ABSTRACT

Albitiazolium is the lead compound of bisthiazolium choline analogues and exerts powerful in vitro and in vivo antimalarial activities. Here we provide new insight into the fate of albitiazolium in vivo in mice and how it exerts its pharmacological activity. We show that the drug exhibits rapid and potent activity and has very favorable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Pharmacokinetic studies in Plasmodium vinckei-infected mice indicated that albitiazolium rapidly and specifically accumulates to a great extent (cellular accumulation ratio, >150) in infected erythrocytes. Unexpectedly, plasma concentrations and the area under concentration-time curves increased by 15% and 69% when mice were infected at 0.9% and 8.9% parasitemia, respectively. Albitiazolium that had accumulated in infected erythrocytes and in the spleen was released into the plasma, where it was then available for another round of pharmacological activity. This recycling of the accumulated drug, after the rupture of the infected erythrocytes, likely extends its pharmacological effect. We also established a new viability assay in the P. vinckei-infected mouse model to discriminate between fast- and slow-acting antimalarials. We found that albitiazolium impaired parasite viability in less than 6 and 3 h at the ring and late stages, respectively, while parasite morphology was affected more belatedly. This highlights that viability and morphology are two parameters that can be differentially affected by a drug treatment, an element that should be taken into account when screening new antimalarial drugs.

KEYWORDS: antimalarial activity, antimalarial agents, malaria, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, pharmacology

INTRODUCTION

Malaria remains one of the major human infectious diseases, with more than 40% of the world's population being at risk, and is responsible for 150 million to 300 million annual clinical cases and about 430,000 deaths, most of which occur in children under 5 years old and in sub-Saharan Africa (1). In the absence of a marketed vaccine and in the face of the recent emergence of resistance to the artemisinin derivatives, the need for new antimalarial drugs has never been greater. These new drugs must be structurally unrelated to existing antimalarials and should have a new mechanism of action (1, 2).

In this context, our laboratories have developed a new class of antimalarial drugs that target membrane biogenesis in Plasmodium falciparum, the most lethal malaria-causing parasite, during its intraerythrocytic development. During its blood stage, Plasmodium synthesizes considerable amounts of membranes for its growth and proliferation. The lipid composition of these membranes differs from that of membranes of the host. Cholesterol is almost completely absent, while phospholipids with phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine constitute the bulk of malarial lipids (3–5). We designed and developed compounds whose structures mimic the structure of choline in order to target choline metabolism and thus prevent the PC biosynthesis that is essential for Plasmodium during the asexual blood stage. Over the past few years, compounds were optimized for in vitro antimalarial activity (6–8), leading to bisthiazolium salts which inhibit P. falciparum asexual blood stages at concentrations in the low-nanomolar range (9, 10). These compounds are also able to cure in vivo malaria infections at very low doses in rodent (<1 mg/kg of body weight by the intraperitoneal [i.p.] route) and primate models (10). The lead compound albitiazolium (formerly named T3 and SAR97276) (Fig. 1) (10) was successfully evaluated during absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination (ADME) preclinical studies and human phase I and phase II clinical trials. Due to the absence of an oral formulation to treat uncomplicated malaria, albitiazolium was developed by Sanofi for the treatment of severe malaria by the intramuscular route. After successful phase II trials in adult patients, trials in a pediatric population revealed higher drug clearance in children than in adults without a significant change in the highest (maximum) observed concentration (Cmax). The high Cmax value did not allow the dose to be increased without risking potential toxic effects. This constraint stopped the clinical development of albitiazolium. Nevertheless, understanding the mode of action of this drug is of utmost interest for future developments.

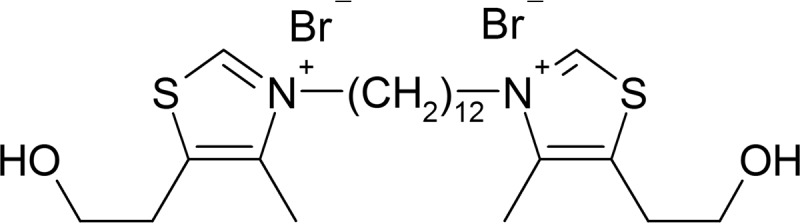

FIG 1.

Structure of the bisthiazolium salt albitiazolium. Albitiazolium has potent activity against the in vitro growth of P. falciparum with an IC50 of 2.3 nM (10).

The bisthiazolium salts exert their antimalarial activity through inhibition of de novo PC biosynthesis by blocking the parasite choline carrier (10–12). An additional interaction with heme inside the food vacuole contributes to the antimalarial activity (13). The impressive potency and specificity of these dual effectors are likely due to their ability to accumulate several hundredfold in a nonreversible way in P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Drug accumulation in in vitro cultures is so significant that it depletes the incubation medium of drug. Accumulation is restricted to infected erythrocytes, and the major part of the accumulated drug is found in the intraerythrocytic parasite (10, 13, 14).

We observed that albitiazolium (by contact for less than 2 h at 80 nM) rapidly and irreversibly affects P. falciparum viability and condemns the parasite to death before the end of the cycle (15). However, morphological changes and the arrest of cell cycle progression are apparent only at the late trophozoite stage (11, 15). Here, we conducted in vivo studies in P. vinckei-infected mice to quantify the level of accumulation in infected erythrocytes and to analyze whether this is accompanied by depletion of albitiazolium from plasma. The results demonstrated that massive accumulation also occurs in vivo in P. vinckei-infected mice and showed unexpected pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties of this choline analogue, revealing that plasma concentrations increase with the degree of parasitemia. This unique property is likely due to the release of the drug from the infected erythrocytes into the plasma, leading to the recycling of pharmacologically active albitiazolium and a subsequent extension of its pharmacological activity.

The dissociation between the pharmacological effect and the effect on parasitemia was measured using a new in vivo viability assay. This led us to conclude that albitiazolium exerts its pharmacological activity through a Trojan horse effect leading to the rapid reduction of parasite viability as a consequence of high cytotoxic drug activity.

RESULTS

Pharmacokinetics of albitiazolium in healthy and P. vinckei-infected mice.

The goal of this study was to investigate the PK and PD properties of albitiazolium in a murine malaria model following the administration of a single dose of the choline analogue to the mouse. The capacity for choline analogues to clear high parasitemia in mice (10) incited us to perform these experiments at both moderate and high parasitemias using a dose able to cure both levels of infection. Control groups (n = 4) and two groups of P. vinckei-infected mice with 0.9% ± 0.29% and 8.9% ± 1.92% parasitemia (n = 9) thus received a single i.p. administration of 3.7 mg/kg albitiazolium. The erythrocyte fraction collected from mice was composed of either red blood cells (RBC) (control mice) or both RBC and infected red blood cells (IRBC) (infected mice).

Albitiazolium plasma concentrations are increased in infected mice.

The plasma, RBC, and IRBC concentration-time curves were modeled according to a two-compartment model (Fig. 2A and B). The PK parameters are presented in Table 1. Following albitiazolium administration, similar Cmax values of ∼8 μM were found in the plasma of the three groups of mice. Plasma concentrations and the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC), however, increased with the level of parasitemia in P. vinckei-infected mice. This increase was more important at a high parasitemia (Fig. 2A and Table 1). In uninfected mice, the albitiazolium concentration was below the limit of quantification after 12 h, but it was measurable for up to 24 h and 36 h in mice with 0.9% and 8.9% parasitemia, respectively (Fig. 2A). In addition, the terminal elimination half-lives (t1/2 elim) in the infected mice were significantly longer. The AUC ratios (AUC for infected mice/AUC for uninfected mice) of plasma indicated an increase in the AUC of 15% and 69% for mice with 0.9% and 8.9% parasitemia, respectively, compared to that for uninfected mice. In plasma, the total clearance (CL/F) decreased with the increase in the level of parasitemia.

FIG 2.

