Abstract

Inconsistent findings have reported on the inflammatory potential of diet and cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality risk. The aim of this meta-analysis was to investigate the association between the inflammatory potential of diet as estimated by the dietary inflammatory index (DII) score and CVD or mortality risk in the general population. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed and Embase databases through February 2017. All prospective observational studies assessing the association of inflammatory potential of diet as estimated by the DII score with CVD and all-cause, cancer-related, cardiovascular mortality risk were included. Nine prospective studies enrolling 134,067 subjects were identified. Meta-analyses showed that individuals with the highest category of DII (maximal pro-inflammatory) was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality (hazard risk [HR] 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06–1.41), cardiovascular mortality (RR 1.24; 95% CI 1.01–1.51), cancer-related mortality (RR 1.28; 95% CI 1.04–1.58), and CVD (RR 1.32; 95% CI 1.09–1.60) than the lowest DII score. More pro-inflammatory diets, as estimated by the higher DII score are independently associated with an increased risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer-related mortality, and CVD in the general population, highlighting low inflammatory potential diet may reduce mortality and CVD risk.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer are the leading causes of death worldwide1, 2. Chronic inflammation is linked to CVD and certain types of cancers3, 4. Low-grade inflammation is frequently caused by lifestyle or environmental factors. Diets play an important role in regulating chronic inflammation5, 6. Human diets can be grouped into pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory components. The anti-inflammatory diets have been described on the basis of a Mediterranean dietary pattern7, 8. Individuals with a high consumption of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, nuts, seeds, healthy oils, and fish may have a low risk of inflammation-related diseases9. Adopting healthy dietary pattern may be the first step in reducing inflammation-associated chronic diseases.

In order to assess the inflammatory potential of an individual’s diet, a novel dietary inflammatory index (DII) score was developed to estimate the inflammatory potential of nutrients and foods in the context of a dietary pattern10, 11. The DII distinguishes dietary patterns on a continuum from the maximal pro-inflammatory to maximal anti-inflammatory. A higher DII score indicates a more pro-inflammatory diet and a lower DII score represents a more anti-inflammatory diet. Ever since then, several studies12–21 have examined the association between inflammatory potential of diet as measured by the DII score and mortality or CVD risk in the general population. However, these studies yielded the conflicting results22. Moreover, the magnitude of the risk estimates varied considerably. To the best of our knowledge, no previous a systematic review or meta-analysis has addressed this issue. Therefore, we conducted this meta-analysis of available prospective studies to examine the association of pro-inflammatory diets as estimated by the higher DII score with CVD and mortality risk in the general population.

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

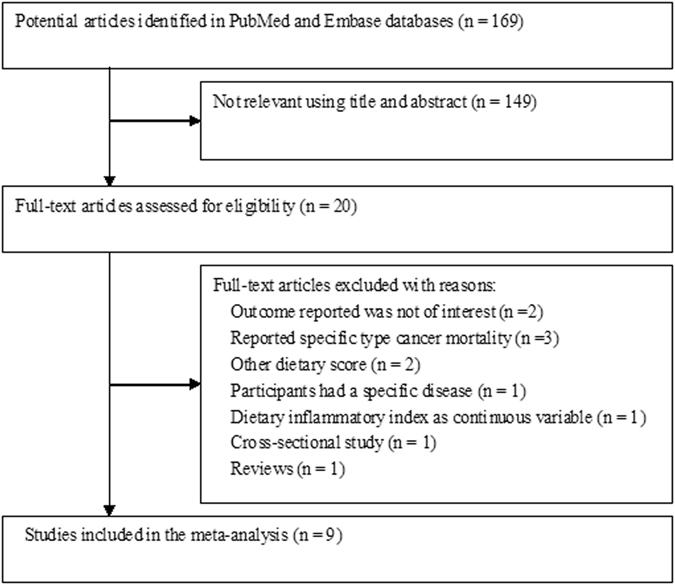

Briefly, a total of 179 relevant articles were identified with search terms. Of those, 20 were retrieved as full-text articles and 9 studies12–20 were finally included in the meta-analysis. The detailed study selection process is shown in Fig. 1. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. A total of 134,067 subjects were identified in these studies. The sample size of the included studies ranged from 1,363 to 37,525. Included studies were published between 2015 and 2017 and conducted in the United States13, 15, Spain17, 18, Sweden12, France14, 20, and Australia19. The follow-up duration ranged from 1.24 to 20.7 years. All nine studies achieved moderate to high methodological quality with a score from 6–8 stars and the mean NOS stars of the included studies was 7.0.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in meta-analysis.

