Abstract

Setting: Three public sector tertiary care hospitals in Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan, with anecdotal evidence of gaps between the diagnosis and treatment of patients with tuberculosis (TB).

Objectives: To assess the proportion of pre-treatment loss to follow-up (LTFU), defined as no documented evidence of treatment initiation or referral in TB registers, among smear-positive pulmonary TB patients diagnosed in 2015, and the associated sociodemographic factors.

Design: A retrospective cohort study involving the review of laboratory and TB registers.

Results: Of 1110 smear-positive TB patients diagnosed (58% female, median age 40 years, 5% from outside the province or the country), 235 (21.2%) were lost to follow-up before starting treatment. Pre-treatment LTFU was higher among males; in patients residing far away, in rural areas, outside the province or the country; and in those without a mobile phone number.

Conclusion: About one fifth of the smear-positive TB patients were lost to follow-up before starting treatment. Strengthening the referral and feedback mechanisms and using information technology to improve the tracing of patients is urgently required. Further qualitative research is needed to understand the reasons for pre-treatment LTFU from the patient's perspective.

Keywords: pre-treatment LTFU, initial LTFU, SORT IT, operational research

Abstract

Contexte : Trois hôpitaux publics tertiaires à Quetta, Baloutchistan, Pakistan, avec des preuves empiriques d'un fossé entre le diagnostic et le traitement des patients tuberculeux (TB).

Objectif : Evaluer la proportion de patients perdus de vue avant le traitement (pas de preuve documentée de mise en route du traitement ou de référence dans les registres TB) parmi les patients atteints de TB pulmonaire à frottis positif diagnostiqués en 2015, et identifier les facteurs sociodémographiques associés.

Schéma : Etude rétrospective de cohorte impliquant une revue des registres de laboratoire et de TB.

Résultats : Sur 1110 patients TB à frottis positif diagnostiqués (58% de femmes, d'âge médian 40 ans, 5% venant de l'extérieur de la province ou du pays), 235 (21,2%) ont été perdus de vue avant de démarrer le traitement. Cette perte de vue avant le traitement a été plus élevée parmi les hommes ; parmi les patients résidant loin, en zone rurale, hors de la province ou du pays ; et parmi ceux ne possédant pas de téléphone portable.

Conclusion : Environ un cinquième des patients TB à frottis positif ont été perdus de vue avant la mise en route du traitement. Il est nécessaire de manière urgente de renforcer les mécanismes de référence et de retro-information et d'avoir une meilleure traçabilité des patients grâce aux techniques d'information. Une autre recherche qualitative est requise afin de comprendre les raisons de cette perte de vue avant le traitement selon la perspective des patients.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: Tres hospitales de atención terciaria del sector público de Quetta, en la provincia de Balochistán del Pakistán, donde existen datos anecdóticos de un desfase entre el diagnóstico y el tratamiento de los pacientes con tuberculosis (TB).

Objetivos: Evaluar la proporción de pérdidas durante el seguimiento antes de comenzar el tratamiento (falta de documentación de la iniciación del tratamiento o la remisión a otros centros en los registros de TB) de los pacientes con TB pulmonar y baciloscopia positiva diagnosticados en el 2015 y analizar los factores socioeconómicos determinantes.

Métodos: Un estudio retrospectivo de cohortes a partir del examen de los registros de laboratorio y los registros de TB.

Resultados: De los 1110 pacientes con baciloscopia positiva diagnosticados (58% de sexo femenino, mediana de la edad 40 años y 5% procedente de otra provincia o país), 235 (21,2%) se perdieron durante el seguimiento antes de iniciar el tratamiento. Estas pérdidas fueron mayores en los pacientes de sexo masculino; los pacientes que residían en zonas rurales remotas, fuera de la provincia o del país; y en las personas que no contaban con un número de teléfono celular.

Conclusión: Cerca de un quinto de los pacientes con diagnóstico de TB y baciloscopia positiva se perdió durante el seguimiento antes de comenzar el tratamiento. Es urgente fortalecer el mecanismo de remisiones y de retroinformación de los resultados y mejorar la localización de los pacientes haciendo uso de la tecnología de la información. Se precisan nuevas investigaciones cualitativas que favorezcan la comprensión de las razones de esta pérdida durante el seguimiento desde la perspectiva de los pacientes.

