Abstract

Objective

Normosmic congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (nCHH) is a rare disorder characterised by lack of pubertal development and infertility, due to deficient production, secretion or action of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and, unlike Kallmann syndrome, is associated with a normal sense of smell. Mutations in the GNRHR gene cause autosomal recessive nCHH. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of GNRHR mutations in a group of 40 patients with nCHH.

Design

Cross-sectional study of 40 unrelated patients with nCHH.

Methods

Patients were screened for mutations in the GNRHR gene by DNA sequencing.

Results

GNRHR mutations were identified in five of 40 patients studied. Four patients had biallelic mutations (including a novel frameshift deletion p.Phe313Metfs*3, in two families) in agreement with autosomal recessive inheritance. One patient had a heterozygous GNRHR mutation associated with a heterozygous PROKR2 mutation, thus suggesting a possible role of synergistic heterozygosity in the pathogenesis of the disorder.

Conclusions

This study further expands the spectrum of known genetic defects associated with nCHH. Although GNRHR mutations are usually biallelic and inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, the presence of a monoallelic mutation in a patient should raise the possibility of a digenic/oligogenic cause of nCHH.

Keywords: hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, GNRHR, mutation, genetics

Introduction

Congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (CHH) is characterised by partial or complete lack of pubertal development, secondary to deficient gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-induced gonadotropin secretion (1). Diagnosis is based on the existence of low levels of sex hormones associated with low or inappropriate luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, with no anatomical lesion in the hypothalamic–pituitary tract, and no other pituitary hormone deficiencies. CHH may occur associated with anosmia, a condition referred as Kallmann syndrome, or may occur without associated olfactory abnormalities, referred to as normosmic CHH (nCHH) (1). Genetic studies of patients with CHH have identified monogenic and oligogenic defects in several genes that regulate the embryonic development or migration of GnRH neurons, or the synthesis, secretion or action of GnRH (2).

The gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (GNRHR) gene was one of the first genes to be implicated in nCHH (3, 4). The GNRHR gene is located on chromosome 4q13.2-3 comprises three coding exons and encodes the GnRH receptor (5). The GnRH receptor is expressed mostly at the level of the gonadotrope cells of the pituitary gland, and its activation induces LH and FSH secretion (5). GNRHR mutations explain about 3.5–16% of sporadic cases and up to 40% of familial cases of nCHH (6). Inheritance is autosomal recessive and patients usually have homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations (6).

The aim of this study was to identify and determine the prevalence of GNRHR mutations in a cohort of patients with nCHH.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

The study comprised 40 unrelated Portuguese patients with nCHH (33 men and 7 women), recruited by Portuguese clinical endocrine centres. Inclusion criteria were male and female patients with low serum FSH, LH and sex steroid levels, and failure to enter spontaneous puberty by the age of 18 years or with medically induced puberty below this age and normal sense of smell. Olfactory function was assessed either by olfaction testing or by self-reporting by the patients, depending on the clinical centre. Patients with a history of an acquired cause of hypopituitarism or with abnormal radiological imaging of the hypothalamic–pituitary region were excluded from the study. In mutation-positive patients, additional family members were also studied. The control population consisted of 200 Portuguese unrelated volunteers who were recruited among blood donors. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and the study was approved by the local research ethics committee (Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Beira Interior, Ref: CE-FCS-2012-012).

