Abstract

Rural mammography screening remains suboptimal despite reimbursement programs for uninsured women. Networks linking non-clinical community organizations and clinical providers may overcome limited delivery infrastructure in rural areas. Little is known about how networks expand their service area. To evaluate a hub-and-spoke model to expand mammography services to 17 rural counties by assessing county-level delivery and local stakeholder conduct of outreach activities. We conducted a mixed-method evaluation using EMR data, systematic site visits (73 interviews, 51 organizations), 92 patient surveys, and 30 patient interviews. A two-sample t test compared the weighted monthly average of women served between hub- and spoke-led counties; nonparametric trend test evaluated time trend over the study period; Pearson chi-square compared sociodemographic data between hub- and spoke-led counties. From 2013 to 2014, the program screened 4603 underinsured women. Counties where local “spoke” organizations led outreach activities achieved comparable screening rates to hub-led counties (9.2 and 8.7, respectively, p = 0.984) and did not vary over time (p = 0.866). Qualitative analyses revealed influence of program champions, participant language preference, and stakeholders’ concerns about uncompensated care. A program that leverages local organizations’ ability to identify and reach rural underserved populations is a feasible approach for expanding preventive services delivery.

Keywords: Rural, Breast cancer, Health disparities, Health services delivery, Mixed methods, Program implementation

BACKGROUND

Despite the Affordable Care Act’s emphasis on preventive services, many rural communities face significant challenges in linking women to the full continuum of breast cancer screening services (e.g., screening and diagnostic mammography, breast biopsy, and referral to cancer treatment) [1]. Rural populations, when adjusted for age, are more likely than their urban counterparts to lack health insurance [2], such that women are significantly less likely to meet guidelines for the receipt of preventive services such as mammograms. Further, there are limited numbers of primary care providers and specialists to care for patients spread across vast geographic areas [3]. Many providers have limited financial and staff resources to meet the requirements needed to participate in federal programs like the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), a federal-state partnership to increase access to screening among underinsured and uninsured women [2, 4, 5]. As a result of these factors, penetration of the NBCCEDP program is low and access is poor in rural areas, particularly in Texas [6].

In 2009, Moncrief Cancer Institute (Moncrief) created the Breast Screening and Patient Navigation (BSPAN) program, a virtually integrated network of primary care providers, radiologists, and surgeons to increase access through coordinated outreach, patient navigation, and reimbursement of local providers for screening and diagnostic services delivered to underserved women in North Texas [7]. Building upon its success, Moncrief expanded BSPAN in 2012 to a total of 17 rural counties by transitioning to a decentralized “hub-and-spoke” delivery model that partnered local providers and organizations as “spokes” with Moncrief, the program “hub” [3]. Spoke organizations with knowledge of local healthcare systems and populations and the capacity to implement outreach and navigation components were trained to implement those program aspects [8]. The hub continued to deliver outreach and navigation in counties with limited capacity. Across all counties, the hub continued to implement centralized reimbursement utilizing its existing state NBCCEDP contract.

Here, we evaluated BSPAN’s hub-and-spoke model by (1) quantifying women who received mammography services at the county level and (2) qualitatively assessing spoke organizations’ ability to conduct outreach activities. We hypothesized that our regional hub-and-spoke delivery model was successful if the program served equivalent or greater numbers of women per month irrespective of whether outreach activities were conducted by spoke organizations or Moncrief, the program hub. We used county-level service data and qualitative interviews and site visits with spoke partners and hub staff to elucidate programmatic challenges in using this model to expand delivery of services.

METHODS

Setting

This study was conducted in 17 counties—an area of ~14,800 square miles with an estimated 74,000 screen-eligible women [9, 10]. Counties are heterogeneous with respect to population size [9], degree of rurality [11], and health-related infrastructure (e.g., mammography availability) [12–15], based on currently available federal and state data (Table 1).

Table 1.

Rural county characteristics and screening activity by outreach approach

“Hub-led” outreach counties

“Hub-led” outreach counties  County no. 10 (a high pop. spoke-led county)

County no. 10 (a high pop. spoke-led county)  Spoke-led” outreach counties

Spoke-led” outreach counties

aUS Census, ACS 5-Year Estimates

bUS Census, Urban Area Delineation Program; “none” indicates Census term “no urbanized population”

cHealth Provider Shortage Area (HPSA), US Health Resources Services Administration

dU.S. News and World Report

eAmerican College of Radiology

Program components

To expand access to the BSPAN program across 17 rural counties, the hub conducted a multilevel, multistep assessment process in each county and determined whether any organization in that county had the capacity to conduct outreach or patient navigation (details about the capacity assessment process reported elsewhere [16]). The process integrated publicly available county data (Table 1), hub staff’s assessment of potential spoke organizations, and self-assessments by potential spoke organizations.

