Abstract

Background

Breastfeeding may protect against infections, but its optimal duration remains controversial. We aimed to study the association of the duration of full and any breastfeeding with infections the first 18 months of life.

Methods

The Norwegian Mother and Child study (MoBa) is a prospective birth cohort which recruited expecting mothers giving birth from 2000–2009. We analyzed data from the full cohort (n=70 511) and sibling sets (n=21 220) with parental report of breastfeeding and infections. The main outcome measures were the relative risks for hospitalisation for infections from 0–18 months by age at introduction of complementary foods and duration of any breastfeeding.

Results

While we found some evidence for an overall association between longer duration of full breastfeeding and lower risk of hospitalisations for infections, 7.3% of breastfed children who received complementary foods at 4–6 months of age compared to 7.7% of those receiving complementary foods after 6 months were hospitalised (adjusted relative risk [RR] 0.95, 95% CI 0.88–1.03). Higher risk of hospitalisation was observed in those breastfed six months or less (10.0%) compared to ≥12 months (7.6%, adjusted RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.14–1.31), but with similar risks for 6–11 months versus ≥12 months. Matched sibling analyses, minimising the confounding from shared maternal factors, showed non-significant associations and were generally weaker compared with the cohort analyses.

Conclusions

Our results support the recommendation to fully breastfeed for 4 months and to continue breastfeeding beyond 6 months, and suggest that protection against infections is limited to the first 12 months.

Keywords: Human milk, weaning, infectious disease, infancy

INTRODUCTION

There is an ongoing controversy regarding optimal breastfeeding duration and time of weaning.(1) The recommendation from the World Health Organization(2) to continue full breastfeeding until 6 months of age has been adopted by several industrialized countries.(1, 3–5) Still, only 1–13% of mothers in the UK, the US and Norway comply with this recommendation.(4, 6, 7) The WHO furthermore recommends to continue partial breastfeeding up to 2 year or beyond.(3) There is a need for more studies providing stronger evidence to underpin a revision of current guidelines, as stated by the WHO expert consultation.(8)

Protection against infections is one of several causes considered in the breastfeeding recommendations.(9, 10) These benefits appear particularly in developing countries with a high burden of infectious diseases in infancy, (11–13) where the risk of unsafe formula feeding adds to a higher pressure of infections.(8) These observations have partly been reproduced in industrialized countries.(6, 14)

Breastfeeding in wealthy societies is associated with health conscious behaviour,(15) and consequently, confounding effects of other healthy choices needs to be thoroughly investigated. Furthermore, previous studies have included few infants fully breastfed for 6 months. Underlying characteristics of this group could possibly confound the results, in addition to uncertainty in the estimates due to limited sample sizes.(6, 14, 16, 17) Moreover, few studies have addressed the optimal duration of breastfeeding beyond 6 months regarding infection prevention.(6, 14)

The main objective of this study was to assess whether the risk of hospitalisation for infections before age 18 months was different in infants introduced to complementary foods from 4–6 months compared to the recommended 6 months. Secondary objectives were to study whether duration of any breastfeeding was associated with hospitalisation and with infections in general. In addition to a traditional cohort analysis, we assessed whether breastfeeding predicted risk of infections in a matched sibling design.

METHODS

Cohort formation

The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) is a population-based pregnancy cohort study conducted by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.(18) Participants were recruited from all over Norway (rural/urban) from 1999–2008, and 95,200 mothers (40.6% of eligible) participated with one or more pregnancies. Written informed consent was obtained. The MoBa study was approved by The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics in South-Eastern Norway. The current study is based on version VII of the quality-assured data files released for research in June 2012.

Follow-up is conducted by mailed questionnaires. We use information from the baseline questionnaire completed around week 17 of pregnancy and two follow-up questionnaires at infant age 6 and 18 months (available at www.fhi.no/moba).

