ABSTRACT

Disulfide bonds are critical to the stability and function of many bacterial proteins. In the periplasm of Escherichia coli, intramolecular disulfide bond formation is catalyzed by the two-component disulfide bond forming (DSB) system. Inactivation of the DSB pathway has been shown to lead to a number of pleotropic effects, although cells remain viable under standard laboratory conditions. However, we show here that dsb strains of E. coli reversibly filament under aerobic conditions and fail to grow anaerobically unless a strong oxidant is provided in the growth medium. These findings demonstrate that the background disulfide bond formation necessary to maintain the viability of dsb strains is oxygen dependent. LptD, a key component of the lipopolysaccharide transport system, fails to fold properly in dsb strains exposed to anaerobic conditions, suggesting that these mutants may have defects in outer membrane assembly. We also show that anaerobic growth of dsb mutants can be restored by suppressor mutations in the disulfide bond isomerization system. Overall, our results underscore the importance of proper disulfide bond formation to pathways critical to E. coli viability under conditions where oxygen is limited.

IMPORTANCE While the disulfide bond formation (DSB) system of E. coli has been studied for decades and has been shown to play an important role in the proper folding of many proteins, including some associated with virulence, it was considered dispensable for growth under most laboratory conditions. This work represents the first attempt to study the effects of the DSB system under strictly anaerobic conditions, simulating the environment encountered by pathogenic E. coli strains in the human intestinal tract. By demonstrating that the DSB system is essential for growth under such conditions, this work suggests that compounds inhibiting Dsb enzymes might act not only as antivirulents but also as true antibiotics.

KEYWORDS: disulfide bonds, anaerobiosis, LptD, dsbC, dsbA, dsbB, disulfide bond, lptD

INTRODUCTION

Intramolecular disulfide bonds are critical to the structural integrity of many proteins found in the bacterial cell envelope. Among these disulfide-stabilized proteins are phosphatases (1), toxins (2), components of the flagellar motor (3), and enzymes involved in the assembly of the outer membrane (4). While it was long thought that disulfide bonds formed spontaneously in aerobic environments due to background oxidation (5), it has been suggested that this spontaneous rate of disulfide formation is too low for many physiological processes. Enzymatic systems dedicated to catalyzing disulfide bond formation were identified first in prokaryotes and subsequently in eukaryotes (6, 7). Many Gram-negative bacteria, like Escherichia coli, utilize the disulfide bond forming (DSB) pathway for introducing disulfides into newly secreted proteins. In this pathway, two electrons are passed from substrate proteins to the periplasmic thioredoxin-like protein DsbA via a critical cysteine residue. This process gives rise to a disulfide bond in the substrate protein while simultaneously reducing DsbA, which is quickly recycled to its active oxidized form by the membrane-bound DsbB. DsbB in turn is reoxidized by quinones embedded in the inner membrane (8). In the absence of either Dsb protein, E. coli displays dramatic reductions in motility (3), alkaline phosphatase activity, and virulence (9), and these phenotypes have been shown to be due to the lack of a disulfide bond in critical proteins. This clearly demonstrates that disulfide bonds are essential to the functionality of many E. coli proteins and that the DSB system is key to the formation of these bonds. Despite the importance of this system, however, dsb mutants of E. coli display no overt growth defects when cultured under aerobic conditions. This is especially confounding when it is considered that at least two essential proteins associated with the cell wall require disulfide bonds for activity (LptD [4] and FtsN [10]). How then are dsb mutants viable?

One potential explanation for the viability of dsb mutants is the presence of a backup enzyme(s) capable of catalyzing disulfide bond formation. While attempts to identify such an enzyme have given greater insights into the pathways mediating disulfide bond formation and isomerization (11, 12), no enzyme has been found to date that adequately accounts for the amount of background oxidation displayed by dsb strains. An alternative hypothesis is that the spontaneous rate of disulfide bond formation in an aerobic environment is in fact sufficient for the proper folding of proteins essential to viability under standard laboratory conditions. If this hypothesis were true, dsb strains would fail to grow under anaerobic conditions. We therefore sought to test what effects anaerobiosis might have on the viability and morphology of strains missing different components of the DSB pathway.

RESULTS

The DSB pathway is essential under anaerobic conditions.

