ABSTRACT

Flaviviruses are positive-strand RNA viruses distributed all over the world that infect millions of people every year and for which no specific antiviral agents have been approved. These viruses include the mosquito-borne West Nile virus (WNV), which is responsible for outbreaks of meningitis and encephalitis. Considering that nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) has been previously shown to inhibit the multiplication of the related dengue virus and hepatitis C virus, we have evaluated the effect of NDGA, and its methylated derivative tetra-O-methyl nordihydroguaiaretic acid (M4N), on the infection of WNV. Both compounds inhibited the infection of WNV, likely by impairing viral replication. Since flavivirus multiplication is highly dependent on host cell lipid metabolism, the antiviral effect of NDGA has been previously related to its ability to disturb the lipid metabolism, probably by interfering with the sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBP) pathway. Remarkably, we observed that other structurally unrelated inhibitors of the SREBP pathway, such as PF-429242 and fatostatin, also reduced WNV multiplication, supporting that the SREBP pathway may constitute a druggable target suitable for antiviral intervention against flavivirus infection. Moreover, treatment with NDGA, M4N, PF-429242, and fatostatin also inhibited the multiplication of the mosquito-borne flavivirus Zika virus (ZIKV), which has been recently associated with birth defects (microcephaly) and neurological disorders. Our results point to SREBP inhibitors, such as NDGA and M4N, as potential candidates for further antiviral development against medically relevant flaviviruses.

KEYWORDS: West Nile virus, antiviral agents, flavivirus, lipid, Zika virus

INTRODUCTION

West Nile virus (WNV) is a member of the Flavivirus genus within the Flaviviridae family. Its genome is composed by a single-stranded RNA molecule of positive polarity about 11,000 nucleotides in length (1). This mosquito-borne flavivirus is distributed worldwide and causes outbreaks of febrile illness and meningoencephalitis (2). Although WNV poses a health threat, there is still neither a vaccine nor an antiviral therapy licensed for human use. Apart from WNV, the Flavivirus genus includes other well-known pathogens, such as yellow fever virus, dengue virus (DENV), Japanese encephalitis virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, and Zika virus (ZIKV). ZIKV has recently gained attention because it is responsible for a global outbreak infecting millions of people and has been associated with birth defects (microcephaly) and neurological disorders like Guillain-Barré syndrome (3, 4). Similar to WNV, there are neither specific drugs nor vaccines licensed against ZIKV.

Recent advances have revealed that positive-stranded RNA viruses, including the flaviviruses, rearrange host cell lipid metabolism and coopt for cellular lipids to complete their life cycle (5–7). Considering this dependence on lipid metabolism during flavivirus infection, pharmacological modification of the lipid metabolic pathways appears to be a proper strategy to impair flaviviral replication (7, 8). Along these lines, the hypolipidemic drug nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) has been reported to inhibit replication of the flavivirus DENV (9). In addition, NDGA also inhibited the replication of hepatitis C virus (HCV), a member of the Hepacivirus genus within the Flaviviridae family (10), thus becoming an interesting candidate for broad antiviral development against flaviviruses and related viruses. NDGA is a phenolic compound and the main metabolite of the desert shrub Larrea tridentata. Nowadays, NDGA is being evaluated to treat a wide variety of illnesses, including diabetes, pain, inflammation, infertility, rheumatism, arthritis, and gallbladder and kidney stones (11, 12). Remarkably, a synthetic methylated derivative of NDGA, termed tetra-O-methyl nordihydroguaiaretic acid (M4N, Terameprocol, or EM-1421), which retains a high similarity in the molecular structure with its precursor, is currently in phase I/II clinical trials in patients with advanced cancer (13–15). However, to our knowledge, the potential antiviral effect of M4N has not been assessed against any flavivirus.

In this work, we have evaluated the antiviral effect of NDGA and its M4N derivative on the infection of medically relevant flaviviruses. Our results showed that both compounds inhibited WNV and ZIKV infection.

RESULTS

NDGA and M4N inhibit WNV infection.

