when a patient’s first and last name is available [17].

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study cohort by genetic diagnosis. Comparisons between groups were analyzed using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank tests were used to describe long term survival and compare groups, respectively, in the subset of patients who were submitted to the NDI with first and last name available. Follow up duration was determined from the date of first cardiac intervention. Statistical analysis was completed using Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) (IBM, Armonk, NY) version 23.

Results

Fifty patients with T13 and 121 with T18 were identified, including mosaic or partial trisomy cases (20 for T13 and 16 for T18). Seventy-three patients (21 T13, 52 T18) were excluded from further analysis because they did not undergo CHD intervention. Characteristics of patients with and without interventions are described in Table 1. Compared to patients offered intervention, patients not offered intervention were more likely to be born in an earlier decade, have lower birth weight, have increased incidence of co-morbidities and single ventricle cardiac defect, and patients with T13 had a higher incidence of pulmonary atresia. A flow chart of patient selection and exclusion is shown in Supplemental Figure 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of Patients with and without Cardiac Interventions

| Trisomy 13 (N = 50) | Trisomy 18 (N = 121) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variable | With intervention | Without intervention | P valuea | With Intervention | Without intervention | P valuea |

| Total N (%) | 29 (58) | 21 (42) | 69 (57) | 52 (43) | ||

| Male N (%) | 14 (48.3) | 15 (71.4) | 0.148 | 21 (30.4) | 23 (44.2) | 0.131 |

| Birth Era N (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Prior to 1980 | 0 | 5 (23.8) | 3 (4.3) | 11 (21.1) | ||

| 1980–1989 | 3 (10.3) | 7 (33.3) | 8 (11.6) | 17 (32.7) | ||

| 1990–1999 | 9 (31.0) | 9 (42.9) | 24 (34.8) | 24 (46.2) | ||

| 2000–2009 | 17 (58.7) | 0 | 34 (49.3) | 0 | ||

| Birth Weight (kg) | 3.0 | 2.3 | 0.007 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 0.001 |

| Median (IQR) | (2.3–3.5) | (1.8–2.7) | (2.1–2.6) | (1.4–2.2) | ||

| Mosaic/partial | 18 (62.7) | 2 (9.5) | 0.001 | 10 (14.5) | 6 (11.5) | 0.788 |

| Trisomy Comorbidities | ||||||

| Prematurity | 1 (3.4) | 11 (52.4) | <0.001 | 11 (15.9) | 18 (34.6) | 0.02 |

| Preop gastrostomy | 4 (13.8) | 0 | N/A | 5 (7.2) | 5 (9.6) | 0.743 |

| Preop tracheostomy | 2 (6.9) | 0 | N/A | 1 (1.4) | 2 (3.8) | 0.576 |

| Preop ventilator | 4 (13.8) | 8 (38.1) | 0.091 | 9 (13) | 19 (36.5) | 0.004 |

| Major GI abnormality | 4 (13.8) | 5 (23.8) | 0.464 | 6 (8.7) | 12 (23.1) | 0.038 |

| Cleft lip/palate | 5 (17.2) | 10 (47.6) | 0.03 | 4 (5.8) | 4 (7.7) | 0.724 |

| Renal abnormality | 3 (10.3) | 6 (28.6) | 0.14 | 2 (2.9) | 10 (19.2) | 0.004 |

| Primary Diagnosis | 0.009 | 0.112 | ||||

| VSD/DORV-VSD | 7 (24.1) | 2 (9.5) | 32 (46.4) | 26 (50) | ||

| TOF/DORV-TOF | 8 (27.5) | 6 (28.6) | 12 (17.4) | 6 (11.5) | ||

| CoA/IAA | 8 (27.5) | 1 (4.8) | 7 (10.1) | 4 (7.7) | ||

| AVSD | 1 (3.5) | 0 | 6 (8.7) | 5 (9.6) | ||

| Pulmonary atresia | 1 (3.5) | 6 (28.6) | 3 (4.4) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| Single ventricle | 0 | 5 (23.7) | 2 (2.9) | 9 (17.3) | ||

