Abstract

Latua pubiflora (Griseb) Phil. Is a native shrub of the Solanaceae family that grows freely in southern Chile and is employed among Mapuche aboriginals to induce sedative effects and hallucinations in religious or medicine rituals since prehispanic times. In this work, the pentobarbital-induced sleeping test and the elevated plus maze test were employed to test the behavioral effects of extracts of this plant in mice. The psychopharmacological evaluation of L. pubiflora extracts in mice determined that both alkaloid-enriched as well as the non-alkaloid extracts produced an increase of sleeping time and alteration of motor activity in mice at 150 mg/Kg. The alkaloid extract exhibited anxiolytic effects in the elevated plus maze test, which was counteracted by flumazenil. In addition, the alkaloid extract from L. pubiflora decreased [3H]-flunitrazepam binding on rat cortical membranes. In this study we have identified 18 tropane alkaloids (peaks 1–4, 8–13, 15–18, 21, 23, 24, and 28), 8 phenolic acids and related compounds (peaks 5–7, 14, 19, 20, 22, and 29) and 7 flavonoids (peaks 25–27 and 30–33) in extracts of L. pubiflora by UHPLC-PDA-MS which are responsible for the biological activity. This study assessed for the first time the sedative-anxiolytic effects of L. pubiflora in rats besides the high resolution metabolomics analysis including the finding of pharmacologically important tropane alkaloids and glycosylated flavonoids.

Keywords: Palo brujo, psychoactive plant, scopolamine, UHPLC, metabolomics, Latua publiflora (Griseb) Phil.

Introduction

Natural product's research is very important since they represent a rich source of bioactive compounds as new molecules for drug discovery and development (Atanasov et al., 2015; Waltenberger et al., 2016). However, the knowledge about locally used indigenous traditional medicines is scarce around the world, especially in Europe and America (Vogl et al., 2013; Caceres Guido et al., 2015). Some native plants in particular those belonging to the Solanaceae family (Ramoutsaki et al., 2002), can have strong psychoactive activities which lead to altered states of consciousness (Laderman, 1988; Bourguignon, 1989; Metzner, 1998). Their effects can be classified into hallucinogenic, stimulating, or depressing properties depending on the plant used and the secondary metabolites present in the plant. The native species Latua pubiflora (Griseb) Phill. (Solanaceae family, Figure 1), grows freely in Southern Chile along Cordillera de la Costa from Valdivia to Llanquihue regions (from 38°S to 43°S at 500–900 m height above sea-level). This unique species is the only member of the genus and has an important mystic role in the Mapuche indigenous culture for its putative spiritual, sedative and medicinal benefits (Olivares, 1995). In fact, the popular name of this species is “Latue” (Mapuche language) or “Palo brujo” (Spanish name), which literally means “magical stick.” This species belonging to the Solanaceae family is related chemo-taxonomically to the European poisonous plants Atropa belladonna, Datura stramonium, Hyosciamus niger, and Mandragora spp. used in European and Asian countries since ancient times (Hanuš et al., 2005; Beyer et al., 2009). All mentioned species contain scopolamine and atropine as main alkaloids responsible for their pharmacological properties, including sedation, pain relief and psychoactive effects (Ramoutsaki et al., 2002; Beyer et al., 2009; Soni et al., 2012). Anthropological research in Chile has shown that Solanaceae species were smoked in ancient rituals (Echeverria and Niemeyer, 2013; Echeverria et al., 2014; Carrasco et al., 2015) and within them L. pubiflora (Planella et al., 2016). This species has been consumed in different preparations (e.g., infusions, cigarettes) which can cause sedation, mouth dryness, fever, pupillary dilation, delirium, and convulsions (Olivares, 1995) depending on the doses used. L. pubiflora is indeed used by Mapuche medicine men to induce sedation, to reach a trance state or mystical experience and also as piscicide. Previous studies have identified the tropane alkaloids atropine and scopolamine in the fruits and leaves of this shrub (Silva and Mancinelli, 1959; Brawley and Duffield, 1972) and more recently, the presence of 3-α-cinnamoiloxytropane and apoatropine has been reported but the elucidation was tentative and the structures were reported only by using gas chromatography coupled to low resolution mass spectrometry (Muñoz and Casale, 2003). Since the herbal tea of this plant contained several alkaloids and flavonoids (Echeverria and Niemeyer, 2012), in this study two different partitions were prepared to test the alkaloids and flavonoid enriched extracts in behavioral and pharmacological tests.

Figure 1.

Picture of L. pubiflora collected on November 2011, La union, Valdivia.

In the last few years, technological advances made high resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) the method of choice for the rapid analysis of plants and fruits. The new ultra HPLC machines with ESI or APCI interfaces hyphenated with Q-orbitrap or Q-Tof spectrometers allow the accurate identification of several metabolites such as phenolics acids and flavonoids (Borquez et al., 2016; Cornejo et al., 2016), terpenoids (Dong et al., 2016; Simirgiotis et al., 2016b), and alkaloids (Liu C. M. et al., 2016; Liu Z. H. et al., 2016). The purpose of this study was to establish the psychopharmacological effects of enriched extracts of L. pubiflora by the employment of two well-established behavioral paradigms in the rodent model: the elevated plus-maze (EPM) and the pentobarbital-induced sleeping test. The EPM is a behavioral task based on the natural aversion of rodents to heights and open spaces (Pellow et al., 1985; Lister, 1990; Carobrez and Bertoglio, 2005). An increment in the number of entries and/or time spent in the open arms of the maze reflects an anxiolytic effect whereas a decrease in any of these parameters is considered an anxiogenic response (Rodgers and Cole, 1995; Hogg, 1996). Similarly, the pentobarbital-induced sleeping test is a rodent model to assess potential sedative effects (Lovell, 1986a,b). Behavioral pharmacology studies in this work were followed by an assessment of L. pubiflora effects on [3H]flunitrazepam binding by using a rat cortical membrane preparation.

In addition, and following our research program on Chilean flora metabolomics (Simirgiotis et al., 2015, 2016c; Borquez et al., 2016) we have performed the full UHPLC Orbitrap HR-MS metabolome analysis of this important native Mapuche species and related the alkaloid and flavonoids profiles with the ethnopharmacological activity. Our results provide evidence for sedative and anxiolytic properties of L. pubiflora and its psychoactive metabolomics for the first time.

Materials and methods

Drugs and reagents

Reagent grade ethanol (ETOH), methanol (MeOH), chloroform, ethyl acetate (EtOAc) and HPLC grade water were obtained from Merck KGaA, (Darmstadt, Germany). Flumazenil (Lanexat®), diazepam (Valium®) clonazepam (Klonopin™) were from Hoffmann-La Roche Inc., [3H]-methyl-flunitrazepam 60-85Ci/mmol were purchased from ARC American Radiolabeled Chemicals Inc. Saint Louis, MO, Trizma® Base 99.9% (Tris [Hydroxymethyl] aminomethane) Sigma-Aldrich Saint Louis, MO. HPLC standards, (rutin, quercetin, isorhamnetin, scopoletin, citric acid, kaempferol-3-O-rutinose, isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, atropine and scopolamine all standards with purity higher than 95% by HPLC) were purchased either from Sigma Aldrich (Saint Louis, Mo, USA), ChromaDex (Santa Ana, CA, USA), or Extrasynthèse (Genay, France).

Plant material

The plant material used in the present study was collected during two summers (December 2010 and 2011) in a location 5 km from Parque Nacional Alerces Costero (400 10′, 22.5″ S, 730 26′ 30.5″ W), Valdivia, Chile. Aerial parts and flowers were collected and identified by the botanist Carlos Lehnebach. Leaves and twigs were air dried at room temperature and crushed to powder prior to extraction procedures. A voucher specimen was deposited at the Institute of Pharmacy (voucher number lp1052011), Universidad Austral de Chile.

