Abstract

Germline mutations of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes confer a high life‐time risk of ovarian cancer. They represent the most significant and well characterised genetic risk factors so far identified for the disease. The frequency with which BRCA1/2 mutations occur in families containing multiple cases of ovarian cancer or breast and ovarian cancer, and in population‐based ovarian cancer series varies geographically and between different ethnic groups. There are differences in the frequency of common mutations and in the presence of specific founder mutations in different populations. BRCA1 and BRCA2 are responsible for half of all families containing two or more ovarian cancer cases. In population‐based studies, BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are present in 5–15% of all ovarian cancer cases. Often, individuals in which mutations are identified in unselected cases have no family history of either ovarian or breast cancer. The ability to identify BRCA1/2 mutations has been one of the few major success stories over the last few years in the clinical management of ovarian cancer. Currently, unaffected individuals can be screened for mutations if they have a family history of the disease. If a mutation is identified in the family, and if an individual is found be a mutation carrier, they can be offered clinical intervention strategies that can dramatically reduce their ovarian cancer risks. In some populations with frequent founder mutations screening may not be dependant on whether a mutation is identified in an affected relative.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, BRCA1, BRCA2

1. Introduction

Ninety percent of malignant ovarian tumours are epithelial. There are several different histological subtypes, the most common being serous, mucinous, endometrioid and clear cell tumours. Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the seventh most common cause of death due to cancer in women. Globally, there are about 200,000 new diagnoses and 120–130,000 deaths from the disease each year. Incidence rates vary in different populations; there are about 16 cases per 100,000 women in parts of Northern Europe, 11 cases per 100,000 women in the UK, and 2–3 cases per 100,000 women in Japan and Africa (reviewed in Elmasry and Gayther, 2007). About 70% of women with ovarian cancer are diagnosed with late stage disease (III/IV). This is mainly due to the lack of any obvious signs and symptoms that would indicate early stage disease. Survival in these women is poor and only ∼30% will survive more than 5 years. The most significant known risk factor is a family history of the disease; an individual with a first‐degree relative affected with ovarian cancer has a threefold increased risk of developing the disease (Stratton et al., 1998). Ovarian cancer occurs as part of three autosomal dominant familial syndromes; the breast/ovarian cancer, site‐specific ovarian cancer, and Lynch (hereditary non‐polyposis colorectal cancer) syndromes. It is estimated that 5–10% of EOC cases are due to these familial syndromes.

Two genes, BRCA1 (MIM#113705; Miki et al. 1994) and BRCA2 (MIM#600185; Wooster et al. 1995), confer high‐penetrance susceptibility to both ovarian and breast cancer. BRCA1 is located on chromosome 11q21 and BRCA2 on 13q12‐13. BRCA1 comprises 22 coding exons spanning 80kb of genomic DNA and has a 7.8kb transcript coding for an 1863 amino acid protein. BRCA2 comprises 26 coding exons, spanning 70kb of genomic DNA, has an 11.4kb transcript and codes for a 3418 amino acid protein. Both proteins function in the double strand DNA break repair pathway but may have additional functions (reviewed Yoshida and Miki, 2004; Gudmundsdottir and Ashworth, 2006). Finally, both genes appear to behave as tumour suppressor genes, consistent with Knudson's two‐hit hypothesis of gene inactivation in the initiation of cancer epitomised by Retinoblastoma (Smith et al., 1992; Collins et al., 1995).

Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been found throughout the entire coding region and at splice sites. The majority of mutations in both genes are small insertions or deletions resulting in a frameshift, nonsense mutations or splice site alterations, which cause premature protein termination. A few functionally relevant missense mutations have also been reported. A multitude of unclassified variants (non‐synonymous coding changes or in‐frame deletions) that do not appear to be deleterious have also been detected. Until recently, only the coding region and splice sites of these genes were routinely screened for mutations. However, several groups have now identified large genomic deletions and rearrangements within both genes that would not have been identified by standard PCR based approaches (reviewed in Mazoyer, 2005). Large genomic alterations have been found to be relatively common in some populations with 8–40% of all BRCA1 mutations identified in families from the UK, USA, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy. The Breast Cancer Information Core (BIC) (http://research.nhgri.nih.gov/bic/) catalogues mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2; currently there are ∼12,000 carriers of a BRCA1 mutation or unclassified variant and ∼11,000 BRCA2 carriers recorded.

2. BRCA1 and BRCA2 analysis in ovarian cancer families

The majority of families with multiple cases of breast and ovarian cancer have inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 (Ford et al., 1998; Gayther et al., 1999; Ramus et al., 2007). The cumulative life‐time risks of ovarian cancer associated with these genes calculated from meta‐analysis of family studies was estimated to be 40–53% for a BRCA1 mutation carriers and 20–30% in BRCA2 carriers (Ford et al., 1998; Antoniou et al., 2002). However, these risk estimates appear to vary between studies, which may partly be due to ascertainment bias. In most familial studies containing cases of ovarian cancer, ascertainment was based on the occurrence of breast cancer in families with ovarian cancer reported as a secondary phenotype.

In this review of familial ovarian cancer, we focus on studies containing at least 60 families in which one or more cases of ovarian cancer have been ascertained (13 studies in total; Table 1). The frequency with which mutations were identified between these studies varies considerably. This is partly due to differences in the methods used for mutation screening. Some studies are based on populations with founder mutations that tend to skew the data. Finally, the thoroughness of patient ascertainment may also be a contributory factor. By way of example, in a study of two different series of ovarian cancer families, one from the UK and one from the US, the mutation screening methods were the same and performed in the same laboratory; but the frequency of BRCA1 mutations was much higher in the UK study. This may be due to the occurrence of a common BRCA1 founder mutation in the UK which was not found in the US study (ex13ins6kb; Ramus et al., 2007). The highest frequency of BRCA1/2 mutations was detected in a study from the USA, in which an identifiable deleterious mutation was found in 84% of families (Sinilnikova et al., 2006). This may be have been due to the large numbers of cases in families in this study; there were an average of 4.9 breast and 2.8 ovarian cancer cases per family.

Table 1.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies in studies of families with breast and ovarian cancer or ovarian cancer only.

| Country | Study | Screen | # Cases ovary | # BRCA1 | #BRCA2 | Ratio BRCA1:2 | Freq BRCA1 | Freq BRCA2 | Freq mut |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | Ramus et al., 2007 | A | 146 | 65 | 11 | 5.9:1 | 44.5 | 7.5 | 52.1 |

| USA | Ramus et al., 2007 | A | 137 | 39 | 14 | 2.8:1 | 28.5 | 10.2 | 38.7 |

| UK | Evans et al., 2008 | A | 424 | 110 | 56 | 2:1 | 25.9 | 13.2 | 39.1 |

| Denmark | Gerdes et al., 2006 | A | 110 | 37 | 12 | 3.1:1 | 33.6 | 10.9 | 44.5 |

| Sweden | Bergman et al., 2005 | A | 62 | 41 | 1 | 41:1 | 66.1 | 1.6 | 67.8 |

| USA | Sinilnikova et al., 2006 | A | 63 | 48 | 5 | 9.6:1 | 76.2 | 7.9 | 84.1 |

| USA | Frank et al., 2002 | B | 824 | 199 | 82 | 2.4:1 | 24.2 | 9.9 | 34.1 |

| Australia | Mann et al., 2006 | B | 236 | 73 | 33 | 2.2:1 | 30.9 | 14.0 | 44.9 |

| Spain | Díez et al., 2003 | B | 96 | 34 | 16 | 2.1:1 | 35.4 | 16.7 | 52.1 |

| Germany | Meindl, 2002 | B | 250 | 108 | 24 | 4.5:1 | 43.2 | 9.6 | 52.8 |

| Poland | Górski et al., 2004a,b | B | 100 | 62 | 1 | 62:1 | 62.0 | 1.0 | 63.0 |

| Poland | Menkiszak et al., 2003 | C(3) | 177 | 58 | − | − | 32.8 | − | − |

| Netherlands | Verhoog et al., 2001 | D + C(5) | 149 | 67 | 9 | 7.7:1 | 45.0 | 6.0 | 51.0 |

