Abstract

Background/objective

Patients with polymyositis (PM) and dermatomyositis (DM) may have an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE); however, no general population data are available to date. The purpose of this study was to estimate the future risk and time trends of new VTE (deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE)) in individuals with incident PM/DM at the general population level.

Methods

We assembled a retrospective cohort of all patients with incident PM/DM in British Columbia and a corresponding comparison cohort of up to 10 age-matched, sex-matched and entry-time-matched individuals from the general population. We calculated incidence rate ratios (IRR) for VTE, DVT and PE and stratified by disease duration. We calculated HRs adjusting for relevant confounders.

Results

Among 752 cases with inflammatory myopathies, 443 had PM (58% female, mean age 60 years) and 355 had DM (65% female, mean age 56 years); 46 subjects developed both diseases. The corresponding IRRs (95% CI) for VTE, DVT and PE in PM were 8.14 (4.62 to 13.99), 6.16 (2.50 to 13.92) and 9.42 (4.59 to 18.70), respectively. Overall, the highest IRRs for VTE, DVT and PE were observed in the first year after PM diagnosis (25.25, 9.19 and 38.74, respectively). Fully adjusted HRs for VTE, DVT and PE remained statistically significant (7.0 (3.34 to 14.64), 6.16 (2.07 to 18.35), 7.23 (2.86 to 18.29), respectively). Similar trends were seen in DM.

Conclusions

These findings provide the first general population-based evidence that patients with PM/DM have an increased risk of VTE. Increased vigilance of this serious but preventable complication is recommended.

Keywords: Dermatomyositis, Polymyositis, Pulmonary Embolism, Deep Venous Thrombosis, Venous Thromboembolism

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory myopathies, including polymyositis (PM) and dermatomyositis (DM), are rare connective tissue diseases characterized by chronic muscle inflammation and weakness. Prevalence of these conditions is estimated to be between 5.4 and 21.5 per 100,000 in Canada. (1, 2) These systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases are associated with increased morbidity and mortality, and a high economic burden. (3)

Prior to the introduction of corticosteroids in the treatment of PM and DM, the prognosis was extremely poor with a mortality rate as high as 50 to 61%. (4) Survival rates have significantly improved since then, but the overall risk of mortality is still high, with recent studies showing a three-fold (5) to four-fold (6) higher risk than the general population.

While an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been shown in other autoimmune rheumatic diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, (7–9) scleroderma, (10) ankylosing spondylitis, (11) and systemic lupus erythematosus, (12, 13) data on CVD in patients with inflammatory myopathies is scarce, and has focused almost entirely on atherosclerotic disease. (14, 15)

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) includes deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), and represents the third most common cardiovascular event after myocardial infarction and stroke. (16) PE has a mortality rate of 15% in the first three months after diagnosis (17) making it potentially as deadly as acute myocardial infarction, and survivors often experience serious and costly long-term complications. (18)

The risk of VTE in individuals with inflammatory myopathies has largely been ignored despite several plausible mechanisms. Systemic inflammation associated with PM and DM may modulate thrombotic responses by up-regulating procoagulants, down-regulating anticoagulants and suppressing fibrinolysis. (16) Since the link between inflammation and VTE has started to emerge, some hospital-based studies have been conducted to investigate this association for a wide range of autoimmune diseases, and have reported an increased risk of VTE in patients with inflammatory myopathies. (19–22) However, their findings are limited because they are based on purely hospital based samples, and only one study (21) was able to adjust for potential confounding factors and medication use.

It is largely unknown whether the increased risk of VTE seen in these inpatient studies is applicable to PM/DM from the general population. Since PE represents a common and often fatal vascular event, (23) accurate understanding of this risk among patients with inflammatory myopathies is crucial. To address this issue, we evaluated the risk of incident DVT and PE among incident PM and DM patients compared to controls in an unselected general population context.

METHODS

Data Source

Universal health coverage is a feature of the province of British Columbia (BC, population ~ 4.7 million) in Canada. Population Data (PopData) BC (formerly known as the British Columbia Linked Health Databases or BCLHD) captures population-based administrative data including linkable data files on all provincially funded health care professional visits, hospital admissions, interventions, investigations, demographic data, cancer registry and vital statistics since 1990. Furthermore, PopData BC encompasses the comprehensive prescription drug database, PharmaNet, with data since 1996. Numerous general population-based studies have been successfully conducted based on these databases. (24–28)

Study Design

We conducted matched cohort analyses for incident VTE (i.e. DVT or PE) among individuals with incident PM (PM cohort) or DM (DM cohort) as compared with individuals without PM or DM (comparison cohorts), using data from PopData BC. For the comparison cohorts, we matched up to 10 individuals without PM/DM to each PM/DM case based on age, sex, and calendar year of study entry, randomly selected from the general population.