Experimental animals

Rockefeller male mice, 2 months old from the Animal House at the Instituto de Immunología, Universidad Austral de Chile (UACh) were used. They were maintained on a 12:12 light-dark schedule, in a controlled temperature (21°C), were housed in groups of 8 per polycarbonate cages and received free access to food and water. Animals were transported to the laboratory from the animal house 24 h prior to the experimental session in order to their adaptation. The experiments were achieved between 12 and 17 h. Animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under pentobarbital anesthesia or CO2 gas. All behavioral procedures were approved by ethical commission of the University Austral de Chile, UACh- DID S2001-67.

Alkaloids-enriched extract (ALK)

In order to extract all compounds present in the plant, the plant material was extracted with acidified solvent. Thus, the alkaloid-rich extract (ALK) was obtained from 500 g of L. pubiflora chopped leaves using EtOH/HCl, 1% v:v (3 × 1 L) for 24 h. The extract was filtered yielding after evaporation under reduced pressure a syrupy green residue, the residue was later re-suspended in water (0.5 L). Precipitated lipids and chlorophyll were filtered off. The pH of the solution was increased to pH 10-11 using NH4OH and then CHCl3 was added (4 times × 300 mL) in order to obtain free alkaloids. The chloroform extracts were combined and evaporated under vacuum and freeze dried to yield 3.0 g of dry extract (0.6% yield w/w) which was suspended in Tween- 80 −10% for further experiments.

Non-alkaloid (NON-ALK) extract and isolation of scopoletin

Once the alkaloids were extracted, the remaining aqueous solution was neutralized to pH 7 with NaHCO3 and repeatedly extracted with EtOAc (4 times × 300 mL). The extracts showed no major differences on thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and were combined and evaporated under vacuum to a small volume (50 mL). The absence of alkaloids was confirmed using the Draggendorf reaction in TLC assay and HPLC study. A portion (15 mL) was dried and suspended (0.5 g) in Tween- 80 −10% for the biological assays. The remaining concentrated solution (35 mL) was precipitated, and then filtered to yield a white amorphous powder which was crystallized on MeOH in order to obtain a pure product (65 mg). Direct comparison with a standard sample and spectroscopic analysis (IR, UV, 1H-NMR and mass spectra, please see Supplementary Material, Table S1) allowed us to identify the isolated compound as the coumarin scopoletin (Simirgiotis et al., 2013).

UHPLC-PDA-HR-MS

The alkaloid and non alkaloidal partition extracts from leaves of L. pubiflora were analyzed for organic compounds using UHPLC coupled with high resolution mass spectrometry. Approximately 5 mg of each of the dried material dissolved in 2 mL of ultrapure water, with sonication for 2 min and filtered (PTFE filter, Merck) and 10 microliters were injected in the UHPLC instrument for UHPLC-MS analysis. A Thermo Scientific Ultimate 3000 RS UHPLC system controlled by Chromeleon 7.2 Software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, Germany) hyphenated with a Thermo high resolution Q-Exactive focus mass spectrometer (Thermo, Bremen, Germany) were used for analysis. All other conditions and parameters were set as previously reported (Simirgiotis et al., 2016b). Liquid chromatography was performed using an UHPLC C18 column (Acclaim, 150 mm × 4.6 mm ID, 2.5 μm, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) operated at 25°C. The detection wavelengths were 254, 280, and 320 nm and PDA recorded from 200 to 800 nm for peak characterization. Mobile phases were 1% formic aqueous solution (A) and acetonitrile (B). The gradient program (time (min), % B) was: (0.00, 5); (5.00, 5); (10.00, 30); (15.00, 30); (20.00, 70); (25.00, 70); and 12 min for column equilibration before each injection. The flow rate was 1.00 mL min−1, and the injection volume was 10 μL. Standards and extracts dissolved in methanol were kept at 10°C during storage in the auto-sampler (Simirgiotis et al., 2016c). The Spectrometer and HESI II parameters were optimized as previously reported (Simirgiotis et al., 2016c). For the quantification of atropine and scopolamine all measurements were done in triplicate (n = 3). For the recovery experiments of these compounds, known amounts of standards (stock solutions of 0.5 mg/mL) were added to 50 g of the plant matrix and the spiked sample processed using the same methods described above, in triplicate. The amount of the tested compounds were then measured and the percent ratio between the spiked and non-spiked (set as zero level) sample was calculated. The measured amounts in relation to the theoretically present ones were expressed as percent of recovery. The obtained recovery was 115.12 ± 1.68 and 98.3 ± 0.98% (mean ± RSD) for atropine and scopolamine, respectively.

Grouping and dosing of animals

Rockefeller mice maintained on a 12:12 light-dark schedule, in a controlled temperature (21°C). In the behavioral assessment, all testing performed at 150 mg/kg. For the pentobarbital sleeping test, mice were divided into six groups (n = 10), which included three test groups treated with the different extracts with its vehicle as control. All drugs were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.). Extracts were administered 30 min prior to pentobarbital exposure 40 mg/kg. The three test groups received an injection of 150 mg/kg of the ALK extract, 150 mg/kg of the NON-ALK extract and the pure isolated compound scopoletin (7.5 mg/kg). The elevated plus-maze test (EPM) was performed using a maze of two open arms with transparent floor, two black arms enclosed by walls (6 cm × 30 cm × 10 cm) opposite to each other, joined by a central black platform (8 cm × 8 cm). Three different groups of mice were considered (10 mice each group): group one treated with diazepam, group two treated with the ALK extract and group three treated with the NON-ALK extract. In all groups the anxiolytic and locomotor activities were evaluated on the maze, after receiving flumazenil at 0.3 mg/kg s.c., 10 min prior to evaluation.

Binding assay

[3H]Flunitrazepam binding assays were performed with cortical membranes from female rats of approximately 2 months old (125–150 g) obtained from Analytical Biological Services, Inc. (Wilmington, DE). The reaction was initiated by the addition of tissue (20–24 μg protein) to tubes containing 2 nM [3H]flunitrazepam in a final volume of 400 μL of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4. Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 10−4 M clonazepam (Ortiz et al., 1999). Different concentrations of extracts were added to tubes for competition studies. Saturation binding was performed using different concentrations of [3H]Flunitrazepam in the presence of 1.25 × 10−5 g/L of L. pubiflora alkaloid extract. All samples were incubated at 25°C for 40 min. The assay was stopped by rapid filtration of 100 μL of each sample in 24 mm in diameter Millipore AP 40 Glass Fiber prefilters (Millipore Corporation BedFord, MA) in a Millipore manifold (Millipore Corporation BedFord, MA) followed by two - 2.5 mL ice cold buffer washes. Radioactivity of the dried filters was quantified in a Beckman LS 6000 counter with 5 mL of EcoLume scintillation cocktail. Results are shown as percentage of total binding.

Behavioral assessment

In order to determine the experimental dose of the extract, we conducted a dose-response curve in which animals received 800 mg/kg of the ALK extract, and death was induced approximate 5 min after the injections (data not shown). Convulsions were induced at 400 mg/kg i.p. (data not shown). In contrast, 200 mg/kg of the extract induced excitatory effects. Hyperactivity was evident, which caused difficulty in the handling of mice. Therefore, we determined that 150 mg/kg i.p. produced a stable response during a 1 h observation period. Therefore, all behavioral testing was done at 150 mg/kg (i.p.).