Although it is a curable disease, tuberculosis (TB) remains a major global health problem and the leading cause of mortality due to an infectious disease, with an estimated 10.4 million notifications and 1.8 million deaths in 2015. Pakistan ranks fifth among the countries with the highest TB burden. According to the World Health Organization's 2016 global TB report, the estimated TB incidence in Pakistan in 2015 was 510 000 cases (270 per 100 000 population), of whom 331 809 were notified, yielding a treatment coverage rate of 63%.1

Approximately 4 million of the global estimated TB patients are missed from care, and Pakistan ranks third among the 12 countries that contribute 75% of missing TB cases,2,3 amounting to approximately 200 000 TB cases missed annually in the country.4 There are many reasons why cases are missed: patients residing in communities with limited access to health facilities, patients reaching the hospital but not diagnosed, patients diagnosed but not registered, and patients diagnosed and treated in the private sector but not notified to the national TB programme (NTP). One of these reasons is pre-treatment loss to follow-up (LTFU), defined as ‘any TB patient diagnosed but not initiated on treatment within a TB control programme setup’.5 Such patients, if untreated or mismanaged, are likely to die and/or develop drug resistance and continue to transmit the disease in the community.4,5 It is of great importance to address this issue from both patient and public health perspectives.

Previous studies from Pakistan and elsewhere have reported pre-treatment LTFU rates ranging from 5% to 25%.6–11 These studies had limitations in that they included only those patients who were residing within the district and focused mainly on primary health-care facilities. This is likely to underestimate the overall extent of the problem, as a large number of patients diagnosed in tertiary care hospitals are from outside the district, province or country, and the problem of pre-treatment LTFU is likely to be greater among these patients.

Balochistan, the largest province of Pakistan, occupying 44% of the country's territory (347 190 km2), contributes 5% of the total population and approximately 5% of the country's TB burden.20 As in other parts of the country, its tertiary care hospitals (TCHs) are the largest and best-equipped health facilities in the province. There is more potential for diagnosing smear-positive pulmonary TB patients in TCHs than in any other TB care facilities,4,12,13 and pre-treatment LTFU among this group is a serious public health problem. Due to weak, suboptimal health services at the peripheral levels in the province,20 the popularity of the TCHs and word-of-mouth referrals from previously treated patients, large numbers of patients from remote areas seek care at the TCHs situated in Quetta, the province's capital. Programmatic data from 2015 show that the three public sector TCHs contributed 26% of all TB cases notified to the provincial TB control programme. These data suggest that gaps exist between the number of patients diagnosed with TB and the number initiated on treatment.

The aim of this study was to assess the magnitude of pre-treatment LTFU among smear-positive pulmonary TB patients diagnosed in public sector TCHs and to identify associated sociodemographic factors.

METHODS

Design

This was a retrospective cohort study involving the review of routinely maintained programme records.

Setting

The study was conducted in Quetta, the capital city of Balochistan (population 9.6 million),14 located in the north-western part of the province near the Afghanistan border. The study was carried out in three of the five public sector TCHs (Fatima Jinnah Chest and General Hospital, Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Hospital and Bolan Medical Complex Hospital) that manage TB patients according to the NTP guidelines. The period of data review was January–December 2015. Data collection was undertaken from May to August 2016.

In the TCHs, presumptive TB patients are identified at the out-patient department based on their symptoms and sent to the laboratory for sputum smear examination using conventional light and/or fluorescence microscopy.4 Two specimens are collected from the presumptive TB patient: a spot specimen on day 1 and a second early-morning specimen on day 2. Microscopy is performed on both samples by a trained laboratory technician on day 2 and the results are shared with the patient before the close of business on day 2. The results are recorded in a laboratory register (TB-04), and patients identified as smear-positive are referred back to the treating physician and/or TB DOTS focal point (a unit in the hospital managing TB patients) for treatment initiation and recording in the TB register (TB-03). Patients who do not return to collect the results, especially those diagnosed with smear-positive TB, are contacted by telephone, wherever available. The TCHs are linked to all of the TB care facilities of the province for pre-registration referral and transfer out of TB patients coming from other districts. Before registration, patients are offered a referral service by trained staff so that they can receive treatment in their home district, town or nearby facility.12 Referred patients are provided with treatment doses for 1 week and a standard referral form with the contact details of the health centre (address and phone number), and are instructed to attend the centre to continue treatment. The referral form has two parts: the first, maintained at the health centre, is attached to the treatment card of the patient, and the second is shared with the monitoring officer of the NTP, who in turn facilitates the transmission of feedback to the TCHs.