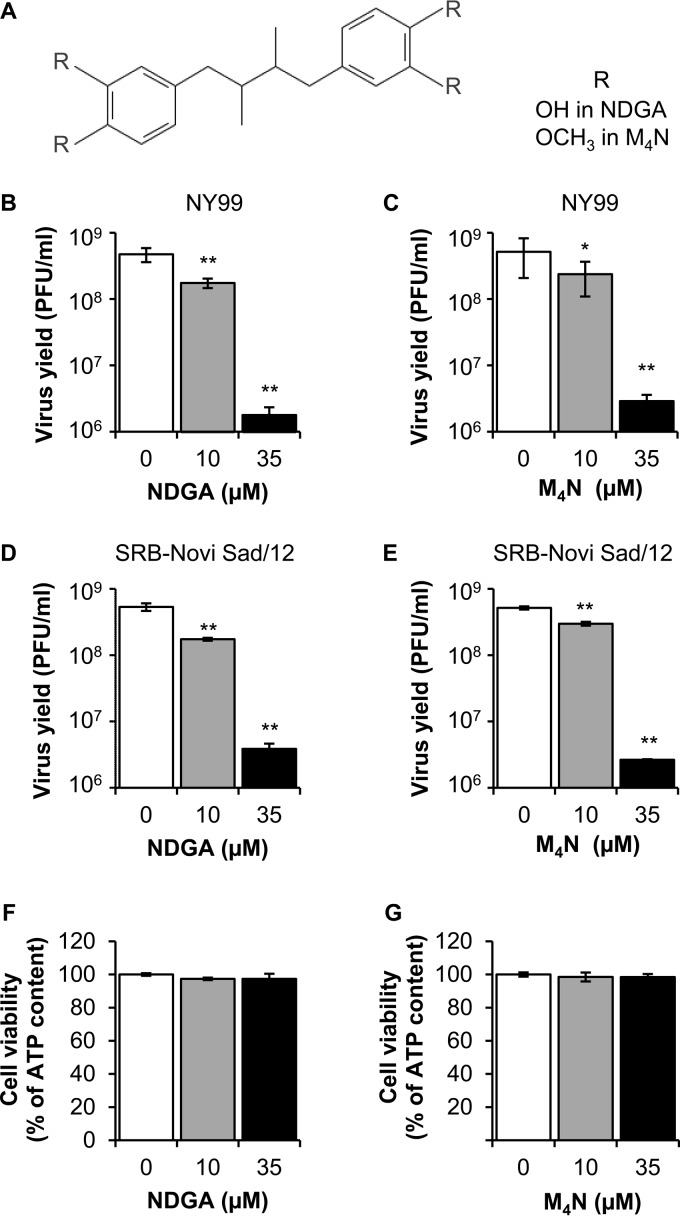

The antiviral activity against WNV of NDGA and its synthetic methylated derivative M4N was explored (Fig. 1A). Vero cells were infected and treated with different concentrations of the drugs (10 or 35 μM) at 1 hour postinfection (h p.i.), and the virus yield was determined by plaque assay at 24 h p.i. Both NDGA and M4N reduced significantly the virus yield in a dose-dependent manner when cells were infected with a highly neurovirulent WNV strain from genetic lineage 1 (WNV NY99) representative of the virus that is currently circulating in the American continent (Fig. 1B and C). In a similar manner, both NDGA and M4N also reduced significantly the virus yield of a WNV strain from genetic lineage 2 (WNV SRB-Novi Sad/12) representative of the highly neurovirulent virus that has recently colonized the European continent (Fig. 1D and E). The lack of toxicity of the drug concentrations utilized was analyzed in parallel by determination of the cellular ATP content (Fig. 1F and G). Results showed no statistically significant reduction of the cellular ATP content at the drug concentrations used, confirming that the reduction of viral yield was not associated with major cytotoxic effects of the drugs. Considering that there were no marked differences on the antiviral effect of NDGA and M4N between the two WNV isolates analyzed (Fig. 1B to E), the WNV NY99 strain was selected for subsequent experiments.

FIG 1.

NDGA and its synthetic derivative M4N inhibit WNV infection. (A) Chemical structure of NDGA and M4N. R corresponds to OH in NDGA or OCH3 in M4N. (B and C) Reduction of WNV infection in Vero cells treated with NDGA (B) or M4N (C). Cells were infected with WNV lineage 1 strain NY99 (MOI of 1 PFU/cell), and virus yield in culture supernatant was determined by plaque assay at 24 h p.i. (D and E) Inhibition of WNV lineage 2 infection in Vero cells treated with NDGA (D) or M4N (E). Cells were infected with WNV SRB-Novi Sad/12 (MOI of 1 PFU/cell), and virus yield in culture supernatant was determined by plaque assay at 24 h p.i. (F and G) Evaluation of the cytotoxicity of NDGA (F) and M4N (G) on Vero cells by determination of ATP content 24 h posttreatment. Data are presented as means ± SDs (n = 3 to 6). Statistically significant differences are indicated. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005.

Inhibition of WNV infection by M4N is not related to a virucidal effect.

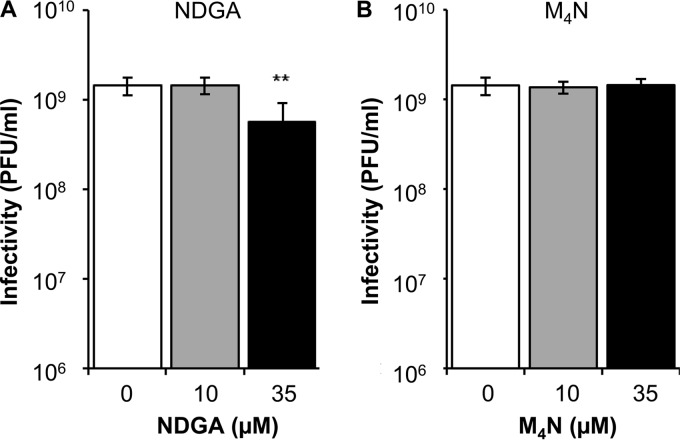

To evaluate a possible virucidal effect of NDGA and M4N, WNV (∼1.5 × 109 PFU) was preincubated with the compounds for 1 h at 37°C in culture medium and then titrated to determine the remaining infectivity. A significant reduction (Fig. 2A) was observed only when NDGA was tested at the highest concentration (35 μM); however, this was lower than that observed in the virus yield assays (Fig. 1A), thus suggesting that the inactivation of the virions by NDGA was not primarily related to a virucidal effect. No significant reduction of WNV infectivity was noticed in this assay when M4N was tested (Fig. 2B), indicating that this compound does not exhibit a virucidal effect against WNV.

FIG 2.

Evaluation of the direct effect of NDGA and M4N on the infectivity of WNV. WNV NY99 (∼1.5 × 109 PFU) was treated with NDGA (A) or M4N (B) for 1 h at 37°C in culture medium. Then, the infectivity in each sample was determined by plaque assay. Data are presented as means ± SDs (n = 4). Statistically significant differences are indicated. **, P < 0.005.

NDGA and M4N inhibit genome replication of WNV.

