ABSTRACT

Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates (n = 110) from health care centers in central Indiana (from 2010 to 2013) were tested for susceptibility to combinations of avibactam (4 μg/ml) with ceftazidime, ceftaroline, or aztreonam. MIC50/MIC90 values were 1/2 μg/ml (ceftazidime-avibactam), 0.5/2 μg/ml (ceftaroline-avibactam), and 0.25/0.5 μg/ml (aztreonam-avibactam.) A β-lactam MIC of 8 μg/ml was reported for the three combinations against one Escherichia coli isolate with an unusual TIPY insertion following Tyr344 in penicillin-binding protein 3 (PBP 3) as the result of gene duplication.

KEYWORDS: carbapenem-resistant, CRE, avibactam, ceftazidime, ceftaroline, aztreonam, carbapenemase, resistance, PBP 3

TEXT

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) have been designated one of the most urgent antibiotic resistance threats by multiple global health organizations (1, 2). Carbapenemase-producing CRE are most worrisome, due primarily to plasmid-encoded KPC, SME, and OXA families with serines at their active sites and the NDM and VIM metallo-β-lactamase (MBL) families (3). The recently approved β-lactamase inhibitor combination ceftazidime-avibactam provides the potential for treating many CRE infections caused by pathogens with serine carbapenemases that are inhibited by avibactam (4). Although avibactam does not inhibit MBLs, its combination with aztreonam protects the monobactam against hydrolysis by serine enzymes, while aztreonam remains functionally active due to its stability to MBLs (5). In addition, a ceftaroline-avibactam combination potentially could allow for the treatment of mixed infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and CRE (6). In this study, the three avibactam combinations were tested against 110 recent multidrug-resistant CRE isolates with well-characterized β-lactamase profiles (7) to determine whether there was a reservoir of contemporary isolates resistant to any of the combinations.

Avibactam was furnished by Allergan; all other antibacterial agents were obtained from the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention (USP, Rockville, MD). Consecutive carbapenemase-producing CRE isolates from 172 discrete patients (from 2010 to 2013) were provided by a central clinical microbiology laboratory that serviced 14 Indiana health care centers and two large urban hospitals (5, 7). After a Vitek 2 system identified carbapenem-resistant isolates, those isolates with positive results in the modified Hodge test (MHT) (8) were tested using the Carba NP test (9). Two SME-producing Serratia marcescens isolates from a second laboratory (2011) were included. Based on bacterial species, susceptibility profiles, and β-lactamase composition, 110 representative isolates were selected (Table 1). MICs were determined for the avibactam combinations and comparator agents using broth microdilution according to CLSI guidelines (10) on at least two separate days.

TABLE 1.

CRE isolates used for susceptibility testing with β-lactamase identities confirmed through molecular and biochemical testing

| Organism | Carbapenemase(s)a | No. of isolates | Other plasmid-encoded β-lactamasesb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterobacter cloacae | KPC-3, VIM-1 | 1 | TEM |

| 1 | TEM, SHV | ||

| 1 | TEM, OXA, SHV | ||

| Escherichia coli | KPC-2 | 1c | TEM-1 |

| KPC-3 | 1 | TEM, OXA, CTX-M-15 | |

| 3 | TEM, OXA, SHV, CTX-M-15 | ||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | KPC-2 | 1 | TEM |

| 10 | TEM, SHV | ||

| 4 | TEM, OXA, SHV | ||

| KPC-3 | 20 | TEM | |

| 1 | OXA | ||

| 3 | SHV | ||

| 2 | TEM, OXA | ||

| 32 | TEM, SHV | ||

| 2 | SHV, CTX-M-15 | ||

| 17 | TEM, OXA, SHV | ||

| 2 | TEM, SHV, CTX-M-15 | ||

| 1 | TEM, OXA, SHV, CTX-M-15 | ||

| KPC-3, NDM-1 | 1 | TEM, OXA, SHV | |

| Serratia marcescens | KPC-3 | 1 | TEM |

| 2 | TEM, SHV | ||

| SME-1 | 3 | TEM, SHV |

Carbapenemase production was initially detected using a modified Hodge test (8) and later confirmed by the Carba NP test (9). All carbapenemase genes were detected by PCR, followed by sequencing of the full gene.

