Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Abstract

Problem

Academic physician reimbursement has moved to productivity-based compensation plans. To be sustainable, such plans must be self-funding. Additionally, unless research and education are appropriately valued, faculty involved in these efforts will become disillusioned, yet revenue generation in these activities is less robust than for clinical care activities.

Approach

Faculty at the Department of Medicine, University of Florida Health, elected a committee of junior and senior faculty and division chiefs to restructure the compensation plan in fiscal year (FY) 2011. This committee was charged with designing a new compensation plan based on seven principles of organizational philosophy: equity, compensation coupled to productivity, authority aligned with responsibility, respect for all academic missions, transparency, professionalism, and self-funding in each academic mission.

Outcomes

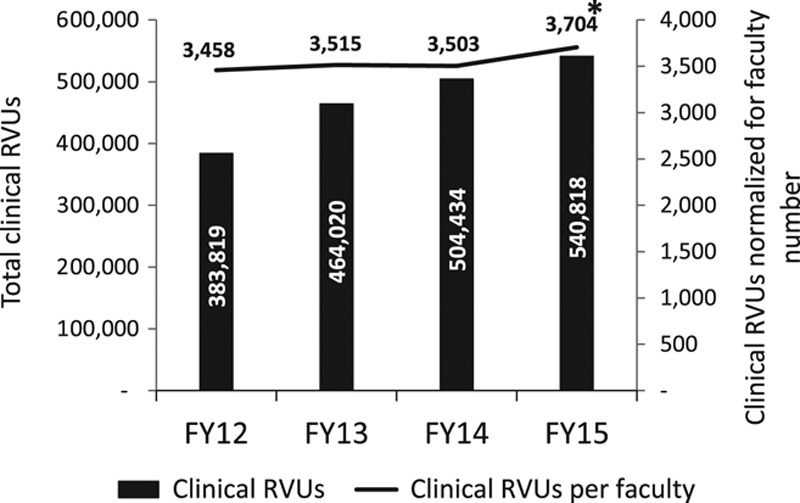

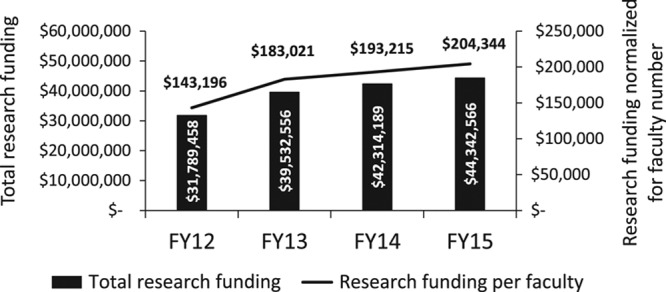

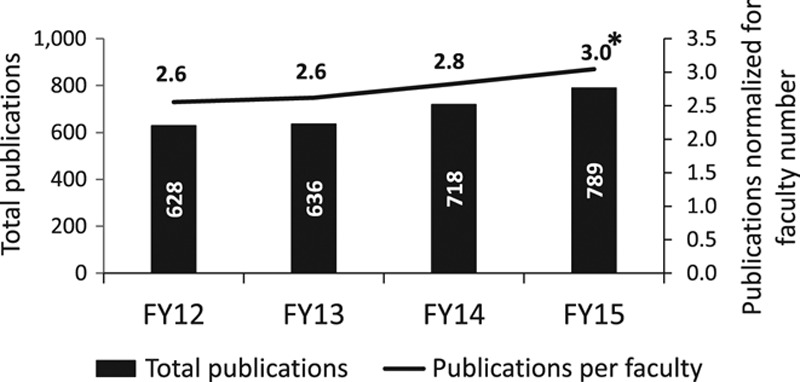

The new compensation plan was implemented in FY2013. A survey administered at the end of FY2015 showed that 61% (76/125) of faculty were more satisfied with this plan than the previous plan. Since the year before implementation, clinical relative value units per faculty increased 7% (from 3,458 in FY2012 to 3,704 in FY2015, P < .002), incentives paid per faculty increased 250% (from $3,191 in FY2012 to $11,153 in FY2015, P ≤ .001), and publications per faculty increased 15% (from 2.6 in FY2012 to 3.0 in FY2015, P < .001). Grant submissions, external funding, and teaching hours also increased per faculty but did not reach statistical significance.