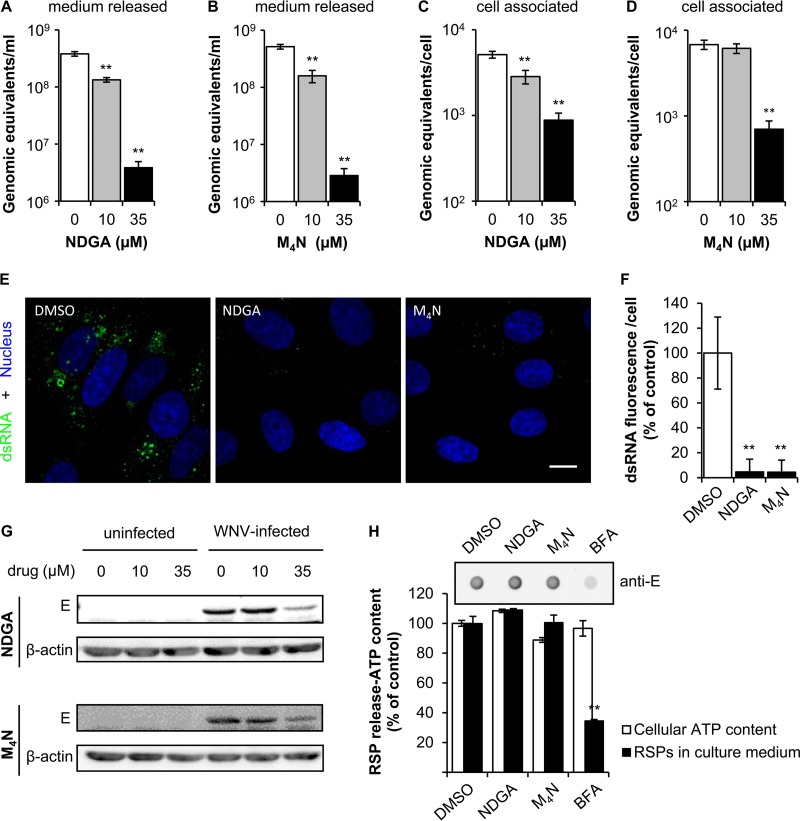

To identify the step that was mainly affected by NDGA and M4N, WNV infection was analyzed by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR). Both drugs significantly inhibited the release of WNV genome-containing particles to the culture medium (Fig. 3A and B). Moreover, NDGA and M4N significantly reduced the amount of cell-associated viral RNA, especially at 35 μM (Fig. 3C and D). Overall, these observations support that the reduction in the release of genome-containing particles was produced by a decrease in viral replication. The amount of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) intermediates, which provide a good indicator of flavivirus replication (16, 17), was also analyzed by immunofluorescence (Fig. 3E). Concordant with previous results, a major decrease in the amount of dsRNA was observed in cells treated with NDGA or M4N in comparison to that in untreated cells. The quantification of this signal (Fig. 3F) confirmed this observation, supporting that both NDGA and M4N inhibited WNV genome replication. Western blot analysis also revealed a reduction in the level of the viral E protein within infected cells treated with 35 μM NDGA (34% of control) or M4N (43% of control) (Fig. 3G).

FIG 3.

NDGA and M4N inhibit WNV replication. (A and B) Reduction of genome-containing particles in culture supernatant of Vero cells treated with NDGA (A) or M4N (B). Cells were infected with WNV NY99 (MOI of 1 PFU/cell), and the amount of genome-containing particles in culture supernatant was determined by quantitative RT-PCR at 24 h p.i. (C and D) Amount of cell-associated viral RNA in cell cultures infected with WNV and treated with NDGA (C) or M4N (D) as described in A and B. The amount of cell-associated RNA in each sample was normalized by quantification of rRNA 18S. (E) Visualization of intracellular dsRNA accumulation in cells infected with WNV NY99 (MOI of 10 PFU/cell) and treated with 35 μM NDGA or 35 μM M4N. Infected cells treated with drug vehicle (DMSO) were included as a control. Cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence using J2 monoclonal antibody to dsRNA and a secondary antibody coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 (green). Nuclei were stained with To-Pro-3 (blue). Bar, 10 μm. (F) Quantification of the fluorescence intensity of dsRNA in cells infected with WNV and treated with 35 μM NDGA or M4N as shown in E (n = 89, 36, and 39 cells analyzed for DMSO, NDGA, and M4N, respectively). (G) Western blot analysis of E glycoprotein expression in cells treated with NDGA or M4N. Vero cells were infected, or not, with WNV NY99 (MOI of 1 PFU/cell) and treated with different concentrations of NDGA or M4N. Membrane was retested against a β-actin antibody as a control for protein loading. (H) RSP release into the culture medium by HeLa3-WNV cells treated (4 h) with 35 μM NDGA, 35 μM M4N, or 5 μg/ml BFA was analyzed by enzyme-linked immunodot assay using a monoclonal antibody against E glycoprotein. The graph displays the quantification of the amount of RSPs released. For each drug, the cellular ATP content is also depicted as an indicator of the cell viability upon drug treatment. Data are presented as means ± SDs (n = 3 to 6). Statistically significant differences are indicated. **, P < 0.005.

The effect of NDGA and M4N on viral morphogenesis and particle egression was evaluated using a cell line that expresses WNV structural glycoproteins and constitutively secretes virus-like particles (termed recombinant subviral particles [RSPs]) without the need for viral replication (18, 19). For this experiment, cells were incubated for 4 h with the compounds, a time that has been previously shown to be sufficient for the identification of compounds that impair WNV biogenesis (19), and the amount of RSPs in the supernatant was analyzed. Immunoblot analysis of the supernatant using anti-E antibody revealed that no inhibition of RSP egress was observed when cells were treated with either NDGA or M4N (Fig. 3H). However, the inhibitor of secretion brefeldin A (BFA), included as a control, significantly inhibited the release of RSPs into the culture medium. Taken together, these results support that both NDGA and its derivative M4N impair WNV infection by reducing genome replication rather than virion morphogenesis or particle egress.

Resveratrol, PF-429242, and fatostatin reduce WNV infection.

