Summary

Dengue viruses (DENV), a group of four serologically distinct but related flaviruses, are the cause of one of the most important emerging viral diseases. DENV infections result in a wide spectrum of clinical disease including dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), a viral hemorrhagic disease characterized by bleeding and plasma leakage. The characteristic feature of DHF is the transient period of plasma leakage and a hemorrhagic tendency. DHF occurs mostly during a secondary DENV infection. Serotype-cross reactive antibodies and mediators from serotype cross-reactive dengue specific T cells have been implicated in the pathogenesis. A complex interaction between virus, host immune response and endothelial cells likely impacts the barrier integrity and functions of endothelial cells leading to plasma leakage. Recently the role of angiogenic factors and the role of dengue virus on endothelial cell transcription and functions have been studied. Insights into the mechanisms that confer protection or cause disease are critical in the development of prophylactic and therapeutic modalities for this important disease.

Keywords: dengue viruses, dengue hemorrhagic fever, plasma leakage, permeability, immune system

Introduction

Dengue remains an important threat to public health worldwide. There has been a significant increase in dengue cases reported to the WHO from approximately 900 cases per year from 1950 to 1959 to over 500,000 cases annually from 1990 to 1999. (1) It is estimated that over 50 million dengue virus (DENV) infections occur annually resulting in 500,000 hospitalizations and over 20,000 deaths. In addition to the known endemic countries in Southeast Asia where DENV infection causes significant mortality, morbidity and economic burden, dengue has become a threat in other areas of the world including the Americas, the Indian subcontinent and Oceania, making dengue one of the most important emerging infectious diseases worldwide. (2–4)

Dengue Viruses

Dengue is caused by infection with dengue viruses which are positive strand viruses belonging to the Flavivirus genus. Dengue viruses are transmitted through mosquito bites. Aedes aegypti is the principal mosquito vector in virus transmission. (5). The genome of DENV encodes 10 different gene products: C (capsid), prM (matrix), E (envelope), and nonstructural proteins including NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5. (6) The E protein interacts with cellular receptor(s) which initiates viral entry. The amino acid sequences of the E proteins determine the antibody neutralizing activity that classifies DENV into 4 serotypes: DENV1, 2, 3 and 4. (5) Nonstructural proteins of DENV function in RNA replication and assembly and in viral protein processing. NS3 is a multifunctional protein with helicase and protease activities. Its serine protease activity requires NS2B as a cofactor. (6) NS5 functions as an S-adenosine methyltransferase and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. In addition to their roles in viral replication, some non-structural proteins also play a role in modifying host immune system. NS2A, NS2B and NS4B have been shown to interfere with type I IFN signaling pathway. (7, 8) NS5 has been demonstrated to induce IL-8 production. (9) NS1 is the only nonstructural protein with a soluble form that can be detected in circulation. (10)

Clinical Dengue

In endemic areas, infections occur early and the majority of children have been infected at least once in the first decade of life. Most primary (i.e. initial) infections in children are clinically inapparent although some may develop undifferentiated fever. Primary infections in older children and adults are more likely to cause dengue fever (DF), a febrile illness accompanied by a combination of non-specific symptoms including headache, retroorbital pain, myalgia and occasionally hemorrhagic manifestations. (11) A minority of patients develop dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), the most severe form of dengue disease. The hallmark of DHF is the presence of plasma leakage which can lead to the loss of intravascular volume and circulatory insufficiency. (11) Significant bleeding is another clinical feature associated with severe disease. Bleeding is common in both DF and DHF; more severe bleeding, particularly bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract, is found more frequently in DHF than in DF. Increased liver enzymes and thrombocytopenia are commonly observed in both DF and DHF cases but are more severe in DHF cases. Table 1 shows the World Health Organization case definitions of DF and DHF. The case definition of DHF is 1) fever, 2) bleeding, 3) thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100,000 cell/cumm, 4) evidence of plasma leakage as indicated by the presence of pleural and/or ascitic fluid or hemoconcentration. (11) DHF patients who have narrow pulse pressure (less than 20 mmHg) or show signs of shock are classified as dengue shock syndrome (DSS). Other severe clinical manifestations including hepatic failure and encephalopathy have been reported in dengue cases. (12–14)

Table 1.

| Dengue Fever (DF) | Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (DHF) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

Probable DF is an acute febrile illness with TWO OR MORE of the following:

and Supportive serology or occurrence at the same location and time as other confirmed cases of dengue. Confirmed DF is a case confirmed by laboratory criteria (serology, viral isolation, viral genome detection). |

DHF case definition (all 4 components must be met)

Defintion of dengue shock syndrome (DSS): DHF cases with documented narrow pulse pressure (< 20 mmHg), hypotension or other signs of shock. |

|

Current clinical classification of dengue illness describes DF and DHF as distinct clinical entities. DF and DHF share certain clinical features including fever, hemorrhagic tendency and, to a certain extent, thrombocytopenia. The clinical feature distinguishing DHF from DF is the presence of plasma leakage in DHF. Hemoconcentration, defined as a 20% increase in hematocrit, is widely used as an indicator of plasma leakage. However, hematocrit readings can be affected by factors other than plasma leakage such as fever, dehydration and hemorrhage. Furthermore, failures to obtain repeated measurements needed to calculate the degree of hemoconcentration often lead to difficulties in classifying dengue cases. Studies employing chest radiographs or serial ultrasonography to detect plasma leakage directly have demonstrated that progressive and significant accumulation of fluid only occurred in a subset of dengue cases (15, 16). The extent of plasma leakage has been shown to correlate with the decline in platelet counts (17). Despite the clinical classification of DF and DHF as distinct entities, they are likely a continuum of the same disease process with divergent outcomes with regard to the perturbation of vascular integrity.

