ABSTRACT

The multidrug efflux system MexEF-OprN is produced at low levels in wild-type strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. However, in so-called nfxC mutants, mutational alteration of the gene mexS results in constitutive overexpression of the pump, along with increased resistance of the bacterium to chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, and trimethoprim. In this study, analysis of in vitro-selected chloramphenicol-resistant clones of strain PA14 led to the identification of a new class of MexEF-OprN-overproducing mutants (called nfxC2) exhibiting alterations in an as-yet-uncharacterized gene, PA14_38040 (homolog of PA2047 in strain PAO1). This gene is predicted to encode an AraC-like transcriptional regulator and was called cmrA (for chloramphenicol resistance activator). In nfxC2 mutants, the mutated CmrA increases its proper gene expression and upregulates the operon mexEF-oprN through MexS and MexT, resulting in a multidrug resistance phenotype without significant loss in bacterial virulence. Transcriptomic experiments demonstrated that CmrA positively regulates a small set of 11 genes, including PA14_38020 (homolog of PA2048), which is required for the MexS/T-dependent activation of mexEF-oprN. PA2048 codes for a protein sharing conserved domains with the quinol monooxygenase YgiN from Escherichia coli. Interestingly, exposure of strain PA14 to toxic electrophilic molecules (glyoxal, methylglyoxal, and cinnamaldehyde) strongly activates the CmrA pathway and upregulates MexEF-OprN and, thus, increases the resistance of P. aeruginosa to the pump substrates. A picture emerges in which MexEF-OprN is central in the response of the pathogen to stresses affecting intracellular redox homeostasis.

KEYWORDS: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, efflux, MexEF-OprN, CmrA, electrophilic stress, efflux pumps

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a Gram-negative pathogen of major clinical importance, is notorious for its ability to develop a high level of resistance to multiple antibiotics and cause hard-to-treat infections (1). When upregulated upon mutations in regulatory genes, RND (resistance nodulation cell division) efflux pumps contribute substantially to multiresistance in clinical isolates (2). One of these systems, MexEF-OprN, is able to export fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim (TMP), and chloramphenicol (CHL) (3). This tripartite pump is regulated by MexT, a LysR-like activator, whose gene (mexT) is located upstream from operon mexEF-oprN (4). The stable overproduction of MexEF-OprN in so-called nfxC mutants increases the resistance levels for all the pump substrates by 2- to 16-fold, while the MICs of carbapenems increase from 2- to 4-fold as a result of concurrent MexT-dependent downregulation of porin OprD (3). The reduced expression of RND pumps MexAB-OprM and MexXY/OprM observed in these mutants has been proposed to account for the paradoxical hypersusceptibility to penicillins, cephalosporins, and aminoglycosides (5). In addition, nfxC mutants are deficient in the production of some extracellular virulence factors, such as pyocyanin, elastase, and rhamnolipids, and exhibit reduced activity of the type III secretion system compared to its activity in wild-type strains (6, 7). Such impaired virulence involves the pump itself, which is thought to export some precursors of the quorum-sensing signal molecule PQS (Pseudomonas quinolone signal) (8). Additionally, it also involves the action of MexT, acting as a global regulator of gene expression (9).

Most nfxC mutants harbor disruptive mutations in gene mexS, predicted to encode a quinone oxidoreductase (10). Suppression of MexS activity in P. aeruginosa activates the regulator MexT, which in turn triggers the transcription of the operon mexEF-oprN. We recently showed that in the clinical setting, most of the MexEF-OprN-overproducing mutants studied either harbored single-amino-acid substitutions in MexS or contained wild-type copies of mexS and mexT genes (11). Furthermore, it appeared that none of the other genes previously reported to upregulate mexEF-oprN expression in vitro (ampR, mvaT, parRS, mxtR, and brlR [12–16]) was mutated in these isolates, indirectly suggesting the existence of additional regulatory loci controlling mexEF-oprN expression.

The present study was thus undertaken to decipher the complex regulation and to gain insight into the physiological function of this efflux system. Analysis of in vitro mutants derived from reference strain PA14 has led to the identification of a novel regulator of MexEF-OprN, CmrA, that responds to electrophilic stress.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In vitro selection of chloramphenicol-resistant mutants overproducing MexEF-OprN.

A previous study on multidrug-resistant clinical strains of P. aeruginosa showed that the active efflux system MexEF-OprN can be constitutively upregulated in mutants producing intact MexS and MexT proteins (11). In order to identify novel regulators of this pump, we carried out the selection of spontaneous mutants overproducing MexEF-OprN from reference strain PA14 on agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol at 128, 256, and 512 μg ml−1. In contrast to most isolates of the PAO1 lineage, PA14 (chloramphenicol MIC of 64 μg ml−1) harbors functional mexS and mexT genes, which makes it suitable for such experiments (11). Thirty resistant colonies were randomly selected under each condition (90 colonies) and further screened by the disk diffusion method for increased resistance to ciprofloxacin (CIP) and imipenem compared to that of the parent strain PA14 (data not shown). Typical nfxC mutants indeed exhibit cross-resistance to chloramphenicol, fluoroquinolones, and carbapenems (3). Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) experiments revealed that 40 subselected mutants significantly overexpressed mexE (from 34- to 116-fold more than in PA14; data not shown). Of these 40 mutants, 24 harbored indels disrupting gene mexS (mutation rate of 2.5 × 10−7), and 12 produced single-amino-acid variants of protein MexS (1.4 × 10−7). Interestingly, the remaining four mutants appeared to have intact mexS and mexT genes (2.5 × 10−8). We focused our attention on the latter mutants, named PJ01, PJ02, PJ03, and PJ04 (collectively referred to as PJ mutants below). All of them exhibited an nfxC-type resistance profile, characterized by 8- to 16-fold increases in the MICs of ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim relative to those of PA14 (Table 1). Interestingly, these resistance levels were somewhat lower than those of the nfxC control strain PA14ΔmexS. Other features of nfxC strains were also less pronounced in PJ mutants, such as the resistance to imipenem and the hypersusceptibility to the MexXY substrate gentamicin, although the MICs of aztreonam (a MexAB-OprM substrate) were identical (Table 1). Likewise, the production of virulence factors, such as pyocyanin, biofilm formation, and swarming motility, was less compromised in these mutants than in PA14ΔmexS (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Consistent with these observations, all these phenotypic traits were associated with relative abundances of mexE transcripts that were 1.5- to 3.4-fold lower than in PA14ΔmexS. The decreases in the relative expression of genes oprD, mexB, and mexY were also comparatively smaller in the PJ mutants (Table 1). Because of all the genetic and phenotypic differences described above, this new type of MexEF-OprN-upregulated mutants was dubbed nfxC2.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of nfxC2 mutants

| Strain | CmrA sequence variation | Transcript level ofa: |

MIC (μg ml−1) ofb: |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cmrA | mexE | mexS | mexT | oprD | mexB | mexY | CIP | CHL | TMP | IPM | ATM | GEN | ||

| PA14 | WT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.125 | 64 | 64 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| PA14ΔmexS | WT | 0.6 | 116 | ND | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 4 | 2,048 | 1,024 | 4 | 2 | 0.25 |

| PA14ΔmexT | WT | 1 | 0.4 | 1.1 | ND | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.125 | 64 | 64 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| PJ01 | A68V | 71 | 38 | 5.6 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1 | 1,024 | 512 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 |

| PJ02 | H204L | 84 | 34 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1 | 1,024 | 512 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 |

| PJ03 | L89Q | 53 | 74 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2 | 2,048 | 1,024 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 |

| PJ04 | N214K | 120 | 62 | 2.8 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2 | 2,048 | 1,024 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 |

| PA14ΔcmrA | —c | ND | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.125 | 64 | 64 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| PJ01ΔcmrA | — | ND | 0.6 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.125 | 64 | 64 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| PA14ΔcmrAPA14 | WT | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.125 | 64 | 64 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| PA14ΔcmrAPJ01 | A68V | 68 | 29 | 6.1 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1 | 512 | 256 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 |

| PJ01ΔmexT | WT | 76 | <0.1 | 1.3 | ND | 2.7 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.125 | 64 | 64 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| PJ01ΔmexS | WT | 70 | <0.1 | ND | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.125 | 64 | 64 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

Expressed as the ratio to the value for wild-type reference strain PA14. Mean values were calculated from two independent bacterial cultures each assayed in duplicate. ND, not determined.

CIP, ciprofloxacin; CHL, chloramphenicol; TMP, trimethoprim; IPM, imipenem; ATM, aztreonam; GEN, gentamicin.

—, strain lacks the gene.

A novel gene implicated in regulation of mexEF-oprN.