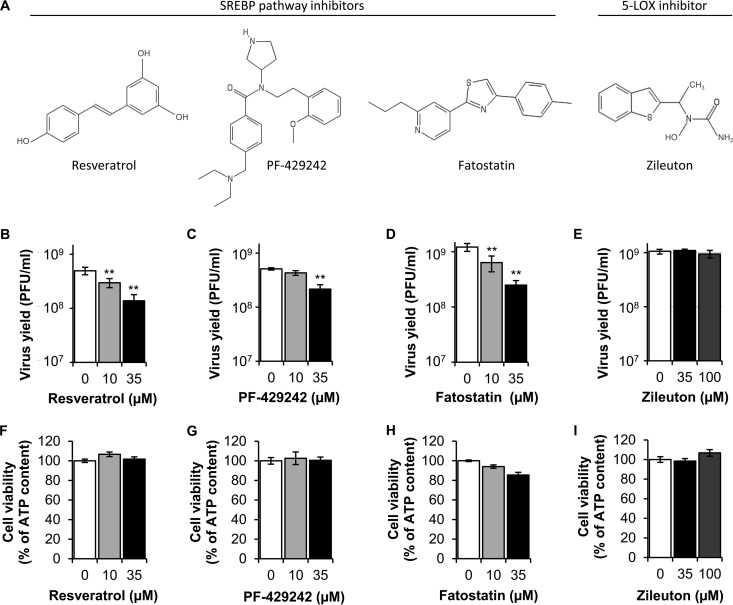

The antiviral effect of NDGA against DENV and HCV has been associated with the inhibition of lipogenesis (9, 10). Specifically, in the case of HCV, the antiviral effect of NDGA was related to its ability to impair the sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) pathway (10). The SREBPs are the main transcription factors that regulate lipid biosynthesis and lipid homeostasis in mammals (20, 21). To evaluate the involvement of the SREBP pathway on WNV infection, we selected resveratrol, PF-429242, and fatostatin (Fig. 4A), which are structurally unrelated compounds that inhibit different components or regulators of the SREBP pathway (22–25). Treatment with resveratrol resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of WNV infectious particle production (Fig. 4B). Likewise PF-429242 (Fig. 4C) and fatostatin (Fig. 4D) showed statistically significant suppression of infectious viral titers in a dose-dependent manner. In addition to its effect on the SREBP pathway, NDGA can also inhibit 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) activity in vitro (26, 27). Therefore, to discard that the antiviral effect of NDGA and M4N was due to 5-LOX inhibition, the inhibitor of 5-LOX zileuton was used (28). No inhibition of virus yield was observed when cells were treated with zileuton (Fig. 4E). These results suggested that whereas the infection of WNV was sensitive to the inhibition of the SREBP pathway, it was independent of 5-LOX activity. The lack of toxicity of all of the drug concentrations utilized was analyzed in parallel by determination of ATP content (Fig. 4F to I). All of the drug concentrations tested displayed cell viabilities higher than 80% of that of control cells, further supporting that the reductions of viral yields exerted by resveratrol, PF-429242, and fatostatin were not associated with cytotoxic effects of the drugs.

FIG 4.

Different inhibitors of the SREBP pathway reduce WNV infection. (A) Chemical structure of the SREBP pathway inhibitors tested: resveratrol, PF-429242, and fatostatin. The structure of zileuton, a 5-LOX inhibitor, is also depicted. (B to E) Quantification of WNV infectious particle production in Vero cells infected with WNV NY99 (MOI of 1 PFU/cell) and treated with resveratrol (B), PF-429242 (C), fatostatin (D), or zileuton (E). Virus yield in culture supernatant was determined by plaque assay at 24 h p.i. (F to I) Evaluation of the cytotoxicity of resveratrol (F), PF-429242 (G), fatostatin (H), and zileuton (I) on Vero cells by determination of ATP content 24 h posttreatment. Data are presented as means ± SDs (n = 4). Statistically significant differences are indicated. **, P < 0.005.

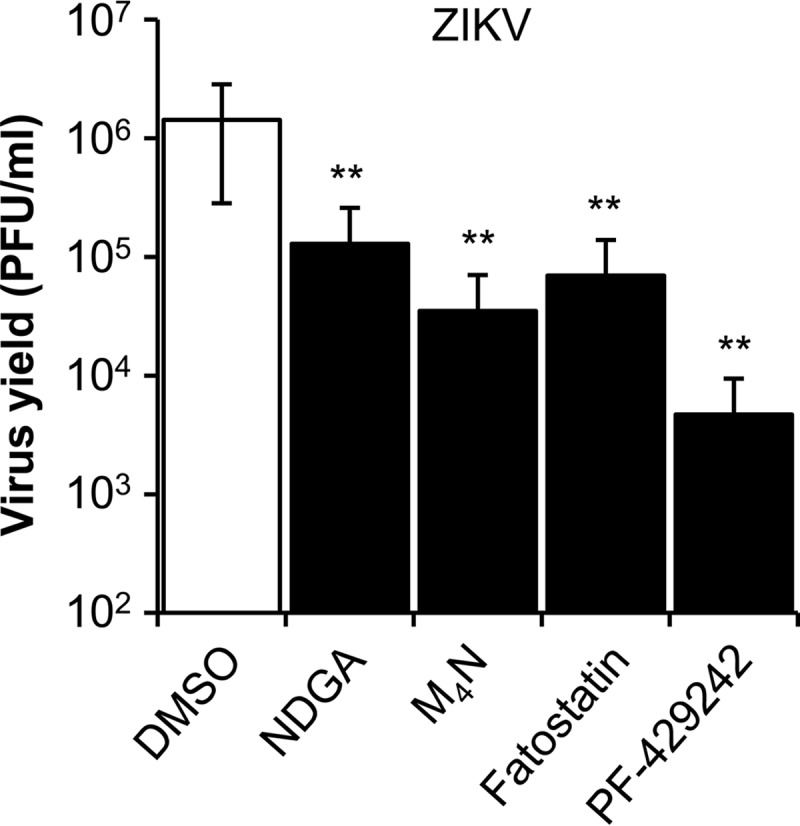

NDGA, M4N, PF-429242, and fatostatin inhibit ZIKV infection.