Clinical course of DF and DHF

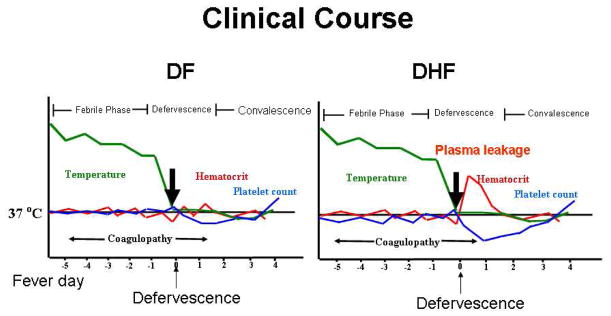

Figure 1 depicts the typical clinical course of patients in DF (a) or DHF (b). Patients with DF or DHF usually present with a history of abrupt onset of high, persistent fever (18). Other clinical manifestations during the febrile phase of the illness include myalgia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. During this period, patients may display varied degrees of hemorrhagic tendencies ranging from small petechiae to nose bleed to bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract. Significant dehydration may also develop at this stage of illness, which may require intravenous fluid treatment. The febrile period can last between 2 and 7 days. Around the time of defervescence, DHF patients develop localized plasma leakage manifested as accumulation of fluid in pleural and abdominal cavities and hemoconcentration. The leakage lasts approximately 48 hours and is followed by a spontaneous and rapid resolution. The extent of plasma leakage varies between individual patients and can lead to intravascular volume depletion requiring fluid resuscitation. In addition, hepatic failure and encephalopathy may develop secondary to prolonged shock. Mortality is usually due to a delay in the recognition and treatment of plasma leakage.

Figure 1. Clinical course of DF and DHF.

An abrupt onset of high, persistent fever is an early manifestation of both DF and DHF. During the febrile phase, patients may develop other signs and symptoms including headache, myalgia and variable degrees of hemorrhagic tendency. Platelet counts decline during this stage, reaching the lowest point around the time of defervescence. During defervescence, some patients develop a transient increase in vascular permeability resulting in leakage of albumin rich fluid in the pleural and abdominal cavities. This is associated with hemoconcentration as indicated by an increase in hematocrit. Evidence of plasma leakage and thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100,000/cumm) are the two criteria differentiating DHF from DF. The plasma leakage usually resolves after 48 hours followed by a convalescence period.

Treatment of dengue

Close observation for signs of bleeding and circulatory compromise and prompt supportive treatment are the mainstay in dengue case management (18). Volume depletion often occurs due to fever, poor oral intake, bleeding, and plasma leakage. In cases with significant dehydration or depleted intravascular volume due to plasma leakage, intravenous fluid treatment with crystalloid solution is needed. Blood transfusion may be needed if hemorrhage is significant. In cases with shock crystalloid fluid (10–20 ml/kg) is administered intravenously to maintain blood pressure. Colloid fluid has been used for resuscitation in shock cases with poor response to crystalloid fluid resuscitation. However, a study has demonstrated that colloid may not be superior to crystalloid fluid for this purpose (19). Intravenous fluid treatment must be carefully adjusted to adequately maintain circulation. Excessive fluid treatment can lead to serious complications such as pulmonary edema and respiratory failure (18).

Risk factors for DHF

Prospective cohort studies in school children have demonstrated an increased risk of DHF in individuals with secondary infection compared to those with primary infection. (20, 21) The risk of developing DHF in secondary versus primary infection varies between studies but is approximately ten fold or more. (4, 20) It is postulated that antibodies elicited by the first (or primary) exposure to one serotype of DENV, rather than protecting against infection by a second dengue virus of a distinct serotype, enhance virus uptake possibly via Fc receptors and promote viral replication. IN VITRO, virus incubated with diluted immune plasma can promote viral replication in monocytes and susceptible cell lines. (22) Enhanced viral replication has been observed in rhesus monkeys that received immune serum prior to virus inoculation. (23)

In addition to host immune status, various gene loci have been reported to be associated with the clinical severity of dengue disease. In connection with T cell immunity, certain HLA class I and class II loci have been linked to DHF while others have been associated with DF. (24) Other genetic polymorphisms reported to be associated with disease severity include TNF-α, Fc receptor, TAPs and DC-SIGN (CD209). (25–27)

Major outbreaks of DHF have followed the introduction of a new strain or new serotype of DENV into an area. This may be due to the immunologic susceptibility of the population to infection by newly introduced viruses. Intrinsic virulence of the viruses may also play a role in determining the disease severity. Outbreaks of DHF in the 1980–90’s in the Americas were associated with the introduction of Southeast Asian strains of D2V which replaced the D2V strains that previously existed in the region. (28) Subsequent studies demonstrated that sera from individuals in the region who had been exposed to DENV-1 exhibited cross-neutralizing activity against American strain of DENV-2 but not the Asian strain. (29, 30) In addition, Asian D2V variants replicated more effectively in primary human cells than American D2V strains IN VITRO. This has been attributed to differences in non-coding as well as coding portions of viral genomes (31, 32). Recent studies have demonstrated that viral NS proteins can interfere with type I IFN signaling and induce cytokine production. (7–9) Whether these NS proteins contribute to the virulence of dengue virus and whether there are differences in genes encoding these proteins of various dengue viral isolates of different virulence await further studies.

