Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is an important opportunistic pathogen in immunocompromised patients and a major cause of congenital birth defects when acquired in utero. In the 1990s, four chimeric viruses were constructed by replacing genome segments of the high passage Towne strain with segments of the low passage Toledo strain, with the goal of obtaining live attenuated vaccine candidates that remained safe but were more immunogenic than the overly attenuated Towne vaccine. The chimeras were found to be safe when administered to HCMV-seronegative human volunteers, but to differ significantly in their ability to induce seroconversion. This suggests that chimera-specific genetic differences impacted the ability to replicate or persist in vivo and the consequent ability to induce an antibody response. To identify specific genomic breakpoints between Towne and Toledo sequences and establish whether spontaneous mutations or rearrangements had occurred during construction of the chimeras, complete genome sequences were determined. No major deletions or rearrangements were observed, although a number of unanticipated mutations were identified. However, no clear association emerged between the genetic content of the chimeras and the reported levels of vaccine-induced HCMV-specific humoral or cellular immune responses, suggesting that multiple genetic determinants are likely to impact immunogenicity. In addition to revealing the genome organization of the four vaccine candidates, this study provided an opportunity to probe the genetics of HCMV attenuation in humans. The results may be valuable in the future design of safe live or replication-defective vaccines that optimize immunogenicity and efficacy.

Keywords: cytomegalovirus, recombinant, vaccine, attenuation, virulence

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infections are an important cause of birth defects among newborns infected in utero and of morbidity and mortality in transplant and AIDS patients. Despite receiving the US Institute of Medicine’s highest priority designation in 2000 (1), and after half a century of research, development of an HCMV vaccine remains an unmet medical need of considerable importance to public health.

Among the first HCMV vaccine candidates was the live attenuated strain Towne vaccine produced by >125 passages in cultured human fibroblasts (2). This vaccine has been administered safely to nearly 1,000 human subjects at doses as high as 3,000 plaque-forming units (pfu), and has never been recovered from an immunized subject, even following immune suppression (3–5). In contrast, the Toledo strain passaged only 4 or 5 times in cultured fibroblasts exhibited virulence characteristics in HCMV-seronegative volunteers at a dose of only 10 pfu (6), and was capable of superinfection, replicating, and persisting in the context of pre-existing natural immunity (6, 7). Although administration of Towne vaccine prior to renal transplantation reduced post-transplant HCMV-associated disease, it did not prevent HCMV infections (3), and it failed to protect immunocompetent mothers from acquiring HCMV infections from their children (8). These results suggest that the immunogenicity of the Towne vaccine may be overly attenuated due to mutations acquired during serial passage in vitro (9–11).

With the goal of increasing the immunogenicity of the Towne vaccine, four genetic chimeras were constructed by systematically replacing Towne genome segments with segments from Toledo (12). Each chimera was shown to be safe when administered at a dose of 1,000 pfu to healthy HCMV-seropositive human volunteers. However, failure to recover any chimera from blood, urine, or saliva following inoculation, combined with the inability of the chimeras to boost humoral or cellular immune responses, suggested that none retained the superinfection properties of the Toledo strain (12).

A phase 1 trial of the four chimeras in healthy HCMV-seronegative subjects was recently completed (13). Each vaccine was administered to a total of nine subjects, with groups of three subjects receiving doses of 10, 100, or 1,000 pfu by the subcutaneous route. There were neither local nor systemic reactions nor serious adverse events, and none of the subjects shed infectious virus in urine or saliva. In general, cellular and humoral immune responses were comparable to those reported previously for the Towne vaccine, and none of the chimeras appeared to be more virulent or immunogenic than the Towne vaccine. However, with regard to seroconversion, chimeras 2 and 4 were clearly more immunogenic than chimeras 1 or 3: seven of the nine subjects who received chimera 4 seroconverted, as did three of the nine subjects who received chimera 2, while only one of the nine subjects who received chimera 1 seroconverted, and none of the nine subjects who received chimera 3 seroconverted (13).

