ABSTRACT

Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus is an increasing worldwide problem with major clinical implications. Surveillance is warranted to guide clinicians to provide optimal treatment to patients. To investigate azole resistance in clinical Aspergillus isolates in our institution, a Belgian university hospital, we conducted a laboratory-based surveillance between June 2015 and October 2016. Two different approaches were used: a prospective culture-based surveillance using VIPcheck on unselected A. fumigatus (n = 109 patients, including 19 patients with proven or probable invasive aspergillosis [IA]), followed by molecular detection of mutations conferring azole resistance, and a retrospective detection of azole-resistant A. fumigatus in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid using the commercially available AsperGenius PCR (n = 100 patients, including 29 patients with proven or probable IA). By VIPcheck, 25 azole-resistant A. fumigatus specimens were isolated from 14 patients (12.8%). Of these 14 patients, only 2 had proven or probable IA (10.5%). Mutations at the cyp51A gene were observed in 23 of the 25 A. fumigatus isolates; TR34/L98H was the most prevalent mutation (46.7%), followed by TR46/Y121F/T289A (26.7%). Twenty-seven (27%) patients were positive for the presence of Aspergillus species by AsperGenius PCR. A. fumigatus was detected by AsperGenius in 20 patients, and 3 of these patients carried cyp51A mutations. Two patients had proven or probable IA and cyp51A mutation (11.7%). Our study has shown that the detection of azole-resistant A. fumigatus in clinical isolates was a frequent finding in our institution. Hence, a rapid method for resistance detection may be useful to improve patient management. Centers that care for immunocompromised patients should perform routine surveillance to determine their local epidemiology.

KEYWORDS: VIPcheck, AsperGenius, cyp51A, cyp51B, hapE

INTRODUCTION

Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus is an emerging problem worldwide, with major epidemiological and clinical implications (1–6). Mold active triazoles are commonly used as first line treatment and prophylaxis of invasive aspergillosis (IA) (7). Mutations in the cyp51A gene, which encodes the target of azoles, the lanosterol 14α-demethylase, represent the most commonly reported mechanism conferring azole resistance and consequently treatment failure in A. fumigatus (8–10). The most prevalent mutation (TR34/L98H) involves the insertion of a 34-bp tandem repeat (TR34) in the promoter region of the cyp51A gene and a point mutation within the gene leading to an amino acid substitution (L98H). More recently, an additional cyp51A-mediated resistant genotype (TR46/Y121F/T289A) has been reported: a 46-bp tandem repeat (TR46) in the promoter of cyp51A gene and two point mutations within the gene (Y121F/T289A) (11–13). Other point mutations in the cyp51A gene are also responsible for azole resistance. For example, prolonged exposition to azole treatment is associated with selective pressure, resulting in the emergence of azole-resistance mediated by point mutations (10–14). Furthermore, A. fumigatus azole-resistant strains have also been isolated from azole-naive patients and from the environment due to mutant selection (mainly TR34/L98H and TR46/Y121F/T289A) caused by the use of fungicides in agriculture, as confirmed by molecular typing (12, 15).

Several studies performed in Belgium and in the Netherlands, a neighboring country, have reported the presence of azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates both in patients and in the environment (16–18). A clinical case of IA due to A. fumigatus containing the TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation in the cyp51A gene was detected in 2013 for the first time at Erasme Hospital in Brussels, Belgium (19). In order to investigate the occurrence of azole-resistant A. fumigatus at Erasme Hospital, resistance surveillance has been performed between June 2015 and October 2016 in the patient population attending to this Belgian University hospital. Two different approaches were used: a prospective culture-based surveillance of unselected azole-resistant A. fumigatus and a retrospective direct detection of azole-resistant A. fumigatus in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) specimens by using the commercially available AsperGenius PCR (Pathognostic, Maastrich, The Netherlands). Furthermore, we report the performance of AsperGenius PCR to diagnose proven and probable IA compared to an in-house-developed PCR and culture methods.

RESULTS

Mycological cultures and susceptibility testing by azole resistance screening.

A total of 212 positive samples for A. fumigatus were isolated from 109 hospitalized patients' respiratory specimens, including 116 sputum samples, 51 bronchopulmonary aspirate samples, 41 BAL fluid samples, 2 pleural fluid samples, and 2 pulmonary biopsy specimens. Most prevalent underlying diseases among these 109 patients were as follows: 23% (n = 25) were cystic fibrosis patients, 21% (n = 23) were lung transplant patients, and 13% (n = 14) had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Four of the 23 lung transplant recipients had undergone a lung transplant due to the cystic fibrosis. Seventeen percent of the patients were diagnosed with proven (n = 5) or probable (n = 14) IA, 4% (n = 5) with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, and the remaining 78% of patients (n = 85) were considered to be colonized by A. fumigatus.