Genetic studies

Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted from peripheral blood leucocytes using previously described methods (7). Patients were screened for mutations in GNRHR by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the three coding exons and exon–intron boundaries and bi-directional sequencing using CEQ DTCS sequencing kit (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) and an automated capillary DNA sequencer (GenomeLab TM GeXP, Genetic Analysis System, Beckman Coulter). Primer sequences were previously described by Antelli and coworkers (8). The heterozygous frameshift mutation was confirmed by cloning of the PCR products using pGEM-T Easy Vector Systems (Promega Corporation), followed by DNA sequencing of each allele. Genomic sequence variants identified in patients were searched in population variant databases (Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) database) (9) to assess their frequency in the general population. Computational functional prediction analysis (10) was performed to evaluate the impact of the sequence variants on protein function. Unreported variants were excluded in a panel of 200 healthy Portuguese volunteers (400 alleles). Mutation nomenclature followed standard guidelines (11) and was based on the cDNA reference sequence for the GNRHR gene (GenBank accession NM_000406.2). In the patient with a monoallelic mutation in exon 1 of GNRHR, a ~4.5 kb PCR fragment encompassing exons 2 and 3 was analysed to exclude large deletions of either exon. In addition, this patient was screened for digenic/oligogenic mutations by sequencing additional genes related to the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis (KAL1, FGFR1, GNRH1, FGF8, PROK2, PROKR2, KISS1R, CHD7, TAC3 and TACR3) (all primer sequences and PCR conditions are available upon request).

Results

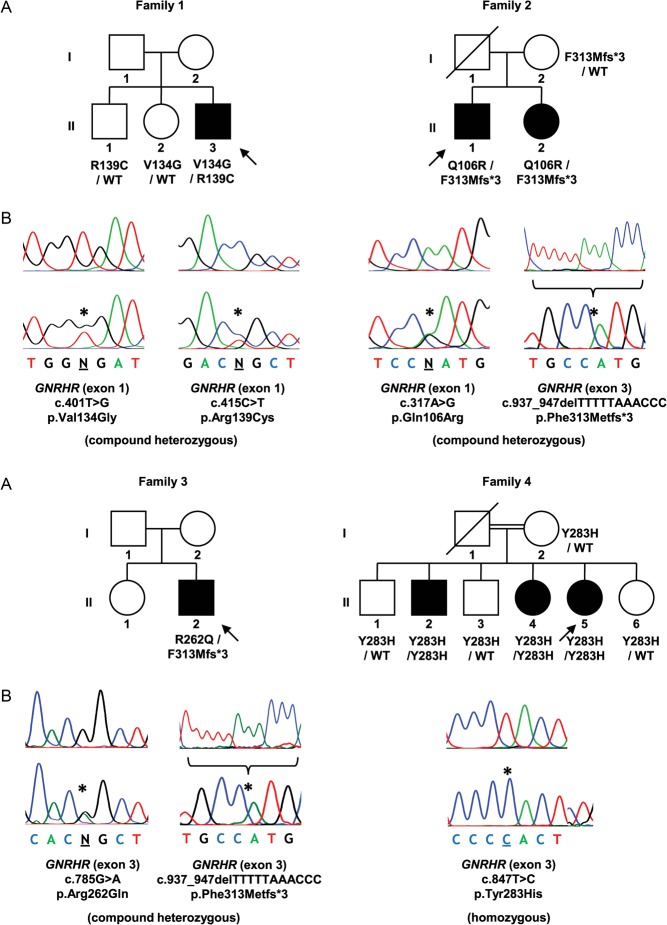

Sequence analysis of the entire coding region of GNRHR, including exon–intron boundary regions, revealed mutations in five (12.5%) patients (Figs 1 and 2). These consisted of a compound heterozygous missense mutation (c.[401T > G];[415C > T]) (p.[Val134Gly];[Arg139Cys]), a compound heterozygous missense/frameshift mutation (c.[317A>G];[937_947del]) (p.[Gln106Arg];[Phe313Metfs*3]), a compound heterozygous missense/frameshift mutation (c.[785G > A];[937_947del]) (p.[Arg262Gln];[Phe313Metfs*3]), a homozygous missense mutation (c.[847T > C];[847T > C]) (p.[Tyr283His];[Tyr283His]) and a heterozygous missense mutation (c.[401T > G];[=]) (p.Val134Gly). Three of these patients were sporadic cases and two had additional affected siblings that were also tested and shown to share the same mutations. The clinical characteristics of patients with identified GNRHR mutations are summarised in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Mutations identified in patients with nCHH. (A) Pedigrees of affected individuals. Arrows represent index cases, filled symbols represent affected individuals, open symbols represent unaffected individuals, squares denote men, circles denote women, oblique lines through symbols represent deceased individuals and double line represents consanguineous marriage. Genotypes for tested family members, when available, are presented below each individual. WT, wild-type allele. (B) DNA sequence analysis of normal individuals (above) and patients (below). The positions of the mutations are indicated by asterisks. In the case of the deletion (p.Phe313Metfs*3) (family 2 and 3), only the cloned mutated allele is represented (below) with the deleted sequence (above).