These results suggest that genetic differences among the four chimeras significantly impacted their ability to replicate or persist in vivo to an extent necessary to induce an antibody response. Although the approximate locations of junctions between Towne and Toledo sequences in the chimeras have been reported (12), the precise breakpoints and any spontaneous mutations that may have arisen during recombinant virus construction were unknown. Therefore, we determined the complete sequences of all four chimeras.

Table 1 summarizes genome information for the chimeras and complete (or substantially complete) Towne and Toledo sequences that were derived previously or during the present study. The Towne genomes represent two major variants, of which varS, in comparison with varL, has a large deletion at the right end of the UL region (commonly called UL/b’ (11)) associated with an inverted duplication of a sequence from the left end of UL (9). Passage of HCMV in cell culture is known invariably to result in mutation of RL13 and also of UL128, UL130, or UL131A (14–16), the latter three genes encoding subunits of a pentameric complex necessary for efficient entry of HCMV into cells of the epithelial, endothelial, or myeloid lineages (17–22). Towne is mutated in RL13 and UL130, as well as in UL1, UL40, and US1 (9, 10), and the form of varS from which the chimeras were derived is also mutated in UL36 (23). Toledo is mutated in RL13 and UL128 (the latter by the inversion of a large region of the genome) (11, 24, 25), as well as in UL9. Mapping the components of the chimeras was informed in particular by accessions FJ616285 and GQ121041 for Towne (9, 10) and accessions GU937742 and KY002201 for Toledo. GU937742 represents the standard form of Toledo from which the chimeras were derived (at passage 8), and KY002201 represents a variant (obtained via transfection of a Toledo DNA stock followed by plaque purification) that has a different mutation in gene RL13. The fact that more than one RL13 mutant was selected during isolation of Toledo is consistent with similar observations made with other strains, and indicates that adaptation of wild-type HCMV to cell culture involves a complex, gradual process of genetic selection (14–16). Thus, both Towne and Toledo apparently carried mutations that had accumulated due to passage in fibroblasts.

Table 1.

Partial and complete genome sequences of HCMV strains Towne and Toledoa.

| Strain | Genome | Accession | Size (bp) | Release date | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Towne | BAC varS | AC146851 | 229,483 | 14-Oct-2003 | (33) |

| Towne | BAC varS | AY315197 | 222,047 | 01-Dec-2003 | (34) |

| Towne | Virus varL | FJ616285 | 235,147 | 07-Feb-2009 | (9) |

| Towne | BAC varL | GQ121041 | 238,311 | 17-Jun-2009 | (10) |

| Towne | BAC mutant (UL96) varS | KF493877 | 233,028 | 18-Aug-2013 | (35) |

| Towne | Virus mutant (UL96) varS | KF493876 | 232,948 | 18-Aug-2013 | (36) |

|

| |||||

| Toledo | BAC | AC146905 | 226,889 | 21-Oct-2003 | (33) |

| Toledo | Virus | AH013698 | 158,133 | 08-Mar-2004 | (36) |

| Toledo | Virus | GU937742 | 235,404 | 10-Mar-2010 | Present work |

| Toledo | Virus variant | KY002201 | 235,681 | 15-Nov-2016 | Present work |

| Toledo | Virus mutant (RNA2.7) | KY002200 | 233,779 | 15-Nov-2016 | Present work |

|

| |||||

| Towne/Toledo | Virus chimera 1 | KX101021 | 235,882 | 08-Jun-2016 | Present work |

| Towne/Toledo | Virus chimera 2 | KX101022 | 234,441 | 08-Jun-2016 | Present work |

| Towne/Toledo | Virus chimera 3 | KX101023 | 235,354 | 08-Jun-2016 | Present work |

| Towne/Toledo | Virus chimera 4 | KX101024 | 236,269 | 08-Jun-2016 | Present work |