Next Steps

An important next step will be to incorporate quality metrics into the compensation plan, without affecting costs or throughput.

Problem

In the last two decades, academic medicine compensation plans have evolved from fixed to variable salaries with incentives based on revenue-generating productivity.1–3 Kairouz et al1 report that 82% of departments of medicine in the United States measure some form of productivity to calculate salary compensation. This evolution was driven by prior reports that found that clinical productivity increases when faculty are incentivized with the potential to increase their compensation.1–3

Many of the early variable salary compensation plans, however, did not properly incentivize the other missions of academic medicine—research and education.4,5 Thus, these academic missions suffered under such plans; this stimulated the rise of comprehensive compensation plans that also provide incentives for research and education.3,6,7 In some of these comprehensive compensation plans, the incentives for research and education come from pooled clinical income and not from their own revenue generation.3,6,7 Although such comprehensive plans may incentivize education and research, they can place clinicians in opposition to educators and investigators, decreasing clinical productivity and harming clinical faculty recruitment and retention6,7 if clinical revenue that could be used for clinical incentives instead subsidizes research and education. In such plans, the research and education missions are often not self-funding, and thus are ultimately not self-sustaining. This can lead to inequities and faculty dissatisfaction.1–3 At the same time, though, faculty engaged in research and education become disenchanted without productivity-based incentives for those activities.1,3,8,9 Thus, productivity-based comprehensive compensation plans can place each of academic medicine’s missions in competition with the others. This competition between missions is often resolved at the level of the chair or dean, who imposes a compensation plan by fiat, which can itself lead to faculty disengagement.

New approaches are needed to design compensation plans that balance these competing missions and ensure that each remains self-funding. We hypothesized that a plan designed by an elected and empowered faculty committee, without interference from the departmental or medical school leadership, would result in increased faculty satisfaction and resolve this competition for revenue between missions.

Approach

The previous compensation plan at the Department of Medicine, University of Florida Health, assigned productivity targets for each mission based on the historical assignments of individual faculty and his/her length of time at the institution. This led to highly productive junior faculty subsidizing less productive but more senior faculty, which resulted in dissatisfaction with and distrust of leadership. To overcome that distrust, in fiscal year (FY) 2011, three assistant professors, three associate or full professors, and three division chiefs were elected by their peers to a committee to restructure the compensation plan. This committee was charged with designing a new plan based on the following seven principles of organizational philosophy: (1) equity, (2) compensation coupled to productivity, (3) authority aligned with responsibility, (4) respect for all academic missions, (5) transparency, (6) professionalism, and (7) self-funding in each academic mission.

Equity

The compensation plan was applied equally to all faculty. To counteract the contention of some faculty that they were unfairly overworked and underpaid, salary for every faculty was benchmarked at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) 50th percentile for rank, and productivity targets, as measured by relative value units (RVUs), for every specialty were benchmarked by the University Health Consortium (UHC, now Vizient) at the 50th percentile plus departmental overhead. This overhead included the cost of departmental and divisional administrative support; Family and Medical Leave Act, professional, and sick leave; fellowship administration; and billing and collecting, and came out to an additional 10% of target RVUs. No part of the plan rested on an individual’s self-reporting of effort; instead, compensation was aligned with RVUs. All educational efforts were defined by medical student or trainee schedules and were not self-reported.

Compensation coupled to productivity

By linking benchmarked salaries with benchmarked productivity targets, an individual’s effort determined his/her compensation. A given faculty member could work as little or as much as he/she desired to generate additional income. Negative salary adjustments did not occur until productivity was 10% lower than the target. This “safety corridor” was defined by the average of annual leave time, either for illness, vacation, or professional travel, taken by departmental faculty. Incentives were defined by the net positive financial margin to the department for each extra RVU generated and were paid for each RVU an individual faculty had earned above his/her annual target for all missions. There are some clinical services the institution requires that have no RVU productivity, such as medical intensive care unit attending night call or solid organ transplant care during the bundled period. In such cases, the service is supported through the contract with the hospital, with that subtracted from RVU targets.