Incident PM/DM Cohort

We created incident PM and DM cohorts with cases diagnosed for the first time between January 1996 and December 2010 with no PM/DM history or diagnosis recorded over the prior six years (i.e. from January 1990). Our study definition of PM and DM consisted of: a) ≥ 18 years of age; b) One International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code by a rheumatologist (710.4 for PM; 710.3 for DM) or from a hospital (ICD-9-CM same as above, or ICD-10-CM M33.0, M33.1 or M33.9 for DM; M33.2 for PM) or c) two ICD-9-CM codes for PM or DM at least two months and no more than two years apart by a non-rheumatologist physician. Similar PM/DM case definitions have been used in previous studies in Canada and found to have a specificity of 96.4% in the context of systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases. (29) To further improve specificity, we excluded individuals with at least two visits ≥ two months apart subsequent to the PM/DM diagnostic visit with other inflammatory disease diagnoses (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, systemic lupus erythematosus, giant cell arteritis).

Ascertainment of DVT and PE

Incident DVT and PE cases were defined by a corresponding ICD code and prescription of anticoagulant therapy (heparin, warfarin sodium or a similar agent). (30) The codes used were: DVT (ICD-9-CM: 453; ICD-10-CM: I82.4, I82.9) and PE (ICD-9-CM: 415.1, 673.2, 639.6; ICD-10-CM: O88.2, I26). Since VTE is a potentially fatal disease, we also included patients with a fatal outcome. Because a patient may have died before anticoagulation treatment, patients with a recorded code of DVT or PE were included in the absence of recorded anticoagulant therapy if there was a fatal outcome within 2 months of diagnosis. These definitions have been successfully used in previous studies and found to have a positive predictive value of 94% in a general practice database. (30)

Assessment of Covariates

Covariates consisted of potential risk factors of VTE assessed during the year before the index date. These included relevant medical conditions (alcoholism, hypertension, varicose veins, inflammatory bowel disease, sepsis), trauma, fractures, surgery, healthcare utilization, and use of glucocorticoids, hormone replacement therapy, contraceptives or COX-2 inhibitors. Additionally, a modified Charlson’s co-morbidity index for administrative data was calculated in the year before index date. (31, 32)

Cohort Follow-Up

Our study cohorts spanned the period January 1, 1996 to December 31, 2010. Individuals with PM and DM entered the case cohort after all inclusion criteria had been met, and matched individuals entered the comparison cohort after a doctor’s visit or hospital admission in the same calendar year. Participants were followed until they either experienced an outcome, died, dis-enrolled from the health plan (left BC), or follow-up ended (December 31, 2010), whichever occurred first.

Statistical Analysis

We compared baseline characteristics between the PM/DM and control cohorts. We calculated the incidence rates (IR) per 1000 person-years (PY) for respective outcomes for the PM/DM and corresponding comparison cohorts. The associations between PM/DM and study outcomes are expressed as incidence rate ratios (IRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To evaluate the time-trend of VTE risk according to the time since PM/DM diagnosis, we estimated IRRs in one-year intervals, starting in the first year after diagnosis and up to five years after diagnosis.

We conducted Cox proportional hazard regressions (33) to assess the adjusted relative risk (RR) of VTE, DVT and PE associated with PM and DM after stratifying by matched variables (baseline age and sex). These multivariable analyses were adjusted for all covariates listed above and the effect of PM/DM on study outcomes was expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs. We also performed sub-group analyses according to sex.

We performed three sensitivity analyses. First, analysis with a stricter definition of PM/DM exposure was used, limited to subjects with ICD codes for PM/DM and the use of anti-rheumatic medications including glucocorticoids, antimalarials, methotrexate, and immunosuppressives between one month before and six months after the index date (date of diagnosis). Second, we estimated the cumulative incidence of each event accounting for the competing risk of death according to Lau et al (34) and expressed the results as sub-distribution HRs with 95% CIs. Third, to quantify the potential impact of unmeasured confounders, we performed sensitivity analyses which assessed how a hypothetical unmeasured confounder might have affected our estimates of the association between PM/DM and risk of VTE. (35) We simulated unmeasured confounders with their prevalences ranging from 10% to 20% in the PM/DM and comparison cohorts, and odds ratios (ORs) for the associations between the unmeasured confounder and both VTE and the exposures ranging from 1.3 to 3.0.

Analyses were performed with SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). For all RRs, we calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All p-values are two-sided.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

We identified 443 new cases with PM and 355 cases with DM. For each case, ten controls matched by birth year, sex, and calendar year of follow-up were randomly selected from the general population to create the control cohorts for PM (N=4,603) and DM (N=3,577). Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the cohorts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of PM, DM, and Comparison Cohorts at Baseline

| Variable | PM n = 443 |

Non-PM n = 4,603 |

P Value | DM n = 355 |

Non-DM n = 3,577 |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) years | 60.39 (15.62) | 60.53 (15.44) | NS | 55.9 (16.6) | 55.8 (16.5) | NS |

| Female | 257 (58.0) | 2678 (58.2) | NS | 229 (64.5) | 2,307 (64.5) | NS |

| Alcoholism | 5 (1.1) | 41 (0.9) | NS | 3 (0.8) | 36 (1) | NS |

| Hypertension | 136 (30.7) | 1222 (26.5) | NS | 96 (27) | 772 (21.6) | 0.02 |

| Sepsis | 3 (0.7) | 8 (0.2) | NS | 1 (0.3) | 9 (0.3) | NS |

| Varicose veins | 3 (0.7) | 49 (1.1) | NS | 2 (0.6) | 34 (1) | NS |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 3 (0.7) | 8 (0.2) | NS | 2 (0.6) | 8 (0.2) | NS |