| PDA | 1 (3.5) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (8.7) | 0 | ||

| DORV-TGA type | 1 (3.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.9) | ||

| ASD | 2 (6.9) | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 0 | ||

| Dx Cardiac Cath | 11 (37.9) | 5 (23.7) | 0.365 | 39 (56.5) | 19 (36.5) | 0.043 |

| In - hospital mortality | 8 (27.6) | 19 (90.5) | N/A | 9 (13) | 36 (69.2) | N/A |

| In - hospital mortality | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Mosaic/partial | 1/18 (5.6) | 0/10 (0) | ||||

| Not mosaic/partial | 6/11 (54.5) | 7/59 (11.9) | ||||

|

Postop LOS (days) median (IQR) |

10.5 (6–28) |

N/A | N/A | 12 (7–22.8) |

N/A | N/A |

|

Hospital LOS median (IQR) |

15 (4–38) |

2 (1–5) |

N/A | 14 (2.5–26.5) |

2 (1–5.8) | N/A |

| Treatment Pathway | ||||||

| Palliative | 8 (27.6) | N/A | N/A | 19 (27.5) | N/A | N/A |

| Corrective | 21 (72.4) | N/A | N/A | 48 (69.6) | N/A | N/A |

| Single ventricle | 0 | N/A | N/A | 2 (2.9) | N/A | N/A |

P value for Chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Given are frequency (N) and % for categorical variables, median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. GI = gastrointestinal; Dx = diagnostic. N/A = statistical comparison not performed.

In-Hospital Outcomes

Characteristics of 29 intent-to-treat patients with T13 and 69 with T18 are described in Table 1. The most common CHD was VSD in 38/98 (38.8%), followed by TOF or pulmonary valve stenosis in 20/98 (20.4%). Most patients received single stage corrective surgery or transcatheter intervention (n=61, 62.2%), with 8 patients (8.2%) undergoing initial palliation prior to definitive surgical intervention. The remainder (n = 27, 27.5%) received palliative interventions only, and 2 patients received single ventricle palliation. Preoperative co-morbidities were relatively common, including tracheostomy, gastrostomy, and other major congenital anomalies. In-hospital mortality for intent-to-treat patients identified as having a mosaic or partial trisomy was lower than those not reported as having mosaic or partial forms of trisomy, particularly for T13 (see Table 1).

There were 95 surgical procedures performed in 87 patients (see Table 2). The most common surgical indication was heart failure in 36.8%, but 10.5% of patients were prostaglandin dependent and 12.6% were ventilator dependent. Overall procedural complexity included 66.3% in STAT categories 1 and 2, 33.7% in STAT categories 3 and 4, and no operations in STAT category 5.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Surgical Procedures

| Variable | Trisomy 13 (N= 30) | Trisomy 18 (N = 65) | Overall (N= 95) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N (%)a | Median (IQR)a | N (%)a | Median (IQR)a | N (%)a | Median (IQR)a | |

| Age at Surgery (months) | 3.2 (0.6–8.6) |

6.2 (1.4–16.7) |

4.6 (1–15.7) |

|||

| Weight at Surgery (kg) | 3.8 (3.2–7.3) |

4.3 (2.7–6.4) |

4.2 (2.9–6.6) |

|||

| Primary Surgical Indication | ||||||

| Prostaglandin dependent | 6 (20) | 4 (6.2) | 10 (10.5) | |||

| Ventilator dependent | 3 (10) | 9 (13.8) | 12 (12.6) | |||

| Cyanosis | 8 (26.7) | 10 (15.4) | 18 (18.9) | |||

| Heart failure/FTT | 6 (20) | 29 (44.6) | 35 (36.8) | |||

| Significant shunt | 2 (6.7) | 4 (6.2) | 6 (6.3) | |||

| Significant obstruction | 3 (10) | 2 (3.0) | 5 (5.2) | |||

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1 (3.3) | 7 (10.8) | 8 (8.4) | |||

