Abstract

Setting: Seven pilot sites in Zimbabwe implementing 6 months of isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) for people living with the human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV).

Objectives: To determine, among PLHIV started on IPT, the completion rates for a 6-month course of IPT and factors associated with non-adherence.

Design: A retrospective cohort study.

Results: Of 578 patients, 466 (81%) completed IPT. Of the 112 patients who failed to complete IPT, 69 (60%) were lost to follow-up, 30 (27%) stopped treatment with no documented reasons, 8 (7%) developed toxicity/adverse reactions, 5 (5%) were documented as having drug stock-outs and the remainder transferred out or refused to continue treatment. Currently being on antiretroviral therapy (ART) (aOR 0.09, 95%CI 0.03–0.28) and receiving a ⩾2 month supply of isoniazid at the start of treatment were associated with a lower risk of not completing IPT, while missing clinic visits prior to starting IPT (aOR 5.25, 95%CI 2.10–13.14) was associated with a higher risk of non-completion.

Conclusion: IPT completion rates in seven pilot sites of Zimbabwe were comparatively high, showing that IPT roll-out in public health facilities is feasible. Enhanced adherence counselling or active tracing among pre-ART patients and those with a history of loss to follow-up may improve IPT completion rates, along with synchronising IPT and ART resupplies.

Keywords: human immunodeficiency virus, IPT, Zimbabwe, TB

Abstract

Contexte : Sept sites pilotes au Zimbabwe mettant en œuvre le traitement préventif par isoniazide de 6 mois (TPI) pour les personnes vivant avec le virus de l'immunodéficience humaine VIH (PVVIH).

Objectifs : Déterminer, parmi les PVVIH ayant mis en route le TPI : les taux d'achèvement du traitement de 6 mois et les facteurs associés avec le non achèvement.

Schéma : Etude rétrospective de cohorte.

Résultats : Sur 578 patients, 466 (81%) ont achevé le TPI. Sur 112 patients qui n'ont pas achevé le TPI, 69 (60%) ont été perdus de vue, 30 (27%) ont arrêté le traitement sans raison documentée, 8 (7%) ont eu des problèmes de toxicité/d'effets secondaires, 5 (5%) ont eu un problème documenté de rupture de stock et le reste a déménagé ou refusé de continuer le traitement. Les facteurs associés avec un risque plus faible de ne pas achever le TPI ont été le fait d'être parallèlement sous traitement antirétrovirale (TAR) (odds ratio ajusté [ORa] 0,09 ; IC95% 0,03–0,28) et le fait de recevoir plus de 2 mois de stock d'isoniazide au début du traitement, tandis que l'absence aux rendezvous de consultation avant la mise en route du TPI (ORa 5,25 ; IC95% 2,10–13,14) a été associé avec un risque plus élevé de non achèvement.

Conclusion : Les taux d'achèvement du TPI dans sept sites pilotes du Zimbabwe ont été comparativement élevés, ce qui montre que le déploiement du TPI dans des structures de santé publique est faisable. Une amélioration des conseils en vue de l'adhésion ou une recherche active des patients avant le TAR et de ceux qui ont des antécédents d'abandon, ainsi qu'une synchronisation des fournitures de TPI et de TAR, pourraient améliorer les taux d'achèvement.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: Siete establecimientos en Zimbabue que participaron en un ensayo preliminar del tratamiento preventivo con isoniazida (TPI) de 6 meses en personas viviendo con el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (PVVIH).

Objetivo: Determinar las tasas de finalización del TPI de 6 meses de duración y los factores que se asocian la falta de compleción del mismo en las PVVIH.

Método: Un estudio retrospectivo de cohortes.

Resultados: De los 578 pacientes estudiados, 466 terminaron el ciclo de TPI (81%). De 112 pacientes que no completaron el tratamiento, 69 se perdieron durante el seguimiento (60%), 30 interrumpieron el tratamiento sin que exista un registro de la razón (27%), 8 presentaron reacciones tóxicas o efectos adversos de los medicamentos (7%), en 5 se registró un desabastecimiento de medicamentos (5%) y los demás se transfirieron a otros centros o rehusaron la continuación el tratamiento. Los factores asociados con un menor riesgo de no completar el TPI fueron el hecho de estar recibiendo tratamiento antirretrovírico (TAR) (cociente de posibilidades ajustado [ORa] 0,09; intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95% 0,03–0,28) y el hecho de recibir una reserva de isoniazida para ⩾2 meses al comienzo del ciclo, y el factor que se asoció con un mayor riesgo de no finalizar el tratamiento fue cuando el paciente había incumplido citas médicas antes de comenzar el tratamiento (ORa 5,25; IC95% 2,10–13,14).