| Trauma | 1 (0.2) | 19 (0.4) | NS | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.1) | NS |

| Fracture | 14 (3.2) | 69 (1.5) | 0.017 | 3 (0.8) | 42 (1.2) | NS |

| Surgery | 4 (0.9) | 30 (0.7) | NS | 4 (1.1) | 20 (0.6) | NS |

| Glucocorticoids | 203 (45.8) | 186 (4) | <0.001 | 198 (55.8) | 142 (4) | <0.001 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 30 (6.8) | 220 (4.8) | NS | 17 (4.8) | 184 (5.1) | NS |

| Contraceptives | 7 (1.6) | 89 (1.9) | NS | 15 (4.2) | 128 (3.6) | NS |

| Cox-2 inhibitors | 33 (7.4) | 145 (3.2) | <0.001 | 21 (5.9) | 101 (2.8) | 0.003 |

| Charlson’s comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 1.39 (1.94) | 0.44 (1.21) | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.86) | 0.36 (1.09) | <0.001 |

| Number of hospitalizations, mean (SD) | 0.9 (1.4) | 0.3 (0.8) | <0.001 | 0.66 (1.19) | 0.24 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Number of outpatient visits, mean (SD) | 129.54 (108.83) | 38.33 (52.2) | <0.001 | 123.26 (106.33) | 34.65 (49.31) | <0.001 |

Values are N (percentages) unless otherwise noted.

P values are estimated by either t-test (continuous) or Fisher’s exact test (categorical)

NS: Non-significant

Compared with the control groups, the PM and DM cases used more glucocorticoids, COX-2 inhibitors, had higher Charlson’s comorbidity index, and had more hospitalizations and outpatient visits during the 12 months prior to the diagnosis. In addition, the PM group had a significantly higher rate of fractures, and the DM group had a higher proportion with hypertension.

Association between a Diagnosis of PM/DM and Incident VTE

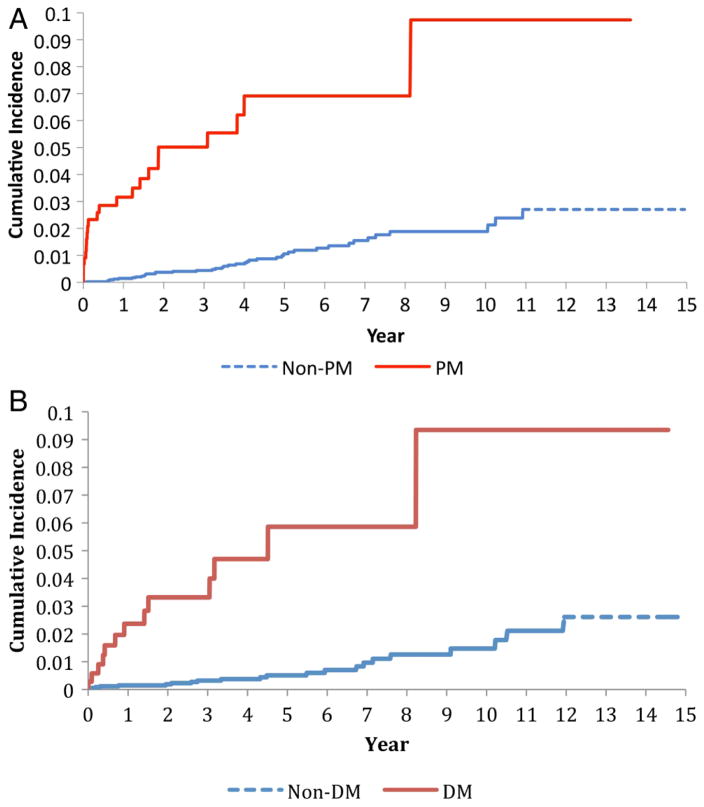

Overall, both PM and DM were significantly associated with an increased incidence of VTE as well as individual DVT and PE events (Table 2; Figure 1). Among individuals with PM, the IRs for VTE, DVT and PE were 16.49, 6.68 and 11.14 per 1000 PY, versus 2.03, 1.08 and 1.18 per 1000 PY in the comparison cohort. The corresponding age-, sex-, and entry-time-matched IRRs were 8.14 (95% CI; 4.62, 13.99), 6.16 (95% CI; 2.50, 13.92), and 9.42 (95% CI; 4.59, 18.70) for VTE, DVT and PE, respectively. Similar trends were seen for DM (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of DVT, PE and VTE according to PM or PM status

