Highlights

-

•

Prototyping is efficient for surgical zygomatic-orbital correction.

-

•

The use of preshaped titanium plates reduces operative time and improves esthetics.

-

•

Prototyping provides a better outcome for the patient than conventional surgery.

Keywords: Orbital fractures, Orbit, Fracture fixation, Prototyping, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Zygomatic-orbital complex fractures are the most common facial traumas that can result in severe esthetic and functional sequelae. Surgical correction of these fractures is a delicate approach and prototyping is an excellent tool to facilitate this procedure.

Presentation of case

A 27-year-old man, a motorcycle accident victim, was hospitalized in the intensive care unit for 30 days. After this period, facial fractures were treated surgically, leaving sequelae such as enophthalmos, dystopia and loss of projection of the zygomatic arch. A second intervention was planned after one year for reconstruction of the orbit with the help of prototyping. Better outcomes were achieved than in the first intervention.

Discussion

This report permits to compare the result of conventional surgery and the use of a prototype in the same patient. Noticeably better outcomes were achieved with the second approach. Prototyping made the surgical procedure more predictable and reduced operative time because of the possibility of using preshaped titanium plates.

Conclusions

Prototyping was found to be an excellent option to overcome the deficiencies of the conventional technique, recovering the functional and esthetic characteristics of the patient’s face and ensuring a markedly satisfactory outcome.

1. Introduction

Surgical reduction of zygomatic-orbital complex fractures is generally challenging for the surgeon because of the lack of an occlusal guide and the involvement of various structures of the middle third of the face [1]. Severe esthetic and functional sequelae can occur in cases of trauma to this region, including enophthalmos and diplopia, as a result of swelling of the orbit due to orbital floor fracture and herniation of the ocular content into the maxillary sinus [2], [3].

Excellent results in the treatment of these sequelae are observed for reconstruction of the orbital floor with titanium meshes and stable internal fixation with mini-plates using rapid prototyping for surgical planning [4]. The use of prototypes in oral and maxillofacial surgery has benefits such as greater predictability, more detailed planning and a shorter operative time because of the possibility of using preshaped plates [5], [6], [7].

For better planning of reconstructions of the contour and volume of the orbit, the so-called mirror image technique, in which the software is able to mirror the healthy hemiface and print the intended bone framework, has become a useful tool. Thus, the surgeon can plan the procedure from a prototype exactly corresponding to the way he intends the patient to look after surgery [1], [8].

The objective of this study was to report a case of orbit reconstruction for correction of an esthetic defect caused by severe injury to the zygomatic-orbital region using prototyping for surgical planning and optimization. This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [9].

2. Presentation of case

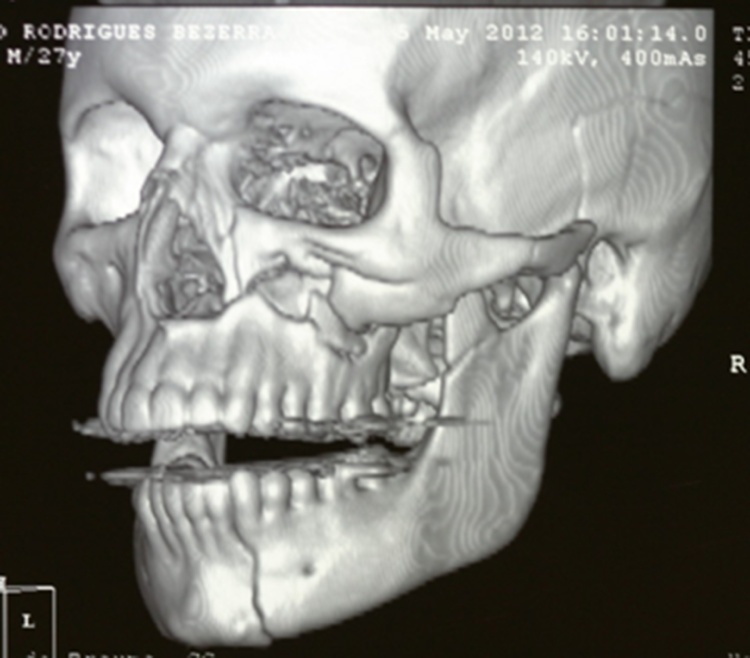

A 27-year-old white male patient, a motorcycle accident victim, was brought by an ambulance to the emergency department of a public trauma hospital in Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brazil. The patient presented with fractures in the mandible, maxilla and left zygomatic-orbital complex, in addition to traumatic temporal lobe damage. In view of other morbidities, the patient remained hospitalized in the intensive care unit receiving neurosurgical care for 30 days. After this period, healing of the facial fractures had already progressed substantially (Fig. 1) and the patient was referred to the oral and maxillofacial sector of the hospital. A first intervention of the face was performed after analysis of the images and preoperative exams. In this procedure, the oral and maxillofacial surgeon aimed at reduction and fixation of the fractures.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan showing fractures in the zygomatic bone, maxilla and mandible after trauma.

