Abstract

Anxiety Coach is a smartphone application (“app”) for iOS devices that is billed as a self-help program for anxiety in youth and adults. The app is currently available in the iTunes store for a one-time fee of $4.99. Anxiety Coach is organized around three related content areas: (a) self-monitoring of anxiety symptoms, (b) learning about anxiety and its treatment, and (c) guiding users through the development of a fear hierarchy and completion of exposure tasks. Although the app includes psychoeducation about anxiety as well as information regarding specific skills individuals can use to cope with anxiety (e.g., cognitive restructuring), the primary focus of the app is on exposure tasks. As such, the app includes a large library of potential exposure tasks that are relevant to treating common fears and worries, making Anxiety Coach useful to clients and clinicians alike. Additionally, Anxiety Coach prompts users to provide fear ratings while they are carrying out an exposure task and displays a message instructing users to stop the exposure once fear ratings drop by half. These features work together to create an app that has the potential to greatly increase the reach of exposure-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety.

Keywords: Anxiety Coach, mobile app, exposure task, cognitive behavioral therapy, anxiety

Description

Anxiety Coach is a smartphone application (“app”) for iOS devices that is intended to be a comprehensive self-help program for reducing a variety of anxiety symptoms. However, certain aspects of the app also have the potential to be useful for clinicians treating clients with anxiety disorders. The app is available for download from the iTunes store. Though costs may change, it is currently available for a one-time fee of $4.99 (Mayo Clinic, 2016). Anxiety Coach was designed to be used by individuals of all ages, but the current design of the app is utilitarian and does not include pictures and other activities that would appeal to younger children. Thus, the app is likely most appealing to adolescents and adults. The primary focus of Anxiety Coach is on creating a fear hierarchy and conducting exposure tasks, but the app also includes an assessment module and a teaching module that provides users with information about anxiety and its treatment.

The assessment module includes a self-test that asks users to use a Likert-type scale to rate the frequency with which they experience anxiety symptoms corresponding to the following anxiety and related disorders: generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), specific phobias (SP), panic disorder (PD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). After users complete the self-test, the app displays a screen indicating the anxiety and/or related disorder(s) that fit most closely with the users’ responses to the self-test. In addition to the self-test, the assessment module includes a platform for users to provide daily ratings of their anxiety symptoms on a scale of 0 (no anxiety) to 100 (most anxiety imaginable). Users may track their progress over time by retaking the self-test and daily symptom rating; the app provides graphical representations of an individual user’s scores on these tests over time.

The teaching module contains psychoeducational material regarding how to use the application, the cognitive-behavioral conceptualization of anxiety disorders, information on specific anxiety disorders, explanations of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and advice for finding a qualified local CBT provider. This information is presented in a text-based format, though the developers are planning to add interactive components (e.g., videos, animations, etc.) in the future (S. Whiteside, personal communication, February 5, 2016).

The final module helps users create and begin to use an exposure hierarchy. Users may search through a vast database of potential exposure tasks for a variety of common fears and worries. This database is organized by fear and includes topics such as “worrying a lot,” “social situations for youth,” “talking in public,” “germs, dirt, contamination,” “heights, things, other situations,” “animals,” “being away from parents,” “panic attacks,” and “memories of a trauma.” Under each heading is a subheading that includes more specific fears and worries that allows users to sort through this vast database efficiently. Under this subheading is a suggested exposure hierarchy that can be copied in full to a user’s “To-Do List” or the user may select specific exposure tasks to add to his or her “To-Do List.” Once the hierarchy is created, it can be reorganized and added to on an ongoing basis. When a user selects an exposure task from his or her “To Do List,” the app prompts the user to indicate his or her estimation of the likelihood of a feared outcome. If the user inputs a high rating, the app provides information on how to challenge these anxious thoughts. Once a user challenges his/her anxious thoughts, the app prompts the user to provide another estimate of the likelihood of a feared outcome. This process repeats until a user indicates a relatively low likelihood of a feared outcome. Following this procedure, the app asks users to provide a fear rating before they begin the exposure task and prompts users to provide fear ratings every 2 minutes throughout the exposure task. Anxiety Coach will automatically graph these fear ratings and provide a reference line to indicate when fear ratings have reduced by half. Users are encouraged to continue doing a given exposure task until their fear rating drops by 50%. Once the exposure task ends, the app prompts users to rate their impression of how the exposure task went. Based on a user’s response to this question, further information is provided regarding how to cope during exposure tasks, or alternatively, a congratulatory message is displayed. Users may view their practice history to examine detailed information regarding each exposure task they have completed using the app.