Additional β-lactamases were detected by PCR or WGS, with full or partial sequencing of individual genes. Most TEM, OXA, and SHV enzymes were identified only according to enzyme families.

Isolate EC-1 also contained mutations in PBP 2 (A543T) and PBP 3 (insertion of TIPY following Y334, and A417V).

Plasmid DNA from all isolates and genomic DNA from Serratia marcescens were purified using the GenElute bacterial genomic DNA kit (Sigma Life Science) and screened for blaSME (11) by PCR. Plasmidic DNA was screened for blaCTX-M, blaOXA, blaSHV, blaTEM, blaKPC, blaIMP, blaNDM, and blaVIM with published primer sets (12–15); PCR products were sequenced using the BigDye 3.1 kit (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed by BLAST. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was performed on 29 isolates selected for distinguishing resistance phenotypes to identify additional chromosomal β-lactamase genes. Individual libraries of prokaryotic genomic material were PCR amplified using the NEXTFlex rapid DNA-Seq kit (Bio Scientific Corporation, Austin, TX, USA) and were pooled and submitted for sequencing using an Illumina NextSeq 500/550 Mid output v2 kit (150 cycles) (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Bioinformatics included microbial genome assembly and prokaryotic genome annotation. The reads were mapped to reference genomes using Breseq (v0.27.1) (16); β-lactamase and penicillin-binding protein (PBP) gene sequences were compared to standards in the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/). The modeling of the apo Escherichia coli PBP 3 structure was based on the publicly available structure (PDB:4BJP) (17). The effect of amino acid substitutions was studied using PyMol (Schroedinger, New York, NY).

All isolates produced a serine carbapenemase, either KPC-3 (91/110 [82.7%]), KPC-2 (16/110 [14.5%]), or SME-1 (3/110 [2.7%]) (Table 1). Initially, nine isolates coproduced KPC-3 and an MBL (VIM-1, n = 8; NDM-1, n = 1), but five of these lost blaVIM genes during the study. Nonsusceptibility was 98 to 100% for ceftazidime, ceftaroline, aztreonam, piperacillin-tazobactam, and meropenem with the full isolate collection and 100% for MBL- and KPC-producing K. pneumoniae isolates (Table 2). The addition of avibactam (4 μg/ml) to ceftazidime, ceftaroline, or aztreonam resulted in MIC50/MIC90 values for the respective combinations of 1/2 μg/ml, 0.5/2 μg/ml, or 0.25/0.5 μg/ml (Table 2). Only the four MBL-producing isolates had MICs for the cephalosporin combinations >8 μg/ml (range, 64 to >128 μg/ml). Aztreonam-avibactam had MICs of 0.12 to 0.25 μg/ml against the four isolates that coproduced KPC-3 and the MBLs VIM-1 or NDM-1, together with one to three additional serine β-lactamases. The highest MIC for all avibactam combinations against non-MBL-producing isolates was 8 μg/ml for E. coli strain EC-1.

TABLE 2.

MIC distributions of ceftazidime, ceftaroline, and aztreonam alone and in avibactam combinations compared with those of piperacillin-tazobactam and meropenem when tested against 110 CRE isolates

| Agenta | MIC (μg/ml) |

% susceptibleb | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | >16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | >128 | 50% | 90% | ||

| Ceftazidime | 1c | 1c | 8 | 34 | 66 | >128 | >128 | 1.8 | ||||||||

| Ceftazidime-avibactam | 1 | 1 | 12 | 46 | 43 | 2 | 1 | 4d | 1 | 2 | 96.4 | |||||

| Ceftaroline | 1 | 1 | 9 | 99 | >128 | >128 | 0 | |||||||||

| Ceftaroline-avibactam | 5 | 20 | 53 | 16 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1d | 2d | 1d | 0.5 | 2 | NAe | |||

| Aztreonam | 1 | 2 | 4 | 81 | 22 | 64 | 128 | 0 | ||||||||

| Aztreonam-avibactam | 36f | 48g | 21 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | NA | |||||||

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 1c | 1c | 108 | >128 | >128 | 1.8 | ||||||||||

| Meropenem | 1 | 3 | 16 | 90 | >16 | >16 | 0 | |||||||||

Avibactam and tazobactam were tested using a fixed 4 μg/ml concentration in the medium.