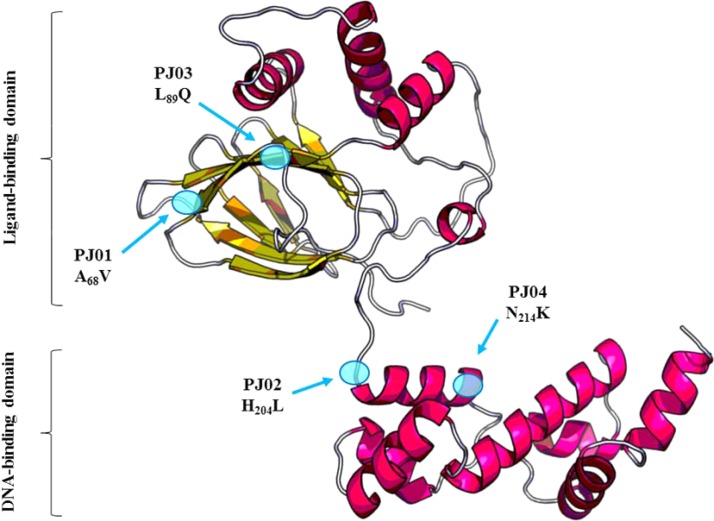

Sequencing of genes mexT, mvaT, ampR, and mxtR, known to influence in vitro the expression of the operon mexEF-oprN (12, 13, 15), did not reveal any mutations in the PJ mutants. Therefore, three of them (PJ01, PJ03, and PJ04) were submitted to whole-genome sequencing. Alignment of the sequence reads from PJ01 (n = 1,041,118), PJ03 (n = 1,290,598), and PJ04 (n = 1,443,653) with the strain UCBPP-PA14 genome revealed the existence of three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in each of the mutants tested (Table S1). In an interesting way, it appeared that all of them harbored different SNPs in the same gene, PA14_ 38040. These results were confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing. Compared to the sequence of PA14, the mutations were predicted to generate amino acid substitutions A68V (a change of A to V at position 68), L89Q, and N214K in the encoded products of PJ01, PJ03, and PJ04, respectively (Table 1). Subsequent sequencing of the last mutant, PJ02, also revealed an H204L substitution in the same protein. According to the GenBank database, gene PA14_38040 codes for an as-yet-uncharacterized transcriptional regulator of the AraC family. This gene was named cmrA (for chloramphenicol resistance Activator), referring to the conditions of selection of PJ mutants. Interestingly, it turned out that the relative expression of gene cmrA was upregulated in all PJ mutants (from 53- to 120-fold that of PA14), indicating that CmrA likely activates its own gene transcription (Table 1).

Role of CmrA in antibiotic resistance.

To confirm the potential implication of CmrA in mexEF-oprN activation and, thus, the resistance phenotype of PJ mutants, we deleted the coding sequence of cmrA in both PJ01 and PA14, yielding PJ01ΔcmrA and PA14ΔcmrA, respectively. The MICs of MexEF-OprN substrates (ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim) and of carbapenems (imipenem) were restored to wild-type levels in PJ01ΔcmrA but remained unchanged for PA14ΔcmrA (Table 1). These results clearly demonstrated that CmrA activates the efflux operon in mutant PJ01 but does not contribute to the intrinsic resistance of P. aeruginosa to the drugs tested. Moreover, deletion of cmrA in PJ01 restored the wild-type susceptibility to β-lactams (aztreonam) and to aminoglycosides (gentamicin), cancelling the negative impact of overproduced MexEF-OprN on efflux pumps MexAB-OprM and MexXY, respectively. To confirm these data, we inserted a single copy of the cmrA allele from PJ01 into the chromosome of PA14ΔcmrA (to yield PA14ΔcmrAPJ01). As expected, PA14ΔcmrAPJ01 displayed a resistance profile similar to that of PJ01, whereas the control strain complemented with the wild-type cmrA allele, PA14ΔcmrAPA14, remained fully susceptible to all the antibiotics tested (Table 1). PA14ΔcmrAPJ02, PA14ΔcmrAPJ03, and PA14ΔcmrAPJ04 were phenotypically similar to PA14ΔcmrAPJ01 (data not shown). Finally, as shown by the results in Table 2, overexpression of a plasmid-borne copy of the PJ01 cmrA allele [PA14(pJN105::cmrAPJ01)] was associated with increased resistance to ciprofloxacin (8-fold), chloramphenicol (8- to 16-fold), and to a lesser extent, trimethoprim (2- to 4-fold), concomitant with a 20- to 50-fold increase in mexE transcripts. Overexpression of the wild-type allele cmrA in PA14 had no significant effects on the susceptibility of the strain to antibiotics [see PA14(pJN105::cmrAPA14) in Table 2], reinforcing the idea that the CmrA peptide produced by PJ01 is under an activated conformation. According to the structure modeling of CmrA provided by the RaptorX Web server (17), the amino acid substitutions A68V and L89Q reside in the putative N-terminal ligand-binding domain, while H204L and N214K are located in the C-terminal DNA-binding domain of the protein (Fig. 1). Altogether, these findings showed that CmrA is a novel regulator of the AraC family, able to trigger directly or indirectly the expression of mexEF-oprN when constitutively activated by single-amino-acid substitutions located in two different functional domains of the protein.

TABLE 2.

Impact of overexpression of cmrA and PA2048

| Transformant | Value without (with) arabinose fora: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcript levelb |

MIC (μg ml−1)c |

|||||

| cmrA | PA2048 | mexE | CIP | CHL | TMP | |

| PA14(pJN105) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.125 (0.125) | 128 (128) | 128 (128) |

| PA14(pJN105::cmrAPA14) | 385 (>1,000) | 4.5 (3.8) | 1.1 (1.3) | 0.125 (0.125) | 128 (128) | 128 (128) |

| PA14(pJN105::cmrAPJ01) | 458 (>1,000) | 35 (53) | 20 (50) | 1 (1) | 1,024 (2,048) | 256 (512) |

| PA14(pJN105::PA2048) | 1.6 (4.1) | 135 (>1,000) | 52 (270) | 1 (2) | 1,024 (2,048) | 256 (512) |

Values obtained without and with 0.5% arabinose, used as an inducer of gene expression.

Expressed as the ratio to the value for PA14(pJN105).

CIP, ciprofloxacin; CHL, chloramphenicol; TMP, trimethoprim.

FIG 1.

RaptorX prediction of CmrA structure. A three-dimensional structure of the regulator CmrA was modeled using the RaptorX Web server (http://raptorx.uchicago.edu/). The putative N-terminal ligand-binding domain (from amino acid position 40 to 191) was predicted based on ToxT from Vibrio cholerae (PDB 3GBG; P = 5.96e−4), while the putative C-terminal DNA-binding domain (from 198 to 310) is based on AdpA from Streptomyces griseus (PDB 3W6V; P = 3.45e−5). The amino acid substitutions found in PJ mutants are highlighted by blue spots.

Characterization of cmrA locus.

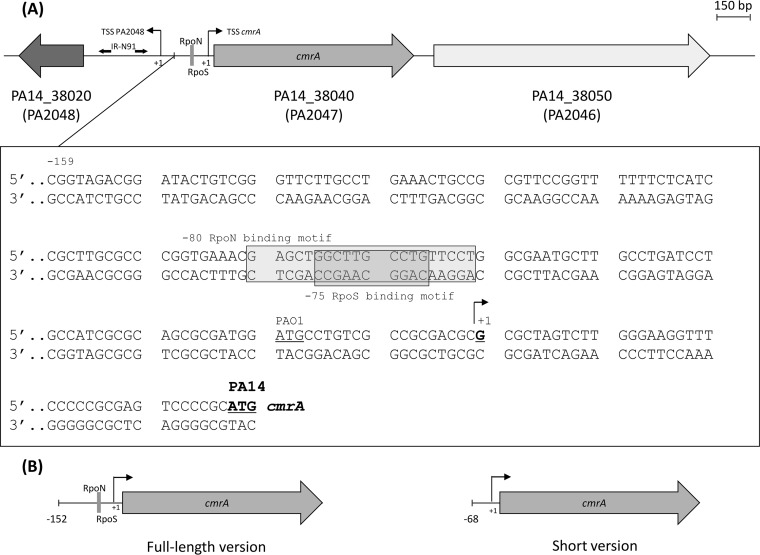

The cmrA gene is highly conserved among P. aeruginosa strains. Homologs were found in PAO1 (PA2047, 99% sequence identity), PACS2 (AOK_RS09840, 98%), and LESB58 (PALES_30281, 98%). However, in strain PAO1 (18), a potential start codon (ATGPAO1) has been mapped 57 nucleotides upstream from that of PA14 (ATGPA14), leading to a translated peptide of 329 amino acids instead of 310 (Fig. 2A). In silico analysis of the upstream region of both ATGs failed to show any putative ribosome binding site (RBS) sequence, which could have helped us to define the correct start codon of cmrA. We thus carried out 5′-RACE (rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends) experiments to identify the transcription start site (TSS) of the gene. Sequencing analysis of the 5′-RACE product revealed that the cmrA TSS is a guanine residue located 19 bp downstream from the proposed ATGPAO1, a result that contradicts this annotation but validates that of PA14, with the TSS (+1) located 38 bp upstream from ATGPA14 (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Genetic environment of gene cmrA. (A) Gene annotations are those available in GenBank for strain PA14 (RefSeq accession number NC_008463.1). Homologs in strain PAO1 are indicated in brackets. The DNA sequence upstream from cmrA is shown below the schematic. Different positions were assigned to the start codon of cmrA in genomic maps of PA14 (PA14_38040, 933 bp; boldface and underlined) and PAO1 (PA2047, 990 bp; underlined). Two putative overlapping RpoN and RpoS binding motifs are highlighted in gray. The transcription start sites (TSS, +1) of cmrA and PA2048 were mapped by 5′-RACE at −38 bp and −315 bp, respectively. The 5′ UTR of PA2048 contains a 111-bp region of unknown function, bordered by two 10-bp inverted repeats (IR-N91). (B) Complementation experiments in mutant PA14ΔcmrA were carried out to clarify the role of the σ factor binding sites in cmrA expression. A full-length DNA fragment from mutant PJ01, carrying cmrA and the RpoN/RpoS binding sites (−152 bp upstream from the TSS), conferred an nfxC2 resistance phenotype on PA14ΔcmrA, while a short version lacking the RpoN/RpoS binding sites (−68 bp) did not. The whole sequence of cmrA and its 5′ UTR is accessible through the GenBank database (accession number KX274690).