Authority aligned with responsibility

Because under the new compensation plan RVU generation became the responsibility of the individual faculty, faculty formed small, colocalized teams and were given unprecedented control of their clinic schedules and operations. Faculty at < 75% of AAMC salary benchmarks could take half of the prior year’s incentive as a base salary increase, with their RVU targets then concurrently increased. This meant that a choice to increase salary led to increased responsibility for productivity as well. Thus, salaries generated by the plan were both self-funding and self-correcting.

Respect for all academic missions

Defining the value of education and research has traditionally been difficult for many comprehensive compensation plans.4–7 In our case, the compensation committee decided to translate all education and research efforts into RVU equivalents based on a one-minus system (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A407, pages 3–5). In this system, the RVU benchmark for a given salary and rank was set at 1, and then the fractional clinical effort was subtracted from that, leaving a fraction of RVUs that needed to be covered by educational or research effort. Educational and research productivity was measured by revenue generated from educational or research effort. If it covered that fraction of salary then it met the RVU target. If the revenue generated exceeded the target, it was converted into RVUs by dividing the excess funding by the total salary, multiplied by the total RVU target. The research target was prorated for the National Institutes of Health cap, and any research salary over that cap was covered by departmental philanthropy and residual accounts. All education or research revenue (such as state medical education funds given for teaching medical students, graduate medical education funds for postgraduate training, or external research grants or contracts) that was generated by an individual faculty was translated into RVUs, based on the average dollar per clinical RVU. The total RVUs generated by an individual faculty’s combined efforts were set by cross-matching AAMC percentile salary with UHC percentile RVUs. Some educational efforts, notably fellowship and residency administration, and most start-up and bridge research efforts, had to be internally funded, usually from foundation funds, such as the Gatorade Trust, or residual clinical revenue from the prior year. These were translated into RVUs and counted toward the annual target. However, only additional external funds could result in an incentive for that faculty. State general revenue for medical education is disbursed by the college based on face time with medical students prorated for the number of students involved. Thus, more medical student teaching effort resulted in more revenue to the department. Or, if an investigator received more revenue than needed to cover his/her research full-time equivalent salary, then the department had a decreased financial responsibility for that investigator’s salary, resulting in increased revenue to the department. All such increased revenue was pooled with clinical positive margins for incentives. Incentives for research or education were paid at the same rate as clinical incentives for every RVU an individual faculty had over his/her target.

Transparency

The compensation committee presented this compensation plan to the assembled faculty in FY2012 for suggestions, critique, and approval. Key elements that led to its approval at the department, college, and university level were that it was self-funding and equally applied, base salaries could increase as well as decrease, and faculty could modify their work schedules in real time as needed to make their targets. Faculty were provided monthly compensation plan productivity dashboards, outlining their monthly and year-to-date production of clinical, research, and educational RVUs. All expenses that made up departmental overhead were approved by the chiefs and were transparent to faculty.

Professionalism

The principle that behavior impacts the productivity of the entire department led to professionalism policies within the compensation plan. Issues that harmed departmental revenue, such as not signing clinical notes, resulted in RVU penalties to the individual faculty. However, there were several professionalism issues (such as timely completion of medical student or resident evaluations, or neglecting to cancel clinics 30 days in advance) that did not receive RVU penalties but, rather, resulted in the individual faculty losing group privileges (such as access to professional travel support or pilot project funds).

Self-funding in each academic mission

The compensation committee was charged with creating a plan in which all incentives and salary increases would be offset by incremental revenue growth. Thus, only productivity counted toward compensation, not time expended. By varying overhead RVUs to cover agreed-upon expenses, by benchmarking salaries to RVU equivalents, and by paying incentives based on incremental revenue generated (see above), the compensation plan became self-funding.

The full compensation plan and further details are available in Supplemental Digital Appendixes 1 and 2 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A407 and http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A408.

Outcomes

The first year after the plan’s implementation (FY2013) was administratively challenging, given the variables for compensation. However, the plan has since been automated, and individual electronic dashboards of schedules and productivity targets are available in real time on a secure intranet. These dashboards are automatically populated after assignments and budgets are set. Examples of dashboards are available on request.