CLSI breakpoints were used (8) except for ceftazidime-avibactam, for which FDA breakpoints were used. No breakpoints were assumed for ceftaroline-avibactam and aztreonam-avibactam.

S. marcescens-producing SME-1.

MBL-producing isolate.

Not applicable. No breakpoints have been established.

Includes one VIM-1-producing E. cloacae isolate and one NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae isolate.

Includes two VIM-1-producing E. cloacae isolates.

WGS of E. coli strain EC-1 showed the blaKPC-2 and blaTEM-1 genes previously identified by PCR, in addition to mutations in PBP 2 and PBP 3. A point mutation in PBP 2 resulted in the amino acid substitution A543T, distant from the active site. Cephalosporins (18, 19), aztreonam (20), and avibactam (19) exhibit weak binding to E. coli PBP 2, which has a high affinity for carbapenems (21). It is unlikely that this mutation would result in 8- to 32-fold elevations in MICs for each combination. Noninvolvement of PBP 2 was suggested by meropenem susceptibility testing, in which the meropenem MIC against EC-1 decreased from 8 to ≤0.06 μg/ml in the presence of avibactam (our unpublished data). This was the same meropenem MIC against a non-KPC-producing E. coli, consistent with the hypothesis that the PBP 2 mutation did not affect the inhibitory activity of avibactam.

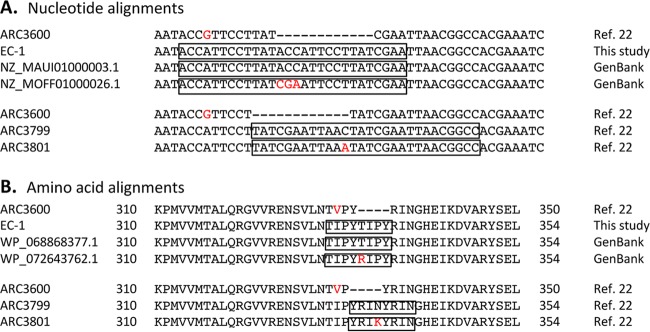

It is most likely that the elevated MICs in strain EC-1 are due to the insertion sequence in PBP 3, the primary killing target for ceftazidime, ceftaroline, and aztreonam (18–20), representing a common link among the three β-lactams. As seen in Fig. 1A, the insertion for EC-1 is the result of a perfect gene duplication leading to a four-amino-acid insertion of TIPY into PBP 3, following amino acid Tyr344 (Fig. 1B). According to the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/), PBP 3 from E. coli EC-1 had 99% identity to two unpublished sequences for the E. coli peptidoglycan glycosyltransferase FtsI, or PBP 3 (accession numbers WP_068868377.1 and WP_072643762.1). WP_068868377.1 included the identical TIPY insertion sequence, but differed at position 417 (Ala417Val). In WP_072643762.1, the only difference was in the first amino acid in the insertion sequence, namely, RIPY rather than TIPY (Fig. 1B), with a consistent Val417. Note that the TIPY insertion in EC-1 overlapped the insertion sequences described by Alm et al. as aligned in Fig. 1B (22). In that study, a similarly located YRIK insertion resulted in increases in MICs of 32-fold for aztreonam and 4- to 8-fold for ceftazidime and ceftaroline when the encoding gene was inserted into a wild-type E. coli (22). Thus, it is likely that the variant PBP 3 in EC-1 is responsible for the similarly elevated β-lactam MICs.

FIG 1.

