Abstract

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are abnormal growths of hormone-producing cells in the pancreas. Different from the brain in the skull, the pancreas in the abdomen can be largely deformed by the body posture and the surrounding organs. In consequence, both tumor growth and pancreatic motion attribute to the tumor shape difference observable from images. As images at different time points are used to personalize the tumor growth model, the prediction accuracy may be reduced if such motion is ignored. Therefore, we incorporate the image-derived pancreatic motion to tumor growth personalization. For realistic mechanical interactions, the multiplicative growth decomposition is used with a hyperelastic constitutive law to model tumor mass effect, which allows growth modeling without compromising the mechanical accuracy. With also the FDG-PET and contrast-enhanced CT images, the functional, structural, and motion data are combined for a more patient-specific model. Experiments on synthetic and clinical data show the importance of image-derived motion on estimating physiologically plausible mechanical properties and the promising performance of our framework. From six patient data sets, the recall, precision, Dice coefficient, relative volume difference, and average surface distance are 89.8±3.5%, 85.6±7.5%, 87.4±3.6%, 9.7±7.2%, and 0.6±0.2 mm respectively.

1 Introduction

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are abnormal growths of hormone-producing cells in the pancreas [4]. They are slow growing and usually not treated until reaching a certain size threshold. Similar to most tumors, pancreatic tumor growth is associated with cell invasion and mass effect [6]. In cell invasion, tumor cells migrate as a group and penetrate to the surrounding tissues. Mass effect is the result of expansive growth which increases the tumor volume, and the outward pushing may displace the tumor cells and surrounding tissues. Mass effect also contributes to and enhances cell invasion.

In image-based macroscopic tumor growth modeling, tumor cell invasion is mostly modeled through reaction-diffusion equations [3], [7], [9], [12], [18]. The differences among these models are usually the choices between isotropic and anisotropic diffusion, Gompertz and logistic cell proliferation, or with and without considering treatment effects. Because of the highly deformable nature of the pancreas, we concentrate on mass effect and tumor mechanical properties in this paper. Most works have modeled mass effect by explicitly enforcing tumor size change or by exerting tumor-density-induced forces to a mechanical model [3], [13], [7], [18]. In [3], [13], the mass effects of the brain glioma and its surrounding edema were modeled differently based on their physiological characteristics. In [3], the volume change of the bulk tumor core was modeled as an exponential function, and a penalty method was used to enforce the volume change via homogeneous pressure. For the edema, internal stresses proportional to the local tumor cell densities were introduced, thus the tumor and its surrounding structures are displaced by tumor-density-induced forces proportional to the negative gradients of the local tumor densities. In [13], the expansive force of the bulk tumor was approximated by constant outward pressure acting on the tumor boundary, and the growth of the edema was modeled as an isotropic expansive strain. In [7], using the model at the edema of [3], the tumor-density-induced forces were applied on the entire brain glioma. The forces were converted to velocities through a linear mechanical model, which were used in the advection term in a reaction-advection-diffusion equation to displace the tumor cell densities. In [18], the tumor-density-induced forces were adopted to model the mass effect of pancreatic tumor growth using finite element methods (FEM).

Despite the promising results, these models were mostly developed for brain tumors and may be inappropriate for pancreatic tumor growths. Different from the brain in the skull, the pancreas in the abdomen can be largely deformed by the body posture and its surrounding organs [5]. Therefore, the tumor shape difference observable from images is not only driven by the tumor growth, but also the motion of the pancreas. As images at different time points are used to infer the tumor growth properties during model personalization, the prediction accuracy may be reduced if such motion is not properly considered. For the approaches which apply forces derived from tumor densities [7], [18], the tumor volume change cannot be explicitly modeled. These approaches, together with those converting the volume change into pressure [3], [13], model the tumor growth as stress-strain relation in continuum mechanics. First of all, this contradicts the nearly incompressible nature of most solid tumors, and thus the incompressibility of the mechanical model needs to be compromised. Secondly, for the mechanical models with nonlinear constitutive laws, the tumor stiffness increases with its elastic volume change regardless of the underlying physiology, and this reduces the model accuracy.