The current explosive spread of ZIKV propelled us to test whether the drugs used against WNV could be used as well to decrease ZIKV infection. To achieve this goal, the effects of NDGA, M4N, and the two hypolipidemic drugs, PF-429242 and fatostatin, on the multiplication of ZIKV PA259459, isolated from a human patient in Panama in 2015, were examined. As described for WNV, a statistically significant reduction in viral yield was observed for ZIKV when cells were treated with NDGA, M4N, PF-429242, or fatostatin (Fig. 5). These results confirmed the antiviral effects of these compounds, including M4N, against other medically relevant flaviviruses such as ZIKV.

FIG 5.

Reduction of ZIKV infectious particle production in Vero cells treated with NDGA, M4N, fatostatin, or PF-429242. Cells were infected with ZIKV PA259459 (MOI of 1 PFU/cell), treated with 35 μM of each drug, or not (DMSO), and the virus yield in culture supernatant was determined by plaque assay at 24 h p.i. Data are presented as means ± SDs (n = 3). Statistically significant differences between control (DMSO) and drug-treated cells are indicated. **, P < 0.005.

Selectivity indexes of NDGA and M4N against WNV and ZIKV.

The evaluation of the balance between safety and efficacy of drugs is important for drug discovery and development (29), so the selectivity indexes (SIs) of NDGA and M4N were calculated for WNV and ZIKV (Table 1). This index determines the relative effectiveness of the drug in inhibiting viral replication compared to inducing cytotoxicity. SI was determined by quantifying the relation between the 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50; calculated as the concentration that resulted in the reduction of 50% of the amount of cellular ATP) and the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50; calculated as the concentration of drug at which viral infection was inhibited by 50%). Both compounds showed IC50s in the one digit micromolar range for WNV and ZIKV. Since the CC50 of M4N was about 1 order of magnitude higher than that of NDGA (Table 1), the SI of M4N was improved (up to a value of >100) compared to that of NDGA for both WNV and ZIKV.

TABLE 1.

Selectivity indexes of NDGA and M4N against WNV NY99 and ZIKV PA259459

| Compound | CC50a (μM) | WNV NY99 |

ZIKV PA259459 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50b (μM) | SI (CC50/IC50) | IC50 (μM) | SI (CC50/IC50) | ||

| NDGA | 162.1 | 7.9 | 20.5 | 9.1 | 17.8 |

| M4N | 1,071.0 | 9.3 | 115.2 | 5.7 | 187.9 |

CC50 is the concentration that results in the reduction of 50% of the amount of cellular ATP after 24 h of treatment.

IC50 is the concentration of drug at which virus yield (MOI of 1 PFU/cell) is inhibited by 50%. Virus yield was determined by plaque assay 24 h p.i.

DISCUSSION

Due to their inability to perform their own lipid synthesis, flaviviruses are forced to coopt for cellular lipids to complete their replication cycles. Accordingly, pharmacological manipulation of cellular lipid metabolism is rising as an alternative potential strategy to combat these pathogens (7, 8). Along these lines, we have shown that the hypolipidemic compound NDGA and its synthetic derivative M4N exhibit potent antiviral activity against WNV and ZIKV. This antiviral effect of NDGA is consistent with results obtained for DENV and HCV (9, 10). It has to be remarked that the antiviral effects of NDGA or M4N also have been observed against viruses from other viral families, such as herpes simplex virus, human immunodeficiency virus, human papillomavirus, cowpox virus, and vaccinia virus (30–34). Regarding the mechanism behind the antiviral activity of NDGA, in the case of HCV, it was related to an inhibition of the SREBP pathway (10). Consistent with this hypothesis, our results showed that a panel of structurally unrelated inhibitors of the SREBP pathway, such as resveratrol, fatostatin, and PF-429242, also reduced the multiplication of WNV and ZIKV. These results also supported previous studies that point to the importance of the SREBP pathway for infections of flavivirus and hepacivirus (9, 10, 35). The reduction observed for WNV using the SREBP inhibitors resveratrol, fatostatin, and PF-429242 was lower than that observed for NDGA and M4N (compare Fig. 1 and 3), which may suggest that the inhibition of the SREBP pathway is not the only mechanism of action of NDGA and M4N on WNV replication. In the case of the flavivirus DENV, it was proposed that NDGA inhibited viral infection by the following two different means: through viral genome replication reduction and virion assembly inhibition (9). In the present report, quantitative RT-PCR data and immunofluorescence analyses supported that both NDGA and M4N also impaired the replication of the WNV genome. On the contrary, when the effects of NDGA and M4N were directly evaluated on WNV morphogenesis and egress by measuring the production of virus-like particles, no significant reduction was noticed. Therefore, these results support that, in the case of WNV, the inhibitory effects of NDGA and M4N were more likely due to an inhibition of viral genome replication rather than to an impairment of virion morphogenesis. Although we cannot exclude that the drugs also may be acting on entry or viral RNA translation, considering that the entry of flaviviruses into host cells is a very fast process that includes viral fusion within 5 to 10 min p.i. (36, 37) and that in our experimental approach the drugs were added 1 h p.i., it is reasonable to think that their effect is not primarily due to an inhibition of early infection steps. In addition, as no virucidal effect of M4N, and only a slight one of NDGA, was noticed at the highest concentration tested (being markedly lower than the inhibition caused in the viral yield), it is also unlikely that this will be the main mechanism of inhibition of these compounds. The difference in the virucidal ability observed between the two compounds may be because M4N is a methylated derivative of NDGA. In fact, supporting this view, the direct effect of other phenolic compounds on viral particles of the related HCV has been linked to the presence of certain hydroxyl groups within the molecules tested (38).

