Abstract

Objectives

To describe the disposition of young children diagnosed with physical abuse in the emergency department (ED) setting and identify factors associated with the decision to discharge young abused children.

Study design

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional study of children less than 2 years diagnosed with physical abuse in the 2006-2012 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample. National estimates were calculated accounting for the complex survey design. We developed a multivariable logistic regression model to evaluate the relationship between payer type and discharge from the ED compared with admission with adjustment for patient and hospital factors.

Results

Of the 37,655 ED encounters with a diagnosis of physical abuse among children less than 2 years, 51.8% resulted in discharge, 41.2% in admission, 4.3% in transfer, 0.3% in death in the ED, and 2.5% in other. After adjustment for age, sex, injury type, and hospital characteristics (trauma designation, volume of young children, and hospital region), there were differences in discharge decisions by payer and injury severity. The adjusted percentage discharged of publicly insured children with minor/moderate injury severity was 56.2% (95% CI 51.6, 60.7). The adjusted percentages discharged were higher for both privately insured children at 69.9% (95% CI 64.4, 75.5) and self-pay children at 72.9% (95% CI 67.4, 78.4). The adjusted percentages discharged among severely injured children did not differ significantly by payer.

Conclusions

The majority of ED visits for young children diagnosed with abuse resulted in discharge. The notable differences in disposition by payer warrant further investigation.

Keywords: Child Abuse, Emergency Medicine, Healthcare Disparities

In an era of increasingly cost-conscious medical practice, type of health insurance has emerged as a factor associated with disparities in disposition decisions in cases of trauma1-3 and in children with cancer.4 However, less is known about how the association between insurance type and disposition extends to the vulnerable population of young abused children. Children younger than 2 years of age account for approximately one-fifth of cases of child maltreatment and over 60% of child fatalities from abuse.5 Emergency medicine physicians must not only screen for and diagnose physical abuse among these young patients, but must also work in consultation with child protective services to determine a safe disposition for the abused child, who may require hospital admission for treatment of injuries, for further evaluation, or to ensure safety.6 Socioeconomic status (SES)-based disparities have been observed in the decision to screen for and diagnose physical abuse,7-12 but the impact of SES on disposition decisions has not been evaluated.

This study aimed to describe the frequency and characteristics of ED visits for children younger than 2 years with physical abuse by disposition and identify factors associated with the decision to discharge these children from the ED. Because a family’s SES may contribute to the provider’s assessment of a child’s safety, we hypothesized that biases could exist in disposition decisions in cases of child abuse, with public insurance status decreasing the odds of discharge after adjustment for patient and hospital-level factors.

METHODS

We derived our cohort using the 2006-2012 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS), a Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) dataset comprised of more than 950 unique hospital-based EDs in the United States that allows for weighted national estimates.13 We used the recently corrected version of the 2011 NEDS.14 The NEDS is also the largest publicly available ED dataset in the United States that includes all payers13 and has been used for multiple studies of child abuse.15, 16 This dataset includes up to 15 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes with each ED encounter, as well as patient and hospital characteristics described below. As the NEDS lacks patient identifiers, we could not determine if ED visits represented unique patients. This de-identified administrative data was exempt from review by our institutional review board.

The study population was ED encounters of children less than 2 years with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of abuse (995.50, 995.54, 995.55, 995.59) and/or an external injury cause code (E-code) of assault or perpetrator of abuse (E960.0, E961, E963-E967; E968.0-E968.3; E968.5-E968.9). We excluded children with E-codes for transportation accidents (E800-E848) and children with billing codes for a late effect of injury (905-909, E969). There is no validated approach to specifically identify physical abuse in the emergency setting through billing codes. We chose to include the nonspecific codes of 995.50 (Child Abuse, Unspecified) and 995.59 (Other Child Abuse and Neglect), as these codes have been used in a validated inpatient algorithm with a high specificity for physical abuse.17 Because we elected to not require an injury diagnosis code, we evaluated whether these more general codes (995.50 and 995.59) contributed a large proportion of uninjured children to our cohort.

Study Outcome and Exposures

The primary outcome of interest was discharge from the ED, defined as routine discharge or discharge to home health care. We described patient and hospital characteristics of these discharges from the ED and admissions to the same hospital. We report the percentages of children transferred to short-term hospitals and those who died in the ED. The few remaining encounters with unknown or ill-defined dispositions were grouped as “other.”