Genomes were sequenced as bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs), viruses, virus variants, virus mutants, or virus chimeras, and in varS or varL form for Towne. The two Towne BAC varS sequences describe the same BAC but differ in size because they lack different parts of the vector. The chimeras that had been used to inoculate seronegative human subjects (13) were amplified by passaging twice in MRC-5 human fibroblast cells, and virion DNA was isolated from culture supernatants as described previously (37). Sequence data were obtained for these and the other viruses examined in the present work by using the Illumina MiSeq platform, and assembled and validated as described previously (38). Additional information is available in the GenBank accessions.

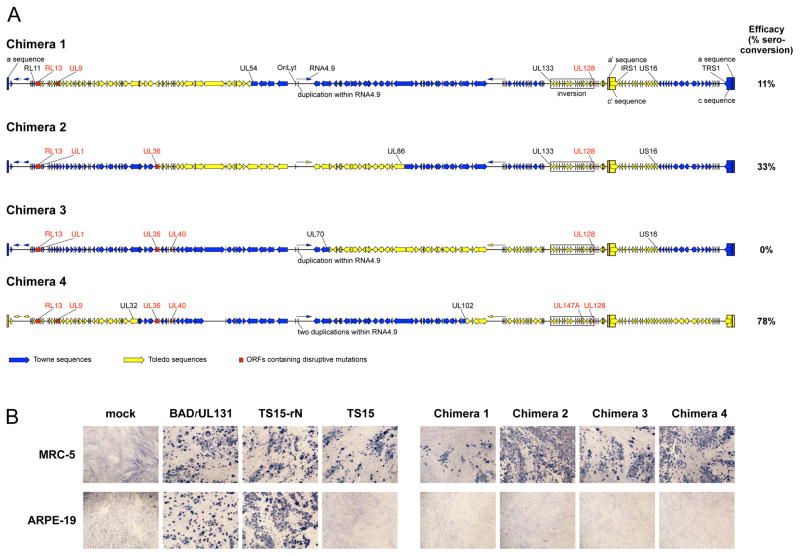

The genetic maps of the chimeras are shown in Figure 1A. The parental strains are both non-epitheliotropic and non-endotheliotropic due to the mutations disrupting expression of UL130 (Towne) or UL128 (Toledo) (10, 17, 26). The consequent failure to express a functional pentameric complex is speculated to contribute to attenuation of the Towne vaccine by limiting the range of host cell types available for replication in vivo, and to Towne’s insufficient efficacy, as the pentameric complex is an important immunogen for eliciting antibodies that neutralize the entry of HCMV into cells of the epithelial, endothelial, and myeloid lineages (22, 27–29).

Figure 1.

(A) Sequence-based genetic maps of the four Towne/Toledo chimera vaccine strains. Open arrows indicate open reading frames, and lines with arrowheads indicate noncoding RNAs. Tall rectangles indicate inverted repeats (a/a’ and c/c’), and these and other features (oriLyt, RNA4.9, IRS1, and TRS1) are labeled on chimera 1. Genes containing disrupting mutations are labeled in red, and genes located at breakpoints are labeled in black (these include UL36 in chimera 2). Additional differences among regions derived from the same original strain are not marked. These include a large noncoding deletion between US34A and TRS1 in chimera 2, a small noncoding deletion between UL150A and IRS1 in chimera 3, a short region of Towne sequence at the beginning of the Toledo a’ sequence in chimera 2 (probably as a result of recombination), a few differences in the lengths of noncoding G:C tracts, three substitutions in intergenic regions (UL102/UL103 and UL124/UL128 in chimera 1 and UL23/UL24 in chimera 4), one substitution in RNA5.0 in chimera 2, two synonymous substitutions in coding regions (UL10 and TRS1 in chimera 1), four nonsynonymous substitutions (UL11 and US10 in chimera 1, UL47 in chimera 2 and UL93 in chimera 4), and a small number (2–6 per genome) of nucleotide polymorphisms. The recombinational breakpoints in US16 in chimeras 1, 2, and 3 are located within a 255 bp sequence that is identical in Towne and Toledo. The values on the right indicate the relative immunogenicity levels of each chimera reported previously (13). (B) MRC-5 fibroblast or ARPE-19 epithelial cells were mock-infected or infected with equivalent amounts of the indicated viruses and after 4 d stained for HCMV immediate early proteins as described previously (27). BADrUL131 and TS15-rN are epitheliotropic variants of HCMV strains AD169 and Towne varS, respectively (26, 39), and TS15 is a non-epitheliotropic variant of Towne varS (10).