Study population

The study population included all the smear-positive pulmonary TB patients aged >5 years diagnosed in 2015 by conventional light and/or fluorescence microscopy, regardless of sex and address, at the three TCHs participating in the study.

For study purposes, we defined ‘pre-treatment LTFU’ as any smear-positive TB patient who was diagnosed (as documented in register TB-04) but who had no documented evidence of treatment initiation (register TB-03) or referral by the censor date (31 January 2016). To assess treatment initiation, we first checked the TB-03 register and the referral for TB register maintained in the hospital. If the patient was missing from this register, we checked the treatment register of the other TB care facilities of the district and province using the patient's name, age and sex. If the patient was found in these treatment registers, he/she was considered to have started treatment. If not, he/she was classified as ‘pre-treatment LTFU’. Patients who were referred out for treatment but who had no documented evidence of starting treatment in the destination TB care facility were also classified as pre-treatment LTFU.

Data collection and validation

The data were sourced from the TB laboratory registers (TB-04) and the TB registers (TB-03). Data were collected using a pre-structured data collection tool from May to August 2016. The outcome variable was ‘pre-treatment LTFU’, as defined above. Additional information collected, including TB number, patient name, sex and age, were used for tracing the patients' details in the TB treatment register. The distance of the patient's residence from the health facility was measured using Google Maps (Google Inc, Mountain View, CA, USA). Travel time was estimated by the principal investigator working in the provincial TB control programme, who was familiar with the setting.

Analyses and statistics

Data were double entered, validated and analysed using EpiData software (v. 3.1 for entry and v. 2.2.2.183 for analyses, EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study population. Categorical variables were summarised in terms of frequencies and proportions, and continuous variables were summarised in terms of mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (interquartile range [IQR]), as appropriate. Proportions and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to describe the magnitude of pre-treatment LTFU.

Factors associated with pre-treatment LTFU were determined using the χ2 test and relative risk with 95%CI. Levels of significance were set at 5%.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France. Permission to use the data and local ethics exemption were obtained from the programme manager of the provincial TB control programme. As the study involved a review of records with no patient interaction, the need for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee.

RESULTS

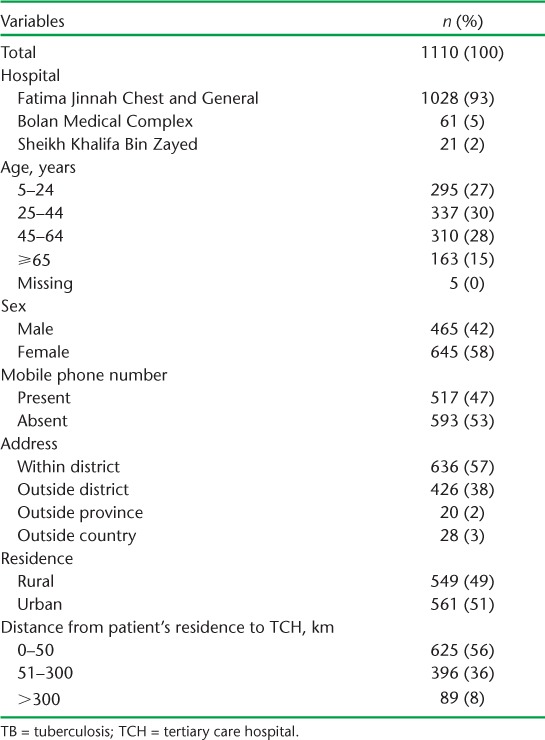

A total of 1110 smear-positive pulmonary TB patients were diagnosed during the study period. The basic sociodemographic characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Of these patients, 93% were diagnosed in Fatima Jinnah Hospital and 58% were females. The median age was 40 years (IQR 25–60) and only 2% of the patients were children (aged <15 years). While about half of the patients lived in urban areas and within the district, the rest came from rural areas and frequently out of the district. Some (2%) came from the neighbouring provinces (Sindh and Punjab), and about 3% came from neighbouring Afghanistan. The median distance of the patient's residence from the hospital was 6 km (IQR 3–125); and the median time for travel by road was 0.5 h (IQR 0.3–2.0). A little over half of the patients had no access to a mobile phone.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of smear-positive pulmonary TB patients diagnosed in three TCHs in Quetta, Pakistan, 2015