In view of these limitations, here we adopt the multiplicative growth decomposition for mass effect, which was initially introduced to study residual stresses in soft tissues [15], [11]. In this approach, the continuous deformation field of a body after growth can be decomposed into its growth and elastic parts (Fig. 1). The intermediate growth configuration can be stress-free but incompatible, which may have holes, overlaps, or other discontinuities. To maintain the continuity of the structure in reality, elastic deformation which generates residual stresses is applied to the growth deformation. With this decomposition, tumor growth can be modeled separately from the elastic part using explicit growth functions. This preserves the accuracy of the elastic response, and anisotropic mass effect can be easily incorporated. Moreover, with the relation between the growth and elastic parts, the deformation exerted by the surrounding structures on the tumor can be naturally included through displacement boundary conditions.

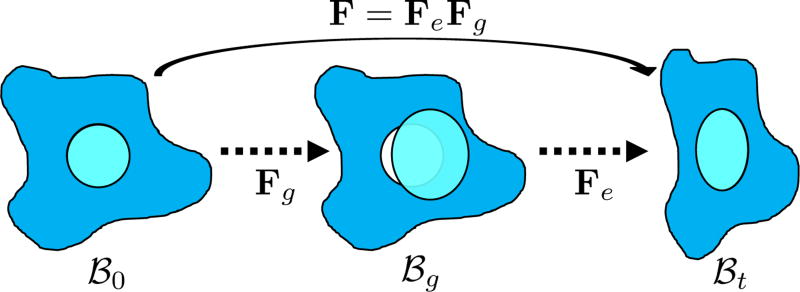

Fig. 1.

Multiplicative growth decomposition. The original configuration ℬ0 comprises the tumor (cyan) and its surrounding tissues (blue) before growth. The growth deformation gradient Fg, which grows the tumor only, leads to an intermediate incompatible configuration ℬg. With the elastic deformation gradient Fe applied, the final configuration ℬt is compatible.

In this paper, the tumor growth model accounting for both cell invasion and mass effect is personalized using medical images. The tumor cell invasion is modeled as a reaction-diffusion equation. The mass effect is modeled through multiplicative growth decomposition [11], with the growth part modeled as orthotropic stretches with logistic functions, and the elastic part modeled using a hyperelastic constitutive law [8]. The tumor growth prediction is achieved through model parameter estimation using derivative-free optimization. Following [18], 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomographic (FDG-PET) images are used to compute the proliferation rates, and contrast-enhanced computed tomographic (CT) images are used to provide the local tumor cell densities. We also incorporate the displacements derived from post-contrast CT images to account for the pancreatic motion. Experiments were performed on synthetic and clinical data to compare the differences between using different models of mass effect and between with and without imaged-derived motion.

2 Multiplicative Growth with Hyperelastic Mechanical Model

Let X be the coordinates in the original configuration (ℬ0) and x be the corresponding coordinates in the final (deformed) configuration (ℬt) (Fig. 1). To model mass growth, the deformation gradient F = ∂x/∂X, which maps the original configuration to the final configuration as dx = FdX, can be decomposed into its elastic part (Fe) and growth part (Fg) as F = FeFg [11]. Inhomogeneous growth can result in gaps or overlaps in the intermediate configuration (ℬg), and the system equation cannot be solved therein. Therefore, we need to formulate the quantities in ℬg in terms of those in the compatible configuration ℬ0 for the total-Lagrangian formulation [2].

In multiplicative growth decomposition, the elastic part is governed by the strain energy function which provides the stress-strain relation. The Green-Lagrange strain tensor and its elastic part (εe) and growth part (εg) are related as:

| (1) |

With tissue growth, the changes of mass and density need to be considered for accurate stress-strain relation. Let tm be the grown mass in ℬt, and 0V and gV be the volumes in ℬ0 and ℬg, respectively1. The densities of the grown mass with respect to different configurations are given as and , with relation (Jg = det Fg = dgV /d0V indicates the volume ratio). Therefore, the second Piola-Kirchhoff (PKII) stress tensor in ℬg is given as:

| (2) |

where Ψ is the strain energy per unit grown mass, and thus and are the strain energy per unit intermediate and original volume, respectively. Thus the PKII stress tensor in ℬ0 is given as:

| (3) |

and the corresponding fourth-order elasticity tensor is given as:

| (4) |

with the non-standard dyadic product [A⊗̄B]ijkl = [A]ik [B]jl and ℂe = ∂Se/∂εe. Note that when there is no growth (i.e. Fg = I), S = Se and ℂ = ℂe.

