Abstract

Background

Tobacco control policies affecting the point of sale (POS) are an emerging intervention, yet POS-related news media content has not been studied.

Purpose

We describe news coverage of POS tobacco control efforts and assess relationships between article characteristics, including policy domains, frames, sources, localization and evidence present, and slant towards tobacco control efforts.

Methods

High circulation state (n=268) and national (n=5) newspapers comprised the sampling frame. We retrieved 917 relevant POS-focused articles in newspapers from 01/01/2007 to 12/31/2014. Five raters screened and coded articles, 10% of articles were double-coded, and mean inter-rater reliability (IRR) was 0.74.

Results

POS coverage emphasized tobacco retailer licensing (49.1% of articles) and the most common frame present was regulation (71.3%). Government officials (52.3%), followed by tobacco retailers (39.6%), were the most frequent sources. Half of articles (51.3%) had a mixed, neutral, or anti-tobacco control slant. Articles presenting a health frame, a greater number of pro-tobacco control sources, and statistical evidence were significantly more likely to also have a pro-tobacco control slant. Articles presenting a political/rights or regulation frame, a greater number of anti-tobacco control sources, or government, tobacco industry, tobacco retailers, or tobacco users as sources were significantly less likely to also have a pro-tobacco control slant.

Conclusions

Stories that feature pro-control sources, research evidence, and a health frame also tend to support tobacco control objectives. Future research should investigate how to use data, stories, and localization to encourage a pro-tobacco control slant, and should test relationships between content characteristics and policy progression.

Keywords: point of sale, content analysis, media, advocacy, public policy

INTRODUCTION

New policies that affect the sales and marketing of tobacco products in the retail environment, or the point of sale (POS), are emerging in tobacco control, moving beyond raising tobacco product excise taxes and strong clean indoor air laws.1 Given the relationships between exposure to retail tobacco marketing, youth tobacco use initiation, and difficulty quitting, the Institute of Medicine has recommended reducing the number and density of tobacco retailers to curb tobacco consumption.1 Further, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Best Practices recommend policy and environmental interventions to promote tobacco use cessation and prevent tobacco use initiation.2 The implementation of POS tobacco control policies, such as requiring tobacco retailer licensing, restricting tobacco sales in pharmacies, or prohibiting the redemption of coupons can help achieve public health goals.3,4

State- or local-level POS policy implementation is a complex process that requires engaged support from health advocates, the general public, and policy makers. The agenda setting function of mass media suggests that the amount and nature of media content – often generated by media advocacy activities – can contribute to public and policymaker attitudes and opinions,5,6 which then influence policy change. The mass media play a powerful role in establishing what issues are salient for policymakers;7 newspapers, especially, appear to have a primary agenda-setting role in tobacco policy change.8–10

Media content can vary in ways that shape public discourse in favor of or against policy implementation. A news frame is a central organizing idea in an article that involves emphasizing certain aspects of an issue over others – carefully packaging an issue to offer context for the reader.11 The framing of news content has implications for how the issue is interpreted,12,13 the extent to which an issue is supported by the public and decision makers,12 and implied solutions.14 Often, public health advocates and the tobacco industry vie for shaping a discussion in hopes that audiences identify with the issue, and share their particular view of the argument. Relationships between frame and slant (the extent to which news content supports tobacco control objectives) were identified in news content about clean indoor air laws, such that health-framed articles were more likely to be slanted in favor of tobacco control,15–17 and rights, political or regulation-framed articles were more likely to be slanted against tobacco control.15–17

The presence of sources also shapes the news discourse.5,18,19 A source is a person or organization who gives information to news reporters and is explicitly identified by quote or paraphrase.20 An important tool for promoting policy change is including public health advocates as news sources who contribute to a pro-tobacco control slant.21–23

The use of narrative or statistical evidence can support the diffusion of health policies24 by helping to persuasively characterize the problem and solutions,16 and by educating the public about the rationale for the policy.25 For example, the presentation of relevant research evidence can properly identify a problem, aid in evidence-based solution development, and improve policymaker knowledge and support.26–28 The extent to which articles are developed with local quotes and local story angles (localization) also shapes public and policymaker support by making the issue more salient to the reader.26,27

Frames, the presence of sources, the use of narrative and data-driven evidence, and the degree of localization may impact the slant of the article29,30 or subsequent public and decision-maker support for policies.31–34 For example, two communities in Missouri with different exposure to media slant were compared with regard to their ability to pass tobacco control legislation. The community that was exposed to more anti-tobacco control articles, more articles with a ‘rights’ frame, and more articles presenting little to no evidence was less likely to pass tobacco control policy legislation as compared to its counterpoint community with lower exposures on the same variables16. One area for further research is to clarify the relationship between article slant and other article characteristics (e.g., frame, presence and type of sources, evidence structure, and degree of localization), as an important step in understanding the role of media coverage in influencing policymaking20.

The goal of this study is to describe eight years of mass media coverage of POS tobacco control efforts in a sample of high circulation US national and state-level newspapers. This POS-focused study fills a distinct gap in the literature; past work has focused largely on general tobacco issues in the US35,36, smoke free laws15,16,37,38 and tobacco taxes.17,39 In addition, we test hypotheses about the relationships between article content characteristics and overall article slant for tobacco control. We hypothesized that articles with a health frame, greater amounts of pro-tobacco control sources, both data and narrative evidence, or a local angle or quote are more likely to have an overall pro-tobacco control slant than an anti-tobacco control slant.