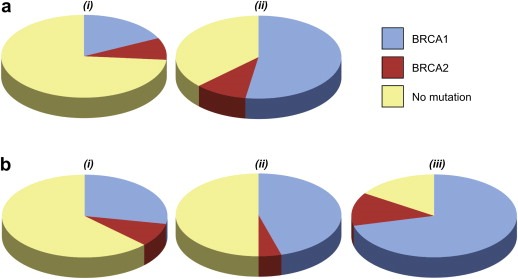

The type and extent of family history clearly influences the frequency with which mutations are detected. Of the studies reviewed here, only two (one of which included two familial ovarian cancer registries), selected families specifically on a basis of ovarian cancer (Ramus et al., 2007; Evans et al., 2008). In the familial ovarian cancer registry study, there was considerable variation in frequency of mutations when families were sub‐grouped into breast/ovarian cancer families or site‐specific ovarian cancer families, and then according to the number of cases within families (Figure 1). The BRCA1/2 mutation frequency was less in site‐specific ovarian cancer families compared to breast/ovarian cancer families. Combining the data from both registries, a BRCA1/2 mutation was identified in 30/37 families (81%) containing 3 or more cases of ovarian cancer and at least one breast cancer case, but in only 37/59 families (63%) containing 3 or more ovarian cancer cases and no breast cancer cases (Ramus et al., 2007). These data also show that the greater the number of ovarian cancer cases in the family, the more likely a BRCA1/2 mutation will be present. A mutation was found in 38/141 families (27%) containing 2 ovarian cancer cases only compared to 27/50 families (54%) containing 3 ovarian cancer cases only. These trends were generally replicated in other studies. A similar low frequency of mutation carriers (29%) in families with two confirmed cases of ovarian cancer only, and a high frequency of mutations with more extensive family history of cancer, was found in another study (Evans et al., 2008). In a study from the Netherlands 72/138 breast/ovarian cancer families (52%) had a BRCA1/2 mutation compared to 4/11 site‐specific ovarian cancer families (36%) (Verhoog et al., 2001). In Sweden, mutations were found in 7/10 (70%) ovarian cancer only families, whilst 31/42 (74%) families that also contained breast cancer cases <50 years had a mutation (Bergman et al., 2005). In the USA historical series of families, 12/17 (71%) families with 1 ovarian cancer case and any number of breast cancer cases had a mutation, compared to 41/46 families (89%) containing 2 or more ovarian cancer cases occurring within breast cancer families (Sinilnikova et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

Pie charts showing the proportion of families with BRCA1 (blue), BRCA2 (red) and no detectable mutation (yellow) in UK and USA familial ovarian cancer registries divided by type and extent of family history. (a) Higher proportion of families with mutations with increasing number of ovarian cancer cases i) 2 ovarian cancer cases only, ii) 3 or more ovarian cancer cases only. (b) Higher proportion of families with mutations with increasing number of breast cancer cases i) 2 or more ovary and no breast cancer, ii) 2 or more ovary and one breast cancer case, iii) 2 or more ovary and 2 or more breast cancer cases.

The ratio of BRCA1 to BRCA2 mutations appears to be greater when there are more ovarian cancer cases in a family. The mutation ratio was 2:1 in families containing 2 ovarian cancer cases and no breast and 5:1 in families containing 3 or more ovarian cancer cases and no breast cancer (Ramus et al., 2007). In a USA study the ratio was 2:1 in breast cancer families with one ovarian cancer case and 40:1 in breast cancer families with 2 or more ovarian cancer cases (Sinilnikova et al., 2006). Finally, several studies have suggested that a greater proportion of breast/ovarian cancer families have BRCA1 mutations than families containing breast cancer only (Verhoog et al., 2001; Meyer et al., 2003; Pohlreich et al., 2005; Sinilnikova et al., 2006). Two conclusions can be drawn from these studies: The first is that BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations represent the most significant high‐penetrance genetic risk factors for ovarian cancer; the second is that BRCA1/2 mutations are the major genetic risk factors for both of the previously defined syndromes, site‐specific ovarian cancer and the breast‐ovarian cancer.

2.1. Common or founder mutations

The Breast Cancer Information Core (BIC), which is a catalogue of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations identified around the world, reports that the most common BRCA1 mutations identified are 185delAG (16.5%), 5382insC (8.8%) and the missense alteration C61G (1.8%). The most commonly reported BRCA2 mutations are 6174delT (9.6%), K3326X (2.6%), 3036del4 (0.9)%, and 6503delTT (0.8%). There are, however, major differences in the frequency of specific mutations in different populations. Several different founder mutations have been described at high frequencies in families containing both ovarian and breast cancer from different countries (reviewed in Ferla et al., 2007). Some founder mutations are confined to geographically isolated regions or specific populations, whereas other founder mutations are common in several different countries suggesting spread by migration and possibly an older origin. For example, the BRCA1 mutation 5382insC is common throughout Europe and is thought to have arisen in the Baltic region approximately 38 generations ago.

The proportion of all mutations that are founder mutations in a population has major implications for the mutation detection strategies that are used to identify mutations, at both the research and clinical testing level. Mutation specific screening or a phased rather than full screening approach is possible in populations with a high percentage of founder mutations (Table 2). The most well characterised founder mutations are three alterations that occur in the Ashkenazi Jewish population, two in BRCA1 (185delAG and 5382insC) and one in BRCA2 (6174delT). These three mutations account for 98–99% of identified mutations in this population (Phelan et al., 2002; Frank et al., 2002). Screening for these three founder mutations alone is now part of routine clinical practice for Ashkenazi Jewish individuals. The screening for specific founder mutations is also practical in several other countries. In Iceland, BRCA1 mutations are rare and the 999del5 BRCA2 founder mutation is responsible for the vast majority of ovarian and/or breast cancer families in caused by these genes. Another example is the high frequency of the 5382insC BRCA1 mutation as well as the presence of other common mutations, which makes targeted screening possible in several Eastern European countries including Russia, Poland and Hungary (Sokolenko et al., 2007; Menkiszak et al., 2003; Van Der Looij et al., 2000). In Sweden, six mutations, including 3172ins5 and 1201del11 in BRCA1, accounted for 75% of mutations in a clinical screening unit (Einbeigi et al., 2007). In Norway the BRCA1 1675delA and 1135insC mutations are particularly common, accounting for 3% of ovarian cancer cases and it has been suggested they could be offered in population‐based clinical testing (Dørum et al., 1999). A German study has suggested a stepwise mutation screening program, based on initial screening for the common mutations (Meindl, 2002). Finally, in Denmark, the 2594delC mutation has been shown to account for 18% of all BRCA1 mutations (Bergthorsson et al., 2001; Søgaard et al., 2008) and 7 mutations account for 35% of carriers.

Table 2.