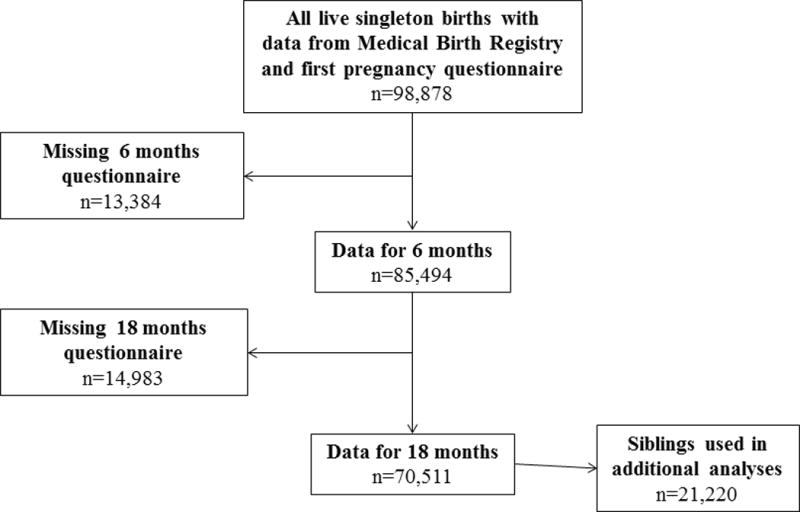

Only singletons whose parents returned questionnaires at 6 and 18 months of age (n=70,511, flow chart Figure 1) were included (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1 for characteristics of included and non-included participants). Children with missing data for any of the study variables were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1. Subjects included in the analyses. Siblings were part of the full cohort and also included in sibling analyses.

Abbreviation: MBR, Medical Birth Registry.

a 225 of the 13 384 were lost due to deaths in the observation period.

b 21 of the 14 983 were lost due to deaths in the observation period.

In order to reduce bias that may occur due to differences in self-reporting of infections and confounding maternal effects, siblings in the cohort were studied in a secondary analysis.

Main exposure: Infant feeding

In the 6 months’ questionnaire, ongoing breastfeeding or formula feeding from the first week in monthly intervals and age at introduction of solids was specified up until completion (median 27 weeks). From 6 to 18 months of age, the mothers reported whether they were breastfeeding in four intervals (6–8, 9–11, 12–14 and 15–18 months). The median value of each interval was used as a fixed value in calculations of breastfeeding duration. For the regression analyses, duration of any breastfeeding was categorized into 6 intervals (no breastfeeding, 0.1–3, 4–6, 6.1–8, 9–11 and ≥12 months). Full breastfeeding was defined as breastfeeding from birth without any formula or solids. This allows for water and vitamins, different from the strict definition of exclusive breastfeeding.

To assess whether partial breastfeeding was associated with different risk of infections than full breastfeeding, age at introduction of complementary foods (formula or solid foods) in infants breastfed >6 months was analysed in categories <1, 1–3 and 4–5 months age with full breastfeeding for 6 months as the reference category. We performed sub-analyses for the age at introduction of formula or solids, all adjusted for the duration of any breastfeeding.

Main outcome definitions: Infections

The primary outcome was hospitalisation due to infection by maternal report from 0–18 months. In additional analyses hospitalisation was separated in age 0–6 and 6–18 months. We assessed the validity of this outcome from the questionnaires by comparing it to hospital statistics in a subsample from one major hospital, where 197 of 212 admissions were correctly reported in questionnaires (sensitivity 93%).

Secondary outcomes were infections regardless of hospitalisation from 0–18 months indicated from a specified list. Lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI=pneumonia/bronchiolitis), gastroenteritis (GE) and acute otitis media were dichotomized (none vs any). Upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) and frequent infections (total number of the four types of infections) were dichotomized corresponding to the upper quintile of the distribution in the whole sample (URTI >8 or “frequent infections” >10, respectively).