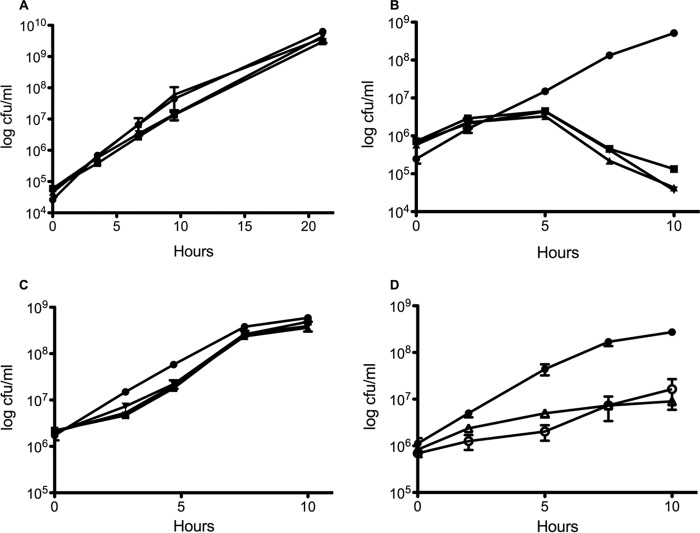

Because we reasoned that the growth of dsb mutants is facilitated by oxygen-dependent chemical oxidation of essential proteins, we hypothesized that dsb mutants should fail to grow under anaerobic conditions. To test this, we grew such mutants aerobically and then diluted them into anaerobic growth medium. While these strains showed no significant difference in aerobic growth compared to the wild type (Fig. 1A), they displayed a severe growth defect anaerobically (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

The DSB pathway is essential under anaerobic conditions. Log-phase aerobic cultures were diluted into M63glu and grown at 37°C aerobically (A), M63glu with 40 mM nitrate and grown at 37°C in an anaerobic chamber (B), or M63glu with 40 mM nitrate and 100 μM cystine and grown at 37°C in an anaerobic chamber (C). Samples were taken over time, serially diluted in LB, and plated to LB aerobically. After overnight incubation at 37°C, CFU were enumerated. ●, WT; ■, ΔdsbA mutant; ▲, ΔdsbB mutant; ▼, ΔdsbAB mutant. (D) Mutants impaired in quinone production were also assayed for growth in M63glu with nitrate anaerobically. ●, WT; △, ΔmenA ubi; ○, ΔmenA ubi plus 100 μM cystine. Growth curves were performed in triplicate and are plotted ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

While the growth defect of dsb mutants was most likely due to the loss of disulfide bonds in some essential periplasmic proteins, it was possible that the loss of these gene products (especially the integral membrane protein DsbB) has pleotropic effects on the cells. To confirm that the lack of disulfide bonds was what was preventing anaerobic growth, we supplemented the anaerobic growth medium with cystine, a strong oxidant capable of restoring disulfide bond formation in dsb mutants (13). As shown in Fig. 1C, cystine supported growth of the dsb mutants anaerobically.

Because the penultimate step in the DSB pathway is the delivery of electrons from DsbB to quinones, strains impaired in quinone production should also display an anaerobic growth defect. Figure 1D shows that a ΔmenA ubi strain is indeed impaired in anaerobic growth compared to the wild type, although not to the extent of the dsb strains. Cystine supplementation did not reverse the growth defect, suggesting that there may be pleiotropic effects associated with such mutations.

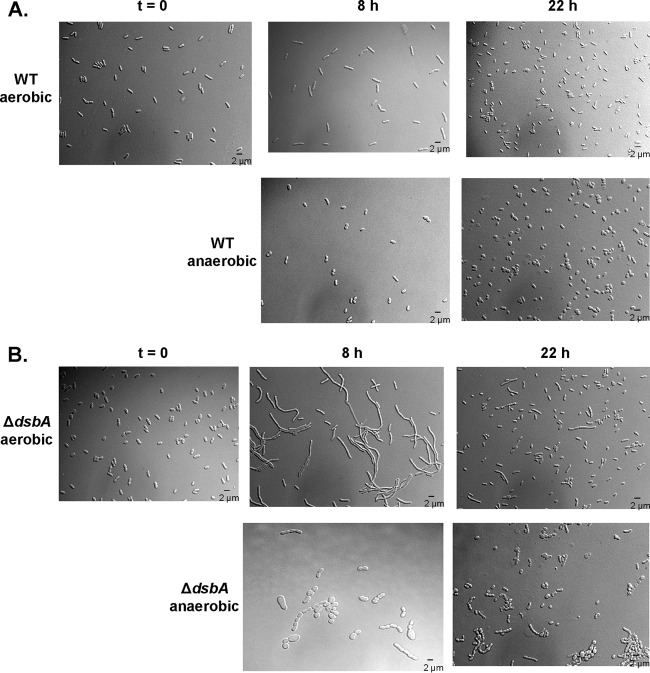

Mutants lacking a functional DSB system display gross morphological differences.