Common founder mutations with a significant role in the population.

| Population | Number common mutations | BRCA1 | BRCA2 | Proportion of BRCA1/2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 3 | 185delAG | 6174delT | 98–99% of BRCA1/2 mutations |

| 5382insC | ||||

| Iceland | 1 | 995delG | Vast majority of BRCA1/2 mutations, 7.9% of ovarian cancer | |

| Russia | 1 | 5382insC | 94% of BRCA1 mutations, 11% of families | |

| Poland | 3 | 5382insC | 80% of BRCA1/2 mutations, 91% of BRCA1 mutations | |

| C61G, | ||||

| 4153delA | ||||

| Germany | 3 | 5382insC | 38% of BRCA1 mutations | |

| 300T>G | ||||

| Del ex 17 | ||||

| Germany | 18 | 66% of BRCA1 mutations | ||

| Hungary | 5 | 5382insC | 9326insA, 6174delT | 80 of BRCA1 mutations, 50 of BRCA2 mutations |

| 300T>G | ||||

| 185delAG | ||||

| Norway | 4 | 1675delA | 68 of BRCA1 mutations, 1675delA and 1135insA 3% of ovarian cancer | |

| 1135insA | ||||

| 816delGT | ||||

| 3347delAG | ||||

| Finland | 11 | IVS11+3A>G, C4446T | 9345+1G>A, C7708T, T8555G, 3604delTT | 84% of BRCA1/2 mutations |

| Sweden | 1 | 3171insC | 70% of BRCA1/2 mutations in West Sweden | |

| Denmark | 7 | 2594delC | 6601delA, 1538del4, 6174del4 | 35% of BRCA1/2 mutations |

| 3438G>T | ||||

| 5382insC | ||||

| 3828delT | ||||

| Netherlands | 4 | 2804delAA | 5579insA, 6503delTT | 24% of BRCA1/2 mutations, 5579insA and 6503delTT 62% of families |

| IVS12‐1643del3835 | ||||

| Netherlands | 2 | Deletion ex 13, Deletion ex 22 | 25% of BRCA1/2 mutations | |

| French | 2 | 3600del11, G1570X | 52% of BRCA1/2 mutations | |

| French Canadian | 7 | C4446T | 2816insA, G6085T, 8765delAG, 6503delTT | 8.9% of ovarian cancer |

| 2953del3+C | ||||

| 3768insA | ||||

| French Canada | 4 | C4446T, R144X | 8765delAG, 3398del5 | 8765delAG and 3398del5 1.3% of ovarian cancer |

| UK | 1 | ex13ins6kb | 9% of BRCA1 mutations |

It is possible that common founder mutations remain to be identified in some populations, because many studies have not screened for large rearrangement mutations. A BRCA1 rearrangement ‘ex13ins6kb’ is a UK founder and accounts for 9% of BRCA1 mutations in the UK (1999, 2007, 2000). Similarly, exon 13 and exon 22 deletion mutations are common in the Netherlands and together accounted for 25% of all BRCA1 mutations identified in one study (Petrij‐Bosch et al., 1997).

2.2. Variation in ovarian cancer risks in families with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations

The risks of ovarian and breast cancer can be vastly different in patients with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. It is clear that there are differences in disease penetrance for each gene. The variation in disease risks may be due to differences in exposure to environmental risk factors in different populations and/or shared within families. The underlying genetic background may also influence disease risk, and there are two plausible explanations as to how genetic factors can influence disease penetrance. The first is that different BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations lead to differences in the biology of the translated protein, and that these have different effects in normal breast and ovarian tissues. The second is that common moderate/low penetrance genes in the population can influence penetrance. The evidence from several studies suggests that the variations in disease risk that are observed are probably due to a combination of both of these factors.

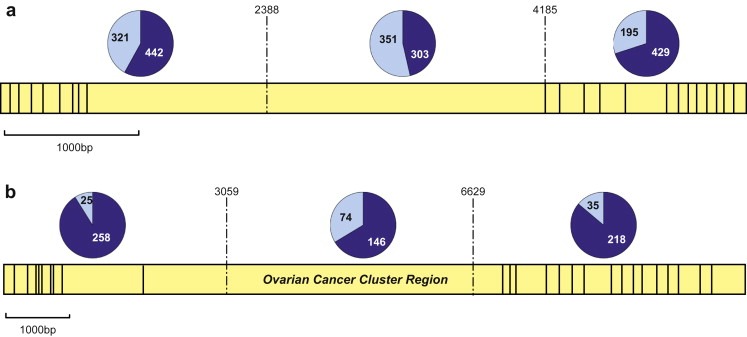

There is evidence that the location of mutations in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 can influence the risk of ovarian and/or breast cancer within families. For BRCA1, an initial study suggested that mutations located in the 5′ end of the gene were associated with higher risks of ovarian cancer compared to mutations in the 3′ end (Gayther et al., 1995). A more extensive study of 356 families analysed the association between mutation position and the ratio of breast to ovarian cancer, and has refined the initial observation. In this study, mutations in a central portion of the gene, spanning nucleotides 2401–4190, were associated with significantly lower breast cancer risks and/or higher ovarian cancer risks compared to mutations elsewhere in the gene (Figure 2) (Thompson et al., 2002a).

Figure 2.

Proportion of breast and ovarian cancer cases in families with mutations in the 5′, central and 3′ regions of each gene. Yellow indicates the exon structure of each gene and in the pie charts, dark blue are breast cancer cases and light blue are ovarian cancer cases. Data from Thompson et al. (2001, 2002a) and Ramus et al. (2007) (excluding overlapping families). (a) BRCA1; the ratio of breast to ovarian cancer in each region is 1.4, 0.9 and 2.2 respectively showing increased risk of ovarian cancer for mutations in the central region bounded by 2388–4185bp. (b) BRCA2; the ratio of breast to ovarian cancer in each region is 10.3, 2.0 and 6.2 respectively showing an even more pronounced increased risk of ovarian cancer (or decreased risk of breast cancer) for mutations in the central OCCR, bounded by 3059–6629bp.

A remarkably similar effect is seen in the BRCA2 gene. Gayther et al. (1997) initially reported that mutations in a portion of the gene termed the ovarian cancer cluster region (OCCR) were associated with a higher risk of ovarian cancer compared to breast cancer. This was confirmed in a larger study of 164 families; the ratio of breast cancer to ovarian cancer in families with a mutation in the OCCR, spanning a region from 3059 to 6629, was 3:2. Outside this region, the ratios of breast to ovarian cancer were 10.3 and 9.4 for mutations 5′ and 3′ of the OCCR respectively (Figure 2) (Thompson et al., 2001). Another study reported that families with ovarian cancer were significantly more likely to have mutations in the OCCR than the rest of BRCA2 (OR=2.2, P=0.0002) (Lubinski et al., 2004). This genotype phenotype correlation has been supported by a number of independent studies (Risch et al., 2001a; Neuhausen et al., 1998). However, some other studies show no significant differences on risk associated with these regions (Díez et al., 2003; Pal et al., 2005).

In support of these findings, different founder mutations appear to be associated with different levels of disease penetrance. For example, the BRCA2 6174delT mutation is associated with higher disease risks than the average for all other BRCA2 mutations (Antoniou et al., 2005). In another study, a founder BRCA1 mutation (4153delA) in Poland has been shown to be associated with high ovarian cancer risks but low breast cancer risks (Górski et al., 2004, 2004).

It remains unclear why different truncating mutations should cause different breast and ovarian cancer risks. For different length truncating mutations to have different effects on breast and ovarian epithelial cells, they must produce stable mutant proteins, despite reports suggesting that mutations in these genes lead to degradation of the mRNA by nonsense‐mediated decay (Perrin‐Vidoz et al., 2002; Ware et al., 2006). It has been speculated that for both BRCA1 and BRCA2, loss or retention of specific regions in each gene influences their interaction with proteins involved in double strand DNA break repair and in particular the RAD 51 protein (Scully et al., 1997; Bork et al., 1997).

The associations between disease risk and mutation location cannot explain why families with the same BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation also show variation in their disease risks. Genetic association studies for three common cancers (breast, prostate and colorectal) have recently shown that several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are common in the population are low/moderate penetrance risk factors for these cancers (Easton et al., 2007; Hunter et al., 2007; Tomlinson et al., 2008; Tenesa et al., 2008; Gudmundsson et al., 2008; Eeles et al., 2008). It follows then, that common genetic variation might also influence disease risks in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. The data so far are limited. In two small studies, common variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 were found not to significantly modify the risks of ovarian cancer in BRCA1 carriers (Ginolhac et al., 2003; Hughes et al., 2005). This subject is being addressed on a larger scale by the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (CIMBA) which aims to identify genetic modifiers of breast and ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers (Chenevix‐Trench et al., 2007). The consortium has gathered together approximately 3000 mutation carriers diagnosed with ovarian cancer (2400 BRCA1 carriers and 600 BRCA2 carriers) and approximately 11,800 mutation carriers with breast cancer (7500 BRCA1 and 4300 BRCA2) (personal communication with CIMBA). Currently a candidate gene approach is being used in a standard genetic association study design to identify genetic modifiers; but it is likely that a genome wide association study approach will be needed if these studies are to be successful.

