Abstract

Objective

Excess mortality in RA is expected to have improved over time, due to improved treatment. Our objective was to evaluate secular five-year mortality trends in RA relative to general population controls in incident RA cohorts diagnosed in 1996–2000 vs. 2001–2006.

Methods

We conducted a population-based cohort study, using administrative health data, of all incident RA cases in British Columbia who first met RA criteria between 01/1996–12/2006, with general population controls matched 1:1 on gender, birth and index years. Cohorts were divided into earlier (RA onset 1996–2000) and later (2001–2006) cohorts. Physician visits and vital statistics data were obtained until Dec 2010. Follow-up was censored at 5 years to ensure equal follow-up in both cohorts. Mortality rates, mortality rate ratios, and hazard ratios (HRs) for mortality (RA vs. controls) using proportional hazard models adjusting for age, were calculated. Differences in mortality in RA vs. controls between earlier and later incident cohorts were tested via interaction between RA status (case/control) and cohort (earlier/later).

Results

24,914 RA cases and controls experienced 2747 and 2332 deaths, respectively. Mortality risk in RA vs. controls differed across incident cohorts for all-cause, CVD and cancer mortality (interactions p<0.01). A significant increase in mortality in RA vs. controls was observed in earlier, but not later, cohorts [all-cause mortality aHR(95%CI):1.40(1.30;1.51) and 0.97(0.89;1.05), respectively].

Conclusion

In our population-based incident RA cohort, mortality compared to the general population improved over time. Increased mortality in the first five years was observed in people with RA onset before, but not after, 2000.

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, mortality, epidemiology, administrative health data

INTRODUCTION

Since the 1950’s, studies have drawn attention to the premature mortality in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) compared to the general population [1–7]. Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the leading cause of excess mortality; infections and malignancies are other causes [8–15]. Mortality risk is generally lower in incident than prevalent cohorts [2, 4, 5, 8], as reflected by a lower SMR (1.2 vs.1.9, respectively) [16]. Studies evaluating mortality in the early years of RA report mixed results [7]. Some cohorts from early arthritis clinics, with early/aggressive DMARD treatment, report no excess mortality [17–19]; while others report increased mortality apparent from early years of disease and increasing with RA duration [20–22]. Others report mortality becoming apparent after 7–10 years [23].

Increased mortality in RA is believed to be a consequence of inflammation, as markers of inflammation and disease severity have been associated with increased risk of death [24–31]. With more effective treatments and a paradigm shift in treating RA aimed at achieving remission, mortality would be expected to have improved over time [32–37]. Previous studies evaluating secular trends in RA mortality, including a meta-analysis [4], have generally found no improvement relative to the general population, with some studies suggesting a widening mortality gap, due to improved mortality in the general population but not, or to a lesser extent, in RA [4, 16, 23, 38–43]. However, these studies evaluated cohorts with RA onset up to the 1990s. In contrast, our study evaluates temporal trends in more contemporary incident cohorts with RA onset before vs. after 2000, a period when RA treatment changed drastically [32, 44–47] and awareness of cardiovascular risk in RA, and its link to inflammation, increased [24, 28, 29, 48–53].

The objective of our study was to evaluate secular trends in RA mortality, by assessing whether the mortality risk over the first five years of RA, compared to general population controls, differed between incident RA cases diagnosed in 1996–2000 and in 2001–2006.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a longitudinal study of a population-based incident RA cohort with matched controls from the general population, using administrative health data from the entire province of British Columbia, Canada.

Cohort definition

Incident RA cohort

All incident RA cases in British Columbia who first met criteria for RA between 01-1996 and 03-2006 (using data from 01-1990 onwards) were identified, using physician billing data from the Ministry of Health in a universal health care system, and were followed until 12-2010. Using previously published criteria [54], individuals were identified as RA cases if they had at least two physician visits at least two months apart within a five year period with an ICD9 code for rheumatoid arthritis (714.X) [55]. To improve specificity, individuals were excluded if they had at least two subsequent visits with ICD9 codes for other forms of inflammatory arthritis (SLE, other connective tissue diseases, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthropathies). Cases were also excluded if a diagnosis of RA by a non-rheumatologist was never confirmed when the individual saw a rheumatologist; or if they had no subsequent RA diagnosis over more than five years of follow-up. These criteria have been validated in a subsample who participated in an RA survey. Using opinion of an independent rheumatologist reviewing medical records from their treating physicians as gold standard, we estimated the positive predictive value at 0.82 [56].

General Population Controls with no diagnoses of inflammatory arthritis were selected, using the same administrative databases as for the RA cohort, matching controls to RA cases in a 1:1 ratio on gender, birth year, and index year.

The sample was divided into two cohorts: an earlier and later cohort (cases with RA onset in 1996–2000 vs. 2001–2006, respectively, and their controls).

Data Sources

Data were obtained from administrative databases of the Ministry of Health of British Columbia on all provincially funded health care services used since 01-1990, including all physician visits, with one diagnostic code representing the reason for the visit, from the Medical Service Plan database [57]; as well as hospital discharge data [58]. Vitals statistics data [59] were obtained, from 01-1996 onwards, on deaths and primary cause of death derived from death certificates. All data were available until December 2010. Several population-based studies have been published using these data [54, 60–66].