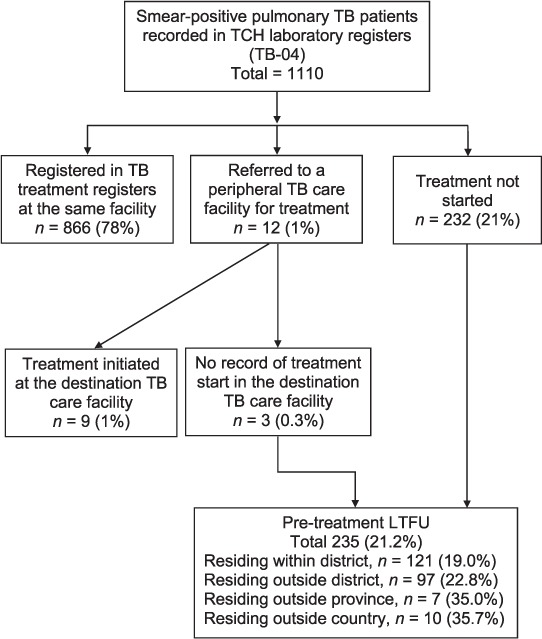

Among the 1110 patients diagnosed, 866 (78%) were documented to have started on treatment in the same facility and 12 were documented to have been referred out to another health facility, of whom 9 were started on treatment. A total of 235 (21.2%) patients had no documentation of treatment initiation or referral and were considered as pre-treatment LTFU (Figure). Among those started on treatment, the median duration between diagnosis and treatment initiation was 1 day (IQR 0–3).

FIGURE.

Flow diagrams of pre-treatment LTFU of smear-positive pulmonary TB patients in tertiary care hospitals, Quetta, Pakistan, 2015. TB = tuberculosis; TCH = tertiary care hospital; LTFU = loss to follow-up.