Pentobarbital-induced sleeping test

Mice were divided into six groups (n = 10), which included three test groups treated with the different extracts with its vehicle as control. All drugs were injected intraperitoneally. Extracts were administered 30 min prior to pentobarbital exposure 40 mg/kg (i.p.). The onset of sleep (or latency time, the time elapsed between injection of pentobarbital and loss of the righting reflex) and sleeping time (lapse between loss and the recovery of righting reflex) was registered according to Matsumoto et al. (1997). The three test groups received an i.p. injection of 150 mg/kg of the ALK extract, 150 mg/kg of the NON-ALK extract and 7.5 mg/kg i.p. of the isolated compound scopoletin (in the same concentration found in the ALK extract). The control groups were injected with vehicle (10% Tween 80).

Elevated plus-maze (EPM) test

The elevated plus-maze test was performed according to Maruyama et al. (1998). It consisted of two open arms with transparent floor (6 cm × 30 cm), two black arms enclosed by walls (6 cm × 30 cm × 10 cm) arranged in a way that one pair of identical arms were opposite to each other, joined by a central black platform (8 cm × 8 cm). The apparatus was raised to a height of 40 cm above the floor and located in a room with black walls and floor, illuminated by fluorescent light (40 W). The experimental session was registered by a camera linked to a monitor and a video-recorder in an adjacent room, for further analysis by testers unaware of the treatment conditions.

Three groups of 10 mice were used, a control group (NaCl 0.9%), an extract group (150 mg/Kg of extract i.p.) and a reference group (diazepam 1 mg/Kg i,p). EPM behavior was registered 30 min after dosing. At the beginning of the test, each mouse was individually placed onto the central platform facing a closed arm, and the behavior was recorded during a 5 min session. The criterion for an arm entry was defined as four paws into a given arm. In another set of experiments: diazepam, ALK and NON-ALK treated mice received flumazenil at 0.3 mg/kg s.c., 10 min prior to evaluation of anxiolytic and locomotor activity on the maze following (Kuribara et al., 1998).

Statistical analysis

Significance was measured using one-way ANOVA. Whenever appropriate, Student's t-test or χ2 were also employed. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was attained at p ≤ 0.05. Saturation and inhibition curves were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4 software (version 4.03, GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA).

Results

Identification of secondary metabolites in L. pubiflora

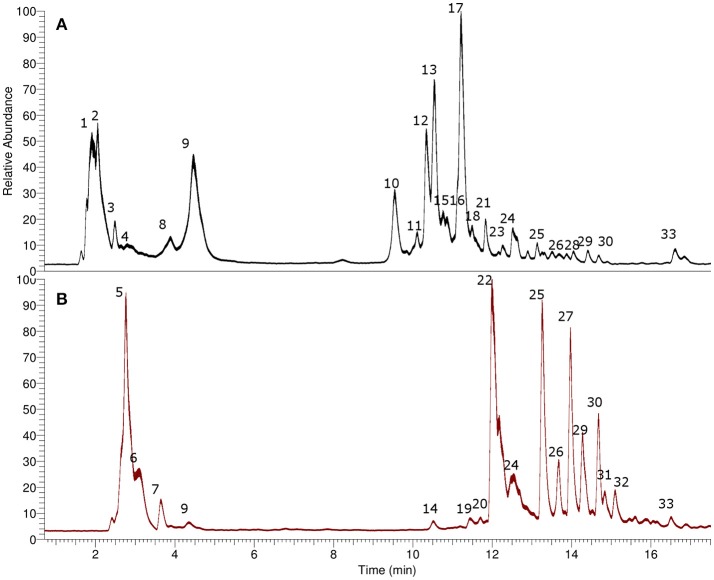

Several compounds including tropane alkaloids, phenolic acids and flavonoids were identified (Table 1) by means of high resolution mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Q-OT-MS), and the UHPLC-TIC chromatogram is depicted in Figure 2. For the tropane alkaloids the retention times of the major components were 11.21 min. for atropine, and 10.34 min. for scopolamine. The contents per g dry weight of the plant L. pubiflora were determined by HPLC to be 344 ± 6.32 μg for scopolamine, 1260 ± 15.24 μg for atropine and 646.8 ± 18.85 μg of scopoletin. The major tropane alkaloids -scopolamine and atropine- were present in 5.7 and 21%, respectively, in the ALK extract used for pharmacological experiments (see below). The coumarin scopoletin was isolated (see Experimental) and its structure obtained by spectroscopic methods (see Supplementary Material) and resulted the major component of the NON-ALK extract (3.90 g). Below is the detailed explanation of the accurate mass identification (Table 1). Several examples of structures and full MS spectra are shown in Supplementary Material (Figures S2).

Table 1.

UV maxima and high resolution Q-Orbitrap MS-MS data and formulas for the metabolites identified in L. pubiflora extracts.

| Peak # | Retention time | Uv max | Tentative identification | Molecular formula [M-H]−or [M+H]+ | Theoretical mass | Measured mass | Accuracy (δppm) | Other ions (MS-MS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.89 | – | Tropine | C8H16NO | 142.12319 | 142.12312 | −0.49 | 124.11265 C8H14N (deshidrotropine) |

| 2 | 2.05 | – | 6-hydroxy-3-O-acetyl tropine | C10H18NO3 | 200.12867 | 200.12935 | 3.39 | 140.10771 C8H14NO (hydroxydeshydroytropine) |

| 3 | 2.51 | – | 3-Acetamidopentoate | C7H12NO3 | 158.08227 | 158.08160 | −4.23 | |

| 4 | 2.53 | 220-285-330 | Hygrine | C8H16NO | 142.12319 | 142.12309 | −0.70 | |

| 5 | 2.76 | 235-287-345 | Scopoletin* | C10H7O4 | 191.03498 | 191.03465 | −1.72 | |

| 6 | 2.94 | – | Quinic acid | C7H11O6 | 191.05611 | 191.05559 | −2.72 | |

| 7 | 3.72 | 230 | Citric acid* | C6H7O7 | 191.01936 | 191.01863 | 3.84 | |

| 8 | 3.88 | – | 3-O-Acetyl-tropine | C10H18NO2 | 184.13375 | 184.13419 | 2.38 | 124.11275, C8H14N (deshidrotropine) |

| 9 | 4.46 | – | 7-hydroxy-3-O-acetyl tropine | C10H18NO3 | 200.12867 | 200.12924 | 2.84 | 140.10771 (hydroxydeshydroytropine) |

| 10 | 9.54 | – | Scopine | C8H14NO2 | 156.10245 | 156.10236 | −0.57 | 138.09196, C8H14NO(deshydroscopine) |

| 11 | 10.30 | – | 3α-Apotropoyloxytropane | C17H22NO2 | 272.16505 | 272.16617 | 4.11 | 124.11262 (C8H14N, dehydrotropane) |

| 12 | 10.51 | – | 7-Hydroxyhyoscyamine | C17H24NO4 | 306.16998 | 306.17209 | 7.56 | 140.10768 (C8H14NO, dehydrated tropane) |

| 13 | 10.34 | – | Scopolamine* | C17H22NO4 | 304.15640 | 304.15488 | 156.10229 (scopine, C8H14NO2), 138.09167 (dehydrated scopine, C8H12NO) | |

| 14 | 10.55 | 220-285-330 | Caffeoyl-glucoside* | C15H15O9 | 341.08781 | 341.08795 | 0.41 | 161.0368, 133.02886 |

| 15 | 10.81 | – | Norhyoscyamine | C16H22NO3 | 276.15997 | 276.16180 | 6.62 | |

| 16 | 10.93 | – | Littorine | C17H22NO3 | 276.15942 | 276.16092 | 5.42 | |

| 17 | 11.21 | – | Atropine* | C17H24N O3 | 290.17758 | 290.17507 | 8.65 | 124.11280 (deshidrotropine, C8H14N) |