Other covariates

Information regarding maternal age, birth weight, gestational age, parity, mode of delivery and gender was obtained from the Medical Birth Registry. The first questionnaire provided information on smoking during pregnancy, paternal smoking and duration of maternal education in four categories. Duration of child day-care outside home was categorized in four groups (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1 for covariates and categorization).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using the SPSS 20.0 statistical software package (IBM SPSS inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP Texas, USA). The main analysis was conducted using binary regression models to obtain relative risks (RR), with robust variance to correct for potential clustering within families. Confounders reported from previous studies were preselected. Other covariates associated with any of the outcomes with 95% confidence intervals for RR not including 1.00 in unadjusted analyses were assessed for inclusion in the multiple regression models, but removed from the final model if the estimates changed <10%. As sensitivity analyses to assess robustness of findings, we explored the potential impact of using different cut-offs for the total number of URTI and total infections, and fitted Poisson regression models for number of infectious episodes. Sensitivity analyses were consistent with our main analyses (data not shown).

Finally, we estimated the odds ratio for infections in siblings (matched sets conditioned on the maternal origin), using conditional logistic regression models. In this model, covariates that are identical within sibling sets will not contribute to the final estimates. Thus, only sibling sets with different duration of breastfeeding can potentially change the odds ratio from 1. We included as covariates potential confounders that could differ among siblings (detailed in Table 1), comparing an unmatched design to the sibling analysis.

Table 1a.

Duration of full breastfeeding and infections in the first 18 months of life in a sibling and full cohort analysis.

| Endpoint | Model | Number of children with endpoint (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) per month before introduction of complementary foods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalisation for any infection | Siblings matched (n=12,495) | 1,012 (8.1) | 0.975 (0.924–1.029) |

| Full cohort (n=56,993) | 4,315 (7.6) | 0.978 (0.963–0.994) | |

| Any lower respiratory tract infection | Siblings matched (n=12,147) | 1,674 (13.8) | 0.994 (0.952–1.038) |

| Full cohort (n=55,301) | 7,124 (12.9) | 0.990 (0.978–1.003) | |

| Any gastro-enteritis | Siblings matched (n=11,739) | 7,008 (59.7) | 0.981 (0.950–1.013) |

| Full cohort (n=53,226) | 31,651 (59.5) | 0.974 (0.965–0.983) | |

| Upper respiratory tract infections (≥9) | Siblings matched (n=11,988) | 2,581 (21.5) | 0.982 (0.943–1.022) |

| Full cohort (n=54,437) | 11,236 (20.6) | 0.968 (0.957–0.978) | |

| Frequent infections (≥11) | Siblings matched (n=11,988) | 2,312 (19.3) | 0.973 (0.933–1.015) |

| Full cohort (n=54,437) | 10,190 (18.7) | 0.959 (0.949–0.970) |

RESULTS

The mean duration of any breastfeeding was 10.0 months (SD 4.5), 80.8% were breastfed >6 months. Fourteen per cent were fully breastfed for 6 months; 0.9% was never breastfed. Longer duration of any breastfeeding was strongly associated with higher maternal age and parity, education, non-smoking status, vaginal delivery and day-care at home (all p<0.001, see Table, Supplemental Digital Contents 2).

Before the age of 18 months, 8.0% were admitted to hospital for infections. Gastroenteritis or LRTI accounted for 68% (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Contents 3, which demonstrates that the age at admission was evenly distributed during the period from 0–18 months). The frequency of all infections increased gradually with age (see Table, Supplemental Digital Contents 4).