| Other | 1 (3.3) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | |||

| Primary Surgical Procedure | ||||||

| ASD closure | 2 (6.7) | 1 (1.5) | 3 (3.2) | |||

| VSD closure | 6 (20) | 27 (41.6) | 33 (34.8) | |||

| TOF repair | 6 (20) | 6 (9.2) | 12 (12.6) | |||

| CoA repair (thoracotomy) | 4 (13.3) | 6 (9.2) | 10 (10.5) | |||

| CoA/IAA repair (sternotomy) | 4 (13.3) | 1 (1.5) | 5 (5.3) | |||

| PDA ligation | 2 (6.7) | 5 (7.7) | 7 (7.4) | |||

| Pulmonary artery band | 2 (6.7) | 7 (10.8) | 9 (9.5) | |||

| Aortopulmonary shunt | 4 (13.3) | 6 (9.2) | 10 (10.5) | |||

| Bi-directional Glenn or | 2 (3.1) | |||||

| Fontan | 0 | 2 (2.1) | ||||

| Pulmonary valvotomy | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1) | |||

| AVSD repair | 0 | 2 (3.1) | 2 (2.1) | |||

| DORV repair | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1) | |||

| Primary Procedure STAT | ||||||

| 1 | 10 (33.3) | 33 (50.7) | 43 (45.3) | |||

| 2 | 8 (26.7) | 12 (18.5) | 20 (21) | |||

| 3 | 5 (16.7) | 4 (6.2) | 9 (9.5) | |||

| 4 | 7 (23.3) | 16 (24.6) | 23 (24.2) | |||

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Primary procedure RACHS-1 | ||||||

| 1 | 5 (16.7) | 7 (10.8) | 12 (12.6) | |||

| 2 | 12 (40) | 34 (52.3) | 46 (48.5) | |||

| 3 | 10 (33.3) | 23 (35.4) | 33 (34.7) | |||

| 4 | 3 (10) | 1 (1.6) | 4 (4.2) | |||

| 5 or 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Unable to assign | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Postoperative Complications | ||||||

| Postop new pacemaker | 0 | 6 (9.2) | 6 (6.3) | |||

| Postop ECLS | 3 (10) | 0 | 3 (3.2) | |||

| Delayed Sternal Closure | 4 (13.3) | 5 (7.7) | 9 (9.5) | |||

| Unplanned Postoperative Non - Cardiac Operations | ||||||

| Tracheostomy | 2 (6.9) | 3 (4.6) | 5 (5.3) | |||

| Gastrostomy | 1 (3.4) | 7 (10.8) | 8 (8.4) | |||

Given are frequency (N) and percent (%) for categorical variables, median and IQR for continuous variables. FTT = failure to thrive; ECLS = extracorporeal life support.

Surgical morbidity included need for extracorporeal life support in 3 patients with T13 (10%), need for permanent pacemaker in 6 patients with T18 (9.2%), and delayed sternal closure in 9 patients (9.5%). Surgical procedures associated with need for permanent pacemaker included VSD closure (n = 4), TOF repair (n = 1) and ASD closure (n = 1). Median postoperative LOS was 10.5 days (IQR 6–28 days) for patients with T13 and 12 days (IQR 7–22.8 days) for patients with T18. In-hospital mortality was 27.6% (8/29) for patients with T13 and 13% (9/69) for patients with T18.

Fifty patients underwent 71 cardiac catheterization procedures (see Table 3). The most common interventional procedure was pulmonary artery angioplasty.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Cardiac Catheterization Procedures

| Trisomy 13 (N= 17) | Trisomy 18 (N = 54) | Overall (N= 71) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Variable | N (%)a | Median (IQR)a | N (%)a | Median (IQR)a | N (%)a | Median (IQR)a |