Conclusión: Las tasas de finalización del TPI en los siete centros pilotos de Zimbabue fueron relativamente altas e indican que es factible desplegar esta iniciativa en los establecimientos públicos de salud. Es posible mejorar las tasas de finalización con un refuerzo de la orientación sobre la observancia terapéutica, el seguimiento activo de los usuarios que no han iniciado el TAR y los que tienen antecedentes de incumplimiento y con la sincronización del reaprovisionamiento del TPI y el TAR.

Since the early 1980s, a deadly synergy between tuberculosis (TB) and HIV/AIDS (human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune-deficiency syndrome) has been established, with HIV/AIDS greatly increasing the risk of progression to active TB.1 Of the 10.4 million people globally estimated to have TB in 2015, 1.8 million died from the disease; of these, 400 000 (22%) were HIV co-infected.2 Of all recorded TB cases in 2015, 11% (1.2 million cases) were HIV co-infected; the proportion was highest in the World Health Organization (WHO) African Region countries, exceeding 50% in parts of southern Africa, including Zimbabwe.2

To mitigate the dual burden of TB-HIV, the WHO has issued guidelines3–5 that include the implementation of the ‘Three I's’ (infection control, isoniazid preventive therapy [IPT] and intensified TB case finding [ICF]) and antiretroviral therapy (ART) aimed at reducing TB prevalence in people living with HIV (PLHIV). Zimbabwe is a high TB-HIV prevalence country, with an estimated TB incidence of 242 cases per 100 000 population in 20152 and an HIV co-infection rate of 70%.2 IPT alone can reduce the risk of TB in PLHIV by up to 46%,6 and this rate can be increased further by the TB preventive effects of ART.7

Based on this evidence, and following the release of the 2011 WHO guidelines on ICF and IPT,5 Zimbabwe commissioned a 1-year pilot of ICF and IPT at 10 public clinics providing ART to PLHIV. This pilot aimed to explore and document effective practical health delivery models for offering IPT subsequent to national roll-out. Health-care workers from the respective health institutions were trained in ICF and IPT monitoring and evaluation and medicine management skills in preparation for the pilot, and post-training support and mentorship were offered. While a full course of IPT has been shown to reduce the risk of TB in PLHIV, its uptake has generally been poor, with concerns about the treatment completion rates being reported in Uganda8 and Botswana.9

To inform the Ministry of Health about the feasibility of continued scale-up of IPT to other public ART clinics countrywide, we sought to determine, among PLHIV commenced on IPT, 1) the completion rates for a full course of IPT, and 2) factors associated with non-completion of IPT.

METHODS

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study using routinely collected programme data.

Study setting

This study was conducted in seven of the 10 ART clinics that were piloting the roll-out of 6 months of IPT to PLHIV enrolled at these clinics. Three of the ART sites were at polyclinics in the capital city of Harare, three were at polyclinics in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe's second-largest city, and one was at Shurugwi district hospital, the referral hospital for Shurugwi rural district. All seven health facilities offer general health services that are integrated with TB and HIV treatment services. The three pilot ART clinics excluded from the study enrolled HIV-infected individuals on IPT after 1 March 2013 and thus did not meet the study inclusion criteria.

ICF, IPT initiation and enrolment in ART care

All confirmed PLHIV in Zimbabwe are enrolled at ART clinics to receive HIV treatment and care services. According to Zimbabwe's national IPT guidelines,10 all PLHIV should be screened for active TB at every clinic visit or every encounter with a health worker, using the WHO-recommended four-symptom TB screening checklist.11 If PLHIV present with any of the four symptoms, they are considered to be presumptive TB cases and sputum specimens are collected for smear microscopy or Xpert® MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) testing. Those patients negative on Xpert or smear microscopy and who have no other symptoms or signs of extra-pulmonary or smear-negative pulmonary TB, including chest radiography if necessary, are not recorded as having active TB.