| PM n = 443 |

Non-PM n = 4,603 |

DM n = 355 |

Non-DM n = 3,577 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE | ||||

| VTE events, N | 22 | 41 | 13 | 22 |

| IR / 1000 PY | 16.49 | 2.03 | 12.42 | 1.39 |

| IRRs (95% CI) | 8.14 (4.62, 13.99) | 1.0 | 8.92 (4.13, 18.51) | 1.0 |

| DVT | ||||

| DVT events, N | 9 | 22 | 9 | 14 |

| IR / 1000 PY | 6.68 | 1.08 | 8.55 | 0.88 |

| IRRs (95% CI) | 6.16 (2.50, 13.92) | 1.0 | 9.66 (3.69, 23.96) | 1.0 |

| PE | ||||

| PE events, N | 15 | 24 | 5 | 11 |

| IR / 1000 PY | 11.14 | 1.18 | 4.70 | 0.69 |

| IRRs (95% CI) | 9.42 (4.59, 18.70) | 1.0 | 6.77 (1.84, 21.14) | 1.0 |

DVT, Deep vein thrombosis; IRR, Incidence rate ratio; PE, Pulmonary embolism; VTE, Venous thromboembolism

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of venous thromboembolism in the 443 cases with incident polymyositis (PM) (upper panel) and 355 cases with dermatomyositis (DM) (lower panel) as compared with age-matched, sex-matched and entry-time-matched controls randomly selected from the general population.

Overall, when we evaluated the impact of follow-up time after diagnosis of PM, the IRRs for VTE and PE events were substantially larger in the first year, whereas the IRR for DVT remained relatively constant throughout the first five years after diagnosis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Age and sex adjusted risk for PE, DVT and VTE in PM and DM according to follow-up period

| Time since diagnosis | VTE IRR (95% CI) |

DVT IRR (95% CI) |

PE IRR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM | n = 22 | n = 9 | n = 15 |

| < 1 year | 25.25 (8.96 – 81.02) | 9.19 (1.82 – 42.72) | 38.74 (9.98 – 219.06) |

| < 2 years | 15.84 (7.44 – 34.41) | 12.17 (3.64 – 40.67) | 14.68 (5.81 – 37.94) |

| < 3 years | 14.41 (6.93 – 30.20) | 12.68 (4.15 – 38.74) | 13.85 (5.60 – 34.65) |

| < 4 years | 12.02 (6.22 – 23.08) | 10.72 (3.93 – 28.45) | 11.36 (4.97 – 25.58) |

| < 5 years | 9.91 (5.37 – 18.00) | 7.18 (2.82 – 17.04) | 11.88 (5.37 – 25.97) |

| Total follow-up | 8.14 (4.62 – 13.99) | 6.16 (2.50 – 13.92) | 9.42 (4.59 – 18.70) |

| DM | n = 13 | n = 9 | n = 5 |

| < 1 year | 16.07 (4.39 – 64.23) | 14.33 (3.09 – 72.24) | 34.22 (2.75 – 1796.48) |

| < 2 years | 18.50 (5.88 – 63.18) | 17.22 (4.71 – 68.82) | 36.66 (2.94 – 1924.57) |

| < 3 years | 12.80 (4.50 – 36.40) | 14.89 (4.28 – 53.63) | 9.48 (1.39 – 56.06) |

| < 4 years | 14.51 (5.59 – 38.10) | 17.52 (5.33 – 61.26) | 10.41 (2.07 – 48.35) |

| < 5 years | 13.61 (5.59 – 33.12) | 15.24 (5.22 – 45.40) | 10.74 (2.13 – 49.89) |

| Total follow-up | 8.92 (4.13 – 18.51) | 9.66 (3.69 – 23.96) | 6.77 (1.84 – 21.14) |

DVT, Deep vein thrombosis; IRR, Incidence rate ratio; PE, Pulmonary embolism; VTE, Venous thromboembolism

After further adjustment for relevant risk factors, the corresponding multivariable HRs were 7.0 (95% CI; 3.34, 14.64), 6.16 (95% CI; 2.07, 18.35) and 7.23 (95% CI; 2.86, 18.29) for VTE, DVT and PE, respectively (Table 4). Similar trends were seen in the DM cohort, except for PE, which was not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis of the risk of VTE, DVT and PE in individuals with PM/DM

| PM n = 443 |

Non-PM n = 4,603 |

DM n = 355 |

Non-DM n = 3,577 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTE | ||||

| Multivariable HR (95% CI) | 7.0 (3.34, 14.64) | 1.0 | 8.39 (3.04, 23.14) | 1.0 |

| Females | 5.56 (2.11, 14.66) | 1.0 | 6.55 (1.98, 21.64) | 1.0 |

| Males | 9.83 (2.98, 32.41) | 1.0 | 11.09 (1.05, 116.8) | 1.0 |

| DVT | ||||

| Multivariable HR (95% CI) | 6.16 (2.07, 18.35) | 1.0 | 9.40 (2.88, 30.68) | 1.0 |

| Females | 5.29 (1.12, 24.94) | 1.0 | 10.12 (2.71, 37.81) | 1.0 |

| Males | 4.98 (0.90, 27.63) | 1.0 | 2.22 (0.07, 70.01) | 1.0 |

| PE | ||||

| Multivariable HR (95% CI) | 7.23 (2.86, 18.29) | 1.0 | 4.70 (0.85, 25.98) | 1.0 |

| Females | 6.46 (1.81, 23.0) | 1.0 | 1.54 (0.15, 16.19) | 1.0 |

| Males | 10.65 (2.46, 46.06) | 1.0 | 17.02 (0.61, 478.17) | 1.0 |

DVT, Deep vein thrombosis; HR, Hazard ratio; PE, Pulmonary embolism; VTE, Venous thromboembolism