Patient characteristics included age (available only in years), sex, insurance type, median household income quartile of the patient’s ZIP Code, injury type defined by ICD-9-CM codes, and Injury Severity Score (ISS). The ISS, which ranges from 0 to 75, is derived from the sum of the squares of the Maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale (MAIS) scores of the 3 most severely injured body regions. MAIS scores range from 1 to 6 and were calculated using a two-step process. First, an investigator certified in Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) scoring (MRZ) mapped each ICD-9-CM code associated with the visit to the 1998 version of the AIS (AIS98) codes using the ICDMAP-90 software,18 then manually re-mapped codes to the most recent AIS 2005/2008 versions using the AIS manual and the ICD-9-CM injury descriptions.18-20 This remapping was necessary to ensure the severities from the most recent manual were used. Due to the small proportion of children with an ISS ≥15, ISS was collapsed into the following categories for modeling: no injury (0 or incalculable), minor/moderate injury (1-4) and severe injury (≥5).

We also reported hospital characteristics such as urban vs. rural location, trauma center status, geographic region, and teaching status. In order to account for each hospital’s familiarity with the care of young children, we calculated the average annual percentage of total ED volume comprised of children less than 2 years of age for all hospitals that contributed data to the NEDS. We stratified this hospital percentage at the 25th and 75th percentiles to produce 3 levels of ED volume of children less than 2 years (low, medium, and high).

Data Analyses

All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata 13.1 (College Station, TX). Weighted statistical techniques were utilized to produce national event-level estimates with the NEDS hospital stratum as the stratification unit and the ED event as the unit of analysis. We described disposition by patient and hospital-level characteristics.

We developed a multivariable logistic regression model identifying patient and hospital-level factors associated with discharge from the ED. We focused exclusively on children who were discharged from the ED or admitted to the same hospital, as too few patients were transferred for stable modeling. Our main exposure of interest was insurance type, which would reasonably be associated with the individual child’s SES. We considered age, sex, national quartile for median household income of the child’s ZIP Code, urban vs. rural hospital, ISS, hospital region, trauma center status, teaching status, injury type (fracture, intracranial, abdominal, open wound, contusion/superficial injury, other), and hospital volume of young children. We elected to use insurance type as a primary exposure in lieu of national quartile for median household income of the child’s ZIP Code. Insurance type was preferable because it is a patient-specific proxy measure of SES. National quartile for median household income of the subject’s ZIP Code potentially represents a heterogeneous population and may not accurately reflect the SES of an individual family. Urban center and teaching status were excluded from our final model because the vast majority of trauma centers are teaching hospitals in urban locations. We evaluated for effect modification between ISS and payer and calculated the adjusted probability of discharge (expressed as a percentage) for each payer and ISS category. This marginal estimate allowed us to examine the percentage discharged within each payer and ISS category with the benefit of adjustment for all other covariates in our final model, accounting for the survey design.21 Statistical significance was defined by P < 0.05.

RESULTS

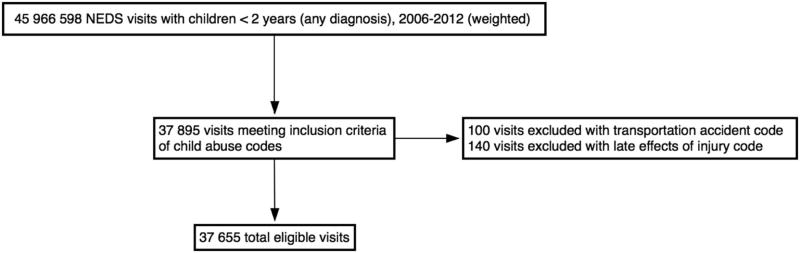

Between 2006 and 2012, a weighted total of 37,655 ED visits of children less than 2 years of age were associated with a diagnosis of physical abuse meeting our inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1; available at www.jpeds.com). In this cohort of visits, 51.8% (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 48.0, 55.7) resulted in discharge, and 41.2% (95% CI: 36.8, 45.6) ended in admission. Only 4.3% (95% CI: 3.5, 5.0) were transferred, and 0.3% (95% CI: 0.1, 0.4) died while in the ED. The remaining 2.5% (95% CI: 1.8, 3.1) had other dispositions.