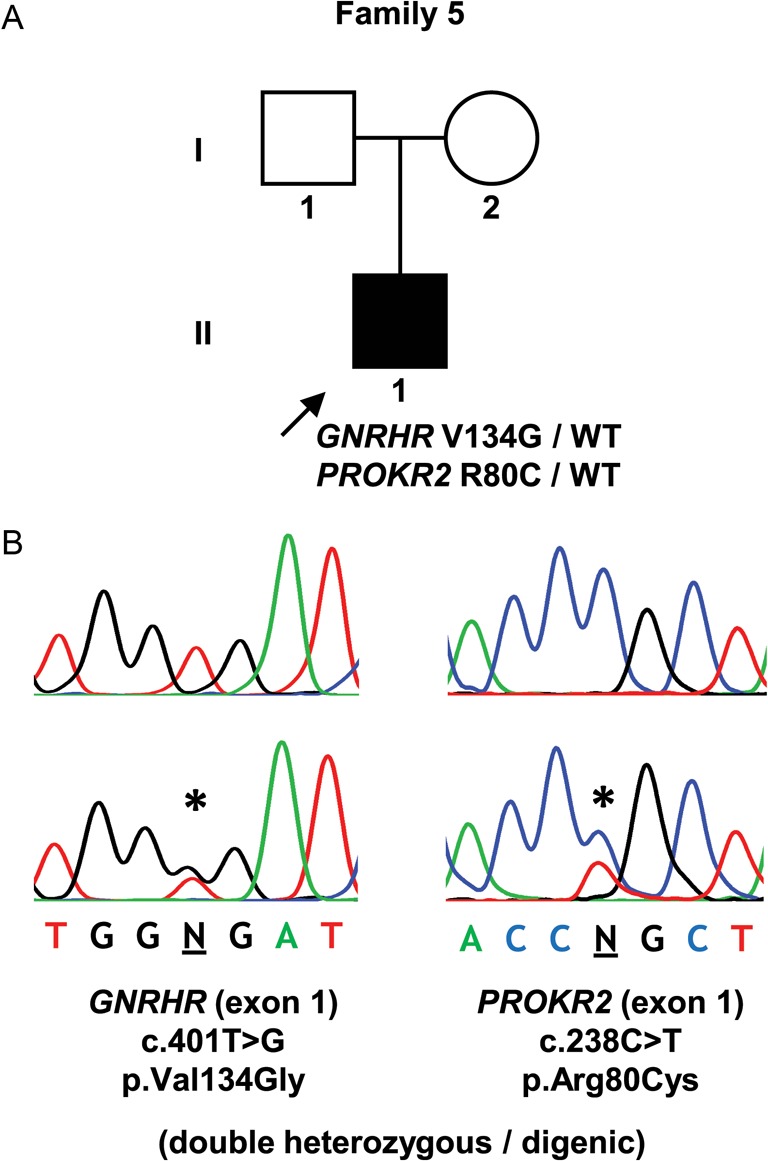

Figure 2.

