Abstract

AIM

To determine the possibility that diabetes mellitus promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma via glyceraldehyde (GA)-derived advanced glycation-end products (GA-AGEs).

METHODS

PANC-1, a human pancreatic cancer cell line, was treated with 1-4 mmol/L GA for 24 h. The cell viability and intracellular GA-AGEs were measured by WST-8 assay and slot blotting. Moreover, immunostaining of PANC-1 cells with an anti-GA-AGE antibody was performed. Western blotting (WB) was used to analyze the molecular weight of GA-AGEs. Heat shock proteins 90α, 90β, 70, 27 and cleaved caspase-3 were analyzed by WB. In addition, PANC-1 cells were treated with GA-AGEs-bovine serum albumin (GA-AGEs-BSA), as a model of extracellular GA-AGEs, and proliferation of PANC-1 cells was measured.

RESULTS

In PANC-1 cells, GA induced the production of GA-AGEs and cell death in a dose-dependent manner. PANC-1 cell viability was approximately 40% with a 2 mmol/L GA treatment and decreased to almost 0% with a 4 mmol/L GA treatment (each significant difference was P < 0.01). Cells treated with 2 and 4 mmol/L GA produced 6.4 and 21.2 μg/mg protein of GA-AGEs, respectively (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01). The dose-dependent production of some high-molecular-weight (HMW) complexes of HSP90β, HSP70, and HSP27 was observed following administration of GA. We considered HMW complexes to be dimers and trimers with GA-AGEs-mediated aggregation. Cleaved caspase-3 could not be detected with WB. Furthermore, 10 and 20 μg/mL GA-AGEs-BSA was 27% and 34% greater than that of control cells, respectively (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01).

CONCLUSION

Although intracellular GA-AGEs induce pancreatic cancer cell death, their secretion and release may promote the proliferation of other pancreatic cancer cells.

Keywords: Tumor promotion, Glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation-end products, Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Core tip: The mechanisms promoting pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) in the pancreas of Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients have not yet been elucidated. We hypothesized that glyceraldehyde (GA)-derived advanced glycation-end products (GA-AGEs) promote PDAC. PANC-1 cells were treated with GA, which induced the production of intracellular GA-AGEs and cell death. The high-molecular-weight complexes of heat shock proteins were produced after GA treatment in a dose-dependent manner. GA-AGEs-bovine serum albumin promoted the proliferation of PANC-1 cells. Although intracellular GA-AGEs induce pancreatic cancer cell death, their secretion and release may promote the proliferation of other pancreatic cancer cells.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is a highly lethal disease with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 5%[1,2]. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) accounts for approximately 90% of malignancies in the pancreas[3]. The incidence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is increasing worldwide each year, and this condition may result in life-changing complications. A total of 415 million adults are already estimated to have DM (this will increase to 652 million adults by 2040)[4]. Type 2 DM (T2DM), the most common type of DM, has been shown to increase the risk of pancreatic cancer by more than 50%; furthermore, T2DM patients with pancreatic cancer have worse prognosis and shorter survival time than those without the disease[5,6].

However, the mechanisms promoting PDAC in the pancreas of T2DM patients have not yet been elucidated. Therefore, we focused on hyperglycemia, a characteristic of T2DM. Glucose and fructose have been shown to induce the production of advanced glycation-end products (AGEs)[7-12], which have, in turn, been implicated in the pathogeneses of a number of lifestyle-related diseases. Toxic and non-toxic AGEs exist among the various types of AGE structures generated in vivo. We previously identified AGEs derived from glyceraldehyde (GA), a glucose/fructose metabolism intermediate, also known as GA-AGEs[7-12]. We designated GA-AGEs as toxic AGEs (TAGE) because of their cytotoxicity and involvement in insulin resistance, hypertension, diabetic complications, cardiovascular diseases, dementia, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer[7-12].

We hypothesized that the production of GA-AGEs in pancreatic ductal cancer cells in the pancreas of T2DM patients promotes PDAC. In the present study, we incubated PANC-1, a human pancreatic ductal cancer cell line, with GA to generate intracellular GA-AGEs. We analyzed cell viability, intracellular GA-AGEs, cell death-associated proteins, and the high-molecular-weight (HMW) complexes that appeared and increased in a GA dose-dependent manner. Then, we investigated whether secreted GA-AGEs from GA-AGEs-producing pancreatic cancer cells promoted tumors. In this study, we also examined the effects of GA-AGEs-bovine serum albumin (GA-AGEs-BSA) on the proliferation of PANC-1 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The human pancreatic cancer cell line PANC-1 (ATCC-CRL-1469) was purchased from ATCC (VA, United States). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), penicillin-streptomycin solution, and L-glutamine solution were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, United States). 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) was obtained from Dojindo Laboratories (Kumamoto, Japan). GA was purchased from Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Kyoto, Japan). The Western re-probe kit was purchased from Funakoshi Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). The protein assay kit for the BCA method was purchased from Bio-Rad (CA, United States). The protein assay kit for the Bradford method was obtained from Takara Bio, Inc. (Otsu, Japan). All other reagents and kits were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka Japan). The non-glycated control bovine serum albumin (BSA) and GA-AGEs-BSA were prepared as described previously[13].