Animal models

Understanding the pathogenesis of dengue has been hampered by the lack of animal models. Although non-human primates can be infected with DENV, they do not develop disease. Recent progress has been made in modeling dengue in mice. Studies using mouse-adapted strains of dengue virus and studies using mice genetically deficient in innate or adaptive immunity have demonstrated viral replication and some clinical features resembling dengue disease including the presence of thrombocytopenia (33–35). Immunodeficient mice engrafted with human bone marrow cells and subcutaneously inoculated with dengue virus showed viral replication in various tissues and developed features of DF including fever, thrombocytopenia and skin erythema (36, 37). Similar to human dengue, monocytes/macrophages appeared to be the main cells infected in these models. Infection of endothelial cells has also been reported. Signs of increased vascular permeability have been reported in intestine, liver and spleen in some models (35). The anatomical pattern of plasma leakage in these models does not resemble the pattern observed in DHF in humans (pleural effusion, ascites). Nevertheless, these models may be helpful in studying certain aspects of dengue pathogenesis such as the hematological changes and liver disease, and the role of innate and adaptive immunity in regulating viral replication.

Pathology and pathogenesis

Few studies exist that describe the pathology of DHF. In a study that described pathology findings in 100 fatal dengue cases, diffuse mucosal hemorrhage and serous membrane edema were the two prominent gross findings. (38) Microscopic findings included hemorrhage in various organs and perivascular and interstitial tissue edema. Perivascular mononuclear infiltration and endothelial cell pyknosis were observed in some cases. Subsequent studies have demonstrated dengue antigen in various cell types including monocytes, Kupffer cells, alveolar macrophages, peripheral blood and splenic lymphocytes, and endothelial cells in the liver and the lungs. (39).

Much of the present understanding of DHF pathogenesis is based on information obtained from studies in dengue patients and from IN VITRO models. IN VIVO monocytes/macrophages and lymphocytes are the main cells that are infected with DENV. (39) Some studies have reported antigen staining in hepatocytes and endothelial cells. (39–41) Although not formally demonstrated IN VIVO, dendritic cells are likely to be infected and play a key role in initiating immune response. A C-type lectin molecule expressed by dendritic cells (DC-SIGN, CD209) has been demonstrated by electron microscopy to bind to glycans of the E protein and play a role in viral uptake. (42–44) Studies have shown that immature dendritic cells can be infected with DENV and the infection induced DC maturation. (45, 46) Studies using skin explants have demonstrated that DCs in the skin can be infected with locally inoculated DENV. (47, 48)

The increased risk for DHF during secondary infections suggests that preexisitng non-neutralizing cross-reactive antibodies may enhance viral uptake by host cells leading to more viral replication. A number of studies have shown higher viral load in patients with DHF compared to patients with DF. (49, 50) The levels of circulating NS1 protein were also found to be higher in patients with more severe disease. (51). DENV for the most part does not cause death of endothelial cells. However, soluble NS1 protein has been shown to activate complement and may cause plasma leakage. (10) The kinetics of viral load which peak at the time of presentation (febrile phase) and rapidly declines at the time of defervescence and plasma leakage suggests that direct effect of virus on vascular permeability is not likely. Rather, the increase in permeability likely occurs as a consequence of virus induced host responses. DENV infected cells have been shown to produce a number of proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8 and other chemokines. (9, 46, 52–54) Elevated levels of these mediators have been documented in DHF cases. (55, 56)

Studies comparing the magnitude of T cell response during and after DENV infections have demonstrated more intense activation in patients with DHF compared to patients with DF both in terms of activation markers and the magnitude of T cell expansion. (57–59) Studies have shown that CD8+ T cells specific to DENV serotype of a prior infection appear to be preferentially expanded during a secondary infection. (59) Analysis of the functional phenotypes of CD8+ T cells in DHF cases have revealed that cross recognition is associated with reduced cytolytic potential without much effect on cytokine production. (60, 61) Further, activation with peptide variants has been shown to induce different sets of cytokines when compared to stimulation with the proband peptide in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (62–64) Cytokines and chemokines induced by suboptimal activation of T cells may have effects on vascular permeability leading to plasma leakage in DHF.

A series of studies have suggested that DENV-induced autoantibodies play a role in the pathogenesis of DHF. A number of studies have reported that human and mouse antibodies to NS1 bind to host cells including endothelial cells and platelets. (65–69). Antibody binding to endothelial cells leads to apoptosis of these cells. (66) In contrast, binding to platelets leads to activation of platelets. (69) The target molecules of these antibodies have not been identified. Passive transfer of these antibodies into mice has induced various changes including bleeding and coagulopathy, elevated liver enzyme levels and endothelial cell death which appeared to be nitric oxide and caspase dependent. (65–67) Since DHF is self-limited and patients usually recover rapidly without any sign of autoimmune diseases, the role of these antibodies in the pathogenesis of DHF in humans remains unclear.

Thus, both host and viral factors are involved in determining the severity of dengue illness. Preexisitng antibodies and host genetic susceptibility (such as the polymorphism in DC-SIGN or Fc receptor) influence viral uptake and replication which in turn induces an intense activation of both the innate and the adaptive immune systems. In particular, an aberrant or suboptimal activation of cross-reactive dengue specific T cells may lead to poor viral clearance and the production of mediators with proinflammatory and vasoactive functions. Mediators released by T cells and by virus infected cells in combination with complement activation by viral proteins and immune complexes lead to an increase in vascular permeability (figure 2).