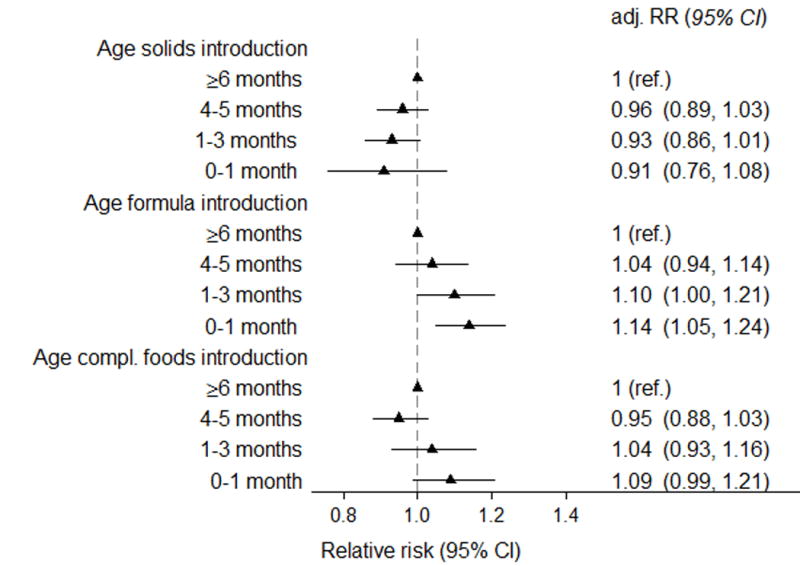

Age at introduction of complementary foods and infections

Age at introduction of complementary foods was a significant predictor for hospitalisation for infections among infants who were breastfed for a minimum of 6 months (adjusted relative risk [RR] 0.98 per month delay, 95% CI 0.97–1.00, p for trend 0.01). This association was driven by a higher risk for hospitalisation in those with introduction of complementary foods <4 months age (Figure 2). In categorical analyses, hospitalisation for infections was reported in 7.7% of infants fully breastfed for 6 months compared to 7.3% of those introduced to complementary foods at 4–6 months (aRR 0.95, 0.88–1.03, Figure 2, for further details see Table, Supplemental Digital Contents 5).

Figure 2. Relative risk of hospital admission for infections the first 18 months of life by age at introduction of complementary foods, solid foods and formula in infants breastfed > 6 months age (n=57 007).).

Relative risks were adjusted for maternal age and parity (three categories), caesarean section, maternal smoking, education, birthweight (< 2500 g, 2500–3499, 3500–4499, >4500 g), gestational age (</> 37 weeks), gender, day-care outside home and duration of any breastfeeding. Adj.RR=adjusted relative risk, CI=Confidence interval

The risk was significantly lower when formula introduction was delayed (aRR 0.96 per month, 0.93–0.98), but formula introduction from 4 months was not associated with increased risk of hospitalisation. For solids introduction, we found a non-significant trend in the opposite direction (aRR 1.03 per month, 1.00–1.07), Figure 2.

We also performed sub-analyses separating the main outcome in time periods of 0–6 months and 6–18 months. The point estimates did not change substantially, but the confidence intervals became wider due to the lower proportion with events. (Table, Supplemental Digital Contents 5).

When we analysed all infections regardless of hospitalisation, introduction of complementary foods <4 months was associated with an increased risk for gastroenteritis, URTI and frequent infections but not for LRTI (details in Table, Supplemental Digital Contents 5).