Pharmacokinetic study of albitiazolium in healthy and P. vinckei-infected mice. (A to E) Albitiazolium concentration-versus-time curves after administration of a single 3.74-mg/kg dose i.p. Concentrations in the plasma (A), RBC or IRBC (B), liver (C), heart (D), and brain (E) of healthy mice or P. vinckei-infected mice at 0.9% and 8.9% parasitemia are given as means ± SDs (n = 3). All concentrations were determined until 35 h after albitiazolium administration. Data not shown on the graph(s) were below the analytical limit of quantitation (3.63 nM in plasma, 7.26 nM in RBC, 7.26 nmol/kg in brain, and 72.6 nmol/kg in liver and heart). (F) Follow-up of parasitemia in mice treated (closed symbols) or not treated (open symbols) with 3.74 mg/kg albitiazolium. Treatment was started when infected mice had an initial parasitemia of 0.9% (▲, △) or 8.9% (●, ○). Values are given as means ± SEMs (n ≥ 3).

TABLE 1.

PK parameters in blood after i.p. administration of 3.74 mg/kg (8.2 μmol/kg) albitiazoliuma

| Group and compartment | Cmax (μM) | Tmax (h) | AUC0–inf (μmol · h/liter) | AUC ratiob | t1/2 elim (h) | CL/F (liters/h/kg) | V/F (liters/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninfected mice | |||||||

| RBC | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 7.9 | |||

| Plasma | 8.05 | 0.083 | 2.49 | 4.52 | 3.3 | 21.5 | |

| Mice with 0.9% parasitemia | |||||||

| RBC + IRBC | 0.86 | 0.083 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 8.01 | ||

| IRBC | 64.24 | 0.083 | 190.74 | 335 | 8.72 | ||

| Plasma | 8.73 | 0.083 | 2.86 | 1.15 | 9.05 | 2.84 | 37.1 |

| Mice with 8.9% parasitemia | |||||||

| RBC + IRBC | 3.48 | 0.5 | 11.73 | 20.6 | 8.8 | ||

| IRBC | 39.82 | 0.5 | 188.54 | 331 | 37.7 | ||

| Plasma | 8.22 | 0.083 | 4.2 | 1.69 | 8.8 | 1.95 | 24.7 |

Cmax, the highest (maximum) observed concentration; Tmax, the time to Cmax relative to the time of dosing; AUC0–inf, total area under the concentration-time curves from time zero to infinity; t1/2 elim, elimination half-life; CL/F, total clearance; V/F, steady-state volume of distribution.

The AUC ratio is the AUC for infected mice/AUC for uninfected mice.

Albitiazolium accumulates in infected erythrocytes.

Uninfected erythrocytes do not accumulate albitiazolium. Following albitiazolium administration in uninfected mice, the Cmax value in RBC was 0.35 μM after 15 min (Table 1), while at the same time, the plasma concentration was 5 μM. Thus, the cellular accumulation ratio (CAR), i.e., the ratio of the intracellular concentration in RBC to the plasma concentration, was below 1 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

The AUC for the erythrocyte fraction increased from 0.57 μmol · h/liter in healthy mice to 1.9 and 11.7 μmol · h/liter in infected mice with 0.9% and 8.9% parasitemia, respectively. The AUCs for IRBC (AUCIRBC) in both mice with 0.9% parasitemia and mice with 8.9% parasitemia were largely increased compared to the AUC for RBC (AUCRBC) in healthy mice. The AUCIRBC (deduced from the AUCIRBC plus the AUCRBC [AUCRBC + IRBC] but corrected for the contribution from uninfected erythrocytes) were 187 to 190 μmol · h/liter; i.e., they were remarkably similar in both infected mice with 0.9% parasitemia and infected mice with 8.9% parasitemia (Table 1). The ratios of the albitiazolium content of IRBC to that of RBC (AUCIRBC/AUCRBC) were 335 and 331 for mice with 0.9% and 8.9% parasitemias, respectively; i.e., they were also very similar (Fig. 2B and Table 1).

Remarkably, in both infected groups, the CAR in the IRBC was very high, indicating an important accumulation of albitiazolium in IRBC (Fig. S1). The CAR increased until 4 h after drug administration, with maximal values of 527 ± 126 at a low parasitemia and 145 ± 14 at a high parasitemia (Fig. S1). Considering that the concentrations of albitiazolium in IRBC in infected mice with low and high levels of parasitemia were comparable (Fig. 2B), the difference in the CAR values was mainly attributed to the albitiazolium concentration in the plasma of the two groups of infected mice (Fig. 2A).

Tissue distribution of albitiazolium.

Albitiazolium was widely distributed throughout the major organs, with high concentrations being found in liver and heart tissue but not in brain in both healthy and infected mice (Fig. 2C to E). Maximum concentrations in tissue for the three organs were obtained at between 30 min and 1 h after administration. For the liver, a decrease in the AUC in the infected mice compared to the healthy mice was observed and was dependent on the level of parasitemia (Fig. 2C and Table 2). The ratios of the AUC for the liver/AUC for plasma were 38 in healthy mice, 29 in infected mice with 0.9% parasitemia, and 10 in infected mice with 8.9% parasitemia. In heart tissue, similar concentrations were observed in all three groups of mice, the concentrations remained relatively stable over the 35-h study period, and the elimination half-life was very high (>100 h) (Fig. 2D). For the brain, the AUC in infected mice was higher than that in healthy mice (Fig. 2E and Table 2). However, the ratios of the AUC for the brain/AUC for plasma were 0.39, 0.46, and 0.52 in healthy mice and infected mice with 0.9% and 8.9% parasitemia, respectively, demonstrating that albitiazolium uptake in the brain is very low.

TABLE 2.

PK parameters in tissuesa

| Group | AUC0–inf (μmol · h/kg) |

t1/2 elim (h) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Brain | Heart | Liver | Brain | |

| Uninfected mice | 93.5 | 0.98 | 220b | 9 | 4.91 |

| Mice with 0.9% parasitemia | 82.5 | 1.32 | 262b | 14.3 | 10.8 |

| Mice with 8.9% parasitemia | 42 | 2.19 | 204b | 11.5 | 8 |

AUC0–inf, total area under the concentration-time curves from time zero to infinity; t1/2 elim, elimination half-life.

Data represent the AUC from time zero to 35 h.

Effect of albitiazolium administration on parasitemia.

Simultaneously, we determined the levels of parasitemia in all infected mice treated or not treated with albitiazolium. At a 0.9% initial parasitemia, the parasitemia rose to 13.8% ± 2.2% at 35 h in control mice, while albitiazolium treatment decreased the parasitemia to 0.42% ± 0.08% (Fig. 2F). At an 8.9% initial parasitemia, the treatment induced a decrease in parasitemia from 6 h on; at 35 h, the parasitemia was 2.4% ± 0.3%, whereas it was 47.3% ± 4.6% in the untreated mice (Fig. 2F).

When the results are taken together, this first set of experiments showed that the high level of accumulation of albitiazolium in IRBC also occurred in vivo and, most interestingly, that the PK profiles in plasma were different in healthy and infected mice, with the plasmatic AUCs being substantially increased in mice with high parasitemia.

The albitiazolium contained in treated P. vinckei-infected RBC is released into the plasma.

The increased albitiazolium concentration in the plasma of infected mice could be due to a release of the accumulated drug from IRBC or, alternatively, to a lower level of drug uptake in the liver. The first case would constitute the recycling of the albitiazolium that had accumulated in IRBC. We investigated this hypothesis by comparing plasma concentrations when equal doses of albitiazolium were injected intravenously (i.v.) either as a saline solution or in the form of loaded IRBC. In the latter case, the albitiazolium recovered in the plasma must have been released from loaded IRBC.

In two concomitant but independent experiments, [14C]albitiazolium was administered intravenously to healthy mice at 0.15 and 0.09 mg/kg, either directly in the blood circulation as a saline solution or after [14C]albitiazolium was allowed to accumulate within IRBC collected from a set of infected mice. Albitiazolium was then quantified in the different RBC compartments, plasma, and spleen at different time points after injection.