2.3. Ovarian cancer families in which no BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation has been identified

In a study of 283 ovarian cancer families from two familial ovarian cancer registries, no mutation was identified in more than a third of families containing either three or more ovarian cancer cases only or >3 breast/ovarian cancer cases (Ramus et al., 2007). Mutation screening methodologies are unlikely to have identified all mutations present, but this is unlikely to account for all of these high‐risk families. In this study, linkage analysis in non‐BRCA1/2 families suggested that nearly half of these families showed evidence against linkage to the BRCA1 locus. Some families may not show strong evidence of linkage because they contain phenocopies (Richards et al., 1999) although this seems less likely for ovarian compared to breast cancer families simply because ovarian cancer is much less prevalent in the population (Ramus et al., 2007). The majority of BRCA1/2 negative families with limited family histories of ovarian cancer might represent chance clusters of ovarian cancer cases. Alternatively, some families could be due to several susceptibility alleles of more moderate penetrance that are common in the population (Pharoah et al., 2002). However, the absence of a mutation in families with multiple cases of ovarian cancer may suggest that other, as yet unidentified highly penetrant ovarian cancer susceptibility genes exist. A small number of families in both the UK and Gilda Radner (USA) familial ovarian cancer registries were found to have mutations in the mismatch repair gene, hMSH2 (personal communication Richard Dicioccio and Paul Pharoah). Mutations in other rare highly penetrant genes may also play a role in a subset of the BRCA1/2 negative families.

3. BRCA1/2 mutations in ovarian cancer cases unselected for a family history of disease

Several studies have now been published in which BRCA1 and BRCA2 were analysed in ovarian cancer cases unselected for a family history of the disease. Based on the thoroughness of the analysis, these studies can be divided into three categories: 1) Those that have analysed the entire coding region of either or both genes, some of which also screened for large genomic rearrangements; 2) Studies that have performed partial screening of either or both genes; 3) Studies that have only screened for common or founder mutations known to exist in the population. Where one or a few common mutations exist in a population, screening for these mutations is clearly a rapid and cost‐efficient approach to identify the majority of mutation carriers. We have reviewed the data from 12 studies for which complete gene analysis was performed (5 for BRCA1 and BRCA2, 6 for just BRCA1 and 1 for just BRCA2), 2 studies that performed a partial gene analysis and 19 studies that screened for known common/founder mutations. Of the 5 studies in which complete analysis of both genes was carried out, only one study also analysed these genes for large genomic rearrangements. The data from these studies, including the frequency with which mutations were identified are summarised in Table 3 and Figure 3.

Table 3.

Frequency of mutations in population‐based studies of ovarian cancer.

| Country | Study | Screen | # Cases | # BRCA1 | # BRCA2 | Ratio BRCA1:2 | Freq BRCA1 | Freq BRCA2 | Freq mut | Relatives breast or ovary | % Carriers with FH | Freq mut in ind with FH | Freq mut in ind no FH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | Søgaard et al., 2008 | A | 445 | 22 | 4 | 5.5:1 | 4.9 | 0.9 | 5.8 | 10% | 46.2 | 26.7 | 3.5 |

| Sweden | Malander et al., 2004 | B | 161 | 12 | 1 | 12:1 | 7.5 | 0.6 | 8.1 | 30% | 92 | 27.7 | 0 |

| Sweden | Einbeigi et al., 2007 | C (7) | 222 b | 42 | 0 | − | 18.9 | 0 | 18.9 b | − | − | − | − |

| Canada | Risch et al., 2001b | B | 977 | 75 | 54 | 1.4:1 | 7.7 | 5.5 | 13.2 | 25% | 62.8 | 25.9 | 7.0 |

| USA | Pal et al., 2005 | B | 209 | 20 | 12 | 1.7:1 | 9.8 | 5.7 | 15.3 | 47% | 68.8 | 22.2 | 9.1 |

| USA | Rubin et al., 1998 | B | 116 | 10 a | 1 a | 10:1 | 8.6 | 0.9 | 10 | − | − | − | − |

| USA | Berchuck et al., 1998 | B+ | 103 | 4 | − | − | 3.9 | − | − | − | 100 | − | − |

| USA | Anton‐Culver et al., 2000 | B+ or C (7) | 120 | 4 | − | − | 3.3 | − | − | 20.1% | 100 | 16 | 0 |

| USA | Smith et al., 2001 | B+ | 258 | 12 | − | − | 4.6 | − | − | 36.7% | 91.7 | 11.7 | 0.7 |

| USA | Takahashi et al., 1995 | B+ | 115 | 6 | − | − | 5.2 | − | − | − | 83 | − | − |

| USA | Takahashi et al., 1996 | B+ | 130 | − | 4 | − | − | 3.1 | − | − | 0 | 0 | − |

| UK | Stratton et al., 1997 | B+ | 355 | 12 | − | − | 3.4 | − | − | 5−10% | 75 | − | − |

| Japanese | Matsushima et al., 1995 | B+ | 76 | 3 | − | − | 3.9 | − | − | − | 50 | − | − |

| Pakistan | Liede et al., 2002 | D | 120 | 16 | 3 | 5.3:1 | 13.3 | 2.5 | 16 | 10% | − | − | − |

| Turkey | Yazici et al., 2002 | D | 102 | 10 | 7 | 1.4:1 | 9.8 | 6.9 | 17 | 14.7% | 23.5 | 26.7 | 14.9 |

| French Canada | Tonin et al., 1999 | C (7) | 99 | 5 | 3 | 1.7:1 | 5.1 | 3.0 | 8.1 | 38.4% | 87.5 | 18.4 | 1.6 |

| Finland | Sarantaus et al., 2001 | C (20) | 233 | 11 | 2 | 5.5:1 | 4.7 | 0.9 | 5.6 | 22% | 61.5 | 15.7 | 2.8 |

| Norway | Dørum et al., 1999 | C (2) | 615 | 18 | − | − | 2.9 | − | − | − | 87.5 | − | − |

| Norway | Bjørge et al., 2004 | C (4) | 478 | 19 | − | − | 39.7 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hungary | Van Der Looij et al., 2000 | C (5) | 90 | 10 | 0 | − | 11.0 | 0 | 11.0 | − | − | − | − |

| Iceland | Rafnar et al., 2004 | C (2) | 179 | 2 | 10 | 0.5:1 | 1.1 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 17% | 75.0 | 30.0 | 2.0 |

| Iceland | Johannesdottir et al., 1996 | C (1) | 38 | − | 3 | − | − | 7.9 | − | − | − | − | − |

| Poland | Menkiszak et al., 2003 | C (3) | 364 | 49 | − | − | 13.5 | − | − | 12.6% | 41 | 43.5 | 9.1 |

| Ashk Jewish | Boyd et al., 2000 | C (3) | 189 | 67 | 21 | 3.2:1 | 35.5 | 11.1 | 46.6 | − | − | − | − |

| Ashk Jewish | Moslehi et al., 2000 | C (3) | 208 | 57 | 29 | 2:1 | 27.4 | 13.9 | 40.2 | 64.9% | 76.3 | 60.0 | 27.7 |

| Ashk Jewish | Modan et al., 2001 | C (3) | 840 | 182 | 64 | 2.8:1 | 21.7 | 7.6 | 29.3 | 25.8% | − | − | − |

| Ashk Jewish | Ramus et al., 2001 | C (3) | 118 | 15 | 12 | 1.3:1 | 12.7 | 10.2 | 22.9 | − | − | − | − |

| Ashk Jewish | Satagopan et al., 2002 | C (3) | 382 | 103 | 44 | 2.3:1 | 27 | 12 | 39 | − | − | − | − |

| Ashk Jewish | Hirsh-Yechezkel et al., 2003 | C (3) | 563 | 201 | − | 35.7 | 35.7 | 14.2% | 18 | 55.0 | 32.5 | ||

| NonAshk Jewish | Hirsh-Yechezkel et al., 2003 | C (3) | 174 | 16 | − | 9.2 | 9.2 | 14.9% | 31.3 | 19.2 | 7.4 | ||

| All Jewish | Hirsh-Yechezkel et al., 2003 | C (3) | 779 | 172 | 57 | 3:1 | 21.5 | 7.1 | 28.6 | 14.9% | 23.1 | 45.7 | 26.5 |

A full screen including large genomic rearrangements, B full screen without large genomic rearrangements, C screen for known founder mutations with the number of founder mutations indicated in brackets, D partial screen. +, just BRCA1 screened; ±, just BRCA2 screened.