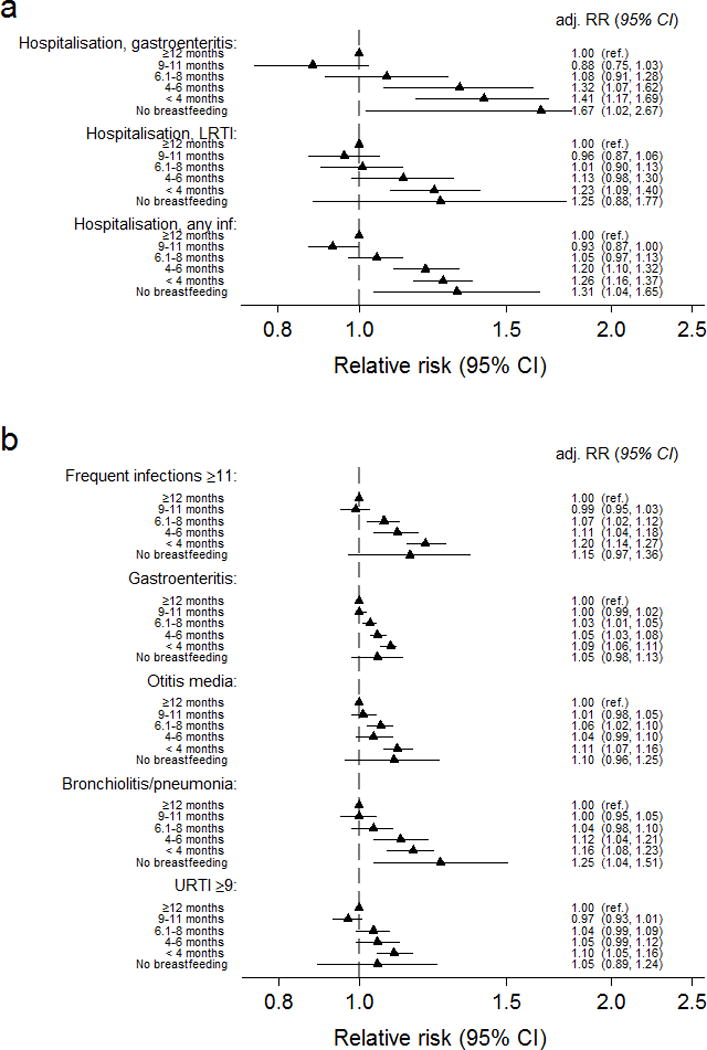

Duration of any breastfeeding and infections

Compared with infants breastfed ≥12 months, infants breastfed for <6 months had an increased risk for hospitalisation. The association was primarily driven by gastroenteritis (Figure 3a). Breastfeeding <6 months was in general associated with an increased risk for infectious outcomes regardless of hospitalisation (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. Relative risk of a) hospital admission for infection and b) any infection from 0–18 months by duration of any breastfeeding (n=70 511).

Relative risks were adjusted for maternal age and parity (three categories), caesarean section, maternal smoking, education, birthweight (< 2500 g, 2500–3499g, 3500–4500g, >4500 g), gestational age (</> 37 weeks), gender and day-care outside home. Adj.RR=adjusted relative risk, CI=Confidence interval, LRTI=Lower respiratory tract infection.

Infants breastfed for 6–11 months did not differ significantly from those breastfed ≥12 months regarding hospitalisation (Figure 3a), but with a slightly reduced risk of gastroenteritis, otitis media and frequent infections if breastfed up to 9 months (Figure 3b and Table, Supplemental Digital Contents 6)

Sibling analyses

The median difference in duration of full and any breastfeeding within sibling sets discordant for duration of breastfeeding was 1.5 and 3.0 months, respectively, and 41% had identical duration of any breastfeeding. The first-born sibling had a mean shorter duration of both full and any breastfeeding of 0.4 months. Infants with a matched sibling control with difference in duration of full breastfeeding (n=12,495) or any breastfeeding (n=11,149) contributed in the sibling analysis.

In the conditional logistic regression analysis of siblings we found no significant associations for age for introduction of complementary foods with hospital admission for infections, and with risk for infections regardless of hospitalisation (Table 1a). Similarly, duration of any breastfeeding was not a significant predictor (Table 1b). The odds ratios per month were generally closer to 1 in the conditional analysis compared to the unconditional full cohort analysis (Table 1).

Table 1b.

Duration of any breastfeeding and infections in the first 18 months of life in a sibling and full cohort analysis.

| Endpoint | Model | Number of children with endpoint (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) per month before introduction of complementary foods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalisation for any infection | Siblings matched (n=13,420) | 1,107 (8.3) | 0.994 (0.965–1.024) |

| Full cohort (n=70,487) | 5,669 (8.0) | 0.985 (0.979–0.992) | |

| Any lower respiratory tract infection | Siblings matched (n=13,043) | 1,854 (14.2) | 0.999 (0.973–1.026) |

| Full cohort (n=68,322) | 9,030 (13.2) | 0.990 (0.985–0.995) | |

| Any gastro-enteritis | Siblings matched (n=12,582) | 7,542 (59.9) | 0.994 (0.975–1.013) |

| Full cohort (n=65,852) | 39,393 (59.8) | 0.990 (0.986–0.994) | |

| Upper respiratory tract infections (≥9) | Siblings matched (n=12,857) | 2,806 (21.8) | 0.983 (0.960–1.007) |

| Full cohort (n=67,249) | 13,862 (20.6) | 0.996 (0.992–1.001) | |

| Frequent infections (≥11) | Siblings matched (n=12,857) | 2,542 (19.8) | 0.980 (0.955–1.005) |

| Full cohort (n=67,249) | 12,787 (19.0) | 0.990 (0.985–0.994) |

For each outcome, two models were run: a conditional logistic regression within sibling sets, and an unconditional logistic regression analysis in the full cohort with robust variance to correct for potential clustering within families. All models were adjusted for parity, gestational age (<37/≥ 37weeks), gender, caesarean section, birth weight category, day-care outside home, maternal age, maternal education and maternal smoking.