In counties with an organization able to lead outreach (“spoke-led”), the hub communicated with the individual in the spoke organization chosen to lead outreach activities. In counties where no local organization had the capacity to conduct outreach, the hub led all outreach activities. Outreach included advertising upcoming screening dates and locations through mass media (radio, local county newspapers) and small media (posters in local businesses, print and email flyers/newsletters distributed by prominent organizations such as the Chamber of Commerce). For all 17 counties, the hub mailed handouts to each county’s Indigent Healthcare Program Office for distribution to residents. The handouts, available in both English and Spanish, included a toll-free phone number and information about the availability of fully funded mammograms for uninsured women. The toll-free number linked callers to schedulers and nurse navigators at the hub who assisted with scheduling mammography and follow-up services either at brick-and-mortar facilities (“in-house”) or on mobile mammography vans, at a date and location of the callers’ convenience.

Mixed-methods program evaluation design

Following Fetters and colleagues [17], we employed a convergent mixed-methods design collecting quantitative and qualitative data in parallel, during program implementation, for a cross-informed analysis [18].

Quantitative data collection and analysis

Our evaluation team worked with hub staff to create and implement a customized electronic medical record database to track the program participants’ sociodemographic (e.g., race/ethnicity, county of residence, insurance status) and clinical service (e.g., screening and diagnostic mammography, ultrasound, biopsy) data. Each contact with program participants was recorded in the database in real time by navigation staff. Database-derived reports provided ongoing assessments of key program metrics, e.g., time to clinical resolution, proportion uninsured, proportion baseline mammography, etc.