During the pilot phase, PLHIV who were not diagnosed with active TB were offered adherence counselling and were started on a daily oral dose of isoniazid (INH, 5 mg/kg body weight for adults or 10 mg/kg body weight for children) plus a daily low dose of pyridoxine (25 mg/day) for a 6-month period, regardless of their ART status. It was recommended that patients receive regular supplies of INH every month until completion of their prophylactic treatment.10 During clinic visits, patients were assessed through self-reporting and pill counts for adherence and screened for TB. Patients found to have active TB were taken off IPT and treated according to the national TB guidelines.11

Data on TB status (screened with no TB signs/not screened/presumptive TB case/active TB), IPT status (yes/no), IPT quantity dispensed and reasons for starting or stopping IPT were integrated into the individual patient opportunistic infection (OI) ART care booklets and the pre-ART or ART registers, depending on the patients' ART status. This information was updated during each clinical review visit. For easier tracing of all clients enrolled on IPT, some pilot sites developed improvised IPT registers. As the routinely reported indicators from these data obtained through the monthly HIV progress reports to national level were ‘number started on IPT’ and ‘number completed IPT’, regardless of cohort, it was not readily possible to determine the proportion that completed IPT per cohort.

During the study period, Zimbabwe followed the 2010 WHO guidelines for initiating PLHIV on ART,12 with the preferred first-line regimen for adults, adolescents, and older children consisting of tenofovir+lamivudine+nevirapine.

Patient sample

The patient sample included all confirmed PLHIV enrolled for HIV treatment and care services and commenced on IPT at the seven selected ART clinics between 31 December 2012 and 1 March 2013.

Data variables, data source and data collection

Data collection was conducted by seven national-level TB and HIV programme officers trained on data collection processes over 2 days. Data on demographic and clinical characteristics were abstracted from individual patient ART care booklets into standardised data collection forms between 2 April and 17 May 2014 at the seven ART clinics. Information was also collected on the quantity of IPT dispensed at each visit throughout the IPT course and the follow-up visit status of the patients in the year prior to initiating IPT. Non-completion of IPT was defined as having collected the INH pills for less than the required 6-month course or having collected the INH pills during the full 6-month course but failing to return for the end-of-treatment scheduled review.

INH stock cards at each health facility dispensary were also reviewed for evidence and duration of stock-outs during the study period.

Statistical analyses

All abstracted data were coded and single-entered electronically into EpiData v. 3.1 (Epidata Association, Odense Denmark), and then exported to Stata v. 13.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) for data cleaning and statistical analyses. Proportions were generated for categorical variables, and comparisons were made between those who did and those who did not complete IPT using the χ2 test for associations. Variables that produced a P value < 0.25 for χ2 associations with IPT non-completion were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine risk factors associated with IPT non-completion, which were reported using adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Levels of significance were set at 0.05.

Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe, Harare, and the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France. As this study used secondary data, informed patient consent was not required.