| Age at Catheterization (months) | 18.4 (4 – 37.6) |

13.1 (5.2–38.3) |

14.4 (5 – 36.8) |

|||

| Weight at Catheterization (kg) | 9.2 (5.6–13.3) |

6.1 (3.9–10.9) |

6.7 (4–11.3) | |||

| Indication for Catheterization | ||||||

| Heart failure/FTT | 3 (17.6) | 10 (18.5) | 13 (18.3) | |||

| Significant pressure gradient | 5 (29.5) | 7 (13) | 12 (16.9) | |||

| Significant shunt | 1 (5.9) | 4 (7.4) | 5 (7.0) | |||

| Pulmonary hypertension | 3 (17.6) | 2 (3.7) | 5 (7.0) | |||

| Cyanosis/hypercyanotic spells | 3 (17.6) | 13 (24.1) | 16 (22.6) | |||

| Preoperative planning | 2 (11.8) | 17 (31.5) | 19 (26.8) | |||

| Missing data | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.4) | |||

| Procedure Type | ||||||

| Diagnostic | 15 (88.2) | 40 (74.1) | 55 (77.5) | |||

| Interventional | 2 (11.8) | 14 (25.9) | 16 (22.5) | |||

| PDA closure (% of interventional) | 0 | 2 (14.3) | 2 (12.5) | |||

| Aortic valvuloplasty | 1 (50) | 0 | 1 (6.3) | |||

| CoA angioplasty | 1 (50) | 2 (14.3) | 3 (18.7) | |||

| Pulmonary artery angioplasty | 0 | 7 (50) | 7 (43.7) | |||

| PA/RVOT stent | 0 | 2 (14.3) | 2 (12.5) | |||

| Angioplasty Fontan circuit | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) | |||

Given are frequency (N) and percent (%) for categorical variables, median and IQR for continuous variables. FTT = failure to thrive.

Long Term Survival

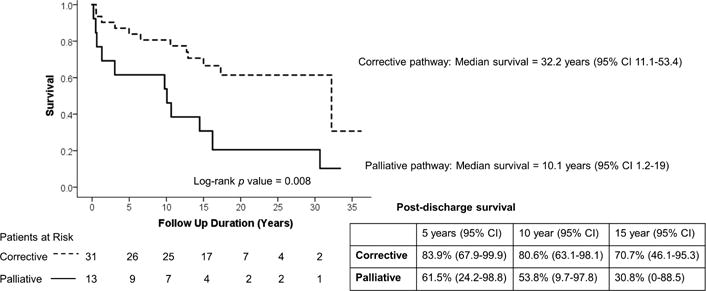

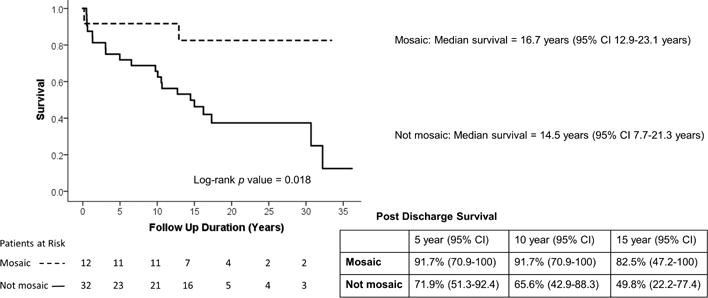

Of the 81 hospital survivors, 56 were enrolled in the pre-HIPPA era and were eligible for NDI linkage. From the eligible patients, 44 [10 T13 and 34 T18] patients had sufficient direct identifiers for reliable linkage with the NDI. There were no significant differences between the group with sufficient identifiers and the group without sufficient identifiers (see Supplemental Table 1). NDI linkage confirmed 23 post-hospital discharge deaths, including one death within 30 days of discharge. Conditioned survival post discharge following CHD intervention in patients with T13 or T18 is shown in Figure 1. There was no statistical difference in the median survival of T13 (14.8 years; 95% CI 12.3–25.6 years) vs T18 patients (16.2 years; 95% CI 12–20.4 years). There were no significant differences in survival by gender (results not shown). Figure 2 shows Kaplan-Meier survival plot by treatment pathway, conditioned on surviving intervention for CHD. Patients on a corrective treatment pathway demonstrated median survival of 32.2 years (95% CI 11.1–53.4 years), while patients on a palliative treatment pathway demonstrated shorter median survival of 10.1 years (95% CI 1.2–19 years) (p =0.008). Figure 3 shows that patients who were identified as having a mosaic or partial form of Trisomy 13 or 18 demonstrated longer median survival (16.7 years, 95% CI 12.9–23.1 years) than patients not reported as mosaic or partial Trisomy 13 or 18 (14.5 years, 95% CI 7.7–21.3 years) (p = 0.018).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier conditioned survival following intervention for CHD in Trisomy 13 and 18 patients.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier conditioned survival following intervention for CHD in Trisomy 13 and 18 patients by treatment pathway.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier conditioned survival following intervention for congenital heart disease in mosaic and not mosaic Trisomy 13 and 18 patients.