Cell culture, cell seeds, and GA treatment

PANC-1 cells were grown in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 100 mL/L fetal bovine serum (FBS; Bovogen-Biologicals, VIC, Australia), 2.0 mmol/L) glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin under standard cell culture conditions (humidified atmosphere, 50 mL/L CO2, 37 °C). Cells were seeded (1.9 × 104 cells/cm2) on various plates, culture dishes (Becton-Dickinson, NJ, United States), and glass chambers (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA, United States) and incubated for 24 h before GA treatment. GA was diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and filtered before being added to PANC-1 cells. The volume of PBS (including GA) was 2.0 μL/100 μL of the total medium volume. All experiments were performed 24 h after GA treatment.

Cell viability and proliferation

Cell viability and proliferation were assessed by the WST-8 assay. Three hours after medium change and treatment with the WST-8 reagent solution, absorbance was measured at 450 nm and 650 nm using a microplate reader (Labsystems Multiskan ascent, Model No. 354; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Kanagawa, Japan). A blank value was obtained (OD 450 nm-OD 650 nm) from a well containing medium only. Cell viability and proliferation (%) = OD of GA-treated cells/OD of control cells.

Slot blotting analysis for GA-AGEs

Lysis buffer for slot blotting (SB): A solution containing 2 mol/L thiourea, 7 mol/L urea, 40 g/L CHAPS, and 30 mmol/L Tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane (Tris) was diluted in ultra-pure water. Then, this solution and 30 g/L of ethylenediamine-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany) solution was mixed (9:1) to prepare the thiourea/urea lysis buffer.

Preparation of rabbit anti-GA-AGE antibody: An immunoaffinity-purified rabbit anti-GA-AGE antibody was prepared as described previously[13]. The immunoaffinity-purified anti-GA-AGE antibody did not recognize well-characterized AGE structures such as Nε-(carboxymethyl) lysine, Nε-(carboxyethyl) lysine, pyrraline, pentosidine, argpyrimidine, imidazolone, glyoxal-lysine dimers, methylglyoxal-lysine dimers, or GA-derived pyridinium. Additionally, it did not recognize other AGEs including glucose- and fructose-derived AGEs, the structures of which are currently unknown. This anti-GA-AGE antibody specifically recognized unique and unknown GA-AGE structures.

Neutralization of the anti-GA-AGE antibody for SB analysis: Tween 20 at a final concentration of 0.5 mL/L (GE Healthcare, Tokyo, Japan) was dissolved in PBS (PBS-T). Non-fat skimmed milk (SM; Nacalai Tesuque) at a final concentration of 5.0 g/L was dissolved in PBS-T (5.0 g/L SM-PBS-T). The anti-GA-AGE antibody (1:500) was incubated with a GA-AGEs-BSA solution at a final concentration of 250 mg/L in 5.0 g/L SM-PBS-T at room temperature for 1 h.

Preparation of cell lysates and SB analysis: Cells were washed with PBS and harvested with thiourea/urea lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were measured by the Bradford protein assay kit, using BSA as a standard. Cell lysates containing 2.0 μg of protein were maintained. Thiourea/urea lysis buffer was added to all samples to ensure equal final volimes.

The standard GA-AGEs-BSA solution and a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated molecular marker (HRP-MM; Bionexus, CA, United States) were dissolved in thiourea/urea lysis buffer. Then, a final volume of 200 μL was obtained by adding PBS.

The polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, MA, United States), which was set on the SB instrument (BIO-DOT SF, Bio-Rad), was washed with PBS. Each sample, standard GA-AGEs-BSA solution, and HRP-MM solution was then added to the membrane under vacuum conditions. PBS was added to wash the membrane. The membrane was then washed with ultra-pure water for 1 min, and cut to prepare two membranes: (1) the membrane for the anti-GA-AGE antibody; and (2) the membrane for the neutralized anti-GA-AGE antibody. Both membranes were blocked at room temperature for 1 h using 50 g/L SM-PBS-T. After being washed, each membrane was incubated with the anti-GA-AGE antibody (1:500) or the neutralized anti-GA-AGE antibody in 5.0 g/L SM-PBS-T at room temperature for 4 h. After being washed with 5.0 g/L SM-PBS-T, both membranes were incubated with an HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark; 1:2000) in 5.0 g/L SM-PBS-T at room temperature for 1 h. Then, membranes were washed with PBS-T. Immunoreactive complexes were visualized using the ImmunoStar LD kit. The band densities on the membranes were measured using the LAS-4000 fluorescence imager (GE Healthcare, Tokyo, Japan) and expressed in arbitrary units (AU). The densities of HRP-MM bands were used to correct for differences in densities between membranes. The amount of GA-AGEs in samples was calculated based on a standard curve for GA-AGEs-BSA.

Immunostaining

PANC-1 cells were cultured in a glass chamber for 24 h. After removing medium and washing with PBS, fresh medium was added to the dish. Cells were then treated with GA and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Triton X-100 and BSA were dissolved in PBS (TritonX-100-PBS and BSA-PBS). Cells were fixed in 16 g/L paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min, rinsed with PBS, permeabilized with 1.0 mL/L Triton X-100-PBS for 10 min and then rinsed with PBS, followed by 1.0 g/L BSA-PBS. Finally, cells were incubated with 30 g/L BSA-PBS (blocking step) for 1 h. After being washed with 1.0 g/L BSA-PBS, cultured cells were incubated with the anti-GA-AGE antibody dissolved in 10 g/L BSA-PBS (1:100) for 1 h. Cells were then washed three times with 1.0 g/L BSA-PBS and incubated with the HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:1000) for 1 h. After being washed with 1.0 g/L BSA-PBS and PBS, cells were incubated for 5 min with 0.2 g/L 3,3’-diaminoenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Dojindo) and 5.0 mL/L H2O2 in PBS. Cells were briefly counterstained with hematoxylin. Optical microscopic examination was performed using a microscope system (OLYMPUS Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan).