METHODS

Newspaper Sampling Frame

We used a content analysis method to test our hypotheses by first selecting the five highest circulating national US newspapers40. Second, for each state, the top two highest-circulating state-level newspapers were included, and additional available newspapers were added by descending circulation rate until a summed state-level circulation rate was equal to or greater than 5% of the 2010 Census state population. This sampling method is beneficial because it ensures sufficient population reach to have meaningful associations with public opinion.41

Article Search Terms

We used search terms to identify POS-related newspaper articles published in sampled newspapers between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2014. The January 1, 2007 time point was 2.5 years prior to the passage of the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA). As has been done previously by Lee, et al.,42 in a POS-related systematic review, search terms were structured to capture articles with a tobacco-related word in the headline and a POS or retail-related word in the body of the article.

Data Collection and Coding Procedures

Articles were downloaded from America’s News and ProQuest databases. Coding procedures followed a structured codebook developed iteratively through four rounds of double coding on all measures. In Round 1, two study authors (LAL, SMR) coded six pilot articles and in Round 2, two data collectors coded the same six pilot articles; after each round, inter-rater reliability (IRR) was calculated, and the codebook was revised for variables with low IRR (k<0.60). In Rounds 3 and 4, cumulative IRR was calculated for all double-coded articles in the database, including the pilot articles. The structured codebook with variables and response categories was informed by past content analyses in tobacco15–17,23,43,44 and health promotion,26 and a preliminary review of POS-related content. Inter-rater reliability (IRR) was measured with Cohen’s Kappa.45 Five coders were involved in the study: four data collectors and the lead author coded, all of whom remained in daily email communication throughout the data collection period. The lead author independently double-screened and double-coded 10% of articles and resolved coding disagreements. IRR was calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23 (Armonk, NY).

Article Inclusion Criteria

Articles retrieved via search terms were screened for study inclusion according to four variables. First, included articles had the words smoke, smoking or tobacco; cigar, little cigar, or cigarillo; cigarette, electronic cigarette, e-cigarette, or vaping device; snus, snuff, dip, chewing tobacco; or other tobacco product in the headline. Second, included articles had at least one paragraph (≥ four sentences) of tobacco-related content. Third, included articles contained a main POS theme (see Table 1), defined as one of 29 individual policy solutions within 6 overarching domains, or the FSPTCA, which contained POS provisions and acted as a focusing event opening new legal pathways towards state- and local-level POS policy change.46

Table 1.

Point-of-sale themes: overarching policy domains and individual policy solutions.

| Domain | POS Policy Solutions | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Tobacco retailer licensing, locations and density | A. B. C. D. E. F. G. H. |

Establishing or strengthening tobacco retailer licensing regulations Limiting or capping the total number of licenses in a specific area Establishing or increasing licensing fees Prohibiting tobacco sales in locations youth frequent (e.g., near schools or parks) Restricting retailers operating within a certain distance of other tobacco sellers Restricting retailers in certain zones (e.g., banning retailers in residential zones) Prohibiting the sale of tobacco products at certain establishment types (e.g., pharmacies, restaurants, prisons, military bases/ships) [Note this includes CVS voluntary policy decision to stop selling tobacco in pharmacies] Limiting number of hours or days in which tobacco can be sold |

| 2. Advertising | I. J. K. L. M. N. |

Limiting the times during which advertising is permitted (e.g., after school hours on weekdays) Limiting the placement of advertisements at certain store locations (e.g., within 1,000 feet of schools) Limiting the placement of advertisements within the store (e.g., near cash register) Limiting placement of outdoor store advertisements Limiting manner of retail advertising by banning certain types of tobacco advertisements (e.g., outdoor sandwich board style ads) Banning all types of ads regardless of content (e.g., sign codes that restrict ads to 15% of window space) |

| 3. Product Placement | O. P. Q. R. |

Banning product displays/requiring retailers to store tobacco products out of view (e.g., under counter or behind opaque shelving) Banning self-service displays for other (non-cigarette) tobacco products or all tobacco products Restricting the number of products that can be displayed (e.g., only allow retailers to display one sample of each tobacco product for sale) or the amount to square footage dedicated to tobacco products Limiting times during which products are visible (e.g., after school hours on weekdays) |

| 4. POS Health Warnings | S. T. |

Requiring graphic warnings at the point of sale Requiring the posting of Quit line information in tobacco retail stores |

| 5. Non-tax approaches to raising price | U. V. W. X. Y. |

Establishing cigarette minimum price laws Banning price discounting/multi-pack options Banning distribution or redemption of coupons Establishing mitigation feels (e.g., a fee to clean up cigarette litter) Requiring disclosure or Sunshine Law for manufacturer incentives given to retailers |

| 6. Other POS policies | Z. AA. BB. CC. |

Banning flavored other tobacco products Requiring minimum pack size for other tobacco products Raising the minimum legal sale age (MLSA) to buy tobacco products Other policy not listed here |

| 7. FSPTCA | DD. | Federal regulation as part of Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act |

The POS theme screening measure (not shown) was created by merging a commonly used47 tobacco theme coding scheme43 with a list of POS policy options;48 articles without a main POS-related theme were excluded. Fourth, news articles, letters to the editor (LTE) and opinion/editorials written by the newspaper were included; duplicate articles, photos without text, and cartoons were excluded.

Article Content Measures

Each article was coded for the presence or absence of 30 unique POS-policy options (see Table 1) and these variables: (1) frames, (2) sources, (3) evidence structure, (4) degree of localization, and (5) slant (see Table 2). Frames could be positive, negative or neutral for tobacco control objectives, and more than one frame could be present in each article; however, at least two sentences of content were required for the frame to be considered ‘present’. Frame values were adapted from previous research15–17,49 and a preliminary inductive review of sampled POS content. Sources included any individual or organization that was directly quoted in an article, without regard to whether they explicitly mentioned tobacco. Evidence structure was adapted from two previous studies16,26; evidence was defined as data (statistics/numbers) or personal anecdotes (authentic stories or narratives) within the article. In state-level newspapers, localization included the presence or absence of local quotes or local angles. In national newspapers, articles were deemed to have a local angle if the article focused on a particular region, state or city; quotes were deemed “local” if they were attributed to a person or organization from the locality that was the focus of the article. Finally, articles were coded for overall slant according to previously used measures15,16,23,35,43. We required clear statements of support for or against tobacco control to be present to justify any slant code; articles with statements both for- and against-tobacco control objectives were coded as “mixed” and articles with no opinion were coded as “neutral”.