To gain insights into the molecular nature of the anaerobic growth defect, we visualized wild-type and dsb mutant strains microscopically after aerobic growth or after exposing cultures to anaerobic conditions for several hours (Fig. 2). While wild-type cells displayed the short-rod morphology typically associated with E. coli, ΔdsbA mutant cells exposed to anaerobic conditions appeared to form chains and filaments, with some showing bulging membranes and others appearing as small spheres. Surprisingly, the ΔdsbA mutant strain also showed signs of filamentation aerobically at the 8-h time point, suggesting that any background oxidation that was occurring was significantly less efficient than DSB-catalyzed disulfide bond formation. These phenotypes were also observed for ΔdsbB and ΔdsbAB mutant strains (data not shown). After 22 h of growth, however, ΔdsbA mutant cells displayed a morphology much more closely resembling wild-type cells, suggesting that filamentation could be resolved in the presence of oxygen.

FIG 2.

dsb mutants display gross morphological changes. Wild-type (HK295) (A) and ΔdsbA mutant (HK317) (B) strains were grown aerobically in M63glu at 37°C to log phase and then diluted 1:1,000 into M63glu aerobically or M63glu with 40 mM nitrate anaerobically (t = 0). Samples were taken over time, and cells were concentrated via centrifugation. Aliquots were applied to agarose pads affixed to microscope slides and visualized with DIC microscopy.

Anaerobic growth defect of strains with mutations in the disulfide bond-generating pathway can be suppressed by mutations in the disulfide isomerization pathway.

The above-mentioned results suggested that dsb strains fail to grow anaerobically because an essential disulfide bond(s) fails to form in an essential protein(s). To identify which misfolded protein might be preventing growth, we hoped to isolate spontaneous mutants capable of bypassing the impaired pathway by selecting for anaerobic growth of a ΔdsbA or ΔdsbB mutant strain. We performed these selections in liquid and solid media by incubating these mutant strains under anaerobic conditions for up to 1 week. Several suppressor mutants were isolated in this manner, and all encoded mutations in either dsbC or trxB (Table 1), key components of the disulfide bond isomerization pathway. Similar mutations have been isolated previously (12, 14), and while such mutations did not give insight into which DsbA substrate might be preventing anaerobic growth, they further expanded our understanding of how the disulfide bond isomerization pathway can be altered to promote disulfide bond generation. Attempts to isolate spontaneous mutants that would suppress the anaerobic growth defect of a ΔdsbA ΔdsbC mutant strain were unsuccessful.

TABLE 1.

Spontaneous suppressors of dsb mutants can be isolated anaerobicallya

| Background | Suppressor mutation | Medium |

|---|---|---|

| ΔdsbA | dsbC Gly69Arg | Liquid |

| ΔdsbA | dsbC Ala42Glu | Solid |

| ΔdsbA | trxB ΔThr48 | Solid |

| ΔdsbA | trxB frameshift nt 582/583 | Solid |

| ΔdsbB | trxB Δnt819 | Solid |

| ΔdsbB | trxB Gly239Asp | Solid |

| ΔdsbB | trxB Pro16Leu | Solid |

| ΔdsbB | trxB Gly55Cys | Solid |

Strain HK317 (ΔdsbA mutant) or HK320 (ΔdsbB mutant) was grown aerobically in M63glu and then inoculated into M63glu with 40 mM nitrate anaerobically or spread anaerobically on plates containing the same medium. DNA was prepared from suppressor mutants that arose and sequenced to determine the identity of the mutation. nt, nucleotides.

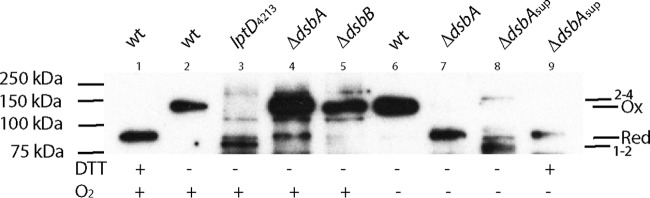

LptD accumulates in the reduced inactive form in a ΔdsbA mutant strain exposed to anaerobic conditions.

Because the spontaneous suppressor mutations did not identify the DsbA substrate crucial to anaerobic growth, we sought to investigate one candidate substrate more directly. LptD is an outer membrane protein critical to the proper export of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to the outer membrane. LptD contains 4 cysteine residues, and in its fully mature folded form, these cysteines are engaged in two nonconsecutive disulfide bonds (1–3 and 2–4) that form in a sequential process. Upon secretion of LptD into the periplasm, DsbA normally engages it and catalyzes a disulfide bond between the first cysteine (Cys31) and the second cysteine (Cys173) to make the 1–2 disulfide bond. The association of LptD with its partner, LptE (4), and/or the isomerase activity of DsbC (15), rearranges this disulfide such that Cys173 now becomes bonded to the fourth cysteine (Cys725) to make the 2–4 disulfide bond. At this point, DsbA reengages LptD to catalyze a second disulfide bond between the remaining cysteines (Cys31 and Cys724), resulting in the 1–3 disulfide bond (16). Mutational analysis has shown that in order for LptD to transport LPS to the outer membrane, at least one of the disulfide bonds (1–3 or 2–4) must be present (4). We therefore reasoned that a dsb strain exposed to anaerobic conditions would not be able to assemble a properly folded functional LptD.