Background

The development of Anxiety Coach was a collaborative effort between Dr. Stephen Whiteside of the Mayo Clinic and Dr. Jonathan Abramowitz of the University of North Carolina. The app’s developers state that the goal of the app is “to make exposure therapy more accessible … by disseminating exposure-based CBT directly to patients and consumers” (S. Whiteside, personal communication, February 5, 2016). After reviewing available apps for anxiety in the iTunes and Google Play stores, Drs. Whiteside and Abramowitz were frustrated that they could not find an app that provided step-by-step assistance for doing good exposure tasks. Given that exposure tasks have been shown to be a key component of CBT for anxiety disorders (e.g., Kendall et al., 2005; Peris et al., 2015; Tiwari, Kendall, Hoff, Harrison, & Fizur, 2013), Drs. Whiteside and Abramowitz saw the need for an app focusing on exposure tasks, so they applied for a grant through the Mayo Clinic’s Center for Innovation to develop Anxiety Coach.

When developing Anxiety Coach, Drs. Whiteside and Abramowitz wanted to make sure that the app clearly emphasized the importance of exposure tasks. This focus is readily apparent to users of the app—the description of Anxiety Coach on the iTunes store makes mention of the importance of exposure tasks, the design of the app is such that it encourages users to complete exposure tasks, and the majority of the app’s features are related to preparing for and executing exposure tasks. Given that a vast majority of community mental health providers do not regularly use exposures in their practice (Freiheit, Vye, Swan, & Cady, 2004; Hipol & Deacon, 2013), Anxiety Coach’s focus on exposure tasks is a refreshing and much-needed addition to clinicians’ mobile health (m-health) repertoire. The vast database of sample fear hierarchies contained within Anxiety Coach also has the potential to help clinicians lacking experience in exposure-based CBT for anxiety disorders decide on appropriate exposure tasks for a given client.

Seeing the potential utility of Anxiety Coach for clinicians, the app’s developers are currently creating a web-portal that allows clinicians to sign in and view their clients’ progress by examining detailed data regarding each exposure task a client has completed, daily ratings of anxiety severity, and results from the self-test (S. Whiteside, personal communication, February 5, 2016). A web-portal is also being developed for clients that will allow individuals to sign into the app online and restructure their exposure hierarchy, conduct an exposure task, track their symptoms, learn about the cognitive-behavioral conceptualization of anxiety, and learn strategies to cope with anxiety. Once this clinician web-portal is completed and available to the public, the use of Anxiety Coach as an adjunct to face-to-face treatment is likely to increase. Indeed, other smartphone apps that are designed to aid in the treatment of anxiety disorders include a clinician web-portal.

Several other smartphone apps exist that guide users in implementing CBT principles for anxiety disorders. For example, SmartCAT is an Android application for child anxiety that is designed to be used as an adjunct to face-to-face therapy (Pramana, Parmanto, Kendall, & Silk, 2014). SmartCAT includes a variety of modules that are designed to cue youth to use the specific CBT skills taught during in-person therapy sessions, engage youth in their real-world environments, communicate this information to therapists, and manage rewards for completing therapeutic homework assignments. Preliminary research on SmartCAT suggests that users find it easy to use and acceptable (Pramana et al., 2014). However, unlike Anxiety Coach, which puts the focus on exposure tasks, SmartCAT includes a variety of treatment components. This broader focus has the potential to increase the utility of the app, but may also have the unwanted effect of shifting users’ focus away from exposure tasks and towards relaxation techniques or other CBT-based strategies that have been shown to be less important components of CBT for anxiety disorders (e.g., Peris et al., 2015).