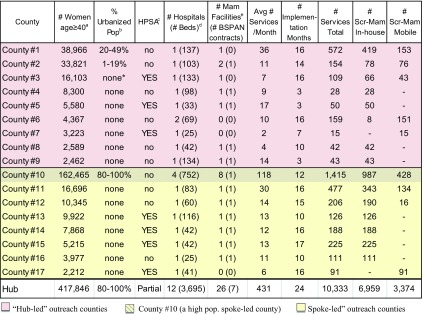

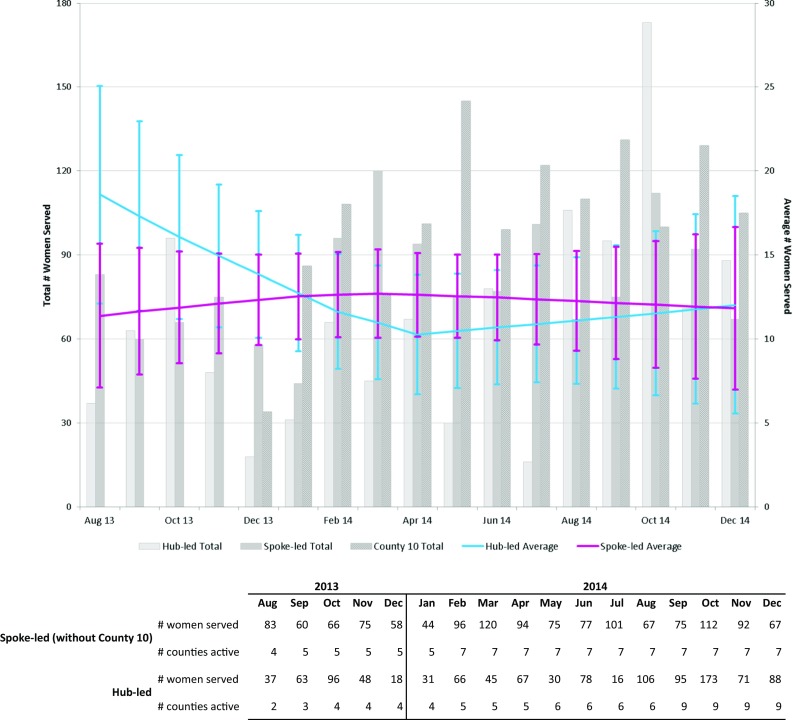

To examine our hypothesis that the number of women served was equivalent between spoke- and hub-led counties, our primary outcome was the average number of women served per month over a 2-year study period (Jan. 2013–Dec. 2014), stratified by outreach approach (hub- vs. spoke-led). Because counties implemented program activities at different time points, first, we tallied the number of women served in a particular county and divided that total by the number of months of program implementation in that county (Table 1, range 3–17 months). Then, we summed the monthly averages for all of the hub-led counties and divided by 24 months (the study period) to calculate a weighted average of women served per month. We calculated a similar weighted measure for spoke-led counties; however, we reported average number of women served for county no. 10 separately because the eligible population is significantly larger and more urbanized compared to the other 16 counties (Table 1). We conducted a two-sample t test to examine whether the overall weighted average number of women served differed between the hub- and spoke-led counties, excluding county no. 10 (Table 2). For both spoke- and hub-led counties, we plotted actual and average number of women served per month by outreach approach (Fig. 1) and used the nonparametric trend test to examine whether there is a time trend in the average number of women served over the study period.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of women served, by outreach approach (Jan 2013—Dec 2014; N = 4,603)

| “Hub-led” outreach counties (n = 9) | “Spoke-led” outreach counties (n = 7) | County 10 (high pop. spoke-led) | p valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population served | ||||

| Volume | n = 1243 | n = 1380 | n = 1980 | – |

| No. of women/month, mean (SD; range)b | 8.7 (9.7; 1.0–24.7) | 9.2 (7.0; 1.5–21.0) | 56.1 | 0.984 |

| Age | % | % | % | |

| ˂40 years | 11.1 | 9.9 | 12 | 0.007 |

| 40–49 years | 37.3 | 37.5 | 47.0 | |

| 50–64 years | 45.8 | 49.4 | 39.3 | |

| ≥65 years | 5.8 | 3.3 | 1.7 | |

| Race/ethnicity c | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 68.1 | 69.6 | 28.6 | 0.462 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2.0 | 2.0 | 11.6 | |

| Hispanic (any race) | 28.1 | 26.1 | 55.7 | |

| Poverty/insurance | ||||

| ≤200 % FPL | 84.2 | 86.2 | 92.2 | 0.034 |

| Uninsured | 78.2 | 88.1 | 95.9 | <0.0001 |

| Screening status | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 90.8 | 90.3 | 85 | 0.689 |

| Symptomatic | 9.3 | 9.7 | 15.0 | |

| Baseline mammogram | 59.3 | 59.8 | 59.8 | 0.798 |

| “Hub-led” outreach counties (n = 9) | “Spoke-led” outreach counties (n = 7) | County 10 (high pop. spoke-led) | ||

| Population served | ||||

| Volume | n = 1243 | n = 1380 | n = 1980 | |

| No. of services/month, mean | 9 | 9.5 | 58.7 | |

| Age | % | % | % | |

| ˂40 years | 11.1 | 9.9 | 12 | |

| 40–49 years | 37.3 | 37.5 | 47.0 | |

| 50–64 years | 45.8 | 49.4 | 39.3 | |

| ≥65 years | 5.8 | 3.3 | 1.7 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 68.1 | 69.9 | 28.6 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2 | 2 | 11.6 | |

| Hispanic (any race) | 28.1 | 26.1 | 55.7 | |

| Poverty/insurance | ||||

| ≤200 % FPL | 84.2 | 86.2 | 92.2 | |

| Uninsured | 78.2 | 88.1 | 95.9 | |

| Screening status | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 90.8 | 90.3 | 85 | |

| Symptomatic | 9.3 | 9.7 | 15.0 | |

| Baseline mammogram | 59.3 | 59.8 | 59.8 | |

aTwo sample t test for average women/month and Pearson Chi-square for categorical variables; comparisons do not include county 10

bWeighted averages were computed by summing the number of women served in a particular county and dividing that total by the number of months of program implementation in that county; monthly averages for all hub-led counties were summed and divided by 24 months (the study period); similarly, monthly averages for all spoke-led counties (without county 10) were summed and divided by 24 months

cMultiracial, other, and unknown races not shown for each group: 1.8, 2.3, and 4.1 %, respectively

Fig 1.