Ethics

No personal identifying information was provided. All procedures were compliant with BC’s Freedom of Information and Privacy Protection Act. The study received ethics approval from University of British Columbia.

Statistical analyses

Person-years of follow-up were calculated for incident RA cases and controls, from index date to end of follow-up (censored at 5 years to ensure equal follow-up in earlier and later cohorts), last health care utilization, or death. Index date was defined, for RA cases, as when they met incident RA inclusion criteria; and, for controls, as the date of a randomly selected health care encounter occurring in the same calendar year as the index year of their matched case. Mortality rates from all-cause, CVD, malignancy and infections, were calculated for RA cases and controls, along with mortality rate ratios, with 95% confidence intervals (CI), representing the risk of mortality in RA relative to controls. We also used a parametric exponential proportional hazards (PH) model to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) representing the mortality risk in RA compared to controls, adjusted for age. Analyses adjusted for comorbidities which differed at baseline between RA and controls, and for the Romano modification of the Charlson comorbidity score (with RA excluded from comorbidities) [67–69] were also performed. To test if differences in excess risk of mortality (in RA relative to controls) changed over time, we tested the interaction between the indicators of RA (case vs. control) and incident cohort (earlier vs. later), in the exponential PH model. A statistically significant interaction indicates that the mortality risk in RA relative to the general population differs between the earlier and later cohorts.

Kaplan Meier survival curves were estimated, describing survival from index date until death, stratified according to RA status, for all-cause and cause-specific mortality, censoring at five years of follow-up, last health care utilization, or death from other cause (for cause-specific analyses). Separate analyses were conducted for 1996–2000 and 2001–2006 cohorts. Sensitivity analyses estimated survival curves using all available follow-up time (i.e., not censoring at 5 years). Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

The sample included 24,914 RA individuals and 24,914 general population controls. Using BC population estimates, our cohorts yield age and sex standardized incidence rates of 58 per 100,000 for the 1996–2000 cohort and 68 per 100,000 for the 2001–2006 cohort, consistent with reported RA incidence rates [70, 71]. During the first five years 2,747 deaths were observed in the RA cohort and 2,332 in controls.

Baseline characteristics of the RA cohorts and controls, measured at index date, are described in Table 1. RA cases had more comorbidities than controls (higher rates of prior CVD, COPD, hospitalized infections, hospitalization rate), but no difference in overall comorbidity score (Romano score with RA excluded from comorbidities) [67–69]. Of note, age at index date was slightly lower in the later than earlier RA cohort, although the difference is not clinically meaningful (mean [SD]: 57.49[12.8] and 58.35[12.9] years, respectively). Furthermore, our analyses are age adjusted.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of RA cases and controls in the earlier (incidence 1996–2000) and later (incidence 2001–06) cohorts.

| Characteristic | Controls 1996–2000 Cohort (n=10,798) | RA 1996–2000 Cohort (n=10,798) | RA vs. controls p-value | Controls 2001–06 Cohort (n=14,116) | RA 2001–06 Cohort (n=14,116) | RA vs. controls p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 7162 (66.33) | 7162 (66.33) | 1.000 | 9398 (66.58) | 9398 (66.58) | 1.000 |

| Age at index date | 58.34 (17.39) | 58.35 (17.38) | 0.983 | 57.49 (16.88) | 57.49 (16.88) | 0.978 |

| RA duration at index dateπ, yrs, median (25Q;75Q) | N/A | 0.63 (0.27;2.35) | N/A | 0.36 (0.23;0.90) | ||

| Romano Charlson comorbidity score*1 | 0.36 (1.07) | 0.38 (0.98) | 0.200 | 0.36 (1.08) | 0.37 (0.96) | 0.215 |

| Hospitalization rate per year§2 | 0.22 (0.34) | 0.28 (0.40) | <.001 | 0.19 (0.29) | 0.23 (0.31) | <.001 |

| Cumulative no. of hospitalized days§2 | 14.59 (78.08) | 14.36 (51.12) | 0.794 | 12.47 (62.77) | 12.66 (29.22) | 0.744 |

| Diabetes1, n (%) | 605 (5.60) | 586 (5.43) | 0.571 | 956 (6.77) | 907 (6.43) | 0.240 |

| COPD1, n (%) | 668 (6.19) | 813 (7.53) | <.001 | 718 (5.09) | 940 (6.66) | <.001 |

| Renal failure1, n (%) | 72 (0.67) | 78 (0.72) | 0.623 | 144 (1.02) | 145 (1.03) | 0.953 |

| Any CVD1, n (%) | 4115 (38.11) | 4392 (40.67) | <.001 | 5724 (40.55) | 6115 (43.32) | <.001 |

| Prior CVA2, n (%) | 754 (6.98) | 831 (7.70) | 0.045 | 1053 (7.46) | 991 (7.02) | 0.154 |

| Prior AMI2, n (%) | 536 (4.96) | 548 (5.08) | 0.708 | 698 (4.94) | 721 (5.11) | 0.531 |

| Prior cancer2, n (%) | 1378 (12.76) | 1391 (12.88) | 0.791 | 2036 (14.42) | 2078 (14.72) | 0.479 |

| Prior hospitalized infection2, n (%) | 839 (7.77) | 1094 (10.13) | <.001 | 1181 (8.37) | 1531 (10.85) | <.001 |

Assessed over one year prior to index date;

Assessed over all available data pre-index date, ie from 1990 onwards

RA duration at index date was calculated as time from first RA visit to index date (i.e. second RA visit at least 8 weeks later).