Appropriateness of Content

Recent estimates suggest that 73% of teens and 64% of adults own a smartphone (Pew Research Center, 2015a, 2015b). This number is likely to increase in the coming years as the ratio of smartphone users to traditional cell phone users continues to increase (Pew Research Center, 2014). Given that a large proportion of individuals with anxiety disorders do not have access to evidence-based mental health care (Merikangas et al., 2010; Wilkinson, 2007), there is great potential for m-health interventions like Anxiety Coach to improve the reach of evidence-based treatments is large. Furthermore, a quick search in the iTunes store for “anxiety” will return hundreds of apps designed to help with anxiety. However, the vast majority of these apps focus on relaxation strategies and self-hypnosis, which have not been found to be key components in the treatment of anxiety disorders (e.g., Peris et al., 2015). Thus, Anxiety Coach’s primary focus on helping users conduct exposure tasks is largely unique to the m-health field and represents a much-needed addition to the m-health clinical repertoire.

The mobile format of Anxiety Coach provides users with a number of advantages. Used as an adjunct to face-to-face treatment, smartphone apps allow patients to access information regarding their care anywhere and at any time of day. Smartphone apps also benefit from cost-efficiency, a high degree of scalability, and the ability to deliver information consistently to a wide audience. Once the clinician web-portal is open, Anxiety Coach will also allow clinicians to monitor their clients’ progress in real-time and without retrospective recall bias. This may prompt conversations during session that would have otherwise not happened because a client was not able to freely recall a particular period of high anxiety, but may be more likely to recall it when presented with the anxiety ratings he or she made in the app at that time.

Research Evidence

There have been two articles published to date that have reported on client outcomes as well as feasibility and acceptability data from Anxiety Coach. Whiteside and colleagues (2014) presented two case studies of Anxiety Coach used as an adjunct to face-to-face exposure and response prevention (ERP) treatment for pediatric OCD. In one case presentation, the authors conducted an intake evaluation of a 10-year-old Caucasian female who met diagnostic criteria for OCD. Symptom measures revealed this client’s OCD symptoms fell in the moderate range. After two initial meetings, the client was provided with the Anxiety Coach app and encouraged to complete exposure tasks at home with the help of the app. Approximately 4 months after the first assessment, the client completed a posttreatment evaluation. Data revealed that this client no longer met criteria for OCD at posttreatment after using Anxiety Coach with minimal therapist contact. A second case was presented that examined the use of Anxiety Coach with a 16-year-old Caucasian male with severe OCD, social anxiety disorder, and major depression. This client completed nine in-person sessions over the course of 3 months, and used Anxiety Coach between these in-person sessions. Posttreatment data indicated that although this client still met criteria for OCD, symptom severity at posttreatment fell in the mild range (Whiteside et al., 2014). Both clients presented in this article reported a positive experience using Anxiety Coach and that they found it to be a helpful addition to face-to-face treatment. Taken together, these data suggest that Anxiety Coach has the potential to serve as a useful adjunct to face-to-face therapy that may be able to reduce the amount of time therapists and other mental health providers spend with each client, thus reducing the cost of mental health care.

A second article presented user data from the first year that Anxiety Coach was publicly available (Whiteside, in press). A total of 169 children and adolescents aged 5 to 17 years (65.1% female) downloaded the application. On average, these 169 youth used the application seven times, which the authors suggest shows that most children found the application engaging. Among both youth and adult users, a total of 2,449 individuals downloaded Anxiety Coach in the first year it was available in the iTunes store. Data from these users suggested that the majority (62.3%) used the app to take a self-assessment of anxiety symptoms, 37.4% used the app to create a fear hierarchy, and 4.7% used the app to complete an exposure task (Whiteside, in press). It should be noted that exposure task data reflect only those participants who used the app to record fear ratings during an exposure and may not reflect all those who completed an exposure without using the app to provide in vivo fear ratings.

Further research is needed to directly examine the use of Anxiety Coach as an adjunct to face-to-face treatment compared to face-to-face treatment only. Such a study would provide valuable information on the ability of Anxiety Coach to enhance clinical outcomes. Additionally, further research is needed to examine how users who downloaded Anxiety Coach from the iTunes store engage with the app. Do these individuals use the app multiple times? Does Anxiety Coach help individuals who otherwise have not considered exposure-based treatment connect with exposure-based treatment providers (i.e., provide a foot in the door to face-to-face treatment)? What are the outcomes from users who download the app without therapist support? Is there a way to engage these users with the app more fully so that a larger proportion completes exposure tasks? These questions remain unanswered, and much remains to be learned about the clinical utility of Anxiety Coach and other m-health applications.