In the three years since this faculty-generated, self-funding, comprehensive compensation plan has been imple-mented, not only have clinical productivity increased and research and educational metrics remained steady, but incentives paid to faculty annually have nearly tripled (see below). The departmental margin after incentives went from negative $245,490 in FY2012 (the year prior to implementation) to positive $4.7 million in FY2015 (three years after implementation), and costs went from $104/RVU in FY2012 to $94/RVU in FY2015.

We created a robust statistical method to analyze productivity trends for the plan. For each year we calculated a personal slope via least squares for the productivity measure, which represented the change in the measure per year. This collection of slopes was then analyzed via descriptive statistics: mean, standard deviation, and quartiles. Because these data are highly prone to outliers and thus potentially skewed, the usual parametric methods including linear mixed models were deemed inappropriate. We therefore used the nonparametric Wilcoxon sign-rank test to assess the significance of these trends against the null hypothesis that the trends are symmetric about zero. All P values are two sided.

Clinical productivity

Clinical RVUs normalized per faculty number rose 7% since the year before implementation, from 3,458/faculty in FY2012 to 3,704/faculty in FY2015 (P < .002, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Total and normalized for faculty number clinical relative value units (RVUs) for the year prior to (fiscal year [FY] 2012) and three years after implementation (FY2013–FY2015) of the Department of Medicine, University of Florida Health, compensation plan. Asterisk indicates P < .002.

Research productivity

Grant submissions normalized per faculty number rose by 46% since the year before implementation, from 1.3 in FY2012 to 1.9 in FY2015, but did not reach statistical significance (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 3 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A408). Total external research funding (all grants and contracts from any external source for any research activity) rose by 43% since the year before implementation, from $143,196 in FY2012 to $204,344 in FY2015, but when normalized for faculty number did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2). Publications per faculty rose by 15% since the year before implementation, from 2.6 in FY2012 to 3.0 in FY2015 (P < .001, Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Total and normalized for faculty number external research funding for the year prior to (fiscal year [FY] 2012) and three years after implementation (FY2013–FY2015) of the Department of Medicine, University of Florida Health, compensation plan (not significant).

Figure 3.

Total and normalized for faculty number publications for the year prior to (fiscal year [FY] 2012) and three years after implementation (FY2013–FY2015) of the Department of Medicine, University of Florida Health, compensation plan. Asterisk indicates P < .001.

Educational productivity

Teaching hours normalized for faculty number rose by 8% over the three years of the plan, from 90.83 in FY2013 to 98.43 in FY2015, but did not reach statistical significance (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 4 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A408). Quality of teaching was rewarded outside of the compensation plan with philanthropic monetary awards based on medical student, resident, and fellow evaluations.

Faculty satisfaction

There were no changes in faculty recruitment, retention, or promotion rates in the three years after implementation (FY2013–FY2015). At the end of FY2015, an interactive survey was administered to an audience of 125 faculty at a departmental retreat. Sixty-one percent (76/125) of faculty were more satisfied with the new compensation plan as compared with the previous plan. The survey also found that 66% (82/125) of faculty believed the professionalism standards within the plan were fair in content, and 61% (76/125) indicated the standards were fair in application.

Incentives

Average incentives earned per faculty increased 250% since the year before implementation, from $3,191 in FY2012 to $11,153 in FY2015 (P ≤ .001, see Supplemental Digital Appendix 5 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A408).2,3 The first year after implementation (FY2013), 67% (85/127) of eligible faculty accepted their base salary increase and the attendant RVU target increase, while the third year after implementation (FY2015), 55% (53/96) accepted their base salary increase and the attendant RVU target increase. In FY2013, 3% (6/216) of faculty received negative salary adjustments, while 1% (2/219) and 0.5% (1/217) received negative salary adjustments in FY2014 and FY2015, respectively. Four of those six FY2013 faculty had previously held significant administrative posts but had retained the same salary even though they had left those posts. Before the plan was implemented (FY2012), 35% (77/222) of faculty received incentives. After implementation, 50% (107/216), 58% (128/219), and 65% (140/217) of faculty received incentives in FY2013, FY2014, and FY2015, respectively.