Digenic mutation identified in a patient with nCHH. (A) Pedigree of the affected individual. (B) DNA sequence analysis of a normal individual (above) and the patient (below). Symbols as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with GNRHR mutations.

| Family | Member (a) | Sex | Age of diagnosis (years) | Clinical presentation | Olfaction (b) | Associated features | Basal hormone levels (laboratory normal reference range) | Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | II-3 | M | 18.5 | Delayed puberty. Micropenis. Tanner stage 3. Testicular volume 3 mL | Normal | Surgery for right-sided cryptorchidism at age 1.5 years | FSH 1.2 IU/mL (1.0–8.0); LH 0.5 IU/mL (0.7–7.2); total testosterone 0.20 ng/mL (2.60–10.00) | GNRHR p.[Val134Gly];[Arg139Cys] (compound heterozygous) |

| 2 | II-1 | M | 22 | Delayed puberty. Tanner stage 1. Testicular volume 5 mL | Normal | FSH 2.4 IU/mL (2.5–10.2); LH <0.1 IU/mL (1.9–2.5); total testosterone 0.33 ng/mL (2.60–10.00) | GNRHR p.[Gln106Arg];[Phe313Metfs*3] (compound heterozygous) | |

| II-2 | F | 18 | Primary amenorrhea | Normal | FSH 2.2 IU/mL (2.5–10.2); LH 0.9 IU/mL (1.9–2.5); estradiol 15 pg/mL (11–69) | GNRHR p.[Gln106Arg];[Phe313Metfs*3] (compound heterozygous) | ||

| 3 | II-2 | M | 51 | Delayed puberty. Tanner stage 1. Testicular volume 5 mL | Normal | Low bone mineral density (lumbar spine T-score −2.3; femoral neck T-score −2.8) | FSH 1.1 IU/mL (1.0–8.0); LH 0.4 IU/mL (0.7–7.2); total testosterone 0.40 ng/mL (2.70–11.00) | GNRHR p.[Arg262Gln];[Phe313Metfs*3] (compound heterozygous) |

| 4 | II-2 | M | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | GNRHR p.[Tyr283His];[Tyr283His] (homozygous) | |

| II-4 | F | n/a | Primary amenorrhea | Normal | FSH 0.4 IU/mL (1.5–33.4); LH <0.07 IU/mL (1.7–15.0); estradiol <11.8 pg/mL (19.5–356.7) | GNRHR p.[Tyr283His];[Tyr283His] (homozygous) | ||

| II-5 | F | 39 | Primary amenorrhea | Normal | Low bone mineral density (lumbar spine T-score −3.2; femoral neck T-score −1.0). Hypercholesterolemia. Secondary sex characteristics had developed due to oral contraceptive use in adolescence | FSH 0.7 IU/mL (4.0–13.0); LH 0.1 IU/mL (1.7–15.0); estradiol <10 pg/mL (20–150) | GNRHR p.[Tyr283His];[Tyr283His] (homozygous) | |

| 5 | II-1 | M | 15 | Delayed puberty. Tanner stage 1. Testicular volume <5 mL | Normal | Surgery for left-sided cryptorchidism at age 10 years | FSH 0.5 IU/mL (1.4–18.0); LH 0.7 IU/mL (1.5–9.3); total testosterone 0.09 ng/mL (2.20–8.00) | GNRHR p.Val134Gly (heterozygous) + PROKR2 p.Arg80Cys (heterozygous) |

In the patient with the monoallelic mutation in exon 1 (p.Val134Gly), additional studies were carried out to search for further genetic defects. A PCR amplicon containing GNRHR exons 2 and 3 was partially sequenced and revealed heterozygosity for an intron 2 polymorphism (rs373270328), thereby indicating the presence of two copies of each exon and excluding the possibility of exon deletion as the second mutation in this patient. The screening of other genes related to the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis, in this patient, revealed an additional heterozygous missense mutation (c.[238C > T];[=]) (p.Arg80Cys) in the PROKR2 gene.