When [14C]albitiazolium was injected directly into the blood circulation, a classical plasma concentration-time curve was observed (Fig. 3), with the profile being similar to the one determined by liquid chromatography (LC)-mass spectrometry (MS) in the PK/PD experiment described above (Fig. 2A). When data were normalized with respect to the injected dose, similar plasma Cmax values were found. Trace levels of albitiazolium were found in RBC (Fig. 3B), while the concentrations in the liver were relatively high (Table 3) and corresponded to those detected in the PK/PD study (Table 2) after normalization (not shown). Concentrations in the spleen were very low and did not exceed 0.2 μmol/kg (Fig. 3C and Table 3).

FIG 3.

Comparative fate of albitiazolium after administration of [14C]albitiazolium in saline solution or loaded in P. vinckei-infected RBC to healthy mice. Naive mice received by the intravenous route 0.15 mg/kg of [14C]albitiazolium either in 0.9% NaCl (▲) or loaded in IRBC (□). At different time points after the injection, mice were sacrificed and plasma (A), RBC or RBC plus IRBC (B), and spleen (C) were collected and the albitiazolium concentration was determined. The data presented are from one representative experiment and are expressed as means ± SEMs (n = 3).

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters after administration of albitiazolium directly in the blood circulation in saline solution or after being accumulated within IRBCa

| Dose injected (mg/kg)b | Compartment | Saline solution |

Loaded IRBC |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmaxc | Tmax (h) | AUCd | Cmaxc | Tmax (h) | AUCd | ||

| 0.15 | (I)RBC | 0.059 | 0.017 | 0.51 | 3.91 | 0.083 | 28.21 |

| Plasma | 1.27 | 0.017 | 0.64 | 0.33 | 0.083 | 1.92 | |

| 0.09 | (I)RBC | 0.018 | 0.5 | blq | 1.326 | 0.25 | 5.00 |

| Plasma | 0.117 | 0.083 | 0.40 | 0.221 | 0.083 | 0.64 | |

| 0.15 | Spleen | 0. 2 | 0.017 | 13 | 2.1 | 1 | 269 |

| Liver | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 0.09 | Spleen | 0. 04 | 0.083 | 1 | 2.5 | 2 | 193 |

| Liver | 2.2 | 0.5 | 17 | 1.5 | 2 | 21 | |

Cmax, the highest (maximum) observed concentration; Tmax, the time to Cmax relative to the time of dosing; AUC, area under the concentration-time curve; (I)RBC, RBC plus IRBC; ND, not determined; blq, below the limit of quantification.

A dose of 0.15 mg/kg corresponds to 0.33 μmol/kg, and a dose of 0.09 mg/kg corresponds to 0.2 μmol/kg.

Units for Cmax are micromolar for (I)RBC and plasma and micromoles per kilogram of tissue for spleen and liver.

Units for AUC are micromoles · hour per liter for (I)RBC and plasma and micromoles · hour per kilogram of tissue for spleen and liver.

When [14C]albitiazolium-loaded IRBC were injected, substantial amounts of drug were detected in the plasma, and the kinetic profile suggested a continuous and progressive release of the radioactive drug from IRBC. The plasma level of albitiazolium remained very high over time compared to that when albitiazolium was injected in saline solution (Fig. 3A). With [14C]albitiazolium-loaded IRBC (Fig. 3A), an AUC increase of 3 and 1.6 times was observed after administration of 0.15 and 0.09 mg/kg, respectively, compared to that after injection of the drug in saline solution (Table 3). We observed a concomitant decrease in albitiazolium levels in the total erythrocyte compartment (RBC plus IRBC) (Fig. 3B). The spleen, whose function is to remove infected or damaged cells from the circulation, showed a rapid and important increase in the albitiazolium concentration in less than 3 h. The Cmax (2.1 to 2.5 pmol/mg) was 10 times higher than that after administration of similar doses in saline solution (Fig. 3C and Table 3). This strong increase in drug concentration in the spleen likely reflects the capture and/or destruction of the loaded IRBC. The spleen AUC was 20 and 193 times higher for doses of 0.15 and 0.09 mg/kg, respectively, after injection of [14C]albitiazolium-loaded IRBC than after injection in saline solution (Table 3). No significant difference in Cmax and AUC in the liver was observed when albitiazolium was injected in saline solution and when loaded IRBC were administered (Table 3).

The released albitiazolium is pharmacologically active.

The detection of substantial quantities of drug in plasma after administration of IRBC loaded with [14C]albitiazolium indicated that plasma can be supplied with the albitiazolium released from loaded IRBC (Fig. 3A), but is this recycled albitiazolium still pharmacologically active? The degradation or metabolism of albitiazolium has never been observed in IRBC, and albitiazolium is only weakly bound by human plasma proteins (33% at 20 ng/ml) (unpublished observations), suggesting that the drug remains active. Also, a part of the accumulated albitiazolium is strongly bound to hemozoin (13), which could prevent drug activity.

We thus investigated the pharmacological activity of the released albitiazolium by measuring its capacity to block the proliferation of P. vinckei-infected RBC injected into naive mice. Three groups of mice received IRBC loaded with 0.14, 0.15, or 0.18 mg/kg albitiazolium. Their plasma was collected, and the released albitiazolium content was quantified. These plasma samples were mixed with fresh P. vinckei-infected RBC suspensions (10% hematocrit), resulting in final albitiazolium concentrations of 315, 404, and 395 nM, respectively. Albitiazolium-free plasma served as a control. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, the treated IRBC were injected into naive mice and the development of parasitemia was followed. The level of parasitemia was strongly reduced (by 48% ± 3%, mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] for the three batches after 1 day) compared to that in the control, indicating that the albitiazolium released from IRBC still affected parasite viability and was at least partially pharmacologically active (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Evolution of parasitemia in mice infected with P. vinckei-infected RBC pretreated with plasma containing released albitiazolium. Mice received 0.14 mg/kg (A), 0.15 mg/kg (B), or 0.18 mg/kg (C) of albitiazolium injected as loaded IRBC. After 15 min, plasma was collected and the concentration of released albitiazolium was determined. Then, a new batch of 108 P. vinckei-infected RBC was incubated for 1 h at 37°C in the presence of naive plasma or of collected plasma containing 315 nM (A), 404 nM (B), or 395 nM (C) released albitiazolium. These parasite preparations were then injected intravenously into healthy mice, and the development of parasitemia was followed by the performance of thin blood smears. The level of parasitemia was expressed as a percentage of that for the control, and data are means ± SEMs (n = 3).

In vivo albitiazolium treatment induces a rapid loss of P. vinckei parasite viability.

In P. falciparum in vitro cultures, the accumulation of albitiazolium in the intraerythrocytic parasite has been shown to be a rapid process that requires less than 2 h to reach steady state (14) and that is associated with a rapid irreversible toxic effect. However, morphological alterations and the destruction of the parasite were observed only much later (15). It is difficult to extrapolate in vitro PD data to in vivo models because both the PK and PD properties of the compound must be considered. However, morphological alterations of parasites also seem to be delayed in vivo, since we observed that after albitiazolium administration to P. vinckei-infected mice (PK/PD study), the parasitemia did not decrease until 6 h after the treatment (Fig. 2F). In order to determine whether albitiazolium acts as rapidly in vivo, we designed and validated a test that measures the viability of circulating parasites in mice treated with albitiazolium. IRBC taken from infected and treated mice at different times after treatment were washed and then transferred to healthy mice. The viability of the transferred parasites was assessed by their ability to proliferate and was deduced from the parasite multiplication rate (PMR) over a 24-h period (the P. vinckei life cycle time). The PMR method has been validated in independent experiments conducted with untreated infected mice, where the development of parasitemia to levels of between 1 and 30% was linear and the PMR appeared to be constant. Analysis of the parasitemia profile in the recipient mice allowed the number of initially injected infectious parasites to be traced back. Simultaneously, the parasitemia was determined by counting unaltered parasites on Giemsa-stained thin blood smears.