By design (12), all four chimeras contain Toledo UL/b’ and within this a disrupted copy of UL128. However, prior to the present study it was unclear whether chimeras 1 and 2 might contain an intact copy of UL128 within the upstream Towne sequences, potentially rendering them epitheliotropic and endotheliotropic. However, as the sequence data indicate that Towne UL128 is absent from all four chimeras, none of them is genetically capable of expressing a functional UL128 protein or pentameric complex, even though the UL130 and UL131A proteins, which contain neutralizing epitopes (30), may be expressed. Consistent with this, phenotypic analysis revealed that all four chimeras fail to enter ARPE-19 epithelial cells efficiently (Figure 1B and (31)). By extension, the inability to express the pentameric complex is consistent with the phase 1 trial findings that the chimera vaccines induced neutralizing titers to entry into epithelial cells similar to those of Towne and significantly lower than those induced by natural infection (13). In addition to the previously recognized mutations in the parental strains, the sequences revealed three novel mutations. The first disrupts UL147A in chimera 4, the second is a short duplication within the Towne-derived noncoding RNA4.9 in chimeras 1, 3, and 4 (with two duplications in chimera 4), and the third is an intragenic deletion between US34A and TRS1 in chimera 1. A few other minor differences were also noted, as specified in the legend to Figure 1.

Examination of the mutations highlighted in Figure 1A revealed no obvious association between the presence of particular mutations and the efficacy of the chimeras in inducing seroconversion. For example, the fact that chimeras 2 and 3 contain the same mutations except for one impacting UL40 might suggest that an inability to express UL40 renders chimera 3 unable to induce seroconversion. However, the same mutation is present in chimera 4, which is the most immunogenic of the vaccines. Indeed, each of the mutations present in chimera 3 is also present in immunogenic chimeras 2 or 4. Therefore, the ability to induce seroconversion is likely associated with the distribution of parental sequences among the chimeras rather than with specific mutations. For example, sequences from US16 to the right genome terminus are derived from Toledo in chimera 4 and from Towne in the other chimeras. This region contains immune evasion genes (32) and perhaps other elements that may contribute to the relatively enhanced immunogenicity of chimera 4.

Although the phase 1 chimera trial did not include Towne vaccine, comparison to historical data suggested that all four chimeras are attenuated to a level similar to that of the Towne vaccine (13). This indicates that the virulence characteristics associated with Toledo are multifactorial, in that none of the Toledo sequences appeared measurably to enhance virulence when inserted into the Towne genome. Alternatively, it is possible that the RL13 or UL128 mutations present in Toledo passage 8 and the chimeras did not fully pervade the viral population present in the Toledo passage 4 or 5 stocks that proved virulent in humans; that is, that some unmutated virus may have remained at this stage and was responsible for the biological effect. Unfortunately, Toledo passage 8 has not been tested in humans, and samples of earlier passages are no longer available.