The 212 A. fumigatus isolates recovered from respiratory specimens were screened by VIPcheck: 25 specimens from 14 patients had azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates, translating into a prevalence of azole resistance of 12.8% (14 of 109) among patients and of 10.5% (2 of 19) among patients with proven or probable IA. Resistance genotyping was then performed. Mutations at the cyp51A gene were observed in 23 A. fumigatus isolates from 12 patients, while no missense mutations were observed in two cases. MICs, resistance genotyping results, and clinical and demographic data from patients harboring azole-resistant A. fumigatus are summarized in Table 1. Genotyping allowed us to determine the presence of one or two isogenic strains per patient: 15 different strains were obtained from 14 patients. Among these 15 strains, the TR34/L98H was the most prevalent mutation (46.7%), followed by TR46/Y121F/T289A (26.7%). An isolate with a TR34/L98H mutation from one patient showed also a deletion of eight nucleotides in the cyp51B promoter. No isolates showed mutations in hapE.

TABLE 1.

cyp51A mutations, MIC results, and demographic data from patients (n = 14) harboring azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolated at Erasme Hospital as detected by VIPcheck from June 2015 to October 2016

| Patient | Age (yr) | Underlying disease | Sourcea | Colonization/IA | Prior azole exposition | MIC (mg/liter)b |

cyp51A mutation(s) (no. of isolates)c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITC | VRC | POS | |||||||

| 1 | 39 | Cystic fibrosis | BA/S | Colonization | VRZ, ITZ | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | TR34/L98H (5) |

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.25 | G448S (2) | ||||||

| 2 | 81 | Solid malignancy | BA/S | Colonization | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | ||

| 3 | 53 | Hematological malignancy | BA/S | Colonization | POS | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | TR34/L98H |

| 4 | 47 | Cystic fibrosis | BA/S | Colonization | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| 5 | 18 | Cystic fibrosis | BA/S | Colonization | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | TR34/L98H | |

| 6 | 26 | Intestinal malabsorption | BA/S | Colonization | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | TR34/L98H | |

| 7 | 67 | Lung transplant | BAL | Probable IA | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | TR34/L98H | |

| 8 | 58 | Heart transplant | BAL | Probable IA | VRZ | 0.5 | >8 | 0.5 | TR46/Y121F/T289A |

| 9 | 26 | Cystic fibrosis | BA/S | Colonization | 0.5 | >8 | 0.5 | TR46/Y121F/T289A | |

| 10 | 86 | Solid malignancy | BA/S | Colonization | 16 | 1 | 1 | TR34/L98Hd | |

| 11 | 66 | COPD | BAL | Colonization | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | TR34/L98H (2) | |

| 12 | 48 | Lung transplant | BA/S | Colonization | VRZ | 0.5 | >8 | 0.5 | N248K |

| 13 | 55 | Lung transplant | BA/S | Colonization | VRZ | 0.5 | >8 | 0.5 | TR46/Y121F/T289A (5) |

| 14 | 65 | Lung transplant | BA/S | Colonization | 0.5 | >8 | 0.25 | TR46/Y121F/T289A | |

BA/S, bronchial aspirate or sputum; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

ITC itraconazole; VRC, voriconazole; POS, posaconazole.

The number of isolates when more than one strain was recovered with the same characteristics is indicated within parentheses.

A deletion of eight nucleotides in the cyp51B promoter was also observed for this isolate.

Regarding the patients with proven or probable IA, a 58-year-old heart transplant patient with a probable IA during a neutropenic episode harbored first an A. fumigatus wild type. After 5 weeks of treatment with voriconazole, A. fumigatus TR46/Y121F/T289 was detected. The patient was treated with voriconazole for 6 weeks in all and cured despite the mutations at cyp51A. The other patient harboring A. fumigatus TR34/L98H, was a 67-year-old lung transplant recipient diagnosed with probable IA and treated and cured with voriconazole associated with caspofungin.

AsperGenius PCR.

Twenty-seven patients (27%) were determined to be positive by AsperGenius for Aspergillus species detection using a standard threshold cycle (CT) value of <36. More specifically, A. fumigatus was detected in 20 patients, and 3 of them (15%) harbored cyp51A mutations. Two of these patients were already detected for azole resistance by culture-based screening (see above). The remaining case was a patient with a galactomannan (GM)-negative BAL fluid sample, probably colonized by A. fumigatus TR34/L98H. However, mycological cultures for this patient were negative. Among these 27 patients, a total of 19 patients were diagnosed with proven or probable IA, 47% of whom were lung transplant recipients. The resistance frequency of A. fumigatus detected by AsperGenius among patients with proven or probable IA was 11.7% (2/17).