Table 2.

Article content characteristics measures and response options.

Frames Present15–17,49

|

Source Type and Number Present16

|

Evidence Structure Present16,26

|

Degree of Localization

|

Slant15,16,23,35,43

|

Data Analysis

Since articles cluster within newspapers, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE)50,51. Outcome variables in hypothesis testing were modeled as binary categorical variables (e.g., pro-tobacco control slant versus all other). GEE model specifications included an exchangeable correlation matrix, which assumes a constant newspaper effect where within-subject observations are equally correlated and there is no ordering; a logit link function to linearize the data, standard for binary dependent variables; and, a binomial distribution of the dependent variable52. Regression coefficients produced by GEE models were exponentiated to calculate odds ratios. Mean estimates were also produced for ease of interpretation. IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23 (Armonk, NY) was used to analyze the data.

RESULTS

Newspaper Sampling Frame

A total of 5 national-level (The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and NY Daily News) and 268 state-level newspapers comprised the sampling frame. We achieved 5% population coverage for 48 of 50 states. The mean number of newspapers sampled for each state was 5.36 (Range = 1 in Delaware to 24 in California) and mean circulation level was 5.86% (Range = 1.4% in Delaware to 12.6% in Hawaii). Due to database subscription concerns, we secured only 2.0% (n=7 newspapers) and 1.4% (n=1 newspaper) coverage in Arizona and Delaware, respectively.

Sampled Articles

Search terms identified 4,600 articles for inclusion screening. Inclusion criteria led to removal of 3,683 articles: 27 articles did not meet headline criteria, 908 articles did not contain at least one paragraph of tobacco content, 2,714 did not have a main POS theme, and 34 were duplicates, photos without text, or cartoons. A total of 917 articles were included in the study: 711 news articles were included in descriptive analyses and hypothesis testing; 109 letters to the editor (LTE) and 97 opinion/editorials were included in descriptive analyses only based on a priori study aims. Mean IRR for coded variables was κ = 0.74 indicating significant agreement.

Description of POS Content

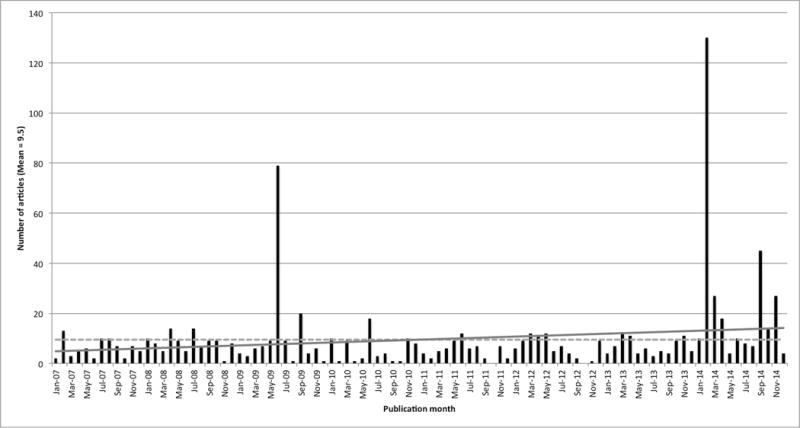

The total volume of articles published across the 8 years was 917, with an average of 114 articles per year (range 62 – 304) and 9 articles per month (range 0 – 130) (Figure 1). The highest peaks in monthly coverage corresponded with the June 2009 passage of the FSPTCA (79 articles), the February 2014 decision by CVS Health to end tobacco sales in all pharmacy locations (130 articles), and the September 2014 removal of tobacco products from CVS pharmacies (45 articles).

Figure 1.

Table 3 presents the characteristics of articles by year. News was the most frequent article type (77.5%). The top three POS policy domains discussed were tobacco retailer licensing, locations and density (49.1% of articles); other POS policies (e.g., eliminating flavors, minimum legal sale age of 21) (29.3%); and the FSPTCA (26.8%). This distribution of POS domains covered differed across years. For example, in 2009, three-quarters of articles (75.2%) contained information about the FSPTCA, and in 2014, 80.3% of articles were categorized within the tobacco retailer licensing, locations and density domain.

Table 3.

Characteristics of POS-tobacco-control-related newspaper content, by year, 2007 – 2014.

| Total (n=917) |

2007 (n=72) |

2008 (n=99) |

2009 (n=149) |

2010 (n=68) |

2011 (n=62) |

2012 (n=78) |

2013 (n=81) |

2014 (n=304) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article type, % | |||||||||

| News article | 77.5 | 75.0 | 68.7 | 75.8 | 82.4 | 82.3 | 83.3 | 80.2 | 77.3 |

| Letter to the editor | 11.9 | 15.3 | 21.2 | 6.0 | 11.8 | 11.3 | 12.8 | 12.3 | 10.9 |

| Editorial | 10.6 | 9.7 | 10.1 | 18.1 | 5.9 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 7.4 | 11.8 |

| POS Policy Domains Discussed, %* | |||||||||

| Tob. retailer licensing, locations and density | 49.1 | 36.1 | 49.5 | 15.4 | 35.3 | 33.9 | 46.2 | 30.9 | 80.3 |

| Other POS policies (e.g., flavor, MLSA) | 29.3 | 16.7 | 26.3 | 42.3 | 22.1 | 30.6 | 35.1 | 55.6 | 19.7 |