1 case with both a BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation.

cases with both breast and ovarian cancer.

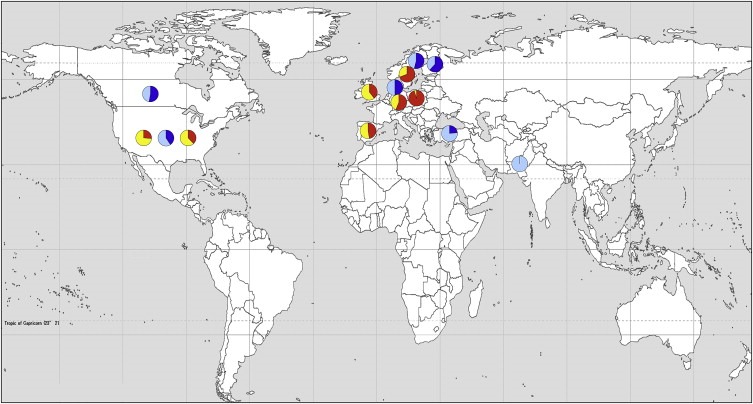

Figure 3.

Map of the world showing the proportion of detected BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations that are unique or identified multiple times within a study. The red and yellow pie charts indicate family based studies where red represents common mutations and yellow represents unique mutations. The blue pie charts represent population‐based studies where dark blue are common mutations and light blue are unique mutations. Studies included are those from Tables 1 and 3 that performed full screening of both genes, have greater than 10 mutations and have listed the mutations identified. Three studies with partial screening were also included (from Pakistan, Turkey and Finland). Some populations have a high proportion of common mutations ie. Poland and Sweden, while others have a high proportion of unique mutations ie. Pakistan, Turkey and USA.

For non‐Ashkenazi Jewish studies in which mutation analysis was performed for the complete coding region, the frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations ranged from 3 to 10% and from 0.6 to 6% respectively. When the data for both genes are combined, 6–15% of ovarian cancer cases have a mutation in either gene. It is well known that the frequencies of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are higher in Ashkenazi Jewish populations. For studies that screened for the founder mutations, mutation frequencies ranged from 12 to 36% for BRCA1 and 8–14% for BRCA2. BRCA1 mutations are more common in ovarian cancer cases than BRCA2 mutations, although the ratio of BRCA1 to BRCA2 varies between populations. In a Swedish study there were 12 times as many BRCA1 as BRCA2 mutations, whilst in a study from Canada the ratio was 1.4:1 (Malander et al., 2004; Risch et al., 2001b).

These wide‐ranging estimates of the mutation prevalence suggest genetic heterogeneity between different populations or ascertainment bias in the population collections. The presence of founder mutations, ethnically different populations and the completeness and accuracy of mutation screening will all affect the reported frequencies of mutations. It is likely that most population‐based studies will have under‐reported the true frequencies of BRCA1/2 mutations because mutations would have been missed, in particular those studies that did not screen for the presence of large genomic rearrangements.

The extent of family history in these population‐based series varies considerably; this is also likely to affect the population‐based estimates of BRCA1/2 mutation frequency. The number of cases reporting a first or second‐degree relative with breast or ovarian cancer in the non‐Ashkenazi Jewish studies ranged from 10 to 47%. Unsurprisingly, cases with a family history of ovarian and/or breast cancer are more likely to carry a BRCA1/2 mutation than those without; 23–100% of mutation carriers reported a family history. The more extensive the family history, the more likely it was that a mutation was present. In a Swedish study 92% of mutations carriers had a first or second‐degree relative with ovarian/breast cancer (Malander et al., 2004). In studies from the USA and Canada 62–69% of mutation carriers had a similar family history (Pal et al., 2005; Risch et al., 2001b). By contrast, only 22–28% of individuals that reported ‘any’ relative with ovarian/breast cancer were mutation carriers in the studies for which complete gene screening was performed.

Determining the frequency of mutations in individuals with no reported family history is an important aspect in understanding the penetrance of the disease (Table 3). In the studies with full screening of both genes 0–9.1% of individuals with no family history had a mutation (Malander et al., 2004; Søgaard et al., 2008; Risch et al., 2001b; Pal et al., 2005). An even higher proportion of Polish (9%) and Turkish (15%) cases with no family history had a mutation; and these are underestimates because only partial screening of the genes was performed (Menkiszak et al., 2003; Yazici et al., 2002). In two Ashkenazi Jewish studies 28–33% of individuals with no family history had mutations, while in the non‐Ashkenazi Jewish population 7% had mutations (Moslehi et al., 2000; Hirsh‐Yechezkel et al., 2003).

3.1. Risks of cancer in carriers identified in population‐based studies

From studies of high‐risk families the ovarian cancer risk by age 70 in BRCA1 carriers is 44–63% and in BRCA2 carriers 27–31% (reviewed Antoniou et al., 2003). These data are useful in the counselling of individuals with a significant family history of breast or ovarian cancer. However, population studies have shown that many mutation carriers have no affected first‐degree relatives with breast or ovarian cancer suggesting that ovarian cancer risk estimates for the general population are not as high as those calculated from familial studies. The ovarian cancer risks calculated from a meta‐analysis of 22 population‐based breast and/or cancer studies suggest much lower risks; the average cumulative risks of ovarian cancer by age 70 in BRCA1 carriers were 39% (18–54) and in BRCA2 mutation carriers 11% (2.4–19) (Antoniou et al., 2003). A recent meta‐analysis found ovarian cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers to be 40% and 18% respectively (Chen and Parmigiani, 2007). The risks of ovarian cancer were also found to differ by mutation; by age 70 the risks were 14% in carriers with the 185delAG mutation, 33% in individuals with the 5382insC mutations (both in BRCA1) and 20% in individuals with the 6174delT BRCA2 mutation. The ovarian cancer risk, for carriers of the 6174delT mutation, was higher than the average for BRCA2 (11%), supporting findings that mutations in the OCCR are associated with higher ovarian cancer risk. As well as the increased risk of ovarian cancer, carriers also have an increased risk of breast cancer. From meta‐analyses the average cumulative risk for breast cancer by age 70 is 57–65% for BRCA1 carriers and 45–49% for BRCA2 carriers (Antoniou et al., 2003; Chen and Parmigiani, 2007).

Some studies have also looked at the risks of other cancer associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2. In a study of 699 families with BRCA1 mutations it was found that female carriers have a small increased risk of cancer overall with a relative risk of 2.3 (P=0.001) (Thompson et al., 2002b). There was an increased risk of cancer of the pancreas, uterus and cervix, and also some evidence for an increased risk of prostate cancer in male carriers, but only if diagnosed under 65 years. The risk of fallopian tube and peritoneal cancer was similar to that of ovarian cancer. For carriers of BRCA2 mutations, a study of 173 families showed strong evidence for an increased risk of prostate and pancreatic cancer and some evidence for an increased risk in stomach, gallbladder and bile duct and malignant melanoma (Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium, 1999). As with BRCA1, the relative risk of prostate cancer in male BRCA2 carriers was higher for a diagnosis under 65 years. It has been suggested that there is a lower risk in individuals with mutations in the OCCR. A meta‐analysis of 30 studies showed an increased risk for ‘all cancer’ (after excluding breast and ovarian cancer) for carriers and an increased risk of cancer of the stomach, pancreas, prostate and colon (Friedenson, 2005).

4. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of BRCA1/2 carriers

The majority of studies have consistently shown that individuals carrying a BRCA1 mutation are diagnosed with ovarian cancer at an earlier age than non‐carriers with an average of 7 years difference across 7 different studies (Tonin et al., 1999; Anton‐Culver et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2001; Yazici et al., 2002; Menkiszak et al., 2003; Pal et al., 2005; Søgaard et al., 2008). Some studies have suggested that BRCA2 carriers are diagnosed at a later age; however the numbers of carriers in these studies are small (Takahashi et al., 1996; Tonin et al., 1999; Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium, 1999). Other studies suggest BRCA2 carriers are diagnosed at a younger age but are not significantly different; again this is probably due to too small numbers of carriers analysed (Rafnar et al., 2004). In a Danish study, a significant decrease in the frequency of BRCA1 mutation carriers with increasing age at diagnosis was observed; this trend appears to be consistent with another study from Canada (Risch et al., 2001b).

The use of oral contraceptives (OC) has been shown to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer in the general population (Whittemore et al., 1992). In a study of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers it has also been shown that OC use reduces the risk of ovarian cancer by 5% with each year of use (Whittemore et al., 2004). With 6 or more years of use the odds ratio is 0.62 (0.35–1.09). In a larger study, OC use significantly reduced the risk of ovarian cancer in BRCA1 carriers (OR 0.56 (0.45–0.71) p<0.0001) and in BRCA2 carriers (OR 0.39 (0.23–0.66) p=0.0004) (McLaughlin et al., 2007). The same study found that parity was associated with a decreased risk in BRCA1 carriers but an increased risk in BRCA2 carriers, while breast‐feeding was associated with a decreased ovarian cancer risk in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers (McLaughlin et al., 2007). A study of Ashkenazi Jewish women showed that there was a decreased risk of ovarian cancer in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with each birth (Modan et al., 2001).

It has been suggested that invasive ovarian cancers from BRCA1 mutation carriers are more likely to be serous compared to non‐BRCA1 tumours. In a study of 442 ovarian cancer cases with pathological review, 44% of tumours from 178 BRCA1 mutation carriers were of the serous histological sub‐type compared to 31% of non‐carriers (Lakhani et al., 2004). Mucinous tumours are rarely observed in BRCA1 mutation carriers (Moslehi et al., 2000; Hirsh‐Yechezkel et al., 2003). There are also significant differences in tumour grade in tumours from BRCA1 carriers compared to non‐carriers; BRCA1 tumours appeared to be more poorly differentiated (Søgaard et al., 2008; Lakhani et al., 2004). Ovarian tumours from mutation carriers may also be diagnosed at a later stage (Søgaard et al., 2008).

There appears to be some indication that BRCA1 carriers have a better survival than non‐carriers. The same may also be true for BRCA2 carriers. In a review of 12 studies, 6 showed significantly better survival in carriers and 4 showed an advantage to carriers, but these were not statistically significant, possibly due to insufficient power due to the small numbers of cases in each study (reviewed Chetrit et al., 2008). The majority of the studies have investigated survival in Ashkenazi Jewish individuals with the 3 founder mutations. Only four of these studies have greater than 40 carriers, and each shows a statistically significant improved survival (Rubin et al., 1996; Boyd et al., 2000; Ben David et al., 2002; Chetrit et al., 2008). The latest study was significant even after adjusting for age, grade and morphology and they found no statistical difference between the survival of BRCA1 carriers compared to BRCA2 carriers (Chetrit et al., 2008). These studies have an advantage of being a homogeneous group of patients, although it is unclear if the results are applicable to other populations. Most of the remaining studies have evaluated survival in high‐risk families. Some of these studies show improved survival in carriers. However, the largest of these studies did not find a significant difference, although there was a trend towards improved survival in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers compared to non‐carriers (Pharoah et al., 1999). One population‐based study of non‐Ashkenazi Jewish individuals, reported an improved survival in BRCA2 carriers and possibly for BRCA1 carriers, but this was not significant (Pal et al., 2007).

5. Conclusion

The identification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers is important in the clinical management of ovarian cancer in families with breast and/or ovarian cancer. It is one of the few successes of clinical intervention for ovarian cancer in recent years that screening for BRCA1/2 mutations is now offered routinely in clinical practice. Currently, only women with a significant family history of ovarian and/or breast cancer are offered genetic testing. If a mutation is found in an unaffected woman, she can be offered the intervention of prophylactic surgery and/or more intense screening to detect the earliest, treatable signs of the disease. For women who are negative for a known mutation in their family, there is a level of reassurance that they are not at the highest risk of developing ovarian or breast cancer. The effectiveness of these intervention strategies in the prevention of both breast and ovarian cancer in carriers has been reviewed previously (Bermejo‐Pérez et al., 2007). The one caveat to genetic testing is that BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations are relatively rare and account for only a small proportion of the total ovarian cancer burden. In addition, testing is not population based. In the UK, The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines suggest genetic testing should be given when there is a 20% chance of having a deleterious mutation in the family. Several programs have been developed that enable accurate predictions of disease and the likelihood that a BRCA1/2 mutation is present, based on a family history. The most commonly used risk prediction packages are BOADICEA, BRCAPRO, IBIS, Myriad and the Manchester scoring method (reviewed Evans and Howell, 2007; Culver et al., 2006). Of these, the BOADICEA model appears to perform the best (Antoniou et al., 2008). The hope for the future is that genetic testing will become more accurate, faster and less expensive, because the more women that can be screened for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, the greater number of lives that will be saved. The identification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 may also be leading to the development of personalised therapies for ovarian cancer. Recently it has been shown that PARP inhibitors are effective in reducing the tumour burden in patients that are BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 null (reviewed Lord and Ashworth, 2008; Drew and Calvert, 2008). These studies are currently in phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials and it is hoped that therapeutic strategies based on PARP inhibition will be an effective treatment for any ovarian (and breast) cancer that shows loss of BRCA1/2, whether they be familial or sporadic tumours.

Ramus Susan J., Gayther Simon A., (2009), The Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 to Ovarian Cancer, Molecular Oncology, 3, doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.02.001.