In our experiments, NDGA and M4N showed similar antiviral activities against WNV and ZIKV at concentrations near to those that can be detected in tissues and plasma of treated animals (39, 40). However, our CC50 values for each compound evidenced that M4N displayed a reduced toxicity in comparison to that of NDGA. In fact, despite the high similarity in the molecular structures of NDGA and M4N, it has been described that the median lethal dose of M4N for mice was greater than 1,000 mg/kg while that of NDGA was only 75 mg/kg (12, 14, 39). Moreover, it has been reported that patients can tolerate higher doses of M4N with minimal side effects (15). Thus, the improved SI of M4N in comparison to that of NDGA may make M4N a more promising antiviral candidate for further evaluation.

In summary, we have described that treatment with NDGA, and its derivative M4N, reduced WNV and ZIKV multiplication. Although further studies of its potential cytotoxic effects in infected hosts are needed, our results together with the clinical safety record of M4N point for the first time to this compound as an interesting candidate for antiviral design against medically relevant flaviviruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, infections, and virus titrations.

All infectious virus manipulations were conducted in biosafety level 3 (BSL3) facilities. Vero (CCL-81) cells (ATCC) were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in Eagle's minimal essential medium (EMEM; Lonza, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin, and 5% fetal bovine serum. HeLa cells stably transfected with a plasmid encoding the last 25 amino acids of the WNV NY99 C protein followed by the sequence of premembrane/membrane (prM) and envelope (E) proteins (HeLa3-WNV cells) were grown in complete culture medium supplemented with 500 μg/ml G418 (18). The origin and passage history of the WNV lineage 1 strain NY99 has been previously described (18, 41). WNV lineage 2 isolate SRB-Novi Sad/12 corresponds to a virus isolated from a goshawk found dead in Serbia in 2012 (42). The American strain of ZIKV PA259459 corresponds to a virus isolated from an infected human in Panama in 2015 and was kindly provided by R. B. Tesh (World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses, Galveston, TX). For infections in liquid medium, the viral inoculum was incubated with cell monolayers for 1 h at 37°C, and then the inoculum was removed and fresh medium containing 1% fetal bovine serum was added. The viral titer was determined by plaque assay in semisolid agarose medium (43). The multiplicity of infection (MOI) used in each experiment was expressed as PFU per cell as is indicated in the corresponding figure legend.

Drug treatments.

NDGA, M4N, zileuton, fatostatin, resveratrol, and BFA were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). PF-429242 was from CliniSciences (Nanterre, France). Unless otherwise specified, drugs were added after the first hour of infection when viral inoculum was replaced by culture medium containing 1% fetal bovine serum. Control cells were treated in parallel with the same amount of drug vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]). Drug toxicity was examined by measuring the cellular ATP content with the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega, Madison, WI).

Antibodies.

Mouse monoclonal antibody 3.67G and rabbit polyclonal antiserum PA1-4139 against the WNV E protein were from Millipore (Temecula, CA) and Thermo Fisher (Rockford, IL), respectively. Mouse monoclonal antibody against β-actin (Sigma) and mouse monoclonal antibody J2 against dsRNA (English & Scientific Consulting, Hungary) were also used. Anti-mouse IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), anti-mouse IgG coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma), and anti-rabbit IgG (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) coupled to horseradish were used as secondary antibodies.

Confocal microscopy.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy were performed as described previously (17, 44). Nuclei were stained with To-Pro-3 (Life Technologies), and images were acquired using a Leica TCS SPE confocal laser scanning microscope and an HCX PL Apo 63×/1.4 oil immersion objective. Fluorescence quantification was performed using ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Enzyme-linked immunodot assay.

The amount of E protein released to the culture medium by HeLa-3-WNV cells was determined using 3.67G monoclonal anti-E antibody and anti-mouse horseradish-coupled secondary antibodies (18, 19).

Western blot.

The amount of E protein within infected cells was determined using the PA1-4139 rabbit antiserum against this protein following a previously published protocol (17).

Quantitative PCR.

Viral RNA was extracted from the supernatant of infected cultures with the SpeedTools RNA virus extraction kit (Biotools B&M Labs, S.A., Madrid, Spain). For quantification of cell-associated viral RNA, supernatants from infected cells were removed and total RNA was extracted from cell monolayers using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies). The amount of viral RNA was determined by real-time fluorogenic reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) according to previously published protocols (44, 45). As a control, the amount of rRNA 18S in RNA samples from cell monolayers was determined as described previously (46). Cell-associated viral RNA copies were normalized to this internal control. The number of viral RNA copies is given as the number of genomic equivalents corresponding to the number of PFU per milliliter by comparison with the amount of RNA extracted from previously titrated samples (47).

Data analysis.