Western blotting analysis

Cells were harvested with a radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) solution with 3.0 g/L protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science) solution. Protein concentrations were assessed by the BCA assay kit, using BSA as a standard. Lysates (15 μg protein/lane) were mixed with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) and heated at 95 °C for 5 min. They were separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with 40-150 g/L gradient polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes using the semidry electron transfer system (ATTO Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The membranes were incubated in 50 g/L SM-PBS-T at room temperature for 30 min (blocking step). Proteins on PVDF membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight: anti-GA-AGE antibody (1:1000), neutralized anti-GA-AGE antibody (1:1000), rabbit monoclonal [ERP3953] anti-HSP90α antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom; 1:2000; ab109248), rabbit polyclonal anti-HSP70 antibody (Abcam; 1:8000; ab94368), rabbit polyclonal anti-HSP27 antibody (Abcam 1:1000; ab1428), rabbit polyclonal anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology Japan K.K.; 1:1000; #9661), and mouse monoclonal [6C5] anti-GA-3 phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH) antibody (Abcam; 1:10000; ab8245). PVDF membranes were washed four times with 5.0 g/L SM-PBS-T and incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. The secondary antibodies were the following: HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Dako; 1:2000; REF0448), which was used to analyze GA-AGEs, HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; 1:5000; Product Number 31458), and HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; 1:2000; Product Number 31432). Band densities were measured as well as SB. When the detection of HSP90β was performed, proteins on PVDF membranes were probed with a mouse monoclonal [5G4] anti-HSP90β antibody (Abcam; 1:20000; ab119833) and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Then, proteins on PVDF were incubated in the secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. The anti-GAPDH antibody was used after the target antibody was removed by the Western re-probe kit.

Estimation of molecular weight of proteins

The molecular weight (MW) of proteins detected by (WB) was calculated based on a single logarithmic chart used by HRP-MM.

Statistical analysis

Stat Flex (ver. 6) software (Artech Co., Ltd.) was used for statistical analyses. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. When statistical analyses were performed on the data, except those in the experiment of GA-AGEs-BSA, significant differences in the mean of each group were assessed by a One-Way Analysis of Variance. We then used a Dunnett’s test for an analysis of variance. A statistical analysis of the data shown in the experiment of GA-AGEs-BSA was performed using the Student’s t-test. In each statistical analysis, P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Effects of GA treatment on cell viability and the production of GA-AGEs in PANC-1 cells