To model the highly deformable pancreas, the modified Saint-Venant-Kirchhoff (hyperelastic) constitutive law is used [8]:

| (5) |

where ε̄e is the isovolumetric part of εe and Je = det Fe. The first and second term of (5) account for the volumetric and isochoric elastic response, respectively, and thus λ is the bulk modulus and μ is the shear modulus.

Therefore, given Fg from a growth model, and F the existing deformation, εe can be computed by (1). Se and ℂe can then be computed using (5) and converted to S and ℂ by (3) and (4) for the total-Lagrangian formulation. The system is solved by FEM with Newton-Raphson iterations for the final geometry [2].

2.1 Orthotropic Growth

The growth deformation Fg can be modeled using explicit functions. Although tissue structure is unavailable in our data, orthotropic mass growth is adopted [11]:

| (6) |

with ϑ1, ϑ2, and ϑ3 the stretch ratios along the orthonormal vectors v1, v2, and v3, respectively. All ϑi > 0. As tumor growth slows down after a certain size as nutrients are limited, we model the stretch ratios as logistic functions:

| (7) |

with ϱi the proliferation rate, ϑi(t0) the initial stretch ratio, and ϑ̄i the maximum stretch ratio. As ϑi(t0) is relative and cannot be measured from a single image, we assume ϑi(t0 = 0) = 1 at the first measurement time point. The maximum stretch ratio is computed from the maximum allowable tumor size to the initial tumor size. In [10], the largest pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor size without metastasis is 5 cm.

2.2 Image-Derived Pancreatic Motion

The tumor shape difference observable from images is caused by both the tumor growth and the deformation exerted by the surrounding structures. To incorporate such deformation for more realistic model personalization, the region of interest (ROI) around the tumor which covers the salient features of the pancreas is extracted from every post-contrast CT image. ROIs of consecutive time points are registered using deformable image registration with mutual information to provide the displacements of the salient features [14] (Fig. 2(a)). The displacements are enforced as boundary conditions to deform the grown tumor through the hyperelastic constitutive law, and this allows more accurate comparison with the measurements during model personalization. To avoid interfering the tumor growth, a 3D FEM mesh is constructed from the ROI with three zones: the tumor, its surroundings for growth, and the outer zone (Fig. 2(b)). The image-derived displacements are only applied at the outer zone.

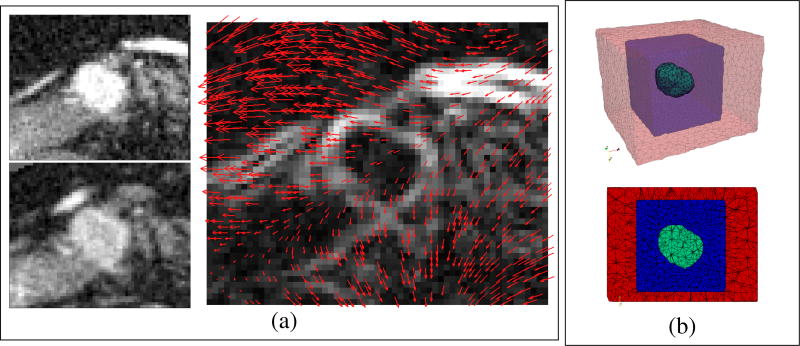

Fig. 2.

(a) Image-derived pancreatic motion. Left: the ROIs of the post-contrast CT images at the earlier (top) and later (bottom) time points. Right: the 3D deformation field from the earlier to the later time point obtained by deformable image registration, overlapping with the gradient magnitude image at the earlier time point. Only the displacements of the salient features are used. (b) The 3D linear FEM mesh and its middle slice. The green zone is the segmented tumor, which can freely grow into the blue zone. The red zone is for enforcing image-derived displacements.