In a first experiment, two groups of P. vinckei-infected mice received 7. 4 mg/kg albitiazolium (7 times the efficient dose required to decrease the level of parasitemia by 50% [ED50]) when the synchronously growing parasites were either in the ring stage or, 12 h later, in mature stages. Analysis of thin blood smears did not reveal a significant decrease in parasitemia until 12 h after drug administration for both groups. Then, the parasitemia slowly decreased to ∼15% of that for the control 12 h later (Fig. 5A). On the contrary, the viability test revealed a very rapid and drastic effect for both treatments. When mice were treated with albitiazolium at the ring stage, the number of viable parasites decreased by 22.4% after 3 h and by 99.93% after 6 h and did not decrease further thereafter (Fig. 5B). When mice were treated at the mature stages, viability was affected even faster, decreasing by 43.6% after only 10 min of treatment and by 99.98% after 3 h, again, without a further decrease thereafter (Fig. 5C).

FIG 5.

Comparative effect of albitiazolium on parasitemia and on parasite viability in mice. (A) Follow-up of parasitemia in donor mice in the absence of treatment (■) or after administration of 7.4 mg/kg albitiazolium at the ring (▲) and mature (▼) stages. (B and C) Follow-up of the number of parasites in the donor mouse treated at the ring (B) or mature (C) stages. The number of visible parasites per mouse was determined by counting thin blood smears (open symbols and dotted lines). The number of viable parasites (closed symbols and solid lines) was experimentally determined by measuring their capacity to proliferate in a second set of mice (recipient mice) (untreated [■, □], treated at the ring stage [▲, △], treated at mature stages (▼, ▽). (D) Follow-up of parasitemia of untreated donor mice (■) or donor mice treated with 7.4 mg/kg albitiazolium (●) or 7.4 and then 3.7 mg/kg albitiazolium (◆) at mature stages. (E) Number of visible (open symbols and dotted lines) and viable (closed symbols and solid lines) parasites per mouse after no treatment (■, □), one administration (●, ○), or two administrations (◆, ♢) of albitiazolium. For all experiments, two mice per time point were used. Arrows in panels D and E, times of albitiazolium administration.

It can thus be concluded that albitiazolium exerts its toxic effect on 99.9% of parasites very rapidly, in less than 6 h at the ring stage and in less than 3 h at the mature stages. The fact that there was no further decline in the level of parasite viability beyond this time indicates that at least one additional albitiazolium administration would be required to kill the 2.4 × 105 to 5 × 105 parasites that escaped the first dose.

We therefore monitored the effect of a second dose of albitiazolium given 12 h after administration of the first dose. The first dose showed the same delayed effect on morphology and very rapid irreversible toxicity (Fig. 5D and E). The second dose again eliminated 99.9% of the remaining very low number of viable parasites in less than 2 h (Fig. 5E), reducing the total number of viable parasites to less than 650 per mouse.

A highly sensitive assay confirms that albitiazolium treatment also rapidly affects parasite viability in vitro.

Considering the difference between the very rapid effect on parasite viability and the delayed appearance of morphological alterations in treated mice, we analyzed this phenomenon in vitro with P. falciparum parasites. The number of viable parasites after treatment was determined using an assay recently described by Sanz et al. (16). This method is based on serial parasite dilutions and shows a higher sensitivity than the direct incorporation of [3H]hypoxanthine in parasite cultures.

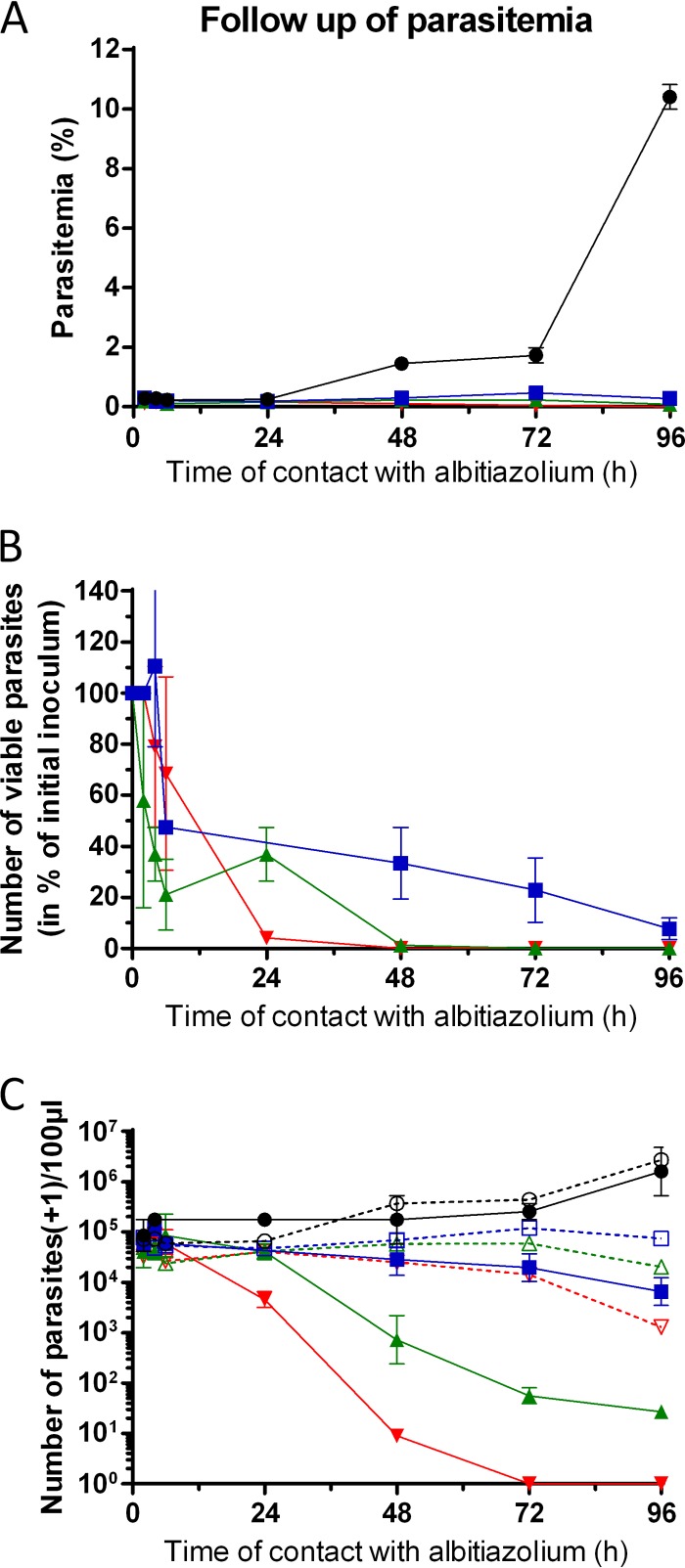

Similar to the effects observed with P. vinckei in mice, the P. falciparum morphology was affected late. After one developmental cycle (48 h), the level of parasitemia decreased by 80% for all albitiazolium concentrations. After 96 h, the decreases in parasitemia were 97%, 99%, and 99.98% for albitiazolium concentrations of 3×, 10×, and 100× the concentration required to inhibit parasite viability by 50% (IC50), respectively (Fig. 6A). On the other hand, the viability assay revealed that parasites were rapidly affected (Fig. 6B and C). After only 6 h, the number of viable parasites had already decreased by 50%, 79%, and 72% for albitiazolium concentrations of 3×, 10×, and 100× IC50, respectively. After 48 h, parasite viability was reduced by 67%, 98.8%, and ≥99.99% for albitiazolium concentrations of 3×, 10×, and 100× IC50, respectively, while the number of untreated parasites tripled (Fig. 6B and C). Finally, after 96 h P. falciparum viability was reduced by 92%, 99.98%, and 100% for albitiazolium concentrations of 3×, 10×, and 100× IC50, respectively, reflecting continuous drug action over time (Fig. 6B).

FIG 6.

Effect of albitiazolium on P. falciparum parasite viability. The study was carried out in the context of the paper of Sanz et al. (16). (A) Follow-up of parasitemia of untreated cultures (●) or cultures treated with an albitiazolium concentration corresponding to 3× (■), 10× (▲), or 100× (▼) its IC50. (B) Effect of albitiazolium on parasite viability, expressed as a percentage of the initial inoculum. (C) Follow-up of the number of parasites per 100 μl of culture. The number of visible parasites per 100 μl (open symbols and dotted lines) was determined by counting the number of parasites in thin blood smears of treated or untreated cultures. The number of viable parasites (closed symbols and solid lines) was calculated using serial dilutions of treated or untreated cultures. Results are expressed as means ± SEMs (n = 3) of one representative experiment.