| 18 | 11.24 | – | 6-hydroxyhyoscyamine | C17H24NO4 | 306.17209 | 306.16998 | 6.87 | 140.10736 (C8H14NO, dehydrated 6-hydroxy-tropane) |

| 19 | 11.71 | 205-300-324 | Feruloylquinic acid* | C17H19O9 | 367.10236 | 367.10342 | 2.90 | 191.05548, 173.08142 |

| 20 | 11.92 | 197-290-322 | Feruloyl-caffeoylquinic acid | C26H25O12 | 529.13405 | 529.13452 | 0.88 | 173.08174 |

| 21 | 11.83 | – | 6,7-dihydroxy-3-tigloyloxytropane | C13H22NO4 | 256.15488 | 256.15576 | 3.43 | |

| 22 | 12.00 | 220-301-332 | Chlorogenic acid* | C16H17O9 | 353.08746 | 353.08777 | 0.31 | 707.18060, 177.01869 |

| 23 | 12.45 | 280 | 6,7-dihydroxyhyoscyamine | C17H24NO5 | 322.16739 | 322.16490 | 7.72 | 156.10223 (C8H14NO2, dehydrated 6,7-hydroxy-tropane) |

| 24 | 12.86 | – | 4,6-dihydroxyhyoscyamine | C17H24NO5 | 322.16730 | 322.16490 | 7.44 | 643.3393 ([2M+H]+ 156.10225 (C8H14NO2, 4,6-dihydroxy tropane) |

| 25 | 13.28 | 256-353 | Rutin* | C27H29O16 | 609.14611 | 609.14537 | ||

| 26 | 13.54 | 254-365 | Kaempferol-3-O-rutinose* | C27H29O15 | 593.15070 | 593.15010 | 1.01 | 285.04013 (kaempferol) |

| 27 | 13.97 | 256-353 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside* | C22H21O12 | 477.10385 | 477.10273 | −2.17 | 315.05093 (isorhamnetin) 300.02771 |

| 28 | 13.14 | – | 6,7-dihydroxy-3-hydroxytigloyloxytropane | C13H24NO5 | 274.16545 | 274.16376 | −6.16 | |

| 29 | 220-282 | Aposcopolamine | C17H2oNO3 | 286.14432 | 286.14569 | 4.7 | ||

| 30 | 14.68 | 256-353 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-galactoside | C22H21O12 | 477.10385 | 477.10382 | 0.06 | 300.02771 |

| 31 | 14.72 | 254-354 | Isorhamnetin-3-O-rhamnoside | C22H21O11 | 461.10894 | 461.10892 | −0.04 | 177.01855 |

| 32 | 15.06 | 256-353 | Rhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | C22H21O12 | 477.10385 | 477.10367 | −0.37 | 315.05093 (rhamnetin) 300.02798, 271.02490 |

| 33 | 16.51 | 255-355 | Isorhamnetin* | C16H11O7 | 315.05106 | 315.04993 | 3.57 |

Compounds identified by co-elution with authentic standards.

Figure 2.

UHPLC chromatograms (TIC). (A) Alkaloid-rich extract, (B) Non alkaloid extract.

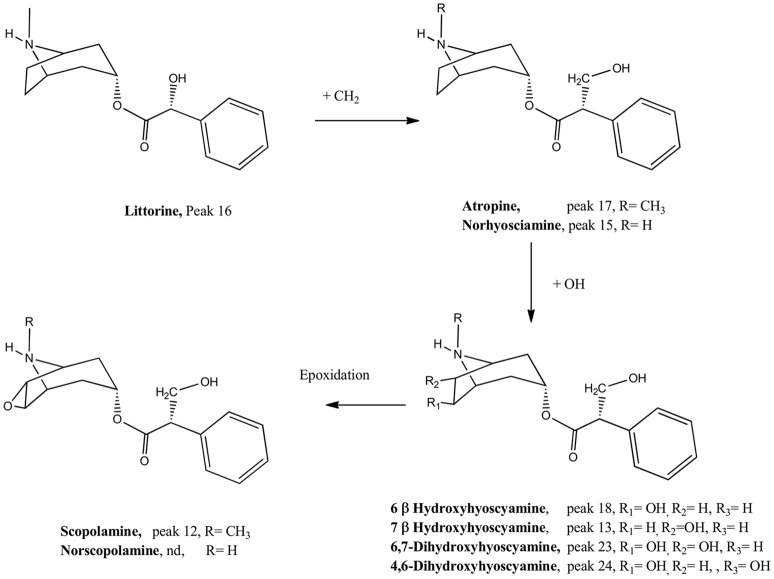

Tropane alkaloids

Peak 1 with a pseudomolecular [M+H]+ ion at m/z: 142.12319 and showing a MS2 ion at m/z: 124.11265 was identified as tropine (C8H16NO) (El Bazaoui et al., 2011), while peak 2 showing an ion at m/z: 200.12867 was identified as its derivative 6-hydroxy-3-O-acetyl tropine. This identification was supported by the loss of an acetyl moiety from the parent compound at m/z: 140.10771 (C8H14NO). Peak 9 with a similar ion (200.12867) was identified as its isomer 7-hydroxy-3-O-acetyl tropine, while peak 8 was identified as 3-O-acetyl-tropine (C10H18NO2), this peak showing also a loss of an acetyl group at m/z: 124.11275, C8H14N (deshidrotropine). Peak 3 was identified as 3-acetamidopentoate (C7H12NO3) and peak 4 as the coca leaves marker hygrine (C8H16NO) (Rubio et al., 2014). Peak 10 was identified as scopine (C8H14NO2). This compound produced a diagnostic MS2 ion at 138.09196 (deshydroscopine) (El Bazaoui et al., 2011). Peak 11 was identified as 3α-apotropoyloxytropane (272.16617) (El Bazaoui et al., 2011) with MS2 fragment at m/z: 124.11262 (C8H14N, dehydrotropane).This compound was previously reported based on GC-MS (Muñoz and Casale, 2003) of an alkaloid extract of L. pubiflora. Peak 13 with a [M+H]+ ion at m/z: 304.15488 was identified as scopolamine (C17H22NO4) previously reported in this plant (Silva and Mancinelli, 1959; Brawley and Duffield, 1972) and producing a diagnostic tropane fragment at m/z: 156.10229 (scopine, C8H14NO2). Peaks 12 and 18 were identified as the derivatives 7-hydroxyhyoscyamine and 6-hydroxyhyoscyamine (C17H24NO4) yielding both a dehydrated tropane fragment at m/z: 140.10768 (C8H14NO). Peak 15 with a [M+H]+ ion at m/z: 276.16180 was identified as Norhyoscyamine (C16H22NO3) (Al Balkhi et al., 2012). Peak 16 was identified as the hyoscyamine precursor littorine (C17H22NO3) (Al Balkhi et al., 2012) and peak 17 as atropine (C17H24N O3) also previously reported (Brawley and Duffield, 1972) and producing a deshidrotropane unit at m/z: 124.11280. Figure 3 shows a biosynthetic relationship among the compounds mentioned and full MS spectra and structures is depicted in the Supplementary Material. Peak 21 was identified as 6,7-dihydroxy-3-tigloyloxytropane (C13H22NO4) (El Bazaoui et al., 2011). Peaks 23 and 24 were tentatively identified as the dihydroxylated derivatives of hyosciamine: 6,7-dihydroxyhyoscyamine and 4,6-dihydroxyhyoscyamine, respectively, producing both a dehydrated 6,7-hydroxy-tropane fragment at m/z: 156.10225 (C8H14NO2). Finally, Peaks 28 and 29 with a [M+H]+ ions at 274.16376 and 286.14569 were identified as 6,7-dihydroxy-3-hydroxytigloyloxytropane (C13H24NO5) and aposcopolamine (C17H2oNO3) respectively (El Bazaoui et al., 2011). Figure 3 shows biosynthetic relationships between the main compounds detected.