Causes of In-Hospital and Long Term Death

Table 4 describes primary causes of death, for both in-hospital and post-discharge deaths identified through NDI linkage. The most common primary causes of in-hospital death were cardiac failure (64.7%) and multiple organ system failure (17.6%). Pulmonary hypertension in Trisomy 13 and 18 patients with left-to-right shunt lesions may occur early in life in more than 50% of these patients and this can complicate the course of CHD before and after interventional management [9]. Figure 4 illustrates mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) in a subset of 14 T13/T18 patients with VSD who underwent cardiac catheterization prior to VSD closure. Patients who died in-hospital following VSD closure were younger, and had higher mean PAP and PVR than those patients who survived to hospital discharge, but the sample size is relatively small to draw definitive conclusions. Causes of post-discharge death identified through NDI linkage were primarily cardiac, followed by respiratory diseases and pulmonary hypertension.

Table 4.

Primary Causes of In-hospital and Post-Discharge Death

| Cause | In-Hospital Death N= 17 (%) |

Post-Discharge Death N= 23 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac failure/CHD-related | 11 (64.7) | 10 (43.5) |

| Sepsis | 2 (11.8) | 1 (4.3) |

| Multiple organ system failure | 3 (17.6) | 0 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1 (5.9) | 3 (13.1) |

| Pneumonia/Other Respiratory | 0 | 6 (26.1) |

| Seizure | 0 | 2 (8.7) |

| Trauma | 0 | 1 (4.3) |

Figure 4.

Mean pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) in Trisomy 13 and 18 patients with ventricular septal defect.

Comment

The types of CHD diagnoses in this study are consistent with those reported previously [1]. Most (67%) of the cardiac surgical procedures performed in this cohort were relatively low risk (STAT risk category 1 or 2). Patients with T13 or T18 had higher mortality for both STAT 1 (6.4%), STAT 2 (25%) and STAT 4 (13%) procedures, compared to the expected mortality in the general CHD surgical population of 0.6%, 2.4%, and 9.1% respectively.[14]. Observed surgical mortality was also higher than predicted based on the RACHS-1 category for comparable procedures from the PCCC during the same era [16]. The observed mortality in the trisomic population was 8.3% for RACHS-1 category 1, 13% for RACHS-1 category 2, 12.1% for RACHS-1 category 3, and 25% for RACHS-1 category 4 procedures, compared to expected mortality of 0.6%, 2.0%, 6.4%, and 14.5%, respectively [16]. The increased observed mortality in our cohort may reflect the effect of co-morbidities, including pulmonary hypertension, in the T13 and T18 patients.

The survival models were conditioned on surviving initial CHD intervention. We utilized this strategy to focus our analysis on the sub-group that had long term survival data available. However, it is important to appreciate that procedural mortality remains high, even in patients with T13 and 18 who were considered to be acceptable candidates for intervention. Defining the ideal timing for surgical intervention, when offered, is not simple because comorbidities that are independent risk factors for mortality, such as prematurity and low birth weight, can affect this decision [6,19,20]. The 15-year survival was significantly higher for patients who underwent a corrective procedure compared to those who underwent palliative procedures only, but this may reflect more complex forms of underlying cardiac disease or more compromised pre-operative clinical status. Pulmonary hypertension may affect both short and long term outcomes and cardiac catheterization should be considered to guide treatment decisions. T18 patients appear to have increased risk of pacemaker placement after cardiac surgery (sinus node dysfunction in one patient, complete heart block in five patients).