RESULTS

Characteristics

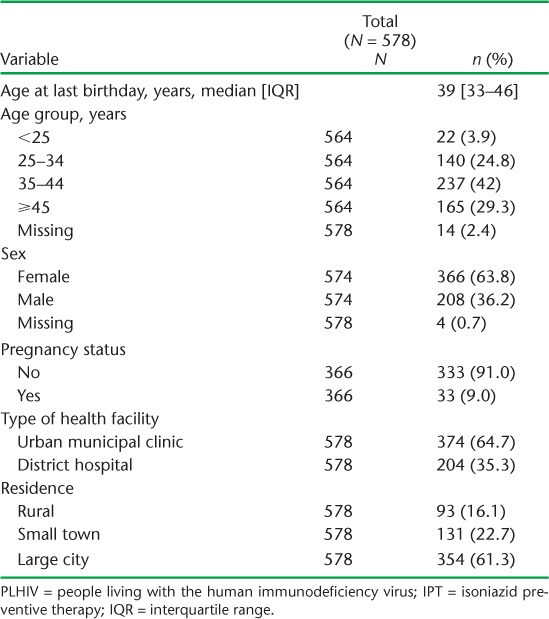

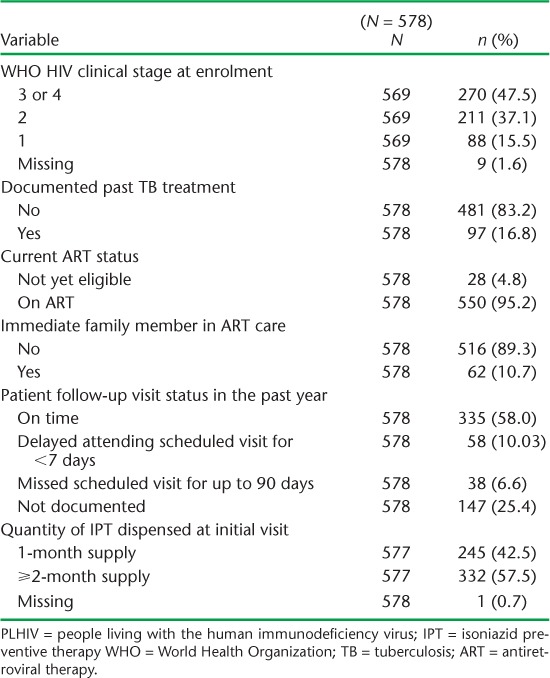

Over the 2-month period from 31 December 2012 to 1 March 2013, 578 PLHIV were started on IPT. Table 1 shows the patients' demographic characteristics and Table 2 shows their clinical characteristics. The median age was 39 years (interquartile range [IQR] 33–46). Two thirds of the patients were female; most resided in urban areas. Nearly half were in WHO clinical stage 3 or 4 at the time of enrolment into care, and 95% were undergoing ART at the time of IPT initiation. Nearly 60% of the patients had consistently been punctual for their scheduled review visits in the year prior to starting IPT.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of PLHIV commenced on IPT

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics of PLHIV commenced on IPT