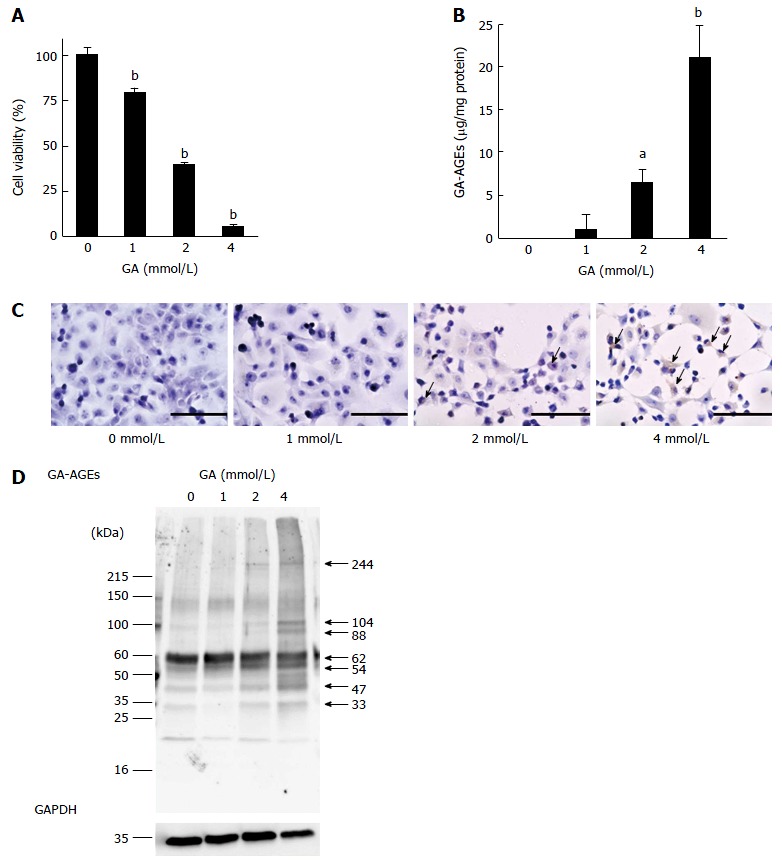

We employed the WST-8 assay to examine the viability of PANC-1 cells treated with GA for 24 h. The viability of PANC-1 cells decreased in a GA dose-dependent manner. PANC-1 cell viability was approximately 40% with a 2 mmol/L GA treatment and decreased to almost 0% with a 4 mmol/L GA treatment (Figure 1A). We then measured intracellular GA-AGEs using an SB analysis and detected these products after 24 h. The production of GA-AGEs in PANC-1 cells increased in a GA dose-dependent manner (Figure 1B). Cells treated with 2 and 4 mmol/L GA produced 6.4 and 21.2 μg/mg protein of GA-AGEs, respectively. A large amount of GA-AGEs was produced in cells treated with 4 mmol/L GA. The results of immunostaining using an anti-GA-AGE antibody are consistent with the SB results; namely, the production of GA-AGEs in PANC-1 cells increased in a GA dose-dependent manner (Figure 1C). Moreover, we observed areas lacking cells in 2 and 4 mmol/L GA treatment samples. The area without cells was larger in the samples treated with 4 mmol/L GA than in those treated with 2 mmol/L GA (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Analysis of cell viability, quantity of glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation-end products, immunostaining of glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation-end products, and molecular weight of glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation-end products in PANC-1 cells treated with glyceraldehyde for 24 h. A: Cell viability was assessed by the WST-8 assay. This assay was performed for three independent experiments. One assay was performed for n = 7. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 7); B: Slot blotting analysis of intracellular glyceraldehyde (GA)-derived advanced glycation-end products (GA-AGEs). Cell lysates (2.0 μg of protein/lane) were blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The amount of GA-AGEs was calculated based on a standard curve for GA-AGEs-BSA. Slot blotting was performed for three independent experiments. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3); C: Immunostaining of GA-AGEs in PANC-1 cells. Cells were treated with 0, 1, 2 and 4 mmol/L GA. The arrow indicates the area stained by the anti-GA-AGE antibody. The scale bar represents 200 μm; D: Western blotting analysis of intracellular GA-AGEs in PANC-1 cells. Cell lysates (15 μg of proteins/lane) were loaded on a 40-150 g/L polyacrylamide gradient gel. Proteins on the PVDF membrane were probed with anti-GA-AGE and anti-GA-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibodies. The molecular weight of GA-AGEs was calculated based on a single logarithmic chart used by the molecular marker. GAPDH was used as the loading control. WB was performed for two independent experiments. A and B: P values were based on Dunnett’s test. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01 vs control.

Investigation of GA-AGEs

We performed a WB analysis on GA-AGEs. We compared the bands on PVDF membranes incubated with an anti-GA-AGE antibody and those on PDVF membranes incubated with a neutralized anti-GA-AGE antibody. The bands of GA-AGEs were confirmed and their MWs were analyzed. Bands were clearly observed at 33, 47, 54, 62, 88, 104, and 244 kDa (Figure 1D and Figure S1). The results of the WB indicated the production of GA-AGEs, and this was supported by the results of SB and immunostaining using an anti-GA-AGE antibody. The density of the GA-AGEs bands appeared to increase in a GA dose-dependent manner.

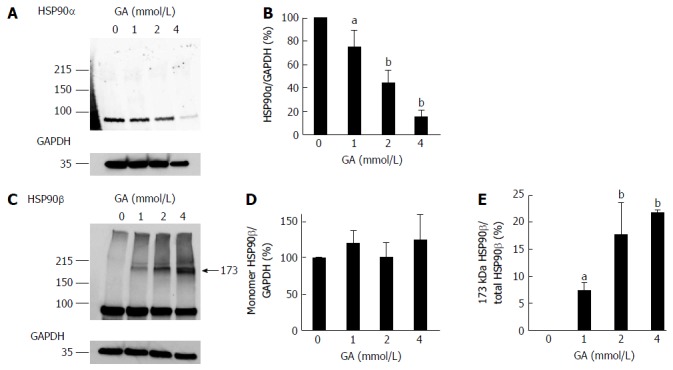

Effects of GA treatment on HSP90α and HSP90β

Expression levels of HSP90α and HSP90β, which are cell death-associated proteins that suppress the production of cleaved caspase-3 from pro-caspase-3, were analyzed by WB. Expression levels of the monomer HSP90α decreased in a GA dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A, B, and Figure S2), whereas that of the monomer HSP90β did not (Figure 2C, D and Figure S3). We only detected the 173 kDa band of HSP90β in PANC-1 cells treated with GA and the 173 kDa HSP90β/total HSP90β ratio increased in a GA dose-dependent manner (Figure 2C and E).

Figure 2.

Western blotting analysis of HSP90α and HSP90β. PANC-1 cell lysates (15 μg of proteins/lane) were loaded on a 40-150 g/L polyacrylamide gradient gel. A: Proteins on the polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane were probed with anti-HSP90α and anti-GAPDH antibodies; B: Expression levels of HSP90α were normalized with GAPDH; C: Proteins on the PVDF membrane were probed with anti-HSP90β and anti-GAPDH antibodies. A band of 173 kDa HSP90β only appeared in PANC-1 cells treated with GA; D: Expression levels of the monomer HSP90β were normalized with GAPDH; E: The 173 kDa HSP90β/total HSP90β ratio. A and C: Western blotting was performed for three independent experiments. GAPDH was used as the loading control; B, D and E: Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). P values were based on Dunnett’s test. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01 vs control. GA: Glyceraldehyde.