Figure 3.

Biosynthetic relationship between the compounds detected. Nd. compound not detected.

Phenolic acids and coumarins

Peak 5 with a [M-H]− ion at m/z: 191.03465 was identified as scopoletin (C10H7O4) as reported (Simirgiotis et al., 2013). Peak 6 was identified as quinic acid (C7H11O6) and peak 7 as citric acid (C6H7O7). Peak 14 with a pseudomolecular anion at m/z: 341.08795 was identified as caffeoyl-glucoside (C15H15O9) (Simirgiotis et al., 2016b) based on UV maxima and MS fragments. Peaks 19, 20, and 22 with pseudomolecular anions at m/z: 367.10342, 529.13405, and 353.08777 were identified as the antioxidant phenolic acids: feruloylquinic acid, feruloyl-caffeoylquinic acid and chlorogenic acid, (Simirgiotis et al., 2016b) respectively.

Flavonoids

Peak 25 with a [M-H]− ion at m/z: 609.14611 was assigned as rutin (C27H29O16) UV max 254–354 nm) (Brito et al., 2014) while peak 26 with a [M-H]− ion at m/z 593.15010 producing a kaempferol aglycone at m/z: 285.04013 was identified as kaempferol-3-O-rutinose (C27H29O15, UV max: 254–365 nm) (Simirgiotis et al., 2016b). In the same manner, peaks 27, 30 and 32 all with full MS anions at around 477.10273 amu, and producing all MSn fragments (315.05093, 300.02798, 271.02490 amu) diagnostics of quercetin methyl ester (rhamnetin or isorhamnetin) were identified as the isomers isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-galactoside and rhamnetin-3-O-glucoside (C22H21O12) (Simirgiotis et al., 2016a) respectively. Peak 31 with a [M-H]− ion at m/z: 461.10892 was identified as isorhamnetin-3-O-rhamnoside (C22H21O11) (Brito et al., 2014) and peak 33 as the aglycone of the mentioned compounds isorhamnetin (C16H11O7).

Sedative-hypnotic effects

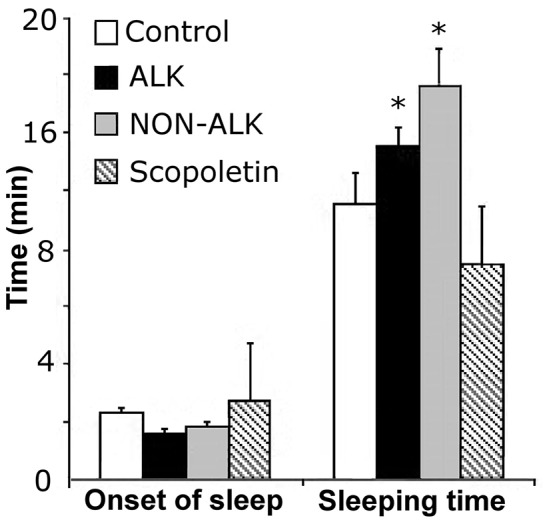

The administration of the alkaloid (ALK) extract of L pubiflora prior to pentobarbital injection, led to a statistically significant increase of the pentobarbital-induced sleeping time, with no modification of sleep latency (Figure 4). The non-alkaloid (NON-ALK) extract of L pubiflora also showed a sedative effect, increasing the sleeping time by approximately 42% compared to the control group. No changes in latency time or sleeping time were found after administration of the major coumarin isolated, scopoletin (Figure 4).

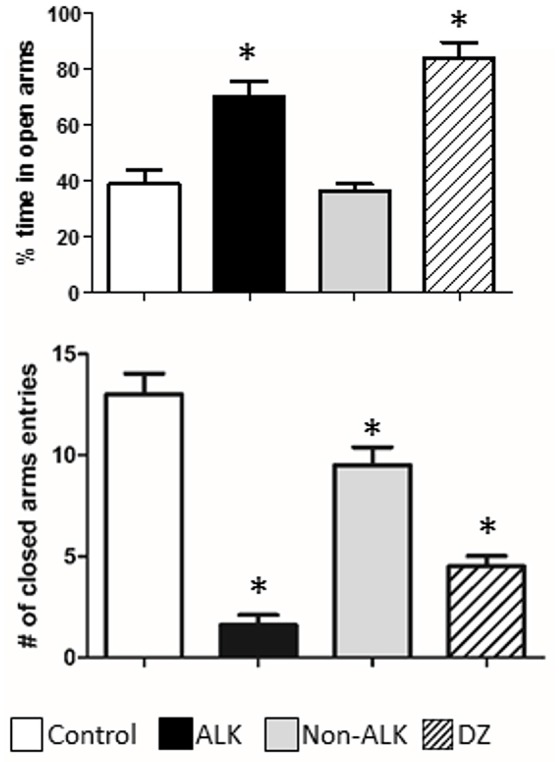

Figure 4.

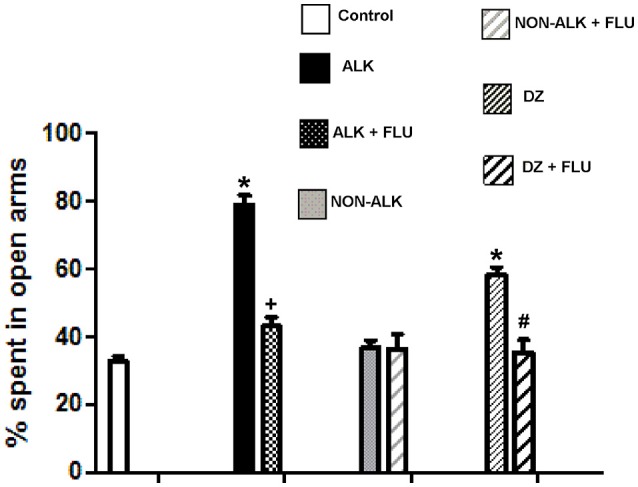

The effect of alkaloid-rich (ALK), non-alkaloid (NON-ALK) extracts, and diazepam (DZ) in the elevated plus maze. Top panel: The ALK extract and DZ 1 mg/Kg i.p. increased the percent (%) time spent in the open arms of the maze. Bottom panel: The ALK (150 mg/Kg ip), NON-ALK, and diazepam (DZ) reduced the number of closed arm entries. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 10/group, *p ≤ 0.05.

Anxiolytic effect

We studied the effect of the ALK and the NON-ALK extracts of L. pubiflora on anxiety-like behavior using the elevated plus-maze test (EPM). The animals that received the ALK extract spent significantly longer time in the open arms of the maze in comparison to that of the control group, as it was also induced by diazepam (DZ) exposure, a well-known GABAA receptor agonist. This effect was not retained by the NON-ALK extract (Figure 5, top panel). By looking at the number of closed arm entries as an indicator of activity levels in this task, we found that the ALK, NON-ALK, and DZ injections at the selected dosages induced a decrease in this parameter (Figure 5, bottom panel). In order to confirm whether the GABAA receptor is involved in open arm behavior, we studied the effects of flumazenil (FLU) (0.3 mg/kg s.c), a high affinity benzodiazepine receptor antagonist. Figure 6 shows that, indeed, FLU counteracted the anxiolytic effect of the alkaloid extract.

Figure 5.

The effect of alkaloid-rich (ALK), non-alkaloid (NON-ALK) extracts, and scopoletin in the pentobarbital-induced sleeping time. The ALK, NON-ALK, and scopoletin had no significant effects in the onset of sleep. The ALK and NON-ALK extracts produced a significant increase in sleeping time when compared to control. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 10/group, *p ≤ 0.05. Onset: latency time.