3 Tumor Cell Invasion by Reaction-Diffusion Equation

With the mass effect modeled by multiplicative growth decomposition and image-derived motion, the tumor cell invasion is modeled by a reaction-diffusion equation [18]:

| (8) |

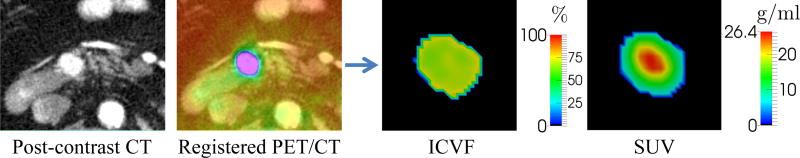

where the first and second term account for the tumor invasion and logistic cell proliferation, respectively. c ∈ [0, 1] is the intracellular volume fraction (ICVF) which is equivalent to the number of tumor cells (N) divided by the carrying capacity (K) as the number of cells is proportional to the space they occupy. ICVF can be computed from contrast-enhanced CT images to provide the initial conditions of (8) and the measurements for model personalization (Fig. 3). D is the anisotropic diffusion tensor, which is a diagonal matrix with components Dx, Dy, and Dz regardless of the tissue structure, characterizing the invasive property. ρ is the proliferation rate, which can be computed from FDG-PET images for better subject-specificity.

Fig. 3.

ICVF and SUV computed from contrast-enhanced CT and FDG-PET images.

3.1 Computing Intracellular Volume Fractions from CT Images

An intravenously-administered iodine-based contrast agent is used to produce contrast-enhanced CT images. The contrast agent causes greater absorption and scattering of x-ray in the target tissue, thereby producing contrast enhancement [1]. As the enhancement is proportional to the extracellular space, ICVF (c) of the tumor is given as [18]:

| (9) |

where HUpost_tumor, HUpre_tumor, HUpost_blood, and HUpre_blood are the Hounsfield units of the post- and pre-contrast CT images at the segmented tumor and blood pool (aorta), respectively. H ct is the hematocrit which can be obtained from blood samples, thus the ICVF of the tumor is computed using the ICVF of blood (H ct) as a reference.

3.2 Computing Proliferation Rates from FDG-PET Images

The energy flow rate (B) provided to tissue can be consumed to maintain existing cells or create new cells [17], which can be represented as:

| (10) |

with Bc the metabolic rate of a cell and Ec the metabolic energy to create a cell. Assuming logistic growth, we substitute , and (10) becomes:

| (11) |

where SUV is the standardized uptake value computed from FDG-PET images, which indicates metabolic activity. α > 0 is an unknown scalar to be estimated, and β ≈ 0.02 day−1 [17]. B = αEcK SUV indicates that the energy flow rate (B) is proportional to SUV. Therefore, the proliferation rate (ρ) can be approximated from FDG-PET and CT images (Fig. 3). With (8), (9), (11), physiologically meaningful quantities can be computed from images and combined to produce a more patient-specific model.

4 Gradient-Free Model Personalization

The model personalization is achieved by parameter estimation. The simulation with model parameters θ is rasterized into an ICVF image by using the CT image at the same time point as a reference, and then the following objective function is computed:

| (12) |

where TPV is the true positive volume, the overlapping volume between the simulated tumor volume (Vs) and the measured (segmented) tumor volume (Vm). c̄ and c(θ) are the respective measured and simulated ICVF within TPV. Therefore, the objective function accounts for both the ICVF root mean-squared error and volume difference.

As the gradient of the objective function is difficult to derive analytically, we adopted the gradient-free direct search method SUBPLEX (SUBspace-searching simPLEX) for parameter estimation [16], which is a generalization of the Nelder-Mead simplex method (NMS). A simplex in n-dimensional space is a convex hull of n + 1 points, such as a tetrahedron in 3D. In NMS, a simplex moves through the objective function space, changing size and shape, and shrinking near the minimum. SUBPLEX improves NMS by decomposing the searching space into subspaces for better computational efficiency, so that the model personalization can be performed with intact model nonlinearity.

Not all parameters are estimated in our current framework. In (11), with known c and SUV from images, ρ is a plane function of α and β, and any α and β on the same contour contribute to the same proliferation rate. Therefore, we fix β = 0.02 day−1 from [17]. For the mechanical parameters in (5), λ in all regions are set to 5 kPa for tissue incompressibility. As a result, the parameters to be estimated are θ = {Dx, Dy, Dz, αϱ, x, ϱy, ϱz, μnormal, μtumor}, with μtumor and μnormal the shear modulus of the tumor and its surrounding tissues, respectively.

5 Experiments

Three frameworks were tested on synthetic and clinical data to study the differences between with and without image-derived motion, and between using multiplicative growth decomposition and tumor-density-induced forces:

-

–

MG-IM: the proposed framework with multiplicative growth decomposition (MG) and image-derived motion (IM).