Only sibships discordant for endpoint contributed to this analysis, i.e. sibships where one child had the endpoint and at least one sibling did not.

Significant predictors for infections in the sibling model were birth order, birth weight <2500g, male gender and day-care outside home (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this large birth cohort, we found a small but significant trend for lower risk for hospitalisations for infections for each month of delaying complementary foods in breastfed infants. However, breastfed children who received complementary foods at 4–6 months of age had a similar risk as those delaying complementary foods to after 6 months, suggesting a threshold effect for duration of full breastfeeding. Breastfeeding for ≤6 months compared to ≥12 months was associated with an increased risk, whereas infants breastfed for 6–11 months had risks of hospitalisation similar to those breastfed ≥12 months. The estimated associations were weaker and non-significant in the sibling analysis compared with the full cohort analysis. The present study is the first in this field to include a discordant sibling analysis, an analysis that studies differences within sibling sets and thereby reduces the potential confounding from shared maternal factors.

The similar hospitalisation risk for infants introduced to complementary foods from 4–6 compared to ≥6 months parallels two previous cohort studies (6, 17) and the recent randomised controlled EAT trial.(19) In contrast, others have found a reduced risk of lower respiratory tract infections with 6 months of full breastfeeding.(16, 20) It should be noted that the sample sizes were smaller in these studies, and additionally, fewer confounding factors could be assessed.

In our study, infants introduced to formula in addition to breast milk before 4 months had increased risk for infections, which was not found for later formula introduction or for solid foods. The difference between formula and solids as regards infection risk is in accordance with observations from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. (6) In the EAT trial, the main difference between the two intervention arms was early introduction of solids, with no difference found for infections except for URTI.(19) We speculate that the observed difference in our study could be due to a relatively higher impact on the volume of breast milk given when formula was introduced at an early age, but our data do not provide the granularity to study this in more detail.

The strongest association observed in the full cohort analysis was the increased risk of hospitalisation for gastroenteritis in non-breastfed or infants breastfed for ≤6 months compared to ≥12 months. Observational studies elsewhere have found lower risk for gastroenteritis early in life among breastfed infants,(17, 21) also supported by the randomized trial from the Belarus.(22)

For lower respiratory tract infections, observational studies report conflicting results.(14, 17, 21) The only randomized controlled trial from an industrialized country did not find any difference in risk for LRTI or hospital admission between the group promoted to breastfeeding versus controls.(22) The full cohort analysis in our study suggests a higher risk of hospitalisation for LRTI if breastfeeding lasts ≤4 compared to ≥12 months.

The novel sibling analysis suggested that the associations observed in the full cohort could be biased by residual or unobserved confounding from shared maternal factors. In principle, this matched design eliminates confounding from factors fully shared by the siblings, such as maternal genotype, and reduces confounding from factors likely to be highly correlated among siblings such as rearing practices and parental reporting bias of the infections. However, the reduced sample size in the cohort belonging to siblings implies wider confidence intervals in the sibling analyses. A matched design has inherent limitations, with the possibility of increasing bias by non-shared confounders.(23) Therefore, we cannot automatically conclude that the sibling design produces a less biased result. Nevertheless, our interpretation of the findings among siblings is that the mother may be more important for the infection risk than the feeding mode, consistent with another recent sibling study on breastfeeding and a multitude of other long-term outcomes.(24) This study did not assess the risk of infections.

Few studies have assessed the potential benefit of the WHO recommended breastfeeding after 12 months with regard to infections,(3) the observation period has been limited to 6–12 months.(14, 17, 20–22, 25) We found similar risk for hospitalisation in infants breastfed for 6–11 months compared to ≥12 months. This finding suggests that breastfeeding plays a minor role in infection prevention after 12 months.