After one year, the patient sought the team because of esthetic complaints in the left eye. Physical examination revealed the presence of enophthalmos, dystopia, deficient projection of the zygomatic bone, facial nerve damage and amaurosis, which resulted in a perceptible esthetic defect and discomfort to the patient (Fig. 2). The mandibular fractures had healed satisfactorily and no occlusal alterations were observed.

Fig. 2.

Frontal view of the patient one year after the first surgical intervention. Note the presence of enophthalmos, dystopia and deficient projection of the zygomatic bone.

The computed tomography images were updated, digitized, and sent to the Renato Ascher Information Technology Center. A mirror image was produced with the Invesalius 3 Beta 4 software, dividing the image in the midline of the face and reproducing the healthy side to obtain a perfect and symmetric model of the face. After image editing, a prototype was printed in resin that reliably reflected the bone structure of the patient (Fig. 3). Next, surgical planning aimed at sectioning and correct repositioning of the zygomatic bone was performed, including pre-shaping of the plates and fixation in the model (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Surgical planning using titanium plates and meshes.

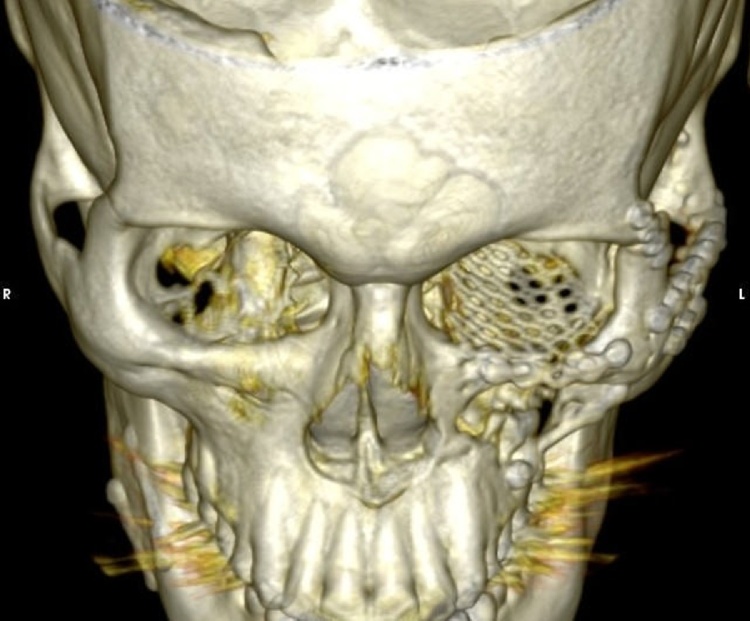

Surgery consisted of a coronal incision for complete exposure of the zygomatic bone and sectioning along the frontozygomatic suture, lateral wall of the orbit, zygomatic arch and zygomaticomaxillary region. A subciliary incision was made to gain access to the orbital floor and an intraoral approach was used for visualization and fixation in the zygomaticomaxillary region. A system of 2.0-mm titanium plates with monocortical screws was applied (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Computed tomography scan obtained after the second surgical intervention.

Postoperative recovery occurred without intercurrences. During the return visit 40 days after the surgical procedure, the patient showed considerable improvement, with alignment of the orbits, absence of enophthalmos and dystopia and satisfactory projection of the zygomatic arch. The postoperative outcomes were satisfactory, permitting functional and esthetic rehabilitation of the patient (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Frontal view of the patient 40 days after surgery.

3. Discussion

The patient of this case report presented with sequelae of a previous zygomatic complex fracture and destruction of the orbital floor, which led to healing of the zygomatic bone in an undesired position, including the loss of projection and a defect in the lateral wall of the orbit [10]. Fractures of the orbital bones and zygomatic bone can cause undesirable esthetic sequelae in the patient. In this respect, techniques such as prototyping have provided successful results and its use has become increasingly important [11].

In this study, it was possible to compare the surgical outcome in the same patient since he was treated in two ways, with and without prototyping, and a noticeably better outcome was achieved when prototyping was used. Similarly, Kozakiewciz et al. [8] compared 24 patients with orbital fractures who had some sequela such as enophthalmos, dystopia and diplopia. Twelve patients were treated traditionally by manual manipulation of the titanium plate during surgery, while a preshaped titanium mesh reconstructed from a rapid prototyping model was used in the other 12 patients. The authors observed improvement during the immediate and late postoperative period for patients receiving the preshaped mesh, especially in terms of the correction of diplopia and dystopia.

In a retrospectively study of 97 patients with traumatic orbital defects treated with preshaped meshes using a rapid prototyping model for surgical planning, Huang et al. [12] achieved precise restoration of the orbital shape in practically the whole sample. Only six patients had an unsatisfactory facial appearance or enophthalmia. This proportion was significantly lower than that observed among patients whose orbital walls were reconstructed by surgery. Likewise, Mustafa et al. [4] treated 22 patients with diplopia and/or enophthalmia using plates preshaped from the prototype of an orbital mirror image. Significant success during the immediate postoperative period was achieved for most patients. In the conventional approach, the shaping and adaptation of the titanium plates to the bone at the time of surgery are time consuming and more difficult.