Analysis of the putative sigma factor binding motifs (SFBMs) of PA14 (sigmulome) (19) proved to be useful to predict the location of the cmrA promoter (PcmrA). Hence, comparison of the DNA region upstream from cmrA TSS with the PA14 sigmulome highlighted the presence of two overlapping SFBMs for RpoN (−80 bp) and RpoS (−75 bp) (Fig. 2A). cis complementation of strain PA14ΔcmrA with a fragment containing cmrA preceded by the full-length RpoN/RpoS binding region (−152 bp upstream from the TSS, Fig. 2B) successfully generated an nfxC2 resistance phenotype, while complementation with a shorter fragment lacking the RpoN/RpoS SFBMs (−68 bp upstream from the TSS) had no effect (data not shown). These data provide evidence that the RpoN/RpoS region is necessary to activate the expression of cmrA (19). Whether cmrA is under the control of RpoN and/or RpoS remains to be determined.

MexT- and MexS-dependent upregulation of the operon mexEF-oprN in nfxC2 mutants.

Because the upregulation of mexEF-oprN requires a functional regulator, MexT, in mexS mutants (5), we examined whether this also applies to cmrA mutants. Inactivation of mexT in PJ01 (PJ01ΔmexT) (Table 1) restored a wild-type profile, thereby demonstrating MexT-dependent activation of MexEF-OprN in nfxC2 mutants. In agreement with these data, the transcript levels of mexE were strongly reduced in the absence of mexT (>380-fold), while those of genes oprD, mexB, and mexY increased significantly, from 2.7- to 5-fold (Table 1).

Finally, as the inactivation of mexS is the main mutational cause of mexEF-oprN overexpression in both in vitro (10) and clinical strains (11), we deleted this gene in PJ01 to see whether this would result in a stronger activation of the efflux operon and, thus, higher resistance levels. Surprisingly, loss of mexS in mutant PJ01ΔmexS totally abolished mexEF-oprN overexpression and restored a PA14-like resistance phenotype (Table 1), a result that underlines a functional link between MexS and CmrA or between MexS and one or several genes under the control of CmrA. Again, as for PJ01ΔmexT, the phenotypic changes noted in PJ01ΔmexS relative to PJ01 were associated with significant variations in the expression of genes mexE, oprD, mexB, and mexY. Similar results were obtained with the other mutants, PJ02ΔmexS, PJ03ΔmexS, and PJ04ΔmexS (data not shown).

Identification of genes regulated by CmrA.

To better understand the physiological role of CmrA and to identify the genes under its control, we performed a transcriptomic analysis by RNA-seq of cmrA mutant PJ01 in comparison with parental strain PA14. Since MexT regulates the expression of 143 genes in P. aeruginosa (20), we analyzed the transcriptome of mutant PJ01ΔmexT as well. This allowed us to identify, by subtraction, genes whose expression is exclusively regulated by CmrA. Data analysis showed that 53 genes were differentially expressed between mutant PJ01 and strain PA14, 26 of them being upregulated and 27 downregulated in PJ01 (threshold fixed at 3.0-fold) (GEO accession number GSE86211) (see Fig. S2). Comparison of strains PA14 and PJ01ΔmexT allowed the identification of 42 genes under the control of MexT and only a small set of 11 CmrA-dependent upregulated genes clustering into three genetic loci (Table 3). The overexpression of these 11 genes was confirmed by RT-qPCR. Altogether, our data showed that CmrA is a transcriptional activator influencing the expression of a few genes, including cmrA itself (Table 3). Reminiscent of the putative function of MexS, the four most activated CmrA-dependent genes (homologs of PA2048, PA1881, PA1880, and PA2275 in PAO1) are predicted to encode oxidoreductases (a quinol monooxygenase, an oxidoreductase, an aldehyde dehydrogenase, and an alcohol dehydrogenase, respectively). Furthermore, it appeared that CmrA also regulates the expression of two genes coding for uncharacterized transcriptional regulators (PA2276 and PA1879) and the determinant of the arsenic/antimony response regulator ArsR (PA2277) (21). Whether CmrA directly regulates all these genes remains to be determined.

TABLE 3.

CmrA-dependent genes

| Genea | PAO1 homologa | Name | Fold change usingb: |

Predicted product | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq | RT-qPCR | ||||

| PA14_40180 | PA1881 | 115 | 130 | Oxidoreductase | |

| PA14_40200 | PA1880 | 104 | 152 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| PA14_40210 | PA1879 | 4 | ND | Transcriptional regulator | |

| PA14_38010 | PA2049 | 13 | 5 | Metallophosphatase superfamily protein | |

| PA14_38020 | PA2048 | 199 | 154 | Quinol monooxygenase YgiN | |

| PA14_38040 | PA2047 | cmrA | 41 | 74 | AraC family transcriptional regulator CmrA |

| PA14_38050 | PA2046 | 9 | 13 | Hypothetical protein | |

| PA14_35130 | PA2277 | arsR | 3 | ND | Transcriptional repressor ArsR |

| PA14_35140 | PA2276 | 21 | 22 | AraC family transcriptional regulator | |

| PA14_35150 | PA2275 | 62 | 137 | Alcohol dehydrogenase | |

| PA14_35160 | PA2274 | 9 | 10 | Flavin-dependent monooxygenase | |

Gene number from the Pseudomonas Genome Project (http://pseudomonas.com/).

Gene expression in PJ01ΔmexT relative to that in PA14.

PA2048 is responsible for the nfxC2 phenotype.

Single inactivation of the CmrA-dependent genes in mutant PJ01 revealed that none of them was implicated in mexEF-oprN overexpression except PA2048, the deletion of which restored a wild-type phenotype of resistance to the selected antibiotics (Table S2). PA2048 is adjacent to and divergently transcribed from cmrA (Fig. 2).

Because a long intergenic region of 581 bp between cmrA and PA2048 was mentioned in the annotated genomes of PAO1 and PA14 (18), we carried out 5′-RACE experiments to localize the TSS of PA2048. Our results confirmed that the transcript of PA2048 begins 315 nucleotides upstream from ATGPA2048 as determined in the PA14 sigmulome (19). This long untranslated region (UTR) contains two inverted repeat sequences of 10 nucleotides with a spacer of 91 nucleotides (Fig. 2, IR-N91), the function of which remains unknown. ATGPA2048 is preceded by a potential Shine-Dalgarno sequence (AGGAGG) of 8 bp upstream from the gene coding sequence.

PA2048 codes for a small hypothetical protein of 98 amino acids, sharing conserved domains with YgiN from Escherichia coli (NCBI pblast). Sequence alignment with Clustal Omega (22) showed 40% similarity between YgiN (protein accession number ABV07440) and PA2048 (protein accession number WP_003088696) (Fig. S3). YgiN was initially described as a small protein of 104 residues having orthologs in other bacterial species, such as Bacillus subtilis, Synechocystis sp., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Rhodococcus erythropolis, but whose function was completely unknown (23). Subsequent analysis of the crystal structure of YgiN revealed a folding similar to that of monooxygenase ActVA-Orf6 from Streptomyces coelicolor, an enzyme that uses quinols as substrates (24). Consistent with this, in vitro experiments demonstrated that the purified YgiN protein was able to oxidize menadiol into menadione without the need of any cofactor, data that allowed the classification of this enzyme as a quinol monooxygenase (24).