DISCUSSION

In P. falciparum in vitro cultures, the massive accumulation of albitiazolium in infected erythrocytes results in a concomitant depletion of the drug from the incubation medium. In infected patients, the consequence could be an extremely short in vivo half-life of the drug or low plasma concentrations. We thus investigated the fate of albitiazolium in vivo in the P. vinckei-infected mouse model.

As was observed in vitro in P. falciparum, albitiazolium rapidly and massively accumulated in P. vinckei-infected erythrocytes in vivo, while no accumulation was observed in uninfected erythrocytes (Fig. 2; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This massive accumulation, however, did not lead to albitiazolium depletion in plasma. Unexpectedly, albitiazolium plasma concentrations and the plasma AUC significantly increased with the level of parasitemia and the total drug clearance decreased (Table 1 and Fig. 2). These results suggest that the plasma level of albitiazolium in infected humans would be similar to or even higher than (depending on the level of parasitemia) that in healthy subjects. Data obtained during phase I and II clinical trials showed that there was no albitiazolium depletion from the plasma in P. falciparum-infected patients. PK profiles were similar between patients and healthy subjects, except for a longer half-life in the plasma of patients (Sanofi, unpublished data). This extended elimination half-life was also observed in mice (Table 1). These results indicate that the P. vinckei mouse model is reliable for exploring the PK/PD profiles of new antimalarials even if we must keep in mind the shorter life cycle duration of P. vinckei.

There was a rapid and high level of uptake of albitiazolium in liver and heart (Fig. 2C and D). It is noteworthy that albitiazolium concentrations in heart tissue remained relatively stable during the 35 h of the study. These high concentrations likely reflect a rapid uptake of the drug when plasma concentrations are high, followed by a slow release of the drug into the plasma (Fig. 2C and D and 7). Given that, at 35 h, the plasma concentrations were low or even below the limit of quantification, the elimination rate of albitiazolium from the body was thus likely controlled by the slow release of the drug from the heart tissue. In contrast, there was a low level of uptake of albitiazolium in the brain even at high plasma concentrations (Fig. 2E and 7 and Table 1). The slight increase in the brain AUC with the level of parasitemia may be due to the presence/sequestration of IRBC in the blood capillaries.

FIG 7.

Schematic representation of the distribution and fate of albitiazolium in noninfected and P. vinckei-infected mice. The level of exposure of the mice to albitiazolium is represented by the AUC. The AUCs for plasma, RBC, and IRBC are in micromoles · hour per liter. The AUCs for organ tissues are in micromoles · hours per kilogram. *, the AUC for the spleen was obtained after administration of 0.09 mg/kg [14C]albitiazolium and was recalculated for a dose of 3.74 mg/kg. The flow of albitiazolium in the body, based on the PK profiles, is represented by red arrows (solid arrows, high flow; dashed arrows, low flow).

Administration of IRBC loaded with [14C]albitiazolium to healthy mice showed that albitiazolium plasma levels were up to 3 times higher than those observed after administration of an equal dose of albitiazolium in saline solution (Fig. 3A and Table 3). The drug release phenomenon was demonstrated by incubating the loaded IRBC in vitro (3 h in RPMI 1640–10% fetal calf serum). Under these conditions, the albitiazolium concentration decreased by 20 μM in the cellular fraction and concomitantly increased by 15 μM in the supernatant (Fig. S2). This clearly indicated that albitiazolium can be directly released from IRBC into the bloodstream and that IRBC behave as a drug reservoir.

In the spleen, the AUC increased to a much higher extent after administration of albitiazolium-loaded IRBC than after injection of the drug in saline solution (Fig. 3 and Table 3). This likely reflects the capture and/or destruction of the loaded IRBC in the spleen. The amount of albitiazolium in the spleen (calculated using the weight of the spleen and the albitiazolium spleen exposure) of 0.027 μmol · h was similar to the total amount of the drug in the intra- and extracellular space (0.029 μmol · h, calculated using the initial distribution volume and the albitiazolium plasma exposure). The spleen was thus a substantial source of albitiazolium and also constituted a reservoir that slowly released the drug into the plasma. Therefore, the observed albitiazolium concentrations in the plasma seem to be the result mainly of spleen activity and, to a lesser extent, of the direct release from IRBC (Fig. 7).

Our results presented here clearly demonstrate that released albitiazolium has antimalarial activity (Fig. 4). Whether the totality or a fraction of the drug is still active is currently unknown. Previous studies showed that a part of the accumulated bisthiazolium salts is bound to hemozoin (13, 17), forming a complex that could prevent the pharmacological activity of the bound compound. This study revealed that the albitiazolium accumulated in vivo by infected erythrocytes can be released into the plasma when the parasites die. This allows drug recycling, thereby extending its pharmacological activity.

Treatment of Plasmodium with bisthiazolium salts results in delayed morphological alterations and in the destruction of the parasites in vitro (14) and in vivo (Fig. 2F). We therefore wanted to define the timing of the irreversible damage done to the parasites through the measurement of their viability early after treatment. Every marker of cell death processes, such as necrosis, apoptosis, mitotic catastrophe, or arrest of metabolism, possesses its own limit (18). The test developed here quantifies the viability of parasites collected from mice treated in vivo by measuring their ability to proliferate in healthy mice, thereby changing from morphological to biological definitions of the pharmacological activity.

Our results showed that the pharmacological activity of albitiazolium is indeed very rapid. The number of viable parasites was reduced by 99.9% in less than 6 h when treatment started at the ring stage and less than 3 h when treatment started at mature stages (Fig. 5A to C). A second drug administration had a similar efficiency, killing 99.9% of the 0.1% parasites that had escaped the first drug pulse (Fig. 5D and E).

Knowing the number of viable parasites after the treatment allowed us to determine the parasite reduction ratio (PRR), which is the ratio of the total parasite burden of the mice at the time of treatment to the count one cycle later (24 h for P. vinckei). This represents the fractional reduction per asexual life cycle, or the killing rate (19). The PRR were found to be 1,138 and 3,380 after treatment at the ring and mature stages, respectively. After two doses at 12-h intervals, the PRR was 2.8 × 106. These high PRR are similar to those obtained for artemisinin derivatives (19), indicating that albitiazolium might be suitable for short-course treatments.

Very similar results were obtained in vitro with P. falciparum cultures. As controls, we tested atovaquone and dihydroartemisinin and obtained results similar to those published by Sanz et al. (16) (data not shown). Parasite viability was rapidly affected by albitiazolium treatment and was affected long before parasite morphology was affected. The PRR was 1.4 × 104 at 100× IC50. The viability of P. falciparum was less rapidly affected than that of P. vinckei. This discrepancy could be due to the different life cycle duration (48 h for P. falciparum and 24 h for P. vinckei) and/or to the difference between in vitro and in vivo experiments, i.e., the action of the spleen in the removal of infected erythrocytes.

The rapid onset of the pharmacological action is likely due to the fast and irreversible accumulation of albitiazolium within the intracellular parasite, which is then condemned to die, even though morphological effects occur only later. Thus, the parasite accumulates the drug and creates a Trojan horse to its own detriment. This also means that the real pharmacological effect is dissociated from the effects on parasite morphology and on the level of parasitemia.

We hypothesize that this Trojan horse effect explains why the dose leading to the total cure (0.37 mg/kg) is very close to the efficient dose required to decrease the level of parasitemia by 50% (ED50 = 0.22 mg/kg) after 4 days of treatment by the i.p. route at an initial parasitemia of 0.5 to 1% (S. Wein and H. J. Vial, unpublished data). At a higher initial parasitemia (5 to 10%), both the ED50 and the dose required for complete cure were 0.37 mg/kg. We explain this lack of a difference by the fact that the parasites still counted under the microscope were already condemned to death, thereby distorting the determination of the ED50 value.