Screening services by “hub-led” and “spoke-led” counties by month, 2013–2014

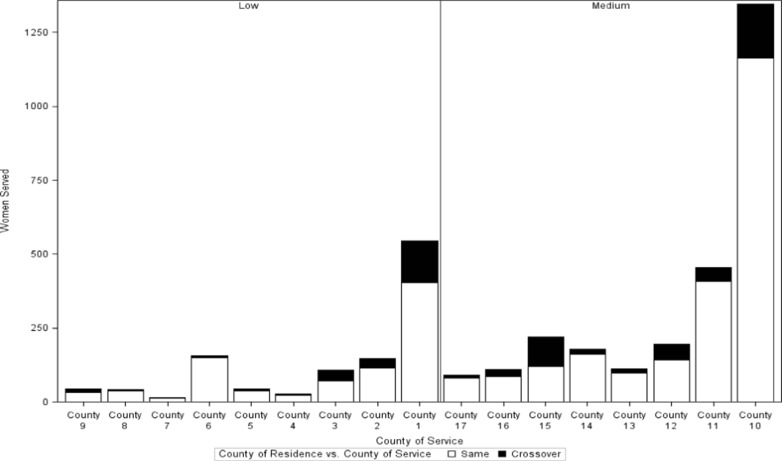

Finally, we used Pearson chi-square test to compare sociodemographic data between hub- and spoke-led counties (Table 2). To describe the extent that women traveled to other counties within the BSPAN network to access services, we plotted the number of women served by the participant’s county of residence (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

County crossover for services by “hub-led” and “spoke-led” counties, 2013–2014

Qualitative data collection and analysis

To qualitatively evaluate the BSPAN program, we purposefully selected 6 of the 17 total counties by (1) outreach approach (4 “spoke-led”, 2 “hub-led”) and (2) geography (county’s proximity to hub). We conducted multiple site visits and interviews with spoke organization staff (e.g., radiology techs, managers, nurses) as well as key medical and community leaders (e.g., physician at a non-profit clinic, African-American clergy). Over an 8-month period, researchers interviewed 73 individuals staffing or leading 51 clinical and community-based organizations in the 6 selected counties. We collected documents describing outreach activities from the hub and spoke organizations to identify, for example, key partners and strategies. Additionally, researchers surveyed 92 BSPAN participants regarding the timeliness and quality of patient care, of which 30 participated in longer, open-ended phone interviews, ranging from 30 to 60 min. Of the 30 interviews, 6 (20%) were conducted with cancer-positive participants, and 12 (41%) were conducted in Spanish by participant request.

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim; those conducted in Spanish were transcribed verbatim and then translated into English. We imported both English and Spanish transcripts into NVivo to preserve the original communication and enable non-Spanish-speaking researchers to participate in the analysis. Additionally, we imported ~90 pages of researcher field notes, including annotated reflections on interviews, brief communications, and fieldwork observations and notes from events. Three qualitative scientists (RH, SI, SL) conducted thematic analysis in NVivo (9.0 QSR Australia). We began with a deductive coding scheme that focused on individual- and community-level factors influencing program implementation [3, 19, 20], building on our capacity assessment tool [16] and conceptual model of the screening process [21]. In biweekly meetings, we undertook inductive analysis to identify and interpret emergent themes. Triangulating across our different data sources, we revised the coding scheme in an iterative process. In our final codebook, we jointly identified common themes, grouping 43 codes into 7 distinct themes, reflecting substantive evidence across different participant groups and different sites. In this manuscript, we present the three themes most relevant to elucidating the program context implicated by the statistical analyses of service delivery outcomes.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents individual county characteristic and screening activity; the column “number of implementation months” reflects each county’s participation period. Most counties had fewer than 20,000 women eligible for screening, no urbanized population, one hospital, and one mammography facility. Three of the nine hub-led and four of eight spoke-led counties qualified as a healthcare provider shortage area (HSPA). We formed contracts with local radiology providers in 12 of the 14 counties with a mammography facility. Two counties, lacking a mammography facility, relied solely on a mobile mammography van, eight counties relied solely on in-house providers, and nine counties used both in-house and mobile mammography providers.

Quantitative evaluation of service delivery at the county level

The average number of services provided per month ranged from 2 to 36 in hub-led counties and from to 6 to 118 in spoke-led counties. For 2 two-year evaluation period (Jan. 2013–Dec. 2014), the program screened 4603 women, diverse in age, race/ethnicity, poverty level, insurance, and screening status, across 17 rural counties.

Table 2 aggregates sociodemographic data of women served by outreach approach, (hub-led, spoke-led, county no. 10). An anomaly among the 17 counties, county no. 10, is reported separately because it is, by far, the most urbanized, most populous (~162,465 screen-eligible women), and most well-equipped (8 screening facilities). Given these characteristics, county no. 10, not surprisingly, reported the highest average volume of women screened per month (n = 118).