Figure 6.

The effect of alkaloid-rich (ALK) at 150 mg/kg, non-alkaloid (NON-ALK) at 150 mg/kg extracts, and GABAA receptor modulators in the elevated plus maze. The ALK (150 mg/kg i.p.) extract and diazepam 1 mg/kg i.p. (DZ) increased the % time spent in the open arms of the maze. The ALK (150 mg/kg i.p.) extract plus flumazenil 0,3 mg/Kg s.c. (ALK + FLU) reverted the increase in time spent in the open arms produced by the ALK extract. Similarly, DZ + FLU reverted the increase in time spent in the open arms produced by DZ. Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n = 10/group. *Different from control group (p ≤ 0.05). + Different from ALK group (p ≤ 0.05). #Different from DZ group (p ≤ 0.05). Control: Saline + Tween 20. DZ bar: Diazepam + control, DZ+FLU bar: Diazepam + flumazenil + control.

Binding affinity to GABAA receptor

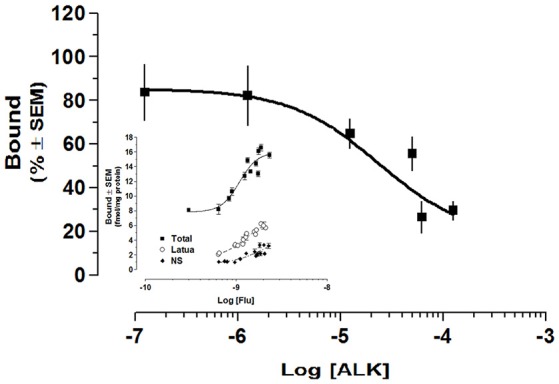

Finally, we performed receptor studies in order to determine the interactions of the alkaloid extract with GABAA receptors. The alkaloid extract of L pubiflora was added from 10−7 to 10−4 mg/mL in presence of 2 nM [3H]flunitrazepam. The results of at least two independent experiments performed in triplicate showed that L. pubiflora ALK extract decreases flunitrazepam binding. The estimated IC50 was 2.365 × 10−5g/L (95% CI 1.6563e-005 to 3.3536e-005). It was not possible to test higher concentrations of the extract due to solubility. The saturation curve of the extract is shown in the Figure 7, which was achieved incubating several concentrations of [3H]Flunitrazepam in presence of 1.25 × 10−5 g/L of L. pubiflora alkaloid extract. As can be seen, the [3H]Flunitrazepam binding was markedly diminished in the range of concentrations that were tested. The apparent Kd could not be estimated as saturation with the extract was not observed.

Figure 7.

The effect of L. pubiflora extract on GABAA-receptor binding assay. Alkaloid extract of L pubiflora was added from 10−7 to 10−4 mg/mL in presence of 2 nM [3H]Flunitrazepam. The estimated IC50 was 2.365 × 10−5g/L. The saturation curve is shown in the insert, which was achieved incubating several concentrations of [3H] Flunitrazepam in presence of 1.25 × 10−5 g/L of L. pubiflora alkaloid extract. Each data point represents a triplicate from at least two separate experiments. ■, total binding; o, Latua (ALK); ♦, non-specific binding.

Discussion

Latua pubiflora has psychotropic properties and has an important mystic role in the Mapuche indigenous culture. People have suffered intoxication looking for a recreational uses of this plant (Olivares, 1995). The toxicity of L. pubiflora is attributed to the high content of tropane alkaloids, mainly atropine and scopolamine, by competitive inhibition of muscarinic receptors (Defrates et al., 2005; Sáiz et al., 2013). Similar effects were observed with Datura compounds (Steenkamp et al., 2004). In our metabolomics analysis we have identified 19 tropane alkaloids (peaks 1–4, 8–13, 15–18, 21, 23, 24, 28, and 29), 8 phenolic acids and related compounds (peaks 5–7, 14, 19, 20, 22, and 29) and 7 flavonoids (peaks 25–27 and 30–33) in extracts of L. pubiflora by UHPLC-PDA-MS, which are the responsible agents for the bioactivity. Both extracts, the alkaloid and non-alkaloid extracts of this plant increased the pentobarbital-induced sleeping time. However, we found that the alkaloid extract of this plant induced an anxiolytic effect in the EPM task, an effect that it could not only be explained by the presence of the tropane derivatives; since scopolamine induces an anxiogenic effect in rats (Rodgers and Cole, 1995; Smythe et al., 1996). In addition, our results have shown that both types of extracts exhibited a reduced locomotor activity in the EPM, suggesting that other mechanisms could be involved. In this regard, the inhibitory GABAA receptor complex is the major target for the more prescribed anxiolytic medicines: the benzodiazepines, which also impaired locomotion by causing ataxia as an important adverse effect. Benzodiazepines act as positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptor, enhancing chloride influx leading to hyperpolarization, for binding to specific pocket on the receptor. Based on this observations, and the evidence that diverse natural products as valerenic acid (Benke et al., 2009) and honokiol (Bernaskova et al., 2015) have shown GABAergic activities, we conducted EPM in the presence of flumazenil, a benzodiazepine antagonist. The partial reversion observed in the open arm-behavior of the ALK-treated mice suggested that the GABAA receptor can mediate, at least in part, these effects. These effects could be attributed to a synergic combination of some of the alkaloids detected: norhyoscyamine, 6-hydroxy-3-O-acetyl-tropine, hygrine, 3-O-acetyl-tropine, 7-hydroxy-3-O-acetyl-tropine, scopine, 3-Apotropoyloxytropane and 7-hydroxyhyoscyamine, besides scopolamine and atropine the most abundant ones. The GABAA receptor complex has more than 10 modulatory binding sites generated by different assembly of its five subunits (Rudolph and Möhler, 2006). Displacement of the [3H] Flunitrazepam binding by the ALK-extract of L. pubiflora to brain membranes is suggestive of the presence of compound(s) present in this extract that compete with the benzodiazepine site at GABAA receptors. we propose that such displacement could reflects subtype specificity (anxiolytic α2/3βγ2) mediated by alkaloid compounds present in this extract or at least, some of them (compounds 1–4, 8–13, 15–18, 21, 23, 24, 28, and 29) can act on the GABAA receptor complex. In addition to those alkaloid compounds, we found several phenolic acids (peaks 14, 19, 20, and 22) and flavonoids (peaks 25–27, 30–32, and 33). These non-alkaloid compounds could be the responsible for the sedative but no anxiolytic activity of the NON-ALK extract because they showed no effect on the EPM. For better insight of specific GABAergic mechanism, more selective methodologies are required, such as the targeting gene encoding the different subunits, or using selective subtype GABAA receptor antagonists (Chagraoui et al., 2016). Those experiments could be interesting to carry out provided we have several isolated candidate molecules for anxiolytic actions from this plant.

In addition to those alkaloid compounds, we isolated and tested the main non-alkaloid compound isolated: scopoletin, which had been identified as an anti-inflammatory agent of Morinda citrifolia (Wang et al., 2002). More recently, scopoletin has been shown to suppress the release of PGE2 and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Kim et al., 2005). Furthermore, several pharmacologic activities have been reported for scopoletin, including antimicrobial, antinociceptive, and hypotensive (Farah and Samuelson, 1992; Erazo et al., 1997). Scopoletin has also been proposed to be involved in the neuropathy induced by Cassava (Ezeanyika et al., 1999). More research is needed to support our findings (isolation of all compounds and testing) but this study is a starting point on the metabolomics and bioactivity of this unique Mapuche species.