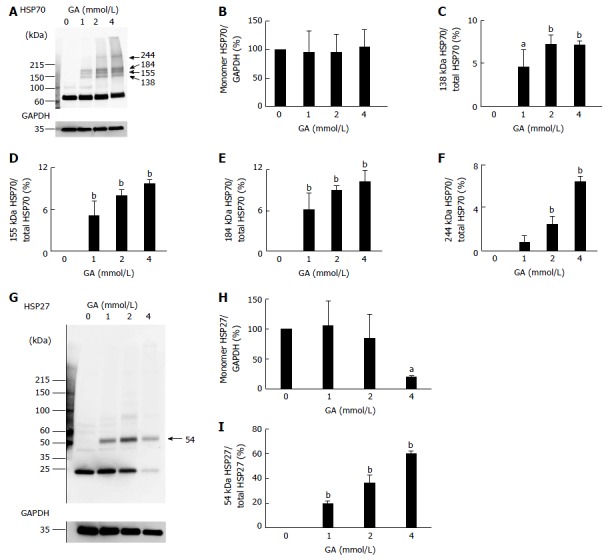

Effects of GA treatment on HSP70 and HSP27

WB analysis of HSP70 and HSP27, which suppress the production of cleaved caspase-3, HSP90α, and HSP90β, was performed. Expression of the monomer HSP70 was not affected by GA treatment, similar to HSP90β expression (Figure 3A, B and Figure S4). Furthermore, 138, 155, 184, and 244 kDa HSP70s were detected in PANC-1 cells treated with GA (Figure 3A, C-F). The ratio of these HSP70 bands to total protein (HSP70/total HSP70) increased in a GA dose-dependent manner (Figure 3A, C-F). However, expression of the monomer HSP27 was only affected by the 4 mmol/L GA treatment, in which it decreased to 20% (Figure 3G, H and Figure S5). The band of 54 kDa HSP27 was only detected in cells treated with GA and the 54 kDa HSP27/total HSP27 ratio increased in a GA dose-dependent manner (Figure 3G and I). The quantity of total HSP27 in cells treated with 4 mmol/L GA was 52% when compared to control cells (Figure 3G).

Figure 3.

Western blotting analysis of HSP70 and HSP27. PANC-1 cell lysates (15 μg of proteins/lane) were loaded on a 40-150 g/L polyacrylamide gradient gel. A: Proteins on the polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane were probed with anti-HSP70 and anti-GA-3 phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH) antibodies. We found four high-molecular-weight (HMW) complexes of HSP70s only in PANC-1 cells treated with GA. Their MWs were 138, 155, 184 and 244 kDa; B: Expression levels of the monomer HSP70 were normalized with GAPDH; C-F: The 138 kDa HSP70/total HSP70, 155 kDa HSP70/total HSP70, 184 kDa HSP70/total HSP70, and 244 kDa HSP70/total HSP70 ratios; G: Proteins on the PVDF membrane were probed with anti-HSP27 and anti-GAPDH antibodies. A HMW complex with a MW of 54 kDa appeared only in PANC-1 cells treated with GA; H: Expression levels of the monomer HSP27 were normalized with GAPDH; I: The 54 kDa HSP27/total HSP27 ratio; A and G: WB was performed for three independent experiments. GAPDH was used as a loading control. B-F, H, I: Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). P values were based on Dunnett’s test. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01 vs control. GA: Glyceraldehyde.

Effects of GA treatment on cleaved capsase-3

The production of cleaved caspase-3 was analyzed with WB. Two types of Jurkat cell lysates were used to confirm that the anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody was functioning correctly: one lysate was treated with cytochrome c, whereas the other was not. Cleaved caspase-3 was not detected in any of the lanes (0-4 mmol/L) of PANC-1 cell lysates (Figure 4 and Figure S6).

Figure 4.

Western blotting analysis of cleaved caspase-3. PANC-1 cell lysates (15 μg of protein/lane) and Jurkat cell lysates (10 μg of protein/lane) were loaded on a 40-150 g/L polyacrylamide gradient gel. Proteins on the PVDF membrane were probed with anti-cleaved caspase-3 and anti-GA-3 phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH) antibodies. U: The lysate of Jurkat cells not treated with cytochrome c. T: The lysate of Jurkat cells treated with cytochrome c. Western blotting was performed for three independent experiments. GAPDH was used as a loading control. GA: Glyceraldehyde.

Proliferation of PANC-1 cells treated with GA-AGEs-BSA

PANC-1 cells were treated with 10 and 20 μg/mL of the non-glycated control BSA and GA-AGEs-BSA and then incubated for 24 h. Cell proliferation was analyzed using the WST-8 assay. The proliferation of PANC-1 cells treated with 10 and 20 μg/mL GA-AGEs-BSA was 27% and 34% greater than that of control cells, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Analysis of the proliferation of PANC-1 cells treated with glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation-end products-bovine serum albumin. PANC-1 cells were treated with 10 and 20 μg/mL of non-glycated control BSA and glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation-end products-bovine serum albumin (GA-AGEs-BSA) to then be incubated for 24 h. This assay was performed for two independent experiments. One assay was performed for n = 7. Cell proliferation was assessed by the WST-8 assay. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 7). P values were based on the Student’s t-test. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01 vs control.

DISCUSSION

PDAC accounts for approximately 90% of pancreatic malignancies[3]. Another characteristic of pancreatic cancer is its association with T2DM, which increases the risk of pancreatic cancer by more than 50%[5,6]. However, the mechanisms through which T2DM promotes pancreatic cancer currently remain unknown. We consider PDAC to be one of the lifestyle-related diseases associated with T2DM. Therefore, we hypothesized that hyperglycemia, a characteristic of T2DM, contributes to the promotion of PDAC. Because hyperglycemia induces the production of AGEs, we herein investigated if AGEs promote PDAC. However, it is important to note that not all AGEs promote PDAC. GA-AGEs generated from GA (glucose and fructose metabolites) have been implicated in the pathogeneses of various diseases such as insulin resistance, hypertension, diabetic complications, dementia, cardiovascular diseases, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer[7-12]. Therefore, we designated these GA-AGEs as TAGE[7-12]. In the present study, we hypothesized that GA-AGEs contribute to the development of PDAC.