Excluding county no. 10, spoke-led outreach counties delivered services to a greater proportion of low-income and uninsured women than hub-led counties (p = 0.03 and p < 0.0001, respectively). We found spoke-led outreach counties served slightly fewer Hispanic women (~2 %), although this was not statistically significant. Hub-led outreach counties delivered services to older (≥65) and younger (<40) women when compared to spoke-led outreach counties (p = 0.007). Overall, our hub-and-spoke model served an average of 9.2 women per month in the spoke-led counties and 8.7 women for hub-led counties (p = 0.984).

As depicted in Fig. 1, the average number of women served per month in the hub-led and spoke-led counties did not vary over the 2-year study period (p = 0.866). We found that many women crossed county borders (range 4–37 %) to access services in a county other than their county of residence (Fig. 2).

Qualitative assessment of hub- and spoke-led outreach activities

The BSPAN hub-and-spoke model allowed each spoke provider to determine how they preferred to organize the timing of appointments for women eligible for services through the hub’s NBCCEDP contract. At the same time, the centralized toll-free number provided a funnel for all spoke outreach activities to channel interested participants through a common master calendar of dates and locations across all 17 counties to increase the overall program efficiency and maximize convenience for participating women.

Analyses of qualitative data collected during program implementation highlighted the importance of (1) program champions, (2) participants’ desire to communicate with providers in their preferred language, and (3) clinical stakeholders’ concerns about demand for uncompensated care.

Champions

Many individuals in the spoke organizations acted as “program champions” by using their knowledge of the local context to facilitate outreach activities beyond the training provided by the hub. These champions raised awareness of the program through more diverse channels available in local communities. Champions included clergy at primarily African-American and Latino churches, community organizers for local initiatives like back-to-school supply donations, breast cancer survivors, and local healthcare providers. For example, champions distributed flyers in businesses serving low-income populations like laundromats and bodegas. A Spanish-speaking radiologist, providing services in multiple counties, accelerated outreach activities by instructing her staff to share program information with patients at all of the facilities where she practiced, some of which were in counties outside of the BSPAN service area. As a result, the hub received calls from residents in counties where BSPAN program had not yet been implemented.

Champions in spoke organizations who mobilized their social networks to promote the program were particularly effective in reaching target communities in need (underinsured and uninsured, Hispanic and Spanish-speaking women) and building grassroots enthusiasm for the program. However, dependence on a champion could also reduce the spoke organization’s activities should that individual become indisposed. For example, in one of the counties furthest from the hub, a nurse and long-time champion of breast cancer screening led both outreach and patient navigation from the county’s sole mammography facility. During an unexpected 4-month absence, that county conducted only a handful of screenings as they were unable to enlist additional support from other local organizations.

Program participants’ preference for language concordance

Spanish-speaking participants repeatedly reported passing word of the program using informal social networks within immigrant communities where women were eager to learn which clinics employed Spanish-speaking providers. Participants were willing to cross county lines and travel longer distances to receive care in their preferred language. Indeed, several participants reported crossing over to county no. 15, where a participating primary care clinic employed a Spanish-speaking nurse, having heard positive evaluations of the provider from friends and family.

Clinical stakeholders’ concerns about uncompensated care

The hub sometimes struggled to identify local mammography facilities willing to contract to provide services to the uninsured and to conduct outreach activities. For example, several of the county subsidy programs were not well-positioned to actively promote services for preventive care to indigent populations across their county, in part, because that might involve referrals to competing hospitals. Several clinical partner organizations were more familiar with commercially insured populations than the underinsured and uninsured women BSPAN hoped to identify and serve. With varied eligibility requirements, services, and funding caps, county Indigent Health Programs were largely oriented to dealing with opportunistic cases in order to minimize subsidies for uncompensated care at their respective county hospitals. Stakeholders at one hospital located near a low-income Latino community seemed wary of creating an increased demand for uncompensated care beyond screening, and expressed reluctance to systematically invite the underserved. As a result, the hub contracted with a different hospital whose area population was less indigent and ethnically diverse, potentially reducing BSPAN’s impact among underserved women in that county.

DISCUSSION

Our analyses demonstrated there was no difference in capacity to deliver services between hub-led and spoke-led counties. The average number of women served per month did not differ between counties for which the hub- versus the spokes-led outreach, as assessed by a two-sample t test, and there was no change in the average number of women served over time. We found similar uptake for breast cancer screening services among rural, uninsured women, despite notable county heterogeneity across our catchment area. Qualitative data revealed that variation in the crossover of women (Fig. 2) and actual numbers of women served per month reflect contextual issues: (1) participant motivation to crossover to other counties and receive services from providers willing to communicate in Spanish and (2) outreach efforts that leverage program champions’ knowledge and grassroots connections.