Sensitivity Analysis

Of the 443 and 355 patients who met the criteria for PM and DM, 309 (70%) and 293 (83%) patients had anti-rheumatic prescriptions (Table 5). The HRs restricted to this group and the matching controls remained statistically significant. HRs from analysis of the association between PM/DM and study outcomes that accounted for the competing event of death gave slightly attenuated estimates, but remained significant (Table 5). Furthermore, in our sensitivity analyses for potential impact of unmeasured confounders, HRs remained significant even at the extreme values of 20% prevalence and an OR of 3.0 for the association between the hypothetical confounder and all outcomes except PE in DM (which was not significant in the primary analyses).

Table 5.

Sensitivity Analyses on the risk of VTE in patients with PM and DM

| Primary Analysis (N= 443) HR (95%CI) |

Sensitivity Analysis 1 (N= 309) HR (95% CI) |

Sensitivity Analysis 2 (N= 443) HR (95% CI) |

Sensitivity Analysis 3 (N= 443) HR (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Prevalence = 10%a ORb = 1.3 |

Prevalence = 10%a ORb = 3.0 |

Prevalence = 20% a ORb = 1.3 |

Prevalence = 20% a ORb = 3.0 |

||||

|

| |||||||

| PM | |||||||

| VTE | 7.0 (3.34–14.64) | 11.01 (4.02–30.11) | 4.93 (2.58–9.45) | 7.03 (3.36–14.74) | 5.39 (2.52–11.57) | 6.92 (3.30–14.51) | 4.72 (2.20–10.12) |

| DVT | 6.16 (2.07–18.35) | 8.94 (2.14–37.39) | 4.03 (1.84–8.80) | 6.12 (2.04–18.34) | 4.69 (1.49–14.72) | 6.06 (2.02–18.19) | 3.89 (1.19–12.74) |

| PE | 7.23 (2.86–18.29) | 10.35 (2.92–36.67) | 4.95 (2.09–11.74) | 7.40 (2.89–18.98) | 4.79 (1.82–12.61) | 6.53 (2.62–16.30) | 5.46 (2.15–13.85) |

|

| |||||||

| DM | |||||||

| VTE | 8.39 (3.04–23.14) | 4.58 (1.50–14.02) | 5.98 (2.27–15.78) | 8.28 (2.97–23.05) | 6.51 (2.27–18.68) | 8.54 (3.09–23.58) | 7.36 (2.58–20.99) |

| DVT | 9.40 (2.88–30.68) | 4.39 (1.14–16.88) | 7.91 (2.34–26.71) | 9.02 (2.74–29.75) | 6.86 (1.89–24.94) | 9.47 (2.90–30.92) | 8.57 (2.56–28.68) |

| PE | 4.70 (0.85–25.98) | 3.11 (0.39–24.70) | 2.38 (0.62–9.07) | 4.67 (0.83–26.16) | 4.20 (0.77–22.89) | 4.26 (0.76–23.95) | 4.26 (0.71–25.45) |

DVT, Deep vein thrombosis; HR, Hazard ratio; OR, Odds ratio; PE, Pulmonary embolism; VTE, Venous thromboembolism

hypothetical prevalence of the unmeasured confounder

hypothetical level of association between the unmeasured confounder and the outcome

Sensitivity analysis 1: limited to PM/DM cases that received a prescription for oral glucocorticoids, antimalarials, methotrexate, and immunosuppressives during follow-up

Sensitivity analysis 2: accounting for the competing risk of death

Sensitivity analysis 3: accounting for unmeasured confounders

DISCUSSION

This is the first large general population-based study to assess the risk of VTE in patients with PM and DM. Risk of VTE was substantially higher in individuals with PM and DM when compared to the general population (six and eight times, respectively). The corresponding risk of DVT was six and nine times higher in the PM and DM cohorts. The increased risk of PE was statistically significant only in the PM cohort (seven times higher). Furthermore, risk of VTE and PE were highest during the first year for PM (25 and 38 times, respectively) and progressively attenuated over time. Similarly, cases with DM had the highest risk during the first two years after diagnosis.