Our study is the largest prospective birth cohort of infant feeding and infections to date, with the potential of more precise estimates as compared to previous studies. Data collected in this study allowed for the assessment of multiple potential confounders, which reduces the risk of overestimating the potential effects of breastfeeding due to the associated healthy behaviours. The data collection of exposures and outcomes in a recall time period limited to 6–12 months reduces the risk of bias, and other studies have shown good agreement with retrospective breastfeeding data and 24-hour recall.(26, 27) Infectious symptoms occurring close to changes in diet could be more likely to be notified by the parents. As infections occurred and infant feeding were given in the same time intervals, reverse causation with infections influencing on breastfeeding cannot be ruled out. A serious infection could lead to interruption of breastfeeding and thus overestimate the apparent benefits of breastfeeding. Alternatively, motivation for breastfeeding could be increased with frequent infections, potentially underestimating the benefits.

A potential limitation of our study is that the difference in adjacent groups for duration of breastfeeding may be too small to induce detectable associations. However, comparing full breastfeeding for 3–4 months against 6 months (omitting 5 months) led to essentially the same conclusions (data not shown). The time of infection within each interval was not specified in the questionnaires, leading to an inability to determine this more accurately.

Our results are likely generalisable to industrialised countries with a similar burden of infectious disease and breastfeeding coverage. A higher background risk of infections in low- and middle income countries could explain differing results in less resourced populations.(11–13, 28, 29) Participants in our cohort study tend to have a higher level of education and age than the general population, and the participants lost during the study similarly were younger and less educated. In general, the associations between exposures and outcomes have been shown to be robust to selection bias.(30) A more heterogeneous cohort will also be more prone to confounding effects of i.e. socioeconomic differences.

The recommendations for infant feeding need to take all aspects of the health of the child and the mother into account. Health outcomes later in life as allergies, asthma, autoimmune diseases, neurodevelopment and obesity are important considerations and may be associated to the duration of breastfeeding. Our findings, supported by the sibling analysis, suggest that effects of prolonged breastfeeding may be overestimated by the healthy behaviour among mothers who follow the official recommendations for infant feeding.

To conclude, introduction of complementary foods from 4–6 months as compared to introduction ≥6 months of age in breastfed infants was not a significant risk factor for hospitalisation due to infections. Infections thus do not seem to be of major importance for these two alternative recommendations for introduction of complementary foods in a high-income society. However, our results do support the recommendation to fully breastfeed for 4 months and to continue breastfeeding beyond 6 months, and suggest that protection against infections is limited to the first 12 months.

Supplementary Material

What is known

Breastfeeding from birth may protect against infections, but optimal duration of breastfeeding is unclear.

Delaying introduction of complementary foods may reduce the risk of infections, but may be more important for formula than for solid foods.

Breastfeeding is associated with a healthy lifestyle in high-income countries, making interpretation of breastfeeding studies difficult.

What is new

Breastfeeding for ≤6 compared to ≥12 months was associated with higher risk of infections, but with similar risks for 6–11 and ≥12 months’ duration.

Breastfed children who received complementary foods at 4–6 months of age had similar risk for infection as those receiving complementary foods after 6 months.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participating families in Norway who take part in this on-going cohort study.

Grant support: The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study is supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services and the Ministry of Education and Research, NIH/NIEHS (contract no N01-ES-75558), NIH/NINDS (grant no.1 UO1 NS 047537-01 and grant no.2 UO1 NS 047537-06A1). The study was funded by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Dr Størdal was supported by an unrestricted grant from Oak Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: None of the authors have conflicts of interest to declare, and the funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

References

- 1.Fewtrell M, Wilson DC, Booth I, et al. Six months of exclusive breast feeding: how good is the evidence? BMJ. 2010;342:c5955. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van’t Hof MA, Haschke F. The Euro-Growth Study: why, who, and how. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31(Suppl 1):S3–13. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200007001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization WH. Infant and young child nutrition. http://apps.who.int/gb/archive/pdf_files/WHA55/ewha5525.pdf.