A significant percentage of women opted to receive services outside of their home county. Among the counties with the highest crossover rate, counties no. 1, 2 and 10 are closer geographically to the urban metroplex. Women may have crossed county borders to access services in larger metropolitan areas, which feature a broader selection of providers and institutions. Rates of crossover may also reflect appointment locations convenient to places of employment rather than residence. Crossover to semiurban counties (no. 1, no. 2) may reflect intermediate convenience for women residing in more rural counties seeking provider choice but not wanting to travel all the way into the urban hub.

We observed the highest rate of crossover in county no. 15, located on the geographic periphery of the BSPAN service area. The observed volume could be explained by women residing outside of BSPAN counties seeking access to fully funded screening services. Also, outreach strategies initiated in one county may have reached women in other counties. For example, many organizations extend their newsletter circulation to neighboring counties for marketing purposes. Radio advertising from a station based in one town nonetheless captures listenership across multiple adjacent counties. This increased program visibility overall but complicated our ability to directly correlate the number of women served with outreach activities conducted in that county.

Hub-led outreach efforts were largely mass and small media-driven, focusing on radio and newspaper advertising, and to a lesser extent, posters and handouts mailed to prominent local organizations like the county hospital. This type of mass marketing can be particularly effective when coupled with local events like Breast Cancer Awareness month, which may be reflected in the increase in numbers of women served in October (Fig. 1). In contrast, spoke-led outreach efforts were often focused on more grassroots efforts at a local level: in-person communications, network-building activities, and advertising through popular local business. Once key partner organizations had been identified, local champions acted to both expand and to diversify the BSPAN outreach strategy in their local areas [22, 23].

We found that Spanish-speaking communities, in particular, leveraged communication about service access through social networks that crossed county boundaries [16, 24, 25]. Indeed, the availability of Spanish-language provider staff was commonly shared among women, resulting, as reported, in a large volume of women who preferred Spanish-language care-seeking services in county 15. As a result, spoke outreach reached local population niches through community members sharing information about BSPAN with their informal social networks [26]. Local champions leveraged social networks to reach large numbers of community members; acting as opinion leaders, they also helped foster trust among other program partners, streamlining coordination with other stakeholders for promotional events [27]. The balance between centralized functions of scheduling or reimbursement and outreach tailored to local settings enabled the program hub to accommodate partner organization independence while retaining a key level of centralization necessary to broaden overall program uptake and increase individual opportunities for women to receive screening services.

In principle, BSPAN contracts with spoke county-based providers sought to create new avenues for underinsured and uninsured women to access funded services. Yet, an organizational expertise in clinical care did not necessarily translate to optimal outreach [28, 29]. The reluctance of one county hospital to adopt new outreach plans to increase access to mammography among uninsured women may have reflected downstream financial concerns with uninsured patients who may rely on the hospital for services other than for reimbursable breast cancer screening services [30, 31]. Further, the BSPAN expansion protocol relied on voluntary collaboration. Although many individuals were eager to leverage existing professional and/or personal networks to help promote the program, some potential champions who were engaged in unrelated employment were, as a result, more limited in their ability and willingness to undertake program activities outside of their work time.

Our findings demonstrate the value of a mixed-method design to evaluate the expansion of a rural prevention service program. Overall, the program expansion was highly successful: the number of women interested in receiving services greatly exceeded program expectations. That resulting rapid increase in demand had consequences that will require further study to help advance the science of scaling up and further rationalize models of preventive service delivery [8]. Previous studies have demonstrated that program designs able to accommodate flexibility during implementation can enhance service uptake among rural-residing women [7, 32, 33]. Our experience supports such findings. The program expansion strategy prioritized implementation in those counties that were initially perceived to have greater resources, strengthening operations in an initial round of expansion and allowing more time to establish relationships in other new counties. Consequently, the program “launched” earlier in counties determined to be capable of spoke-led outreach than in counties that would rely on the hub for both outreach and navigation. It is possible that this bias may have contributed to lower screening volumes seen in hub-led outreach counties. Moreover, increased demand for scheduling and navigation, also, may have reduced hub capacity to conduct more in-depth outreach in those counties where the hub was intended to lead.