Quinol monooxygenases are usually functionally coupled with oxidoreductases that catalyze inverse reactions (quinones to quinols) and so participate in a quinone redox cycle, as previously illustrated by MdaB-YgiN and YdhR-YdhS in E. coli (24, 25). Later on, Adams and Jia showed that the coordinate activity of MdaB-YgiN allows bacterial cells to resist polyketide antibiotics, such as adriamycin and tetracycline (26). It was proposed that this enzymatic couple might function primarily to protect E. coli cells from polycyclic quinones by recycling them until they are conjugated and exported out of the cell (26). YgiN would also be involved in cell respiration by transferring electrons to molecular oxygen when cytochrome oxidases are deficient (27). Interestingly, our results suggest that, in P. aeruginosa, the activities of PA2048 (a putative quinol monooxygenase) and MexS (a putative quinone oxidoreductase) are functionally linked, perhaps to adjust the redox state of the respiratory quinone pool when bacteria face some stressful conditions. In support of this assumption, we found that mexS expression was increased from 2.3- to 5.6-fold in the PA2048-upregulated PJ mutants compared with its expression in PA14 (Table 1). To our knowledge, quinol monooxygenases have never been studied so far in Pseudomonas species and the physiological role of PA2048 remains to be explored.

Since PA2048 was the most upregulated gene (199-fold) of the PJ01 transcriptome (Table 3), a plasmid-borne copy of this gene (including its 5′ UTR) was overexpressed in strain PA14 to determine whether the nfxC2 phenotype results exclusively from the activity of the encoded protein. Indeed, overexpression of PA2048 in PA14(pJN105::PA2048) strongly increased mexE transcripts, as well as the MICs of the pump substrates, without a significant change in the cmrA expression level (Table 2). These data clearly confirmed that CmrA is not directly responsible for the activation of mexEF-oprN in mutant PJ01 but exerts an indirect effect on the pump through the product of PA2048.

The CmrA pathway is activated by electrophilic stress.

To screen for inducers of the CmrA pathway, we constructed a transcriptional fusion between PA2048 and the luxCDABE operon. Gene PA2048 was selected for the lux fusion because its expression is highly augmented in response to CmrA activation (i.e., as in mutant PJ01), and its encoded product is key in the regulatory cascade that finally triggers production of MexEF-OprN via MexS and MexT. Gene PA2048 was fused to the lux reporter and inserted into the chromosomes of PA14 and PJ01. As expected, PJ01::PA2048-lux emitted 10-fold more luminescence than PA14::PA2048-lux at the mid-log phase of growth (data not shown).

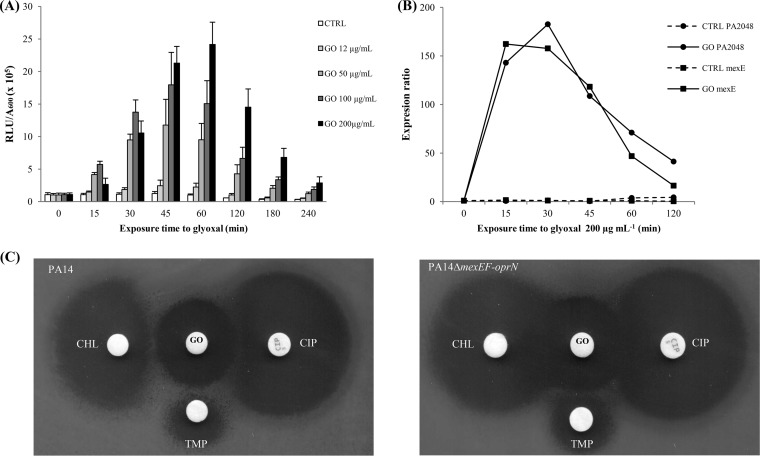

A first set of experiments using known MexEF-OprN substrates (ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim, and chloramphenicol) failed to demonstrate any induction of the lux reporter in strain PA14 (data not shown). The same negative results were obtained when disulfide stress (diamide) (28), oxidative stress (H2O2, paraquat, and dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]), and nitrosative stress (S-nitrosoglutathione [GSNO] and 2-n-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline N-oxide [HQNO]) (29) elicitors were added at subinhibitory concentrations to the bacterial cultures (data not shown). Finally, we found that three CmrA-regulated proteins (PA2048, PA2275, and PA2276) share ≥40% amino acid similarity with E. coli enzymes implicated in the response to electrophilic stress (YgiN, YqhD, and YqhC, respectively) (30, 31). This cellular stress is characterized by an imbalance between the formation and the removal of reactive electrophilic species (RES) containing α,β-unsaturated carbonyl (32) or other electrophilic groups (33). For this reason, strain PA14::PA2048-lux was challenged with increasing concentrations of three toxic electrophilic molecules: glyoxal (GO), methylglyoxal (MG) (33), and cinnamaldehyde (CNA) (34). Interestingly, the PA2048-lux-dependent luminescence increased with subinhibitory concentrations of GO (12 to 200 μg ml−1) (Fig. 3A), MG (10 to 100 μg ml−1), and CNA (70 to 280 μg ml−1) (Fig. S4).

FIG 3.

Response of P. aeruginosa to electrophilic stress. (A) The bioluminescence of strain PA14::PA2048-lux was monitored at defined time points after exposure to increasing concentrations of glyoxal (GO) and is expressed as the ratio of relative light units (RLU) to bacterial density (A600). Nontreated bacteria were used as the control (CTRL). Results are mean values ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. (B) Expression levels of genes mexE and PA2048 were determined by RT-qPCR in strain PA14 exposed to 200 μg ml−1 GO and compared with those of a nontreated control (CTRL). Results are mean values of four determinations from two independent experiments. (C) Induction of pump MexEF-OprN with glyoxal was assessed by a double-disk antagonism test using strain PA14 and negative-control strain PA14ΔmexEF-oprN. Paper disks were loaded with 8,000 μg glyoxal (GO), 5 μg ciprofloxacin (CIP), 1,000 μg chloramphenicol (CHL), or 240 μg trimethoprim (TMP). Antagonism is visible between GO and all the tested MexEF-OprN substrates in strain PA14 (left) but not in mutant PA14ΔmexEF-oprN (right).

To confirm these results, the impacts of electrophilic stress on mexE and PA2048 expression were then assessed by RT-qPCR. As shown by the results in Fig. 3B, both genes were rapidly and strongly activated 15 min after the addition of 200 μg ml−1 GO to the bacterial cultures. The same was observed for cmrA, whose mRNA levels increased 67-fold over those of the untreated control (data not shown). Confirming our bioluminescence data, the transcript amounts of mexE and PA2048 started to decline 45 min after the initiation of electrophilic stress. Finally, induction of the MexEF-OprN efflux system upon GO exposure was phenotypically confirmed in strain PA14 with antibiograms on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA), showing antagonistic interactions between (i) disks containing MexEF-OprN antibiotic substrates (chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and trimethoprim) and (ii) a disk loaded with GO (Fig. 3C). As anticipated, no evidence of antagonism was visible with the negative-control strain PA14ΔmexEF-oprN. Identical results were obtained when the double-disk tests were performed with MG and CNA (data not shown).

Differential activation of detoxification mechanisms by electrophilic stress elicitors.

In E. coli, GO and MG are rapidly sequestered under the form of glutathione adducts and transformed into nontoxic metabolites (glycolic acid and lactate, respectively) via enzymes of the glyoxalase system (32, 33, 35). Suggesting the existence of a similar detoxification pathway, two glyoxalase genes (36) turned out to be significantly overexpressed in strain PA14 when treated with GO (gloA2 and gloA3) or MG (gloA3) (Table S3). It should be noted that activation of the glyoxalase genes is not CmrA dependent, as their expression remains unchanged in mutant PA14ΔcmrA treated with either GO or MG (data not shown). Conversely, CNA exposure failed to activate the glyoxalase pathway, while it dramatically triggered the expression of another gene, PA2275 (2,873-fold compared to its expression in untreated cells). In comparison, GO and MG treatments had smaller effects on PA2275 transcription levels (17- and 7-fold, respectively) (Table S3). The PA2275-encoded product shares 40% sequence similarity with YqhD from E. coli, an enzyme promoting the degradation of CNA into the less-toxic cinnamic alcohol (31, 37). Altogether, these results corroborate the hypothesis that the transient activation of CmrA by GO, MG, and CNA is due to the rapid degradation of these molecules into metabolites lacking electrophilic properties, via different bacterial enzymes.

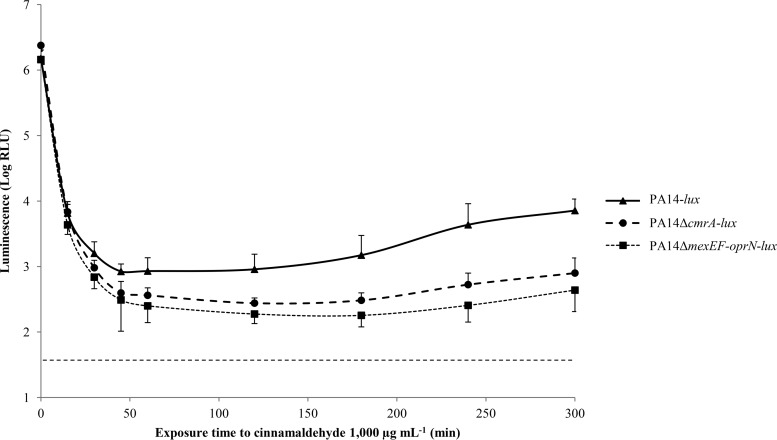

MexEF-OprN efflux pump protects bacteria from cinnamaldehyde.