Romano Charlson refers to the Romano adaptation of the Charlson co-morbidity score developed for use with administrative health data, excluding RA as a comorbidity [67–69].

Hospitalization rate was calculated as the number of hospitalization events per year; Cumulative number of hospitalized days was calculated as the sum of all days spent in hospital during all hospitalizations.

Unless otherwise indicated, values represent Mean (SD); p-values are from chi-square for binary variables, or two-sample t-test for continuous variables.

Abbreviations: 25Q;75Q = 25th and 75th percentile; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; AMI: acute myocardial infarct; CVD: any cardiovascular disease.

Mortality rates, and mortality risk in RA relative to general population controls, are shown in Table 2. In the entire cohort, mortality rates of 24.43 and 20.72 per 1000 person-years were observed in RA and controls, respectively, yielding an all-cause mortality rate ratio of 1.18 (95%CI: 1.12;1.25). Greater mortality in RA compared to controls were observed for mortality from CVD and infections.

Table 2.

Mortality Risk in RA compared to general population controls

| Mortality rate RA (per 1000 PY) | Mortality rate controls (per 1000 PY) | Mortality rate ratio (95% CI) RA vs. controls |

aHR* (95% CI) RA vs. controls |

aHRΩ (95% CI) RA vs. controls |

aHR§ (95% CI) RA vs. controls |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Entire cohort, | ||||||

| All-cause mortality | 24.43 | 20.72 | 1.18 (1.12, 1.25) | 1.17 (1.11, 1.24) | 1.14 (1.08, 1.20) | 1.15 (1.09, 1.22) |

| mortality from CVD | 8.49 | 7.04 | 1.21 (1.10, 1.33) | 1.20 (1.09, 1.31) | 1.16 (1.05, 1.27) | 1.19 (1.08, 1.32) |

| mortality from cancer | 6.48 | 6.20 | 1.05 (0.94, 1.16) | 1.04 (0.94, 1.15) | 1.04 (0.94, 1.16) | 1.02 (0.92, 1.14) |

| mortality from infection | 1.45 | 0.91 | 1.58 (1.23, 2.05) | 1.57 (1.23, 2.01) | 1.51 (1.18, 1.94) | 1.50 (1.15, 1.95) |

|

| ||||||

| All-cause mortality: | ||||||

| Incident cohort 1996–2000 | 32.68 | 23.45 | 1.39 (1.29, 1.51) | 1.40 (1.30, 1.51) | 1.34 (1.24, 1.45) | 1.38 (1.27, 1.49) |

| Incident cohort 2001–2006 | 18.29 | 18.59 | 0.98 (0.91, 1.07) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.05) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.03) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.04) |

|

| ||||||

| Mortality from CVD | ||||||

| Incident cohort 1996–2000 | 12.30 | 8.50 | 1.45 (1.27, 1.64) | 1.45 (1.28, 1.65) | 1.39 (1.23, 1.58) | 1.45 (1.27, 1.65) |

| Incident cohort 2001–2006 | 5.66 | 5.90 | 0.96 (0.83, 1.11) | 0.94 (0.81, 1.08) | 0.93 (0.80, 1.07) | 0.94 (0.81, 1.09) |

|

| ||||||

| Mortality from cancer | ||||||

| Incident cohort 1996–2000 | 8.61 | 7.08 | 1.22 (1.05, 1.41) | 1.22 (1.06, 1.41) | 1.22 (1.06, 1.41) | 1.20 (1.03, 1.40) |

| Incident cohort 2001–2006 | 4.90 | 5.52 | 0.89 (0.76, 1.04) | 0.88 (0.75, 1.02) | 0.89 (0.76, 1.03) | 0.86 (0.74, 1.01) |

|

| ||||||

| Mortality from infections | [0.097] | [0.142] | [0.104] | |||

| Incident cohort 1996–2000 | 1.88 | 0.97 | 1.93 (1.34, 2.79) | 1.94 (1.37, 2.75) | 1.82 (1.28, 2.59) | 1.86 (1.28, 2.70) |

| Incident cohort 2001–2006 | 1.13 | 0.87 | 1.30 (0.91, 1.88) | 1.27 (0.90, 1.81) | 1.26 (0.89, 1.78) | 1.20 (0.83, 1.75) |

Abbreviations: RA= rheumatoid arthritis; CI= confidence intervals; CVD = cardiovascular diseases; aHR= adjusted hazard ratio

aHR adjusted for age at index date.

aHR adjusted for age at index date, plus baseline CVD, COPD, infection, hospitalizations per year, and Romano modification of Charlson score excluding RA from list of comorbidities.

aHR adjusted for age at index date; results from sensitivity analysis excluding all cases/controls with <6 years of enrollment in the Medical Service Plan (MSP) at index date.