-

–

MG: using multiplicative growth decomposition without image-derived motion.

-

–

F-IM: using tumor-density-induced forces (F), fb = −γ∇c, for the mass effect, with γ a scalar to be estimated [18]. Image-derived motion was used.

5.1 Experimental Setups

Measurements at three time points were used in each experiment, which comprise both FDG-PET and contrast-enhanced CT images. From each post-contrast CT image, the tumor was segmented by a level set algorithm with region competition [19]. A ROI of the post-contrast CT image around the tumor was selected manually, which covers the salient features of the pancreas (Fig. 2(a)). ROIs of consecutive time points were registered to provide image-derived displacements (Fig. 2(a)), which were enforced to the outer region of the FEM mesh (Fig. 2(b), Section 2.2). ICVF and SUV were also computed from the contrast-enhanced CT and FDG-PET images for the reaction-diffusion equation (Section 3.1 and 3.2).

In each experiment, simulation was performed on the FEM mesh at the first time point, with the ICVF, SUV, and image-derived motion providing the initial conditions, proliferation rates, and displacement boundary conditions, respectively. This simulation was rasterized and compared with the measured ICVF and tumor volume at the second time point to evaluate the objective function for parameter estimation. Prediction was performed by simulating the tumor growth using the personalized parameters, with the mesh, ICVF, SUV, and image-derived motion at the second time point. The prediction performance was evaluated using the measurements at the third time point, and was represented as recall, precision, Dice coefficient, relative volume difference (RVD), average surface distance (ASD), and ICVF root mean-squared error (RMSE) (Dice = 2 × TPV/(Vs + Vm) and RVD = |Vs − Vm|/Vm).

5.2 Synthetic Data

Using the FEM mesh and image-derived information of a patient at the first time point (Day 0, Fig. 4(a)), the second time point (Day 300) was simulated with the ground-truth model parameters using the proposed model (Table 1). This FEM simulation was rasterized into an ICVF image to provide the measurement input to the experiments. The estimated parameters were then used to predict the tumor growth at the third time point (Day 600) and compared with the simulated ground truth. Ground truths with ϱx = 1, 2, 3, 4 × 10−4 day−1 were simulated to study the prediction performance at different multiplicative growth rates. Identical settings were used in all tests.

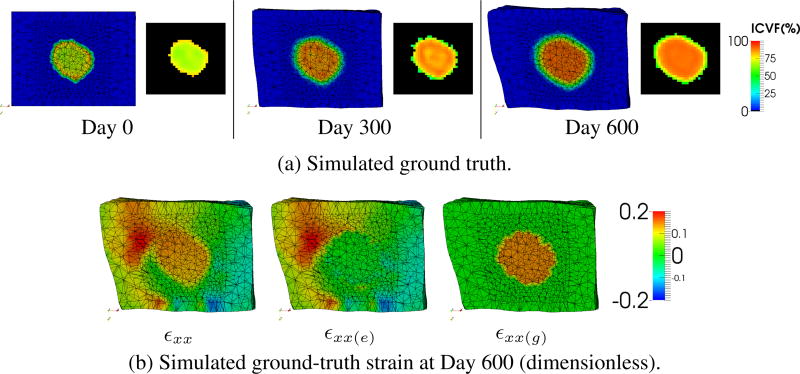

Fig. 4.

Synthetic data (ϱx = 3 × 10−4 day−1). (a) The simulated ground truth at three time points. Left: FEM simulation. Right: rasterized image. (b) The ground-truth strain along the x-axis (εxx) and its elastic (∊xx(e)) and growth (εxx(g)) parts at Day 600.

Table 1.