FIGURE 1.

Study Population Flow Diagram

Admitted children were generally younger compared with children who were discharged. We found that 49.9% of discharged children were less than 1 year of age compared with 77.3% of admitted children (Table I). Children with public insurance comprised 70.3% of the entire abused cohort. A total of 64.4% discharged children and 78.8% of admitted children had public insurance. The majority of discharged children were less severely injured with an ISS between 1 and 4 (58.4%). Admitted children were generally more severely injured, with a predominance of admitted children (63.8%) having an ISS of 5 or higher.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Physically Abused Young Children in US Emergency Departments*

| All Dispositions N = 37,655 | Discharged N = 19,519 | Admitted N = 15,510 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Column % (95% CI) | Column % (95% CI) | Column % (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <1 | 23,434 | 62.2 (60.4, 64.1) | 49.9 (48.3, 51.6) | 77.3 (75.7, 79.0) |

| ≥1 | 14,220 | 37.8 (35.9, 39.5) | 50.1 (48.4, 51.7) | 22.7 (21.0, 24.3) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 20,531 | 54.6 (53.4, 55.8) | 50.9 (49.3, 52.5) | 58.9 (57.0, 60.8) |

| Female | 17,085 | 45.4 (44.2, 46.6) | 49.1 (47.5, 50.7) | 41.1 (39.2, 43.0) |

| Median household income quartile of ZIP Code | ||||

| 1 (Lowest) | 14,555 | 38.7 (36.5, 40.8) | 40.9 (38.2, 43.5) | 35.6 (32.9, 38.3) |

| 2 | 11,030 | 29.3 (27.7, 30.9) | 30.2 (28.0, 32.3) | 28.7 (26.8, 30.7) |

| 3 | 7,118 | 18.9 (17.6, 20.2) | 17.6 (16.1, 19.2) | 20.2 (18.2, 22.2) |

| 4 (Highest) | 4,030 | 10.7 (9.4, 12.0) | 9.3 (8.1, 10.6) | 12.4 (10.4, 14.4) |

| Payer | ||||

| Private | 6,234 | 16.6 (15.0, 18.1) | 18.9 (17.1, 20.8) | 13.6 (11.4, 15.8) |

| Public | 26,456 | 70.3 (68.3, 72.2) | 64.4 (62.1, 66.7) | 78.8 (76.2, 81.3) |

| Self | 3,444 | 9.1 (8.0, 10.3) | 12.9 (11.3, 14.4) | 3.3 (2.5, 4.1) |

| Other/Unknown | 1,520 | 4.0 (3.3, 4.7) | 3.8 (3.0, 4.6) | 4.3 (3.1, 5.5) |

| Injury Severity Score | ||||

| 0 or incalculable | 10,103 | 26.8 (24.8, 28.8) | 38.5 (36.4, 40.5) | 11.6 (10.1 13.2) |

| 1-4 | 16,281 | 43.2 (41.1, 45.4) | 58.4 (56.4, 60.4) | 24.6 (22.1, 27.1) |

| 5-14 | 9,650 | 25.6 (22.8, 28.5) | 3.1 (2.3, 3.9) | 53.7 (51.0, 56.4) |

| ≥15 | 1,620 | 4.3 (3.5, 5.1) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) | 10.1 (8.6, 11.6) |

| Type of Injury# | ||||

| No injury codes | 7,166 | 19.0 (17.4, 20.7) | 26.2 (24.1, 28.4) | 10.1 (8.7, 11.6) |

| Any fracture | 9,830 | 26.1 (23.6, 28.6) | 5.3 (4.3, 6.3) | 52.5 (50.5, 54.4) |

| Intracranial injury | 6,868 | 18.2 (16.0, 20.5) | 1.5 (1.1, 1.9) | 39.5 (36.3, 42.8) |

| Burn | 1,309 | 3.5 (2.9, 4.0) | 2.8 (2.2, 3.3) | 4.0 (3.0, 5.0) |

| Open Wound | 3,039 | 8.1 (7.4, 8.8) | 10.2 (9.2, 11.3) | 5.7 (4.6, 6.8) |

| Contusion/superficial injury | 14,910 | 39.6 (38.1, 41.1) | 46.5 (44.6, 48.4) | 31.4 (29.4, 33.5) |

| Abdominal injury | 850 | 2.3 (1.8, 2.7) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) | 5.2 (4.4, 6.0) |

| Other injury | 5,159 | 13.7 (12.7, 14.7) | 17.1 (15.7, 18.5) | 8.6 (7.4, 9.8) |

Percentages, row, and column totals may not sum to the total or 100% due to rounding, missing data, and because transfers, deaths in the emergency department, and other dispositions are not represented.