To test this, we grew wild-type and ΔdsbA and ΔdsbB mutant strains aerobically and isolated the outer membrane fractions for use in immunoblot detection of LptD. Because the folding intermediates of LptD can be readily detected due to differences in mobility through an SDS gel, we were able to investigate the effects of these deletions on the folding state of LptD.

Previous studies found that a ΔdsbA mutant strain grown aerobically in minimal medium accumulated LptD in the fully reduced form, as well as in the 2–4-disulfide-bonded form (16). While we find both LptD forms in the ΔdsbA mutant strain grown aerobically, we find that the major form of LptD present in this strain is in the fully oxidized (1–3 and 2–4 disulfides) state (Fig. 3, lane 4). The presence of this fully oxidized state is most likely due to growing the cells for more generations before preparing samples, thus allowing for greater background oxidation. We could not readily detect any of the reduced form in a ΔdsbB mutant strain, as LptD was found to be mostly in the fully oxidized state, with a small amount present in the 2–4 configuration (Fig. 3, lane 5). To confirm one of these forms, we compared the oxidation states of LptD to those displayed by a strain expressing the LptD4213 allele, which harbors a deletion of amino acids 330 to 352 and has been shown to accumulate LptD in the 1–2 form (16) (Fig. 3, lane 3). Aerobically grown cultures of wild-type and ΔdsbA mutant strains were also diluted into minimal medium and exposed to anaerobic conditions. As Fig. 1 shows, the ΔdsbA mutant strain grows for a few hours before growth ceases. We reasoned that any disulfide-bonded LptD would be diluted out during these few doublings, and newly secreted LptD would accumulate in the reduced form. While the wild-type strain contained only fully oxidized LptD (Fig. 3, lane 6), the ΔdsbA mutant strain contained only the reduced form of LptD (Fig. 3, lane 7).

FIG 3.

LptD accumulates in the reduced inactive form in a ΔdsbA mutant strain exposed to anaerobic conditions. Strains were grown aerobically to log phase, and cells were collected after using culture to inoculate anaerobic growth medium. Cells were collected from anaerobic cultures after several hours of exposure, and outer membranes were isolated from both aerobic and anaerobic samples. These membranes were run on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a membrane that was immunoblotted with an anti-LptD antibody. Dithiothreitol (DTT) was added to a wild-type sample to distinguish oxidized versus reduced LptD. The ΔdsbAsup mutant encodes the dsbC Gly69Arg mutation. 1–2, disulfide bond between the first two cysteines of LptD; 2–4, disulfide bond between the second and fourth cysteines of LptD; Ox, oxidized (1–3 and 2–4 disulfides present); Red, reduced (no disulfide bonds).

The fact that mutations in the disulfide bond isomerization pathway can suppress the anaerobic growth defect of dsb strains suggested that at least some fraction of LptD must fold properly in these mutants. We therefore sought to determine the oxidation state of LptD in one ΔdsbA mutant suppressor (dsbC Gly69Arg) grown under anaerobic conditions. While some of the LptD in this strain appeared to accumulate in the reduced state like a ΔdsbA mutant strain, there was also the appearance of the 1–2 disulfide intermediate, as well as the 2–4 disulfide-bonded form (Fig. 3, lane 8). This suggests that the mutant DsbC was capable of supporting sufficient LptD folding.

DISCUSSION

Disulfide bonds are critical to the stability and functionality of at least two essential proteins in the periplasm of E. coli. Since formation of these bonds is normally catalyzed by the DSB pathway, the fact that dsb strains are viable has been confounding. The growth of such strains has been attributed to “background oxidation,” but the source of this oxidation has not yet been elucidated. One potential explanation has been that disulfides form spontaneously in an aerobic environment, but the rate at which such reactions would occur has been suggested to be physiologically insufficient. The results presented here suggest that an aerobic environment provides enough oxidizing power to support the growth of E. coli, even though the level of disulfide bond formation for specific proteins varies. In the absence of oxygen, strains lacking a functional DSB pathway failed to grow in liquid medium unless an alternative oxidant (cystine) was added to the culture medium. We found, however, that solid agar-based media were not selective against dsb strains. Agar has been shown to contain many impurities as a result of its manufacturing process, and different brands and types of agar can have significant effects on growth (17). One of the more abundant impurities is sulfur, and trace amounts of zinc, iron, and cadmium can also be found (17). All of these could potentially act as oxidants capable of catalyzing disulfide bond formation in dsb strains, thus offering an explanation for the lack of selectivity of agar-solidified media under anaerobic conditions. Noble agar, a more highly purified solidifying agent, was also not selective. However, we consistently found that M63 medium containing 0.2% glucose (M63glu) solidified with 1% agarose did not support the anaerobic growth of strains lacking a functional DSB pathway, even though the bacteria showed robust growth on the same medium under aerobic conditions.