Figure 2. Immunopathogenesis of DHF.

Primary exposure to dengue virus induces both humoral (antibodies) and cellular (T cells) mediated immune responses. During a secondary infection with a different dengue virus serotype, cross-reactive, non-neutralizing antibodies bind to virus and enhance viral uptake via Fc receptors resulting in enhanced viral replication and higher antigen load which lead to an exaggerated activation of cross-reactive dengue specific T cells. Dengue virus may have direct effects on endothelial cell such as modulation of cell surface molecule and cytokine receptor expression. Biological mediators released by T cells and by virus infected cells along with complement activation by viral proteins and immune complexes, may result in enhanced vascular permeability and coagulopathy.

The role of endothelial cells in DHF

Although DENV can clearly infect human endothelial cell lines IN VITRO, conclusive evidence of DENV infection of endothelial cells IN VIVO is lacking. Dengue antigen but not genome was detected in endothelial cells in the liver sinusoids and the alveoli in human autopsy samples (39). A recent study has demonstrated the presence of NS3 protein in endothelial cells in the spleen but not in other organs. (40) Scarcities of human autopsy studies, the limited panels of tissues examined, and the time of specimen collection, which was usually after peak viremia in most studies, have made it difficult to conclusively determine the infection of endothelial cells by DENV. In several recent studies in mice, dengue antigen has been detected in endothelial cells in infected mice. (33, 70) In humans, swelling of endothelial cells but not extensive endothelial cell death or vasculitis has been reported. (38) Apoptosis of endothelial cells in the lungs and intestinal mucosa in fatal DHF cases has been demonstrated in one human autopsy study but the extent of apoptosis was not quantified and appeared to be rather limited. (41) Apoptosis of endothelial cells has been demonstrated in mice and has been proposed to be the mechanism of vascular leakage (65, 71).

Transcriptional activity, protein production and cell surface protein expression by endothelial cells are significantly altered by DENV. Several pathways which maybe involved in the pathogenesis of DHF are affected including inflammation, apoptosis and coagulation. (72) Several chemokines are produced by DENV infected endothelial cells IN VITRO such as MCP-1, RANTES and IL-8. (52, 56, 73) DENV also alters the production of coagulation factors by endothelial cells. Up-regulation of tissue plasminogen, thrombomodulin, PAR-1 receptor and tissue factor receptor, and down-regulation of tissue factor inhibitor and activated protein C have been reported. (74–77) Consistent with these findings, elevated levels of tissue factor and thrombomodulin have been found in DHF cases. (78)

Expression of cell surface molecules of endothelial cells is affected by DENV. Expression of ICAM-1 and beta-3-integrin on microvascular endothelial cell lines has been reported. (79–81) Interestingly, blocking of beta-3 integrin expression or blocking its functions by antibodies inhibits DENV entry and replication in microvascular endothelial cells, suggesting that DENV infection may enhance subsequent rounds of virus entry into endothelial cells by over expressing beta-3 integrin. Expression of cytokine receptors is also affected by DENV. Infection of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) results in a decrease in the soluble form of VEGF receptor2 (sVEGFR-2) in culture supernatants and a concomitant increase in membrane expression of VEGFR-2. (82) This effect is virus dose dependent. Plasma levels of sVEGFR-2 in DHF patients progressively decline during the course of the illness and inversely correlate with the plasma viral load, providing an IN VIVO correlate for the IN VITRO findings. This decline was associated with a simultaneous increase in plasma free VEGF. These findings suggest that DENV-induced changes in the expression of receptors for permeability enhancing mediators may be a mechanism involved in plasma leakage in DHF.

Interactions between the immune system and endothelial cells in DHF

Monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells are the major targets for DENV. Infection of these cells results in the production of mediators that may affect the functions of endothelial cells. Supernatant from DENV infected monocytes induces permeability changes in the HUVEC monolayer. This is due partly to TNF-α. (53) A study has demonstrated that infection with DENV up-regulates the expression of matrix metalloprotease enzymes, MMP-2 and MMP-9, by dendritic cells. (83) HUVEC monolayers treated with culture supernatants from infected dendritic cells exhibit enhanced permeability in association with a down regulation of surface platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) and VE-cadherin expression and F-actin reorganization. Injection of culture supernatants from DENV infected dendritic cells also caused localized plasma leakage and bleeding IN VIVO. DENV infection of endothelial cells has been reported to upregulate MMP-2 and increase permeability. (84) It has been postulated that increased MMPs by DENV infected cells may be a mechanism of vascular leakage in DHF. However, the general lack of structural changes of vessels in histology studies of human cases seems to argue against this hypothesis.

The interaction between endothelial cells, DENV and immune cells has been examined in a study in which HUVEC was infected with DENV and co-cultured with naïve PBMC. (85) Neither DENV infection nor PBMC alone had an effect on the permeability of the HUVEC monolayer. However, increased permeability was observed when HUVEC were infected with live DENV and PBMC were added. The effect of PBMC was mediated by adherent, CD14+ cells indicating that macrophages are the critical cells. The increase in permeability was associated with a down-regulation of vascular endothelial cadherin expression.