In the present study, the time that had elapsed after trauma posed an additional difficulty for correct rehabilitation. Surgical reconstruction of the late fracture was not successful in the first intervention because of bone healing at the site of injury and inadequate planning. Such procedure can be performed in cases of emergency and when the necessary tools are available. For example, Kanno et al. [13] performed immediate reconstruction of the orbital floor using a fragment of the fractured anterior maxillary sinus wall. The procedure was successful, in contrast to the present case in which the result of the first intervention was unsatisfactory considering that it was performed late.

With respect to ocular sequelae, there was significant improvement of dystopia and enophthalmos. It was not possible to reverse the condition of amaurosis since it was a consequence of the previous trauma. This fact has been studied by Jaquiéry et al. [3] who compared 72 patients with orbital defects. Among other factors, the authors analyzed pre- and postoperative ophthalmological conditions and observed that ophthalmological complications can be corrected within 9–12 months after surgery.

According to Brito et al. [7], the use of prototyping for surgical planning and diagnosis has become essential to achieve more predictable and successful outcomes. Although prototyping is a common tool in countries with high economic and human development indices, its use is restricted in countries such as Brazil because of its high cost and the need of complex technological development involving medicine and engineering for these purposes.

4. Conclusion

Conventional treatment of zygomatic complex fractures does often not provide a satisfactory esthetic outcome and a more detailed approach and planning are necessary in these cases. In the present case, prototyping was found to be an excellent option to overcome the deficiencies of the initially applied conventional technique, recovering functional and esthetic characteristics of the patient’s face and ensuring a markedly superior outcome.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

Since this was a clinical case seen in the hospital setting by professionals working at the same institution, the study was not submitted to approval by an ethics committee. This conduct is common in Brazil for the report of clinical cases. However, consent was obtained from the patient for treatment and publication of the results.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Authors’ contribution

All authors contributed to the study concept, data collection, and analysis and interpretation of the results. Rafael Grempel and Hécio Morais elaborated and performed the treatment plan for the patient. Nadja Brito and Amanda do Ó developed the prototype for surgical planning. Amanda do Ó wrote the manuscript. Isabella Dias and Daliana Gomes revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Guarantor

All authors accept full responsibility for the work, declare that they had access to the data, and decided to publish the work.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Núcleo de Tecnologias Estratégicas em Saúde (NUTES), Universidade Estadual da Paraíba, for permitting the fabrication of the prototype used in this study.

References

- 1.Feng F., Wang H., Guan X., Tian W., Jing W., Long J. Mirror imaging and preshaped titanium plates in the treatment of unilateral malar and zygomatic arch fractures. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2011;112:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer B., Zizelman C., Scheufler K. Solid modeling in surgery of the anterior skull base. Oper. Tech. Otolaryngol. 2010;21:96–99. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaquiéry C., Aeppli C., Cornelius P., Palmowsky A., Kunz C., Hammer B. Reconstruction of orbital wall defects: critical review of 72 patients. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007;36:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mustafa S.F., Evasn P.L., Bocca A., Patton D.W., Sugar A.W., Baxter C.P.W. Customized titanium reconstruction of post traumatic orbital wall defects a review of 22 cases. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011;40:1357–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen A., Laviv A., Berman P., Nashef R., Abu-Tair J. Mandibular reconstruction using stereolithographic 3-dimensional printing modeling technology. Sur. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2009;108:661–666. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ailed W., Watson J., Sidebottom A.J., Hollows P. Development of in-house rapid manufacturing of three-dimensional models in maxillofacial surgery. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010;48:479–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brito N.M.S.O., Soares R.S.C., Monteiro E.L.T., Martins S.C.R., Cavalcante J.R., Grempel R.G. Additive manufacturing for surgical planning of mandibular fracture. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2016;50:348–353. doi: 10.15644/asc50/4/8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozakiewicz M., Elgalal M., Loba P., Komunski P., Arkuszewski P., Broniarczyk A. Clinical application of 3D pre-bent titanium implants for orbital floor fractures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009;37:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellis E., Tan Y. Assessment of internal orbital reconstructions for pure blow out fractures: cranial bone grafts versus titanium mesh. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003;61:442–453. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell R.B., Markiewicz M.R. Computer assisted planing, stereolithographic modeling and intraoperative navigation for complex orbital reconstruction: a descriptive study in a preliminary cohort. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009;67:2259–2270. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang L., Ling L., Wang Z., Shi B., Zhu X., Qiu Y. Personalized reconstruction of traumatic orbital defects based on precise three-dimensional orientation and measurements of the globe. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2017;28:172–179. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanno T., Sukegawa S., Takabatake K., Takahashi Y., Furuki Y. Orbital floor reconstruction in zygomatic-orbital-maxillary fracture with a fractured maxillary sinus wall segment as useful bone graft material. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Med. Pathol. 2013;25:28–31. [Google Scholar]