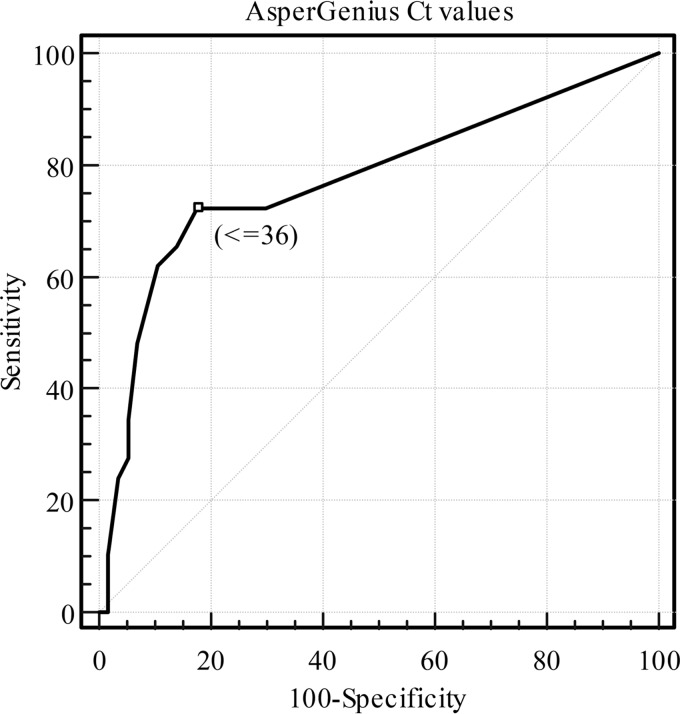

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for AsperGenius showed an optimal cutoff CT value of ≤36 (Fig. 1). Considering the EORTC/MSG (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infection Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group) definitions for clinical classification as the gold standard, the sensitivity and specificity for AsperGenius (CT values of <36 and ≤36), in-house PCR, and mycological culture for diagnosis of IA are shown in Table 2. The sensitivity and specificity of AsperGenius using the standard CT value were 65.5% (95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 48.2 to 82.8%) and 86% (95% CI = 76.9 to 95%), respectively (Table 3).

FIG 1.

ROC curve for AsperGenius CT results.

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients included in the AsperGenius evaluation study and results of AsperGenius, in-house PCR, galactomannan antigen detection, and cultures

| EORTC/MSG classification and underlying disease (n)a | AsperGenius PCR (n)b | In-house PCR (n)c | GM (n)d | Culture and cyp51A genotype (n)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proven IA (5) | ||||

| Lung transplantation (3) | A. fumigatus WT7 (5) | 5 | 5 | A. fumigatus WT (5) |

| Sarcoidosis (1) | ||||

| Acute alcoholic hepatitis (1) | ||||

| Probable IA (24) | ||||

| Lung transplantation (10) | A. fumigatus WT (10) | A. fumigatus WT (8) | ||

| Hematological malignancy (5) | A. fumigatus TR46/Y121F/T289A (1) | 14 | 24 | A. fumigatus TR46/Y121F/T289A (1) |

| Solid malignancy (3) | A. fumigatus TR34/L98H (1) | A. fumigatus TR34/L98H (1) | ||

| Acute alcoholic hepatitis (2) | Aspergillus spp. (2) | A. flavus (1) | ||

| Others (4) | ||||

| Possible IA (14) | ||||

| Hematological malignancy (4) | ||||

| Lung transplantation (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Solid malignancy (2) | ||||

| Acute alcoholic hepatitis (2) | ||||

| Others (4) | ||||

| Unclassifiable (57) | ||||

| Autoimmune disease (9) | ||||

| COPD (9) | ||||

| Lung transplantation (7) | ||||

| Solid malignancy (4) | A. fumigatus WT (2) | |||

| Liver cirrhosis (4) | A. fumigatus TR34/L98H (1) | 8 | 16 | A. fumigatus WT (1) |

| Ischemic heart disease (3) | Aspergillus spp. (5) | A. niger (2) | ||

| Liver transplantation (1) | ||||

| Others (13) | ||||

| No underlying diseases (7) |

EORTC/MSG, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group; n, number of patients in each category. A total of four lung transplant patients were diagnosed with cystic fibrosis.

That is, the number of patients determined to be positive with the AsperGenius PCR for Aspergillus (cutoff CT value of <36) and resistance detection. WT, wild type without cyp51A mutations.

n, the number of patients determined to be positive with the in house real-time PCR (cutoff CT value of <45).

n, the number of patients determined to be positive for galactomannan (GM) antigen detection (OD index ≥1).

n, the number of mycological cultures positive for Aspergillus spp. and cyp51A genotypes. WT, wild type without cyp51A mutations.

TABLE 3.

Clinical performance of AsperGenius, in-house PCR, and culture, considering EORTC/MSG definitions for clinical classification of invasive aspergillosis as the gold standard

| Technique (CT) | % Sensitivity or specificity (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| AsperGenius PCR | ||