Strengths and Limitations

Our study represents one of the largest cohorts of patients with T13 or T18 who underwent interventions for CHD with long term survival data via a national registry. However, our reported long term survival is only for patients who were discharged after intervention for CHD. Since the factors contributing to decisions about interventions are not known, our results do not reflect survival of all patients with T13 or T18 and CHD. Patients who were not offered treatment had an in-hospital mortality rate of 75%; the 18 patients discharged alive without intervention were not submitted to NDI so their vital status is unknown. Patients enrolled after stricter HIPAA rules implementation were not submitted to NDI, so their long term mortality is not reported. NDI linkage was available for 44/56 hospital survivors (80.4%) who were enrolled prior to stricter HIPAA regulations and had first and last names available, and there were relatively few linked deaths (23/44, 51.1%). The sensitivity of PCCC-NDI linkage overall is 88.1% (95% CI 87.1–89%) for patients with first and last name available [17], so our death estimates are conservative. In our small cohort, the sensitivity of the PCCC-NDI linkage was 71.4% for patients with both first and last names available, and 0% for patients without a first name available. Data on complications was limited to what was reported in the registry and may not be comprehensive.

Finally, cytogenetic reports were not included in the database, and limitations of genetic diagnosis in earlier eras may have precluded a detailed genetic diagnosis. The influence of mosaicism or partial trisomy on outcomes is important, and our results demonstrated a significant difference in survival between patients with and without reported mosaicism. Previous studies have reported that mosaic or partial forms of T13/T18 may have improved survival compared to those with full forms of trisomy [6,19].

Conclusions

This study provides insights regarding long term outcomes of patients with T13 or T18 and CHD, in candidates deemed appropriate for intervention. In-hospital mortality remains high following intervention for CHD in T13/T18 patients. Our results suggest that 10-year survival is possible for selected patients with T13 or T18 after managing their CHD. However, these patients often have complex medical needs and severe developmental disabilities; therefore, an interdisciplinary team approach including parental involvement is vital for helping families make the appropriate decision. There are important ethical issues at the individual, family, provider, and organizational level that must be considered but they are beyond the scope of this paper. These results provide updated information for providers to counsel parents of children with T13/T18 and CHD regarding expected outcomes for interventions for CHD, as well as for making program-level decisions about offering CHD intervention to these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Helen E. Hoag Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Research Endowment. Partial support: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant 5R01 HL122392-04, PI Lazaros K. Kochilas. The authors acknowledge the support of the staff from the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium staff and the participating centers.

Glossary

Abbreviation

- ASD

Atrial septal defect

- AVSD

Atrioventricular septal defect, or atrioventricular canal

- CHD

Congenital heart defect

- CoA

Coarctation of the aorta

- DORV

Double outlet right ventricle

- IAA

Interrupted aortic arch

- IQR

Interquartile range

- LOS

Length of stay

- NDI

National Death Index

- PAP

Pulmonary artery pressure

- PCCC

Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium

- PDA

Patent ductus arteriosus

- PVR

Pulmonary vascular resistance

- STAT

Society of Thoracic Surgeons-European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery Mortality risk categories