Plausible mechanisms exist to explain the increased risk of VTE events in autoimmune inflammatory diseases. According to Virchow’s triad, there are three main precursors to venous thrombosis: venous stasis, increased coagulability of the blood, and damage to the vessel wall. (36) Inflammatory arthritic conditions may affect venous stasis by decreasing mobility. They may also increase coagulability of the blood through inflammation-associated mechanisms. (9) Inflammation and coagulation pathways are integrated by extensive crosstalk and a tendency to function in concert. (37) Inflammation modulates thrombotic responses by up-regulating pro-coagulants such as tissue factors, down-regulating natural anticoagulants such as Proteins C and S, and suppressing fibrinolysis, all of which lead to a hypercoagulable state. (16) Furthermore, inflammation can affect endothelial function in both arteries and veins, and several inflammatory disorders have been shown to lead to vessel wall damage. (9)

The biologic impact of inflammatory myopathies on the risk of VTE may be higher in the initial years after diagnosis due to uncontrolled inflammatory activity before the full benefit of corticosteroid and/or disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug therapy is achieved. The decline in risk after the first two years may result from reduced inflammatory activity as the condition becomes more stable with medication. Alternatively, the use of glucocorticoids themselves could be the driver of the increased risk of VTE. Though glucocorticoids help to control inflammation, adverse side-effects like coagulation abnormalities (38, 39) may in fact lead to an increased risk of VTE, as suggested by a recent general population-based study examining the association between glucocorticoid use and VTE. (40) However, it should also be noted that an increased risk of VTE has been observed in some inflammatory conditions like infection (41, 42) where glucocorticoids are not used. Thus we believe that the time-trends observed in the present study suggest a pathogenic role of inflammation on the risk of VTE. Further investigations into the potential effects of glucocorticoids on VTE risk in the PM/DM population are warranted.

The difference in risk between DM and PM may be explained by the different pathogenesis of the two diseases. DM is a humorally mediated microangiopathy where vascular damage seems to play a key role, while PM is a T-cell-mediated disorder with no or minimal involvement of the vascular bed.(43)

Several studies evaluating risk of VTE in other inflammatory conditions, including RA, SLE and scleroderma, have reported similar trends, supporting the proposed role of chronic inflammation in the pathogenesis of VTE.(9, 10) (19) (20, 44)

Three recent European studies have examined VTE related outcomes in selected autoimmune disorders, including inflammatory myopathies. Zoller et al. (19) found a three-fold overall risk of PE in patients with PM/DM, with a 16-fold increased risk during the first year of follow up. Ramagopalan et al. (20) found a three-fold increased risk of VTE after hospital admission for PM/DM in the entire population of England. In both studies, outpatient data was not available; therefore a selection bias is highly likely. Moreover, authors did not adjust for other risk factors including medication use. In addition, the English cohort was based on prevalent cases (survivor cases) rather than incident cases. In a Danish hospital-based study, Johannesdottir et al. (21) found a three-fold risk of VTE in individuals with PM/DM after matching for birth year, sex, and country of residence. However, after adjusting for classic VTE risk factors, other comorbidities, and medication use, this increased risk became non-significant.

We acknowledge the potential limitations inherent to observational studies using administrative data. While uncertainty around diagnostic accuracy cannot be completely ruled out, we used one of the strictest case definitions available for identifying PM and DM in an administrative database, using both diagnostic codes and prescription drug data. Validation studies of similar algorithms used to identify inflammatory myopathies showed a specificity of 96.4% and a sensitivity of 88.4%. (29) Outcomes, including VTE, DVT and PE, were also assessed using administrative data. Although privacy protection laws prevent access to medical records to confirm diagnoses, validation studies of claims-based diagnostic codes have shown good validity for these outcomes. A positive predictive value of 93% was reported in a study with similar context to our dataset. (45)

While our multivariable analysis adjusted for many factors known to influence risk of outcomes, certain relevant confounders may not have been available in our databases. For example, smoking and body mass index have both been shown to be risk factors for VTE. (46) Antiphospholipid syndrome (APLS) may also predispose to VTE; however, while the exact prevalence of APLS in DM and PM is not known, it is likely to be low given that to the best of our knowledge only seven cases have been reported in the literature. (47, 48) We performed a sensitivity analysis to adjust for the potential role of unmeasured confounders, and found that the point estimates remained statistically significant. Having said this, our results could still be affected by unknown unmeasured confounders, similar to other observational studies.

Despite these limitations, there are several notable strengths to this study. We used a large Canadian administrative database based on the entire BC population, therefore findings are likely generalizable to the population at large. We included only incident PM/DM cases, which protects our findings from bias introduced when using prevalent cases (“survivors cohort”). We adjusted for all relevant risk factors and pre-existing co-morbidities that were available in the administrative databases. We used one of the strictest case definitions available for administrative databases, using both diagnostic codes and prescription drug data in our sensitivity analyses and the results remained statistically significant.

Our findings have significant implications for patients and clinicians. Given the increased risk of VTE in individuals with inflammatory myopathies, and the high mortality associated with PE, our data suggest that patients with PM/DM may need to be considered for thromboprophylaxis, particularly in the early phase after diagnosis. Further research is needed to confirm our findings, to identify which individuals have the highest risk, and to test the role of anticoagulation therapy as a preventative strategy to avoid these potentially deadly outcomes.

In conclusion, this is the first general population-based study to demonstrate an increased risk of DVT and PE in patients with inflammatory myopathies, especially within the initial years of diagnosis. This calls for increased vigilance in monitoring VTE, a potentially preventable complication in individuals with inflammatory myopathies.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Kathryn Reimer for her editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding: Canadian Arthritis Network, The Arthritis Society of Canada, The British Columbia Lupus Society (Grant 10-SRP-IJD-01) and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) (grant MOP 125960). The funding sources had no role in design, conduct or reporting of the study or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics approval: No personal identifying information was made available as part of this study; procedures were in compliance with British Columbia’s Freedom of Information and Privacy Protection Act. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board.