Strains lacking the major quinones displayed an anaerobic growth defect that was less severe than those lacking dsbA or dsbB. This may be due to the fact that DsbB can oxidize some fraction of DsbA molecules even in the absence of quinones by an unknown mechanism (18, 19). The fact that supplementation of the anaerobic growth medium with cystine and uracil (to bypass a known deficiency in dihydroorotate dehydrogenase [20]) did not completely restore growth to the quinone-less mutant suggests that other pathways require quinones for maximal function.

Surprisingly, even though dsb strains showed no significant reduction in CFU under aerobic conditions, they appeared to filament during log phase. Clearly, an aerobic environment was not as efficient as the DSB pathway in introducing disulfide bonds in some subset of proteins necessary for normal cell morphology. Intriguingly, the long filaments are reminiscent of the cell division defects associated with a misfolded FtsN, a protein confirmed to be a DsbA substrate (10). This phenotype was obvious in log phase (8 h), a point at which a ΔdsbA mutant strain showed defects in FtsN folding (10), but few filaments could be seen after cultures were allowed to continue to incubate overnight. Such a phenomenon suggests that these filaments could be resolved through the oxygen-dependent introduction of disulfide bonds and supports the finding that this oxidation rate is quite low.

We had hypothesized that dsb strains failed to grow anaerobically because one or more DsbA substrate was misfolded under these conditions. To identify which substrate might be responsible, we had hoped to isolate suppressor mutants that bypassed the requirement for this unknown substrate. While we were not successful in isolating such bypass mutants, we did isolate suppressing mutations in trxB and dsbC. These gene products normally play critical roles in the disulfide isomerization pathway, which serves as a quality control checkpoint for periplasmic disulfide bond formation (12). DsbA appears to be rather indiscriminate with regard to which cysteines in a given substrate it joins into disulfide bonds, although there seems to be a preference to join consecutive cysteines. For substrates requiring disulfide bonds between nonconsecutive cysteines, therefore, the isomerization pathway must reduce the incorrect disulfides so that the correct ones might be formed (21). To do this, the dimeric periplasmic isomerase DsbC must be in the reduced form, in contrast to the monomeric oxidase DsbA. The oxidative nature of the periplasm requires that electrons be shuttled from the cytoplasm to DsbC. Therefore, electrons are shuttled from TrxB to TrxA to the inner membrane protein DsbD, where they are donated to DsbC via a disulfide cascade (22, 23). Null mutations in trxA, trxB, or dsbD have been shown to prevent the reduction of DsbC (22), which allows DsbC then to catalyze disulfide bond formation rather than reduce such bonds (12).

Overexpression of dsbC has also been shown to overcome the sensitivity of a ΔdsbA mutant strain to dithiothreitol (DTT) by partially restoring disulfide bond formation, although this complementation occurred only in LB, a growth medium known to contain a relatively high concentration of cystine (6, 24). In contrast, point mutations in dsbC that render the protein incapable of dimerizing have been shown to restore disulfide bond formation to a ΔdsbA mutant strain in the absence of known small-molecule oxidants (14). These monomers of DsbC can bind to DsbB and thus be catalytically oxidized, unlike bulky dimers of DsbC, which cannot access DsbB's active site. One DsbC mutation shown to partially restore motility to a ΔdsbA mutant when overexpressed is G69R (14). This is the exact mutation we isolated in our anaerobic selection, along with A42E, which is also predicted to lie within or very near to the dimerization domain. We would therefore conclude that, like the trxB mutations, these mutations in dsbC suppress the anaerobic growth defect of the ΔdsbA mutant strain by partially restoring disulfide bond formation. However, none of the suppressor mutations restored motility to strains lacking dsbA or dsbB under anaerobic or aerobic conditions. This is in contrast to the previous studies, which expressed the DsbC variants from a plasmid. This suggests that the amount of the mutant DsbC is important to the overall restoration of disulfide bond formation.