The GNRHR frameshift mutation was identified in two different families and has not been reported before. It consists of an 11 base-pair deletion (c.937_947delTTTTTAAACCC), and if translated, would be expected to result in a truncated protein due to a premature termination codon (p.Phe313Metfs*3). This deletion was not found in any of the population variant databases and was excluded in a panel of 200 normal Portuguese controls (400 alleles), on the basis of the different size of the PCR fragments. The remaining missense variants have all been identified as mutations in previous studies and were predicted to have a damaging effect on the encoded protein, by SIFT and PolyPhen-2 analyses (10). Furthermore, these missense mutations were either unreported in the ExAC population database (p.Arg139Cys, and p.Tyr283His) or reported at rare frequencies (p.Gln106Arg, at 0.2%; p.Val134Gly, at 0.0008%; p.Arg262Gln at 0.2%; and PROKR2 p.Arg80Cys at 0.0008%).

Discussion

The overall prevalence of GNRHR mutations in this cohort was 12.5% (five out of 40 patients with nCHH), which is consistent with results presented in other studies (6). Four patients had biallelic mutations (including two patients with a novel frameshift deletion) and one patient had a digenic (GNRHR/PROKR2) heterozygous mutation.

The GNRHR missense mutations identified in this study have been previously reported in other nCHH patients, namely p.Gln106Arg (3), p.Val134Gly (12), p.Arg139Cys (13), p.Arg262Gln (3) and p.Tyr283His (14). In vitro functional studies have demonstrated that these mutated receptors result in either reduced ligand affinity, reduced signal transduction or abolished plasma membrane expression (3, 12, 13). The 11 base-pair deletion (c.937_947delTTTTTAAACCC) has never been reported before and was identified in two different families from the same geographical region, suggesting a possible inheritance from a common ancestor. This deletion is likely to be highly deleterious due to a frameshift effect and to the formation of a premature stop codon that may lead to the production of a truncated protein (p.Phe313Metfs*3) or to nonsense-mediated messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) decay (15), although the latter is less likely due to the location of the mutation in the last exon.

Four patients had biallelic mutations (either homozygous or compound heterozygous), which is in agreement with the typical autosomal recessive inheritance of GNRHR. However, one patient had a GNRHR mutation on one of the alleles (p.Val134Gly), but no mutation on the other allele. Other monoallelic mutations of GNRHR have been reported in patients with CHH and have challenged the traditional view of GNRHR as a recessive gene (16). It has been suggested that such patients with monoallelic mutations may have additional mutations in other genes that act synergistically to produce the phenotype (16). To explore this possibility, we screened this patient for mutations in other commonly implicated genes in CHH and identified an additional heterozygous missense mutation (p.Arg80Cys) in the PROKR2 gene. Interestingly, the same heterozygous PROKR2 mutation has been identified in a Brazilian patient with Kallmann syndrome (17) and has been shown to exert a dominant-negative effect under certain in vitro conditions (18). However, this mutation was also found in two asymptomatic first-degree relatives, leading the authors to conclude that this mutation, by itself, was insufficient to cause the disorder, but that it might contribute to the disease phenotype in association with other factors, such as unidentified mutations in additional genes or epigenetic and environmental effects (17). Indeed, our finding of a digenic (GNRHR/PROKR2) heterozygous mutation supports this possibility and indicates the need to consider a digenic/oligogenic cause of CHH in patients with GNRHR monoallelic mutations.

Digenic and oligogenic inheritance has been identified in several cases of CHH. A study by Sykiotis et al. (19) found that 2.5% of patients with CHH harboured mutations in two or more genes. However, so far, there have been only four reported CHH patients with digenic mutations involving a single heterozygous GNRHR mutation and a mutation in another gene, namely in FGFR1 (16, 19), WDR11 (20) and PROKR2 (p.Val331Met) (16). Therefore, our patient represents a rare example of digenism involving GNRHR and supports the hypothesis that heterozygous mutations, in genes that normally cause autosomal recessive disease, may affect the same regulatory pathways and result in disease by synergistic heterozygosity. A similar mechanism of synergistic heterozygosity has been proposed for other disorders such as inborn errors of metabolism (21). The involvement of digenism as a cause of CHH suggests that there are multiple layers of redundancy in the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) control of reproduction and that, at least in the case of less severe mutations, multiple hits in the HPG axis may be required to result in CHH (22).