Contributors: ECC contributed to data analysis/interpretation and drafted the manuscript. HKC and JAAZ secured the funding source and contributed to study conception/design, data analysis/interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. ECS contributed to data analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Bernatsky S, Joseph L, Pineau CA, Belisle P, Boivin JF, Banerjee D, et al. Estimating the prevalence of polymyositis and dermatomyositis from administrative data: age, sex and regional differences. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2009 Jul;68(7):1192–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.093161. Epub 2008/08/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avina-Zubieta JASEBS, Lehman AJ, Shojania K, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Adult Prevalence of Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases (SARDs) in British Columbia. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2011;63:S719. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernatsky S, Panopalis P, Pineau CA, Hudson M, St Pierre Y, Clarke AE. Healthcare costs of inflammatory myopathies. The Journal of rheumatology. 2011 May;38(5):885–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101083. Epub 2011/03/03. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marie I. Morbidity and mortality in adult polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Current rheumatology reports. 2012 Jun;14(3):275–85. doi: 10.1007/s11926-012-0249-3. Epub 2012/03/14. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Airio A, Kautiainen H, Hakala M. Prognosis and mortality of polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients. Clinical rheumatology. 2006 Mar;25(2):234–9. doi: 10.1007/s10067-005-1164-z. Epub 2006/02/16. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuo CF, See LC, Yu KH, Chou IJ, Chang HC, Chiou MJ, et al. Incidence, cancer risk and mortality of dermatomyositis and polymyositis in Taiwan: a nationwide population study. The British journal of dermatology. 2011 Dec;165(6):1273–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10595.x. Epub 2011/09/08. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avina-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, Etminan M, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2008 Dec 15;59(12):1690–7. doi: 10.1002/art.24092. Epub 2008/11/28. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avina-Zubieta JA, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, Lehman AJ, Lacaille D. Risk of incident cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012 Sep;71(9):1524–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200726. Epub 2012/03/20. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi HK, Rho YH, Zhu Y, Cea-Soriano L, Avina-Zubieta JA, Zhang Y. The risk of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis in rheumatoid arthritis: a UK population-based outpatient cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jul;72(7):1182–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Man A, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Dubreuil M, Rho YH, Peloquin C, et al. The risk of cardiovascular disease in systemic sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jul;72(7):1188–93. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szabo SM, Levy AR, Rao SR, Kirbach SE, Lacaille D, Cifaldi M, et al. Increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in individuals with ankylosing spondylitis: a population-based study. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2011 Nov;63(11):3294–304. doi: 10.1002/art.30581. Epub 2011/08/13. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yurkovich M, Vostretsova K, Chen W, Avina-Zubieta JA. Overall and cause-specific mortality in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis care & research. 2013 Sep 19; doi: 10.1002/acr.22173. Epub 2013/10/10. Eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMahon M, Hahn BH, Skaggs BJ. Systemic lupus erythematosus and cardiovascular disease: prediction and potential for therapeutic intervention. Expert review of clinical immunology. 2011 Mar;7(2):227–41. doi: 10.1586/eci.10.98. Epub 2011/03/24. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai YT, Dai YS, Yen MF, Chen LS, Chen HH, Cooper RG, et al. Dermatomyositis is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events: a Taiwanese population-based longitudinal follow-up study. The British journal of dermatology. 2013 May;168(5):1054–9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12245. Epub 2013/01/22. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tisseverasinghe A, Bernatsky S, Pineau CA. Arterial events in persons with dermatomyositis and polymyositis. The Journal of rheumatology. 2009 Sep;36(9):1943–6. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090061. Epub 2009/08/04. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu J, Lupu F, Esmon CT. Inflammation, innate immunity and blood coagulation. Hamostaseologie. 2010 Jan;30(1):5–6. 8–9. Epub 2010/02/18. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldhaber SZ. DVT Prevention: what is happening in the “real world”? Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 2003 Dec;29(Suppl 1):23–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45414. Epub 2004/01/20. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Cogo A, Cuppini S, Villalta S, Carta M, et al. The long-term clinical course of acute deep venous thrombosis. Annals of internal medicine. 1996 Jul 1;125(1):1–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-1-199607010-00001. Epub 1996/07/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zoller B, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Risk of pulmonary embolism in patients with autoimmune disorders: a nationwide follow-up study from Sweden. Lancet. 2012 Jan 21;379(9812):244–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61306-8. Epub 2011/11/29. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramagopalan SV, Wotton CJ, Handel AE, Yeates D, Goldacre MJ. Risk of venous thromboembolism in people admitted to hospital with selected immune-mediated diseases: record-linkage study. BMC medicine. 2011;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-1. Epub 2011/01/12. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johannesdottir SA, Schmidt M, Horvath-Puho E, Sorensen HT. Autoimmune skin and connective tissue diseases and risk of venous thromboembolism: a population-based case-control study. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2012 May;10(5):815–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04666.x. Epub 2012/02/23. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selva-O’Callaghan A, Fernandez-Luque A, Martinez-Gomez X, Labirua-Iturburu A, Vilardell-Tarres M. Venous thromboembolism in patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011 Sep-Oct;29(5):846–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naess IA, Christiansen SC, Romundstad P, Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Hammerstrom J. Incidence and mortality of venous thrombosis: a population-based study. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2007 Apr;5(4):692–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02450.x. Epub 2007/03/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solomon DH, Massarotti E, Garg R, Liu J, Canning C, Schneeweiss S. ASsociation between disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and diabetes risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;305(24):2525–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avina-Zubieta JA, Abrahamowicz M, De Vera MA, Choi HK, Sayre EC, Rahman MM, et al. Immediate and past cumulative effects of oral glucocorticoids on the risk of acute myocardial infarction in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2013 Jan;52(1):68–75. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes353. Epub 2012/11/30. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Etminan M, Forooghian F, Brophy JM, Bird ST, Maberley D. Oral fluoroquinolones and the risk of retinal detachment. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012 Apr 4;307(13):1414–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.383. Epub 2012/04/05. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Vera MA, Choi H, Abrahamowicz M, Kopec J, Goycochea-Robles MV, Lacaille D. Statin discontinuation and risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 70(6):1020–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.142455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aviña-Zubieta JACH, Abrahamowicz A, Rahman M, Sylvestre MP, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Risk of cerebrovascular disease associated with the use of glucocorticoids in patients with incident rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:990–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernatsky S, Linehan T, Hanly JG. The accuracy of administrative data diagnoses of systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases. The Journal of rheumatology. 2011 Aug;38(8):1612–6. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101149. Epub 2011/05/03. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huerta C, Johansson S, Wallander MA, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Risk factors and short-term mortality of venous thromboembolism diagnosed in the primary care setting in the United Kingdom. Archives of internal medicine. 2007 May 14;167(9):935–43. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.9.935. Epub 2007/05/16. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1993 Oct;46(10):1075–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. discussion 81–90. Epub 1993/10/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox D. Regression Models and Life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1972;34(2):187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Competing Risk Regression Models for Epidemiologic Data. Am J Epidemiol 2009. 2009 Jul 15;170(2):244–56. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneeweiss S. Sensitivity analysis and external adjustment for unmeasured confounders in epidemiologic database studies of therapeutics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety. 2006;15(5):291–303. doi: 10.1002/pds.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Virchow R. Gesammelte Abhandlungen zur wissenschaftlichen Medicin : mit 3 Tafeln und 45 Holzschnitten. Frankfurt a.M.: Meidinger; 1856. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zoller B, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Autoimmune diseases and venous thromboembolism: a review of the literature. American journal of cardiovascular disease. 2012;2(3):171–83. Epub 2012/09/01. eng. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sholter DE, Armstrong PW. Adverse effects of corticosteroids on the cardiovascular system. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2000 Apr;16(4):505–11. Epub 2000/04/29. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raynauld JP. Cardiovascular mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: how harmful are corticosteroids? The Journal of rheumatology. 1997 Mar;24(3):415–6. Epub 1997/03/01. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johannesdottir SA, Horvath-Puho E, Dekkers OM, Cannegieter SC, Jorgensen JO, Ehrenstein V, et al. Use of glucocorticoids and risk of venous thromboembolism: a nationwide population-based case-control study. JAMA internal medicine. 2013 May 13;173(9):743–52. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.122. Epub 2013/04/03. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smeeth L, Cook C, Thomas S, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Vallance P. Risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after acute infection in a community setting. Lancet. 2006 Apr 1;367(9516):1075–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alikhan R, Cohen AT, Combe S, Samama MM, Desjardins L, Eldor A, et al. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with acute medical illness: analysis of the MEDENOX Study. Arch Intern Med. 2004 May 10;164(9):963–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dalakas MC, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003 Sep 20;362(9388):971–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aviña-Zubieta JALD, Sayre EC, Esdaile J. Arthritis Rheum. 2013. The risk of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in systemic lupus erythematosus: a population-based cohort study. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willey VJ, Bullano MF, Hauch O, Reynolds M, Wygant G, Hoffman L, et al. Management patterns and outcomes of patients with venous thromboembolism in the usual community practice setting. Clinical therapeutics. 2004 Jul;26(7):1149–59. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90187-7. Epub 2004/09/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holst AG, Jensen G, Prescott E. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism: results from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circulation. 2010 May 4;121(17):1896–903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.921460. Epub 2010/04/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Souza FH, Levy-Neto M, Shinjo SK. Antiphospholipid syndrome and dermatomyositis/polymyositis: a rare association. Revista brasileira de reumatologia. 2012 Aug;52(4):642–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sherer Y, Livneh A, Levy Y, Shoenfeld Y, Langevitz P. Dermatomyositis and polymyositis associated with the antiphospholipid syndrome-a novel overlap syndrome. Lupus. 2000;9(1):42–6. doi: 10.1177/096120330000900108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]