When comparing mortality risk in RA relative to controls, across incident cohorts, we observed important differences between the 1996–2000 and 2001–2006 cohorts. A 39% increase in all-cause mortality was observed in the earlier RA cohort relative to the general population; whereas no increase was observed in the later cohort. Similarly, increased mortality was observed in earlier, but not later, RA cohorts relative to controls for deaths from CVD, cancer and infections. These time-differences in excess mortality were confirmed in age-adjusted exponential models, where significant interactions between RA (vs. controls) and incident cohort (earlier vs. later) were found for mortality from all-causes (p<0.001), CVD (p<0.001) and cancer (p=0.002), but not from infection (p=0.097).

To confirm our findings, we assessed age at death. Despite being matched on age to general population controls, RA cases in the earlier cohort died, on average, 1.3 years earlier than controls [mean(SD) age at death from all causes: 76.7(12.9) versus 78.0(11.0) years in controls]; but not in the later cohort [77.3(12.8) vs. 77.8(11.4) years in controls].

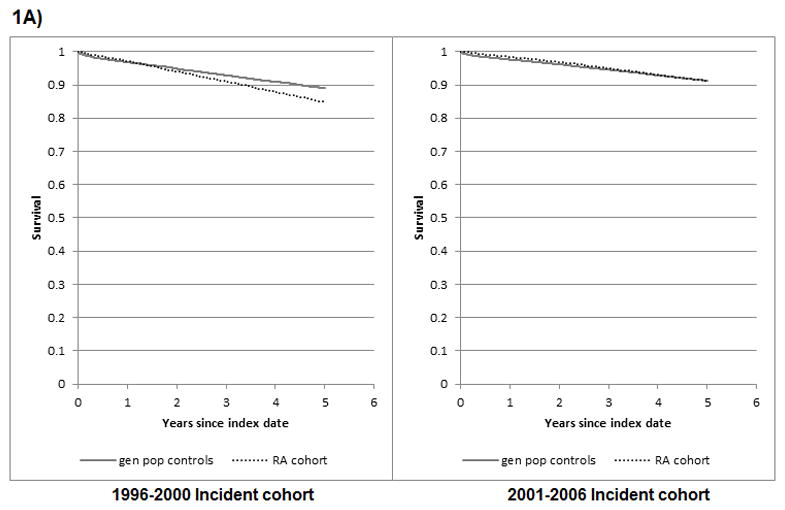

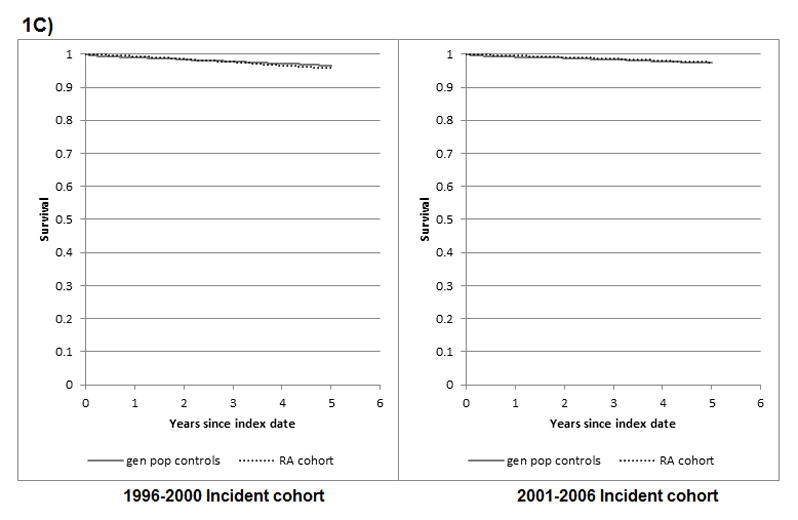

Similarly, Kaplan Meier (KM) curves revealed lower survival in RA cases than in general population controls for death from all-causes, CVD, and cancer, in the earlier cohort (log rank test p value < 0.01), but not the later cohort (p = 0.695, 0.583, 0.127, respectively) (Figure 1). Of note, KM analyses require cautious interpretation as they are unadjusted and based on relatively few cause-specific mortality events. Too few deaths from infections were observed to allow adequate interpretation of results. KM results were similar when survival was uncensored (log rank test p value ≤ 0.01 for mortality from all cause, CVD and cancer in earlier cohort; and p = 0.210, 0.510 and 0.473, respectively, for the later cohort with up to 8 years of follow-up) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1. Survival from all-causes, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and infection, in RA and general population controls.