Since MexEF-OprN is overproduced in response to electrophilic stress, we wondered whether the pump offers protection against the agents able to elicit such a stress. Surprisingly, the resistance levels to GO (MIC of 512 μg ml−1), MG (256 μg ml−1), and CNA (512 μg ml−1) were not different between strain PA14 and mutant PA14ΔmexEF-oprN, consistent with the idea that this efflux system does not contribute to the intrinsic resistance toward any of these products. Alternatively, efflux of the elicitors might be masked by the effects of more efficient detoxification mechanisms, such as those described above. To test this hypothesis, time-kill experiments were performed with bactericidal concentrations of GO (1,000 μg ml−1), MG (500 μg ml−1), and CNA (1,000 μg ml−1) on bioluminescent strains PA14-lux, PA14-lux-ΔmexEF-oprN, and PA14-lux-ΔcmrA. While no differences were observed between the killing curves of the three strains exposed to GO or MG (data not shown), deletion of mexEF-oprN or cmrA was associated with a slight though reproducible sensitization of bacteria to CNA killing that impaired bacterial regrowth 45 min after drug exposure (Fig. 4). Since mutants PA14-lux-ΔmexEF-oprN and PA14-lux-ΔcmrA behaved similarly, the simplest explanation for these results is that the CmrA-dependent activation of MexEF-OprN allows surviving bacteria to better resist CNA (but not GO or MG) through the potentiation of detoxification mechanisms.

FIG 4.

Bactericidal activity of cinnamaldehyde on P. aeruginosa. Bioluminescent strain PA14-lux and its derived mutants PA14-lux-ΔcmrA and PA14-lux-ΔmexEF-oprN were cultured to mid-log phase and then challenged with 1,000 μg ml−1 cinnamaldehyde. Bioluminescence (RLU) was recorded every 30 min and used as an indicator of cell survival. RLU values are mean values ± standard deviations from three independent experiments. A bioluminescence threshold was established with sterile MHB (dotted line).

Conclusion.

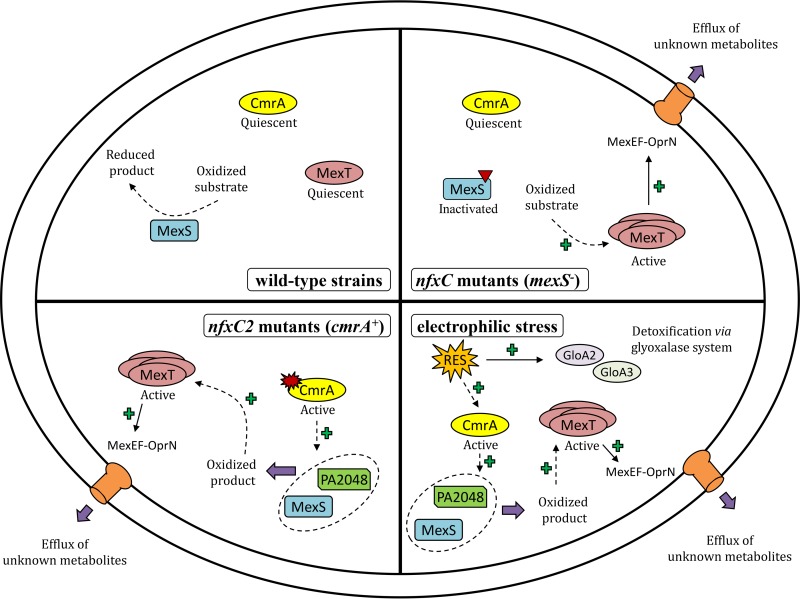

This work describes a novel regulator of the AraC family, named CmrA, which when activated by single point mutations or electrophilic stressors is able to upregulate the expression of mexEF-oprN via MexS and MexT. The cmrA mutants (dubbed nfxC2) exhibit the same, albeit less pronounced, multidrug resistance phenotype as prototypal nfxC mutants. Consistent with lower expression of the operon mexEF-oprN and, probably, lower levels of activation of the regulator MexT, nfxC2 mutants are less compromised than their nfxC counterparts in quorum-sensing-dependent production of virulence factors (6).

CmrA influences the expression of a very small set of nonessential genes all predicted to catalyze redox reactions on as-yet-undetermined substrates. The overexpression of one of these genes, PA2048, coding for a presumed quinol monooxygenase, is sufficient to trigger MexEF-OprN production. However, our observation that MexEF-OprN is overproduced only when the putative quinone oxidoreductase MexS is functional in nfxC2 mutants indicates that both enzymes are functionally linked, at least under specific physiological or stress conditions. Whether these two enzymes act coordinately or sequentially to maintain the redox state of respiratory quinones in stressed cells is currently being investigated. Therefore, the present work reinforces the conclusions reached by previous investigators on MexT being a redox-responsive regulator (28), though it introduces a new player, PA2048, in the activation pathway of MexT and MexEF-OprN. Interestingly, while MexT activation requires a functional MexS in nfxC2 mutants, it is triggered by the loss of this enzyme in nfxC strains (Fig. 5). The fact that PA2048 is the only CmrA-regulated gene whose deletion abolishes MexEF-OprN activation in nfxC2 mutants suggests that the metabolites of putative quinol monooxygenase PA2048 are directly or indirectly processed by MexS to form the ligand(s) that, in fine, will cause the oligomerization of MexT, as suggested previously (28). The absence of exogenous stress in the CmrA mutants PJ01 to PJ04 demonstrates that the substrates of PA2048 are endogenous molecules. Furthermore, this strongly suggests that the mutations that drive the enzyme overproduction generate an imbalance in the redox state of preexisting compounds that MexS tends to compensate (i.e., note that gene mexS is overexpressed in the PJ mutants). Whether the MexS metabolites are effluxed by MexEF-OprN or only serve as a signal to activate the pump as part of a global response of defense remains to be elucidated.

FIG 5.

Schematic representation of activation pathways of MexEF-OprN in P. aeruginosa. In wild-type strains (top left), such as strain PA14, regulators MexT and CmrA remain quiescent because of redox homeostasis. In so-called nfxC mutants (top right), mutational alteration of putative quinone oxidoreductase MexS is thought to result in intracellular accumulation of some redox-active MexS substrate(s). Redox-dependent oligomerization of MexT then triggers production of the pump MexEF-OprN and active efflux of still-undetermined endogenous products. In nfxC2 mutants (bottom left), regulator CmrA is activated as a result of gain-of-function mutations in gene cmrA. Among the 11 genes positively regulated by CmrA, PA2048 codes for a putative quinol monooxygenase. Concomitant activation of PA2048 and MexS is assumed to generate oxidized metabolites, the accumulation of which would modify the cellular redox state. As in MexS-deficient mutants, these changes upregulate the production of MexEF-OprN via MexT. Finally, upon electrophilic stress (bottom right), reactive electrophilic species (RES), such as glyoxal and methylglyoxal, induce the glyoxalase detoxification system (GloA2 and GloA3) and CmrA-dependent expression of MexEF-OprN. We propose that P. aeruginosa uses the efflux pump MexEF-OprN as a defense mechanism in response to toxic electrophilic stressors encountered in its environment.

Reactive electrophilic species (RES) are compounds containing α,β-unsaturated carbonyl or other electrophilic groups. These highly toxic molecules interact with proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and carbohydrates, generating pleiotropic cellular effects (31, 38). They also affect the redox state of the cell via their interaction with redox cofactors, such as glutathione and NAD(P)H (33). As such, the electrophilic stress can be considered a subcategory of oxidative stress, as is the case with disulfide (28) and nitrosative (29) stresses. Even if all these different subcategories of stress result in MexS/MexT-dependent upregulation of the efflux system MexEF-OprN, only electrophiles were found to specifically activate the CmrA pathway, highlighting a distinctive feature of these molecules despite their multiple cellular targets (Fig. 5) (31). Since MexEF-OprN does not provide P. aeruginosa with meaningful protection against harmful electrophiles, such GO and MG, our hypothesis is that the physiological damage generated by such agents mimics a stress the bacterium has to face when adapting to other challenging conditions, perhaps those encountered during infection. It should be noted that all the electrophiles tested were able to upregulate MexEF-OprN via CmrA, PA2048, and MexS. Thus, these results unambiguously show that MexT is activated not by gross changes in the redox state of the cytoplasm but by specific ligand molecules, likely produced by MexS. In contrast to GO and MG, cinnamaldehyde (CNA) seems to be a substrate of MexEF-OprN. This natural substance present in the cinnamon stem bark is well known for its antimicrobial properties against various fungi and bacteria, including P. aeruginosa (39). As an inducer and a substrate of the MexEF-OprN pump, CNA would be the first example of a plant substance against which P. aeruginosa has evolved an efflux-based defense triggered by electrophilic stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The reference strains, derived mutants, and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S4 in the supplemental material. All the bacterial cultures were grown in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) with adjusted concentrations of Ca2+ (from 20 to 25 μg ml−1) and Mg2+ (from 10 to 12.5 μg ml−1) (Becton Dickinson and Company, Cockeysville, MD) or on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). Spontaneous mutants overproducing the efflux pump MexEF-OprN were selected on MHA supplemented with chloramphenicol (128, 256, or 512 μg ml−1). Escherichia coli transformants were selected on MHA containing 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin (marker for vectors pCR-Blunt and pCR2.1), 15 μg ml−1 tetracycline (plasmids mini-CTX1 and miniCTX-lux), 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin (pKNG101), or 10 μg ml−1 gentamicin (pJN105 and pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-lux-Gm). Recombinant plasmids were introduced into P. aeruginosa strains by triparental mating and mobilization with the broad-host-range vector pRK2013 using E. coli HB101 as a helper strain (40). Transconjugants were selected on Pseudomonas isolation agar (PIA; Becton Dickinson and Company) supplemented with 200 μg ml−1 tetracycline, 2,000 μg ml−1 streptomycin, or 10 μg ml−1 gentamicin, as required. Excision of pKNG101 was obtained by subculture on M9 minimal medium (8.54 mM NaCl, 25.18 mM NaH2PO4, 18.68 mM NH4Cl, 22 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM MgSO4, pH 7.4) supplemented with 5% sucrose and solidified with 0.8% agar.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