Next Steps

There were statistically significant improvements in the RVUs earned and incentives paid per faculty in this faculty-generated, self-sustaining, comprehensive compensation plan. Additionally, about two-thirds of faculty were more satisfied with the new compensation plan as compared with the old one. Whereas other studies have shown that external research funding, grant submissions, and publications all increased per faculty after compensation plans rewarding research were initiated,5–7 in our experience here, though they all increased, only the increase in publications per faculty reached statistical significance. Unlike most other plans, the plan here is self-funding and thus self-sustaining. Of course, the reasons for these changes may be due to factors other than the new compensation plan, such as improved insurance contract rates, state legislative support, or hospital support. Nevertheless, taken together, these measures seem to suggest that the compensation plan helped to resolve competition for revenue between the missions.

A just compensation plan is a major contributor to a positive department culture.8,9 For most faculty, their absolute compensation is less important than their relative compensation—the knowledge that they are being compensated fairly compared with their peers.4–6 Thus, aligning salaries and RVU targets to national benchmarks can decrease much of the discontent with compensation plans.1,4

The rapid increase in incentives, which were self-funded, paid with this plan has stimulated other departments within our institution to adopt many of the aspects of this compensation plan, such as automated salary adjustments up or down based on benchmarked productivity rather than time assigned. Other aspects of this compensation plan, such as penalties for unprofessionalism or faculty’s ability to control their schedules, have been more difficult to generalize to other departments.

The opposing national trajectories of salary and RVU benchmarks over time are concerning. AAMC salaries are increasing while UHC RVU benchmarks are decreasing. Unless reimbursement per RVU in all missions keeps pace with these salary increases, departmental overhead in our plan will rise, increasing targets. This will be a challenge for all of academic medicine.

An important next step will be to incorporate quality metrics into the compensation plan, without affecting costs or throughput. Financial incentives for clinical productivity have been postulated to put quality of care at risk.1,4 However, a systematic review found that six of seven appropriately conducted studies showed positive but modest effects on the quality of care for a majority of, but not all, primary outcomes.10 Thus, rewarding defined quality outcomes must be carefully incorporated into compensation plans to achieve improvement.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this manuscript. There was no off-label or investigational use.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Previous presentations: Oral presentation at the University Hospital Consortium Annual Conference, June 7, 2012, San Antonio, Texas; Association of Health Centers Joint Executive Group Meeting, December 6, 2012, Washington, DC; Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine Educational Conference, October 4, 2013, New Orleans, Louisiana; and Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine Educational Conference, October 9, 2015, Atlanta, Georgia.

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A407 and http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/A408.

References

- 1.Kairouz VF, Raad D, Fudyma J, Curtis AB, Schünemann HJ, Akl EA. Assessment of faculty productivity in academic departments of medicine in the United States: A national survey. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller RD, Cohen NH. The impact of productivity-based incentives on faculty salary-based compensation. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:195–199.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reece EA, Nugent O, Wheeler RP, Smith CW, Hough AJ, Winter C. Adapting industry-style business model to academia in a system of performance-based incentive compensation. Acad Med. 2008;83:76–84.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akl EA, Meerpohl JJ, Raad D, et al. Effects of assessing the productivity of faculty in academic medical centres: A systematic review. CMAJ. 2012;184:E602–E612.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mets B, Eckerd K. Faculty incentive plans: Clinical or academic productivity or both? Anesth Analg. 2006;102:968–969.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakai T, Hudson M, Davis P, Williams J. Integration of academic and clinical performance-based faculty compensation plans: A system and its impact on an anaesthesiology department. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:636–650.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holcombe RF, Hollinger KJ. Mission-focused, productivity-based model for sustainable support of academic hematology/oncology faculty and divisions. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:74–79.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girdhari R, Harris A, Fallis G, Aliarzadeh B, Cavacuiti C. Family physician satisfaction with two different academic compensation schemes. Fam Med. 2013;45:622–628.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trowbridge E, Bartels CM, Koslov S, Kamnetz S, Pandhi N. Development and impact of a novel academic primary care compensation model. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1865–1870.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott A, Sivey P, Ait Ouakrim D, et al. The effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD008451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]