1A) All-cause mortality

log rank test comparing KM survival in RA vs controls for 1996–2000 cohort: p < 0.001; and for the 2001–2006 cohort: p = 0.695

1B) Mortality from cardiovascular diseases

log rank test comparing KM survival in RA vs controls for 1996–2000 cohort: p < 0.001; and for the 2001–2006 cohort: p = 0.583

1C) Mortality from cancer

log rank test comparing KM survival in RA vs controls for 1996–2000 cohort: p = 0.007; and for the 2001–2006 cohort: p = 0.127

Robustness of our results were tested in sensitivity analyses. Because individuals moving to BC could appear to be incident cases, we excluded all cases/controls with <6 years of MSP enrollment at index date. This yielded similar results (Table 2). Because the lead-in time to differentiate incident from prevalent RA was longer for the 2001–2006 cohort (11 vs. 6 years), we limited the 2001–2006 cohort’s lead-in time to 6 years. Results did not differ (all-cause mortality rate ratio: 0.96[0.89;1.04] vs. 0.98[0.91;1.07]). To ensure baseline differences in RA duration across the two cohorts didn’t confound the interaction [72], we adjusted the exponential PH models for RA duration at index date. To avoid near-collinearity between RA/control status and RA duration (which, by definition, equals 0 for all controls), RA duration in RA cases was centered to a mean of 0 [73]. Results were similar [all-cause mortality aHR 1.48(1.37;1.60) for earlier and 0.92(0.85;1.00) for later cohorts] and the interaction remained significant (p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

We conducted a population-based study of a large incident RA cohort with general population controls, using administrative health data in a universal health care system, to evaluate RA mortality trends over time. Our study reveals that the risk of death in RA compared to the general population has improved over time. Statistically significant improvement was observed for all-cause mortality, as well as deaths from cardiovascular diseases, and cancer, but not from infections. In our cohort, over 5 years of follow-up, an increased risk of mortality in RA compared to the general population was observed in people with RA onset on or before 2000, but not in people with RA onset after 2000. Although improvement in mortality risk was clearly observed in our study, one should be cautious about interpreting our results as indicating that mortality differences between RA and the general population no longer exist, as five years of follow-up is relatively short, and it is possible that differences between RA and the general population would be observed with longer follow-up, especially since previous studies have suggested that the greatest increase in mortality risk may occur after 7–10 years of disease [23]. Of note, in sensitivity analyses, KM survival curves estimated using all available follow-up (up to eight years for the later cohort) yielded similar results.

Strengths of our study include the population-based nature of our cohort with complete capture of all RA cases in the province of British Columbia, ensuring the sample is representative of the entire spectrum of RA disease and of patients treated in everyday clinical practice; the inclusion of incident cases with complete follow-up from RA onset to death or study end; and, the large sample size providing adequate power to look at rare events such as mortality.

Limitations of our study are those inherent to observational studies and studies using administrative data. They include uncertainty around RA diagnosis identified using administrative data and possible effect of unmeasured confounding. Measuring the timing of RA onset is imprecise with administrative data. For these to influence the observed difference in mortality risk between the earlier and later cohorts, they would have to differentially affect both cohorts.. Temporal differences in billing code practices during the pre-diagnosis phase could influence timing of the index date. Temporal differences in accuracy of billing data could influence the number of “true/false” RA cases included. However, over the period examined, one would expect improved accuracy as a result, for example, of the introduction of electronic medical records. This would constitute a conservative bias as less non-RA cases would be included in the later cohort. We observed a small increase in RA incidence rate over 1996–2006. A similar trend was reported in Olmsted County over the same period [74]. Nonetheless, inclusion of a greater number of non-RA cases in the later cohort could bias results towards a reduced mortality difference with the general population.

Survival could appear improved in the later incident cohort if RA was diagnosed earlier, or if people presented to care earlier, as a result of more recent efforts to raise awareness about the importance of early RA diagnosis and treatment. Of note, median RA duration at index date was slightly shorter (3 months) in the 2001–2006 than the 1996–2000 cohort; and mean age at index date was only slightly lower in the later cohort (57.5 years vs 58.4 in the earlier cohort). Furthermore, a younger age at death in RA relative to controls, was observed in the earlier, but not the later, cohort, suggesting the difference in mortality is not due to earlier detection.

It is also possible that incident cohorts are contaminated with prevalent cases. Given our minimum lead-in period of 6 years, this would require gaps between consecutive RA visits longer than 6 years. In our cohort, this occurred very infrequently (only 0.44% of periods between consecutive RA visits were > 6 yrs; 94.3 % were <1 year; 97.3% <2 years). Because of potential differential effect on the two cohorts (with less prevalent cases in the 2001–2006 cohort due to longer lead-in time), we performed sensitivity analyses limiting the lead-in time of the 2001–2006 cohort to 6 years, which yielded similar results. Prevalent RA cases moving to BC during the study period could also be included. However, this would likely not differentially affect the two cohorts, and sensitivity analyses excluding individuals registered <6 years prior to index date yielded similar results.