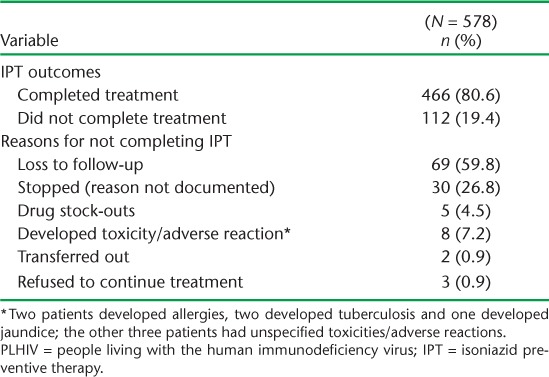

Receipt of drugs and outcomes of isoniazid preventive therapy

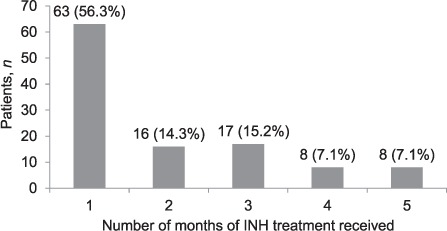

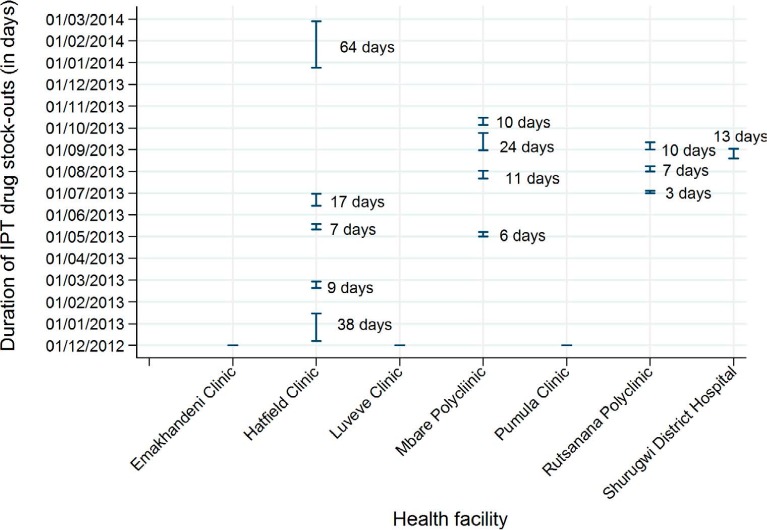

Of the PLHIV who started IPT, only 245 (42%) received a 1-month supply of drugs as recommended on their first visit, while 333 (58%) received a ⩾2 month supply. Outcomes of the 6-month IPT course and reasons for non-completion are shown in Table 3. Among the 112 (19%) PLHIV who did not complete the 6-month IPT course, the main reasons were loss to follow-up (n = 69, 60%) and stopping treatment with undocumented reasons (n = 30, 27%). More than half (56%) stopped treatment after receiving a 1-month supply of INH, while respectively 16 (14%) and 17 patients (15%) stopped treatment after receiving 2-month and 3-month supplies of treatment (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows the frequency and duration of the IPT drug stock-outs at the seven health facilities between 1 December 2012 and 31 March 2014. There were a total of 13 episodes of drug stock-outs for a median duration of 9.5 days (IQR 4.5–15). The Hatfield clinic had the most frequent drug stock-outs, followed by the Mbare polyclinic and the Rutsanana polyclinic, all located in Harare.

TABLE 3.

Outcomes of PLHIV enrolled on IPT in Zimbabwe

FIGURE 1.

Number of months of INH treatment received by patients who did not complete IPT. INH = isoniazid; IPT = isoniazid preventive therapy.

FIGURE 2.

Duration and frequency of IPT drug stock-outs by health facility* (1 December 2012–31 March 2014). * Rutsanana, Hatfield, Mbare and Shururgwi District Hospital clinics had stock-outs: Hatfield and Mbare clinics had stock-outs respectively five and four times during the study period. Emakhanden, Luveve and Pumula clinics had no stock-outs. IPT = isoniazid preventive therapy.