| Federal (e.g., FSPTCA) | 26.8 | 50.0 | 25.3 | 75.2 | 27.9 | 25.8 | 10.4 | 11.1 | 6.3 |

| POS health warnings | 9.7 | 6.9 | 4.0 | 23.5 | 23.5 | 17.7 | 10.4 | 7.4 | 0.7 |

| Advertising | 9.6 | 16.7 | 8.1 | 26.8 | 11.8 | 11.3 | 5.2 | 7.4 | 0.7 |

| Product placement | 7.3 | 8.3 | 4.0 | 6.1 | 8.8 | 11.3 | 7.8 | 27.2 | 2.3 |

| Non-Tax Approaches to raising price | 5.6 | 4.2 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 12.9 | 7.8 | 21.0 | 3.6 |

| Frames Present, %* | |||||||||

| Regulation | 71.3 | 90.3 | 75.8 | 97.3 | 85.3 | 74.2 | 82.1 | 86.4 | 41.8 |

| Health | 45.3 | 31.0 | 32.7 | 31.5 | 29.4 | 45.2 | 24.4 | 45.7 | 68.4 |

| Economic | 26.1 | 20.8 | 19.2 | 8.7 | 16.2 | 17.7 | 28.2 | 6.2 | 46.4 |

| Political/Rights | 17.4 | 15.3 | 26.3 | 21.5 | 20.6 | 16.1 | 29.5 | 18.5 | 9.2 |

| Other Frame | 5.4 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 2.7 | 9.0 | 3.2 | 11.5 | 8.8 | 4.3 |

| Sources Present, %*# | |||||||||

| Government or law enforcement | 52.3 | 61.3 | 47.9 | 71.6 | 60.0 | 48.0 | 63.1 | 59.7 | 37.3 |

| Tobacco retailer or retailer association | 39.6 | 21.0 | 45.2 | 9.2 | 32.7 | 32.0 | 34.4 | 32.3 | 61.6 |

| Public health advocacy group/coalition | 35.8 | 47.5 | 31.5 | 44.0 | 37.0 | 32.0 | 40.0 | 37.1 | 29.6 |

| Community member/public citizen | 23.6 | 18.0 | 24.7 | 14.7 | 13.0 | 22.0 | 18.5 | 19.4 | 33.3 |

| Tobacco industry or spokesperson | 22.0 | 32.3 | 13.7 | 39.4 | 31.5 | 24.0 | 20.0 | 14.5 | 14.1 |

| Health department official/staff | 21.5 | 18.0 | 27.4 | 8.3 | 20.4 | 28.0 | 16.9 | 35.5 | 22.9 |

| Educational/research institution faculty | 12.7 | 13.1 | 6.9 | 15.6 | 7.4 | 22.0 | 3.1 | 14.5 | 14.1 |

| Smoker, vaper, tobacco user - individual | 10.1 | 6.5 | 9.6 | 10.1 | 1.9 | 8.0 | 3.1 | 19.4 | 12.9 |

| Hospital/health care provider | 7.0 | 4.9 | 1.4 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 3.2 | 14.1 |

| Smoker, vaper, tobacco user – org/association | 2.5 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 14.5 | 2.0 |

| Evidence, % | |||||||||

| No evidence | 31.4 | 31.9 | 35.4 | 34.9 | 55.9 | 37.1 | 29.5 | 28.4 | 22.8 |

| Data/statistics only, with a source | 35.1 | 27.8 | 27.3 | 24.2 | 17.6 | 37.1 | 42.3 | 35.8 | 46.1 |

| Data/statistics only, without a source | 20.9 | 26.4 | 23.2 | 29.5 | 17.6 | 22.6 | 17.9 | 21.0 | 16.1 |

| Both data and narrative/story | 9.2 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 9.4 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 6.4 | 11.1 | 10.9 |

| Story/narrative/personal anecdotes only | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.6 |

| Localization, % | |||||||||

| Localized: Both local quote and local angle | 41.8 | 38.6 | 54.5 | 20.8 | 41.2 | 51.6 | 65.4 | 50.6 | 35.9 |

| Not localized: No local quote, nor local angle | 40.5 | 34.7 | 25.3 | 66.4 | 42.6 | 27.4 | 17.9 | 32.1 | 44.1 |

| Partially localized: Local quote or local angle only | 17.6 | 16.7 | 20.2 | 12.8 | 16.1 | 20.9 | 16.7 | 17.2 | 19.7 |

| Overall Slant, % | |||||||||

| Pro-tobacco control | 49.7 | 50.7 | 42.4 | 48.3 | 37.3 | 45.2 | 35.9 | 55.6 | 58.7 |

| Mixed (both points of view) | 32.7 | 31.0 | 38.4 | 31.5 | 37.3 | 32.3 | 44.9 | 32.1 | 27.7 |

| Neutral (no opinion) | 11.2 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 8.7 | 19.4 | 14.5 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 10.9 |

| Anti-tobacco control | 6.5 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 11.4 | 6.0 | 8.1 | 9.0 | 1.2 | 2.6 |

Percents do not sum to 100% because more than one source type could have been quoted, more than one frame could be present, or more than one policy domain discussed in the same article.

Hospitality industry source not shown because total % = 0.6. POS = Point of sale. MLSA = Minimum Legal Sales Age. FSPTCA = Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act.