Utility

Determining the utility of Anxiety Coach and other m-health applications is a burgeoning area of research. However, given that compliance with between-session exposure tasks is frequently cited as a barrier to clients engaging with exposure-based strategies (Edelman & Chambless, 1993, 1995; Hudson & Kendall, 2002; Mausbach, Moore, Roesch, Cardenas, & Patterson, 2010), Anxiety Coach has the potential to address this concern. Whether or not Anxiety Coach actually improves clinical outcomes or not, the vast database of potential exposure tasks included in the Anxiety Coach app is likely to be useful to clients and clinicians alike. Moreover, Anxiety Coach may provide a useful addition to primary care offices, allowing nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and other non-mental-health providers to assess patients for anxiety. Those with elevated anxiety could download the app, and with the help of one of these providers, develop a fear hierarchy and begin conducting exposure tasks that day. Given the variety of barriers to accessing quality mental health care, using Anxiety Coach in such a manner has the potential to drastically increase the reach of evidence-based care.

Ease of Use/Overall Appeal

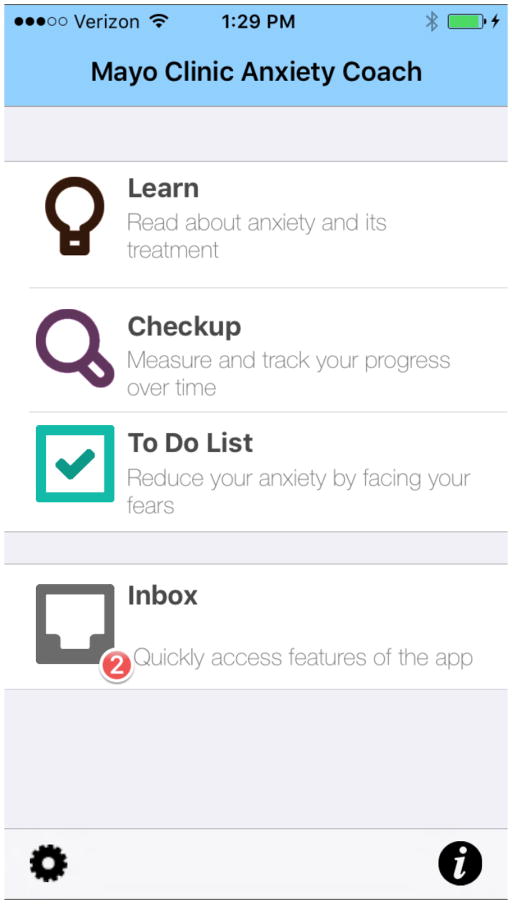

The layout of the Anxiety Coach app is very straightforward and easy to navigate. As soon as the app is opened, users are brought to the home page, which has four buttons: “Learn,” “Checkup,” “To-Do List,” and “Inbox” (see Figure 1). The “Learn” button takes users to a menu that provides information on using anxiety coach, the cognitive-behavioral conceptualization of anxiety, specific anxiety disorder diagnoses, treatment of anxiety, common issues individuals run into when using the app and when conducting exposures, and finding a therapist in users’ local communities. This information is presented as text, but the developers are planning to make the presentation of this information more interactive in the future through the use of audio-recordings, videos, and graphics (S. Whiteside, personal communication, February 5, 2016). Unfortunately, as the app currently stands, a portion of the text in the “Learn” section was not visible on my smartphone (iPhone 6). The app developers believe this glitch is specific to newer devices and operating systems, and that it will be fixed with a new release in the coming months (S. Whiteside, personal communication, August 31, 2016).

Figure 1.

Anxiety Coach home screen.

The “Checkup” button links users to the self-test, which helps users determine what disorders fit most closely with the anxiety symptoms they are experiencing, and the daily symptom checker, which allows users to rate their current anxiety symptoms on a scale of 0 to 100. Also included in the “Checkup” section are graphical representations of each self-test, daily symptom check, and exposure task that a user has completed using the app. The presentation of this information graphically allows users to monitor their progress over time.