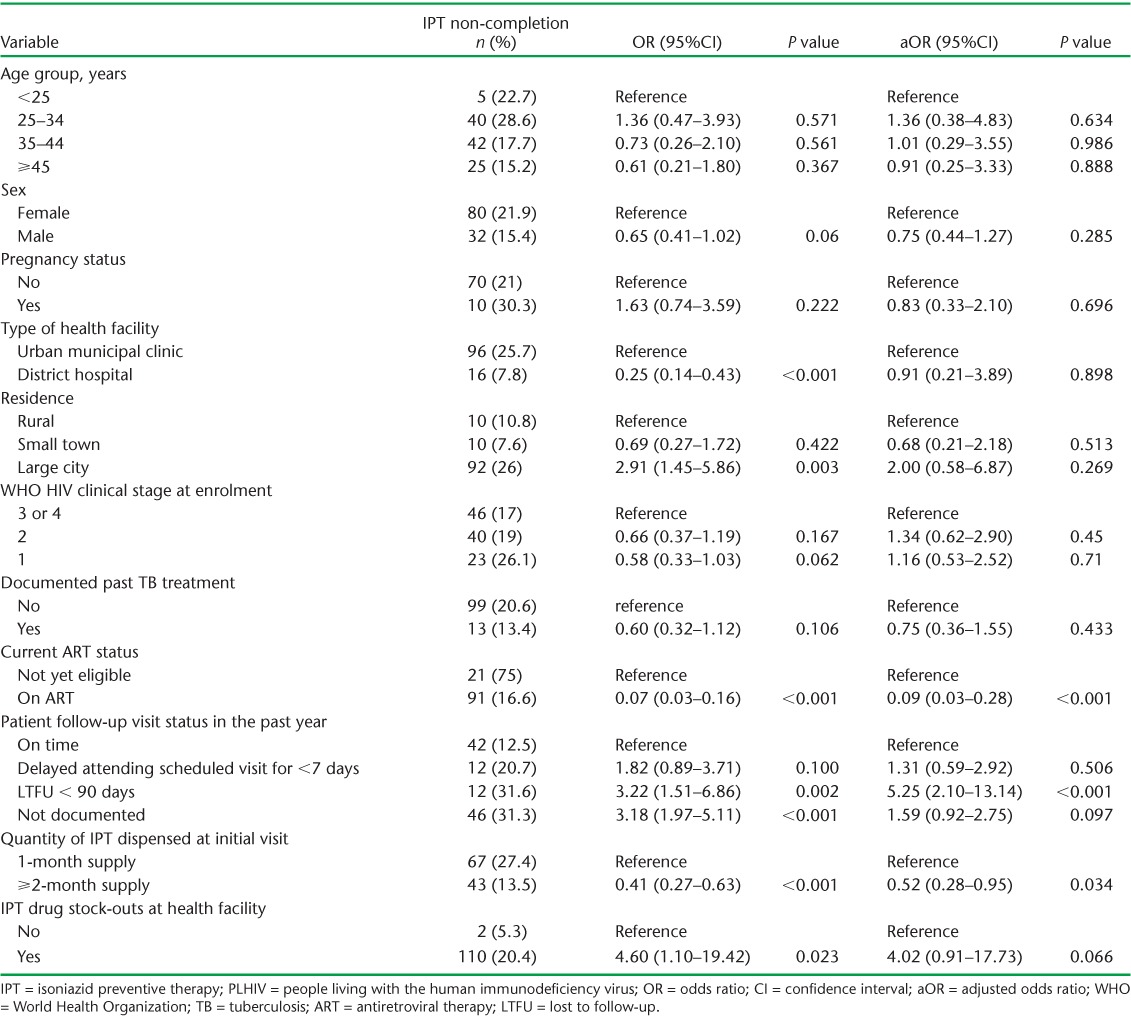

Risk factors associated with non-completion of isoniazid prevention therapy

The risk factors associated with IPT non-completion, after adjusting for other potential confounding variables, are shown in Table 4. Factors associated with a lower risk of IPT non-completion were currently being on ART (aOR 0.09, 95%CI 0.03–0.28) and receiving a ⩾2 month supply of INH at the start of the course. A history of missing clinic visits prior to starting IPT (aOR 5.25, 95%CI 2.10–13.14) was associated with a higher risk of IPT non-completion. IPT stock-outs recorded at the ART sites had a borderline association with IPT non-completion (aOR 4.02, 95%CI 0.91–17.73; P = 0.066).

TABLE 4.

Risk factors associated with IPT non-completion among PLHIV in Zimbabwe

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective cohort study, the completion of 6 months of IPT in PLHIV under routine conditions was comparatively high, at almost 80%, among PLHIV started on IPT during the first 2 months of the IPT roll-out pilot phase in Zimbabwe's public ART facilities. This completion rate is lower than those observed in eastern Kenya13 and Tanzania,14,15 but higher than in Uganda8 and Botswana.9 Among the patients who did not complete IPT, a large number were lost to follow-up, and many received only the first month's supply of IPT.

Although national indicators are collected monthly on ‘number on IPT’ and ‘number completing IPT’, there is currently no nationally agreed indicator to assess the IPT completion rate per cohort, and it is thus difficult to compare recorded completion rates against a set target. The task is not helped by the numerous paper-based registers at ART clinics, which health workers find difficult to use with the ever-increasing load of patients accessing and being retained on ART in the country. The recent adoption of a national electronic patient monitoring system (ePMS) in ART clinics countrywide might improve the situation, and may also help in the early identification and tracing of patients who are late for clinic visits or who have been lost to follow-up. The use of electronic medical record systems has been recommended for some time,16 and such systems have been shown to be useful for improving retention in ART care.17,18

While national IPT guidelines recommend that those initiated on IPT receive a 1-month supply of drugs during the initial visit,10 this practice was not common: nearly 60% of patients received ⩾2-month supplies of INH prophylaxis. Health workers explained that this was done in order to harmonise the supply of IPT drugs with the routine 2 or 3 month visits for antiretroviral drug (ARV) resupplies as, not surprisingly, patients prefer fewer visits to the health facilities. Fewer visits also reduces the patient workload for nurses at the ART clinics, which are already too high.19