| <36 | 65.5 (48.2–82.8) | 86 (76.9–95) |

| ≤36 | 72.4 (52.8–87.2) | 82.5 (70.1–91.2) |

| In-house PCR (<45) | 65.5 (48.2–82.8) | 86 (76.9–95) |

| Culture | 58.6 (40.7–76.5) | 94.7 (88.9–100) |

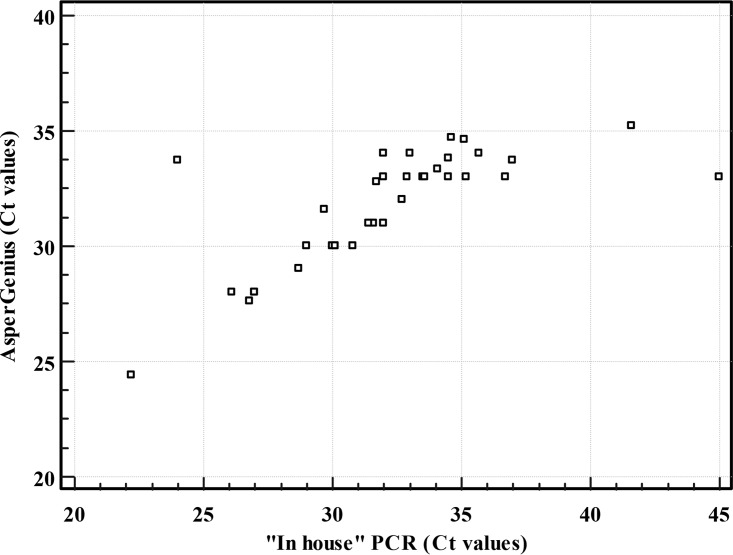

Excellent agreement and correlation between AsperGenius and the in-house PCR results for Aspergillus detection were observed independently of the cutoff CT value used (Fig. 2). By using a standard CT value (<36) for AsperGenius, the correlation with the in-house PCR generated a kappa statistic of 0.85 (95% CI = 0.73 to 0.96) and a Spearman coefficient of r = 0.81 (95% CI = 0.61 to 0.91; P < 0.001). By using the optimal CT value (≤36) for AsperGenius, the correlation with the in-house PCR generated a kappa statistic of 0.80 (standard error = 0.066; 95% CI = 0.67 to 0.93) and a Spearman coefficient of r = 0.79 (95% CI = 0.57 to 0.9; P < 0.001).

FIG 2.

Scatter diagram showing correlation between cycle threshold values (CT) obtained by AsperGenius (CT < 36) and in-house PCR (CT < 45).

DISCUSSION

Invasive aspergillosis due to azole-resistant isolates is a growing concern in the clinical setting (20). Two approaches have been used in this study to assess this problem in our institution. The first approach was a prospective culture-based surveillance of unselected azole-resistant A. fumigatus, and the second approach was a retrospective direct detection of azole-resistant A. fumigatus in BAL fluid specimens by using AsperGenius PCR, a commercial real-time PCR that detects Aspergillus spp. and simultaneously identifies the most prevalent cyp51A mutations in A. fumigatus. The two approaches both showed an alarmingly high frequency of azole resistance occurrences among patients with proven or probable IA in our institution.

The prospective culture-based surveillance of unselected azole-resistant A. fumigatus and screening with VIPcheck identified a high prevalence of azole-resistance among all patients (approximately 13%) and among patients with probable or proven IA (approximately 11%). Similar surveillance studies in unselected isolates have shown a lower prevalence of azole-resistant A. fumigatus among patients, such as 1.8% in France and 2.1% in Denmark (21, 22). Furthermore, van der Linden et al. (4) reported an overall prevalence of 3.2% of azole-resistant A. fumigatus among patients in a prospective international surveillance study conducted in 19 countries, the majority of them being European. Similarly, the prevalence of azole-resistant A. fumigatus in a Belgian multicenter prospective cohort of patients with Aspergillus disease was 5.5% (17). Higher prevalences (8 to 30%) have been reported in other surveillance studies and particularly in those involving hematological and intensive care unit patients (10, 23–25). The prevalence of resistance may vary between units, hospitals, and geographical regions. To explain these variations, the bias related to laboratory procedures or the surveillance systems applied has to be considered (26, 27). The higher prevalence observed in the present study can be due to the different patient populations investigated. Here, hematological patients represented only 8% of the cohort, whereas cystic fibrosis and lung transplant patients accounted for nearly 50% of the population investigated. The prevalences of azole resistance among cystic fibrosis and lung transplant patients were 16 and 17%, respectively. Indeed, other studies in cystic fibrosis patients have shown prevalences of azole resistance in A. fumigatus varying between 0 and 20%, depending on previous azole exposure. Nevertheless, a prevalence of approximately 5% is the most common in this population (28–32). In the present study, TR34/L98H was the most frequent mutation observed, as has been observed in other studies (4, 23–25, 31).

AsperGenius PCR was tested retrospectively in the same period of the study in order to detect Aspergillus spp in BALs. The performance of AsperGenius for identifying patients with probable or proven IA was identical with the in-house PCR when a standard CT value (<36) was applied and slightly better than the culture. A better sensitivity was found when a cutoff CT value of ≤36 was used following ROC curve results. A similar clinical performance for the AsperGenius assay was determined in other studies (33–36). Chong et al. (34) favored a cutoff value of ≤38 to increase sensitivity to 84% without harming specificity, while in another study a cutoff value of 39 was chosen for testing AsperGenius in serum samples (35). Diagnostic performances of Aspergillus PCRs in the literature are often contradictory and difficult to compare, mainly because of differences in the protocols used. Some meta-analysis and reviews have shown sensitivities and specificities also around 76 to 79% and 93 to 94%, respectively, when BAL specimens were tested (37–39).