The new in vivo viability test that we present here discriminates fast- and slow-acting antimalarials by determining the time needed to impair parasite viability. Indeed, this is a crucial parameter in the development of new antimalarials and should ideally be as fast as possible. In this test, PK parameters are taken into account and the effect on viability is the result of both the mode of action and the elimination half-life, unlike under in vitro conditions. Moreover, this test can be helpful to determine the minimal time of exposure to lethal drug concentrations for clinical development.

In conclusion, we determined the fate of albitiazolium in vivo and the kinetics of its pharmacological activity. Comparison with our clinical data showed that the P. vinckei-infected mouse model is reliable for obtaining an understanding of the fate of a drug in vivo before starting phase II clinical trials. Comprehensive PK/PD experiments and the new in vivo assay of viability could provide valuable support during the program of development of new antimalarials and could be used as a guide for the future design of clinical studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Albitiazolium {albitiazolium bromide, 3,3′-dodecane-1,12-diylbis[5-(2-hydroxyethyl)-4-methyl-1,3-thiazol-3-ium] dibromide} and [thiazole-2,2′-14C]albitiazolium were provided by Sanofi. Throughout this article, the doses of albitiazolium (in milligrams per kilogram) are expressed in the form of the dose of the bis-charged compound.

Animals and parasites.

Specific-pathogen-free female albino Swiss mice weighing 22 to 26 g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Saint Aubin-les-Elbeuf, France). They were kept at constant temperature (20 to 24°C) and 40 to 70% relative humidity with a standard 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. Animals were housed in stainless steel cages with suspended wire-mesh floors (a maximum of 9 mice per cage). The mice were fed a standard rodent controlled pelleted diet (Safe, Epinay Sur Orge, France) and allowed free access to tap water. All animals underwent a period of 1 week of observation and acclimatization before treatment. Mice were randomly distributed into three different groups. They were infected with P. vinckei petteri (279 BY strain) (20, 21) (I. Landau, Paris, France), maintained by weekly passage by i.p. administration.

This research conforms to national and European regulations (EU directive no. 86/609, modified by directive 2010/63 regarding the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes) and the laws of the member states of the partners. The animal studies were performed at the Centre d'Elevage et de Conditionnement Experimental des Modèles Animaux, Montpellier, France, under permission no. B-34-172-23 (University of Montpellier) after approval by the Animal Experimenting Commission.

Counting of parasites.

Parasitemia was routinely monitored on thin blood smears fixed in methanol and stained with Diff-Quick (pH 7.2; Dade Behring, France) or by flow cytometry on blood samples using Yoyo-1 iodide (491 nm excitation/509 nm emission; Invitrogen, France) (22). For microscopy determination, at least 1,000 cells were counted.

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic study of albitiazolium.

Two groups of 94 mice each were inoculated intravenously with 107 (first group) or 108 (second group) P. vinckei-infected erythrocytes (resuspended in 0.2 ml of sterile isotonic saline solution). A third group of 90 mice remained uninfected. Thirty additional untreated animals were used to provide predose blood and tissue samples to prepare calibration curves and quality control samples.

Mice were fasted overnight (12 h) before drug administration and then weighed. Drug treatment was initiated when the parasitemia was between 0.5 and 1% (first group) and between 8 and 12% (second group). In each infected group, four mice (control) did not receive treatment to evaluate the development of parasitemia. Albitiazolium was prepared in 0.9% sterile isotonic saline on the day of administration and was administered i.p. at a dose of 3.7 mg/kg. The administered volume was 3.12 ml/kg (i.e., ∼100 μl per mouse).

The level of parasitemia was determined by counting the number of parasites, which was performed on samples at each blood sampling time.

Blood and tissues (heart, liver, and brain) were obtained at the following times: 5, 15, and 30 min and 1, 2, 4, 6, 11, 24, and 35 h after treatment. At each time point, 9 mice were sacrificed and three pools of 3 mice each prepared. Blood samples were collected in heparinized polypropylene tubes. Thereafter, the tubes were gently agitated to prevent coagulation and then centrifuged (2,000 × g) at 4°C for 15 min. The plasma was separated and immediately stored at −80°C. The cell pellet was washed twice with an equal volume of 0.9% sodium chloride to limit plasma contamination before storage at −80°C. Tissues were washed twice for 30 s each time in 0.9% sodium chloride to limit blood contamination, dried on gauze, placed in a polypropylene tube, and then frozen at −80°C.

Quantification of albitiazolium in erythrocytes and plasma.

Albitiazolium was quantified in red blood cells (RBC), infected red blood cells (IRBC), and plasma using a liquid chromatography (LC)-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) method (23). Briefly, the method involved solid-phase extraction using OasisHLB columns after protein precipitation. LC separation was performed on a Zorbax eclipse XD8 C8 column (5 μm) with a mobile phase of acetonitrile containing 130 μl/liter trimethylamine and 2 mM ammonium formate buffer (pH 3). MS data were acquired in the single-ion-monitoring mode at m/z 227.3 for albitiazolium and m/z 326 for the internal standard. The precision was below 14%, and the accuracy was 91.4 to 104%. The lower limits of quantitation were 3.65 nM in plasma and 7.26 nM in RBC.

Quantification of albitiazolium in tissues.

Albitiazolium concentrations in tissues were quantified using the rapid-resolution LC-ESI-MS method (24). Before sample pretreatment using Oasis WCX cartridges, tissues were powdered under liquid nitrogen. LC separation was performed on a Zorbax Eclipse XDB C8 column (1.8 μm) using a mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile-trimethylamine-formate buffer at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The assay precision was <13%, and the accuracy was 90 to 107%. The lower limits of quantitation were 7.26 nmol/kg in brain and 72.6 nmol/kg in liver and heart.

Animal samples were processed with a standard curve, and quality control samples were included in each analytical sequence to verify the stability of study samples during storage and the accuracy and the precision of the analysis.

In vivo cellular accumulation ratio.

At each time of sampling, in both infected groups, the albitiazolium concentration in 100% infected RBC (CIRBC) was calculated as follows: CIRBC = [CRBC + IRBC − (100 − P) × CRBC]/P, where CRBC + IRBC is the albitiazolium concentration measured in the erythrocyte fraction (infected plus uninfected erythrocytes); CRBC is the concentration in uninfected RBC, assuming that it corresponds to the concentration found in treated healthy mice; and P is the level of parasitemia.

The cellular accumulation ratio (CAR) was defined as the ratio of the concentration of albitiazolium in 100% infected cells to that in the same volume of plasma. The CAR was also calculated for the uninfected group.

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

PK analysis was carried out on the basis of the average concentration values at each time point using Pk-fit software (25, 26).

From the plasma, RBC, or IRBC data, PK parameters were determined using a compartmental approach. The following parameters were calculated: the total area under the concentration-time curves from time zero to infinity (AUC0–inf), elimination half-life (t1/2 elim), total clearance (CL/F), and the steady-state volume of distribution (V/F). CL and V were uncorrected for bioavailability (F). The highest observed concentration was designated Cmax. The time of Cmax relative to the time of dosing was designated Tmax. Cmax and Tmax were observed values.

From tissue data, AUC and t1/2 elim were calculated using a noncompartmental approach.

Comparative pharmacokinetics of [14C]albitiazolium administered in saline solution or in loaded IRBC.

Experiments with radioactive compound were performed in a room at UMR5235 dedicated to radioactivity manipulation (under permission no. T340403, delivered by the Autorité de Sûreté Nucléaire) after approval by the Animal Experimenting Commission.

Naive mice received [14C]albitiazolium intravenously (i.v.) in the form of either 100 μl of loaded erythrocytes (RBC plus IRBC) (50% hematocrit) or 100 μl of saline solution, both of which contained either 0.15 or 0.09 mg/kg. The mice were weighed just before injection. The distribution of albitiazolium between RBC and IRBC was evaluated. Albitiazolium is almost entirely found in IRBC, which contained more than 90% of the drug in both suspensions (data not shown). This means that almost all the drug released in the plasma is provided by IRBC. For this reason and for clarity, we decided to use the term “loaded IRBC” throughout the text.