Our findings of a monoallelic mutation in GNRHR should be viewed with caution as we did not exclude the possibility of a second mutation in non-coding sequences, such as deep intronic or regulatory regions. However, such mutations have not yet been reported in any patient. Although we searched for oligogenicity by sequencing the most commonly affected CHH genes, other rarer loci were not analysed, and it remains to be determined if a more comprehensive genetic analysis (e.g. through whole-exome sequencing) would uncover additional contributing variants. Finally, family members of affected individuals were not always available for analysis and would have been useful for the interpretation of the genetic results.

In conclusion, our study identified a previously unreported mutation of the GNRHR gene, thereby expanding the spectrum of mutations associated with nCHH. In addition, we identified a case of a digenic (GNRHR/PROKR2) heterozygous mutation, suggesting that synergistic heterozygosity within the same regulatory pathway may also play a role in the pathogenesis of the disorder.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This work was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (PTDC/SAU-GMG/098419/2008). C I G is the recipient of a PhD fellowship grant (SFRH/BD/76420/2011).

Author contribution statement

C I G and M C L conceived and designed the study. C I G performed the genetic studies of the patients. J M A, M B, L B, N V and D C collected samples and acquired clinical data of the patients with mutations. C I G and M C L drafted the article and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the following clinicians who contributed with patient samples and data: Ana Saavedra (Porto), Ana Varela (Porto), António Garrão (Lisboa), Bernardo Pereira (Almada), Carla Baptista (Coimbra), Carla Meireles (Guimarães), Carolina Moreno (Coimbra), Catarina Limbert (Lisboa) Cíntia Correia (Porto), Cláudia Nogueira (Porto), Duarte Pignatelli (Porto), Eduardo Vinha (Porto), Fernando Fonseca (Lisboa), Filipe Cunha (Porto), Francisco Carrilho (Coimbra), Luísa Cortez (Lisboa), Maria João Oliveira (Porto), Mariana Martinho (Penafiel), Miguel Melo (Coimbra), Patrícia Oliveira (Coimbra), Paula Freitas (Porto), Raquel Martins (Porto), Selma Souto (Porto), Sofia Martins (Braga), Susana Gama (Famalicão) and Teresa Martins (Coimbra).