Conclusion

The plant showed a plethora of bioactive compounds that were analyzed using high-resolution mass spectrometry, including important alkaloids and flavonoids. The extracts produced an increase of sleeping time and alteration of motor activity in mice that could be in part, attributed to the content of tropane alkaloids, largely known by their antagonist activity on muscarinic receptors. We found that L. pubiflora exhibits sedative and anxiolytic effects that may also be mediated through GABAA receptors. These findings can explain the use of this plant in traditional medicine and religious or mystical ceremonies practiced by Mapuche people.

Author contributions

ES and JO designed the pharmacological experiments, while MR and ES performed the pharmacological tests in rats. JP performed 1HNMR experiments of scopoletin and other spectroscopy experiments and wrote the table. JN and JP prepared the extracts from the plant and isolated scopoletin. JJ performed data analysis and revised data for the manuscript. JB and MS performed the LC-MS analysis. MS, AM, and ES wrote and revised the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Yuji Maruyama for his useful assistance with the elevated plus-maze, Dr. Silvia Erazo for the scopoletin standard sample. We thank Carlos Lehnebach for plant identification and for comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. We thank Nairimer Berríos-Cartagena (UPR) and for their technical assistance and to Dr. Sergio Mora and Dr. Fernanda Cavieres for comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by DID S2001-67, and DID-PEF 2017 (MS) Universidad Austral de Chile, fondequip EQM140002 and the Kellogg's Foundation.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- UHPLC

Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography

- PDA

Photodiode array detector

- GABA

Gamma aminobutyric acid

- ALK

alkaloid

- HESI

heated electrospray

- APCI

Atmospheric pressure chemical ionization.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by DID S2001-67, DID-PEF-2017, Universidad Austral de Chile, fondequip EQM140002 and the Kellogg's Foundation.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphar.2017.00494/full#supplementary-material