The fact that we were unable to isolate spontaneous mutations that suppress the anaerobic growth defect of a ΔdsbA ΔdsbC mutant strain raises the prospect that it might not be possible to bypass the requirement for whatever DsbA substrate is essential for growth. LptD is known to require disulfide bonds, and we show here that it accumulates almost entirely in the reduced (inactive) state in a ΔdsbA mutant strain incubated anaerobically. The complex folding process required to activate LptD and insert it into the outer membrane suggests that perhaps multiple mutations in the protein would be necessary to overcome the folding defect, if it were at all possible. It may also be that more than one DsbA substrate is essential and absolutely requires a disulfide bond for activity. In support of such a notion, we have previously shown that the cell division protein FtsN also accumulates in the reduced inactive form in anaerobically challenged dsb mutants (10). Proper disulfide bond formation is therefore a critical process for both cell division and outer membrane assembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Potassium nitrate, sodium fumarate, dithiothreitol, and kanamycin were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Cystine and uracil were purchased from Calbiochem (Billerica, MA).

Strain construction.

All strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. NK312 was made by P1 transduction of ΔmalF::kanr from the Keio collection into strain AN384, which carries the ubiA420 allele. NK319 was made by transducing HK295 to kanamycin resistance, after which colonies were screened by PCR to confirm that the kanamycin resistance cassette was linked to the ubiA420 allele in this strain. NK299 was made by P1 transduction of ΔmenA::kanr from the Keio collection into HK295. The kanamycin resistance cassette was removed with the flippase encoded by pCP20, and the resulting deletion was confirmed via PCR. To create a strain disrupted in the production of both ubiquinone and menaquinone, P1 phage was grown on strain NK319 and transduced into NK299. Transductants were selected on LB containing 5 mM sodium citrate, 40 μg/ml kanamycin, and 1 mM 4-hydroxybenzoate. To confirm that these transductants were ubi men, colonies were tested for lack of growth on LB lacking 4-hydroxybenzoate. One colony that failed to grow without 4-hydroxybenzoate was saved as BOM633.

TABLE 2.

Strains used in this work

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| HK295 | MC1000 Δara714 leu+ | 25 |

| HK317 | HK295 ΔdsbA | 26 |

| HK320 | HK295 ΔdsbB | 25 |

| HK329 | HK295 ΔdsbA ΔdsbB | 27 |

| AN384 | ubiA420 | 28 |

| CL337 | HK295 LptD4213 | 30 |

| NK312 | AN384 ΔmalF::aph | This work |

| NK319 | HK295 ubiA420…ΔmalF::aph | This work |

| NK299 | HK295 ΔmenA | This work |

| BOM633 | HK295 ΔmenA ubiA*…ΔmalF::aph | This work |

Growth conditions.

Aerobic cultures were grown in M63 medium containing 0.2% glucose (M63glu) at 37°C in culture tubes on a rolling wheel. For anaerobic growth, M63glu containing 40 mM potassium nitrate (or 40 mM sodium fumarate) was degassed by boiling and immediately transferred into a Coy anaerobic chamber to equilibrate for at least 18 h before use. The anaerobic chamber contained 85% nitrogen, 10% hydrogen, and 5% carbon dioxide and was maintained at 37°C. BOM633 cultures were supplemented with 1 mM 4-hydroxybenzoate when grown aerobically and 0.2 mM uracil when grown anaerobically to bypass the function of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (29). LB (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl) plates were used for enumeration of CFU.

Growth curves.

Cultures were grown overnight in M63glu at 37°C and then diluted 1:50 into fresh medium. When cultures had reached log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], ∼0.3), they were diluted 1:250 into fresh medium to start the growth curve. Samples were taken over time, serially diluted, and plated aerobically onto LB with or without 1 mM 4-hydroxybenzoate. Plates were incubated aerobically overnight at 37°C, and CFU were enumerated the following day.

Selection of dsb suppressor mutants capable of anaerobic growth.

To select for a suppressor mutant capable of anaerobic growth in liquid medium, HK317 (ΔdsbA mutant) was grown aerobically at 37°C in M63glu to log phase and then diluted 1:1,000 into 500 ml of M63glu with 50 mM fumarate anaerobically. The culture was allowed to grow without shaking for 4 days at 37°C until dense growth could be seen. This culture was rediluted 1:1,000 into fresh medium and grown for 2 days anaerobically to ensure that the suppressor strain could maintain anaerobic growth through multiple passages. To select for suppressor mutants capable of growth on solid medium, M63glu plates containing 40 mM fumarate and solidified with 1% low electroendosmosis (LE) agarose (GeneMate, Kaysville, UT) were poured in the anaerobic chamber and allowed to solidify at room temperature. One hundred microliters of aerobically grown log-phase cultures of HK317 or HK320 (ΔdsbB mutant) was spread on these plates and allowed to incubate anaerobically at 37°C for 1 week. Colonies that arose were purified onto the same medium anaerobically and then grown in M63glu aerobically for preparation of DNA.

Identification of suppressor mutations.