Synthetic data. Estimated parameters and prediction performances. Simulations with ϱx = 1, 2, 3, 4 × 10− day−1 were used to study the performances at different growth rates.

| Dx,Dy,Dz(mm2/day,10−3) | α(mm3/g/day) | ϱy,ϱz (day−1,10−4) | μnormal,μtumor(kPa) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ground truth | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| MG-IM | 1.0±0.0 | 0.5±0.0 | 0.5±0.0 | 0.6±0.0 | 1.9±0.1 | 1.0±0.0 | 1.0±0.0 | 5.0±0.1 |

| MG | 1.3±0.1 | 0.5±0.1 | 0.2±0.2 | 0.6±0.0 | 1.0±1.0 | 0.4±0.1 | 0.6±0.2 | 0.6±0.1 |

| F-IM | 0.9±0.2 | 0.5±0.2 | 0.3±0.2 | 0.6±0.1 | - | - | 1.1±0.1 | 5.2±0.4 |

| Ground truth | ϱx | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | Recall(%) | Precision(%) | Dice(%) | RVD(%) | ASD(mm) | RMSE(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG-IM | ϱx | 0.9 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 3.9 | MG-IM | 99.4±0.2 | 99.7±0.1 | 99.6±0.2 | 0.3±0.2 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.2±0.1 |

| MG | ϱx | 0.6 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | MG | 89.2±2.0 | 91.5±1.8 | 90.3±0.6 | 3.8±2.1 | 0.6±0.1 | 6.9±0.6 |

| F-IM | γ(kPa) | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | F-IM | 92.4±1.6 | 98.2±3.1 | 95.2±1.1 | 6.1±3.8 | 0.3±0.2 | 3.6±1.5 |

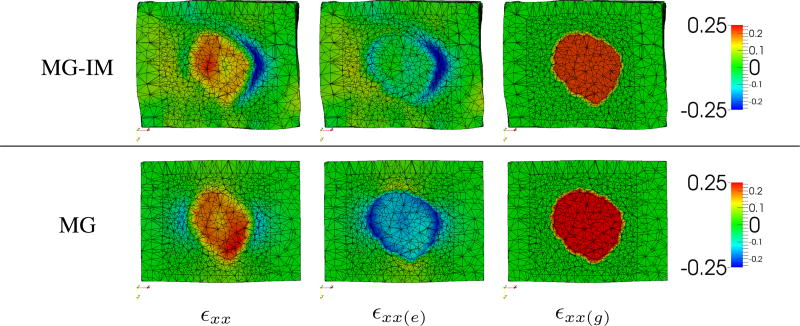

Fig. 4(b) shows the strain of the simulated ground truth with ϱx = 3 × 10−4 day−1. Only the strain along the x-axis is shown due to space limitation. The growth strain (εxx(g)) of the normal tissues is zero as we modeled no growth in that region. As the tumor is five times as stiff as the surrounding tissues (Table 1), the tumor region has almost no elastic strain (εxx(e)) with the enforced image-derived displacements. The final strain (εxx) comprises the features of both the growth and elastic parts. These demonstrate the characteristics of the multiplicative growth decomposition.

Table 1 shows the estimated parameters and the prediction performances. As discretization noise and information loss were introduced during image rasterization, the parameter estimation was nontrivial. The proposed MG-IM framework has the best overall performance as it used the same model as the ground truth with the image-derived motion. The MG and F-IM frameworks could not precisely estimate the diffusion parameters (Di), but the estimated degrees of anisotropy are similar to those of the ground truth. Without the image-derived motion, the MG framework underestimated the shear moduli (μnormal, μtumor), and thus the multiplicative growth rates (ϱi) could not be accurately estimated. On the other hand, although the ground-truth values of the force scalar (γ) of the F-IM framework are unknown, they mostly increase with the increase of ϱx because of the better estimation of μnormal and μtumor. The F-IM framework performs better than the MG framework in general.