While nearly a quarter of the patients who did not complete IPT had an undocumented reason for stopping treatment, almost all were currently active on ART and the reasons for stopping are unclear. One of the stated reasons for stopping was an adverse drug reaction. Adverse reactions are generally uncommon among PLHIV on IPT and can usually be safely managed.20 While some studies recommend the routine measurement of alanine aminotransferase levels with the subsequent interruption of IPT in those with elevated levels,21 laboratory monitoring is too difficult for most low-resource settings. Another reason for IPT non-completion was stock-outs of INH at the clinic, which highlights the challenges related to the supply chain management of IPT drugs. This is an area that requires improvement, as ARV drug stock-outs have been shown to be associated with non-adherence to ART and unplanned treatment interruption,22,23 and may also be a barrier to timely initiation of ART.24

In comparison with the PLHIV who attended review visits on time, those who had previously been lost to follow-up had higher odds of IPT non-completion. This underscores the need for health workers to provide enhanced adherence counselling on the benefits of IPT and ART for those PLHIV who have a history of interrupting treatment, to ensure IPT completion. Other factors associated with IPT completion included already being on ART and receiving a ⩾2-month supply of IPT drugs at the initial visit. We believe that these findings may be attributed to the synchronisation of IPT and ARV drug pick-up times and effective adherence support interventions. Patients who are not yet eligible for ART will generally not have undergone ART adherence counselling, and because they perceive themselves as well they may have irregular review visits, leading to IPT non-completion. Several studies support this supposition, showing high rates of loss to follow-up in pre-ART care in sub-Saharan Africa,25–27 and therefore a need for enhanced counselling on the benefits of IPT among these PLHIV.

The strengths of this study are the large, unbiased consecutive sample and the fact that it was conducted in the routine health system. The study limitations were mainly related to missing data due to the fact that this was a retrospective record review of routinely collected programme data.

The study has some important implications. First, as discussed earlier, it would be useful for the country's health decision makers to agree on indicators for IPT completion against which sites can compare their achievements. Second, an IPT register should be developed, similar to the district TB register, in which information on patients initiating IPT and on IPT pill pick-up visits could be recorded. This would enable cohort monitoring and routine tracing of patients who miss scheduled visits and are potentially at risk of not completing the full course of prophylactic treatment. Third, consideration should be given to linking the frequency of IPT review visits to the ART review visits to minimise disruption for patients who have to travel to the clinics to collect their drugs.

In conclusion, the IPT completion rate in the seven pilot sites was comparatively high, at 80%, showing that the roll-out of IPT in public health facilities in Zimbabwe is feasible and could be expanded countrywide. Patients who are not yet on ART, however, and those with a previous history of loss to follow-up, have a greater risk of IPT non-completion and require closer monitoring and enhanced counselling to ensure they complete treatment. Finally, it may be better to synchronise the supply of IPT drugs with ART resupplies at initiation, as this practice might be associated with lower rates of treatment non-completion. This initiative requires further implementation research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Ministry of Health and Child Welfare, Harare, Zimbabwe and its AIDS & TB Unit for their support and for granting permission to conduct the study.