References

- Anton-Culver, H. , Cohen, P.F. , Gildea, M.E. , Ziogas, A. , 2000. Characteristics of BRCA1 mutations in a population-based case series of breast and ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 36, 1200–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, A.C. , Pharoah, P.D. , McMullan, G. , Day, N.E. , Stratton, M.R. , Peto, J. , Ponder, B.J. , Easton, D.F. , 2002. A comprehensive model for familial breast cancer incorporating BRCA1, BRCA2 and other genes. Br. J. Cancer. 86, 76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, A. , Pharoah, P.D. , Narod, S. , Risch, H.A. , Eyfjord, J.E. , Hopper, J.L. , Loman, N. , Olsson, H. , Johannsson, O. , Borg, A. , 2003. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet.. 72, 1117–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, A.C. , Pharoah, P.D. , Narod, S. , Risch, H.A. , Eyfjord, J.E. , Hopper, J.L. , Olsson, H. , Johannsson, O. , Borg, A. , Pasini, B. , 2005. Breast and ovarian cancer risks to carriers of the BRCA1 5382insC and 185delAG and BRCA2 6174delT mutations: a combined analysis of 22 population based studies. J. Med. Genet.. 42, 602–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, A.C. , Hardy, R. , Walker, L. , Evans, D.G. , Shenton, A. , Eeles, R. , Shanley, S. , Pichert, G. , Izatt, L. , Rose, S. , 2008. Predicting the likelihood of carrying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: validation of BOADICEA, BRCAPRO, IBIS, Myriad and the Manchester scoring system using data from UK genetics clinics. J. Med. Genet.. 45, 425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben David, Y. , Chetrit, A. , Hirsh-Yechezkel, G. , Friedman, E. , Beck, B.D. , Beller, U. , Ben-Baruch, G. , Fishman, A. , Levavi, H. , Lubin, F. , National Israeli Study of Ovarian Cancer, 2002. Effect of BRCA mutations on the length of survival in epithelial ovarian tumors. J. Clin. Oncol.. 20, 463–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchuck, A. , Heron, K.A. , Carney, M.E. , Lancaster, J.M. , Fraser, E.G. , Vinson, V.L. , Deffenbaugh, A.M. , Miron, A. , Marks, J.R. , Futreal, P.A. , 1998. Frequency of germline and somatic BRCA1 mutations in ovarian cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.. 4, 2433–2437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, A. , Flodin, A. , Engwall, Y. , Arkblad, E.L. , Berg, K. , Einbeigi, Z. , Martinsson, T. , Wahlström, J. , Karlsson, P. , Nordling, M. , 2005. A high frequency of germline BRCA1/2 mutations in western Sweden detected with complementary screening techniques. Fam. Cancer.. 4, 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergthorsson, J.T. , Ejlertsen, B. , Olsen, J.H. , Borg, A. , Nielsen, K.V. , Barkardottir, R.B. , Klausen, S. , Mouridsen, H.T. , Winther, K. , Fenger, K. , 2001. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation status and cancer family history of Danish women affected with multifocal or bilateral breast cancer at a young age. J. Med. Genet.. 38, 361–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermejo-Pérez, M.J. , Márquez-Calderón, S. , Llanos-Méndez, A. , 2007. Effectiveness of preventive interventions in BRCA1/2 gene mutation carriers: a systematic review. Int. J. Cancer. 121, 225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørge, T. , Lie, A.K. , Hovig, E. , Gislefoss, R.E. , Hansen, S. , Jellum, E. , Langseth, H. , Nustad, K. , Tropé, C.G. , Dørum, A. , 2004. BRCA1 mutations in ovarian cancer and borderline tumours in Norway: a nested case-control study. Br. J. Cancer. 91, 1829–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, J. , Sonoda, Y. , Federici, M.G. , Bogomolniy, F. , Rhei, E. , Maresco, D.L. , Saigo, P.E. , Almadrones, L.A. , Barakat, R.R. , Brown, C.L. , 2000. Clinicopathologic features of BRCA-linked and sporadic ovarian cancer. JAMA. 283, 2260–2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bork, P. , Hofmann, K. , Bucher, P. , Neuwald, A.F. , Altschul, S.F. , Koonin, E.V. , 1997. A superfamily of conserved domains in DNA damage-responsive cell cycle checkpoint proteins. FASEB J.. 11, 68–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. , Parmigiani, G. , 2007. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J. Clin. Oncol.. 25, 1329–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenevix-Trench, G. , Milne, R.L. , Antoniou, A.C. , Couch, F.J. , Easton, D.F. , Goldgar, D.E. , CIMBA, 2007. An international initiative to identify genetic modifiers of cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (CIMBA). Breast Cancer Res.. 9, 104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetrit, A. , Hirsh-Yechezkel, G. , Ben-David, Y. , Lubin, F. , Friedman, E. , Sadetzki, S. , 2008. Effect of BRCA1/2 mutations on long-term survival of patients with invasive ovarian cancer: the national Israeli study of ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.. 26, 20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, N. , McManus, R. , Wooster, R. , Mangion, J. , Seal, S. , Lakhani, S.R. , Ormiston, W. , Daly, P.A. , Ford, D. , Easton, D.F. , 1995. Consistent loss of the wild type allele in breast cancers from a family linked to the BRCA2 gene on chromosome 13q12-13. Oncogene. 10, 1673–1675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver, J. , Lowstuter, K. , Bowling, L. , 2006. Assessing breast cancer risk and BRCA1/2 carrier probability. Breast Dis.. 27, 5–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez, O. , Osorio, A. , Durán, M. , Martinez-Ferrandis, J.I. , de, la Hoya, M. , Salazar, R. , Vega, A. , Campos, B. , Rodríguez-López, R. , Velasco, E. , 2003. Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in Spanish breast/ovarian cancer patients: a high proportion of mutations unique to Spain and evidence of founder effects. Hum. Mutat.. 22, 301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dørum, A. , Hovig, E. , Tropé, C. , Inganas, M. , Møller, P. , 1999. Three percent of Norwegian ovarian cancers are caused by BRCA1 1675delA or 1135insA. Eur. J. Cancer. 35, 779–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew, Y. , Calvert, H. , 2008. The potential of PARP inhibitors in genetic breast and ovarian cancers. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci.. 1138, 136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D.F. , Pooley, K.A. , Dunning, A.M. , Pharoah, P.D. , Thompson, D. , Ballinger, D.G. , Struewing, J.P. , Morrison, J. , Field, H. , Luben, R. , 2007. Genome-wide association study identifies novel breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nature. 447, 1087–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeles, R.A. , Kote-Jarai, Z. , Giles, G.G. , Olama, A.A. , Guy, M. , Jugurnauth, S.K. , Mulholland, S. , Leongamornlert, D.A. , Edwards, S.M. , Morrison, J. , 2008. Multiple newly identified loci associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat. Genet.. 40, 316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einbeigi, Z. , Bergman, A. , Meis-Kindblom, J.M. , Flodin, A. , Bjursell, C. , Martinsson, T. , Kindblom, L.G. , Wahlström, J. , Wallgren, A. , Nordling, M. , 2007. Occurrence of both breast and ovarian cancer in a woman is a marker for the BRCA gene mutations: a population-based study from western Sweden. Fam. Cancer. 6, 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmasry, K. , Gayther, S.A. , 2007. Epidemiology of ovarian cancer. In Reznek R., Cancer of the Ovary. Cambridge University Press; UK: 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.G. , Howell, A. , 2007. Breast cancer risk-assessment models. Breast Cancer Res.. 9, 213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.G. , Young, K. , Bulman, M. , Shenton, A. , Wallace, A. , Lalloo, F. , 2008. Probability of BRCA1/2 mutation varies with ovarian histology: results from screening 442 ovarian cancer families. Clin. Genet.. 73, 338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferla, R. , Calò, V. , Cascio, S. , Rinaldi, G. , Badalamenti, G. , Carreca, I. , Surmacz, E. , Colucci, G. , Bazan, V. , Russo, A. , 2007. Founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Ann. Oncol.. 18, (Suppl. 6) vi93–vi98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, D. , Easton, D.F. , Stratton, M. , Narod, S. , Goldgar, D. , Devilee, P. , Bishop, D.T. , Weber, B. , Lenoir, G. , Chang-Claude, J. , the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium, 1998. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am. J. Hum. Genet.. 62, 676–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, T.S. , Deffenbaugh, A.M. , Reid, J.E. , Hulick, M. , Ward, B.E. , Lingenfelter, B. , Gumpper, K.L. , Scholl, T. , Tavtigian, S.V. , Pruss, D.R. , 2002. Clinical characteristics of individuals with germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: analysis of 10,000 individuals. J. Clin. Oncol.. 20, 1480–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenson, B. , 2005. BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathways and the risk of cancers other than breast or ovarian. MedGenMed. 7, 60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayther, S.A. , Warren, W. , Mazoyer, S. , Russell, P.A. , Harrington, P.A. , Chiano, M. , Seal, S. , Hamoudi, R. , van Rensburg, E.J. , Dunning, A.M. , 1995. Germline mutations of the BRCA1 gene in breast and ovarian cancer families provide evidence for a genotype-phenotype correlation. Nat. Genet.. 