To prove this hypothesis, PANC-1 cells were incubated in high glucose medium, a model of T2DM blood, and treated with GA. We speculated that GA promotes the proliferation of PANC-1 cells. But our results indicated cell viability decreases in a GA dose-dependent manner (Figure 1A). In contrast, SB analysis revealed that the production of GA-AGEs in cells increased in a GA dose-dependent manner (Figure 1B), results that were supported by those obtained using immunostaining (Figure 1C). Our results indicated that cell death is induced by the production of GA-AGEs. Using WB, which was performed using an anti-GA-AGE antibody, we detected 7 clear bands (Figure 1D). Because the production of GA-AGEs induced cell death, we investigated cell death-associated proteins in PANC-1 cells. These proteins were selected from those with MWs of 33, 47, 54, 62, 88, 104, and 244 kDa, which represent bands that were detected by WB analysis with an anti-GA-AGE antibody (Figure 1D). As a result, HSP90 was selected as a candidate cell death-associated protein. This protein has been identified as an apoptosis-associated HSP in PANC-1 cells[14,15]. A previous study reported that GA-AGEs were generated from heat shock cognate 70 (Hsc70), which belongs to the HSP family, following treatment with GA in the human hepatic cancer cell line, Hep3B[16]. Apoptosis was induced in Hep3B cells because GA-AGEs induced the formation of Hcs70 aggregates, and therefore failed to exert its normal functions.

Furthermore, AGEs were shown to be produced from HSP27 by methylglyoxal, one of the by-products of glycolysis[17-19]. HSP90, HSP70, and HSP27 are important proteins in cell death because they suppress the production of cleaved caspase-3 from pro-caspase-3 in PANC-1 cells[14,15,20,21]. Because bands at 70 and 27 kDa were not clearly detected by WB with an anti-GA-AGE antibody (Figure 1D), we only targeted HSP90.

WB results on HSP90α revealed that band density decreased in a GA dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A and B). This result generally suggests a decrease in the expression or increase in the degradation of HSP90α; however, another possibility is that the GA derivative of HSP90α was generated and the epitope for the anti-HSP90α antibody lost its function.

However, the expression of the monomer HSP90β, an isomer of HSP90α[22], was not affected; furthermore, the 173 kDa HSP90β was detected and increased in a GA dose-dependent manner (Figure 2C-E). We were unable to confirm GA-induced modifications in the monomer HSP90β, but predicted that the 173 kDa HSP90β is a GA-AGEs-mediated homodimer. If two HSP90βs combine with GA-derived modifications, their MW is expected to be approximately 176 kDa, which is close to 173 kDa. Because we confirmed the presence of a 173 kDa HSP90β, we hypothesized that the HMW complexes with GA-derived modifications in HSP70 and HSP27 (e.g., GA-AGEs-mediated dimers, trimers, and tetramers) may be generated and contain GA-AGEs detectable by WB (Figure 1D). These HMW complexes were generated in PANC-1 cells treated with GA (Figure 3A, C-G, I). We considered 138, 155, 184, and 244 kDa HSP70s to be the dimers and trimers containing the homo and hetero types with GA-AGEs-mediated aggregation. The possibility of 244 kDa HSP70 being GA-AGEs is greater than that of another HMW complexes of HSP70s because a clear band for 244 kDa GA-AGEs was detected in the WB analysis (Figure 1D).

Because a 54 kDa band was clearly detected by WB analysis using an anti-GA-AGE antibody, the 54 kDa HSP27 was likely to be a GA-AGE (Figure 1D). Moreover, we predict that 54 kDa HSP27 is a homodimer with GA-AGEs-mediated aggregation because its MW was twice that of a monomer. Monomers and total HSP27 only decreased with the 4 mmol/L GA treatment (Figures 3G-I). The production of GA-AGEs in PANC-1 cells treated with 4 mmol/L GA were greater than that seen with any other GA dose, and most cells died. A decrease in monomers and total HSP27 may have been induced due to the abnormal cellular conditions caused by the excessive amount of GA-AGEs. Previous studies identified a number of different routes for cell death in PANC-1 cells including apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy[23-25]. HSP90, HSP70, and HSP27 regulate apoptosis by suppressing the production of cleaved caspase-3[14,15,20,21]. We were interested in the decrease in the normal monomer HSP90α and increase in the HMW complex of HSP90β, HSP70, and HSP27 after GA treatment. Although we speculated an increase in the production of cleaved caspase-3, this was not observed in PANC-1 cells, which generated intracellular GA-AGEs (Figure 4).

PANC-1 cells that produced GA-AGEs may have undergone a non-apoptotic form of cell death. Cell death may induce the release of intracellular GA-AGEs into conditioned medium. Live cells may also secrete GA-AGEs. After analyzing intracellular GA-AGEs and proteins associated with cell death, we hypothesized that extracellular GA-AGEs promote the growth of pancreatic cancer cells. The proliferation of PANC-1 cells was promoted by both 10 and 20 μg/mL of GA-AGEs-BSA, a model of secreted or released GA-AGEs (Figure 5). This phenomenon may also be associated with the receptor for AGEs (RAGE) and induced via the GA-AGEs-RAGE system. Several reports have already been published on the proliferation of Hep3B, HepG2, IL90, and HuH7 cells, which are derived from human liver cancer cell lines, treated with GA-AGEs[26-28]. Although GA-AGEs-BSA did not promote the proliferation of Hep3B and HepG2 cells, it may promote the proliferation of IL90 and HuH7 cells. RAGE was previously shown to be weakly expressed in Hep3B and HepG2 cells[26]; therefore, the induction of proliferation did not appear to be induced via the GA-AGEs-RAGE system. On the other hand, high expression levels of RAGE in IL90 cells have already been demonstrated by WB[27]. RAGE was found to be weakly expressed in HuH7 and HepG2 cells; however, RAGE expression levels on the membrane of HuH7 cells were approximately 4-fold those of HepG2 cells[28]. RAGE expression levels on HuH7 cell membranes may be sufficient to promote cell proliferation through the GA-AGEs-RAGE system.