Alignment of amino acid and nucleotide sequences associated with insertion sequences in PBP 3 (FtsI). The alignments of insertion sequences are boxed, together with their duplicated sequences, compared with the sequence of wild-type E. coli ARC3600 PBP 3 (22). Amino acids or nucleotides highlighted in red represent nonconserved sites in the alignments shown. (A) Proposed alignment of nucleotide sequences of E. coli PBP 3 variants with insertion sequences encoding the T(R)IPY insertions. The alignments shown are those proposed in this study for E. coli EC-1 PBP 3, as well as for two PBP 3 sequences from E. coli strains annotated in GenBank with similar or identical insertions. Note that the amino acid sequences WP_072643762.1 and WP_068868377.1 in panel B are aligned with nucleotide sequences NZ_MOFF01000026.1 and NZ_MAUI01000003.1, respectively. Similar gene duplications overlapping the same site are aligned according to the original publication for PBP 3 insertions from E. coli 3799 and 3801 (22). (B) Alignment of amino acid sequences of known E. coli PBP 3 variants with insertion sequences compared with the sequence of a wild-type PBP 3 from E. coli ARC3600 (22). Proposed alignments in boxes are shown for PBP 3 from EC-1 and two sequences with 99% full sequence identity in GenBank in comparison to the reference ARC3600 sequence (22). Overlapping 4-amino-acid insertion sequences for two PBP 3 sequences described in reference 22 are also shown in comparison to E. coli ARC3600.

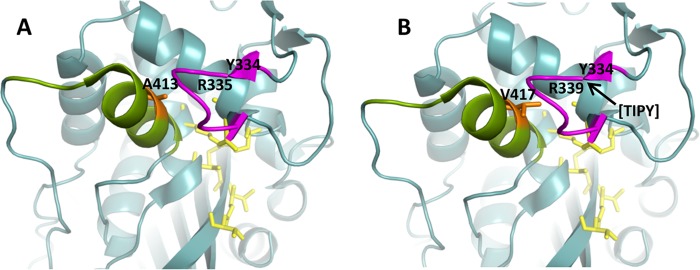

As seen in Fig. 2B, the location of the TIPY insertion in PBP 3 lies away from the transpeptidase active site, where there would be immediate contact with the β-lactam binding pocket (17, 22). However, it is in a loop adjacent to the active site and could affect the entry of a cephalosporin or monobactam (17). The A417V mutation, corresponding to A413 in wild-type PBP 3 (Fig. 2A), lies in a loop of amino acids numbered 402 to 420 that is conserved across classes of PBPs (17) and lies opposite the active site. Thus, the bulkier valine with an additional methyl group protruding toward the active site may provide steric hindrance for substrate binding.

FIG 2.

Molecular modeling of the E. coli PBP 3 native enzyme and the PBP 3 variant with amino acid substitutions based on the structure described by Sauvage et al. (17). Active site residues are shown in yellow. The loop containing the amino acid insertion is shown in magenta. The conserved loop of amino acids 402 to 420 is shown in green. The amino acid at position 413 in the native enzyme (417 in the mutant enzyme) is in orange. (A) Apo enzyme, based on reference 24. (B) PBP 3 from E. coli EC-1 with the location of the beginning of the TIPY insertion noted by an arrow at position R335 and the substitution of valine for alanine at position 413 (native enzyme) or 417 (PBP 3 variant) shown in orange.

Overall, the three avibactam combinations offer the potential to treat CRE, especially KPC-producing isolates, with the possibility that aztreonam-avibactam could be used to treat MBL-producing infections. A combination of aztreonam with ceftazidime-avibactam was recently used successfully to treat a patient infected with an NDM-1-producing pathogen (23). However, the clinical use of ceftazidime-avibactam has been linked to the emergence of resistance due to mutations in the KPC-3 Ω loop in isolates that regained susceptibility to meropenem (24). Although PBP insertions have not yet been reported to cause pathogens to become clinically resistant to ceftazidime-avibactam, their role in relation to the future utility of these combinations will need to be monitored.

Accession numbers.

GenBank accession numbers are KY629659 for PBP 2 and KY629658 for PBP 3 (FtsI).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the contributions of Sharifah Altalhi, Jessica Carpenter, and previous biotechnology students for establishing the groundwork for the β-lactamase characterization of the clinical isolates. We thank James Ford for conducting whole-genome sequencing and especially Douglas Rusch and Erika Dsouza for leading us in the analysis of the genomic data.