| Study/year | Country | Design | Subjects (% female) | Mean age or range (years) | DII score evaluation | DII score Comparison | Events/number RR or OR (95% CI) | Follow-up (years) | Adjustment for covariates | NOS Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shivappa et al.12 | Sweden | Prospective population- based cohort | 33,747 (100) | 46 ± 9.9 | 27 food items using FFQ | Quintile 5 vs. 1 | Total death (7,095); | 15 | Age, energy intake, BMI, education, smoking status, PA, and alcohol intake. | 7 |

| 1.25 (1.07–1.47); | ||||||||||

| CV death (2,399); | ||||||||||

| 1.26 (0.93–1.70) | ||||||||||

| All cancer (1,996); | ||||||||||

| 1.25 (0.96–1.64) | ||||||||||

| Shivappa et al.13 | USA | Prospective cohort study | 37,525 (100) | 55–69 | 37 food items using FFQ | Quartile 4 vs. 1 | Total death (17,793) | 20.7 | Age, BMI, smoking, pack-years of smoking, HRT use, education, prevalent DM, prevalent hypertension, prevalent heart disease, prevalent cancer, total energy intake | 7 |

| 1.08 (1.03–1.13); | ||||||||||

| CV death (6,528); | ||||||||||

| 1.09 (1.01–1.18) | ||||||||||

| All cancer (5,044); | ||||||||||

| 1.08 (0.99–1.18) | ||||||||||

| Graffouillere et al.14 | France | Prospective cohort study | 8,089 (62.5) | 49.1 ± 6.0 | 36 food items using 24-h dietary records | Tertile 3 vs. 1 | Total death (207); | 1.24 | Age, sex, intervention group of the initial trial, number of 24-h dietary records, BMI, physical activity, smoking, education, family history of cancer or CVD in first-degree relatives, energy intake, and alcohol | 6 |

| 1.41 (0.97–2.04); | ||||||||||

| All cancer (123); | ||||||||||

| 1.83 (1.12–2.99) | ||||||||||

| Shivappa et al.15 | USA | Prospective cohort study | 12,438 (51.5) | 47.2 ± 19.1 | 27 food items using 24-h dietary records | Tertile 3 vs. 1; | Total death (2,795); | 11 | Age, sex, race, DM, hypertension, PA, BMI, poverty index, and smoking | 8 |

| 1.34 (1.19–1.51); | ||||||||||

| CV death (1,223); | ||||||||||

| 1.46 (1.18–1.81) | ||||||||||

| All cancer (615); | ||||||||||

| 1.46 (1.10–1.96) | ||||||||||

| O’Neil et al.16 | Australia | Prospective cohort study | 1,363 (0) | 59.2 ± 19.2/59 ± 19.2 | 22 food items using FFQ | Positive vs. negative DII (cutoff value) | CVD (76) | 5 | Age, DM, SBP, DBP, smoking history, PA, waist circumference, and total daily energy consumption. | 7 |

| 2.00 (1.01–3.96); | ||||||||||

| Ramallal et al.17 | Spain | Prospective cohort study | 18,974 (61) | 38 ± 12 | 28 food items using FFQ | Quartile 4 vs. 1 | CVD (117) | 8.9 | Age, sex, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, DM, smoking, family history of CVD, total energy intake, PA, BMI, education, other CVD, baseline special diet, snacking, average time sitting or spent watching television | 8 |