References

- 1.Boehm U, Bouloux PM, Dattani MT, de Roux N, Dode C, Dunkel L, Dwyer AA, Giacobini P, Hardelin JP, Juul A, et al. Expert consensus document: European Consensus Statement on congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism – pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2015. 11 547–564. ( 10.1038/nrendo.2015.112) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SH. Congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and kallmann syndrome: past, present, and future. Endocrinology and Metabolism 2015. 30 456–466. ( 10.3803/EnM.2015.30.4.456) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Roux N, Young J, Misrahi M, Genet R, Chanson P, Schaison G, Milgrom E. A family with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and mutations in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. New England Journal of Medicine 1997. 337 1597–1602. ( 10.1056/NEJM199711273372205) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Layman LC, Cohen DP, Jin M, Xie J, Li Z, Reindollar RH, Bolbolan S, Bick DP, Sherins RR, Duck LW, et al. Mutations in gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene cause hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Nature Genetics 1998. 18 14–15. ( 10.1038/ng0198-14) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chevrier L, Guimiot F, de Roux N. GnRH receptor mutations in isolated gonadotropic deficiency. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2011. 346 21–28. ( 10.1016/j.mce.2011.04.018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianco SD, Kaiser UB. The genetic and molecular basis of idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2009. 5 569–576. ( 10.1038/nrendo.2009.177) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemos MC, Regateiro FJ. N-acetyltransferase genotypes in the Portuguese population. Pharmacogenetics 1998. 8 561–564. ( 10.1097/00008571-199812000-00013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antelli A, Baldazzi L, Balsamo A, Pirazzoli P, Nicoletti A, Gennari M, Cicognani A. Two novel GnRHR gene mutations in two siblings with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. European Journal of Endocrinology 2006. 155 201–205. ( 10.1530/eje.1.02198) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ExAC. Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC). Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. (available at: http://exac.broadinstitute.org) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Min L, Nie M, Zhang A, Wen J, Noel SD, Lee V, Carroll RS, Kaiser UB. Computational analysis of missense variants of G protein-coupled receptors involved in the neuroendocrine regulation of reproduction. Neuroendocrinology 2016. 103 230–239. ( 10.1159/000435884) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR, Hart RK, Greenblatt MS, McGowan-Jordan J, Roux AF, Smith T, Antonarakis SE, Taschner PE. HGVS recommendations for the description of sequence variants: 2016 update. Human Mutation 2016. 37 564–569. ( 10.1002/humu.22981) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beneduzzi D, Trarbach EB, Min L, Jorge AA, Garmes HM, Renk AC, Fichna M, Fichna P, Arantes KA, Costa EM, et al. Role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor mutations in patients with a wide spectrum of pubertal delay. Fertility and Sterility 2014. 102 838.e832–846.e832. ( 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.044) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Topaloglu AK, Lu ZL, Farooqi IS, Mungan NO, Yuksel B, O'Rahilly S, Millar RP. Molecular genetic analysis of normosmic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in a Turkish population: identification and detailed functional characterization of a novel mutation in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Neuroendocrinology 2006. 84 301–308. ( 10.1159/000098147) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beneduzzi D, Trarbach EB, Latronico AC, Mendonca BB, Silveira LF. Novel mutation in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (GNRHR) gene in a patient with normosmic isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia and Metabologia 2012. 56 540–544. ( 10.1590/s0004-27302012000800013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker KE, Parker R. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: terminating erroneous gene expression. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 2004. 16 293–299. ( 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.03.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gianetti E, Hall JE, Au MG, Kaiser UB, Quinton R, Stewart JA, Metzger DL, Pitteloud N, Mericq V, Merino PM, et al. When genetic load does not correlate with phenotypic spectrum: lessons from the GnRH receptor (GNRHR). Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2012. 97 E1798–E1807. ( 10.1210/jc.2012-1264) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abreu AP, Trarbach EB, de Castro M, Frade Costa EM, Versiani B, Matias Baptista MT, Garmes HM, Mendonca BB, Latronico AC. Loss-of-function mutations in the genes encoding prokineticin-2 or prokineticin receptor-2 cause autosomal recessive Kallmann syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2008. 93 4113–4118. ( 10.1210/jc.2008-0958) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abreu AP, Noel SD, Xu S, Carroll RS, Latronico AC, Kaiser UB. Evidence of the importance of the first intracellular loop of prokineticin receptor 2 in receptor function. Molecular Endocrinology 2012. 26 1417–1427. ( 10.1210/me.2012-1102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sykiotis GP, Plummer L, Hughes VA, Au M, Durrani S, Nayak-Young S, Dwyer AA, Quinton R, Hall JE, Gusella JF, et al. Oligogenic basis of isolated gonadotropin-releasing hormone deficiency. PNAS 2010. 107 15140–15144. ( 10.1073/pnas.1009622107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quaynor SD, Kim HG, Cappello EM, Williams T, Chorich LP, Bick DP, Sherins RJ, Layman LC. The prevalence of digenic mutations in patients with normosmic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and Kallmann syndrome. Fertility and Sterility 2011. 96 1424.e1426–1430.e1426. ( 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.09.046) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vockley J. Metabolism as a complex genetic trait, a systems biology approach: implications for inborn errors of metabolism and clinical diseases. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 2008. 31 619–629. ( 10.1007/s10545-008-1005-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herbison AE. Control of puberty onset and fertility by gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2016. 12 452–466. ( 10.1038/nrendo.2016.70) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a