Limitations

Contextual issues shape outreach efforts and explain county-level variation in screening. The BSPAN hub-and-spoke model was premised on the idea that spoke partner organizations could assume a greater share of program responsibilities to enable the hub to rationalize deployment of resources and increase reach among local populations in need. Clinical infrastructure, then, is a critical element of county capacity. But while it is necessary, clinical infrastructure is an insufficient determinant of overall program success. Indeed, available clinical infrastructure contributes to county-level variation in screening by shaping outreach efforts. That is, a spoke county’s mode of screening within the program—specifically whether through BSPAN mobile mammography or contracted brick-and-mortar local provider—contributed to the nature of outreach activities conducted. Thus, our finding of county-level variation in the number of women served was also partly influenced by the local clinical capacity.

Adapting to the extraordinary volume required unanticipated system upgrades of the clinical scheduling and navigation database, as well as hiring and training of additional staff at the hub. While the hub operations team managed to accommodate increased demand for scheduling and nurse-assisted navigation, documentation and quality monitoring of outreach activities were more inconsistent [8]. Strict adherence to network standards remains a challenge when expanded geography and limited resources restrict the number of organizations with which to partner [33]. Lastly, our study examined organizational efforts to enhance rural outreach to underserved women. Our analysis did not examine the effects of well-documented patient-level barriers (cultural, psychosocial, structural) that may have hindered rural women’s ability to engage the BSPAN network [34–38].

CONCLUSIONS

Evolving to a regional hub-and-spoke model expanded access to NBCCEDP funding and increased Moncrief’s ability to leverage local knowledge, resources, and trusted community relationships [5]. While regional delivery networks may seek to expand their reach by partnering with rural community organizations, that expansion can be more effective when programs incorporate local knowledge of context and target population into outreach efforts.

Future analyses are needed to assess whether differences in county capacity influence time to screening completion and participant satisfaction with program services using this decentralized regional model, particularly exploring how systematic outreach efforts described may effectively counterbalance other patient-level barriers. The hub-and-spoke model for expanding and optimizing prevention services delivery should be evaluated in other settings and with other disease prevention campaigns.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sarah Masood and our BSPAN colleagues at Moncrief Cancer Institute for their ongoing collaboration and dedication to patients and our many county partner organizations.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding

This study was funded by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (PP120097-Lee), which underwrote the BSPAN clinical screening and navigation program. Additional support was provided by the National Cancer Institute (5P30CA142543) to the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center and National Institutes of Health (NCATS UL1TR001105) to the UT Southwestern Center for Translational Medicine. Drs. Lee and Tiro are also supported by funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R24 HS022418) to the UT Southwestern Center for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human rights

All study procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study in accordance with the research protocol approved by UT Southwestern’s Institutional Review Board (STU 022012-009 Lee).

Footnotes

Implications

• Policy: Preventive services delivery programs seeking to expand should leverage and partner with local organizations to conduct outreach in rural areas.

• Research: Local champions bring nuanced knowledge of the target population and tailoring county outreach efforts to local context increases program contact with underserved women.

• Practice: Mixed-methods evaluation research is useful to elucidate the influence of local context on program adoption and implementation.

References

- 1.Leung J, Mckenzie S, Martin J, Mclaughlin D. Effect of rurality on screening for breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing mammography. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14:2730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guy G, Jr, Tangka FL, Hall I, Miller J, Royalty J. The reach and health impacts of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(5):649–50. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0561-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inrig SJ, Tiro JA, Melhado TV, Argenbright KE, Craddock Lee SJ. Evaluating a de-centralized regional delivery system for breast cancer screening and patient navigation for the rural underserved. Texas Public Health Journal. 2014; 66(2): 25-34. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Howard D, Tangka FL, Royalty J, et al. Breast cancer screening of underserved women in the USA: results from the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 1998–2012. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(5):657–68. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0553-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslau ES, Rochester PW, Saslow D, Crocoll CE, Johnson LE, Vinson CA. Developing partnerships to reduce disparities in cancer screening. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard DH, Ekwueme DU, Gardner JG, Tangka FK, Li C, Miller JW. The impact of a national program to provide free mammograms to low-income, uninsured women on breast cancer mortality rates. Cancer. 2010;116(19):4456–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Argenbright K, Anderson RP, Senter M, Lee SJC. Breast screening and patient navigation in rural texas counties: strategic steps. Texas Public Health Journal. 2013; 65(1): 25.

- 8.Milat AJ, Bauman A, Redman S. Narrative review of models and success factors for scaling up public health interventions. Implementation Sci. 2015;10:113. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0301-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Census. American Community Survey (2009-13), 5-year estimates, by sex and age. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t (2013). Accessed 2/6/15.

