NESH, a member of ABL interactor (ABI) protein family that interacts and inhibits the ABL kinase, can suppress ectopic metastasis of tumor cells. Also the imatinib mesylate is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the ABL. Contrary to our expectation for their synergistic effects, the use of imatinib to treat NESH‐expressed cancer cells greatly enhances its invasive tumor growth in vivo. Our data strongly suggest that ABI protein expression including NESH should be checked before applying imatinib in order to know the validity.

The imatinib mesylate, a selective small‐molecule inhibitor of protein tyrosine kinases including ABL, KIT, and platelet‐derived growth factor receptor, specifically inhibits the proliferation of BCR–ABL‐expressing cells (Neering et al., 2007), and it has successfully been introduced in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) (O'Dwyer et al., 2003). The BCR–ABL protein functions as a constitutively activated tyrosine kinase, and this activity is required for the transforming function of the BCR–ABL protein of CML (Danial and Rothman, 2000). The ABI proteins, which bind the ABL, are phosphorylated by the ABL and suppress the ABL transforming activity without directly inhibiting the ABL kinase activity (Shi et al., 1995; Dai and Pendergast, 1995). When the interaction between the ABL and the ABI is blocked, the tyrosine kinase is activated and it increases the transforming properties. In addition to ABI‐1 and ABI‐2, mammals possess a third family member, NESH, which was characterized by our previous work (Miyazaki et al., 2000; Hirao et al., 2006). NESH, like ABI‐1 and ABI‐2, is a component of the ABI/WAVE/complex, but plays a different role in the regulation of ABL kinase. Because the forced expression of NESH suppressed cancer cell invasion and metastasis (Ichigotani et al., 2002), we anticipated a possible synergistic role of imatinib treatment and NESH expression on an effect of tumor suppression.

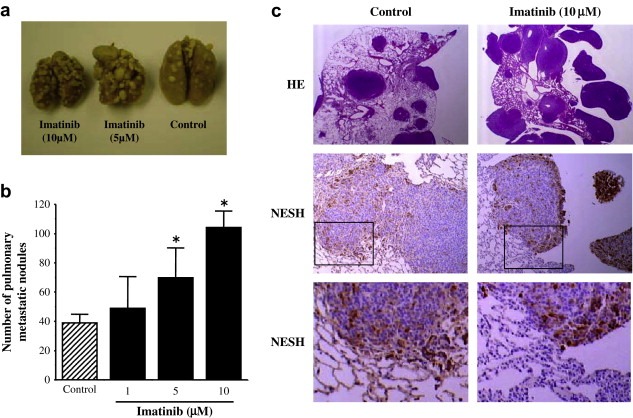

We introduced wild‐type NESH cDNA into v‐Src transformed NIH3T3 cells (NESH/SRD) (Ichigotani et al., 2002). To explore the role of imatinib for the reduction of tumor metastasis formed by the NESH/SRD cells, we assayed lung colonization by the tumor cells after tail vein injection, which is a widely used model system for vascular metastasis (Sossey‐Alaoui et al., 2007). The incidence of lung tumors reflects the metastatic potential of the injected cells. Syngeneic BALB/cAJcl−nu mice were injected with the SRD parental cell line as well as NESH/SRD clones in the presence of imatinib. Mice were sacrificed 3 weeks later when mice became symptomatic, then lung weight and the number of tumor nodules in the lung were evaluated. We found that the number of tumor nodules of NESH/SRD cells with imatinib was significantly increased compared with that of controls (Figure 1a and b). In addition, histological study of the lung tissues showed that the invaded tumor cells still expressed NESH as well as control tumor (Figure 1c), indicating no selection with imatinib for cells that escaped NESH protein expression. Similar results were obtained using either BCR–ABL‐ or ERBB2‐transformed cells with imatinib treatment and NESH expression. Because ABL kinase is activated downstream of EGFR and SRC kinases in fibroblasts (Plattner et al., 1999), ABL kinase may increase tumor cell migration and/or invasion (Srinivasan and Plattner, 2006). The overall survival of mice harboring tumors with imatinib treatment was worse at a dose dependent manner rather than untreated counterparts (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Enhanced lung metastasis of NESH‐expressed cells by imatinib treatment. (a) Photograph of metastatic nodules in the lungs from six‐week‐old male BALB/cAJcl−nu mice after tail vein injection of NESH/SRD cells with or without treatment of the imatinib at the indicated concentration for 4h in vitro. (b) Number of metastatic nodules with (black bar) or without (hatched) imatinib treatment. Data are represented as the mean S.D. of four mice in each group (*P<0.01). (c) Lung tissue sections from NESH/SRD‐implanted mice were stained with HE (upper) or with antibody to NESH for detection of NESH expression (middle and lower). The blocked box in middle panel indicates the region shown in the high‐powered view in the lower panel.