One patient may have multiple injuries and be represented more than once in the Type of Injury section.

Injuries of Abused Children by Disposition

The most common injuries among discharged children were contusions and superficial injuries (46.5%) (Table I). Conversely, the most common injury type among admitted children was fracture (52.5%), followed by intracranial injury (39.5%).

Nineteen percent of the overall cohort did not have an associated injury ICD-9-CM diagnosis code within the 800 to 959 range. The addition of codes outside this traditional range that could be associated with injury (such as retinal hemorrhages) did not significantly lower this percentage. More children lacked an injury code in the discharged group (26.2%) compared with the admitted group (10.1%). Next we explored whether our inclusion of the nonspecific child abuse ICD-9-CM codes (995.50 and 995.59) was responsible for the addition of many children into the overall cohort and whether these codes disproportionally accounted for the 19.0% of abused children without injury codes. Only 5.2% of ED encounters entered the overall cohort due to a sole ICD-9-CM code of 995.50 or 995.59. A total of 2.6% of the overall cohort was comprised of uninjured children with a sole ICD-9-CM code of 995.50 or 995.59.

Hospital Characteristics by Disposition

The majority of the cohort (82.0%) presented to urban hospitals (Table II). Hospital encounters from the Midwest (29.0%) and South (34.8%) comprised the largest proportion of the cohort. A total of 49.2% children who were discharged and 83.9% of those admitted presented to a trauma center. Although 89.1% of admitted children presented to a metropolitan teaching hospital, only 54.2% of discharged children presented to a metropolitan teaching hospital.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Emergency Departments by Disposition

| All Dispositions N = 37,655 | Discharged N = 19,519 | Admitted N = 15,510 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Column % (95% CI) | Column % (95% CI) | Column % (95% CI) | |

| Trauma Center | ||||

| No | 14,086 | 37.4 (32.6, 42.2) | 50.8 (46.1, 55.5) | 16.1 (10.6, 21.7) |

| Yes | 23,569 | 62.6 (57.8, 67.4) | 49.2 (44.5, 53.9) | 83.9 (78.3, 89.4) |

| Hospital Region | ||||

| Northeast | 6,262 | 16.6 (13.5, 19.7) | 19.6 (16.4, 22.8) | 13.5 (8.9, 18.0) |

| Midwest | 10,933 | 29.0 (22.7, 35.3) | 27.4 (22.1, 32.6) | 30.4 (19.8, 41.1) |

| South | 13,114 | 34.8 (29.6, 40.1) | 37.0 (32.8, 41.2) | 31.8 (22.9, 40.6) |

| West | 7,345 | 19.5 (14.8, 24.2) | 16.1 (13.5, 18.7) | 24.3 (15.2, 33.4) |

| Urban | ||||

| Urban | 30,865 | 82.0(80.2, 83.8) | 80.3 (78.2, 82.3) | 85.4 (82.4, 88.3) |

| Rural | 6,638 | 17.6 (15.9, 19.4) | 19.4 (17.4, 21.5) | 14.2 (11.3, 17.1) |

| Teaching Hospital | ||||

| Metropolitan non-teaching | 7,804 | 20.7 (17.5, 23.9) | 28.1 (24.8, 31.5) | 8.6 (5.4, 11.8) |

| Metropolitan teaching | 25,430 | 67.5 (63.3, 71.7) | 54.2 (49.8, 58.6) | 89.1 (85.6, 92.6) |

| Non-metropolitan* | 4,420 | 11.7 (10.0, 13.5) | 17.7 (15.4, 19.9) | 2.3 (1.5, 3.1) |

| Volume of children < 2# | ||||

| Low | 2,961 | 7.9 (6.1, 9.7) | 11.0 (8.5, 13.5) | 2.6 (1.4, 3.8) |

| Medium | 10,390 | 27.6 (23.4, 31.8) | 35.6 (31.4, 39.8) | 14.5 (9.8, 19.2) |

| High | 24,303 | 64.5 (59.5, 69.6) | 53.4 (48.4, 58.4) | 82.9 (77.7, 88.0) |

The NEDS does not stratify non-metropolitan hospitals by teaching status.