Across the entire study period, the two most common frames present were regulation (e.g., Headline: “Round Four Revised tobacco-license law merits adoption”, “City eyes new tobacco shop rules”) (71.3%), and health (e.g., Headline: “Health group wants to snuff out tobacco in pharmacies”, “Preventing death tobacco regulation will be welcome reality”) (45.3%). Multiple frames were often present in the same article. For example, 14.2% (n=130) of all articles contained both health and economic frames, and 22.9% (n=210) of all articles contained both a health and regulation frame. Nearly 80% of articles included a source (data not shown). Government or law enforcement was the most frequently cited source, present in 52.3% of articles, followed by tobacco retailers (39.6%) and public health advocacy groups (35.8%). The presence of the tobacco industry as sources in articles waned over time during the study period, whereas the presence of tobacco retailers as sources in articles increased over time. With regard to the use and structure of evidence in POS articles, nearly one-third of articles (31.4%) contained no evidence at all; this pattern remained fairly consistent across the eight years (data not shown). Another one-third of articles (35.1%) contained only data with a source, and less than 10% contained both data and narrative (9.2%). The degree of localization in POS articles was mixed: 40.5% contained neither a local quote, nor a local angle; 41.8% contained both a local quote and a local angle. About half of POS-related content was slanted in favor of tobacco control and prevention activities (49.7%), nearly one-third (32.7%) reported mixed points of view, and only 6.5% of articles had an anti-tobacco control slant. Slant varied by article type, such that 40.7% (n=288 of 708) of news articles had a pro-tobacco control slant, compared to 84.5% (n=82 of 97) of editorials and 77.1% (n=84 of 109) of LTEs.

Relationships between Content Characteristics

Our results testing relationships between content characteristics and slant indicate partial support for our hypotheses (Table 4). News articles with a health frame present were more likely to have a pro-tobacco control slant than any other slant (anti-tobacco control, mixed or neutral). News articles with a political/rights or regulation frame present were less likely to have a pro-tobacco control slant than any other slant.

Table 4.

Adjusted odds ratios produced via GEE for the association of article content characteristic with pro-tobacco control slant among news articles, 2007 to 2014

| News article characteristics (n=711) | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | Mean Estimate | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frames Present | ||||

| Regulation | 0.58 | 0.42 – 0.80 | 0.41 | 0.0009* |

| Health | 2.39 | 1.80 – 3.19 | 0.57 | <0.0001* |

| Economic | 0.91 | 0.66 – 1.25 | 0.43 | 0.551 |

| Political/Rights | 0.18 | 0.11 – 0.30 | 0.15 | <0.0001* |

| Other Frame | 2.09 | 0.81 – 5.42 | 0.62 | 0.129 |

| Sources Present | ||||

| Government or law enforcement | 0.54 | 0.40 – 0.72 | 0.40 | <0.0001* |

| Tobacco retailer or retailer association | 0.68 | 0.46 – 0.99 | 0.42 | 0.045* |

| Public health advocacy group/coalition | 1.00 | 0.72 – 1.40 | 0.47 | 0.992 |

| Community member/public citizen | 0.56 | 0.39 – 0.79 | 0.36 | 0.001* |

| Tobacco industry or spokesperson | 0.38 | 0.26 – 0.55 | 0.29 | <0.0001* |

| Health department official/staff | 1.28 | 0.94 – 1.76 | 0.52 | 0.122 |

| Educational/research institution faculty | 0.80 | 0.54 – 1.20 | 0.42 | 0.290 |

| Smoker, vaper, tobacco user – individual | 0.43 | 0.25 – 0.73 | 0.29 | 0.002* |

| Hospital/health care provider | 1.11 | 0.58 – 2.13 | 0.49 | 0.758 |

| Smoker, vaper, tobacco user – org/association | 0.48 | 0.22 – 1.02 | 0.30 | 0.058 |

| Greater number of pro-tobacco-control sources1 | 2.58 | 1.22 – 5.47 | 0.47 | 0.013 |

| Greater number of anti-tobacco-control sources2 | 0.39 | 0.18 – 0.82 | 0.25 | 0.013 |

| Evidence Types Present | ||||

| Data/statistics only, with a source | 1.04 | 0.71 – 1.52 | 0.49 | 0.852 |

| Data/statistics only (w/or w/out source) | 1.57 | 1.13 – 2.18 | 0.50 | 0.007* |

| Both data and narrative/story | 0.95 | 0.57 – 1.58 | 0.44 | 0.838 |

| Story/narrative/personal anecdotes only | 1.20 | 0.59 – 2.47 | 0.49 | 0.617 |

| Any story/narrative (w/or w/o data) | 1.01 | 0.65 – 1.58 | 0.45 | 0.966 |

| Degree of Localization Present | ||||

| Localized: Both local quote and local angle (vs. all other) | 1.24 | 0.90 – 1.72 | 0.47 | 0.194 |

| Not localized: No local quote, nor local angle (vs. all other) | 0.90 | 0.63 – 1.27 | 0.43 | 0.536 |

| Partially localized: Local quote (w/or w/o local angle) | 0.84 | 0.62 – 1.16 | 0.42 | 0.290 |

| Partially localized: Local angle (w/or w/o local quote) | 0.86 | 0.61 – 1.20 | 0.43 | 0.367 |

Pro-tobacco control sources include public health advocacy organization or coalition, health department official or staff, and hospital or health care provider.

Anti-tobacco-control sources include tobacco industry or spokesperson, tobacco retailer or retailer association, smoker/vaper/tobacco user – individual, or smoker/vaper/tobacco user – organization/association. POS = Point of sale. MLSA = Minimum Legal Sales Age. FSPTCA = Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act.

Second, articles with a greater number of pro-tobacco control sources (than anti-tobacco control sources) were more likely to have a pro-tobacco control slant. Surprisingly, the presence of a public health advocacy group or source was not associated with a pro-tobacco control slant. The presence of government or law enforcement, a concerned citizen, the tobacco industry, tobacco retailers, or an individual tobacco user was negatively associated with a pro-tobacco control slant.