- RACHS-1

Risk Adjustment in Congenital Heart Surgery, version 1

- T13

Trisomy 13

- T18

Trisomy 18

- TGA

Transposition of the great arteries

- TOF

Tetralogy of Fallot

- VSD

Ventricular septal defect

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carey JC. Trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 syndromes. In: Cassidy SB, Allanson JE, editors. Management of genetic syndromes. 3rd. New York: Wiley-Liss; 2010. pp. 807–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham EM, Bradley SM, Shirali GS, Hills CB, Atz AM. Effectiveness of cardiac surgery in trisomies 13 and 18 (from the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium) Am J Cardiol. 2004 Mar 15;93(6):801–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen SA, Wong L-YC, Yang Q, May KM, Friedman JM. Population-based analyses of mortality in trisomy 13 and trisomy 18. Pediatrics. 2003 Apr;111(4 Pt 1):777–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Embleton ND, Wyllie JP, Wright MJ, Burn J, Hunter S. Natural history of trisomy 18. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1996 Jul;75(1):F38–41. doi: 10.1136/fn.75.1.f38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyllie JP, Wright MJ, Burn J, Hunter S. Natural history of trisomy 13. Arch Dis Child. 1994 Oct;71(4):343–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.71.4.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer RE, Liu G, Gilboa SM, Ethen MK, Aylsworth AS, Powell CM, et al. for the National Birth Defects Prevention Network Survival of children with trisomy 13 and trisomy 18: A multi-state population-based study. Am J Med Genet A. 2016 Apr 1;170(4):825–37. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muneuchi J, Yamamoto J, Takahashi Y, Watanabe M, Yuge T, Ohno T, et al. Outcomes of cardiac surgery in trisomy 18 patients. Cardiol Young. 2011 Apr;21(2):209–15. doi: 10.1017/S1047951110001848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costello JP, Weiderhold A, Louis C, Shaughnessy C, Peer SM, Zurakowski D, et al. A contemporary, single-institutional experience of surgical versus expectant management of congenital heart disease in trisomy 13 and 18 patients. Pediatr Cardiol. 2015 Jan 23;36(5):987–92. doi: 10.1007/s00246-015-1109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maeda J, Yamagishi H, Furutani Y, Kamisago M, Waragai T, Oana S, et al. The impact of cardiac surgery in patients with trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 in Japan. Am J Med Genet A. 2011 Nov;155A(11):2641–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneko Y, Kobayashi J, Achiwa I, Yoda H, Tsuchiya K, Nakajima Y, et al. Cardiac surgery in patients with trisomy 18. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009 Aug;30(6):729–34. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorenz JM, Hardart GE. Evolving medical and surgical management of infants with trisomy 18. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014 Apr;26(2):169–76. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moller JH. Using data to improve quality: the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium. Congenit Heart Dis. 2016 Feb;11(1):19–25. doi: 10.1111/chd.12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moller JH, Powell CB, Joransen JA, Borbas C. The pediatric cardiac care consortium–revisited. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1994 Dec;20(12):661–8. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien SM, Clarke DR, Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Lacour-Gayet FG, Pizarro C, et al. An empirically based tool for analyzing mortality associated with congenital heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009 Nov;138(5):1139–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins KJ, Gauvreau K, Newburger JW, Spray TL, Moller JH, Iezzoni LI. Consensus-based method for risk adjustment for surgery for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002 Jan;123(1):110–8. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.119064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vinocur JM, Menk JS, Connett J, Moller JH, Kochilas LK. Surgical volume and center effects on early mortality after pediatric cardiac surgery: 25-year North American experience from a multi-institutional registry. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013 Jun;34(5):1226–36. doi: 10.1007/s00246-013-0633-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spector LG, Menk JS, Vinocur JM, Oster ME, Harvey BA, St Louis JD, et al. In-hospital vital status and heart transplants after intervention for congenital heart disease in the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium: Completeness of ascertainment using the National Death Index and United Network for Organ Sharing Datasets. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016 Aug;5(8):e003783. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morales DLS, McClellan AJ, Jacobs JP. Empowering a database with national long-term data about mortality: The use of national death registries. Cardiol Young. 2008 Dec;18(Supplement S2):188–95. doi: 10.1017/S1047951108002916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu J, Springett A, Morris JK. Survival of trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) and trisomy 13 (Patau Syndrome) in England and Wales: 2004–2011. Am J Med Genet A. 2013 Oct;161A(10):2512–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goc B, Walencka Z, Włoch A, Wojciechowska E, Wiecek-Włodarska D, Krzystolik-Ładzińska J, et al. Trisomy 18 in neonates: Prenatal diagnosis, clinical features, therapeutic dilemmas and outcome. J Appl Genet. 2006;47(2):165–70. doi: 10.1007/BF03194617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.