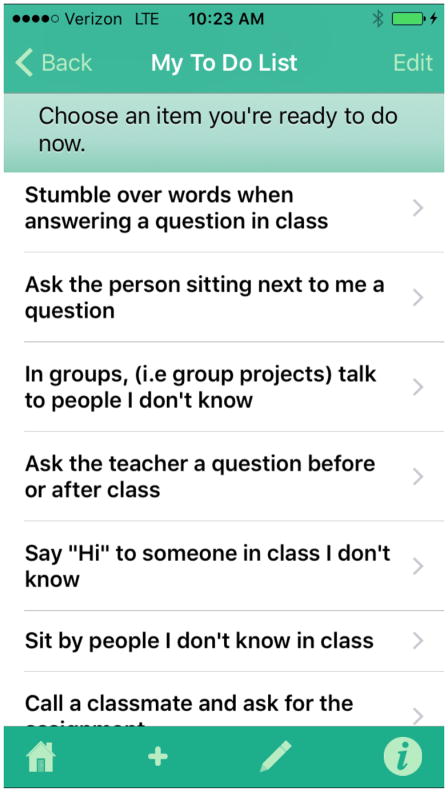

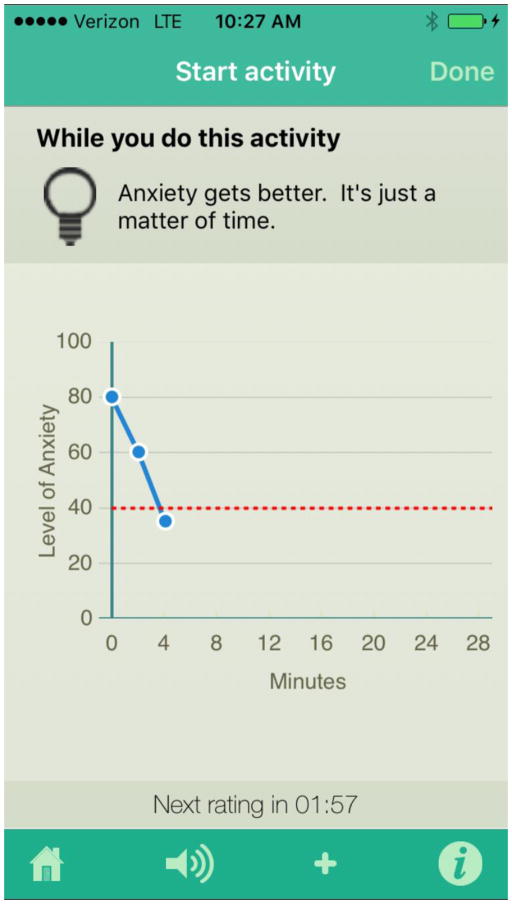

The “To-Do List” button allows users to access the vast database of sample exposure tasks and create their own fear hierarchies (see Figure 2). Users may update their hierarchy as often as they desire with sample exposure tasks from the app’s internal database or by adding their own via text-based entry. Once a user has created his or her fear hierarchy, users can click on a specific exposure task in their hierarchy to indicate they are about to begin that exposure task. Throughout the exposure task, the app prompts users for fear ratings every 2 minutes and graphs these ratings as over time (see Figure 3). One issue when using this portion of the app to complete an exposure task is that the 2-minute timer stops when the app is closed. Thus, unless users keep the app open while they are doing the exposure task, the app will not prompt them for fear ratings. This is problematic because users who are trying to use the app correctly may unintentionally begin to use the app in a manner consistent with a safety behavior—focusing more on the app during an exposure task than on the feared stimulus. This small caveat aside, I found developing a fear hierarchy and conducting exposures within the app to be a simple and pleasant experience.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of sample To-Do list

Figure 3.

Screenshot from user conducting an exposure task

Finally, the “Inbox” button alerts users to tasks that should be completed to get the most out of Anxiety Coach. These alerts arrive as notifications on users’ iOS devices. For example, after using the app for several months, I received an alert in my inbox to take a self-test to check in on my anxiety symptoms. The “Inbox” is also where users are provided with alerts to complete an exposure task from their fear hierarchy if they have not engaged with the app recently.