Third, articles with data or statistics present (with or without a source) were more likely to have a pro-tobacco control slant than any other slant. No difference between pro- or other-slant was found for news articles with both data and narrative evidence present. Further, in separate analyses, we found that evidence (either data or story) was more likely to be present in certain POS themes (e.g., POS health warnings (χ = 8.398, df = 1, p = .004), advertising (χ = 4.017, df = 1, p = .045), and non-tax approaches to raising price (χ = 4.679, df = 1, p = .031)), compared to others.

Finally, degree of localization was not associated with slant, even when national newspapers were excluded from the analysis (data not shown). In this sample, news articles with or without a local quote or angle were no more or less likely to have a pro-tobacco control slant.

DISCUSSION

In our newspaper sample, average overall volume of POS-related content, from 2007–2014, was just 9 unique articles per month. However, major peaks in coverage captured national POS events such as the June 2009 passage of the FSPTCA or CVS ending tobacco sales, and minor peaks covered the emergence of local POS policy innovations, such as the September 2009 graphic health-warning requirement in New York City (NYC). This average volume may be related to the newness of POS work for many state and local tobacco control practitioners.53

We also examined the characteristics of POS-related content. Covered POS policy domains waxed and waned according to national and local POS activities. At the national level, two major events occurred: the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA), which contained many POS provisions (e.g., prohibition of candy or fruit flavored cigarettes; minimum package size for cigarettes; proposed graphic health warnings; permitting local- and state-level restrictions on the time, place and manner of tobacco advertising), and the CVS voluntary decision to end tobacco sales, which was coded in this study as the removal of tobacco sales in pharmacies within the tobacco retailer licensing, locations and density domain. The POS advertising and POS health warnings domains were common in 2009 due to FSPTCA provisions, but dropped off significantly through the remainder of the study period as activity in this domain declined due to legal restrictions and feasibility. The non-tax price approaches domain was frequent in 2013 based on the NYC Sensible Tobacco Enforcement Policies (STEP), which included provisions that prohibited retailers from redeeming coupons and offering price discounts, and established a minimum price for cigarettes and little cigars. Ultimately, national policy was the main driver of total content volume and local policy drove the differentiation in POS domain coverage over time.

The regulation frame was most frequently present throughout the study period, except in 2014 during the CVS transition when the health frame was most present. Frame has been measured in many tobacco-related news content analyses, particularly in coverage of smoke-free laws and tax initiatives,14,17,38,49,54–56 and the heavy presence of the regulation frame in POS-related content may be unique from past work. In this study, the regulation frame was present in 71.3% of articles; it was a main theme 22.1% of articles retrieved from a national surveillance system between 2004 and 2010.36 This is likely due to variation in how researchers define and measure frames (e.g., as themes or arguments). However, it is also possible that since 2007, the news media has become more focused on the role and impact of government regulations on health and business.

Tobacco retailers and the tobacco industry were much more present as sources in POS content than public health advocacy groups, health departments, or health care providers. Public health sources were present in only about one-third of articles (35%), suggesting an opportunity to enhance the visibility of public health advocates in the media. Whereas the tobacco industry and organizations such as the National Association of Tobacco Outlets (NATO) or National Association of Convenience Stores (NACS) maintain a sophisticated public relations engine to remain profitable, public health practitioners may 1) not have the resources to devote to public relations; 2) not share that priority; 3) lack capacity as spokespeople or media advocates; or 4) feel constrained by anti-lobbying guidelines required by funders or government agencies. It was surprising to find so few POS articles that contained both statistical evidence and narrative stories, particularly with a local angle, since these are considered powerful tools to facilitate public and policy maker support for policy implementation26,27,57. The need for greater use of data, stories, and localization in POS offers an opportunity for stronger relationships between newspaper staff, journalists and public health practitioners.

Although presence of a health frame was positively associated with a pro-tobacco control slant, political/rights and regulation frames were negatively associated with a pro-tobacco control slant in our data. However, fewer than half of articles (45.3%) contained a health frame, and nearly three-quarters of POS articles (71.3%) contained a regulation frame. Not surprisingly, source is also related to slant, such that the common presence of government officials (52.3% of articles), tobacco retailers (39.6%), or the tobacco industry (22.0%) as sources make a purely pro-tobacco control slant less likely, as compared to a mixed, neutral or anti-tobacco control slant. POS content appears to credit tobacco retailers as important members of the local business community, rather than as contributors to the continued tobacco epidemic through targeted marketing. When statistical evidence is present, the chance of pro-tobacco control slant is greater, however data with or without a source appeared only about one-third of the time. It may be that POS policies are perceived by stakeholders to threaten business rather than promote health. This is important information for practitioners working to advance POS policies, as they have significant potential to shape future media coverage by working to uncouple the assumed association between more POS policies and a negative effect on business.

This study is limited in that results are only generalizable to the current sample of 273 newspapers; however, the newspaper sample is large enough, with sufficient population reach, that it provides a helpful first look at POS content. Further, human coding of qualitative content is subject to error, but data collectors were well trained and IRR measures were well within acceptable ranges.45 Sufficient data may not have been available to properly test relationships between localization, evidence structure and slant: this is an area for future work. Given that content related to POS policy implementation brings together politics, business, and health, future research should track changes in the volume and characteristics of POS content over time, and should identify communication strategies that support POS policy progression.

Describing the national media agenda as it relates to POS tobacco control efforts is an important step in policy change processes. This is one of few tobacco-related content analysis studies to test a priori hypotheses describing the relationships between content characteristics22,47,58,59 and slant. This study is important because, in practice, public health workers partner with the media to serve as news sources, work with concerned citizen coalitions to define issues and solutions, and employ persuasive communication strategies to package issues in meaningful ways.7 However, practitioners working on POS efforts report a lack of communication tools as a barrier to further progress.53 Findings from this study may assist with communication tool development or offer important lessons for public health advocates as they partner with the media and work independently to generate media coverage that supports tobacco control policies.

KEY MESSAGES (SUMMARY BOX).