In summary, a complex interaction between DENV, immune cells and endothelial cells impacts endothelial cell barrier function. DENV may affect endothelial cells directly or indirectly through mediators released from infected or activated immune cells. Changes in the expression of adhesion molecules, enzymes, and cytokine receptors on endothelial cells may lead to enhanced vascular permeability and the activation of the coagulation system in DHF (figure 2).

Remaining questions and future research

Many questions remain unresolved regarding the mechanisms of plasma leakage in DHF. DHF shares many of the clinical manifestations and pathogenesis with other viral hemorrhagic fevers such as fever, thrombocytopenia, hemorrhagic tendency and plasma leakage. (86–88) Infection of the endothelium has been better documented and plays a more prominent role in the pathogenesis of other hemorrhagic fevers such as Hantaviruses and, to a lesser extent, Ebola virus infection. Tissue destruction in Ebolavirus infection is attributed to direct viral effects since there is little tissue inflammation. (88) Both tissue inflammation and tissue destruction in DHF are rather limited. Although several mediators with proinflammatory effects are reported to be elevated in DHF, these levels are elevated only relative to levels found in DF or normal controls. Therefore, the true contribution of these molecules in the pathogenesis of DHF is not known. The overall lack of tissue inflammation, the transient nature of plasma leakage and the rapid recovery in DHF patients suggest that mediators that regulate permeability with relatively little pro-inflammatory effects may play an important role in plasma leakage in DHF. These cytokines include those involved in vessel development such as VEGF and angiopoietins. Alternatively, the lack of inflammation in DHF may be due to mediators with anti-inflammatory or anti-chemotactic effects. Elevated levels of TGF-beta have been reported in DHF patients. (89, 90) Whether DENV elicits other biological mediators with anti-inflammatory properties remains to be determined.

The predisposition for DHF during secondary infections implicates the adaptive immune system in the pathogenesis of DHF. This is in contrast to Ebolavirus infection in which innate immunity appears to play a major role. (87) Adaptive immunity, particularly CD8+ T cells has been demonstrated to be important in the pathogenesis of Hantavirus. (91, 92) The adaptive immune arms that are involved in plasma leakage in DHF are not defined. However, the association between certain HLA alleles and disease severity suggests that T cells may be important in this process. Given the importance of DENV as a global and emerging public health problem, there are currently considerable efforts in developing vaccines against DENV. Therefore, it is imperative that the immune effectors that confer either protection or pathology be identified.. Dissecting the effector functions related to protection or pathology will require animal models that can reproduce the clinical features of DHF. The precise delineation of the roles of various mediators in plasma leakage can only be done with genetically modified animals or by functional ablation of such mediators in animal models. Despite the recent progress in the development of animal models, studies in humans remain indispensable in the effort to gain further insights into this condition. Well designed, prospective studies of well characterized dengue cases are still instrumental in our understanding of this disease. Insights in vascular biology and the interplay between virus, the immune system and endothelium in DHF will be crucial for the development of predictive markers and therapeutic interventions for this condition.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. In-Kyu Yoon for reading the manuscript, doctors and nurses of Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health and the staff of the Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences for patient care and sample collection.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NIH-P01AI34533. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private ones of the authors and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the view of the U.S. Government.

References

- 1.Organization WH. [accessed 1 December 2008];Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. http://wwwwhoint/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/