Taken together, I found the Anxiety Coach interface to be very easy to use. Information is organized intuitively, and by using subheadings appropriately, users are able to find the information they are looking for quickly. Once the minor bugs are fixed (i.e., all text displaying correctly, continuing to prompt users for fear ratings during an exposure when the app is closed), it is likely that users, regardless of their technological savvy, will find Anxiety Coach easy to use.

Conclusions

Strengths, Weaknesses, and Overview

The greatest strength of Anxiety Coach is its focus on exposure tasks. Unlike other apps for anxiety that include information on a variety of therapeutic techniques (most often relaxation and self-hypnosis) and may lead to confusion about which components are most important for coping with anxiety, Anxiety Coach makes clear that exposure tasks are an integral part of successful anxiety treatment. Further research is needed to determine whether the use of Anxiety Coach actually leads users to complete more exposures on their own compared to face-to-face CBT and other smartphone apps. The vast database of sample exposure tasks is likely to help both patients and clinicians develop appropriate fear hierarchies for an individual’s presenting difficulties. Furthermore, the in-app monitoring of fear ratings during an exposure task allows users to see their habituation curves throughout an exposure task. Results from the daily symptom monitor are presented in a way that clients can easily visualize how their anxiety symptoms are changing over time. The self-test is likely to help users who have not yet sought therapy determine what anxiety disorder their symptoms most closely resemble, which may help them choose an experienced provider in the future. Finally, clients are likely to find the information presented in the learning module useful regardless of whether they are using Anxiety Coach as an adjunct to face-to-face therapy or as a stand-alone self-help program.

The greatest weakness of Anxiety Coach at the time of this writing is the lack of a clinician web-portal. The only research available to date examining Anxiety Coach uses the app as an adjunct to treatment. Until a web-portal is available to the public, clinicians may find it difficult or awkward to use Anxiety Coach with their clients during session. However, the developers are currently working on developing a clinician web-portal (S. Whiteside, personal communication, February 5, 2016), so this critique is likely to be short lived. For the time being, Anxiety Coach may best be used as a stand-alone self-help program rather than an adjunct to face-to-face treatment. Another minor weakness of Anxiety Coach is the presence of a few minor technical glitches (see Ease of Use section above). Technical glitches are par for the course when working with information technology; it is how quickly these glitches are fixed that is the real metric of a good program. Only time will tell how quickly these particular issues are fixed. Finally, Anxiety Coach is currently only available on iOS devices so Android users must wait for an Android-compatible version to be released. This is also one of the app developers’ plans for the future (S. Whiteside, personal communication, February 5, 2016), but it is unclear how long it will be before Anxiety Coach is available in the Google Play store.

Overall, Anxiety Coach represents a much-needed addition to the m-health clinical toolbox. The app’s focus on exposure tasks reflects our current understanding of the mechanisms of change in CBT for anxiety disorders and is likely to help users avoid the confusion that could result from trying to figure out what part of the app is most important to helping them cope with anxiety. The vast database of exposure tasks included in Anxiety Coach includes tasks relevant to a broad range of ages, which may help less experienced clinicians determine an appropriate fear hierarchy and appropriate exposure tasks for a given client. Until additional research demonstrates the efficacy of Anxiety Coach as a stand-alone treatment, clinicians should carefully consider whether or not to recommend Anxiety Coach in lieu of face-to-face treatment. However, when compared with the vast majority of other apps currently available for anxiety, Anxiety Coach is a strong contender for the top spot and is likely to facilitate the dissemination of exposure-based strategies for the anxiety and related disorders.

Table 1.

Evaluative Ratings for Anxiety Coach

| Criterion | Score |

|---|---|

| Appropriateness of Content | 5 |

| Research Evidence | 2 |

| Utility | 4 |

| Ease of Use/Overall Appeal | 4 |

Note: 1 = Poor, 2 = Marginal, 3 = Satisfactory, 4 = Very Good, 5 = Outstanding, NP = Not Present, NA = Not Applicable.

Table 2.