- 4.McGuire S, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2011. Adv Nutr. 2011;2:523–4. doi: 10.3945/an.111.000968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e827–e41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quigley MA, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Infant feeding, solid foods and hospitalisation in the first 8 months after birth. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:148–50. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.146126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Øverby NC, Kristiansen AL, Andersen LF, et al. Spedkost 6 måneder. 1908 http://helsedirektoratet.no/publikasjoner/anbefalinger-for-spebarnsernering/Sider/default.aspx. Accessed 8/7/13 AD.

- 8.World Health Organization DoNfHaD. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: Report of an expert consultation. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/nhd_01_09/en/

- 9.Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8(CD003517) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003517.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duijts L, Ramadhani MK, Moll HA. Breastfeeding protects against infectious diseases during infancy in industrialized countries. A systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2009;5:199–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2008.00176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan MU. Breastfeeding, growth and diarrhoea in rural Bangladesh children. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr. 1984;38:113–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khadivzadeh T, Parsai S. Effect of exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding on infant growth and morbidity. East Mediterr Health J. 2004;10:289–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen RJ, Brown KH, Canahuati J, et al. Effects of age of introduction of complementary foods on infant breast milk intake, total energy intake, and growth: a randomised intervention study in Honduras. Lancet. 1994;344:288–93. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91337-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rebhan B, Kohlhuber M, Schwegler U, et al. Breastfeeding duration and exclusivity associated with infants’ health and growth: data from a prospective cohort study in Bavaria, Germany. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:974–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haggkvist AP, Brantsaeter AL, Grjibovski AM, et al. Prevalence of breast-feeding in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study and health service-related correlates of cessation of full breast-feeding. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:2076–86. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010001771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chantry CJ, Howard CR, Auinger P. Full breastfeeding duration and associated decrease in respiratory tract infection in US children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:425–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duijts L, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, et al. Prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of infectious diseases in infancy. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e18–e25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnus P, Irgens LM, Haug K, et al. Cohort profile: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:1146–50. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perkin MR, Logan K, Tseng A, et al. Randomized Trial of Introduction of Allergenic Foods in Breast-Fed Infants. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1733–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oddy WH, Sly PD, de Klerk NH, et al. Breast feeding and respiratory morbidity in infancy: a birth cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:224–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.3.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quigley MA, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Breastfeeding and hospitalization for diarrheal and respiratory infection in the United Kingdom Millennium Cohort Study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e837–e42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer MS, Chalmers B, Hodnett ED, et al. Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): a randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA. 2001;285:413–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frisell T, Oberg S, Kuja-Halkola R, et al. Sibling comparison designs: bias from non-shared confounders and measurement error. Epidemiology. 2012;23:713–20. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31825fa230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colen CG, Ramey DM. Is breast truly best? Estimating the effects of breastfeeding on long-term child health and wellbeing in the United States using sibling comparisons. Soc Sci Med. 2014;109:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paricio Talayero JM, Lizan-Garcia M, Otero PA, et al. Full breastfeeding and hospitalization as a result of infections in the first year of life. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e92–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burnham L, Buczek M, Braun N, et al. Determining length of breastfeeding exclusivity: validity of maternal report 2 years after birth. J Hum Lact. 2014;30:190–4. doi: 10.1177/0890334414525682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Natland ST, Andersen LF, Nilsen TI, et al. Maternal recall of breastfeeding duration twenty years after delivery. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:179. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dewey KG, Cohen RJ, Brown KH, et al. Age of introduction of complementary foods and growth of term, low-birth-weight, breast-fed infants: a randomized intervention study in Honduras. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:679–86. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onayade AA, Abiona TC, Abayomi IO, et al. The first six month growth and illness of exclusively and non-exclusively breast-fed infants in Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2004;81:146–53. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v81i3.9145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilsen RM, Vollset SE, Gjessing HK, et al. Self-selection and bias in a large prospective pregnancy cohort in Norway. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23:597–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.