- 10.American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts & figures 2013-2014. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042725.pdf (2014). Accessed 3/2/15.

- 11.US Census Bureau. Percent population residing in urbanized areas by county: 2010. Available at: http://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/thematic/2010ua/UA2010_UA_Pop_Map.pdf (2010). Accessed 2/8/16.

- 12.American College of Radiology. Accredited facility search. http://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Accreditation/Accredited-Facility-Search (2015). Accessed 3/2/15.

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services. Find shortage areas: HPSA by state & county. http://hpsafind.hrsa.gov/ (2014). Accessed 3/2/2015.

- 14.Texas Department of State Health Services. Breast and cervical cancer services clinic locator. Available at: https://www.dshs.state.tx.us/bccscliniclocator.shtm (2013). Accessed 11/13/13.

- 15.Texas Department of State Health Services. FY2015 breast and cervical cancer services contractors. Austin, TX; 2015.

- 16.Inrig SJ, Higashi RT, Tiro JA, Argenbright KE, Lee SJC. Assessing local county capacity to expand rural breast cancer screening and patient navigation: a decentralized hub-and-spoke model (BSPAN2). Austin, TX: Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), Innovations in Cancer Prevention and Research Conference; 2015.

- 17.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134–56. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nastasi BK, Hitchcock J, Sarkar S, Burkholder G, Varjas K, Jayasena A. Mixed methods in intervention research theory to adaptation. J Mix Method Res. 2007;1(2):164–82. doi: 10.1177/1558689806298181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5:1–11. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beaber EF, Kim JJ, Schapira MM, et al. Unifying screening processes within the prospr consortium: A conceptual model for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):djv120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Kemner AL, Donaldson KN, Swank MF, Brennan LK. Partnership and community capacity characteristics in 49 sites implementing healthy eating and active living interventions. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21:S27–S33. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palinkas L, Holloway I, Rice E, Fuentes D, Wu Q, Chamberlain P. Social networks and implementation of evidence-based practices in public youth-serving systems: a mixed-methods study. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):113. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mcguire AA, Garces-Palacio IC, Scarinci IC. A successful guide in understanding Latino immigrant patients: an aid for health care professionals. Fam Community Health. 2012;35(1):76–84. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3182385d7c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unger JB, Schwartz SJ. Conceptual considerations in studies of cultural influences on health behaviors. Prev Med. 2012;55(5):353–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suarez L, Ramirez AG, Villarreal R, et al. Social networks and cancer screening in four U.S. Hispanic groups. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schensul JJ. Community, culture and sustainability in multilevel dynamic systems intervention science. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43(3-4):241–56. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wayland C, Crowder J. Disparate views of community in primary health care: understanding how perceptions influence success. Med Anthropology Q. 2002;16(2):230–47. doi: 10.1525/maq.2002.16.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia Mosqueira A, Sommer B. Better outreach critical to ACA enrollment, particularly for Latinos. The Commonwealth Fund Blog, Jan 2016.

- 30.Leider JP, Castrucci BC, Russo P, Hearne S. Perceived impacts of health care reform on large urban health departments. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(1 Supp):S66–S75. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenbaum S. The ACA: Implications for the accessibility and quality of breast and cervical cancer prevention and treatment services. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(3):340–4. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bencivenga M, Derubis S, Leach P, Lotito L, Shoemaker C, Lengerich EJ. Community partnerships, food pantries, and an evidence-based intervention to increase mammography among rural women. J Rural Health. 2008;24(1):91–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talbot JA, Coburn A, Croll Z, Ziller E. Rural considerations in establishing network adequacy standards for qualified health plans in state and regional health insurance exchanges. J Rural Health. 2013;29(3):327–35. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramos AK, Correa A, Trinidad N. Perspectives on breast health education and services among recent Hispanic immigrant women in the Midwest: a qualitative study in Lancaster County, Nebraska. J Cancer Educ. 2015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Jones CE, Maben J, Lucas G, Davies EA, Jack RH, Ream E. Barriers to early diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer: a qualitative study of Black African, black Caribbean and white British women living in the UK. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gellert K, Braun KL, Morris R, Starkey V. The 'Ohana Day project: a community approach to increasing cancer screening. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(3):A99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexandraki I, Mooradian AD. Barriers related to mammography use for breast cancer screening among minority women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(3):206–18. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azami-Aghdash S, Ghojazadeh M, Sheyklo SG, et al. Breast cancer screening barriers from the womans perspective: a meta-synthesis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(8):3463–71. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.8.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]