ED volume of children <2 was calculated using all hospitals in the NEDS. Because not all hospitals evaluated children for abuse, the distribution of this categorical variable in our study cohort does not equal low (25%), medium (50%), high (25%).

Factors Associated with Discharge

Controlling for age, sex, payer status, ISS category, hospital trauma center status, ED volume of children less than 2 years old, injury type, hospital region, and the interaction between payer status and ISS category, we calculated the adjusted odds of discharge (Table III). We found that one-year-old children were more likely to be discharged than those less than 1 year of age (OR 2.01; 95% CI 1.74, 2.33). Females were more likely to be discharged than males (OR 1.20; 95% CI 1.04, 1.39). Children who received care at a trauma center were less likely to be discharged (OR 0.30; 95% CI 0.22, 0.41). Children presenting to hospitals with patient populations composed of a high proportion of young children were less likely to be discharged than those with a low proportion of young children (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.25, 0.62). Children with fractures (OR 0.13; 95% CI 0.09, 0.19), intracranial injuries (OR 0.08; 95% CI 0.05, 0.12), abdominal injuries (OR 0.02; 95% CI 0.01, 0.07), and burns (OR 0.23; 95% CI 0.16, 0.35) were less likely to be discharged. Children with other injuries were more likely to be discharged (OR 1.90; 95% CI 1.50, 2.42).

TABLE 3.

Factors Associated with Discharge (versus Admission) from the Emergency Department*

| OR | 95% CI | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Factors | |||

| Age | |||

| < 1 year | Ref. | — | |

| ≥1 year | 2.01 | 1.74, 2.33 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | Ref. | — | |

| Female | 1.20 | 1.04, 1.39 | 0.01 |

| Injury Type§ | |||

| Fracture | 0.13 | 0.09, 0.19 | < 0.001 |

| Intracranial Injury | 0.08 | 0.05, 0.12 | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal Injury | 0.02 | 0.01, 0.07 | < 0.001 |

| Contusion/superficial Injury | 1.07 | 0.82, 1.39 | 0.62 |

| Open Wound | 0.91 | 0.67, 1.24 | 0.55 |

| Burn | 0.23 | 0.16, 0.35 | < 0.001 |

| Other Injury | 1.90 | 1.50, 2.42 | < 0.001 |

| Hospital Factors | |||

| Trauma Center | |||

| No | Ref. | — | |

| Yes | 0.30 | 0.22, 0.41 | < 0.001 |

| Hospital Region | < 0.01 | ||

| Northeast | Ref. | — | |

| Midwest | 1.28 | 0.84, 1.93 | |

| South | 1.54 | 1.12, 2.11 | |

| West | 0.73 | 0.46, 1.16 | |

| Volume of children < 2# | < 0.001 | ||

| Low | Ref. | — | |

| Medium | 0.68 | 0.42, 1.09 | |

| High | 0.39 | 0.25, 0.62 |

Adjusted for age, sex, injury type, hospital trauma center, hospital region, ED volume of children less than 2 years old, payer status, ISS category, and interaction between payer status and ISS category. The results of the interaction analysis are displayed in Figure 2.

Reference group for each injury type is absence of each respective injury type. For example, reference for fracture is no fracture.

ED volume of children <2 was calculated using all hospitals in the NEDS. Because not all hospitals evaluated children for abuse, the distribution of this categorical variable in our study cohort does not equal low (25%), medium (50%), high (25%).

There were differences in discharge decisions based on payer type, which were modified by injury severity (P = .02). Figure 2 displays the adjusted percentage discharged by payer type and injury severity. The adjusted percentage discharged of publicly insured children with low injury severity (ISS 1-4) was 56.2% (95% CI 51.6, 60.7). By comparison, the adjusted percentages discharged were greater among both privately insured children at 69.9% (95% CI 64.4, 75.5) and for self-pay children at 72.9% (95% CI 67.4, 78.4). Similar results were found among those with an ISS of 0 or incalculable. No significant differences were found in the adjusted percentage discharged of severely injured children by payer.