The MICs of selected antibiotics were determined by the standard serial 2-fold dilution method in MHA with inocula of 104 CFU per spot, according to CLSI recommendations (41). Growth was visually assessed after 18 h of incubation at 37°C. Spontaneous nfxC mutants developing on solid medium were screened for their resistance to both ciprofloxacin and imipenem by measuring the inhibition zones around Bio-Rad disks (loaded at 5 μg and 10 μg, respectively) on MHA plates incubated for 18 h at 37°C (42).

Virulence factor analysis.

Biofilm formation was assessed in 96-well polystyrene plates after coloration of adherent bacteria with 1% (wt/vol) crystal violet (43). Swarming motility, which is characterized by the formation of bacterial dendrites on low-agar culture medium, was assayed on freshly prepared M8 medium (42.2 mM Na2HPO4, 22 mM KH2PO4, 7.8 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, 0.5% casein, 0.5% agar, and 1% glucose, as previously described (44). Finally, pyocyanin production was evaluated in the supernatants of 18-h cultures at 37°C in a specific broth [12 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.2, 0.1% tryptones, 20 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1.6 mM CaCl2, 10 mM KCl, 24 mM sodium citrate, and 50 mM glucose] (absorbance [A600] = 1.6 ± 0.2). The blue pigment was extracted with 1 volume of chloroform (45). Virulence assays were all repeated twice with independent cultures of strains PA14 and PA14ΔmexS as controls.

RT-qPCR experiments.

Specific gene expression levels were measured by quantitative PCR after reverse transcription (RT-qPCR), as described previously (46). Briefly, 2 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed with ImProm-II reverse transcriptase as specified by the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, WI). The amounts of specific cDNA were quantified on a Rotor-Gene RG6000 instrument (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) by using the QuantiFast SYBR green PCR kit (Qiagen). When not already published, the nucleotidic primers used for gene amplifications were designed from the sequences available in the Pseudomonas Genome Database, version 2, using primer3 Web software (Table S5) (47). For each strain, the mRNA levels of target genes were normalized to that of housekeeping gene rpsL and are expressed as the ratios to the transcript levels of strain PA14. Mean gene expression values were calculated from two independent bacterial cultures, each assayed in duplicate. Strain PA14ΔmexS was used as a positive control for the overexpression of gene mexE. As shown in previous experiments (11), transcript levels of mexE ≥20-fold those of PA14 are associated with a ≥2-fold increase in resistance to MexEF-OprN substrates, and such levels were considered significant.

SNP identification.

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between strain PA14 and its derived mutants PJ01, PJ03, and PJ04 were identified with the Ion Torrent technology (Life Technologies, CA). Briefly, genomic DNA of each strain was extracted and purified by using the PureLink genomic DNA minikit (Life Technologies). Ion Torrent libraries were prepared from 100 ng of each DNA preparation (Qubit 2.0 fluorometer; Invitrogen) using dedicated equipment (Veriti thermocycler and E-Gel iBase; Invitrogen). Alignment of the sequence reads (about 200 bp in length) of PJ01, PJ03, and PJ04 with the UCBPP-PA14 genome (NCBI accession number NC_008463.1) was performed using BioNumerics version 7.1 and led to the identification of potential sequence variations (SNPs). Identification of an SNP was considered reliable if the coverage was ≥20-fold and its percentage was ≥29%. Sequence variations were verified on both strands by capillary sequencing on an Applied Biosystems 3130 GA apparatus (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies; Courtaboeuf, France) after PCR amplification with the proper primers.

Identification of gene transcriptional start sites (+1).

Rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends (5′-RACE) was performed to identify the transcriptional start site (TSS) of cmrA with the 5′-RACE system, as recommended by Invitrogen. Briefly, total RNA from two independent cultures of cmrA-overexpressing mutant PJ01 was extracted at mid-log phase of growth (A600 = 1) using the RNeasy plus minikit (Qiagen) and was treated with RNase-free DNase (Qiagen). Five micrograms of total RNA was subjected to first-strand cDNA synthesis using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and the specific primer GSP1-PA2047 (Table S5). The presence of cDNA was checked by PCR using nested gene-specific primers GSP2-PA2047 (reverse) and GSP3-PA2047 (forward) (Table S5). A homopolymeric tail was then added to the 3′ cDNA using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and dCTP. PCR amplification was carried out using GSP2-PA2047, a deoxyinosine-containing abridged anchor primer (AAP), and poly(C)-tailed cDNA as the template. The 5′-RACE product was cloned into the pCR2.1 vector and further sequenced to allow the identification of the TSS of cmrA. The verification of PA2048 TSS, previously identified by Schulz et al., (19), was performed under the same conditions using specific primers GSP1-PA2048, GSP2-PA2048, and GSP3-PA2048 (Table S5).

High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) library construction.

Total RNA extracts were obtained in triplicate from exponential cultures (A600 = 1) of strains PA14, PJ01, and PJ01ΔmexT at 37°C. Bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation in RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen) and disrupted with 0.15- to 0.60-mm ceramic beads in a TissueLyzer II (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA was then purified from bead-beaten samples with the RNeasy plus 96 kit (Qiagen). The concentration and purity of the RNA extracts were assessed by RiboGreen measurement (Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA reagent and kit; Invitrogen) and by using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system (Agilent Technologies), respectively. Depletion of rRNA from those RNA samples was performed with the Ribo-Zero rRNA removal reagents (bacteria) from Epicentre (Madison, WI). Libraries were then constructed using the TruSeq stranded-mRNA high-throughout (HT) sample preparation kit from Illumina (San Diego, CA). The final libraries were quantified with PicoGreen fluorescent dye (Quant-iT PicoGreen double-stranded DNA [dsDNA] assay kit; Invitrogen), showing yields of 200 to 800 ng per sample. Qualitative analysis was done using the Agilent high-sensitivity DNA assay. High-throughput sequencing was performed by Microsynth (Balgach, Switzerland) on an Illumina NextSeq 500 platform using V2 chemistry.

RNA-seq data analysis.

RNA-seq data analysis was performed by Genostar (Montbonnot Saint Martin, France). Reads were mapped on 5,892 annotated coding sequences (CDS) of strain PA14 using CLC Genomic Workbench 7.5 software. Transcript abundance and differential-expression results between the three replicates of each sample (PA14/PJ01, PA14/PJ01ΔmexT, and PJ01/PJ01ΔmexT) were determined with the Cufflinks and Cuffdiff algorithms (48). A difference in gene expression was considered significant when the false-discovery rate (q value) was ≤0.05 and the expression ratio was ≤0.3- or ≥3.0-fold. The transcriptomic data have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (49) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE86211.

Construction of PA14-derived deletion mutants.