The construction and testing of the four chimeric vaccine candidates has provided a rare opportunity to study the genetics of viral pathogenesis in humans. While no specific virulence gene emerged from this limited study, the data suggest that relatively few genetic changes are capable of producing a virus that is highly attenuated and yet capable of replicating in vivo to an extent required to induce both humoral and cellular immune responses. These findings may be valuable for rationally designing live attenuated or replication-defective vaccines that maximize safety while optimizing immunogenicity and efficacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stanley Plotkin for his unwavering support for HCMV vaccine development, Thomas Shenk and Dai Wang for the kind gift of virus BADrUL131, and Greg Duke for review of the manuscript.

Funding This study was funded by the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_12014/3 to AJD) and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) with the generous support of the US Agency for International Development and other donors (a full list of IAVI donors is available at http://www.iavi.org).

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author’s Contributions MAM and SPA conceived the study, MAM and AJD supervised the work and wrote the draft manuscript, NMS, BL, GK, RL, ESM, GWGW, SPA, and MAM prepared and provided the materials and data, and NMS, AJD, and MAM carried out the analyses. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Stratton KR, Durch JS, Lawrence RS, editors. Vaccines for the 21st Century: A Tool for Decisionmaking. The National Academies Press; Washington D.C: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plotkin SA, Furukawa T, Zygraich N, Huygelen C. Infect Immun. 1975;12:521–527. doi: 10.1128/iai.12.3.521-527.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plotkin SA, Smiley ML, Friedman HM, Starr SE, Fleisher GR, Wlodaver C, Dafoe DC, Friedman AD, Grossman RA, Barker CF. Lancet. 1984;1:528–530. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90930-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plotkin SA, Huang ES. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:395–397. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arvin AM, Fast P, Myers M, Plotkin S, Rabinovich R. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:233–239. doi: 10.1086/421999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plotkin SA, Starr SE, Friedman HM, Gönczöl E, Weibel RE. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:860–865. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.5.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quinnan GV, Jr, Delery M, Rook AH, Frederick WR, Epstein JS, Manischewitz JF, Jackson L, Ramsey KM, Mittal K, Plotkin SA, Hilleman MR. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:478–483. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-101-4-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler SP, Starr SE, Plotkin SA, Hempfling SH, Buis J, Manning ML, Best AM. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:26–32. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley AJ, Lurain NS, Ghazal P, Trivedi U, Cunningham C, Baluchova K, Gatherer D, Wilkinson GWG, Dargan DJ, Davison AJ. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:2375–2380. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.013250-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui X, Adler SP, Davison AJ, Smith L, Habib el-SE, McVoy MA. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:428498. doi: 10.1155/2012/428498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cha T-A, Tom E, Kemble GW, Duke GM, Mocarski ES, Spaete RR. J Virol. 1996;70:78–83. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.78-83.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heineman TC, Schleiss M, Bernstein DI, Spaete RR, Yan L, Duke G, Prichard M, Wang Z, Yan Q, Sharp MA, Klein N, Arvin AM, Kemble G. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1350–1360. doi: 10.1086/503365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adler SP, Manganello AM, Lee R, McVoy MA, Nixon DE, Plotkin S, Mocarski E, Cox JH, Fast PE, Nesterenko PA, Murray SE, Hill AB, Kemble G. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1341–1348. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dargan DJ, Douglas E, Cunningham C, Jamieson F, Stanton RJ, Baluchova K, McSharry BP, Tomasec P, Emery VC, Percivalle E, Sarasini A, Gerna G, Wilkinson GWG, Davison AJ. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:1535–1546. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.018994-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanton RJ, Baluchova K, Dargan DJ, Cunningham C, Sheehy O, Seirafian S, McSharry BP, Neale ML, Davies JA, Tomasec P, Davison AJ, Wilkinson GWG. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3191–3208. doi: 10.1172/JCI42955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkinson GWG, Davison AJ, Tomasec P, Fielding CA, Aicheler R, Murrell I, Seirafian S, Wang ECY, Weekes M, Lehner PJ, Wilkie GS, Stanton RJ. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2015;204:273–284. doi: 10.1007/s00430-015-0411-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn G, Revello MG, Patrone M, Percivalle E, Campanini G, Sarasini A, Wagner M, Gallina A, Milanesi G, Koszinowski U, Baldanti F, Gerna G. J Virol. 2004;78:10023–10033. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.10023-10033.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerna G, Percivalle E, Lilleri D, Lozza L, Fornara C, Hahn G, Baldanti F, Revello MG. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:275–284. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D, Shenk T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18153–18158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509201102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adler B, Scrivano L, Ruzcics Z, Rupp B, Sinzger C, Koszinowski U. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:2451–2460. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81921-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryckman BJ, Rainish BL, Chase MC, Borton JA, Nelson JA, Jarvis MA, Johnson DC. J Virol. 2008;82:60–70. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01910-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freed DC, Tang Q, Tang A, Li F, He X, Huang Z, Meng W, Xia L, Finnefrock AC, Durr E, Espeseth AS, Casimiro DR, Zhang N, Shiver JW, Wang D, An Z, Fu TM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E4997–5005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316517110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skaletskaya A, Bartle LM, Chittenden T, McCormick AL, Mocarski ES, Goldmacher VS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:7829–7834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141108798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prichard MN, Penfold ME, Duke GM, Spaete RR, Kemble GW. Rev Med Virol. 2001;11:191–200. doi: 10.1002/rmv.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davison AJ, Dolan A, Akter P, Addison C, Dargan DJ, Alcendor DJ, McGeoch DJ, Hayward GS. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:17–28. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui X, Lee R, Adler SP, McVoy MA. J Virol Methods. 2013;192:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui X, Meza BP, Adler SP, McVoy MA. Vaccine. 2008;26:5760–5766. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lilleri D, Kabanova A, Lanzavecchia A, Gerna G. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:1324–1331. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9739-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ha S, Li F, Troutman MC, Freed DC, Tang A, Loughney JW, Wang D, Wang IM, Vlasak J, Nickle DC, Rustandi RR, Hamm M, DePhillips PA, Zhang N, McLellan JS, Zhu H, Adler SP, McVoy MA, An Z, Fu TM. J Virol. 2017;91:2033–2016. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02033-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saccoccio FM, Sauer AL, Cui X, Armstrong AE, Habib el SE, Johnson DC, Ryckman BJ, Klingelhutz AJ, Adler SP, McVoy MA. Vaccine. 2011;29:2705–2711. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray SE, Nesterenko P, Vanarsdall A, Munks M, Smart S, Veziroglu E, Sagario L, Lee R, Claas FHJ, Doxiadis IIN, McVoy M, Adler SP, Hill AB. J Exp Med. 2017 doi: 10.1084/jem.20161988. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fielding CA, Aicheler R, Stanton RJ, Wang ECY, Han S, Seirafian S, Davies J, McSharry BP, Weekes MP, Antrobus PR, Prod’homme V, Blanchet FP, Sugrue D, Cuff S, Roberts D, Davison AJ, Lehner PJ, Wilkinson GWG, Tomasec P. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004058. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy E, Yu D, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Dickson M, Jarvis MA, Hahn G, Nelson JA, Myers RM, Shenk TE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14976–14981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136652100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunn W, Chou C, Li H, Hai R, Patterson D, Stolc V, Zhu H, Liu F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14223–14228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334032100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brechtel TM, Tyner M, Tandon R. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00901–13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00901-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brondke H, Schmitz B, Doerfler W. Arch Virol. 2007;152:2035–2046. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-1026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang D, Tamburro K, Dittmer D, Cui X, McVoy MA, Hernandez-Alvarado N, Schleiss MR. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00054–13. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00054-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkie GS, Davison AJ, Kerr K, Stidworthy MF, Redrobe S, Steinbach F, Dastjerdi A, Denk D. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6299. doi: 10.1038/srep06299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang D, Shenk T. J Virol. 2005;79:10330–10338. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10330-10338.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]