AsperGenius identified similar azole resistance occurrences among patients with proven or probable IA compared to VIPcheck. The advantage of AsperGenius is the combination of a sensitive method with the detection of resistance in the same test. Culture-based methods are theoretically less sensitive and slower than molecular methods, essentially due to the well-reported poor sensitivity of culture for IA diagnosis (40). However, culture-based methods are cheaper than molecular methods, and they allow the identification of new resistance mutations and trends. Moreover, unselected culture of different respiratory samples from the same patient could improve the detection of azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates in patients at high risk for IA.

In the past, microbial surveillance systems have improved infection control by helping acquire knowledge concerning risk factors, trends in resistance, and how to improve therapeutics (41). A recently published international expert opinion on the management of infection due to azole-resistant A. fumigatus recommends reconsidering azole monotherapy in regions where azole resistance rates exceed 10% (42). However, some authors consider that before making decisions on therapeutics, a harmonization of surveillance approaches in terms of mycological procedures and/or the use of an appropriate denominator is required (27, 28).

This study has some limitations since the AsperGenius method was performed retrospectively, and not all GM-negative samples in the study period were included. Therefore, we do not know the exact azole resistance frequency over this period of time. However, this does not change the high azole frequency observed in patients with proven or probable IA.

In conclusion, a high level of azole resistance (>10%) was found at Erasme Hospital in unselected clinical respiratory specimens positive for A. fumigatus and among patients with proven and probable IA, regardless of the method used: unselected A. fumigatus culture-based screening by VIPcheck and direct detection of azole-resistant A. fumigatus by AsperGenius. These methods could be combined for resistance surveillance and diagnosis in hospitals with a high risk of IA. For clinical decisions concerning management of patients with azole-resistant IA, harmonization of azole resistance surveillance systems is required. Further surveillance of azole resistance in A. fumigatus at Erasme Hospital is warranted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture-based study on resistance mechanisms. (i) Clinical samples.

This study took place at Erasme Hospital, an 858-bed university hospital in Brussels, Belgium. All culture-positive respiratory samples for A. fumigatus were prospectively screened for azole resistance from June 2015 to October 2016.

(ii) Mycological cultures.

Respiratory specimens were processed and inoculated on Sabouraud dextrose sheep agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (bioTRADING, Mijdrecht, The Netherlands). The inoculated plates were incubated at 35°C for at least 15 days. Aspergillus isolates were identified first by microscopic and then by macroscopic morphological methods and confirmed by β-tubulin sequencing (43).

(iii) Susceptibility testing by azole resistance screening.

All A. fumigatus isolates were screened for azole resistance on VIPcheck (Balis Laboratorium, Boven-Leeuwen, The Netherlands). These plates contain four wells with itraconazole (4 mg/liter), voriconazole (1 mg/liter), posaconazole (0.5 mg/liter), or no antifungal agent (growth control well). In each well, 25 μl of a suspension with a turbidity standard of 0.5 McFarland (prepared with four to five colonies of A. fumigatus) was inoculated. All isolates able to grow on at least one of the azole-containing wells were further investigated for their MICs by Sensititre YeastOne (Trek Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, OH) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Epidemiological cutoffs based on Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines were used for the interpretation of the MIC values (0.5 μg/ml for posaconazole and 1 μg/ml for voriconazole and itraconazole) (44).

(iv) Resistance genotyping.

The promoter and/or full coding sequences of cyp51A, cyp51B, and hapE were amplified using primers and conditions previously described (8, 9, 14, 45). Amplicons were obtained by using the PCR master mix Promega (Promega Benelux, Leiden, The Netherlands) and later purified with an illustra ExoStar 1-Step kit (GE Healthcare Europe, Diegem, Belgium). Custom primers were designed to sequence each entire gene. Sequencing was performed by using a Dye Terminator DNA sequencing kit (v1.1; Applied Biosystems), followed by purification using a Performa DTR Ultra 96-well plate kit (Edge Bio, Gaithersburg, MD). Sequences were assembled and analyzed using BioNumerics 7.6 software (Applied Maths NV, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). The sequences obtained were compared to cyp51A (AF338659), cyp51B (AF338660), and hapE (CM000174) sequences of reference strains from the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/index.html).

Evaluation of AsperGenius PCR. (i) Clinical samples.

BALs from 489 hospitalized patients were tested for galactomannan (GM) antigen detection (Platelia Aspergillus; Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) between June 2015 and October 2016. GM was considered positive at an optical density (OD) index cutoff value of ≥1. A retrospective selection of the BALs analyzed during that period was performed in order to include 100 hospitalized patients: all patients with GM positive BALs (n = 45), as well as the first 55 patients with GM-negative BAL specimens (12%). When the BAL specimens were assessed, three aliquots of 50 ml were sampled and diluted in saline. The second and third aliquots were sent to the microbiology laboratory for GM analysis and culture.

(ii) DNA extraction of BAL specimens.

DNA was extracted from 800-μl BAL samples (elution volume, 60 μl) with a QIAsymphony DSP Virus/Pathogen Midi kit (Qiagen, Westburg, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

(iii) AsperGenius PCR.