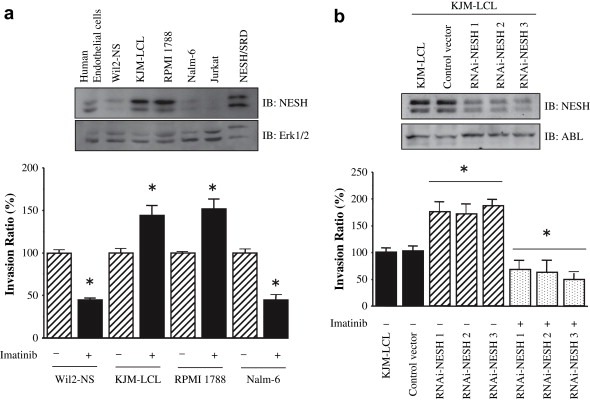

Checking NESH expression level among several lymphoid cell lines (Figure 2a), invasion assay with or without imatinib treatment was next performed in vitro. The Wil2‐NS and Nalm‐6 cells, those had low NESH expression, showed that imatinib effectively reduced the cell invasion activity. In contrast, KJM‐LCL and RPMI 1788 cells, those had higher NESH expression, showed that imatinib significantly enhanced the invasion. These are consistent with the previous observations in Figure 1. We asked whether selective reduction of NESH protein level was sufficient to confer valid susceptibility to imatinib, we used RNA interference (RNAi) technology to knockdown the expression of NESH. We constructed NESH RNAi vectors with a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression cassette that targeted human NESH. By transfecting these constructs into the KJM‐LCL cell line, we were able to establish three stable clones in which NESH expression was significantly down‐regulated. Using anti‐phospho‐ABL antibodies to monitor the activation–reduction status of ABL kinase, we found no significant reduction‐differences among the selected clones under the basal condition (data not shown), in agreement with previous studies (Jung et al., 2008). As shown in Figure 2b, these clones resulted in the increased invasion ratio without imatinib treatment, whereas the empty vector did not. In contrast, imatinib efficiently reduced invasion ratio on the NESH‐knockdown KJM‐LCL cells. Parallel studies of NESH‐knockdown in RPNI 1788 cells gave similar results (data not shown). Collectively, these results support the notion that NESH protein induction significantly enhances the metastatic potential of the cancer cells when treated with imatinib, and vice versa that imatinib treatment may exacerbate cancer in which NESH protein is expressed.

Figure 2.

NESH and imatinib synergistically enhanced the cell invasion. (a) The indicated cells were preincubated with or without imatinib (10μM) for 4h and allowed to invasion assay. Data are the means±SE of four separate experiments (*P<0.001). Inset shows endogenous NESH expression and Erk1/2 as a control for loading protein levels. (b) Invasion assays performed on KJM‐LCL cells transfected with either siRNA‐NESH (hatched or dotted bar) or vectors (black). NESH expression in KJM‐LCL was reduced by transfection of plasmids encoding siRNA‐NESH. Data are the means±SE of four separate experiments (*P<0.001). To generate NESH siRNA, we designed three constructs (RNAi‐NESH1, RNAi‐NESH2, RNAi‐NESH3) that recognize three target sites at nucleotides 791, 983 and 1434 downstream of the start codon of the NESH (GenBank accession no. AB037886). Three oligonucleotides containing sequences encoding RNAi‐NESH1 (AGTGGTGACACTGTACCCA), RNAi‐NESH2 (CATGCATATGGAGAAGGTG) or RNAi‐NESH3 (GAACAGGCACCCTGTCTCG) were cloned into the BamHI and Hind III sites of the pSilencer 3.1‐H1 neo vector (Ambion). Inset shows expression of NESH and ABL as a control.

Tumor metastasis is a highly organized dynamic multistep process involving decreased adhesion to the primary region, increased migration, as well as the establishment of the tumor colony at the distant site. In order to metastasize, a variety of molecules function and interact with each other through the multiple functional domains including Src‐homology domains, which both ABL and ABIs have at their terminal region. NESH as well as ABIs is localized to the edge of lamellipodial protrusions (Hirao et al., 2006). An unknown anti‐metastasis pathway in which ABIs are involved might be regulated by ABL kinase. On the other hand, imatinib did not affect the invasive capacity of normal endothelial cells and HUVEC cells (data not shown), in which endogenous NESH expression level was high (Figure 2a). It is also probable that more factors, such as proteolytic enzymes, might be involved in these effects.