Fifteen mice were inoculated intravenously with 108 P. vinckei-infected RBC (resuspended in 0.2 ml of 0.9% sterile isotonic saline). When the level of parasitemia in the mice was between 20 and 50%, blood was collected in heparinized polypropylene tubes. RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) was added to obtain a suspension at 5% hematocrit. This suspension was preincubated for 5 min at 37°C before addition of 500 μM (suspension at 29% parasitemia) or 100 μM (suspension at 50% parasitemia) [14C]albitiazolium with a specific activity of 23.8 mCi/mmol to each tube. The suspensions were incubated for 90 min at 37°C and then centrifuged (805 × g) at 4°C for 10 min, and the cells were washed twice with 0.9% NaCl. Cells were resuspended in 0.9% NaCl at 50% hematocrit. The [14C]albitiazolium contained in IRBC incubated at 37°C was quantified by liquid scintillation counting as described below for total blood. After quantification, we determined that injection of 100 μl of these suspensions into mice corresponds to a dose of 0.15 mg/kg or 0.09 mg/kg albitiazolium for IRBC incubated in the presence of 500 μM or 100 μM albitiazolium, respectively.

Blood, spleen, and liver were collected at 1, 5, 15, and 30 min and 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 11, 23, 33, and 46.33 h after the i.v. injection. At each time point, the levels of parasitemia and hematocrit were determined for each mouse (3 mice per time point). Blood samples were collected, and aliquots of blood were taken to determine the dose of radioactivity in total blood, IRBC, and plasma. After collection, tissues were washed twice in 0.9% NaCl, dried on gauze, and frozen at −80°C.

Quantification of [14C]albitiazolium.

Albitiazolium in total blood was measured directly in a scintillation vial. One hundred microliters of total blood was lysed by the addition of 200 μl distilled water and then solubilized and decolorized by the addition of 500 μl of a decolorization cocktail containing 5 parts of tissue solubilizer (Solvable; PerkinElmer), 2 parts of 30% H2O2, and 2 parts of glacial acetic acid.

For IRBC, 100 μl of total blood was overlaid onto 400 μl of dibutyl phthalate and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min at 4°C, with the cells sedimenting below the oil. The supernatant was removed, and the walls of the microtube were washed once with 200 μl of 0.9% NaCl. After centrifugation (1 min at 10,000 × g), the washing buffer and the dibutyl phthalate were discarded. The cell pellets were lysed and treated as described above for total blood samples.

The albitiazolium concentration in plasma was also determined. After centrifugation of a blood aliquot at 4°C for 10 min (1,800 × g), the plasma was transferred to scintillation vials.

The counts in samples of total blood, IRBC, and plasma were then determined by liquid scintillation counting after addition of 2.5 ml of scintillation cocktail (Ultima Gold; PerkinElmer).

Spleens were powdered under liquid nitrogen in a scintillation vial. Then, cells were completely lysed with 300 μl of H2O, frozen-thawed, and solubilized and decolorized by the addition of 500 μl of the decolorization cocktail. Radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting after addition of 3 ml of scintillation cocktail.

Livers were crushed directly in 20-ml scintillation vials. Then, residues were completely lysed with 1 ml of H2O, frozen-thawed twice, and then solubilized and decolorized by the addition of 2 ml of the decolorization cocktail. Radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting after addition of 10 ml of scintillation liquid.

The quenching factor for the different sample types was determined, and the values were corrected accordingly. PK analysis was carried out as described above.

Pharmacological activity of albitiazolium released in mouse plasma.

Plasma samples containing released albitiazolium were collected from mice that had received 0.14, 0.15, or 0.18 mg/kg albitiazolium injected as loaded IRBC. The IRBC had been loaded with 100 μM nonradioactive albitiazolium as described above, but the albitiazolium was quantified by LC-MS. The three batches of loaded IRBC (batches 1, 2, and 3) contained 7.1, 6.9, and 8.6 nmol per 200 μl of suspension, respectively. Naive mice received intravenously 200 μl of these suspensions (five mice per batch), corresponding to doses of 0.11, 0.10, and 0.13 mg/kg albitiazolium for batches 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Blood was collected 15 min after administration, and the plasma fraction, containing the released albitiazolium, was obtained by centrifugation of the blood sample at 4°C for 5 min (1,800 × g). The three batches of plasma containing the released albitiazolium were dosed by LC-MS, and batches 1, 2, and 3 contained 404, 315, and 395 nM albitiazolium, respectively. Then, an independent batch of P. vinckei-infected RBC collected from one mouse with a parasitemia of 26% was incubated with the three batches of plasma containing released albitiazolium or with plasma from naive mice (control) at 10% hematocrit for 1 h at 37°C. Thereafter, 200 μl of these suspensions (IRBC plus plasma) was injected into naive mice (3 mice per batch). The development of parasitemia was followed by Giemsa staining of smears for the recipient mice and was a function of the number of infectious (viable) injected parasites after incubation in plasma.

Effect of albitiazolium administration on parasitemia and parasite viability.

The number of parasites visible in a blood smear after albitiazolium treatment does not necessarily correspond to the number of viable parasites. To distinguish between visible and viable parasites, we determined the number of viable parasites by inoculating treated parasites from donor mice into recipient (uninfected) mice and monitoring their parasitemia. Initially, we investigated the effect of a single dose of albitiazolium at the ring or mature stages. Donor mice were infected by 2 × 107 P. vinckei-infected erythrocytes by the i.v. route in the caudal vein on day 0 (at about 11:00 a.m.). On day 1 (at 5:00 p.m.), the parasites were predominantly at the ring stage at a parasitemia of 2.6%. On day 2 (at 5:00 a.m.), the parasites were at mature stages at a parasitemia of 5.8%. At each of these stages, the donor mice were treated (or not treated, for the controls) with a single dose of 7.4 mg/kg albitiazolium by the i.p. route.

Subsequently, we compared the effect of repeated doses on mature parasites. Donor mice were infected as described above on day 0. On day 1, when the parasites were at 2% mature stages (0 h after the end of log-phase growth [T0]), one group of mice was not treated, the second group received a single dose i.p. of 7.4 mg/kg albitiazolium at T0, and the third group received two injections at a 12-h interval. The dose at T0 was 7.4 mg/kg, and the dose 12 h after the end of log-phase growth (T12) was 3.7 mg/kg, to avoid a possible toxic effect of albitiazolium.

For both experiments, blood was collected from control and treated mice at different times after the treatment (two mice per point), the drug was washed off, and the cells were immediately injected into two recipient mice (100 μl reconstituted blood per mouse). The level of parasitemia in these recipient mice is a function of the number of injected infectious (viable) parasites. This number was calculated on the basis of the parasite multiplication ratio (PMR), which we had observed to be linear up to 30% parasitemia. The PMR over 24 h is the number of parasites on day x divided by the number of parasites on day x − 1. As expected, the PMR was similar between recipient and donor mice.

The level of parasitemia in the recipient mice just after inoculation of treated parasites was back-calculated by the following formula: parasitemia of mice treated on day 1 = parasitemia on day x/PMRx − 1, and parasitemia of mice treated on day 2 = parasitemia on day x/PMRx − 2. The total number of viable parasites in donor mice was then calculated (total blood volume of mouse, ∼7 ml/100 g of body weight; 9 × 109 RBC/ml of total blood volume).

In vitro P. falciparum culture.

The P. falciparum 3D7 strain (MRA-102 from the Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center) was cultured in human RBC (Etablissement Français du Sang, Montpellier, France) at 5% hematocrit in complete medium composed of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) and 10% type AB-positive human serum (27). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a culture gas chamber under a gaseous mixture of 5% CO2, 5% O2, and 90% N2. For in vitro parasite viability assays, asynchronous cultures at 2% hematocrit and 0.5% parasitemia were maintained under shaking to reduce the number of RBCs invaded by more than one parasite.

In vitro parasite viability assay.