- 2.Organization WH, editor. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. WHO; Geneva: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinheiro FP, Corber SJ. Global situation of dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever, and its emergence in the Americas. World Health Stat Q. 1997;50(3–4):161–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kouri G, Guzman MG, Valdes L, et al. Reemergence of dengue in Cuba: a 1997 epidemic in Santiago de Cuba. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998 Jan-Mar;4(1):89–92. doi: 10.3201/eid0401.980111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gubler D, Kuno G, Markoff L. Flavivirus, Field’s Virology. 5. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindenbach BD, Thiel H-J, Rice CM. Flaviviridae: The Viruses and Their Replication, Field’s Virology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones M, Davidson A, Hibbert L, et al. Dengue virus inhibits alpha interferon signaling by reducing STAT2 expression. Journal of virology. 2005 May;79(9):5414–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5414-5420.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munoz-Jordan JL, Laurent-Rolle M, Ashour J, et al. Inhibition of alpha/beta interferon signaling by the NS4B protein of flaviviruses. Journal of virology. 2005 Jul;79(13):8004–13. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8004-8013.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medin CL, Fitzgerald KA, Rothman AL. Dengue virus nonstructural protein NS5 induces interleukin-8 transcription and secretion. Journal of virology. 2005 Sep;79(17):11053–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11053-11061.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avirutnan P, Punyadee N, Noisakran S, et al. Vascular leakage in severe dengue virus infections: a potential role for the nonstructural viral protein NS1 and complement. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2006 Apr 15;193(8):1078–88. doi: 10.1086/500949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Organization WH. Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever: diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. 2. WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pancharoen C, Rungsarannont A, Thisyakorn U. Hepatic dysfunction in dengue patients with various severity. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002 Jun;85( Suppl 1):S298–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cam BV, Fonsmark L, Hue NB, et al. Prospective case-control study of encephalopathy in children with dengue hemorrhagic fever. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2001 Dec;65(6):848–51. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen HL, Bienfait HP, Jansen CL, et al. Fatal cerebral oedema associated with primary dengue infection. J Infect. 1998 May;36(3):344–6. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(98)94783-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srikiatkhachorn A, Krautrachue A, Ratanaprakarn W, et al. Natural history of plasma leakage in dengue hemorrhagic fever: a serial ultrasonographic study. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2007 Apr;26(4):283–90. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000258612.26743.10. discussion 91–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balasubramanian S, Janakiraman L, Kumar SS, et al. A reappraisal of the criteria to diagnose plasma leakage in dengue hemorrhagic fever. Indian pediatrics. 2006 Apr;43(4):334–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishnamurti C, Kalayanarooj S, Cutting MA, et al. Mechanisms of hemorrhage in dengue without circulatory collapse. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2001 Dec;65(6):840–7. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nimmannitya S. Clinical manifestations of Dengue/Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever. In: Thongcharoen P, editor. Monograph on Dengue/Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever. World Health Organization; New Delhi: 1993. pp. 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wills BA, Nguyen MD, Ha TL, et al. Comparison of three fluid solutions for resuscitation in dengue shock syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Sep 1;353(9):877–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke DS, Nisalak A, Johnson DE, et al. A prospective study of dengue infections in Bangkok. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 1988 Jan;38(1):172–80. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endy TP, Chunsuttiwat S, Nisalak A, et al. Epidemiology of inapparent and symptomatic acute dengue virus infection: a prospective study of primary school children in Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand. Am J Epidemiol. 2002 Jul 1;156(1):40–51. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halstead SB, O’Rourke EJ. Antibody-enhanced dengue virus infection in primate leukocytes. Nature. 1977 Feb 24;265(5596):739–41. doi: 10.1038/265739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halstead SB. In vivo enhancement of dengue virus infection in rhesus monkeys by passively transferred antibody. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1979 Oct;140(4):527–33. doi: 10.1093/infdis/140.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stephens HA, Klaythong R, Sirikong M, et al. HLA-A and -B allele associations with secondary dengue virus infections correlate with disease severity and the infecting viral serotype in ethnic Thais. Tissue Antigens. 2002 Oct;60(4):309–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.600405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soundravally R, Hoti SL. Polymorphisms of the TAP 1 and 2 gene may influence clinical outcome of primary dengue viral infection. Scand J Immunol. 2008 Jun;67(6):618–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakuntabhai A, Turbpaiboon C, Casademont I, et al. A variant in the CD209 promoter is associated with severity of dengue disease. Nat Genet. 2005 May;37(5):507–13. doi: 10.1038/ng1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandez-Mestre MT, Gendzekhadze K, Rivas-Vetencourt P, et al. TNF-alpha-308A allele, a possible severity risk factor of hemorrhagic manifestation in dengue fever patients. Tissue Antigens. 2004 Oct;64(4):469–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rico-Hesse R, Harrison LM, Salas RA, et al. Origins of dengue type 2 viruses associated with increased pathogenicity in the Americas. Virology. 1997 Apr 14;230(2):244–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kochel TJ, Watts DM, Halstead SB, et al. Effect of dengue-1 antibodies on American dengue-2 viral infection and dengue haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 2002 Jul 27;360(9329):310–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09522-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodrigo WW, Alcena DC, Kou Z, et al. Difference between the abilities of human Fcgamma receptor-expressing CV-1 cells to neutralize American and Asian genotypes of dengue virus 2. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009 Feb;16(2):285–7. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00363-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holden KL, Harris E. Enhancement of dengue virus translation: role of the 3′ untranslated region and the terminal 3′ stem-loop domain. Virology. 2004 Nov 10;329(1):119–33. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leitmeyer KC, Vaughn DW, Watts DM, et al. Dengue virus structural differences that correlate with pathogenesis. Journal of virology. 1999 Jun;73(6):4738–47. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4738-4747.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barth OM, Barreto DF, Paes MV, et al. Morphological studies in a model for dengue-2 virus infection in mice. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006 Dec;101(8):905–15. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000800014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kyle JL, Beatty PR, Harris E. Dengue virus infects macrophages and dendritic cells in a mouse model of infection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2007 Jun 15;195(12):1808–17. doi: 10.1086/518007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shresta S, Sharar KL, Prigozhin DM, et al. Murine model for dengue virus-induced lethal disease with increased vascular permeability. Journal of virology. 2006 Oct;80(20):10208–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00062-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mota J, Rico-Hesse R. Humanized mice show clinical signs of dengue fever according to infecting virus genotype. Journal of virology. 2009 Sep;83(17):8638–45. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00581-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bente DA, Melkus MW, Garcia JV, et al. Dengue fever in humanized NOD/SCID mice. Journal of virology. 2005 Nov;79(21):13797–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13797-13799.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhamarapravati N, Tuchinda P, Boonyapaknavik V. Pathology of Thailand haemorrhagic fever: a study of 100 autopsy cases. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1967 Dec;61(4):500–10. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1967.11686519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jessie K, Fong MY, Devi S, et al. Localization of dengue virus in naturally infected human tissues, by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2004 Apr 15;189(8):1411–8. doi: 10.1086/383043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balsitis SJ, Coloma J, Castro G, et al. Tropism of dengue virus in mice and humans defined by viral nonstructural protein 3-specific immunostaining. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2009 Mar;80(3):416–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Limonta D, Capo V, Torres G, et al. Apoptosis in tissues from fatal dengue shock syndrome. J Clin Virol. 2007 Sep;40(1):50–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marovich M, Grouard-Vogel G, Louder M, et al. Human dendritic cells as targets of dengue virus infection. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2001 Dec;6(3):219–24. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tassaneetrithep B, Burgess TH, Granelli-Piperno A, et al. DC-SIGN (CD209) mediates dengue virus infection of human dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2003 Apr 7;197(7):823–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pokidysheva E, Zhang Y, Battisti AJ, et al. Cryo-EM reconstruction of dengue virus in complex with the carbohydrate recognition domain of DC-SIGN. Cell. 2006 Feb 10;124(3):485–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Libraty DH, Pichyangkul S, Ajariyakhajorn C, et al. Human dendritic cells are activated by dengue virus infection: enhancement by gamma interferon and implications for disease pathogenesis. Journal of virology. 2001 Apr;75(8):3501–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3501-3508.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho LJ, Wang JJ, Shaio MF, et al. Infection of human dendritic cells by dengue virus causes cell maturation and cytokine production. J Immunol. 2001 Feb 1;166(3):1499–506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taweechaisupapong S, Sriurairatana S, Angsubhakorn S, et al. In vivo and in vitro studies on the morphological change in the monkey epidermal Langerhans cells following exposure to dengue 2 (16681) virus. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1996 Dec;27(4):664–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu SJ, Grouard-Vogel G, Sun W, et al. Human skin Langerhans cells are targets of dengue virus infection. Nat Med. 2000 Jul;6(7):816–20. doi: 10.1038/77553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Libraty DH, Endy TP, Houng HS, et al. Differing influences of virus burden and immune activation on disease severity in secondary dengue-3 virus infections. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2002 May 1;185(9):1213–21. doi: 10.1086/340365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaughn DW, Green S, Kalayanarooj S, et al. Dengue viremia titer, antibody response pattern, and virus serotype correlate with disease severity. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2000 Jan;181(1):2–9. doi: 10.1086/315215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Libraty DH, Young PR, Pickering D, et al. High circulating levels of the dengue virus nonstructural protein NS1 early in dengue illness correlate with the development of dengue hemorrhagic fever. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2002 Oct 15;186(8):1165–8. doi: 10.1086/343813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bosch I, Xhaja K, Estevez L, et al. Increased production of interleukin-8 in primary human monocytes and in human epithelial and endothelial cell lines after dengue virus challenge. Journal of virology. 2002 Jun;76(11):5588–97. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5588-5597.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carr JM, Hocking H, Bunting K, et al. Supernatants from dengue virus type-2 infected macrophages induce permeability changes in endothelial cell monolayers. J Med Virol. 2003 Apr;69(4):521–8. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee YR, Liu MT, Lei HY, et al. MCP-1, a highly expressed chemokine in dengue haemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome patients, may cause permeability change, possibly through reduced tight junctions of vascular endothelium cells. J Gen Virol. 2006 Dec;87(Pt 12):3623–30. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cardier JE, Marino E, Romano E, et al. Proinflammatory factors present in sera from patients with acute dengue infection induce activation and apoptosis of human microvascular endothelial cells: possible role of TNF-alpha in endothelial cell damage in dengue. Cytokine. 2005 Jun 21;30(6):359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Avirutnan P, Malasit P, Seliger B, et al. Dengue virus infection of human endothelial cells leads to chemokine production, complement activation, and apoptosis. J Immunol. 1998 Dec 1;161(11):6338–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Green S, Pichyangkul S, Vaughn DW, et al. Early CD69 expression on peripheral blood lymphocytes from children with dengue hemorrhagic fever. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1999 Nov;180(5):1429–35. doi: 10.1086/315072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mathew A, Kurane I, Green S, et al. Predominance of HLA-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses to serotype-cross-reactive epitopes on nonstructural proteins following natural secondary dengue virus infection. Journal of virology. 1998 May;72(5):3999–4004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3999-4004.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mongkolsapaya J, Dejnirattisai W, Xu XN, et al. Original antigenic sin and apoptosis in the pathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Nat Med. 2003 Jul;9(7):921–7. doi: 10.1038/nm887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mongkolsapaya J, Duangchinda T, Dejnirattisai W, et al. T cell responses in dengue hemorrhagic fever: are cross-reactive T cells suboptimal? J Immunol. 2006 Mar 15;176(6):3821–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dong T, Moran E, Vinh Chau N, et al. High Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Secretion and Loss of High Avidity Cross-Reactive Cytotoxic T-Cells during the Course of Secondary Dengue Virus Infection. PloS one. 2007;2(12):e1192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beaumier CM, Mathew A, Bashyam HS, et al. Cross-reactive memory CD8(+) T cells alter the immune response to heterologous secondary dengue virus infections in mice in a sequence-specific manner. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2008 Feb 15;197(4):608–17. doi: 10.1086/526790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bashyam HS, Green S, Rothman AL. Dengue virus-reactive CD8+ T cells display quantitative and qualitative differences in their response to variant epitopes of heterologous viral serotypes. J Immunol. 