Two other recent studies, until now published only in abstract form, also support the concept that the mortality risk in RA compared to the general population has recently improved [75, 76]. A population-based study of Olmsted County, US, found a significant reduction in cardiovascular mortality among patients with RA onset in 2000–2007vs. 1990–1999 (HR:0.43, 95% CI:0.19;0.94) [75], with no difference with the general population for the 2000–2007 patients. However, their results are based on a small sample (315 RA patients in 2000–2007 cohort), and only 8 deaths observed in RA and 9 in controls. Our analyses provide more robust confirmation of these findings in an independent, much larger sample, with more than 2000 deaths in RA and controls. Interestingly, previous studies from the same group described a gradual widening of the mortality gap, relative to the general population, for RA patients with more recent onset over 1955 to 2000 [38, 39]. This suggests that improvement in mortality may be limited to patients with RA onset after 2000, as observed in our study. The second study used an electronic medical record database in the UK to compare all-cause mortality in two incident RA cohorts (RA onset 1999–2005 followed until end of 2005; and RA onset 2006–2012 followed until end of 2012) compared to general population controls [76]. Consistent with our findings, they found a significant reduction in the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality, relative to controls, for the later RA cohort (p=0.027 for interaction). However, even in the later cohort, RA mortality remained increased compared to the general population (HR 1.21, 95%CI:1.05;1.39).

Our findings have important implications for people living with arthritis, clinicians and health policy makers. It provides reassuring evidence suggesting that time trends in the disease itself and/or its management are having a beneficial impact on an outcome of utmost importance to people living with arthritis. Exploring why mortality has improved over time is beyond the scope of this study. We speculate that it may be due to improved RA treatment, with more effective control of inflammation, from availability of more effective DMARDs and from the paradigm shift in RA management towards early, aggressive treatment with the aim of eradicating inflammation. Alternatively, improved survival could be due to improved prevention, detection or management of life-threatening comorbidities, such as cardiovascular diseases, as a result of increased awareness of its role as a leading cause of premature death. It is also possible that the natural history of RA has evolved over time. Exploration of these reasons warrants further study. Furthermore, future longer-term studies should compare mortality in RA versus general population over > 10 years of follow-up, since RA onset.

In conclusion, in our population-based incident RA cohort, the five-year mortality risk compared to the general population, has improved for patients with RA onset in the 21st century. Statistically significant relative risk reductions were observed for all-cause mortality, as well as deaths from cardiovascular diseases, and cancer, but not from infections. In our cohort, during the first 5 years after RA diagnosis, the mortality gap between RA and the general population observed in people with RA onset on or before 2000, was not observed for people with RA onset after 2000. Longer follow-up is needed before concluding that mortality differences between RA and the general population no longer exist.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Survival from all-causes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer in RA and general population controls, calculated without censoring follow-up at 5 years

Acknowledgments

FUNDING.

We would like to thank the Ministry of Health of British Columbia and Population Data BC for providing access to the administrative data. All inferences, opinions, and conclusions drawn in this publication are those of the authors, and do not reflect the opinions or policies of the Data Stewards. This study was funded by the Canadian Institute for Health Research (#32615), who played no role in the design or conduct of the study, other than providing peer-review of the study proposal.