DNA was prepared from the ΔdsbA mutant suppressor that grew anaerobically in liquid using the Wizard genomic prep kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Purified DNA was then sheared via sonication, and the ends were prepared and indexed with the NEBNext Ultra DNA library kit (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). DNA was cleaned up with PCRClean DX magnetic beads (Aline Biosciences, Woburn, MA), and 200-bp fragments were prepared as per the manufacturer's instruction. Fragments were PCR amplified using NEBNext multiplex oligonucleotides (New England BioLabs), per the manufacturer's protocol, and reaction mixtures were cleaned up with magnetic beads. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform by the Biopolymers Facility at Harvard Medical School. Fragments were mapped to the genome of strain MG1655 for comparison, and data analysis was performed using CLC Workbench. Since sequence analysis of this suppressor revealed a mutation in dsbC (see Results), all suppressors arising on anaerobic plates were sequenced across the dsbC locus using primers BAM82 (5′-TAAAGGATCTCAACGGCCTT-3′) and BAM83 (5′-ATGTGTTGCGTCACGCTTTT-3′) after PCR amplification using those same primers. We have previously found that mutations in trxB give rise to resistance to small-molecule inhibitors of DsbB (C. Landeta, unpublished data), so suppressors were also screened for mutations in trxB using primers BAM175 (5′-CTGCCGATTGCACAAATTGT-3′) and BAM176 (5′GCATGGTGTCGCCTTCTTTA-3′) after PCR amplification with those primers.

Microscopy.

To investigate the cellular morphology of strains grown with or without oxygen, 10-μl samples of cultures were spotted onto 1% agarose pads affixed to microscope slides and visualized using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy.

Immunoblotting.

Anti-LptD immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described, with slight modifications (16). The outer membrane fragments were obtained from 10-ml cultures of wild type (wt; HK295), LptD4213 (CL337), ΔdsbA mutant (HK317), ΔdsbB mutant (HK320), and dsbAsup (DsbCG69R) grown for 4 h in M63 minimal medium with 0.2% glucose in the presence or absence of oxygen, as indicated above. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 20 min and then resuspended in 5 ml of Tris-B buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) containing 20% (wt/wt) sucrose, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma), 50 μg/ml DNase I (Sigma), and 50 mM iodoacetamide (IAM; Sigma). Cells were lysed by sonication giving 5-on/1-off pulses of 30 s of 50% amplitude (QSonica sonicator). Approximately 8 ml of cell lysate was layered onto a two-step sucrose gradient (top 4 ml of Tris-B buffer containing 40% [wt/wt] sucrose, bottom 1 ml of Tris-B buffer containing 65% [wt/wt] sucrose) and centrifuged at 39,000 rpm for 16 h in a Beckman SW41 rotor in an ultracentrifuge (Beckman). OM fragments (∼0.5 ml) were isolated from the 40%/65% interface by puncturing the side of the tube with a syringe. One milliliter of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) was added to the OM fragments to lower the sucrose concentration to below 20% (wt/wt). The OM fragments were then pelleted in a microcentrifuge at 18,000 × g for 30 min and resuspended in 200 to 250 μl of Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 5 mM IAM. Proteins from outer membrane fragments were precipitated with 10% trifluoroacetic acid (TCA), washed with acetone, resuspended in TBS containing 2% SDS, and then heated for 10 min at 90°C. DTT was used to reduce the disulfide bonds only in control samples. The amount of protein was determined in diluted samples by Pierce bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Thermo Scientific). Proteins were analyzed by nonreducing SDS-PAGE (10% acrylamide) and immunoblotted against LptD (20).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Na Ke for strains NK299 and NK319 and William Robins for guidance in preparing samples for Illumina sequencing. We also thank Dan Kahne for kindly providing the LptD antibody.