| 2.03 (1.06–3.88); | ||||||||||

| Garcia-Arellano et al.18 | Spain | Prospective cohort study | 7,216 (57.4) | 67 ± 6.2 | 32 food items using FFQ | Quartile 4 vs. 1 | CVD (277) | 4.7 | Age, sex, overweight/obesity, waist-to-height ratio, total energy intake, smoking, DM, hypertension, dyslipidemia, family history of premature CVD, PA, education, and stratified by intervention and center | m |

| 1.73 (1.15–2.60) | ||||||||||

| Vissers et al.19 | Australia | Prospective cohort study | 6,972 (100) | 52 ± 1.0 | 25 food items using FFQ | Positive vs. negative DII (cutoff value) | CVD (335) | 11 | Age, energy, DM, hypertension, smoking, education, menopausal status, HRT use, PA and alcohol consumption | 7 |

| 1.03 (0.76–1.42) | ||||||||||

| Neufcourt et al.20 | France | Prospective cohort study | 7,743 (42) | 51.9 ± 4.7 (men) and 47.1 ± 6.6 (women) | 36 food items using 24-h dietary records | Quartile 4 vs. 1 | CVD (292) | 11.4 | Sex, energy intake, supplementation group, 24-h records, education, marital status, smoking, PA, and BMI | 8 |

| 1.15 (0.79–1.68); |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; HR, hazard ratio; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CV, cardiovascular; DM, diabetes mellitus; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DII, dietary inflammatory index; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; PA, physical activity.

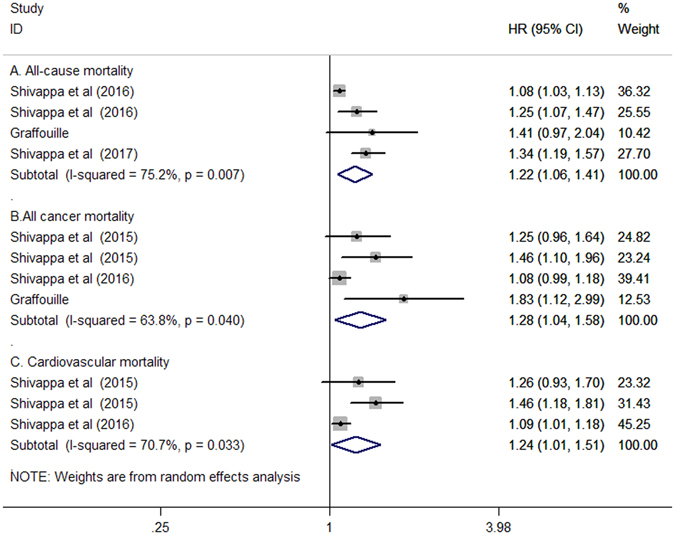

DII score and all-cause, cancer-related, cardiovascular mortality risk

Four studies12–15 involving 91,799 participants reported 27,890 all-cause mortality and 7,778 cancer-related mortality events. Three studies12, 13, 15 reported 10,150 cardiovascular mortality events from 83,710 participants. As shown in Fig. 2, when compared with those in the lowest DII category, participants in the highest category of DII (strongly pro-inflammatory) was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR 1.22; 95% CI 1.06–1.41; I2 = 75.2%, p = 0.007), cancer-related mortality (HR 1.28; 95% CI 1.04–1.58; I2 = 63.8%, p = 0.040), and cardiovascular mortality (HR 1.24; 95% CI 1.01–1.51; I2 = 70.7%, p = 0.033) in a random effect model.

Figure 2.

Forest plots showing HR with 95% CI of all-cause mortality (A), cancer-related mortality (B), and cardiovascular mortality (C) comparing the highest to the lowest dietary inflammatory index score.