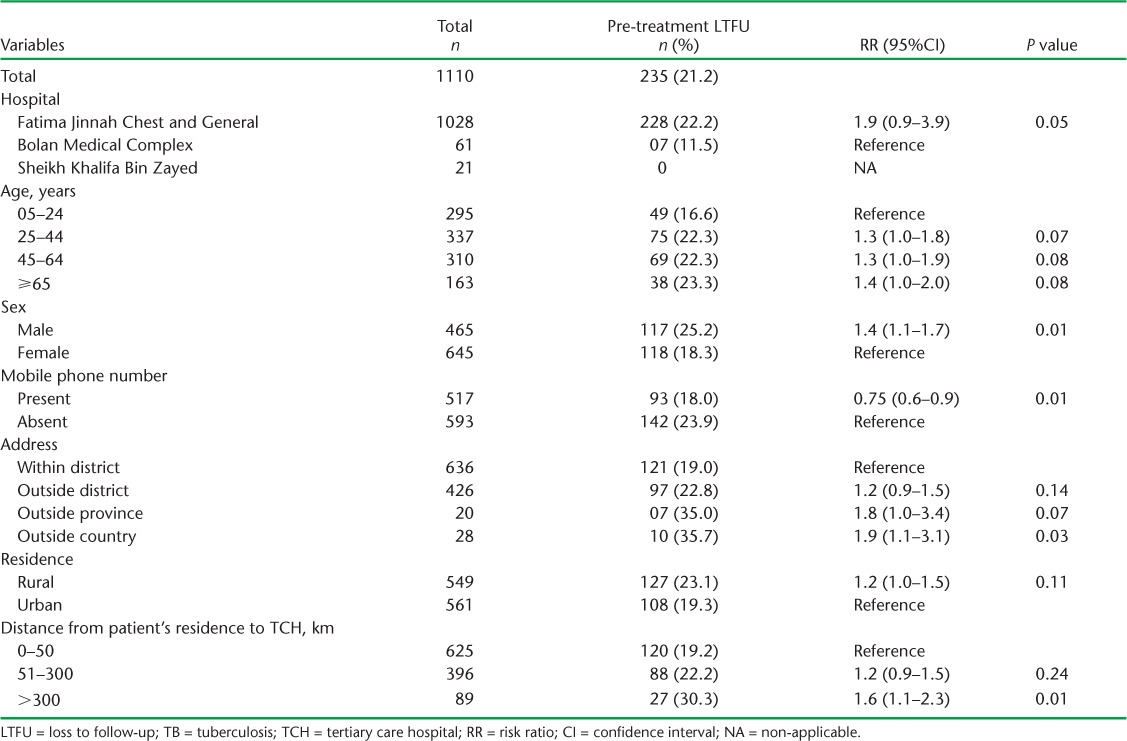

Table 2 shows the factors associated with pre-treatment LTFU, which was highest in Fatima Jinnah Hospital followed by Bolan Hospital. There was no pre-treatment LTFU in Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Hospital. Pre-treatment LTFU was associated with male sex, rural residence, residence outside the province or country, lack of access to a mobile phone and distance from the residence to the hospital.

TABLE 2.

Factors associated with pre-treatment LTFU among smear-positive pulmonary TB patients in three TCHs in Quetta, Pakistan, 2015

DISCUSSION

About one fifth of the infectious, bacteriologically confirmed, smear-positive pulmonary TB patients diagnosed in the TCHs of Quetta, Balochistan, were lost to follow-up before starting treatment. This is higher than the rate of 10% reported in a previous study from Pakistan.11 This could be attributed to the tertiary care setting in which we conducted the study, and the fact that we included all patients, including those residing outside the district, province or country.

The study has several strengths. First, it had a large sample size and covered the largest THCs of Quetta. Second, as it used routinely collected data, the findings reflect programmatic reality. Third, we adhered to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines, including those for ethical considerations, for this study.17

The limitations of the study include the fact that we relied on a review of programme records to assess pre-treatment LTFU and did not actively trace patients. Furthermore, it was not feasible to review the treatment registers of facilities situated outside the province and country. It is therefore possible that some TB patients might have been started on treatment elsewhere, outside the province/country, yet classified as ‘pre-treatment LTFU’. As, however, these patients represent only 5% of all patients in the study, this factor is unlikely to have much bearing on the overall results. The other limitation is that we did not ascertain the exact reason for pre-treatment LTFU from the patient's perspective. This requires future study using qualitative research methods.

Based on our programme experience, we can, however, speculate as to the possible reasons for pre-treatment LTFU. The high rate of pre-treatment LTFU in the TCHs might be due to poor interdepartmental coordination, especially between the laboratory and the treatment focal points.7 Other reasons could be inadequate counselling of identified presumptive TB patients by the laboratory technicians due to high workload; weaknesses in the pre-registration referral and feedback mechanisms;12 and the non-use of technology for real-time tracing of patients. Another possibility is that some patients might be receiving treatment in the private sector without being notified to the NTP.

We identified several programmatically relevant factors associated with pre-treatment LTFU. One was the distance from the patient's residence to the TCH—the further the distance, the higher the rate of pre-treatment LTFU, especially for patients living outside the province or the country or living in rural areas. Having a mobile phone number was associated with a lower risk of initial LTFU, indicating that patients were more easily traced when their mobile phone number was properly recorded in the laboratory registers.

The results of this study have a number of implications for the NTP. First, pre-treatment LTFU is a major problem for TB control programmes, particularly when patients choose to seek care in the private health sector, where there is frequently no notification, quality control or treatment evaluation.18 Strategies are urgently needed to improve the registration of all identified smear-positive TB patients at the same facility or to improve notification from the private sector. Second, the recording of certain fields in the laboratory registers, such as detailed addresses, telephone numbers and TB registration numbers, needs improvement. This will assist efforts in tracing and retrieval of pre-treatment LTFU TB patients. Third, the internal hospital coordination mechanisms and external linkage of the hospital to refer patients to peripheral TB care facilities need to be strengthened.13 Fourth, the NTP's quarterly reports should include the number of pre-treatment LTFU smear-positive TB patients to improve the monitoring of both case finding and treatment results.5 Fifth, we need both to strengthen the routine comparison of the laboratory and TB treatment registers in each facility and to consider linking the laboratory register electronically to the treatment register at facility and district levels, which would enable real-time tracing of patients. Finally, the quality of TB services at primary health centres should be improved to increase their utilisation by patients.11,12,19

CONCLUSION

In the TCHs of Quetta, Pakistan, the proportion of pre-treatment LTFU was very high. Strategies are urgently needed to improve the registration of these highly infectious patients on treatment to stop the further spread of TB in the community.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization (WHO/TDR). The training model is based on a course developed jointly by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union, Paris, France) and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, Geneva, Switzerland).