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted Percentages Discharged by Injury Severity and Payer Type.

The above percentages discharged were calculated adjusting for age, sex, injury type, trauma designation, hospital region, volume of children < 2 years of age, and the main effects of injury severity and payer type.

*Within the starred injury severity categories, the adjusted percentage discharged of publically insured children was significantly (P < 0.001) lower than the percentages discharged of private and self-pay children in pairwise comparisons.

DISCUSSION

In our study of ED visits, we identified 37,655 ED encounters of children less than 2 years diagnosed with physical abuse from 2006 to 2012 and found that approximately half (51.8%) resulted in discharge from the ED. We identified differences in disposition by payer among non-severely injured children, with a lower adjusted percentage discharged among publicly insured children compared with privately insured or self-pay children. Our findings also revealed questions about how physical abuse diagnosis codes are employed in EDs.

Our results underscore differences in discharge decisions by insurance type among physically abused children with low injury severity. Children with ISS scores less than 5 likely represent children who may not require hospitalization for medical stabilization. In these cases disposition decisions may involve both child welfare and medical input. The discrepancy in disposition between publicly and privately insured children may be due to biases in SES status and risk assessment, such that families with lower SES are viewed as being higher risk. However, if SES-based biases are the primary driver, the discrepancy in disposition between publicly insured and self-pay individuals is difficult to explain. Providers may have higher thresholds for admission for self-pay patients, taking into account the financial burden to the family and, potentially, concerns about reimbursement. However, consideration of family preferences is likely lower in cases of child abuse than in traditional medical indications for admission. Alternatively, insurance type may be a proxy for an aspect of the disposition decision and risk assessment not captured in the NEDS.

This variation in disposition decisions by payer may not reflect disparities unique to abused children. Disposition decisions favoring admission of publicly insured over privately insured and self-pay or uninsured individuals exist among children with traumatic brain injury,1 children with injuries not limited to abuse,2 and among adult and pediatric trauma victims.3 Children with cancer who are self-pay are more likely to be discharged than those with public or private insurance.4 Whether the primary drivers of disposition decisions in the above cases are analogous to those in cases of physical abuse is unknown.

Our results highlight questions about how physical abuse billing codes are employed, as nearly one-fifth of children with a diagnosis of physical abuse did not have an ICD-9-CM injury code. This result was not explained by our inclusion of the more nonspecific codes of 995.50 and 995.59 in our definition of physical abuse. Providers and institutions may not separately code for both physical abuse and an associated injury even when clear injuries are present. Providers may also employ child abuse codes to represent children who were brought to the ED due to concerns for child abuse whose evaluations did not reveal injuries, such as in cases of evaluations of siblings of abused children. Although we excluded children with late effects of injuries, we cannot be certain that all remaining children had newly identified injuries associated with abuse.

Our use of administrative data imposed certain limitations. First, we were unable to interpret the appropriateness of the final disposition or under whose care a child was discharged. Because disposition decisions are based on many factors, there is no appropriate or ideal percentage of children discharged or admitted. Second, there may have been misclassification of children as abused, and not all abused children may have been identifiable through abuse billing codes. Third, other factors important to ED providers and child protective services that may contribute to disposition decisions may have not been captured in the NEDS. For example, we were unable to evaluate whether the child was at risk for further contact with a perpetrator. We could not evaluate the effect of racial biases, as race is not included in the NEDS. Fourth, we were unable to discern whether our cohort included repeated visits from select children. Fifth, not all injuries may have been captured in billing data, which may have led to lower ISS scores. However, it is likely that more minor injuries would be omitted from billing data, which would minimize any misclassification. Lastly, there was no validated process for identifying abused children in the ED through billing codes. However, controlling for ISS successfully categorized injuries based on severity. Most importantly, when no injury was identified or calculable, the results were similar to when a minor or moderate injury was identified (ISS = 1 - 4).