RAGE has been detected in human pancreatic cancer cell lines[29,30]. WB revealed high expression levels of RAGE in PANC-1 and MIA-PaCa-2 cells, and low levels in BxPC-3 cells[30]. GA-AGEs-BSA may promote the proliferation of PANC-1 as well as IL90 and HuH7 cells through the GA-AGEs-RAGE system.

In conclusion, intracellular and extracellular GA-AGEs induced PANC-1 cell death and proliferation, respectively. This suggests that, although intracellular GA-AGEs induce pancreatic cancer cell death, their secretion and release may induce the proliferation of other pancreatic cancer cells.

In this investigation, we did not examine GA-AGEs; however, we consider the monomer HSP90α, monomer HSP90β, and HMW complexes of HSPs to be GA-AGEs. However, two recent studies identified GA-AGEs generated by Hsc70 and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M in Hep3B cells treated with GA or fructose[16,31].

If the monomers and aggregates of HSPs are identified as GA-AGEs in the future, this indicates that GA-AGEs were first identified in human pancreatic ductal carcinoma cells. Identifying intracellular GA-AGEs will reveal the mechanism of cell death. In addition, GA-AGEs secreted or released into the conditioned medium of cultured PANC-1 cells, which generate intracellular GA-AGEs, may demonstrate that extracellular GA-AGEs promote cancer. If the mechanism through which T2DM promotes PDAC relies on GA-AGEs as key factors, the current research on drug therapy for PDAC may change[1,32].

COMMENTS

Background

Pancreatic cancer is a highly lethal disease and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) accounts for approximately 90% of malignancies in the pancreas. On the other hand, the incidence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is increasing worldwide each year, and this condition may result in lifestyle-changing complications. Type 2 DM (T2DM) has been shown to increase the risk of pancreatic cancer by more than 50%. However, the mechanism promoting PDAC in the pancreas of T2DM patients has not yet been elucidated.

Research frontiers

The authors focused on hyperglycemia and how it induces the production of advanced glycation-end (AGEs). AGEs are formed by a Maillard reaction, a nonenzymatic reaction that occurs between the ketones or aldehyde of sugars and the amino group of proteins. The authors have previously identified AGEs derived from glyceraldehyde (GA-AGEs); therefore, they designated GA-AGEs as toxic AGEs (TAGE) because of their cytotoxicity and involvement lifestyle-related diseases. In this study, the authors examined the production of intracellular GA-AGEs in the human pancreatic cancer cell lines, PANC-1, and the proliferation of PANC-1 cells treated with GA-AGEs-bovine serum albumin (GA-AGEs-BSA).

Innovations and breakthroughs

This study reported the production of GA-AGEs in PANC-1 cells treated with GA, which resulted in cell death. HSP90β, HSP70, and HSP27, which are cell-death associated proteins, generated HMW complexes that could predict GA-AGEs-mediated aggregation. Moreover, GA-AGEs-BSA, a model of extracellular GA-AGEs, promoted proliferation of PACN-1 cells.

Applications

The experimental data can be used to analyze the relationship between T2DM and PDAC via the production of GA-AGEs. Studying the production and effects of intracellular and extracellular GA-AGEs in pancreatic cancer cells can be used in further investigation to develop PDAC therapies.

Terminology

AGEs derived from GA, a glucose/fructose metabolism intermediate, also known as GA-AGEs. They designated GA-AGEs as TAGE because of their cytotoxicity and involvement in insulin resistance, hypertension, diabetic complications, cardiovascular diseases, dementia, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer.

Peer-review

The manuscript is well written, the study was conducted properly, and the conclusion is supported by the data presented.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study does not need to be reviewed and approved by the Kanazawa Medical University because the experiment only used an established cell line (PANC-1) and the cell line was not genetically modified.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: April 10, 2017