References

- 1.Cobb S, Anderson F, Bauer W. Length of life and cause of death in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1953;249:553–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195310012491402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naz SM, Symmons DPM. Mortality in established rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:871–83. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabriel SE. Why do persons with rheumatoid arthritis still die prematurely? Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(Suppl 3):iii30–iii34. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.098038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dadoun Z-KN, Combescure C, Elhai M, Rozenberg S, Gossec L, Fautrel B. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis over the last fifty years: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine. 2013;80:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myasoedova E, Davis JM, III, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE. Epidemiology of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Rheumatoid Arthritis and Mortality. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12:379–85. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0117-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sokka T, Abelson B, Pincus T. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: 2008 update. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:S35–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmona L, Cross M, Williams B, Lassere M, March L. Rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24(6):733–745. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aviña-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, Etminan M, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1690–7. doi: 10.1002/art.24092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sihvonen S, Korpela M, Laippala P, Mustonen J, Pasternack A. Death rates and causes of death in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:221–7. doi: 10.1080/03009740410005845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vandenbroucke JP, Hazevoet HM, Cats A. Survival and cause of death in rheumatoid arthritis: a 25-year prospective followup. J Rheumatol. 1984;11:158–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallberg-Jonsson S, Ohman ML, Dahlqvist SR. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis in Northern Sweden. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:445–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell DM, Spitz PW, Young DY, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF. Survival, prognosis, and causes of death in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:706. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mutru O, Laakso M, Isomäki H, Koota K. Ten Year Mortality And Causes Of Death In Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;290:1797–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6484.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myllykangas-Luosujärvi R, Aho K, Kautiainen H, Isomäki H. Shortening of life span and causes of excess mortality in a population-based series of subjects with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1995;13:149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prior P, Symmons DP, Scott DL, Brown R, Hawkins CF. Cause of death in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1984;23:92–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/23.2.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward MM. Recent improvements in survival in patients with RA: better outcomes or different study designs? Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(6):1467–1469. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1467::AID-ART243>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindqvist E, Eberhardt K. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis patients with disease onset in the 1980s. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58(1):11–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroot EJ, Van Leeuwen MA, Van Rijswijk MH, Prevoo ML, Van’t Hof MA, Van de Putte LB, et al. No increased mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: up to 10 years of follow up from disease onset. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(12):954–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.12.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peltomaa R, Paimela L, Kautiainen H, Leirisalo-Repo M. Mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated actively from the time of diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(10):889–94. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.10.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodson NJ, Wiles NJ, Lunt M, Barrett EM, Silman AJ, Symmons DP. Mortality in early inflammatory polyarthritis: cardiovascular mortality is increased in seropositive patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(8):2010–9. doi: 10.1002/art.10419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodson N, Marks J, Lunt M, Symmons D. Cardiovascular admissions and mortality in an inception cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with onset in the 1980s and 1990s. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(11):1595–601. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.034777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young A, Koduri G, Batley M, Kulinskaya E, Gough A, Norton S, et al. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Increased in the early course of disease, in ischaemic heart disease and in pulmonary fibrosis. Rheumatol. 2007;46(2):350–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radovits BJ, Fransen J, Al Shamma S, Eijsbouts AM, van Riel PL, Laan RF. Excess mortality emerges after 10 years in an inception cohort of early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:362–70. doi: 10.1002/acr.20105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wållberg-Jonsson S, Johansson H, Ohman ML, Rantapää-Dahlqvist S. Extent of inflammation predicts cardiovascular disease and overall mortality in seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. A retrospective cohort study from disease onset. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2562–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corbett M, Dalton S, Young A, Silman A, Shipley M. Factors predicting death, survival and functional outcome in a prospective study of early rheumatoid disease over fifteen years. Rheumatol. 1993;32:717–23. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.8.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erhardt CC, Mumford PA, Venables PJ, Maini RN. Factors predicting a poor life prognosis in rheumatoid arthritis: an eight year prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48:7–13. doi: 10.1136/ard.48.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pincus T, Brooks RH, Callahan LF. Prediction of long-term mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis according to simple questionnaire and joint count measures. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:26–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-1-199401010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Pineiro A, Garcia-Porrua C, Testa A, Llorca J. High-grade C-reactive protein elevation correlates with accelerated atherogenesis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1219–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Lopez-Diaz MJ, Pineiro A, Garcia-Porrua C, Miranda-Filloy JA, et al. HLA-DRB1 and persistent chronic inflammation contribute to cardiovascular events and cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:125–32. doi: 10.1002/art.22482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navarro-Cano G, Del Rincón I, Pogosian S, Roldán JF, Escalante A. Association of mortality with disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis, independent of comorbidity. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2425–33. doi: 10.1002/art.11127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Gefeller O, Choi HK. Predicting mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1530–42. doi: 10.1002/art.11024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Koeller M, Weisman MH, Emery P. New therapies for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2007;370:1861–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60784-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strand V, Singh JA. Improved health-related quality of life with effective disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: evidence from randomized controlled trials. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(Suppl 9):S237–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Curtis JR, Singh JA. Use of biologics in rheumatoid arthritis: current and emerging paradigms of care. Clin Ther. 2011;33:679–707. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, Curtis JR, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:762–84. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bykerk VP, Akhavan P, Hazlewood GS, Schieir O, Dooley A, Haraoui B, et al. Canadian Rheumatology Association recommendations for pharmacological management of rheumatoid arthritis with traditional and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1559–82. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Doran MF, Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, et al. Survival in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based analysis of trends over 40 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:54–8. doi: 10.1002/art.10705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalez A, Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Davis rJM, Therneau TM, et al. The widening mortality gap between rheumatoid arthritis patients and the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3583–7. doi: 10.1002/art.22979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergström U, Jacobsson LTH, Turesson C, Sektionen för AMK, et al. Internal Medicine Research U, Institutionen för kliniska vetenskaper M. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality remain similar in two cohorts of patients with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis seen in 1978 and 1995 in Malmö, Sweden. Rheumatol (Oxford, England) 2009;48:1600–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Humphreys JH, Warner A, Chipping J, Marshall T, Lunt M, Symmons DPM, et al. Mortality Trends in Patients With Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Over 20 Years: Results From the Norfolk Arthritis Register. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1296–301. doi: 10.1002/acr.22296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Björnådal L, Baecklund E, Yin L, Granath F, Klareskog L, Ekbom A, et al. Decreasing mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthrithis: results from large population based cohort in Sweden 1964–95. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:906–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ziade N, Jougla E, Coste J. Population-level influence of rheumatoid arthritis on mortality and recent trends: a multiple cause-of-death analysis in France, 1970–2002. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1950–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pincus T, O’Dell JKJ. Combination therapy with multiple DMARDs in RA: a preventive strategy. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:768–774. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-10-199911160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fries JF. Current treatment paradigms in RA. Rheumatol(Oxford) 2000;39(suppl 1):30–35. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.rheumatology.a031492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wollheim FA. Approaches to RA in 2000. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:193–201. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on clinical guidelines. Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 Update. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(2):328–346. doi: 10.1002/art.10148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Doornum S, McColl G, Wicks IP. Accelerated atherosclerosis: an extraarticular feature of rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:862–73. doi: 10.1002/art.10089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.del Rincon ID, Williams K, Stern MP, Freeman GL, Escalante A. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2737–45. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2737::AID-ART460>3.0.CO;2-%23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodson NJ, Wiles NJ, Lunt M, Barrett EM, Silman AJ, Symmons DP. Mortality in Early Inflammatory Polyarthritis. Cardiovascular mortality is increased in seropositive patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(8):2010–2019. doi: 10.1002/art.10419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Martin J. Rheumatoid arthritis: a disease associated with accelerated atherogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;35:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sattar N, McCarey DW, Capell H, McInnes IB. Explaining how “high-grade” systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2003;108:2957–63. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099844.31524.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Leuven SI, Franssen R, Kastelein JJ, Levi M, Stroes ES, Tak PP. Systemic inflammation as a risk factor for atherothrombosis. Rheumatol (Oxford) 2008;47:3–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lacaille D, Anis AH, Guh DP, Esdaile JM. Gaps in care for rheumatoid arthritis: a population study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:241–8. doi: 10.1002/art.21077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacLean CH, Louie R, Leake B, et al. Quality of care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 2000;284(8):984–992. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.8.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang J, Rogers P, Lacaille D. Can American College of Rheumatology criteria for Rheumatoid Arthritis be assessed using self-report data? – Comparison of self-reported data with chart review. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(Suppl):S49. [Google Scholar]