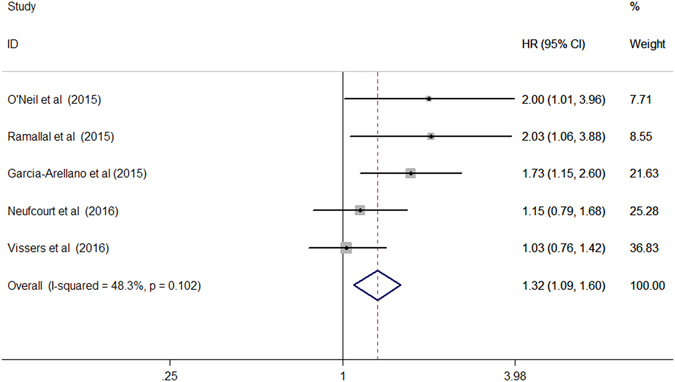

DII score and CVD risk

Five studies16–20 reported 1,097 cardiovascular mortality events from 42,268 participants. As shown in Fig. 3, participants in the highest category of DII (strongly pro-inflammatory) was associated with increased risk of CVD (HR 1.32; 95% CI 1.09–1.60; I2 = 48.3%, p = 0.102) compared with those in the lowest DII category in a fixed-effect model. When we changed to a random effect model, the pooled HR for participants in the highest category of DII was 1.41 (95% CI 1.06–1.86) than those in the lowest DII category.

Figure 3.

Forest plots showing HR with 95% CI of cardiovascular disease comparing the highest to the lowest dietary inflammatory index score.

Publication bias and sensitivity analyses

The small number of studies included in the individual outcome prevented us from conducting the publication bias using the Begg’s test and Egger’s test. Sensitivity analysis showed that individual study did not significantly impact on estimated overall effect size, indicating the reliability of our pooling results (data not shown).

Discussion

The main finding of this meta-analysis indicates that more pro-inflammatory diets, as estimated by the higher DII score are independently associated with the increased risk of CVD and all-cause, cancer-related, cardiovascular mortality in the general population. Participants with the highest category of DII (maximal pro-inflammatory) led to 32% higher risk of CVD, 22% higher risk of all-cause mortality, 28% higher risk of total cancer-related mortality, and 24% higher risk of cardiovascular mortality. These findings strengthen the idea that there are incremental disadvantages to increase the pro-inflammatory dietary ingredients.

There are several approaches to assess the dietary quality. The Healthy Eating Index23, Alternate Healthy Eating Index24, and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Score25 are the most frequently used diet indexes. All of these healthy dietary patterns were associated with a decreased risk of all-cause mortality24. In contrast to above dietary score, DII represents a new dietary quality index that specifically focuses on the dietary inflammatory potential. DII is a literature-derived population-based dietary score to assess a total of 45 food parameters including various macronutrients, vitamins, minerals, flavonoid, and specific food items11. A higher DII score is representative of more pro-inflammatory diets. In practice, DII score was computed from dietary intake assessed using a validated food frequency questionnaire or 24-h recall dietary records. Findings from the Energy Balance Study indicated that the DII score was associated with above mentioned dietary indices26.

Studies that not satisfied the inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis also investigated the association of dietary inflammatory potential with CVD or mortality risk. In the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study27, dietary inflammatory potential was assessed by means of an inflammatory score of the diet (ISD). Subjects with the highest ISD (more pro-inflammatory diet) had an HR of 1.42 for all-cause mortality, 1.89 for cardiovascular mortality, and 1.44 for cancer-related mortality. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III study28 showed that pro-inflammatory diet, as indicated by higher DII score, was associated with an increased risk of all-cause, CVD, all-cancer mortality among prediabetic patients. While in the NHANES study29, previously diagnosed CVD patients with the highest DII score significantly increased by 30% prevalence odds ratio of combined circulatory disorders, suggesting limiting pro-inflammatory diets may contribute to reduce the recurrence in these patients.

Chronic inflammation has a negative impact on the human body and health. The first step in the prevention and treatment of many chronic diseases is to follow a healthy dietary habit. Our meta-analysis reveals that limiting pro-inflammatory diets may be a healthy eating strategy to reduce CVD and mortality risk. An anti-inflammatory diet has beneficial effects on aging and health by slowing down telomere shortening21. In order to adopt a healthier diet, several anti-inflammatory foods including fruits, vegetables, fish or fish oil, walnuts, brown rice, and bulgur wheat should be part of the diet30. Moreover, avoid refined or processed foods and cut back on red meat or full-fat dairy foods are recommended.