The commercially available AsperGenius assay is a PCR that targets Aspergillus species DNA (including specific detection of A. fumigatus and Aspergillus terreus) in combination with the detection of the most prevalent mutations (TR34/L98H and TR46/Y121F/T289A) conferring azole resistance. This real-time PCR was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions using a LC480 sequence detector system. A CT cutoff value of <36 for the Aspergillus probe is recommended by the manufacturer.

The performance of this commercial PCR assay to diagnose IA was compared to mycological culture results and an “in-house”-developed PCR on the QuantStudio Dx (Qiagen) using primers and probe as described in the literature (46, 47). The PCR mix contained 7.5 μl pf TaqMan Fast Virus Mix (Life Technologies), primers (0.25 μmol/liter), probe (20 μmol/liter), internal control primers and probe for detection of inhibition (0.1 μmol/liter, template Phocine herpesvirus 1), and 10 μl of DNA template in a total volume of 30 μl. PCR conditions were one cycle of 95°C for 20 s, followed by up to 45 cycles of 95°C for 3 s and finally 60°C for 30 s, while acquiring the fluorescence data each cycle.

Patients and clinical aspects.

All patient characteristics were acquired retrospectively by reviewing medical charts including age, gender, underlying disease, immunosuppressive therapy, antifungal treatment, laboratory results, radiological presentation, and final clinical diagnosis. Patients were classified as having proven, probable or possible IA according to the revised EORTC/MSG definitions. Briefly, proven IA is defined as the demonstration of fungal elements in diseased tissue. Probable IA requires a host factor, clinical features, and mycological evidence of infection. Finally, possible IA are patients with appropriate host factors, with sufficient clinical evidence consistent with IA, but for whom mycological evidence is lacking. Host factors are the characteristics by which individuals predisposed to acquire IA can be recognized. Patients with host factors include those with cancer, recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplants, recipients of solid-organ transplants, patients with hereditary immunodeficiencies, patients with connective tissue disorders, and those who are treated with immunosuppressive agents (corticosteroids or T cell immunosuppressants) (48). Patients who could not be included in these three categories were defined as unclassifiable. Classification was performed by an infectious disease physician with experience in infectious lung disease in immunocompromised hosts and who was blind to PCR results.

Statistical analysis.

An ROC curve was constructed and used to define AsperGenius optimal cutoff CT values for IA diagnosis. Correlation between the two real-time PCR results was analyzed by Spearman coefficient rank correlation test. The sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing IA were calculated for each real-time PCR performed in this study and for the culture method. EORTC/MSG clinical classification was considered as the gold standard; proven and probable IA were considered true positives. Patients who did not meet the EORTC/MSG clinical criteria for proven and probable IA and who were not treated with antifungals were considered true negatives. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed by using the MedCalc software (Mariakerke, Belgium).

Accession number(s).