Data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SDs). Analysis of the variance (ANOVA) and Student's test were performed using SPSS 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Bonferroni's correction was applied for multiple comparisons. Statistically significant differences are indicated by one asterisk for a P value of <0.05 or two asterisks (**) for a P value of <0.005.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Calvo for her technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants RTA2013-00013-C04-2014, ZIKA-BIO-2016-01, PLATESA (P2013/ABI-2906), and RTA2015-00009 to J.-C.S. and AGL2014-56518-JIN to M.A.M.-A. T.M.-R. is a recipient of a “Formación de Personal Investigador (FPI)” fellowship from INIA.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martin-Acebes MA, Saiz JC. 2012. West Nile virus: a re-emerging pathogen revisited. World J Virol 1:51–70. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v1.i2.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen LR, Brault AC, Nasci RS. 2013. West Nile virus: review of the literature. JAMA 310:308–315. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saiz JC, Vazquez-Calvo A, Blazquez AB, Merino-Ramos T, Escribano-Romero E, Martin-Acebes MA. 2016. Zika virus: the latest newcomer. Front Microbiol 7:496. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blázquez AB, Saiz JC. 2016. Neurological manifestations of Zika virus infection. World J Virol 5:135–143. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v5.i4.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan TX, Randall G. 2016. Flavivirus modulation of cellular metabolism. Curr Opin Virol 19:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apte-Sengupta S, Sirohi D, Kuhn RJ. 2014. Coupling of replication and assembly in flaviviruses. Curr Opin Virol 9:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin-Acebes MA, Vazquez-Calvo A, Saiz JC. 2016. Lipids and flaviviruses, present and future perspectives for the control of dengue, Zika, and West Nile viruses. Prog Lipid Res 64:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villareal VA, Rodgers MA, Costello DA, Yang PL. 2015. Targeting host lipid synthesis and metabolism to inhibit dengue and hepatitis C viruses. Antiviral Res 124:110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soto-Acosta R, Bautista-Carbajal P, Syed GH, Siddiqui A, Del Angel RM. 2014. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) inhibits replication and viral morphogenesis of dengue virus. Antiviral Res 109:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Syed GH, Siddiqui A. 2011. Effects of hypolipidemic agent nordihydroguaiaretic acid on lipid droplets and hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 54:1936–1946. doi: 10.1002/hep.24619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arteaga S, Andrade-Cetto A, Cardenas R. 2005. Larrea tridentata (Creosote bush), an abundant plant of Mexican and US-American deserts and its metabolite nordihydroguaiaretic acid. J Ethnopharmacol 98:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu JM, Nurko J, Weakley SM, Jiang J, Kougias P, Lin PH, Yao Q, Chen C. 2010. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) and its derivatives: an update. Med Sci Monit 16:RA93–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Q. 2009. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid analogues: their chemical synthesis and biological activities. Curr Top Med Chem 9:1636–1659. doi: 10.2174/156802609789941915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura K, Huang RC. 2016. Tetra-O-methyl nordihydroguaiaretic acid broadly suppresses cancer metabolism and synergistically induces strong anticancer activity in combination with etoposide, rapamycin and UCN-01. PLoS One 11:e0148685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossman SA, Ye X, Peereboom D, Rosenfeld MR, Mikkelsen T, Supko JG, Desideri S. 2012. Phase I study of terameprocol in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. Neuro Oncol 14:511–517. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welsch S, Miller S, Romero-Brey I, Merz A, Bleck CK, Walther P, Fuller SD, Antony C, Krijnse-Locker J, Bartenschlager R. 2009. Composition and three-dimensional architecture of the dengue virus replication and assembly sites. Cell Host Microbe 5:365–375. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin-Acebes MA, Blazquez AB, Jimenez de Oya N, Escribano-Romero E, Saiz JC. 2011. West Nile virus replication requires fatty acid synthesis but is independent on phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate lipids. PLoS One 6:e24970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merino-Ramos T, Blazquez AB, Escribano-Romero E, Canas-Arranz R, Sobrino F, Saiz JC, Martín-Acebes MA. 2014. Protection of a single dose West Nile virus recombinant subviral particle vaccine against lineage 1 or 2 strains and analysis of the cross-reactivity with Usutu virus. PLoS One 9:e108056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin-Acebes MA, Merino-Ramos T, Blazquez AB, Casas J, Escribano-Romero E, Sobrino F, Saiz JC. 2014. The composition of West Nile virus lipid envelope unveils a role of sphingolipid metabolism in flavivirus biogenesis. J Virol 88:12041–12054. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02061-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shao W, Espenshade PJ. 2012. Expanding roles for SREBP in metabolism. Cell Metab 16:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimano H. 2001. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs): transcriptional regulators of lipid synthetic genes. Prog Lipid Res 40:439–452. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7827(01)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang GL, Fu YC, Xu WC, Feng YQ, Fang SR, Zhou XH. 2009. Resveratrol inhibits the expression of SREBP1 in cell model of steatosis via Sirt1-FOXO1 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 380:644–649. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawkins JL, Robbins MD, Warren LC, Xia D, Petras SF, Valentine JJ, Varghese AH, Wang IK, Subashi TA, Shelly LD, Hay BA, Landschulz KT, Geoghegan KF, Harwood HJ Jr. 2008. Pharmacologic inhibition of site 1 protease activity inhibits sterol regulatory element-binding protein processing and reduces lipogenic enzyme gene expression and lipid synthesis in cultured cells and experimental animals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 326:801–808. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.139626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanchet M, Sureau C, Guevin C, Seidah NG, Labonte P. 2015. SKI-1/S1P inhibitor PF-429242 impairs the onset of HCV infection. Antiviral Res 115:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamisuki S, Mao Q, Abu-Elheiga L, Gu Z, Kugimiya A, Kwon Y, Shinohara T, Kawazoe Y, Sato S, Asakura K, Choo HY, Sakai J, Wakil SJ, Uesugi M. 2009. A small molecule that blocks fat synthesis by inhibiting the activation of SREBP. Chem Biol 16:882–892. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhattacherjee P, Boughton-Smith NK, Follenfant RL, Garland LG, Higgs GA, Hodson HF, Islip PJ, Jackson WP, Moncada S, Payne AN, Randall RW, Reynolds CH, Salmon JA, Tateson JE, Whittle BJR. 1988. The effects of a novel series of selective inhibitors of arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase on anaphylactic and inflammatory responses. Ann N Y Acad Sci 524:307–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb38554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salari H, Braquet P, Borgeat P. 1984. Comparative effects of indomethacin, acetylenic acids, 15-HETE, nordihydroguaiaretic acid and BW755C on the metabolism of arachidonic acid in human leukocytes and platelets. Prostaglandins Leukot Med 13:53–60. doi: 10.1016/0262-1746(84)90102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bell RL, Young PR, Albert D, Lanni C, Summers JB, Brooks DW, Rubin P, Carter GW. 1992. The discovery and development of zileuton: an orally active 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor. Int J Immunopharmacol 14:505–510. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(92)90182-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller PY, Milton MN. 2012. The determination and interpretation of the therapeutic index in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 11:751–761. doi: 10.1038/nrd3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen H, Teng L, Li JN, Park R, Mold DE, Gnabre J, Hwu JR, Tseng WN, Huang RC. 1998. Antiviral activities of methylated nordihydroguaiaretic acids. 2. Targeting herpes simplex virus replication by the mutation insensitive transcription inhibitor tetra-O-methyl-NDGA. J Med Chem 41:3001–3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hwu JR, Hsu MH, Huang RC. 2008. New nordihydroguaiaretic acid derivatives as anti-HIV agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 18:1884–1888. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Craigo J, Callahan M, Huang RC, DeLucia AL. 2000. Inhibition of human papillomavirus type 16 gene expression by nordihydroguaiaretic acid plant lignan derivatives. Antiviral Res 47:19–28. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(00)00089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khanna N, Dalby R, Connor A, Church A, Stern J, Frazer N. 2008. Phase I clinical trial of repeat dose terameprocol vaginal ointment in healthy female volunteers. Sex Transm Dis 35:577–582. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31816766af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollara JJ, Laster SM, Petty IT. 2010. Inhibition of poxvirus growth by terameprocol, a methylated derivative of nordihydroguaiaretic acid. Antiviral Res 88:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uchida L, Urata S, Ulanday GEL, Takamatsu Y, Yasuda J, Morita K, Hayasaka D. 2016. Suppressive effects of the site 1 protease (S1P) inhibitor, PF-429242, on Dengue virus propagation. Viruses 8:46. doi: 10.3390/v8020046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Schaar HM, Rust MJ, Chen C, van der Ende-Metselaar H, Wilschut J, Zhuang X, Smit JM. 2008. Dissecting the cell entry pathway of dengue virus by single-particle tracking in living cells. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000244. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nour AM, Li Y, Wolenski J, Modis Y. 2013. Viral membrane fusion and nucleocapsid delivery into the cytoplasm are distinct events in some flaviviruses. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003585. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calland N, Sahuc ME, Belouzard S, Pene V, Bonnafous P, Mesalam AA, Deloison G, Descamps V, Sahpaz S, Wychowski C, Lambert O, Brodin P, Duverlie G, Meuleman P, Rosenberg AR, Dubuisson J, Rouille Y, Seron K. 2015. Polyphenols inhibit hepatitis C virus entry by a new mechanism of action. J Virol 89:10053–10063. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01473-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lambert JD, Meyers RO, Timmermann BN, Dorr RT. 2001. Pharmacokinetic analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography of intravenous nordihydroguaiaretic acid in the mouse. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl 754:85–90. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4347(00)00592-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park R, Chang CC, Liang YC, Chung Y, Henry RA, Lin E, Mold DE, Huang RC. 2005. Systemic treatment with tetra-O-methyl nordihydroguaiaretic acid suppresses the growth of human xenograft tumors. Clin Cancer Res 11:4601–4609. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lanciotti RS, Roehrig JT, Deubel V, Smith J, Parker M, Steele K, Crise B, Volpe KE, Crabtree MB, Scherret JH, Hall RA, MacKenzie JS, Cropp CB, Panigrahy B, Ostlund E, Schmitt B, Malkinson M, Banet C, Weissman J, Komar N, Savage HM, Stone W, McNamara T, Gubler DJ. 1999. Origin of the West Nile virus responsible for an outbreak of encephalitis in the northeastern United States. Science 286:2333–2337. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrovic T, Blazquez AB, Lupulovic D, Lazic G, Escribano-Romero E, Fabijan D, Kapetanov M, Lazic S, Saiz J. 2013. Monitoring West Nile virus (WNV) infection in wild birds in Serbia during 2012: first isolation and characterisation of WNV strains from Serbia. Euro Surveill 18(44):pii=20622 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin-Acebes MA, Saiz JC. 2011. A West Nile virus mutant with increased resistance to acid-induced inactivation. J Gen Virol 92:831–840. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.027185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Merino-Ramos T, Vazquez-Calvo A, Casas J, Sobrino F, Saiz JC, Martin-Acebes MA. 2015. Modification of the host cell lipid metabolism induced by hypolipidemic drugs targeting the acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase impairs West Nile virus replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:307–315. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01578-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lanciotti RS, Kerst AJ, Nasci RS, Godsey MS, Mitchell CJ, Savage HM, Komar N, Panella NA, Allen BC, Volpe KE, Davis BS, Roehrig JT. 2000. Rapid detection of West Nile virus from human clinical specimens, field-collected mosquitoes, and avian samples by a TaqMan reverse transcriptase-PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 38:4066–4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blazquez AB, Martin-Acebes MA, Saiz JC. 2016. Inhibition of West Nile virus multiplication in cell culture by anti-Parkinsonian drugs. Front Microbiol 7:296. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blazquez AB, Saiz JC. 2010. West Nile virus (WNV) transmission routes in the murine model: intrauterine, by breastfeeding and after cannibal ingestion. Virus Res 151:240–243. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]