This meta-analysis had some limitations. First, DII score was collected by self-report from 24-hour dietary recall or food frequency questionnaire, which carried an inherent degree of bias. Second, DII score was estimated at baseline and these data might change during the follow-up duration. However, adult dietary habits seem to relatively stable over time31, 32. Third, substantial heterogeneity was observed across studies pooling the mortality risk. Potential sources of heterogeneity included differences in the food items considered in the DII score, demographic characteristics, and follow-up duration. Fourth, the wide range of follow-up period (from 1.24 to 20.7 years) among the included studies was another limitation. However, sensitivity analyses showed no significant impact on the overall risk estimates when we excluded one study14 with the shortest follow-up duration. Finally, the majority of study participants were of European descent. Therefore, generalization of these findings to other ethnic populations should be taken with caution.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis suggests that more pro-inflammatory diets, as estimated by the DII score are independently associated with the increased risk of CVD and all-cause, cancer-related, cardiovascular mortality in the general population. However, whether promoting dietary patterns with low inflammatory potential could improve health status should be verified by more well-designed randomized controlled trials.

Methods

Search strategy

This meta-analysis followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement. A comprehensive literature search was carried out in PubMed and Embase through February 2017 with the following search terms in various combinations: (inflammatory potential of diet OR dietary inflammatory index OR pro-inflammatory diet OR anti-inflammatory diet) AND (cardiovascular disease OR mortality OR death OR survival) AND (prospective OR longitudinal OR follow-up). In order to find additional studies, we also manually searched the reference lists of all relevant articles.

Study selection

Studies were included if: (1) study participants were the general population; (2) study was prospective observational design; (3) the exposure of interest was the inflammatory potential of diets as estimated by DII score; and (4) reporting multivariable-adjusted risk estimates for the highest DII score (maximal pro-inflammatory diets) versus the lowest DII score (lowest pro-inflammatory diets) with respect to the all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer-related mortality, or CVD. Exclusion criteria were: (1) participants had a specific disease; (2) DII score as a continuous variable; (3) other inflammatory score of the diets as exposure; and (4) cross-sectional study, review or conference abstract.

Data extraction and quality assessment

For each included study, information on first author’s surname, publication year, study location, study design, sample sizes, percentage of women, mean age or age range, dietary assessment method, DII score comparison, number of events, most fully adjusted risk estimate, follow-up duration, and adjustment for variables. The methodological quality of included studies was assessed by a nine-star Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies33. The NOS is categorized into selection, comparability, and ascertaining of outcome. Studies with ≥7 stars were defined as high quality. Data extraction and quality assessment were performed independently by two authors. Any discrepancies between two authors were resolved by consensus.

Statistical analyses

All the analyses were conducted by the STATA software version 12.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). The multivariable-adjusted hazard risk ratio (HR) or odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was pooled for the highest versus the lowest DII score. The heterogeneity across studies was explored using the Cochrane Q and I2 statistic. If the Cochrane Q test ≤0.10 or I2 > 50%, the heterogeneity was considered as statistically significant34. Thus, a random effect model was selected to compute the summary effect; otherwise, a fixed-effect model was applied. Publication bias assessment with the Begg’s test35 and Egger’s test36 was planned when more than 10 studies were retrieved37. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by sequentially removed one study at a time.