Summary of Anxiety Coach

| Resource name | Web Homepage | Target Audience and Purpose | Strengths | Weaknesses | Overall Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Coach | https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/anxietycoach/id565943257?mt=8 | Comprehensive self-help program for reducing a variety of anxiety symptoms in youth and adults. Anxiety Coach has a primary focus on creating a fear hierarchy and conducting exposure tasks, but the app also includes an assessment module and a psychoeducation module. | The app has a clear focus on exposure tasks. Anxiety Coach clearly informs users that exposure tasks are an integral part of successful anxiety treatment and assists with creating and implementing an exposure hierarchy. Includes a useful monitoring system for monitoring SUDS ratings during exposures, as well as an assessment module allowing users to monitor anxiety symptoms over time. Overall, the user interface is quite intuitive and easy to use. | There is no clinician web-portal, which may make it difficult or awkward to use Anxiety Coach during session or to monitor the completion of exposure tasks between sessions. There are also a few minor technical glitches with the app, but these should be resolved with a future release. | Anxiety Coach represents a much-needed addition to the m-health toolbox. The app’s focus on exposure tasks reflects our current understanding of mechanisms of change in CBT for the anxiety disorders. The app includes a vast database of potential exposure tasks that are relevant to a broad range of ages. However, until additional research demonstrates the efficacy of Anxiety Coach as a standalone treatment, clinicians should be wary of recommending Anxiety Coach in lieu of face-to-face CBT treatment. |

Highlights.

Anxiety Coach is an application for iOS devices that is intended to be a comprehensive self-help program for reducing symptoms of anxiety.

The primary focus of Anxiety Coach is on helping its users conduct exposure tasks.

The app also includes assessment and psychoeducation modules.

Additional research is needed to examine Anxiety Coach as a standalone self-help program.

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number F31MH104105.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Edelman RE, Chambless DL. Compliance during sessions and homework in exposure-based treatment of agoraphobia. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1993;31:767–773. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90007-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman RE, Chambless DL. Adherence during sessions and homework in cognitive-behavioral group treatment of social phobia. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1995;33:573–577. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00068-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiheit SR, Vye C, Swan R, Cady M. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety: Is dissemination working? Behavior Therapist. 2004;27:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hipol LJ, Deacon BJ. Dissemination of evidence-based practices for anxiety disorders in Wyoming: A survey of practicing psychotherapists. Behavior Modification. 2013;37:170–188. doi: 10.1177/0145445512458794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL, Kendall PC. Showing you can do it: Homework in therapy for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58:525–534. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Robin JA, Hedtke K, Suveg CM, Flannery-Schroeder E, Gosch E. Considering CBT with anxious youth? Think exposures. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2005;12:136–150. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(05)80048-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Moore R, Roesch S, Cardenas V, Patterson TL. The relationship between homework compliance and therapy outcomes: An updated meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy Research. 2010;34:429–238. doi: 10.1007/s10608-010-9297-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo Clinic. Anxiety Coach (Version 1.3.2) [Mobile application software] 2016 Retrieved from https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/anxietycoach/id565943257?mt=8.

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics. 2010;125:75–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris TS, Compton SN, Kendall PC, Birmaher B, Sherrill JT, March J, … Piacentini J. Trajectories of change in youth anxiety during cognitive-behavior therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83:239–252. doi: 10.1037/a0038402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Teens, social media, & technology overview 2015. 2015a Retrieved February 6, 2016, from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/

- Pew Research Center. US smartphone use in 2015. 2015b Retrieved February 6, 2016, from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015/

- Pramana G, Parmanto B, Kendall PC, Silk JS. The SmartCAT: An mHealth platform for ecological momentary intervention (EMI) in child anxiety treatment. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2014;20:419–427. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S, Kendall PC, Hoff AL, Harrison JP, Fizur P. Characteristics of exposure sessions as predictors of treatment response in anxious youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42:34–43. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.738454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SPH. Mobile device-based applications for childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. :1–6. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0010. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SPH, Ale CM, Vikers Douglas K, Tiede MS, Dammann JE. Case examples of enhancing pediatric OCD treatment with a smartphone application. Clinical Case Studies. 2014;13:80–94. doi: 10.1177/1534650113504822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson E. Access to psychological therapies almost non-existent. The Lancet. 2007;370:121–122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]