The authors gratefully acknowledge the cooperation and facilitation from the provincial TB control programme of Balochistan. We are grateful to M Khan (student, City School, Quetta, Pakistan), I Ahmed (TB Control Programme, Balochistan) and Z Ahmad (TB Control Programme, Balochistan) for facilitating the data entry. The specific SORT IT programme that resulted in this publication was implemented by the National Tuberculosis Control Programme of Pakistan, through the support of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (The Global Fund, Geneva, Switzerland), WHO-TDR, the University of Bergen (Bergen, Norway), The Union, and The Union South-East Asia Office (New Delhi, India). The programme was funded by the WHO and the Global Fund in Pakistan. The publication fees were covered by the WHO/TDR. In accordance with the WHO's open-access publication policy for all work funded by the WHO or authored/co-authored by WHO staff members, the WHO retains the copyright of this publication through a Creative Commons Attribution IGO license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/legalcode) that permits the unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly cited.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. . Global tuberculosis report, 2016. WHO/HTM/TB/2016.13 Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. . TB: Reach the 3 Million. Find. Treat. Cure. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. . Global tuberculosis report, 2013. WHO/HTM/TB/2013.11 Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ministry of National Health Services. . National guidelines for the management of tuberculosis in Pakistan. Islamabad, Pakistan: Ministry of National Health Services, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. MacPherson P, Houben R M G J, Glynn J R, Corbett E L, Kranzer K.. Pre-treatment loss to follow-up in tuberculosis patients in low- and lower-middle-income countries and high-burden countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2014; 92: 126– 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fatima R, Qadeer E, Hinderaker S G, . et al. Can the number of patients with presumptive tuberculosis lost in the general health services in Pakistan be reduced? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015; 19: 654– 656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ram S, Kishore K, Batio I, . et al. Pre-treatment loss to follow-up among smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis cases: a 10-year audit of national data from Fiji. Public Health Action 2012; 2: 138– 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Afutu F K, Zachariah R, Hinderaker S G, . et al. High initial default in patients with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis at a regional hospital in Accra, Ghana. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2012; 106: 511– 513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Botha E, Den Boon S, Lawrence K A, . et al. From suspect to patient: tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment initiation in health facilities in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008; 12: 936– 941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Claassens M M, Du Toit E, Dunbar R, . et al. Tuberculosis patients in primary care do not start treatment. What role do health system delays play? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2013; 17: 603– 607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fatima R, Ejaz Q, Enarson D A, Bissell K.. Comprehensiveness of primary services in the care of infectious tuberculosis patients in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Public Health Action 2011; 1: 13– 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sven G H, Fatima R.. Lost in time and space: outcome of patients transferred out from large hospitals. Public Health Action 2013; 3: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anila B, Mazher A K, Dost M, . et al. Need for establishing a linkage between tertiary care hospitals and peripheral DOTS centers. Pakistan J Chest Med 2013; 19: 3. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Balochistan Population Welfare Department. . Population Welfare. Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan: Population Welfare Department, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Buu T N, Lönnroth K, Quy H T.. Initial defaulting in the National Tuberculosis Programme in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: a survey of extent, reasons and alternative actions taken following default. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2003; 7: 735– 741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harries A D, Rusen I D, Chiang C Y, Hinderaker S G, Enarson D A.. Registering initial defaulters and reporting on their treatment outcomes. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009; 13: 801– 803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M, . et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting of observational studies. Internist 2008; 49: 688– 693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Soomro M H, Qadeer E, Mørkve O.. Barriers in the management of tuberculosis in Rawalpindi, Pakistan: a qualitative study. Tanaffos 2013; 12: 28– 34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jha U M, Satyanarayana S, Dewan P K, . et al. Risk factors for treatment default among re-treatment tuberculosis patients in India, 2006. PLOS ONE 2010; 5: 2– 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National TB Control Programme Pakistan. . National TB Control National Plan ‘Vision 2020.’ Islamabad, Pakistan: Ministry of National Health Services, 2014. [Google Scholar]