The effects of the drug on parasite viability were determined as described by Sanz et al. (16). IRBC were treated (or not treated) with albitiazolium at concentrations corresponding to 3×, 10×, or 100× its IC50 (the concentration required to inhibit parasite viability by 50%) (albitiazolium IC50 = 3 nM). Culture medium with or without drug was changed every 24 h during the entire treatment period. At times of 0, 2, 4, 6, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, thin blood smears were realized to calculate the number of visible parasites, and samples of untreated or treated parasites were taken to determine the number of viable parasites. Samples were washed twice to eliminate the drug and then added to 96-well plates, and 3-fold serial dilutions were performed. Parasites were cultured for 21 days to reach a detectable parasitemia in wells started from only one viable parasite. The culture medium was changed twice a week. The presence of parasites was detected by determination of the level of [3H]hypoxanthine incorporation for 24 h. The most diluted well with significant [3H]hypoxanthine incorporation corresponds to the well initially containing only one parasite after serial dilution. The numbers of viable parasites were back-calculated by using the formula Xn − 1, where n is the number of wells able to render growth and X is the dilution factor (16).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Cathy Cantalloube for her feedback on human pharmacokinetics and Arran Hodgkinson for critical reading of the manuscript. The P. falciparum 3D7 strain was obtained through the Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center (MR4; https://www.beiresources.org/MR4Home.aspx).

The research leading to these results has benefited from funding from the European Community's Framework Programme, Antimal Integrated Project (LSHP-CT-2005-018834); the EviMalar Network of Excellence (FP7/2007-2013, no. 242095); Sanofi; and the Innomad/Eurobiomed Program of the Pole of Competitiveness.

Laurent Fraisse is a full-time employee of Sanofi.

S.W. planned and designed the study, acquired and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; M.M., C.T.V.B, Y.B., N.T., and D.M. acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data; R.C. and K.W. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript, F.B.-G. performed the PK experiments and modeled the PK; L.F. designed the study; and H.J.V. planned and designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00352-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2016. World malaria report 2016. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells TN, Hooft van Huijsduijnen R, Van Voorhis WC. 2015. Malaria medicines: a glass half full? Nat Rev Drug Discov 14:424–442. doi: 10.1038/nrd4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vial HJ, Ancelin ML. 1992. Malarial lipids. An overview. Subcell Biochem 18:259–306. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1651-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vial HJ, Ben Mamoun C. 2005. Plasmodium lipids: metabolism and function p 327–352. In Sherman IW. (ed), Molecular approaches to malaria. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vial HJ, Eldin P, Tielens AG, van Hellemond JJ. 2003. Phospholipids in parasitic protozoa. Mol Biochem Parasitol 126:143–154. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(02)00281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ancelin ML, Calas M, Bompart J, Cordina G, Martin D, Ben Bari M, Jei T, Druilhe P, Vial HJ. 1998. Antimalarial activity of 77 phospholipid polar head analogs: close correlation between inhibition of phospholipid metabolism and in vitro Plasmodium falciparum growth. Blood 91:1426–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ancelin ML, Calas M, Vidal-Sailhan V, Herbute S, Ringwald P, Vial HJ. 2003. Potent inhibitors of Plasmodium phospholipid metabolism with a broad spectrum of in vitro antimalarial activities. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:2590–2597. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2590-2597.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calas M, Ancelin ML, Cordina G, Portefaix P, Piquet G, Vidal-Sailhan V, Vial H. 2000. Antimalarial activity of compounds interfering with Plasmodium falciparum phospholipid metabolism: comparison between mono- and bisquaternary ammonium salts. J Med Chem 43:505–516. doi: 10.1021/jm9911027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamze A, Rubi E, Arnal P, Boisbrun M, Carcel C, Salom-Roig X, Maynadier M, Wein S, Vial H, Calas M. 2005. Mono- and bis-thiazolium salts have potent antimalarial activity. J Med Chem 48:3639–3643. doi: 10.1021/jm0492608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vial HJ, Wein S, Farenc C, Kocken C, Nicolas O, Ancelin ML, Bressolle F, Thomas A, Calas M. 2004. Prodrugs of bisthiazolium salts are orally potent antimalarials. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:15458–15463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404037101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Roch KG, Johnson JR, Ahiboh H, Chung DW, Prudhomme J, Plouffe D, Henson K, Zhou Y, Witola W, Yates JR, Mamoun CB, Winzeler EA, Vial H. 2008. A systematic approach to understand the mechanism of action of the bisthiazolium compound T4 on the human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Genomics 9:513. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wein S, Maynadier M, Bordat Y, Perez J, Maheshwari S, Bette-Bobillo P, Tran Van Ba C, Penarete-Vargas D, Fraisse L, Cerdan R, Vial H. 2012. Transport and pharmacodynamics of albitiazolium, an antimalarial drug candidate. Br J Pharmacol 166:2263–2276. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biagini GA, Richier E, Bray PG, Calas M, Vial H, Ward SA. 2003. Heme binding contributes to antimalarial activity of bis-quaternary ammoniums. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:2584–2589. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2584-2589.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wein S, Tran Van Ba C, Maynadier M, Bordat Y, Perez J, Peyrottes S, Fraisse L, Vial HJ. 2014. New insight into the mechanism of accumulation and intraerythrocytic compartmentation of albitiazolium, a new type of antimalarial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:5519–5527. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00040-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wein S, Maynadier M, Tran Van Ba C, Cerdan R, Peyrottes S, Fraisse L, Vial H. 2010. Reliability of antimalarial sensitivity tests depends on drug mechanisms of action. J Clin Microbiol 48:1651–1660. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02250-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanz LM, Crespo B, De-Cozar C, Ding XC, Llergo JL, Burrows JN, Garcia-Bustos JF, Gamo FJ. 2012. P. falciparum in vitro killing rates allow to discriminate between different antimalarial mode-of-action. PLoS One 7:e30949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richier E, Biagini GA, Wein S, Boudou F, Bray PG, Ward SA, Precigout E, Calas M, Dubremetz JF, Vial HJ. 2006. Potent antihematozoan activity of novel bisthiazolium drug T16: evidence for inhibition of phosphatidylcholine metabolism in erythrocytes infected with Babesia and Plasmodium spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:3381–3388. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00443-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Abrams JM, Alnemri ES, Baehrecke EH, Blagosklonny MV, Dawson TM, Dawson VL, El-Deiry WS, Fulda S, Gottlieb E, Green DR, Hengartner MO, Kepp O, Knight RA, Kumar S, Lipton SA, Lu X, Madeo F, Malorni W, Mehlen P, Nunez G, Peter ME, Piacentini M, Rubinsztein DC, Shi Y, Simon HU, Vandenabeele P, White E, Yuan J, Zhivotovsky B, Melino G, Kroemer G. 2012. Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death Differ 19:107–120. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White NJ. 1997. Assessment of the pharmacodynamic properties of antimalarial drugs in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:1413–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter R, Walliker D. 1975. New observations on the malaria parasites of rodents of the Central African Republic—Plasmodium vinckei petteri subsp. nov. and Plasmodium chabaudi Landau, 1965. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 69:187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landau I, Gautret P. 1998. Animal models: rodents, p 401–417. In Sherman IW. (ed), Malaria: parasite biology, pathogenesis, and protection. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barkan D, Ginsburg H, Golenser J. 2000. Optimisation of flow cytometric measurement of parasitaemia in Plasmodium-infected mice. Int J Parasitol 30:649–653. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taudon N, Margout D, Wein S, Calas M, Vial HJ, Bressolle FM. 2008. Quantitative analysis of a bis-thiazolium antimalarial compound, SAR97276, in mouse plasma and red blood cell samples, using liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal 46:148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margout D, Wein S, Gandon H, Gattacceca F, Vial HJ, Bressolle FM. 2009. Quantitation of SAR97276 in mouse tissues by rapid resolution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Sep Sci 32:1808–1815. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farenc C, Fabreguette JR, Bressolle F. 2000. Pk-fit: a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic and statistical data analysis software. Comput Biomed Res 33:315–329. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.2000.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Research Development in Population Pharmacokinetics. 2000. Pk-fit software, version 2.1. Research Development in Population Pharmacokinetics, Montpellier, France. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trager W, Jensen JB. 1976. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science 193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.