Author Contributions

X.M. Zhong and L. Guo performed the literature research, study selection, and assessed the quality. L. Zhang and Y.M. Li made the statistical analysis. R.L. He drafted the manuscript. G.C. Cheng designed this study, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Xiaoming Zhong and Lin Guo contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearson TA, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107:499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Philip M, Rowley DA, Schreiber H. Inflammation as a tumor promoter in cancer induction. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14:433–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galland L. Diet and inflammation. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25:634–40. doi: 10.1177/0884533610385703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geraldo JM, Alfenas Rde C. Role of diet on chronic inflammation prevention and control - current evidences. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2008;52:951–67. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302008000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonaccio M, Cerletti C, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G. Mediterranean diet and low-grade subclinical inflammation: the Moli-sani study. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2015;15:18–24. doi: 10.2174/1871530314666141020112146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estruch R. Anti-inflammatory effects of the Mediterranean diet: the experience of the PREDIMED study. Proc Nutr Soc. 2010;69:333–40. doi: 10.1017/S0029665110001539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu X, Schauss AG. Mitigation of inflammation with foods. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:6703–17. doi: 10.1021/jf3007008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavicchia PP, et al. A new dietary inflammatory index predicts interval changes in serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. J Nutr. 2009;139:2365–72. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.114025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, Hussey JR, Hebert JR. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:1689–96. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013002115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shivappa N, Harris H, Wolk A, Hebert JR. Association between inflammatory potential of diet and mortality among women in the Swedish Mammography Cohort. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55:1891–900. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-1005-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shivappa N, et al. Association between inflammatory potential of diet and mortality in the Iowa Women’s Health study. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55:1491–502. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0967-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graffouillere L, et al. Prospective association between the Dietary Inflammatory Index and mortality: modulation by antioxidant supplementation in the SU.VI.MAX randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:878–85. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.126243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hussey JR, Ma Y, Hebert JR. Inflammatory potential of diet and all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III Study. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56:683–692. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-1112-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Neil A, et al. Pro-inflammatory dietary intake as a risk factor for CVD in men: a 5-year longitudinal study. Br J Nutr. 2015;114:2074–82. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515003815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramallal R, et al. Dietary Inflammatory Index and Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease in the SUN Cohort. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Arellano A, et al. Dietary Inflammatory Index and Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease in the PREDIMED Study. Nutrients. 2015;7:4124–38. doi: 10.3390/nu7064124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vissers LE, et al. The relationship between the dietary inflammatory index and risk of total cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease: Findings from an Australian population-based prospective cohort study of women. Atherosclerosis. 2016;253:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.07.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neufcourt L, et al. Prospective Association Between the Dietary Inflammatory Index and Cardiovascular Diseases in the SUpplementation en VItamines et Mineraux AntioXydants (SU.VI.MAX) Cohort. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002735. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Calzon S, et al. Dietary inflammatory index and telomere length in subjects with a high cardiovascular disease risk from the PREDIMED-NAVARRA study: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses over 5 y. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:897–904. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.116863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiz-Canela, M., Bes-Rastrollo, M. & Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A. The Role of Dietary Inflammatory Index in Cardiovascular Disease, Metabolic Syndrome and Mortality. Int J Mol Sci17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Guenther PM, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Development of the Healthy Eating Index-2005. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:1896–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwingshackl, L. & Hoffmann, G. Diet quality as assessed by the Healthy Eating Index, the Alternate Healthy Eating Index, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension score, and health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Acad Nutr Diet115, 780–800 e5 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Folsom AR, Parker ED, Harnack LJ. Degree of concordance with DASH diet guidelines and incidence of hypertension and fatal cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:225–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wirth MD, et al. Anti-inflammatory Dietary Inflammatory Index scores are associated with healthier scores on other dietary indices. Nutr Res. 2016;36:214–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agudo, A. et al. Inflammatory potential of the diet and mortality in the Spanish cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Spain). Mol Nutr Food Res (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Deng, F.E., Shivappa, N., Tang, Y., Mann, J.R. & Hebert, J.R. Association between diet-related inflammation, all-cause, all-cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality, with special focus on prediabetics: findings from NHANES III. Eur J Nutr (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Wirth MD, Shivappa N, Hurley TG, Hebert JR. Association between previously diagnosed circulatory conditions and a dietary inflammatory index. Nutr Res. 2016;36:227–33. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcason W. What is the anti-inflammatory diet? J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1780. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson FE, Metzner HL, Lamphiear DE, Hawthorne VM. Characteristics of individuals and long term reproducibility of dietary reports: the Tecumseh Diet Methodology Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:1169–78. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90018-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sijtsma FP, et al. Longitudinal trends in diet and effects of sex, race, and education on dietary quality score change: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:580–6. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.020719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wells, G. et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. (accessed May 6, 2014).

- 34.Higgins, J. P. T. & Green, S. e. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org. (accessed January 26, 2016).

- 35.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Schmid CH, Olkin I. The case of the misleading funnel plot. BMJ. 2006;333:597–600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7568.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]