What is the mechanism if imatinib enhanced cancer invasion? Imatinib has revolutionized the treatment of CML, particularly in patients who are not candidates for bone marrow transplantation. Although responses are seen in all phases of the disease, durable responses are most common in earlier stage patients. In spite of the exciting therapeutic results with imatinib in CML and gastrointestinal stromal tumors, however, recent studies had shown that imatinib exhibited undesirable adverse effects on the development of cancer cells (Garipidou et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2005). In some cases, unexpected rapid progression of metastatic carcinoma was observed within short periods during imatinib treatment. Imatinib also exhibited a small stimulatory effect on the proliferation of multiple myeloma cells through activation of the Erk1/2 protein kinases (Pandiella et al., 2003). Our data also argue for caution in the use of imatinib as therapeutic agents, as has been suggested. The important implication of the present study lies in the development of obvious distinction and accessibility for clinical application of imatinib. Further in vivo and in vitro studies on molecular pathways will be necessary to decipher the full mechanisms of action.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants‐in‐aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan and Nara Women's University Intramural Grant for Project Research.

Matsuda Satoru, Ichigotani Yasukatu, Okumura Naoko, Yoshida Hitomi, Kajiya Yuka, Kitagishi Yasuko, Shirafuji Naoki, (2008), NESH protein expression switches to the adverse effect of imatinib mesylate, Molecular Oncology, 2, doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.03.003.

References

- Dai, Z. , Pendergast, A.M. , 1995. Abi-2, a novel SH3-containing protein interacts with the c-Abl tyrosine kinase and modulates c-Abl transforming activity. Genes Dev 9, 2569–2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danial, N.N. , Rothman, P. , 2000. JAK-STAT signaling activated by Abl oncogenes. Oncogene 19, 2523–2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garipidou, V. , Vakalopoulou, S. , Tziomalos, K. , 2005. Development of multiple myeloma in a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia after treatment with imatinib mesylate. Oncologist 10, 457–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao, N. , Sato, S. , Gotoh, T. , Maruoka, M. , Suzuki, J. , Matsuda, S. , Shishido, T. , Tani, K. , 2006. NESH (Abi-3) is present in the Abi/WAVE complex but does not promote c-Abl-mediated phosphorylation. FEBS Lett 580, 6464–6470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichigotani, Y. , Yokozaki, S. , Fukuda, Y. , Hamaguchi, M. , Matsuda, S. , 2002. Forced expression of NESH suppresses motility and metastatic dissemination of malignant cells. Cancer Res 62, 2215–2219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.H. , Pendergast, A.M. , Zipfel, P.A. , Traugh, J.A. , 2008. Phosphorylation of c-Abl by protein kinase Pak2 regulates differential binding of ABI2 and CRK. Biochemistry 47, 1094–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.H. , Yen, R.F. , Jeng, Y.M. , Tzen, C.Y. , Hsu, C. , Hong, R.L. , 2005. Unexpected rapid progression of metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma during treatment with imatinib mesylate. Head Neck 27, 1022–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, K. , Matsuda, S. , Ichigotani, Y. , Takenouchi, Y. , Hayashi, K. , Fukuda, Y. , Nimura, Y. , Hamaguchi, M. , 2000. Isolation and characterization of a novel human gene (NESH) which encodes a putative signaling molecule similar to e3B1 protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 1493, 237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neering, S.J. , Bushnell, T. , Sozer, S. , Ashton, J. , Rossi, R.M. , Wang, P.Y. , Bell, D.R. , Heinrich, D. , Bottaro, A. , Jordan, C.T. , 2007. Leukemia stem cells in a genetically defined murine model of blast-crisis CML. Blood 110, 2578–2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dwyer, M.E. , Mauro, M.J. , Druker, B.J. , 2003. STI571 as a targeted therapy for CML. Cancer Invest 21, 429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandiella, A. , Carvajal-Vergara, X. , Tabera, S. , Mateo, G. , Gutiérrez, N. , San Miguel, J.F. , 2003. Imatinib mesylate (STI571) inhibits multiple myeloma cell proliferation and potentiates the effect of common antimyeloma agents. Br J Haematol 123, 858–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plattner, R. , Kadlec, L. , DeMali, K.A. , Kazlauskas, A. , Pendergast, A.M. , 1999. c-Abl is activated by growth factors and Src family kinases and has a role in the cellular response to PDGF. Genes Dev 13, 2400–2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. , Alin, K. , Goff, S.P. , 1995. Abl-interactor-1, a novel SH3 protein binding to the carboxy-terminal portion of the Abl protein, suppresses v-abl transforming activity. Genes Dev 9, 2583–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sossey-Alaoui, K. , Safina, A. , Li, X. , Vaughan, M.M. , Hicks, D.G. , Bakin, A.V. , Cowell, J.K. , 2007. Down-regulation of WAVE3, a metastasis promoter gene, inhibits invasion and metastasis of breast cancer cells. Am J Pathol 170, 2112–2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, D. , Plattner, R. , 2006. Activation of Abl tyrosine kinases promotes invasion of aggressive breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 66, 5648–5655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]