5.3 Clinical Data

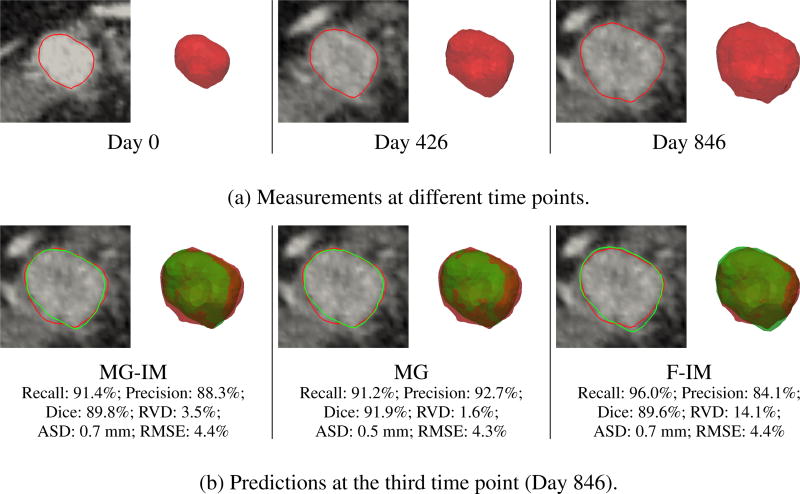

Images from six patients (five males and one female) with diagnosed pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors were studied. The average age and weight of the patients at the first time point were 46.5±14.0 years and 89.6±17.7 kg, respectively. Each data set has three time points of images spanning three to four years, and the pixel sizes are less than 0.94 × 0.94 × 1:00 mm3 for CT and 4.25 × 4.25 × 3.27 mm3 for PET. Fig. 5(a) shows an example of the measurements. Identical settings were used in all tests.

Fig. 5.

Clinical data. (a) The segmented tumor volumes at different time points, and the corresponding contours overlapping with the post-contrast CT images. (b) The prediction results at the third time point, with red and green represent measurements and predictions, respectively.

Table 2 shows the estimated parameters and prediction performances. The MG-IM framework has similarly good prediction performance with the MG framework, while that of the F-IM framework is the worst. The diffusion parameters (Di) of the MG-IM and MG frameworks are close to zero, which means that the tumor size changes are mainly governed by the mass effect. Similar to the synthetic data, the μtumor estimated by the MG framework are relatively small, which on average even smaller than μnormal. As this is physiologically implausible for solid tumors, this shows the importance of using image-derived motion on estimating plausible mechanical parameters.

Table 2.

Clinical data. Estimated parameters and prediction performances.

| Dx,Dy,Dz(mm2/day,10−3) | α(mm3/g/day) | ϱx,ϱy,ϱz(day−1,10−4) | μnormal,μtumor(kPa) | γ(kPa) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG-IM | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.4±0.4 | 4.7±3.2 | 4.2±3.2 | 4.6±4.7 | 0.6±0.3 | 40.4±10.1 | - |

| MG | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.5±0.3 | 8.2±8.6 | 6.9±5.1 | 6.2±7.3 | 3.5±1.9 | 1.6±1.3 | - |

| F-IM | 0.0±0.1 | 0.1±0.2 | 0.3±0.8 | 0.5±0.5 | - | - | - | 0.8±0.9 | 44.3±13.1 | 2.4±3.8 |

| Recall(%) | Precision(%) | Dice(%) | RVD(%) | ASD(mm) | RMSE(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG-IM | 89.8±3.5 | 85.6±7.5 | 87.4±3.6 | 9.7±7.2 | 0.6±0.2 | 9.6±5.0 |

| MG | 90.1±5.2 | 87.9±6.6 | 88.7±2.9 | 9.2±8.6 | 0.5±0.2 | 9.2±5.4 |

| F-IM | 84.1±9.1 | 91.6±6.0 | 87.2±3.7 | 14.3±7.4 | 0.5±0.2 | 11.4±5.1 |

Fig. 6 compares the predicted strains between the MG-IM and MG frameworks. As the image-derived motion was relatively small in this example, the elastic strains (εxx(e)) caused by the tumor growth is more obvious. The negative elastic strains around the tumor indicate the outward pushing of the tumor and the resistance of its surrounding tissues. These negative elastic strains reduce the final strains (εxx) in the tumor region. As mentioned, as the MG framework has estimated μtumor smaller than μnormal, the tumor is more deformable than its surrounding tissues. In consequence, the tumor growth generates elastic contraction in the tumor region, leading to a final strain which is similar to that of the MG-IM framework.

Fig. 6.

Clinical data. Predicted strains (dimensionless) along the x-axis (εxx) and their elastic (εxx(e)) and growth (εxx(g)) parts at the third time point. MG-IM: μnormal = 0.4 kPa, μtumor = 26.5 kPa. MG: μnormal = 3.9 kPa, μtumor = 1.1 kPa.