This work was supported by U.S. National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant GMO41883 (to J.B.). B.M.M was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA fellowship (GM108443). C.L. was partially supported by a Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT) postdoctoral fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Derman AI, Beckwith J. 1991. Escherichia coli alkaline phosphatase fails to acquire disulfide bonds when retained in the cytoplasm. J Bacteriol 173:7719–7722. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.23.7719-7722.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill DM. 1977. Mechanism of action of cholera toxin. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Res 8:85–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dailey FE, Berg HC. 1993. Mutants in disulfide bond formation that disrupt flagellar assembly in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:1043–1047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz N, Chng S-S, Hiniker A, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. 2010. Nonconsecutive disulfide bond formation in an essential integral outer membrane protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:12245–12250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007319107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anfinsen CB. 1973. Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science 181:223–230. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4096.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bardwell JCA, McGovern K, Beckwith J. 1991. Identification of a protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Cell 67:581–589. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadokura H, Beckwith J. 2010. Mechanisms of oxidative protein folding in the bacterial cell envelope. Antioxid Redox Signal 13:1231–1246. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bader MW, Xie T, Yu CA, Bardwell JC. 2000. Disulfide bonds are generated by quinone reduction. J Biol Chem 275:26082–26088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003850200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heras B, Shouldice SR, Totsika M, Scanlon MJ, Schembri MA, Martin JL. 2009. DSB proteins and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:215–225. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meehan BM, Landeta C, Boyd D, Beckwith J. 2017. The essential cell division protein FtsN contains a critical disulfide bond in a non-essential domain. Mol Microbiol 103:413–422. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chng S-S, Dutton RJ, Denoncin K, Vertommen D, Collet J-F, Kadokura H, Beckwith J. 2012. Overexpression of the rhodanese PspE, a single cysteine-containing protein, restores disulphide bond formation to an Escherichia coli strain lacking DsbA. Mol Microbiol 85:996–1006. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rietsch A, Belin D, Martin N, Beckwith J. 1996. An in vivo pathway for disulfide bond isomerization in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:13048–13053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bardwell JC, Lee JO, Jander G, Martin N, Belin D, Beckwith J. 1993. A pathway for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:1038–1042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bader MW, Hiniker A, Regeimbal J, Goldstone D, Haebel PW, Riemer J, Metcalf P, Bardwell JC. 2001. Turning a disulfide isomerase into an oxidase: DsbC mutants that imitate DsbA. EMBO J 20:1555–1562. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denoncin K, Vertommen D, Paek E, Collet J-F. 2010. The protein-disulfide isomerase DsbC cooperates with SurA and DsbA in the assembly of the essential β-barrel protein LptD. J Biol Chem 285:29425–29433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chng S-S, Xue M, Garner RA, Kadokura H, Boyd D, Beckwith J, Kahne D. 2012. Disulfide rearrangement triggered by translocon assembly controls lipopolysaccharide export. Science 337:1665–1668. doi: 10.1126/science.1227215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scholten HJ, Pierik RLM. 1998. Agar as a gelling agent: chemical and physical analysis. Plant Cell Rep 17:230–235. doi: 10.1007/s002990050384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inaba K, Takahashi Y-H, Ito K. 2005. Reactivities of quinone-free DsbB from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 280:33035–33044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inaba K, Murakami S, Suzuki M, Nakagawa A, Yamashita E, Okada K, Ito K. 2006. Crystal structure of the DsbB-DsbA complex reveals a mechanism of disulfide bond generation. Cell 127:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun M, Silhavy TJ. 2002. Imp/OstA is required for cell envelope biogenesis in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 45:1289–1302. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berkmen M, Boyd D, Beckwith J. 2005. The nonconsecutive disulfide bond of Escherichia coli phytase (AppA) renders it dependent on the protein-disulfide isomerase, DsbC. J Biol Chem 280:11387–11394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rietsch A, Bessette P, Georgiou G, Beckwith J. 1997. Reduction of the periplasmic disulfide bond isomerase, DsbC, occurs by passage of electrons from cytoplasmic thioredoxin. J Bacteriol 179:6602–6608. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6602-6608.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katzen F, Beckwith J. 2000. Transmembrane electron transfer by the membrane protein DsbD occurs via a disulfide bond cascade. Cell 103:769–779. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00180-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Missiakas D, Georgopoulos C, Raina S. 1993. Identification and characterization of the Escherichia coli gene dsbB, whose product is involved in the formation of disulfide bonds in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:7084–7088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kadokura H, Beckwith J. 2002. Four cysteines of the membrane protein DsbB act in concert to oxidize its substrate DsbA. EMBO J 21:2354–2363. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.10.2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadokura H, Tian H, Zander T, Bardwell JCA, Beckwith J. 2004. Snapshots of DsbA in action: detection of proteins in the process of oxidative folding. Science 303:534–537. doi: 10.1126/science.1091724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eser M, Masip L, Kadokura H, Georgiou G, Beckwith J. 2009. Disulfide bond formation by exported glutaredoxin indicates glutathione's presence in the E. coli periplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:1572–1577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812596106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallace BJ, Young IG. 1977. Role of quinones in electron transport to oxygen and nitrate in Escherichia coli. Studies with a ubiA− menA− double quinone mutant. Biochim Biophys Acta 461:84–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seaver LC, Imlay JA. 2004. Are respiratory enzymes the primary sources of intracellular hydrogen peroxide? J Biol Chem 279:48742–48750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landeta C, Meehan BM, McPartland L, Ingendahl L, Hatahet F, Tran NQ, Boyd D, Beckwith J. 2017. Inhibition of virulence-promoting disulfide bond formation enzyme DsbB is blocked by mutating residues in two distinct regions. J Biol Chem 292:6529–6541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.770891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]