In summary, we utilized a national ED dataset to demonstrate that the majority of physically abused young children are discharged from the ED, and that there are differences in the percentage discharged based on payer type in children without severe injuries. This observation that the discharge disposition of abused children may be related to payer type is a potentially concerning finding and merits future study to ensure that biases do not play a role in disposition decisions. Future work should evaluate outcomes of discharged versus admitted young physically abused children, explore disparities in disposition decisions by SES, and validate the use of billing codes in the diagnosis of abuse in the emergency setting.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (F32HS024194). Salary support was provided by the National Institutes of Health/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5T32H060550-05 [to M.H.], 1K23HD071967-04 [to J.W.], and K08HD073241 [to M.Z.]). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia has received payment for J.W.’s expert testimony following subpoenas in cases for suspected child abuse.

Abbreviations

- AIS

Abbreviated Injury Scale

- CI

Confidence Interval

- E-code

External cause of injury code

- ED

Emergency Department

- HCUP

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- MAIS

Maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale

- NEDS

Nationwide Emergency Department Sample

- ISS

Injury Severity Score

- SES

Socioeconomic Status

Footnotes

The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McCarthy ML, Serpi T, Kufera JA, Demeter LA, Paidas C. Factors influencing admission among children with a traumatic brain injury. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:684–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arroyo AC, Ewen Wang N, Saynina O, Bhattacharya J, Wise PH. The association between insurance status and emergency department disposition of injured California children. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:541–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selassie AW, McCarthy ML, Pickelsimer EE. The influence of insurance, race, and gender on emergency department disposition. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1260–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller EL, Sabbatini A, Gebremariam A, Mody R, Sung L, Macy ML. Why pediatric patients with cancer visit the emergency department: United States, 2006-2010. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:490–5. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Beureau. [2015 Aug 19];Child Maltreatment 2013. 2015 Jan 15; [Report on the internet]. Available from: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2013.pdf.

- 6.Christian CW Committee on Child Abuse and Negect, American Academy of Pediatrics. The evaluation of suspected child physical abuse. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e1337–54. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rangel EL, Cook BS, Bennett BL, Shebesta K, Ying J, Falcone RA. Eliminating disparity in evaluation for abuse in infants with head injury: use of a screening guideline. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.02.044. discussion 34-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood JN, Hall M, Schilling S, Keren R, Mitra N, Rubin DM. Disparities in the evaluation and diagnosis of abuse among infants with traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics. 2010;126:408–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood JN, French B, Song L, Feudtner C. Evaluation for Occult Fractures in Injured Children. Pediatrics. 2015;136:232–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lane WG, Dubowitz H. What Factors Affect the Identification and Reporting of Child Abuse-related Fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;461:219–25. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31805c0849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laskey AL, Stump TE, Perkins SM, Zimet GD, Sherman SJ, Downs SM. Influence of race and socioeconomic status on the diagnosis of child abuse: a randomized study. J Pediatr. 2012;160:1003–8. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood JN, Christian CW, Adams CM, Rubin DM. Skeletal surveys in infants with isolated skull fractures. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e247–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Intoduction to the HCUP Nationwide Emegency Department Sample (NEDS) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. [1 Mar 2015];2011 NEDS Errata Notification. 2015 Feb 23; [Internet]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/neds/2011NEDSErrataNotification022415.pdf.

- 15.Allareddy V, Asad R, Lee MK, Nalliah RP, Rampa S, Speicher DG, et al. Hospital based emergency department visits attributed to child physical abuse in United States: predictors of inhospital mortality. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King AJ, Farst KJ, Jaeger MW, Onukwube JI, Robbins JM. Maltreatment-Related Emergency Department Visits Among Children 0 to 3 Years Old in the United States. Child Maltreat. 2015;20:151–61. doi: 10.1177/1077559514567176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hooft A, Ronda J, Schaeffer P, Asnes AG, Leventhal JM. Identification of physical abuse cases in hospitalized children: accuracy of International Classification of Diseases codes. J Pediatr. 2013;162:80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacKenzie EJ, Steinwachs DM, Shankar B. Classifying trauma severity based on hospital discharge diagnoses. Validation of an ICD-9CM to AIS-85 conversion table. Med Care. 1989;27:412–22. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198904000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durbin DR, Localio AR, MacKenzie EJ. Validation of the ICD/AIS MAP for pediatric use. Inj Prev. 2001;7:96–9. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine. Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) 2005 - Update 2008. Barrington, IL: Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine; 2008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graubard BI, Korn EL. Predictive Margins with Survey Data. Biometrics. 1999;55:652–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]