Single-deletion mexS, mexT, cmrA, PA2048, and mexEF-oprN mutants were constructed using overlapping PCRs and recombination events as described by Kaniga et al. (50). First, the 5′ and 3′ regions flanking mexS (417 and 433 bp, respectively), mexT (408 and 453 bp, respectively), cmrA (418 and 445 bp, respectively), PA2048 (451 and 457 bp, respectively), and mexEF-oprN (467 and 452 bp, respectively) were each amplified by PCR with specific primers (Table S5) under the following conditions: 3 min of denaturation at 98°C, followed by 30 cycles of amplification, each composed of 10 s at 98°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 30 s at 72°C, with a final extension step of 7 min at 72°C. The resultant amplicons were used as templates for overlapping PCRs with external pairs of primers to generate the mutagenic DNA fragments. The reaction mixtures contained 1× iProof high-fidelity (HF) master mix, 3% DMSO, and 0.5 μM each primer (Bio-Rad). The amplified products were cloned into plasmid pCR-Blunt according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen) and then subcloned as BamHI/XbaI fragments into the suicide vector pKNG101 in E. coli CC118λpir (50). The recombinant plasmids were next transferred to P. aeruginosa (PA14 or PJ01) by conjugation and selected on PIA containing 2,000 μg ml−1 streptomycin. The excision of undesired pKNG101 sequence was obtained by plating transformants on M9 plates containing 5% (wt/vol) sucrose. Negative selection on streptomycin was carried out to confirm the loss of the plasmid in transconjugants. The allelic exchanges were verified by PCR. Nucleotide-sequencing experiments confirmed the deletion of 826 bp in mexS, 929 bp in mexT, 997 bp in cmrA, 442 bp in PA2048, and 6,039 bp in mexEF-oprN, yielding strains P01JΔmexS, PJ01ΔmexT, PA14ΔcmrA, PJ01ΔcmrA, PJ01ΔPA2048, and PA14ΔmexEFN, respectively.

Chromosomal complementation with wild-type or mutated cmrA.

Wild-type (from PA14) and mutated (from PJ01, PJ02, PJ03, and PJ04) cmrA alleles, along with their promoter regions, were amplified by PCR by using genomic DNA as the template. The resulting amplicons, once digested with BamHI and HindIII, were inserted into linearized plasmid mini-CTX1 (51). The resultant recombinant plasmids were then transferred from E. coli CC118 to P. aeruginosa strain PA14ΔcmrA by conjugation, with subsequent selection on PIA plates supplemented with 200 μg ml−1 tetracycline to allow their chromosomal insertion into the attB site (51). Chromosomal integration of the cloned alleles was confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

Overexpression of cmrA and PA2048 from the araBAD promoter.

To study the impact of cmrA overexpression on the phenotype of P. aeruginosa, a wild-type copy of the gene was PCR amplified using specific primers (Table S5). The amplicon was cloned into vector pCR-Blunt and then subcloned as an EcoRI fragment into arabinose-inducible expression vector pJN105 (52). The new construct was introduced by electroporation into strain PA14, yielding PA14(pJN105::cmrAPA14), and selected on gentamicin at 10 μg ml−1. A positive control with the mutated allele from PJ01 [PA14(pJN105::cmrAPJ01)] and a negative control harboring pJN105 alone [PA14(pJN105)] were generated in parallel. Gene PA2048 was cloned in pJN105 under the same conditions as cmrA (see above) after amplification with specific primers (Table S5) and was then electrotransferred into PA14 to yield PA14(pJN105::PA2048). The transformants were finally analyzed for their resistance phenotypes (MICs of ciprofloxacin [CIP], chloramphenicol [CHL], and trimethoprim [TMP]) and the relative expression levels (by RT-qPCR) of genes cmrA, PA2048, and mexE in the absence and presence of the inducer arabinose (0.5%).

Construction of a bioluminescent reporter of the CmrA pathway.

To evaluate the activation of the CmrA pathway under various challenging conditions, a transcriptional fusion between gene PA2048 and the operon luxCDABE was constructed. For this, a 1,822-bp genomic fragment of strain PA14 carrying cmrA was amplified by using specific primers (Table S5). The amplicon was cloned into vector pCR-Blunt and then subcloned as an EcoRI fragment into plasmid miniCTX-lux (53). The new construct was introduced into strain PA14 by conjugation, with subsequent selection of transconjugants on PIA supplemented with 200 μg ml−1 tetracycline. In parallel, the same plasmid construct was transferred into strain PJ01 as a positive control of PA2048::lux overexpression, as this mutant constitutively produces an activated form of CmrA.

Bioluminescence induction assays.

Induction of PA2048-lux expression was measured in real time during the exponential-growth phase. Briefly, overnight cultures of luminescent strains were diluted into fresh MHB to yield an A600 of 0.01. Bacteria were incubated with shaking (250 rpm) at 37°C for 4 h (A600 = 0.1) prior to the addition of the following stressors at the indicated concentrations: ciprofloxacin (0.01 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (20 μg ml−1), trimethoprim (12 μg ml−1), diamide (8 mM), H2O2 (50 μM), paraquat (25 μM), dimethyl sulfoxide (0.5%), S-nitrosoglutathione (0.125 μg ml−1), 2-n-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline N-oxide (25 μg ml−1), glyoxal (12, 50, 100, and 200 μg ml−1), methylglyoxal (10, 50, and 100 μg ml−1), and cinnamaldehyde (70, 140, and 280 μg ml−1). The activity of the PA2048-lux fusion was monitored in white 96-well assay plates (Corning, NY), using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, WI) with the gain set at 150, read height set at 7 mm, and integration time of 1 s. In parallel, the bacterial densities were measured by their A600 in 96-well microtest plates (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). The activity of the reporter, expressed as the ratio of bioluminescence (relative light units [RLU]) to bacterial density (A600), was measured over a 6-h time course.

Killing experiments with cinnamaldehyde.

Strain PA14 and its mutants PA14ΔmexEF-oprN and PA14ΔcmrA were first rendered constitutively bioluminescent using the pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-lux-Gm plasmid as described by Damron et al. (54). Overnight cultures were then diluted into fresh MHB to yield an A600 of 0.1. Bacteria were incubated with shaking (250 rpm) at 37°C for 2.5 h (A600 = 0.8) prior to the addition of cinnamaldehyde at 1,000 μg ml−1. The bioluminescence of strains was measured as described above.

Induction of MexEF-OprN by disk diffusion tests.

The inducing activity of glyoxal (GO), methylglyoxal (MG), and cinnamaldehyde (CNA) on mexEF-oprN expression was indirectly investigated by double-disk antagonism tests with PA14 and PA14ΔmexEF-oprN on MHA. Disks loaded with 8,000 μg GO, 8,000 μg MG, or 10,000 μg CNA were deposited onto the surface of seeded MHA plates at the appropriate distance from disks containing ciprofloxacin (5 μg), chloramphenicol (1,000 μg), or trimethoprim (240 μg). Flattening of the inhibition zone around an antibiotic disk in the direction of the GO, MG, and/or CNA disk(s) was interpreted as an increase in resistance induced by the aldehyde(s).

Accession number(s).

The whole sequence of cmrA, including its 5′ UTR, is accessible through the GenBank database under accession number KX274690. The transcriptomic data of our RNA-seq experiments is accessible through the GEO database under accession number GSE86211.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Xiyu Qian for her excellent technical assistance and to Benoît Valot (UMR 6249 Chrono-Environnement, France) and Emile Van Schaftingen (Institute de Duve, Brussels, Belgium) for helpful discussions. Romé Voulhoux (LISM Marseille, France) and Eric Morello (CEPR, Tours, France) provided plasmids pJN105 and pUC18T-mini-Tn7T-lux-Gm, respectively.