The authors acknowledge the support of Allergan to conduct this study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doi Y, Paterson DL. 2015. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Sem Respir Crit Care Med 36:74–84. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1544208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez F, El Chakhtoura NG, Papp-Wallace KM, Wilson BM, Bonomo RA. 2016. Treatment options for infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: can we apply “precision medicine” to antimicrobial chemotherapy? Expert Opin Pharmacother 17:761–781. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2016.1145658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li H, Estabrook M, Jacoby GA, Nichols WW, Testa RT, Bush K. 2015. In vitro susceptibility of characterized β-lactamase-producing strains tested with avibactam combinations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1789–1793. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04191-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sader HS, Flamm RK, Jones RN. 2013. Antimicrobial activity of ceftaroline-avibactam tested against clinical isolates collected from U.S. medical centers in 2010-2011. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1982–1988. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02436-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Lin X, Bush K. 2016. In vitro susceptibility of β-lactamase-producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) to eravacycline. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 69:600–604. doi: 10.1038/ja.2016.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CLSI. 2016. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 26th ed. CLSI supplement M100S CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordmann P, Poirel L, Dortet L. 2012. Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1503–1507. doi: 10.3201/eid1809.120355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CLSI. 2013. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard—9th ed. M07-A9 CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bush K, Pannell M, Lock JL, Queenan AM, Jorgensen JH, Lee RM, Lewis JS, Jarrett D. 2012. Detection systems for carbapenemase gene identification should include the SME serine carbapenemase. Int J Antimicrob Agents 41:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yigit H, Queenan AM, Anderson GJ, Domenech-Sanchez A, Biddle JW, Steward CD, Alberti S, Bush K, Tenover FC. 2001. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:1151–1161. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1151-1161.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lolans K, Queenan AM, Bush K, Sahud A, Quinn JP. 2005. First nosocomial outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing an integron-borne metallo-beta-lactamase (VIM-2) in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:3538–3540. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3538-3540.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sidjabat H, Paterson D, Adams-Haduch J, Ewan L, Pasculle A, Muto C, Tian G, Doi Y. 2009. Molecular epidemiology of CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli isolates at a tertiary medical center in western Pennsylvania. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4733–4739. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00533-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poirel L, Walsh TR, Cuvillier V, Nordmann P. 2011. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 70:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deatherage DE, Barrick JE. 2014. Identification of mutations in laboratory-evolved microbes from next-generation sequencing data using breseq. Methods Mol Biol 1151:165–188. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0554-6_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sauvage E, Derouaux A, Fraipont C, Joris M, Herman R, Rocaboy M, Schloesser M, Dumas J, Kerff F, Nguyen-Disteche M, Charlier P. 2014. Crystal structure of penicillin-binding protein 3 (PBP3) from Escherichia coli. PLoS One 9:e98042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chintamani M, Abbott-Ozug V, Dunn MM, Bush K. 2014. Morphological and biochemical effects of ceftaroline on Enterobacteriaceae. Abstr 114th Annu Meet Am Soc Microbiol 2014 American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asli A, Brouillette E, Krause KM, Nichols WW, Malouin F. 2016. Distinctive binding of avibactam to penicillin-binding proteins of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:752–756. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02102-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Georgopapadakou NH, Smith SA, Sykes RB. 1982. Mode of action of azthreonam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 21:950–956. doi: 10.1128/AAC.21.6.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Y, Bhachech N, Bush K. 1995. Biochemical comparison of imipenem, meropenem and biapenem: permeability, binding to penicillin-binding proteins, and stability to hydrolysis by beta-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother 35:75–84. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alm RA, Johnstone MR, Lahiri SD. 2015. Characterization of Escherichia coli NDM isolates with decreased susceptibility to aztreonam/avibactam: role of a novel insertion in PBP3. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:1420–1428. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall S, Hujer AM, Rojas LJ, Papp-Wallace KM, Humphries RM, Spellberg B, Hujer KM, Marshall EK, Rudin SD, Perez F, Wilson BM, Wasserman RB, Chikowski L, Paterson DL, Vila AJ, van Duin D, Kreiswirth BN, Chambers HF, Fowler VG Jr, Jacobs MR, Pulse ME, Weiss WJ, Bonomo RA. 2017. Can ceftazidime-avibactam and aztreonam overcome β-lactam resistance conferred by metallo-β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02243-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02243-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shields RK, Chen L, Cheng S, Chavda KD, Press EG, Snyder A, Pandey R, Doi Y, Kreiswirth BN, Nguyen MH, Clancy CJ. 2017. Emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance due to plasmid-borne blaKPC-3 mutations during treatment of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02097-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02097-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]