- 57.British Columbia Ministry of Health [creator] Data Extract. MOH; 2012. (2012): Medical Services Plan (MSP) Payment Information File. Population Data BC [publisher] http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data. [Google Scholar]

- 58.CIHI [creator] Data Extract. MOH; 2012. (2011): Discharge Abstract Database (Hospital Separations). Population Data BC [publisher] http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data. [Google Scholar]

- 59.BC Vital Statistics Agency [creator] Data Extract. BC Vital Statistics Agency; 2012. (2011): Vital Statistics Deaths. Population Data BC [publisher] http://www.popdata.bc.ca/data. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Solomon DH, Massarotti E, Garg R, Liu J, Canning C, Schneeweiss S. Association between disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and diabetes risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. JAMA. 2011;305(24):2525–2531. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Etminan M, Forooghian F, Brophy JM, Bird ST, Maberley D. Oral fluoroquinolones and the risk of retinal detachment. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1414–1419. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lacaille D, Guh D, Abrahamowicz M, Anis AH, Esdaile JM. Use of non-biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and risk of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(8):1074–81. doi: 10.1002/art.23913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Vera MA, Choi H, Abrahamowicz M, Kopec J, Goycochea-Robles MV, Lacaille D. Statin discontinuation and risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1020–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.142455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Vera MA, Choi H, Abrahamowicz M, Kopec J, Lacaille D. Impact of statin discontinuation on mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:809–16. doi: 10.1002/acr.21643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Avina-Zubieta JA, Abrahamowicz M, Choi HK, Rahman MM, Sylvestre MP, Esdaile JM, et al. Risk of cerebrovascular disease associated with the use of glucocorticoids in patients with incident rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:990–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.140210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Avina-Zubieta JA, Abrahamowicz M, De Vera MA, Choi HK, Sayre EC, Rahman MM, et al. Immediate and past cumulative effects of oral glucocorticoids on the risk of acute myocardial infarction in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Rheumatol (Oxford) 2013;52:68–75. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yurkovich M, Avina-Zubieta JA, Thomas J, Gorenchtein M, Lacaille D. A Systematic Review Identified Valid Comorbidity Indices Derived from Administrative Data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015 Jan;68(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: Differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(10):1075–1090. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Further evidence concerning the use of a clinical comorbidity index with ICD-9-CM administrative data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(10):1085–1090. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Uhlig T, Kvien TK. Is rheumatoid arthritis disappearing? Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(1):7–10. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.023044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Widdifield J, Paterson JM, Bernatsky S, Tu K, Tomlinson G, Kuriya B, et al. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Ontario, Canada. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;66(4):786–793. doi: 10.1002/art.38306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu A, Abrahamowicz M, Siemiatycki J. Conditions for confounding of interactions. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2016;25(3):287–96. doi: 10.1002/pds.3924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leffondré K, Abrahamowicz M, Siemiatycki J, Rachet B. Modeling smoking history: a comparison of different approaches. American journal of epidemiology. 2002;156(9):813–23. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: Results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955–2007. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(6):1576–1582. doi: 10.1002/art.27425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Davis JM, III, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Decreased cardiovascular mortality in patients with incident rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in recent years: Dawn of a new era in cardiovascular disease in RA? [abstract] [Accessed February 2, 2016];Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 67(suppl 10) doi: 10.3899/jrheum.161154. http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/decreased-cardiovascular-mortality-in-patients-with-incident-rheumatoid-arthritis-ra-in-recent-years-dawn-of-a-new-era-in-cardiovascular-disease-in-ra/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lu N, Choi HK, Schoenfeld SR, et al. Improved survival in rheumatoid arthritis: A general population-based study [abstract] [Accessed February 2, 2016];Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 67(suppl 10) http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/improved-survival-in-rheumatoid-arthritis-a-general-population-based-study/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.