What this paper adds

This paper describes, for the first time, newspaper coverage of point-of-sale (POS) tobacco control efforts in the United States from a robust sample of national- and state-level newspapers beginning 01/01/2007 to 12/31/2014. In this study, we also assess relationships between article characteristics (e.g., frames, sources, localization and evidence present, and slant towards tobacco control efforts).

What is already known on this subject

For decades, researchers have been describing news media content related to tobacco, generally, and to tobacco control policies such as smoke free laws or tobacco taxes

No studies, to our knowledge, have described news content related specifically to tobacco control and prevention efforts affecting the retail environment, or POS

Few content analysis studies test a priori hypotheses about the relationships between variables, or measure a broad set of constructs related to policy progression

What important gaps in knowledge exist on this topic

Tobacco-related media content remains understudied in that most content analyses are descriptive, without a priori hypotheses, or bivariate statistics to test predicted relationships between content characteristics

Despite the theoretical underpinning that media content predicts both public opinion and the policy agenda, no studies have reviewed a broad set of content characteristics thought to be involved in policy progression

No research to date has focused specifically on news media content (newspaper or other channel) related to emerging retail-focused policy interventions.

What this study adds

We now know that POS coverage from 2007 to 2014 emphasized tobacco retailer licensing policies, that the most common news frame was regulation, and that government officials and tobacco retailers are the most common sources present.

Articles presenting a health frame, a greater number of pro-tobacco control sources, and statistical evidence were significantly more likely to also have a pro-tobacco control slant than to have an anti-tobacco control slant; this is important information for tobacco control advocates who partner with the media.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Stephanie Bangel, Maryka Lier, Shauna Rust, and Rachel Wilbur who coded POS news content for the study.

Conflict of interest statement:

Funding for this study was provided by a grant from the National Cancer Institute to Dr. Ribisl (Multi-PI) — “Maximizing state & local policies to restrict tobacco marketing at point of sale,” 1U01CA154281. The funders had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, writing, or interpretation.

Financial disclosures:

AE Myers is Co-Founder/Executive Director and KM Ribisl serves as Chair of the Board of Directors of the 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, Counter Tools (http://countertools.org), from which they receive compensation. Counter Tools provides technical assistance on point of sale tobacco control issues and distributes store mapping and store audit tools. KM Ribisl and AE Myers have a royalty interest in a store audit and mapping system owned by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Neither the store audit tool, nor the mapping system, was used in this study.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Ending the tobacco problem: A blueprint for the nation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs - 2014. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Public Health Systems Science. Point-of-Sale Strategies: A Tobacco Control Guide St Louis Center or Public Health Systems Science. George Warren Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St Louis and the Tobacco Control Legal Consortium; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers AE, Hall MG, Isgett LF, et al. A comparison of three policy approaches for tobacco retailer reduction. Prev Med. 2015;74:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallack LM, Dorfman L. Media advocacy: a strategy for advancing polity and promoting health. Health Educ Behav. 1996;23:293–317. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCombs ME. The Evolution of Agenda-Setting Research: Twenty-five Years in the Marketplace of Ideas. Journal of Communication. 1993;43(2):58–66. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 3rd. San Francisco, California: Josey-Bass; 2002. with Foreward by Noreen M Clark. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster C, Thrasher J, Kim SH, et al. Agenda-building influences on the news media’s coverage of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s push to regulate tobacco, 1993–2009. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2012;35(3):303–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilberg SE, McCombs M, Nicholas D. The State of the Union Address and the Press Agenda. Journal Q. 1980 Winter;57(4):584. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson DE, Pederson LL, Mowery P, et al. Trends in US newspaper and television coverage of tobacco. Tob Control. 2013;24(1):94–99. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-050963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Entman RM. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J Commun. 1993;43(4):51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorfman L, Wallack L, Woodruff K. More than a message: framing public health advocacy to change corporate practices. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32(3):320–36. doi: 10.1177/1090198105275046. discussion 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nisbet MC, Maibach E, Leiserowitz A. Framing peak petroleum as a public health problem: audience research and participatory engagement in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(9):1620–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menashe CL, Siegel M. The power of a frame: an analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues–United States, 1985–1996. J Health Commun. 1998;3(4):307–25. doi: 10.1080/108107398127139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moshrefzadeh A, Rice W, Pederson A, et al. A content analysis of media coverage of the introduction of a smoke-free bylaw in Vancouver parks and beaches. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(9):4444–53. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10094444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bach LE, Shelton SC, Moreland-Russell S, et al. Smoke-free workplace ballot campaigns: case studies from missouri and lessons for policy and media advocacy. A J Health Promot. 2013;27(6):e124–33. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.120405-QUAN-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris JK, Shelton SC, Moreland-Russell S, et al. Tobacco coverage in print media: the use of timing and themes by tobacco control supporters and opposition before a failed tobacco tax initiative. Tob Control. 2010;19(1):37–43. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.032516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neiderdeppe J, Farrelly MC, Wenter D. Media advocacy, tobacco control policy change and teen smoking in Florida. Tob Control. 2007;16:47–52. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman S, Lupton D. The Fight for Public Health: Principles and Practice of Media Advocacy. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riffe D, Lacy S, Fico FG. Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research. 2nd. New York, London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallack L, Woodruff K, Dorfman L, Diaz I. News for a Change: An Advocate’s Guide for Working with the Media. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institute NC, editor. Tobacco Control Monograph No 19. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2008. The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakefield MA, Brennan E, Durkin SJ, et al. Making news: the appearance of tobacco control organizations in newspaper coverage of tobacco control issues. Am J Health Promot. 2012;26(3):166–71. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.100304-QUAN-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brownson RC, Gurney JG, Land GH. Evidence-based decision making in public health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 1999;5(5):86–97. doi: 10.1097/00124784-199909000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCombs ME, Shaw DL. The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media. Public Opin Q. 1972;36(2):176–87. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caburnay CA, Kreuter MW, Luke DA, et al. The news on health behavior: coverage of diet, activity, and tobacco in local newspapers. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(6):709–22. doi: 10.1177/1090198103255456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brownson RC, Dodson EA, Stamatakis KA, et al. Communicating evidence-based information on cancer prevention to state-level policy makers. J Natl Cancer Inst Mongr. 2011;103(4):306–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brownson RCBP, Dieffenderfer B, Haire-Joshu D, Health GW, Kreuter MW, Myers BA. Evidence-Based Interventions to Promote Physical Activity: What Contributes to Dissemination by State Health Departments. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(IS):S66–S78. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perloff RM. The Dynamics of Persuasion. 2nd. Malwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson DE, Croyle RT. Making Data Talk. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagelhout GE, van den Putte B, de Vries H, et al. The influence of newspaper coverage and a media campaign on smokers’ support for smoke-free bars and restaurants and on second hand smoke harm awareness: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Netherlands Survey. Tob Control. 2012;21:24–29. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.040477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coleman R. The effects of news stories that put crime and violence into context: testing the public health model of reporting. J Health Commun. 2002;7:401–25. doi: 10.1080/10810730290001783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Domke DMK, Torres M. News media, racial perceptions, and political cognition. Communic Res. 1999;26:570–607. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson J. Switching social identities: the influence of editorial framing on reader attitudes toward affirmative action and African Americans. Communic Res. 2005;32:503–28. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clegg Smith K, Wakefield M, Edsall E. The Good News about Smoking: How do US Newspapers Cover Tobacco Issues? J Public Health Policy. 2006;27(2):166–81. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson DE, Pederson LL, Mowery P, Bailey S, Sevilimenu V, London J, Babb S, Pechacek T. Trends in US Newspaper and Television Coverage of Tobacco. Tob Control. 2013 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-050963. Published Online First: July 17, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuiper NM, Frantz KE, Cotant M, et al. Newspaper coverage of implementation of the michigan smoke-free law: lessons learned. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(6):901–8. doi: 10.1177/1524839913476300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magzamen S, Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Print media coverage of California’s smokefree bar law. Tob Control. 2001;10(2):154–60. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thrasher JF, Kim SH, Rose I, et al. Print Media Coverage Around Failed and Successful Tobacco Tax Initiatives: The South Carolina Experience. A J Health Promot. 2014 doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130104-QUAN-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Editor & Publisher. 92nd Annual Newspaper DataBook: Dailies 2013. Irvine CA: Duncan McIntosh Company Inc; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clegg Smith K, Wakefield MA, Terry-McElrath Y, et al. Relation between newspaper coverage of tobacco issues and smoking attitudes and behaviors among American teens. Tob Control. 2008;17:17–24. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JGL, Henriksen L, Myers AE, et al. A systematic review of store audit methods for assessing tobacco marketing and products at the point of sale. Tob Control. 2013 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050807. January 15 Online First. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clegg Smith K, Wakefield M, Siebel C, et al. Coding the News: The Development of a Methodological Framework for Coding and Analyzing Newspaper Coverage of Tobacco Issues. ImpacTeen Research Paper Series. 2002;(21) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dorfman L. Studying the News on Public Health: How Content Analysis Supports Media Advocacy. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(Suppl 3):S217–S26. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding Intraobserver Agreement: The Kappa Statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):360–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreland-Russell S, Combs T, Jones J, et al. State level point-of-sale policy priority as a result of the FSPTCA. AIMS Public Health. 2015;2(4):709–18. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2015.4.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Durrant R, Wakefield M, McLeod K, et al. Tobacco in the news: an analysis of newspaper coverage of tobacco issues in Australia, 2001. Tob Control. 2003;12(Suppl 2):ii75–81. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Center for Public Health Systems Science. Point-of-Sale: A Tobacco Control Guide. St Louis: Center for Public Health Systems Science, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St Louis; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Champion D, Chapman S. Framing pub smoking bans: An analysis of Australian print news media coverage, March 1996–March 2003. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(8):679–84. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.035915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stokes ME, Koch GG. Categorical Data Analysis Using the SAS System. 2nd. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liang K, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrics. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ballinger GA. Using Generalized Estimating Equations for Longitudinal Data Analysis. Organ Res Methods. 2004;7:127–49. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Center for Public Health Systems Science. Point-of-Sale Report to the Nation: The Tobacco Retail and Policy Landscape. St Louis, MO: Center for Public Health Systems Science at the Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St Louis and the National Cancer Institute, State and Community Tobacco Control Research; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lima JC, Siegel M. The tobacco settlement: an analysis of newspaper coverage of a national policy debate, 1997–98. Tob Control. 1999;8(3):247–53. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.3.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wackowski OA, Lewis MJ, Hrywna M. Banning smoking in New Jersey casinos—A content analysis of the debate in print media. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(7):882–88. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.570620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fahy D, Trench B, Clancy L. Communicating Contentious Health Policy: Lessons from Ireland’s Workplace Smoking Ban. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13:331–38. doi: 10.1177/1524839909341554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brownson RC, Ballew P, Dieffenderfer B, et al. Evidence-based interventions to promote physical activity: what contributes to dissemination by state health departments. A J Prev Med. 2007;33(1 Suppl):S66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.011. quiz S74–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Long M, Slater MD, Lysengen L. US news media coverage of tobacco control issues. Tob Control. 2006;15(5):367–72. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith KC, Terry-McElrath Y, Wakefield M, et al. Media advocacy and newspaper coverage of tobacco issues: A comparative analysis of 1 year’s print news in the United States and Australia. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(2):289–99. doi: 10.1080/14622200500056291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]