Fig. 5(b) compares the predictions with the measurements. For this data set, all frameworks have good prediction performances. Despite the implausible mechanical properties estimated by the MG framework, it performs slightly better than the MGIM framework. Consistent with Table 2, the F-IM framework has the worst but still promising prediction performance.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we have presented a pancreatic tumor growth prediction framework with multiplicative growth decomposition and image-derived pancreatic motion. By combining the multiplicative decomposition with a hyperelastic mechanical model, the tumor growth can be modeled as explicit functions without compromising the accuracy of the elastic response. With also the contrast-enhanced CT and FDG-PET images, the structural, functional, and motion information can be combined for more patient-specific models. Experiments on synthetic data show that image-derived motion is important for estimating physiologically plausible mechanical properties. Experiments on clinical data show that the framework can achieve promising prediction performance.

Footnotes

The left superscript and subscript represent the measuring time and reference configuration.

References

- 1.Bae KT. Intravenous contrast medium administration and scan timing at CT: considerations and approaches. Radiology. 2010;256(1):32–61. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10090908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bathe KJ. Finite Element Procedures. Prentice Hall. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clatz O, Sermesant M, Bondiau PY, Delingette H, Warfield SK, Malandain G, Ayache N. Realistic simulation of the 3D growth of brain tumors in MR images coupling diffusion with biomechanical deformation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2005;24(10):1334–1346. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.857217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehehalt F, Saeger HD, Schmidt CM, Grützmann R. Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas. The Oncologist. 2009;14(5):456–467. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng M, Balter JM, Normolle D, Adusumilli S, Cao Y, Chenevert TL, Ben-Josef E. Characterization of pancreatic tumor motion using cine MRI: surrogates for tumor position should be used with caution. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(3):884–891. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedl P, Locker J, Sahai E, Segall JE. Classifying collective cancer cell invasion. Nature Cell Biology. 2012;14(8):777–783. doi: 10.1038/ncb2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogea C, Davatzikos C, Biros G. An image-driven parameter estimation problem for a reaction-diffusion glioma growth model with mass effects. Journal of Mathematical Biology. 2008;56(6):793–825. doi: 10.1007/s00285-007-0139-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holzapfel GA. Nonlinear Solid Mechanics: A Continuum Approach for Engineering. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konukoglu E, Clatz O, Menze BH, Stieltjes B, Weber MA, Mandonnet E, Delingette H, Ayache N. Image guided personalization of reaction-diffusion type tumor growth models using modified anisotropic eikonal equations. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2010;29(1):77–95. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2026413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Libutti SK, Choyke PL, Bartlett DL, Vargas H, Walther M, Lubensky I, Glenn G, Linehan WM, Alexander HR. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors associated with von Hippel Lindau disease: diagnostic and management recommendations. Surgery. 1998;124(6):1153–1159. doi: 10.1067/msy.1998.91823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lubarda VA, Hoger A. On the mechanics of solids with a growing mass. International Journal of Solids and Structures. 2002;39(18):4627–4664. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menze BH, Van Leemput K, Honkela A, Konukoglu E, Weber MA, Ayache N, Golland P. A generative approach for image-based modeling of tumor growth. In: Székely G, Hahn HK, editors. IPMI 2011. LNCS. Vol. 6801. Springer Berlin Heidelberg: 2011. pp. 735–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohamed A, Davatzikos C. Finite element modeling of brain tumor mass-effect from 3D medical images. In: Duncan J, Gerig G, editors. MICCAI 2005, Part I. LNCS. Vol. 3749. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2005. pp. 400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pluim JPW, Maintz JBA, Viergever MA. Mutual-information-based registration of medical images: a survey. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2003;22(8):986–1004. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.815867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez EK, Hoger A, McCulloch AD. Stress-dependent finite growth in soft elastic tissues. Journal of Biomechanics. 1994;27(4):455–467. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowan T. Ph.D. thesis. University of Texas at Austin; 1990. Functional Stability Analysis of Numerical Algorithms. [Google Scholar]

- 17.West GB, Brown JH, Enquist BJ. A general model for ontogenetic growth. Nature. 2001;413(6856):628–631. doi: 10.1038/35098076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong KCL, Summers RM, Kebebew E, Yao J. Tumor growth prediction with hyperelastic biomechanical model, physiological data fusion, and nonlinear optimization. In: Golland P, Hata N, Barillot C, Hornegger J, Howe R, editors. MICCAI 2014, Part II. LNCS. Vol. 8674. Springer International Publishing; 2014. pp. 25–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, Smith RG, Ho S, Gee JC, Gerig G. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. NeuroImage. 2006;31(3):1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]