References

- Al Balkhi M. H., Schiltz S., Lesur D., Lanoue A., Wadouachi A., Boitel-Conti M. (2012). Norlittorine and norhyoscyamine identified as products of littorine and hyoscyamine metabolism by C-13-labeling in Datura innoxia hairy roots. Phytochemistry 74, 105–114. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atanasov A. G., Waltenberger B., Pferschy-Wenzig E.-M., Linder T., Wawrosch C., Uhrin P., et al. (2015). Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: a review. Biotechnol. Adv. 33, 1582–1614. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benke D., Barberis A., Kopp S., Altmann K. H., Schubiger M., Vogt K. E., et al. (2009). GABA A receptors as in vivo substrate for the anxiolytic action of valerenic acid, a major constituent of valerian root extracts. Neuropharmacology 56, 174–181. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaskova M., Schoeffmann A., Schuehly W., Hufner A., Baburin I., Hering S. (2015). Nitrogenated honokiol derivatives allosterically modulate GABAA receptors and act as strong partial agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 23, 6757–6762. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer J., Drummer O. H., Maurer H. H. (2009). Analysis of toxic alkaloids in body samples. For. Sci. Int. 185, 1–9. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borquez J., Bartolucci N. L., Echiburu-Chau C., Winterhalter P., Vallejos J., Jerz G., et al. (2016). Isolation of cytotoxic diterpenoids from the Chilean medicinal plant Azorella compacta Phil from the Atacama desert by high-speed counter-current chromatography. J. Sci. Food Agric. 96, 2832–2838. 10.1002/jsfa.7451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon E. (1989). Trance and shamanism: what's in a name? J. Psychoactive Drugs 21, 9–15. 10.1080/02791072.1989.10472138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawley P., Duffield J. (1972). The pharmacology of hallucinogens. Pharmacol. Rev. 24, 31–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito A., Ramirez J. E., Areche C., Sepúlveda B., Simirgiotis M. J. (2014). HPLC-UV-MS profiles of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of fruits from three citrus species consumed in Northern Chile. Molecules 19, 17400–17421. 10.3390/molecules191117400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres Guido P., Ribas A., Gaioli M., Quattrone F., Macchi A. (2015). The state of the integrative medicine in Latin America: the long road to include complementary, natural, and traditional practices in formal health systems. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 7, 5–12. 10.1016/j.eujim.2014.06.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carobrez A. P., Bertoglio J. L. (2005). Ethological and temporal analyses of anxiety-like behavior: the elevated plus maze 20 years on. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 29, 1193–1205. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco C., Echeverria J., Ballester B., Niemeyer H. M. (2015). Of pipes and substances: fumatorial customs during the formative period in the desert coast of Atacama (North of Chile). Lat. Am. Antiq. 26, 143–161. 10.7183/1045-6635.26.2.143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chagraoui A., Skiba M., Thuillez C., Thibaut F. (2016). To what extent is it possible to dissociate the anxiolytic and sedative/hypnotic properties of GABA A receptors modulators? Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatr. 71, 189–202. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo A., Salgado F., Caballero J., Vargas R., Simirgiotis M., Areche C. (2016). Secondary metabolites in Ramalina terebrata detected by UHPLC/ESI/MS/MS and identification of parietin as Tau protein inhibitor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:1703. 10.3390/ijms17081303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defrates L. J., Hoehns J. D., Sakornbut E. L., Glascock D. G., Tew A. R. (2005). Antimuscarinic intoxication resulting from the injection of moonflower seeds. Ann. Pharmacother. 39, 173–176. 10.1345/aph.1D536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Q., Qiu L. L., Zhang C. E., Chen L. H., Feng W. W., Ma L. N., et al. (2016). Identification of compounds in an anti-fibrosis Chinese medicine (Fufang Biejia Ruangan Pill) and its absorbed components in rat biofluids and liver by UPLC-MS. J. Chromatogr. B 1026, 145–151. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria J., Niemeyer H. M. (2012). Alkaloids from the native flora of Chile: a review. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plant. Med. Arom. 11, 291–305. Available online at: http://www.cienciaymemoria.cl/anillo/pdf/publicaciones/ARTICLE%2002_ECHEVERRIA_NIEMEYER_2012a.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria J., Niemeyer H. M. (2013). Nicotine in the hair of mummies from San Pedro de Atacama (Northern Chile). J. Archaeolog. Sci. 40, 3561–3568. 10.1016/j.jas.2013.04.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria J., Planella M. T., Niemeyer H. M. (2014). Nicotine in residues of smoking pipes and other artifacts of the smoking complex from an early ceramic period archaeological site in central Chile. J. Arch. Sci. 44, 55–60. 10.1016/j.jas.2014.01.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Bazaoui A., Bellimam M. A., Soulaymani A. (2011). Nine new tropane alkaloids from Datura stramonium L. identified by GC/MS. Fitoterapia 82, 193–197. 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erazo S., García R., Backhouse N., Lemus I., Delporte C., Andrade C. (1997). Phytochemical and biological study of radal Lommatia hirsuta (Proteaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 57, 81–83. 10.1016/S0378-8741(97)00048-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezeanyika L. U., Obidoa O., Shoyinka V. O. (1999). Comparative effects of scopoletin and cyanide on rat brain, 1: histopathology. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 53, 351–358. 10.1023/A:1008096801895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah M., Samuelson G. (1992). Pharmacologically active phenylpropanoids from Senra incana. Planta Med. 58, 14–18. 10.1055/s-2006-961380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanuš L. O., Řezanka T., Spížek J., Dembitsky V. M. (2005). Substances isolated from Mandragora species. Phytochemistry 66, 2408–2417. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg S. (1996). A review of the validity and variability of the elevated plus-maze as an animal model of anxiety. Pharmacol. Biochemi. Behav. 54, 21–30. 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02126-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I. T., Park H. J., Nam J. H., Park Y. M., Won J. H., Choi J., et al. (2005). In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects of the methanol extract of the roots of Morinda officinalis. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 57, 607–615. 10.1211/0022357055902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuribara H., Stavinoha W. B., Maruyama Y. (1998). Behavioural pharmacological characteristics of honokiol, an anxiolytic agent present in extracts of Magnolia bark, evaluated by an elevated plus-maze test in mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 50, 819–826. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1998.tb07146.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laderman C. (1988). Wayward winds: Malay archetypes and theory of personality in the context of shamanism. Soc. Sci. Med. 27, 799–810. 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90232-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R. G. (1990). Ethologically-based animal model of anxiety disorder. Pharmacol. Ther. 46, 321–340. 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90021-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. M., Hua Z. D., Bai Y. P. (2016). Classification of opium by UPLC-Q-TOF analysis of principal and minor alkaloids. J. For. Sci. 61, 1615–1621. 10.1111/1556-4029.13190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. H., Chang S., Guan X. Y., Han N., Yin J. (2016). The metabolites of Ambinine, a benzo c phenanthridine alkaloid, in rats identified by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupoletime-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC/Q-TOF-MS/MS). J. Chromatogr. B 1033, 226–233. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2016.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell D. P. (1986a). Variation in pentobarbitone sleeping time in mice. 2. variables affecting test results. Lab. An. 20, 91–96. 10.1258/002367786780865089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell D. P. (1986b). Variation in pentobarbitone sleeping time in mice. strain and sex differences. Lab. An. 20, 85–90. 10.1258/002367786780865142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama Y., Kuribara H., Morita M., Yuzurihara M., Weintraub S. (1998). Identification of magnolol and honokiol as anxiolytic agents in extracts of Saiboku-to, an oriental herbal medicine. J. Nat. Prod. 61, 135–138. 10.1021/np9702446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K., Kohno S., Ojima K., Watanabe H. (1997). Flumazenil but not FG7142 reverses the decrease in pentobarbital sleep caused by activation of central noradrenergic systems in mice. Brain Res. 754, 325–328. 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)00176-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzner R. (1998). Hallucinogenic drugs and plants in psychotherapy and shamanism. J. Psychoactive Drugs 30, 333–341. 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz O., Casale E. (2003). Tropane alkaloids from Latua pubiflora. Z. Naturforsch. 58, 626–628. Available online at: http://www.znaturforsch.com/ac/v58c/s58c0626.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares J. C. (1995). El Umbral Roto. Santiago, Fondo Matta: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz J. G., Nieves-Natal J., Chavez P. (1999). Effects of valeriana officinalis extracts on [3H]Flunitrazepam binding, synaptosomal [3H]GABA uptake, and hippocampal [3H]GABA release. Neurochem. Res. 24, 1373–1378. 10.1023/A:1022576405534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellow S., Chopin P., File S., Briley M. (1985). Validation of open-closed arm entries in an elevated plus-maze as a measure of anxiety in the rat. J. Neurosci. Meth. 14, 149–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planella M. T., Belmar C. A., Quiroz L. D., Falabella F., Alfaro S. K., Echeverría J., et al. (2016). Towards the reconstruction of the ritual expressions of societies of the early ceramic period in central chile: social and cultural contexts associated with the use of smoking pipes, in Perspectives on the Archaeology of Pipes, Tobacco and other Smoke Plants in the Ancient Americas, eds Eilizabeth S. T., Bollwerk A. (New York, NY: Springer International Publishing; ), 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- Ramoutsaki I. A., Askitopoulou H., Konsolaki E. (2002). Pain relief and sedation in Roman Byzantine texts: mandragoras officinarum, Hyoscyamos niger and Atropa belladonna. Int. Congr. Ser. 1242, 43–50. 10.1016/S0531-5131(02)00699-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers R. J., Cole J. C. (1995). Effects of scopolamine and its quaternary analogue in the murine elevated plus maze test of anxiety. Behav. Pharmacol. 6, 283–289. 10.1097/00008877-199504000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio N. C., Strano-Rossi S., Tabernero M. J., Gonzalez J. L., Anzillotti L., Chiarotti M., et al. (2014). Application of hygrine and cuscohygrine as possible markers to distinguish coca chewing from cocaine abuse on WDT and forensic cases. Foren. Sci. Int. 243, 30–34. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U., Möhler H. (2006). GABA-based therapeutic approaches: GABA A receptor subtype functions. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 6, 18–23. 10.1016/j.coph.2005.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáiz J., Mai T. D., López M. L., Bartolomé C., Hauser P. C., García-Ruiz C. (2013). Rapid determination of scopolamine in evidence of recreational and predatory use. Sci. Just. 53, 409–414. 10.1016/j.scijus.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M., Mancinelli P. (1959). Atropina en Latua pubiflora (Griseb). Phil. Bol. Soc Chil. Quim. 9, 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Simirgiotis M. J., Bórquez J., Neves-Vieira M., Brito I., Alfaro-Lira S., Winterhalter P., et al. (2015). Fast isolation of cytotoxic compounds from the native Chilean species Gypothamnium pinifolium Phil. collected in the Atacama Desert, northern Chile. Ind. Crops Prod. 76, 69–76. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.06.033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simirgiotis M. J., Quispe C., Areche C., Sepulveda B. (2016a). Phenolic compounds in Chilean Mistletoe (Quintral, Tristerix tetrandus) analyzed by UHPLC-Q/Orbitrap/MS/MS and Its antioxidant properties. Molecules 21:245. 10.3390/molecules21030245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simirgiotis M. J., Quispe C., Bórquez J., Areche C., Sepúlveda B. (2016b). Fast detection of phenolic compounds in extracts of easter pears (Pyrus communis) from the Atacama Desert by ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (UHPLC–Q/Orbitrap/MS/MS). Molecules 21:92. 10.3390/molecules21010092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simirgiotis M. J., Quispe C., Bórquez J., Schmeda-Hirschmann G., Avendaño M., Sepúlveda B., et al. (2016c). Fast high resolution orbitrap MS fingerprinting of the resin of heliotropium taltalense Phil. from the Atacama Desert. Ind. Crops Prod. 85, 159–166. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.02.054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simirgiotis M. J., Ramirez J. E., Schmeda Hirschmann G., Kennelly E. J. (2013). Bioactive coumarins and HPLC-PDA-ESI-ToF-MS metabolic profiling of edible queule fruits (Gomortega keule), an endangered endemic Chilean species. Food Res. Int. 54, 532–543. 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.07.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe J. W., Murphy D., Bhanagar S., Timothy C., Costall B. (1996). Muscarinic antagonists are anxiogenic in rats tested in the black-white box. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 54, 57–63. 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02130-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni P., Siddiqui A. A., Dwivedi J., Soni V. (2012). Pharmacological properties of Datura stramonium L. as a potential medicinal tree: an overview. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2, 1002–1008. 10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60014-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp P. A., Harding N. M., Van Heerden F. R., Van Wyk B. E. (2004). Fatal Datura poisoning: identification of atropine and scopolamine by high performance liquid chromatography/photodiode array/mass spectrometry. Forensic. Sci. Int. 145, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl S., Picker P., Mihaly-Bison J., Fakhrudin N., Atanasov A. G., Heiss E. H., et al. (2013). Ethnopharmacological in vitro studies on Austria's folk medicine—an unexplored lore in vitro anti-inflammatory activities of 71 Austrian traditional herbal drugs. J. Ethnopharmacol. 149, 750–771. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltenberger B., Mocan A., Smejkal K., Heiss E. H., Atanasov A. G. (2016). Natural products to counteract the epidemic of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. Molecules 21:807. 10.3390/molecules21060807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. Y., West B. J., Jensen C. J., Nowicki D., Su C., Palu A. K., et al. (2002). Morinda citrifolia (Noni): a literature review and recent advances in Noni research. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 23, 1127–1141. Available online at: http://www.chinaphar.com/article/view/7261/7889 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.