The cyp51A, cyp51B, and hapE sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank (nucleotide accession numbers MF070870 to MF070914).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by internal funding.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meis JF, Chowdhary A, Rhodes JL, Fisher MC, Verweij PE. 2016. Clinical implications of globally emerging azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 5:371. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagiwara D, Takahashi H, Fujimoto M, Sugahara M, Misawa Y, Gonoi T, Itoyama S, Watanabe A, Kamei K. 2016. Multi-azole resistant Aspergillus fumigatus harboring Cyp51A TR46/Y121F/T289A isolated in Japan. J Infect Chemother 22:577–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vazquez JA, Manavathu EK. 2015. Molecular characterization of a voriconazole-resistant, posaconazole-susceptible Aspergillus fumigatus isolate in a lung transplant recipient in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:1129–1133. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01130-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Linden JW, Arendrup MC, Warris A, Lagrou K, Pelloux H, Hauser PM, Chryssanthou E, Mellado E, Kidd SE, Tortorano AM, Dannaoui E, Gaustad P, Baddley JW, Uekötter A, Lass-Flörl C, Klimko N, Moore CB, Denning DW, Pasqualotto AC, Kibbler C, Arikan-Akdagli S, Andes D, Meletiadis J, Naumiuk L, Nucci M, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2015. Prospective multicenter international surveillance of azole resistance Aspergillus fumigatus. Emerg Infect Dis 21:1041–1044. doi: 10.3201/eid2106.140717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidd SE, Goeman E, Meis JF, Slavin MA, Verweij PE. 2015. Multi-triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus infections in Australia. Mycoses 58:350–355. doi: 10.1111/myc.12324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seyedmousavi S, Hashemi SJ, Zibafar E, Zoll J, Hedayati MT, Mouton JW, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2013. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus, Iran. Emerg Infect Dis 19:832–834. doi: 10.3201/eid1905.130075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ, Denning DW, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, van Burik JA, Wingard JR, Patterson TF. 2008. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 46:327–360. doi: 10.1086/525258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellado E, Diaz-Guerra TM, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. 2001. Identification of two different 14-alpha sterol demethylase-related genes (cyp51A and cyp51B) in Aspergillus fumigatus and other Aspergillus species. J Clin Microbiol 39:2431–2438. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2431-2438.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz-Guerra TM, Mellado E, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. 2003. A point mutation in the 14alpha-sterol demethylase gene cyp51A contributes to itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:1120–1124. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.3.1120-1124.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard SJ, Cerar D, Anderson MJ, Albarrag A, Fisher MC, Pasqualotto AC, Laverdiere M, Arendrup MC, Perlin DS, Denning DW. 2009. Frequency and evolution of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus associated with treatment failure. Emerg Infect Dis 15:1068–1076. doi: 10.3201/eid1507.090043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellado E, Garcia-Effron G, Alcázar-Fuoli L, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodríguez-Tudela JL. 2007. A new Aspergillus fumigatus resistance mechanism conferring in vitro cross-resistance to azole antifungals involves a combination of cyp51A alterations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:1897–1904. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01092-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Linden JW, Camps SM, Kampinga GA, Arends JP, Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Haas PJ, Rijnders BJ, Kuijper EJ, van Tiel FH, Varga J, Karawajczyk A, Zoll J, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2013. Aspergillosis due to voriconazole highly resistant Aspergillus fumigatus and recovery of genetically related resistant isolates from domiciles. Clin Infect Dis 57:513–520. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Hagen F, Meis JF. 2014. Exploring azole antifungal drug resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus with special reference to resistance mechanisms. Future Microbiol 9:697–711. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camps SM, van der Linden JW, Li Y, Kuijper EJ, van Dissel JT, Verweij PE, Melchers WJ. 2012. Rapid induction of multiple resistance mechanisms in Aspergillus fumigatus during azole therapy: a case study and review of the literature. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:10–16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05088-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verweij PE, Snelders E, Kema GH, Mellado E, Melchers WJ. 2009. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: a side-effect of environmental fungicide use? Lancet Infect Dis 9:789–795. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Passen J, Russcher A, in ‘t Veld-van Wingerden AW, Verweij PE, Kuijper EJ. 2016. Emerging aspergillosis by azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus at an intensive care unit in the Netherlands, 2010 to 2013. Euro Surveill 21:30. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.30.30300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vermeulen E, Maertens J, De Bel A, Nulens E, Boelens J, Surmont I, Mertens A, Boel A, Lagrou K. 2015. Nationwide surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus diseases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4569–4576. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00233-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vermeulen E, Maertens J, Schoemans H, Lagrou K. 2012. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus due to TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation emerging in Belgium, July 2012. Euro Surveill 17:pii20326 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montesinos I, Dodemont M, Lagrou K, Jacobs F, Etienne I, Denis O. 2014. New case of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus due to TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation in Belgium. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:3439–3440. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Linden JW, Snelders E, Kampinga GA, Rijnders BJ, Mattsson E, Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Kuijper EJ, Van Tiel FH, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2011. Clinical implications of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus, The Netherlands, 2007-2009. Emerg Infect Dis 17:1846–1854. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choukri F, Botterel F, Sitterlé E, Bassinet L, Foulet F, Guillot J, Costa JM, Fauchet N, Dannaoui E. 2015. Prospective evaluation of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates in France. Med Mycol 53:593–596. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myv029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen RH, Hagen F, Astvad KM, Tyron A, Meis JF, Arendrup MC. 2016. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in Denmark: a laboratory-based study on resistance mechanisms and genotypes. Clin Microbiol Infect 22:570.e1–570.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snelders E, van der Lee HA, Kuijpers J, Rijs AJ, Varga J, Samson RA, Mellado E, Donders AR, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2008. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS Med 5:e219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinmann J, Hamprecht A, Vehreschild MJ, Cornely OA, Buchheidt D, Spiess B, Koldehoff M, Buer J, Meis JF, Rath PM. 2015. Emergence of azole-resistant invasive aspergillosis in HSCT recipients in Germany. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:1522–1526. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuhren J, Voskuil WS, Boel CH, Haas PJ, Hagen F, Meis JF, Kusters JG. 2015. High prevalence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from high-risk patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2894–2898. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verweij PE, Lestrade PP, Melchers WJ, Meis JF. 2016. Azole resistance surveillance in Aspergillus fumigatus: beneficial or biased? J Antimicrob Chemother 71:2079–2082. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alanio A, Denis B, Hamane S, Raffoux E, Peffault de la Tour R, Touratier S, Bergeron A, Bretagne S. 2016. New therapeutic strategies for invasive aspergillosis in the era of azole resistance: how should the prevalence of azole resistance be defined? J Antimicrob Chemother 71:2075–2078. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgel PR, Paugam A, Hubert D, Martin C. 2016. Aspergillus fumigatus in the cystic fibrosis lung: pros and cons of azole therapy. Infect Drug Resist 20:229–238. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S63621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer J, van Koningsbruggen-Rietschel S, Rietschel E, Vehreschild MJ, Wisplinghoff H, Krönke M, Hamprecht A. 2014. Prevalence and molecular characterization of azole resistance in Aspergillus spp. isolates from German cystic fibrosis patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:1533–1536. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burgel PR, Baixench MT, Amsellem M, Audureau E, Chapron J, Kanaan R, Honoré I, Dupouy-Camet J, Dusser D, Klaassen CH, Meis JF, Hubert D, Paugam A. 2012. High prevalence of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in adults with cystic fibrosis exposed to itraconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:869–874. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05077-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bader O, Weig M, Reichard U, Lugert R, Kuhns M, Christner M, Held J, Peter S, Schumacher U, Buchheidt D, Tintelnot K, Gross U, MykoLabNet Partners. 2013. cyp51A-based mechanisms of Aspergillus fumigatus azole drug resistance present in clinical samples from Germany. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3513–3517. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00167-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mortensen KL, Jensen RH, Johansen HK, Skov M, Pressler T, Howard SJ, Leatherbarrow H, Mellado 2011. Aspergillus species and other molds in respiratory samples from patients with cystic fibrosis: a laboratory-based study with focus on Aspergillus fumigatus azole resistance. J Clin Microbiol 49:2243–2251. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00213-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chong GL, van de Sande WW, Dingemans GJ, Gaajetaan GR, Vonk AG, Hayette MP, van Tegelen DW, Simons GF, Rijnders BJ. 2015. Validation of a new Aspergillus real-time PCR assay for direct detection of Aspergillus and azole resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J Clin Microbiol 53:868–874. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03216-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chong GM, van der Beek MT, von dem Borne PA, Boelens J, Steel E, Kampinga GA, Span LF, Lagrou K, Maertens JA, Dingemans GJ, Gaajetaan GR, van Tegelen DW, Cornelissen JJ, Vonk AG, Rijnders BJ. 2016. PCR-based detection of Aspergillus fumigatus Cyp51A mutations on bronchoalveolar lavage: a multicentre validation of the AsperGenius assay in 201 patients with haematological disease suspected for invasive aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:3528–3535. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White PL, Posso RB, Barnes RA. 2015. Analytical and clinical evaluation of the PathoNostics AsperGenius Assay for detection of invasive aspergillosis and resistance to azole antifungal drugs during testing of serum samples. J Clin Microbiol 53:2115–2121. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00667-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White PL, Wingard JR, Bretagne S, Löffler J, Patterson TF, Slavin MA, Barnes RA, Pappas PG, Donnelly JP. 2015. Aspergillus polymerase chain reaction: systematic review of evidence for clinical use in comparison with antigen testing. Clin Infect Dis 61:1293–1303. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tuon FF. 2007. A systematic literature review on the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from bronchoalveolar lavage clinical samples. Rev Iberoam Micol 24:89–94. doi: 10.1016/S1130-1406(07)70020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun W, Wang K, Gao W, Su X, Qian Q, Lu X, Song Y, Guo Y, Shi Y. 2011. Evaluation of PCR on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: a bivariate meta-analysis and systematic review. PLoS One 6:e28467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avni T, Levy I, Sprecher H, Yahav D, Leibovici L, Paul M. 2012. Diagnostic accuracy of PCR alone compared to galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: a systematic review. J Clin Microbiol 50:3652–3658. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00942-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hope WW, Walsh TJ, Denning DW. 2005. Laboratory diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. Lancet Infect Dis 5:609–622. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70238-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Brien TF, Stelling J. 2011. Integrated multilevel surveillance of the world's infecting microbes and their resistance to antimicrobial agents. Clin Microbiol Rev 24:281–295. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00021-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verweij PE, Ananda-Rajah M, Andes D, Arendrup MC, Brüggemann RJ, Chowdhary A, Cornely OA, Denning DW, Groll AH, Izumikawa K, Kullberg BJ, Lagrou K, Maertens J, Meis JF, Newton P, Page I, Seyedmousavi S, Sheppard DC, Viscoli C, Warris A, Donnelly JP. 2015. International expert opinion on the management of infection caused by azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus. Drug Resist Updat 21–22:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Wathiqi F, Ahmad S, Khan Z. 2013. Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility profile of Aspergillus flavus isolates recovered from clinical specimens in Kuwait. BMC Infect Dis 13:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi; approved standard—2nd ed. CLSI document M38-A2 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camps SM, Dutilh BE, Arendrup MC, Rijs AJ, Snelders E, Huynen MA, Verweij PE, Melchers WJ. 2012. Discovery of a HapE mutation that causes azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus through whole genome sequencing and sexual crossing. PLoS One 7:e50034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williamson EC, Leeming JP, Palmer HM, Steward CG, Warnock D, Marks DI, Millar MR. 2000. Diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in bone marrow transplant recipients by polymerase chain reaction. Br J Haematol 108:132–139. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White PL, Linton CJ, Perry MD, Johnson EM, Barnes RA. 2006. The evolution and evaluation of a whole blood polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of invasive aspergillosis in hematology patients in a routine clinical setting. Clin Infect Dis 42:479–486. doi: 10.1086/499949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas PG, Maertens J, Lortholary O, Kauffman CA, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Maschmeyer G, Bille J, Dismukes WE, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Kibbler CC, et al. 2008. Revised definitions of invasive fungal diseases from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infection Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 46:1813–1821. doi: 10.1086/588660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]