This work was supported with grants from the French Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, the Vaincre la Mucoviscidose Association, and the Grégory Lemarchal Association. The French national reference center for antibiotic resistance is financed by the Ministry of Health through the Santé publique France agency.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00585-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lister PD, Wolter DJ, Hanson ND. 2009. Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin Microbiol Rev 22:582–610. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00040-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poole K, Srikumar R. 2001. Multidrug efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: components, mechanisms and clinical significance. Curr Top Med Chem 1:59–71. doi: 10.2174/1568026013395605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Köhler T, Michea-Hamzehpour M, Henze U, Gotoh N, Curty LK, Pechère JC. 1997. Characterization of MexE-MexF-OprN, a positively regulated multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 23:345–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2281594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Köhler T, Epp SF, Curty LK, Pechère JC. 1999. Characterization of MexT, the regulator of the MexE-MexF-OprN multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 181:6300–6305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li XZ, Barre N, Poole K. 2000. Influence of the MexA-MexB-OprM multidrug efflux system on expression of the MexC-MexD-OprJ and MexE-MexF-OprN multidrug efflux systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother 46:885–893. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Köhler T, van Delden C, Curty LK, Hamzehpour MM, Pechère JC. 2001. Overexpression of the MexEF-OprN multidrug efflux system affects cell-to-cell signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 183:5213–5222. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.18.5213-5222.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linares JF, Lopez JA, Camafeita E, Albar JP, Rojo F, Martinez JL. 2005. Overexpression of the multidrug efflux pumps MexCD-OprJ and MexEF-OprN is associated with a reduction of type III secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 187:1384–1391. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1384-1391.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamarche MG, Deziel E. 2011. MexEF-OprN efflux pump exports the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) precursor HHQ (4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline). PLoS One 6:e24310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin Y, Yang H, Qiao M, Jin S. 2011. MexT regulates the type III secretion system through MexS and PtrC in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 193:399–410. doi: 10.1128/JB.01079-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobel ML, Neshat S, Poole K. 2005. Mutations in PA2491 (mexS) promote MexT-dependent mexEF-oprN expression and multidrug resistance in a clinical strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 187:1246–1253. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1246-1253.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardot C, Juarez P, Jeannot K, Patry I, Plésiat P, Llanes C. 2016. Amino acid substitutions account for most MexS alterations in clinical nfxC mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2302–2310. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02622-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balasubramanian D, Schneper L, Merighi M, Smith R, Narasimhan G, Lory S, Mathee K. 2012. The regulatory repertoire of Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpC β-lactamase regulator AmpR includes virulence genes. PLoS One 7:e34067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westfall LW, Carty NL, Layland N, Kuan P, Colmer-Hamood JA, Hamood AN. 2006. mvaT mutation modifies the expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa multidrug efflux operon mexEF-oprN. FEMS Microbiol Lett 255:247–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang D, Seeve C, Pierson LS III, Pierson EA. 2013. Transcriptome profiling reveals links between ParS/ParR, MexEF-OprN, and quorum sensing in the regulation of adaptation and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Genomics 14:618. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaoui C, Overhage J, Lons D, Zimmermann A, Musken M, Bielecki P, Pustelny C, Becker T, Nimtz M, Haussler S. 2012. An orphan sensor kinase controls quinolone signal production via MexT in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 83:536–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao J, Schurr MJ, Sauer K. 2013. The MerR-like regulator BrlR confers biofilm tolerance by activating multidrug efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J Bacteriol 195:3352–3363. doi: 10.1128/JB.00318-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kallberg M, Wang H, Wang S, Peng J, Wang Z, Lu H, Xu J. 2012. Template-based protein structure modeling using the RaptorX Web server. Nat Protoc 7:1511–1522. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winsor GL, Griffiths EJ, Lo R, Dhillon BK, Shay JA, Brinkman FS. 2016. Enhanced annotations and features for comparing thousands of Pseudomonas genomes in the Pseudomonas genome database. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D646–D653. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz S, Eckweiler D, Bielecka A, Nicolai T, Franke R, Dotsch A, Hornischer K, Bruchmann S, Duvel J, Haussler S. 2015. Elucidation of sigma factor-associated networks in Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals a modular architecture with limited and function-specific crosstalk. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004744. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian ZX, Fargier E, Mac Aogain M, Adams C, Wang YP, O'Gara F. 2009. Transcriptome profiling defines a novel regulon modulated by the LysR-type transcriptional regulator MexT in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res 37:7546–7559. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai J, Salmon K, DuBow MS. 1998. A chromosomal ars operon homologue of Pseudomonas aeruginosa confers increased resistance to arsenic and antimony in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 144:2705–2713. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-10-2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook CE, Bergman MT, Finn RD, Cochrane G, Birney E, Apweiler R. 2016. The European Bioinformatics Institute in 2016: data growth and integration. Nucleic Acids Res 44(D1):D20–D26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wasinger VC, Humphery-Smith I. 1998. Small genes/gene-products in Escherichia coli K-12. FEMS Microbiol Lett 169:375–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams MA, Jia Z. 2005. Structural and biochemical evidence for an enzymatic quinone redox cycle in Escherichia coli: identification of a novel quinol monooxygenase. J Biol Chem 280:8358–8363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Revington M, Semesi A, Yee A, Shaw GS. 2005. Solution structure of the Escherichia coli protein YdhR: a putative mono-oxygenase. Protein Sci 14:3115–3120. doi: 10.1110/ps.051809305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams MA, Jia Z. 2006. Modulator of drug activity B from Escherichia coli: crystal structure of a prokaryotic homologue of DT-diaphorase. J Mol Biol 359:455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Portnoy VA, Herrgard MJ, Palsson BO. 2008. Aerobic fermentation of D-glucose by an evolved cytochrome oxidase-deficient Escherichia coli strain. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:7561–7569. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00880-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fargier E, Mac Aogain M, Mooij MJ, Woods DF, Morrissey JP, Dobson AD, Adams C, O'Gara F. 2012. MexT functions as a redox-responsive regulator modulating disulfide stress resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 194:3502–3511. doi: 10.1128/JB.06632-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fetar H, Gilmour C, Klinoski R, Daigle DM, Dean CR, Poole K. 2011. mexEF-oprN multidrug efflux operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: regulation by the MexT activator in response to nitrosative stress and chloramphenicol. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:508–514. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00830-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee C, Kim I, Lee J, Lee KL, Min B, Park C. 2010. Transcriptional activation of the aldehyde reductase YqhD by YqhC and its implication in glyoxal metabolism of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 192:4205–4214. doi: 10.1128/JB.01127-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Visvalingam J, Hernandez-Doria JD, Holley RA. 2013. Examination of the genome-wide transcriptional response of Escherichia coli O157:H7 to cinnamaldehyde exposure. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:942–950. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02767-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kosmachevskaya OV, Shumaev KB, Topunov AF. 2015. Carbonyl stress in bacteria: causes and consequences. Biochemistry (Mosc) 80:1655–1671. doi: 10.1134/S0006297915130039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee C, Park C. 2017. Bacterial responses to glyoxal and methylglyoxal: reactive electrophilic species. Int J Mol Sci 18:E169. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groeger AL, Freeman BA. 2010. Signaling actions of electrophiles: anti-inflammatory therapeutic candidates. Mol Interv 10:39–50. doi: 10.1124/mi.10.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacLean MJ, Ness LS, Ferguson GP, Booth IR. 1998. The role of glyoxalase I in the detoxification of methylglyoxal and in the activation of the KefB K+ efflux system in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 27:563–571. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sukdeo N, Honek JF. 2007. Pseudomonas aeruginosa contains multiple glyoxalase I-encoding genes from both metal activation classes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1774:756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner PC, Miller EN, Jarboe LR, Baggett CL, Shanmugam KT, Ingram LO. 2011. YqhC regulates transcription of the adjacent Escherichia coli genes yqhD and dkgA that are involved in furfural tolerance. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 38:431–439. doi: 10.1007/s10295-010-0787-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mousavi F, Bojko B, Bessonneau V, Pawliszyn J. 2016. Cinnamaldehyde characterization as an antibacterial agent toward E. coli metabolic profile using 96-blade solid-phase microextraction coupled to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res 15:963–975. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Utchariyakiat I, Surassmo S, Jaturanpinyo M, Khuntayaporn P, Chomnawang MT. 2016. Efficacy of cinnamon bark oil and cinnamaldehyde on anti-multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the synergistic effects in combination with other antimicrobial agents. BMC Complement Altern Med 16:158. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1134-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ditta G, Stanfield S, Corbin D, Helinski DR. 1980. Broad host range DNA cloning system for Gram-negative bacteria: construction of a gene bank of Rhizobium meliloti. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77:7347–7351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard, 10th ed CLSI document M07-A10. CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2015. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests, approved standard, 12th ed CLSI document M02-A12. CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vasseur P, Soscia C, Voulhoux R, Filloux A. 2007. PelC is a Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane lipoprotein of the OMA family of proteins involved in exopolysaccharide transport. Biochimie 89:903–915. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Köhler T, Curty LK, Barja F, van Delden C, Pechère JC. 2000. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on cell-to-cell signaling and requires flagella and pili. J Bacteriol 182:5990–5996. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.21.5990-5996.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Essar DW, Eberly L, Hadero A, Crawford IP. 1990. Identification and characterization of genes for a second anthranilate synthase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: interchangeability of the two anthranilate synthases and evolutionary implications. J Bacteriol 172:884–900. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.884-900.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dumas JL, van Delden C, Perron K, Köhler T. 2006. Analysis of antibiotic resistance gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by quantitative real-time-PCR. FEMS Microbiol Lett 254:217–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, Rozen SG. 2012. Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 40:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang D, Qi M, Calla B, Korban SS, Clough SJ, Cock PJ, Sundin GW, Toth I, Zhao Y. 2012. Genome-wide identification of genes regulated by the Rcs phosphorelay system in Erwinia amylovora. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 25:6–17. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-08-11-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. 2002. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res 30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaniga K, Delor I, Cornelis GR. 1991. A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in Gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene 109:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoang TT, Kutchma AJ, Becher A, Schweizer HP. 2000. Integration-proficient plasmids for Pseudomonas aeruginosa: site-specific integration and use for engineering of reporter and expression strains. Plasmid 43:59–72. doi: 10.1006/plas.1999.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newman JR, Fuqua C. 1999. Broad-host-range expression vectors that carry the L-arabinose-inducible Escherichia coli araBAD promoter and the araC regulator. Gene 227:197–203. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Becher A, Schweizer HP. 2000. Integration-proficient Pseudomonas aeruginosa vectors for isolation of single-copy chromosomal lacZ and lux gene fusions. Biotechniques 29:948–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Damron FH, McKenney ES, Barbier M, Liechti GW, Schweizer HP, Goldberg JB. 2013. Construction of mobilizable mini-Tn7 vectors for bioluminescent detection of Gram-negative bacteria and single-copy promoter lux reporter analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:4149–4153. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00640-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.