First decision: April 26, 2017

Article in press: June 19, 2017

P- Reviewer: Kin T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Shimasaki T, Yamamoto S, Ishigaki Y, Takata T, Arisawa T, Motoo Y, Tomosug N, Minamoto T. Identification and functional analysis of an EMT-accelerating factor induced in pancreatic cancer cells by anticancer agent. Suizo. 2016;31:76–84. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wada K, Takaori K, Traverso LW, Hruban RH, Furukawa T, Brentnall TA, Hatori T, Sano K, Takada T, Majima Y, et al. Clinical importance of Familial Pancreatic Cancer Registry in Japan: a report from kick-off meeting at International Symposium on Pancreas Cancer 2012. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:557–566. doi: 10.1007/s00534-013-0611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinnett-Smith J, Kisfalvi K, Kui R, Rozengurt E. Metformin inhibition of mTORC1 activation, DNA synthesis and proliferation in pancreatic cancer cells: dependence on glucose concentration and role of AMPK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;430:352–357. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeuchi M. Serum Levels of Toxic AGEs (TAGE) May Be a Promising Novel Biomarker for the Onset/Progression of Lifestyle-Related Diseases. Diagnostics (Basel) 2016;6:pii: E23. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics6020023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bobrowski A, Spitzner M, Bethge S, Mueller-Graf F, Vollmar B, Zechner D. Risk factors for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma specifically stimulate pancreatic duct glands in mice. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giovannucci E, Michaud D. The role of obesity and related metabolic disturbances in cancers of the colon, prostate, and pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2208–2225. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeuchi M, Yamagishi S. TAGE (toxic AGEs) hypothesis in various chronic diseases. Med Hypotheses. 2004;63:449–452. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takino J, Nagamine K, Hori T, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takeuchi M. Contribution of the toxic advanced glycation end-products-receptor axis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2459–2469. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i23.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koriyama Y, Furukawa A, Muramatsu M, Takino J, Takeuchi M. Glyceraldehyde caused Alzheimer’s disease-like alterations in diagnostic marker levels in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13313. doi: 10.1038/srep13313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi M, Takino J, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takata T, Ueda T, Tsutsumi M, Hyogo H, Yamagishi S. Involvement of the TAGE-RAGE system in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Novel treatment strategies. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:880–893. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i12.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeuchi M, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takino J, Ueda T, Tsutsumi M. Toxic AGEs (TAGE) theory in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and ALD. Int J Diabetes Clin Res. 2015;2:4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeuchi M, Sakasai-Sakai A, Takata T, Ueda T, Takino J, Tsutsumi M, Hyogo H, Yamagishi S. Serum levels of toxic AGEs (TAGE) may be a promising novel biomarker in development and progression of NASH. Med Hypotheses. 2015;84:490–493. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi M, Makita Z, Bucala R, Suzuki T, Koike T, Kameda Y. Immunological evidence that non-carboxymethyllysine advanced glycation end-products are produced from short chain sugars and dicarbonyl compounds in vivo. Mol Med. 2000;6:114–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jolly C, Morimoto RI. Role of the heat shock response and molecular chaperones in oncogenesis and cell death. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1564–1572. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.19.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaworek J, Leja-Szpak A. Melatonin influences pancreatic cancerogenesis. Histol Histopathol. 2014;29:423–431. doi: 10.14670/HH-29.10.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takino J, Kobayashi Y, Takeuchi M. The formation of intracellular glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end-products and cytotoxicity. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:646–655. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schalkwijk CG, van Bezu J, van der Schors RC, Uchida K, Stehouwer CD, van Hinsbergh VW. Heat-shock protein 27 is a major methylglyoxal-modified protein in endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1565–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakamoto H, Mashima T, Yamamoto K, Tsuruo T. Modulation of heat-shock protein 27 (Hsp27) anti-apoptotic activity by methylglyoxal modification. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45770–45775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells-Knecht KJ, Zyzak DV, Litchfield JE, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Mechanism of autoxidative glycosylation: identification of glyoxal and arabinose as intermediates in the autoxidative modification of proteins by glucose. Biochemistry. 1995;34:3702–3709. doi: 10.1021/bi00011a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M, Yu X, Guo H, Sun L, Wang A, Liu Q, Wang X, Li J. Bufalin exerts antitumor effects by inducing cell cycle arrest and triggering apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:2461–2471. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu W, Li J, Wu S, Li S, Le L, Su X, Qiu P, Hu H, Yan G. Triptolide cooperates with Cisplatin to induce apoptosis in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2012;41:1029–1038. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31824abdc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang H, Duan B, He C, Geng S, Shen X, Zhu H, Sheng H, Yang C, Gao H. Cytoplasmic HSP90α expression is associated with perineural invasion in pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:3305–3311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larocque K, Ovadje P, Djurdjevic S, Mehdi M, Green J, Pandey S. Novel analogue of colchicine induces selective pro-death autophagy and necrosis in human cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malsy M, Gebhardt K, Gruber M, Wiese C, Graf B, Bundscherer A. Effects of ketamine, s-ketamine, and MK 801 on proliferation, apoptosis, and necrosis in pancreatic cancer cells. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:111. doi: 10.1186/s12871-015-0076-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huggett MT, Tudzarova S, Proctor I, Loddo M, Keane MG, Stoeber K, Williams GH, Pereira SP. Cdc7 is a potent anti-cancer target in pancreatic cancer due to abrogation of the DNA origin activation checkpoint. Oncotarget. 2016;7:18495–18507. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takino J, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M. Glycer-AGEs-RAGE signaling enhances the angiogenic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma by upregulating VEGF expression. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1781–1788. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i15.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwamoto K, Kanno K, Hyogo H, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, Tazuma S, Chayama K. Advanced glycation end products enhance the proliferation and activation of hepatic stellate cells. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:298–304. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakuraoka Y, Sawada T, Okada T, Shiraki T, Miura Y, Hiraishi K, Ohsawa T, Adachi M, Takino J, Takeuchi M, et al. MK615 decreases RAGE expression and inhibits TAGE-induced proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5334–5341. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i42.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takada M, Hirata K, Ajiki T, Suzuki Y, Kuroda Y. Expression of receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and MMP-9 in human pancreatic cancer cells. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:928–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takada M, Koizumi T, Toyama H, Suzuki Y, Kuroda Y. Differential expression of RAGE in human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1577–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takino J, Nagamine K, Takeuchi M, Hori T. In vitro identification of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-related protein hnRNPM. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1784–1793. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i6.1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takata T, Ishigaki Y, Shimasaki T, Tsuchida H, Motoo Y, Hayashi A, Tomosugi N. Characterization of proteins secreted by pancreatic cancer cells with anticancer drug treatment in vitro. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:1968–1976. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]