2006 Mar 1;176(5):2817–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mangada MM, Rothman AL. Altered cytokine responses of dengue-specific CD4+ T cells to heterologous serotypes. J Immunol. 2005 Aug 15;175(4):2676–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin CF, Lei HY, Shiau AL, et al. Antibodies from dengue patient sera cross-react with endothelial cells and induce damage. J Med Virol. 2003 Jan;69(1):82–90. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin CF, Lei HY, Shiau AL, et al. Endothelial cell apoptosis induced by antibodies against dengue virus nonstructural protein 1 via production of nitric oxide. J Immunol. 2002 Jul 15;169(2):657–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin CF, Wan SW, Chen MC, et al. Liver injury caused by antibodies against dengue virus nonstructural protein 1 in a murine model. Lab Invest. 2008 Oct;88(10):1079–89. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Falconar AK. The dengue virus nonstructural-1 protein (NS1) generates antibodies to common epitopes on human blood clotting, integrin/adhesin proteins and binds to human endothelial cells: potential implications in haemorrhagic fever pathogenesis. Arch Virol. 1997;142(5):897–916. doi: 10.1007/s007050050127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sun DS, King CC, Huang HS, et al. Antiplatelet autoantibodies elicited by dengue virus non-structural protein 1 cause thrombocytopenia and mortality in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2007 Nov;5(11):2291–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yen YT, Chen HC, Lin YD, et al. Enhancement by tumor necrosis factor alpha of dengue virus-induced endothelial cell production of reactive nitrogen and oxygen species is key to hemorrhage development. Journal of virology. 2008 Dec;82(24):12312–24. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00968-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen HC, Hofman FM, Kung JT, et al. Both virus and tumor necrosis factor alpha are critical for endothelium damage in a mouse model of dengue virus-induced hemorrhage. Journal of virology. 2007 Jun;81(11):5518–26. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02575-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Warke RV, Xhaja K, Martin KJ, et al. Dengue virus induces novel changes in gene expression of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Journal of virology. 2003 Nov;77(21):11822–32. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11822-11832.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang YH, Lei HY, Liu HS, et al. Dengue virus infects human endothelial cells and induces IL-6 and IL-8 production. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2000 Jul-Aug;63(1–2):71–5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.63.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jiang Z, Tang X, Xiao R, et al. Dengue virus regulates the expression of hemostasis-related molecules in human vein endothelial cells. J Infect. 2007 Aug;55(2):e23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.04.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huang YH, Lei HY, Liu HS, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator induced by dengue virus infection of human endothelial cells. J Med Virol. 2003 Aug;70(4):610–6. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huerta-Zepeda A, Cabello-Gutierrez C, Cime-Castillo J, et al. Crosstalk between coagulation and inflammation during Dengue virus infection. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2008 May;99(5):936–43. doi: 10.1160/TH07-08-0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cabello-Gutierrez C, Manjarrez-Zavala ME, Huerta-Zepeda A, et al. Modification of the cytoprotective protein C pathway during Dengue virus infection of human endothelial vascular cells. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2009 May;101(5):916–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Butthep P, Chunhakan S, Tangnararatchakit K, et al. Elevated soluble thrombomodulin in the febrile stage related to patients at risk for dengue shock syndrome. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2006 Oct;25(10):894–7. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000237918.85330.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anderson R, Wang S, Osiowy C, et al. Activation of endothelial cells via antibody-enhanced dengue virus infection of peripheral blood monocytes. Journal of virology. 1997 Jun;71(6):4226–32. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4226-4232.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peyrefitte CN, Pastorino B, Grau GE, et al. Dengue virus infection of human microvascular endothelial cells from different vascular beds promotes both common and specific functional changes. J Med Virol. 2006 Feb;78(2):229–42. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang JL, Wang JL, Gao N, et al. Up-regulated expression of beta3 integrin induced by dengue virus serotype 2 infection associated with virus entry into human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007 May 11;356(3):763–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Srikiatkhachorn A, Ajariyakhajorn C, Endy TP, et al. Virus-induced decline in soluble vascular endothelial growth receptor 2 is associated with plasma leakage in dengue hemorrhagic Fever. Journal of virology. 2007 Feb;81(4):1592–600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01642-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Luplertlop N, Misse D, Bray D, et al. Dengue-virus-infected dendritic cells trigger vascular leakage through metalloproteinase overproduction. EMBO Rep. 2006 Nov;7(11):1176–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Luplertlop N, Misse D. MMP cellular responses to dengue virus infection-induced vascular leakage. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2008 Jul;61(4):298–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dewi BE, Takasaki T, Kurane I. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells increase the permeability of dengue virus-infected endothelial cells in association with downregulation of vascular endothelial cadherin. J Gen Virol. 2008 Mar;89(Pt 3):642–52. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schnittler HJ, Feldmann H. Viral hemorrhagic fever--a vascular disease? Thrombosis and haemostasis. 2003 Jun;89(6):967–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zampieri CA, Sullivan NJ, Nabel GJ. Immunopathology of highly virulent pathogens: insights from Ebola virus. Nature immunology. 2007 Nov;8(11):1159–64. doi: 10.1038/ni1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zaki SR, Greer PW, Coffield LM, et al. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Pathogenesis of an emerging infectious disease. The American journal of pathology. 1995 Mar;146(3):552–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Agarwal R, Elbishbishi EA, Chaturvedi UC, et al. Profile of transforming growth factor-beta 1 in patients with dengue haemorrhagic fever. International journal of experimental pathology. 1999 Jun;80(3):143–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.1999.00107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Laur F, Murgue B, Deparis X, et al. Plasma levels of tumour necrosis factor alpha and transforming growth factor beta-1 in children with dengue 2 virus infection in French Polynesia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1998 Nov-Dec;92(6):654–6. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)90800-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sironen T, Klingstrom J, Vaheri A, et al. Pathology of Puumala hantavirus infection in macaques. PloS one. 2008;3(8):e3035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kilpatrick ED, Terajima M, Koster FT, et al. Role of specific CD8+ T cells in the severity of a fulminant zoonotic viral hemorrhagic fever, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. J Immunol. 2004 Mar 1;172(5):3297–304. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]