Funding for the study was obtained from the World Health Organization Zimbabwe Country Office, while technical support was provided through the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union, Paris, France). The authors thank the Department for International Development (London, UK) for funding this open access publication and for funding the Global Operational Research Fellowship Programme at The Union, where KT works as an operational research fellow.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1. Lönnroth K, Jaramillo E, Williams B G, Dye C, Raviglione M.. Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: the role of risk factors and social determinants. Soc Sci Med 2009; 68: 2240– 2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. . Global tuberculosis report, 2016. WHO/HTM/TB/2016.13 Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. . Interim policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities. WHO/HTM/TB/2004.330 Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. . WHO policy on TB infection control in health-care facilities, congregate settings and households. WHO/HTM/TB/2009.419 Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. . Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grant A D, Charalambous S, Fielding K L, . et al. Effect of routine isoniazid preventive therapy on tuberculosis incidence among HIV-infected men in South Africa: a novel randomized incremental recruitment study. JAMA 2005; 293: 2719– 2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Golub J E, Saraceni V, Cavalcante S C, . et al. The impact of antiretroviral therapy and isoniazid preventive therapy on tuberculosis incidence in HIV-infected patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. AIDS 2007; 21: 1441– 1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Namuwenge P M, Mukonzo J K, Kiwanuka N, . et al. Loss to follow-up from isoniazid preventive therapy among adults attending HIV voluntary counselling and testing sites in Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2012; 106: 84– 89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. HIV and AIDS Treatment in Practice. . IPT for TB in people with HIV: barriers to national implementation. London, UK: National AIDS Manual, 2008. http://www.aidsmap.com/files/file1002936.pdf Accessed February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ministry of Health and Child Care. . Guidelines for the implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) for HIV-infected individuals during the feasibility phase of IPT in Zimbabwe, June–December 2012. Harare, Zimbabwe: MOHCC, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ministry of Health and Child Welfare. . Zimbabwe National Tuberculosis Control Programme manual. Harare, Zimbabwe: MOHCW, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Medicine and Therapeutics Policy Advisory Committee and AIDS and TB Directorate, Ministry of Health and Child Care. . Guidelines for antiretroviral therapy for the prevention and treatment of HIV in Zimbabwe, 2010. Harare, Zimbabwe: NMTPAC and MOHCC, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Masini E O, Sitienei J, Weyeinga H.. Outcomes of isoniazid prophylaxis among HIV-infected children attending routine HIV care in Kenya. Public Health Action 2013; 3: 204– 208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kabali C, von Reyn C F, Brooks D R, . et al. Completion of isoniazid preventive therapy and survival in HIV-infected, TST-positive adults in Tanzania. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013; 15: 1515– 1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Munseri P J, Talbot E A, Mtei L, Fordham von Reyn C.. Completion of isoniazid preventive therapy among HIV-infected patients in Tanzania. Int J Tu-berc Lung Dis 2008; 12: 1037– 1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harries A D, Zachariah R, Lawn S D, Rosen S.. Strategies to improve patient retention on antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2010; 15: 70– 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fraser H S, Allen C, Bailey C, Douglas G, Shin S, Blaya J.. Information systems for patient follow-up and chronic management of HIV and tuberculosis: a life-saving technology in resource-poor areas. J Med Internet Res 2007; 9: e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tweya H, Gareta D, Chagwera F, . et al. Early active follow-up of patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) who are lost to follow-up: the ‘Back-to-Care’ project in Lilongwe, Malawi. Trop Med Int Health 2010; 15: 82– 89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ministry of Health and Child Care. . 2012 ART annual report. Harare, Zimbabwe: MOHCC, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grant A D, Mngadi K T, van Halsema C L, Luttig M M, Fielding K L, Churchyard G J.. Adverse events with isoniazid preventive therapy: experience from a large trial. AIDS 2010; 24 ( Suppl 5): S29– S36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saukkonen J J, Cohn D L, Jasmer R M, . et al. An official ATS statement: hepatotoxicity of anti-tuberculosis therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174: 935– 952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boyer S, Clerc I, Bonono C R, Marcellin F, Bilé P C, Ventelou B.. Non-adherence to antiretroviral treatment and unplanned treatment interruption among people living with HIV/AIDS in Cameroon: individual and health-care supply-related factors. Soc Sci Med 2011; 72: 1383– 1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Uzochukwu B S, Onwujekwe O E, Onoka A C, Okoli C, Uguru N P, Chukwuogo O I.. Determinants of non-adherence to subsidized anti-retroviral treatment in southeast Nigeria. Health Policy Plan 2009; 24: 189– 196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muhamadi L, Nsabagasani X, Tumwesigye M N, . et al. Inadequate pre-antiretroviral care, stock-out of antiretroviral drugs and stigma: policy challenges/bottlenecks to the new WHO recommendations for earlier initiation of antiretroviral therapy (CD < 350 cells/microl) in eastern Uganda. Health Policy 2010; 97 ( Suppl 2–3): 187– 194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Amuron B, Namara G, Birungi J, . et al. Mortality and loss to follow-up during the pre-treatment period in an antiretroviral therapy programme under normal health service conditions in Uganda. BMC Public Health 2009; 9: 290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Larson B A, Brennan A, McNamara L, . et al. Early loss to follow up after enrolment in pre-ART care at a large public clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2010; 15: 43– 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rosen S, Fox M P.. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLOS Med 2011; 8: e1001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]