11, 428–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayther, S.A. , Mangion, J. , Russell, P. , Seal, S. , Barfoot, R. , Ponder, B.A. , Stratton, M.R. , Easton, D. , 1997. Variation of risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with different germline mutations of the BRCA2 gene. Nat. Genet.. 15, 103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayther, S.A. , Russell, P. , Harrington, P. , Antoniou, A.C. , Easton, D.F. , Ponder, B.A. , 1999. The contribution of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to familial ovarian cancer: no evidence for other ovarian cancer-susceptibility genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet.. 65, 1021–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsdottir, K. , Ashworth, A. , 2006. The roles of BRCA1 and BRCA2 and associated proteins in the maintenance of genomic stability. Oncogene. 25, 5864–5874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson, J. , Sulem, P. , Rafnar, T. , Bergthorsson, J.T. , Manolescu, A. , Gudbjartsson, D. , Agnarsson, B.A. , Sigurdsson, A. , Benediktsdottir, K.R. , Blondal, T. , 2008. Common sequence variants on 2p15 and Xp11.22 confer susceptibility to prostate cancer. Nat. Genet.. 40, 281–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Górski, B. , Menkiszak, J. , Gronwald, J. , Lubinski, J. , Narod, S.A. , 2004. A protein truncating BRCA1 allele with a low penetrance of breast cancer. J. Med. Genet.. 41, e130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Górski, B. , Jakubowska, A. , Huzarski, T. , Byrski, T. , Gronwald, J. , Grzybowska, E. , Mackiewicz, A. , Stawicka, M. , Bebenek, M. , Sorokin, D. , 2004. A high proportion of founder BRCA1 mutations in Polish breast cancer families. Int. J. Cancer. 110, 683–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes, A.M. , Cruger, D.G. , Thomassen, M. , Kruse, T.A. , 2006. Evaluation of two different models to predict BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a cohort of Danish hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer families. Clin. Genet.. 69, 171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginolhac, S.M. , Gad, S. , Corbex, M. , Bressac-De-Paillerets, B. , Chompret, A. , Bignon, Y.J. , Peyrat, J.P. , Fournier, J. , Lasset, C. , Giraud, S. , 2003. BRCA1 wild-type allele modifies risk of ovarian cancer in carriers of BRCA1 germ-line mutations. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.. 12, 90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh-Yechezkel, G. , Chetrit, A. , Lubin, F. , Friedman, E. , Peretz, T. , Gershoni, R. , Rizel, S. , Struewing, J.P. , Modan, B. , 2003. Population attributes affecting the prevalence of BRCA mutation carriers in epithelial ovarian cancer cases in Israel. Gynecol. Oncol.. 89, 494–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D.J. , Ginolhac, S.M. , Coupier, I. , Corbex, M. , Bressac-de-Paillerets, B. , Chompret, A. , Bignon, Y.J. , Uhrhammer, N. , Lasset, C. , Giraud, S. , 2005. Common BRCA2 variants and modification of breast and ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.. 14, 265–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, D.J. , Kraft, P. , Jacobs, K.B. , Cox, D.G. , Yeager, M. , Hankinson, S.E. , Wacholder, S. , Wang, Z. , Welch, R. , Hutchinson, A. , 2007. A genome-wide association study identifies alleles in FGFR2 associated with risk of sporadic postmenopausal breast cancer. Nat. Genet.. 39, 870–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesdottir, G. , Gudmundsson, J. , Bergthorsson, J.T. , Arason, A. , Agnarsson, B.A. , Eiriksdottir, G. , Johannsson, O.T. , Borg, A. , Ingvarsson, S. , Easton, D.F. , 1996. High prevalence of the 999del5 mutation in icelandic breast and ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Res.. 56, 3663–3665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani, S.R. , Manek, S. , Penault-Llorca, F. , Flanagan, A. , Arnout, L. , Merrett, S. , McGuffog, L. , Steele, D. , Devilee, P. , Klijn, J.G. , 2004. Pathology of ovarian cancers in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Clin. Cancer Res.. 10, 2473–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liede, A. , Malik, I.A. , Aziz, Z. , Rios Pd Pde, L. , Kwan, E. , Narod, S.A. , 2002. Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to breast and ovarian cancer in Pakistan. Am. J. Hum. Genet.. 71, 595–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C.J. , Ashworth, A. , 2008. Targeted therapy for cancer using PARP inhibitors. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol.. 8, 363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubinski, J. , Phelan, C.M. , Ghadirian, P. , Lynch, H.T. , Garber, J. , Weber, B. , Tung, N. , Horsman, D. , Isaacs, C. , Monteiro, A.N. , 2004. Cancer variation associated with the position of the mutation in the BRCA2 gene. Fam. Cancer. 3, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, J.R. , Risch, H.A. , Lubinski, J. , Moller, P. , Ghadirian, P. , Lynch, H. , Karlan, B. , Fishman, D. , Rosen, B. , Neuhausen, S.L. , 2007. Hereditary Ovarian Cancer Clinical Study Group. Reproductive risk factors for ovarian cancer in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations: a case-control study. Lancet Oncol.. 8, 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malander, S. , Ridderheim, M. , Måsbäck, A. , Loman, N. , Kristoffersson, U. , Olsson, H. , Nilbert, M. , Borg, A. , 2004. One in 10 ovarian cancer patients carry germ line BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations: results of a prospective study in Southern Sweden. Eur. J. Cancer. 40, 422–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, G.J. , Thorne, H. , Balleine, R.L. , Butow, P.N. , Clarke, C.L. , Edkins, E. , Evans, G.M. , Fereday, S. , Haan, E. , Gattas, M. , 2006. Kathleen Cuningham Consortium for Research in Familial Breast Cancer Analysis of cancer risk and BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence in the kConFab familial breast cancer resource. Breast Cancer Res.. 8, R12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima, M. , Kobayashi, K. , Emi, M. , Saito, H. , Saito, J. , Suzumori, K. , Nakamura, Y. , 1995. Mutation analysis of the BRCA1 gene in 76 Japanese ovarian cancer patients: four germline mutations, but no evidence of somatic mutation. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 4, 1953–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazoyer, S. , 2005. Genomic rearrangements in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Hum. Mutat.. 25, 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meindl, A. , German Consortium for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer, 2002. Comprehensive analysis of 989 patients with breast or ovarian cancer provides BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation profiles and frequencies for the German population. Int. J. Cancer. 97, 472–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menkiszak, J. , Gronwald, J. , Górski, B. , Jakubowska, A. , Huzarski, T. , Byrski, T. , Foszczyńska-Kłoda, M. , Haus, O. , Janiszewska, H. , Perkowska, M. , 2003. Hereditary ovarian cancer in Poland. Int. J. Cancer. 106, 942–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, P. , Voigtlaender, T. , Bartram, C.R. , Klaes, R. , 2003. Twenty-three novel BRCA1 and BRCA2 sequence alterations in breast and/or ovarian cancer families in Southern Germany. Hum. Mutat.. 22, 259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki, Y. , Swensen, J. , Shattuck-Eidens, D. , Futreal, P.A. , Harshman, K. , Tavtigian, S. , Liu, Q. , Cochran, C. , Bennett, L.M. , Ding, W. , 1994. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 . Science. 266, 66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modan, B. , Hartge, P. , Hirsh-Yechezkel, G. , Chetrit, A. , Lubin, F. , Beller, U. , Ben-Baruch, G. , Fishman, A. , Menczer, J. , Ebbers, S.M. , National Israel Ovarian Cancer Study Group, 2001. Parity, oral contraceptives, and the risk of ovarian cancer among carriers and noncarriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moslehi, R. , Chu, W. , Karlan, B. , Fishman, D. , Risch, H. , Fields, A. , Smotkin, D. , Ben-David, Y. , Rosenblatt, J. , Russo, D. , 2000. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation analysis of 208 Ashkenazi Jewish women with ovarian cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet.. 66, 1259–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhausen, S.L. , Godwin, A.K. , Gershoni-Baruch, R. , Schubert, E. , Garber, J. , Stoppa-Lyonnet, D. , Olah, E. , Csokay, B. , Serova, O. , Lalloo, F. , 1998. Haplotype and phenotype analysis of nine recurrent BRCA2 mutations in 111 families: results of an international study. Am. J. Hum. Genet.. 62, 1381–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal, T. , Permuth-Wey, J. , Betts, J.A. , Krischer, J.P. , Fiorica, J. , Arango, H. , LaPolla, J. , Hoffman, M. , Martino, M.A. , Wakeley, K. , 2005. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for a large proportion of ovarian carcinoma cases. Cancer. 104, 2807–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal, T. , Permuth-Wey, J. , Kapoor, R. , Cantor, A. , Sutphen, R. , 2007. Improved survival in BRCA2 carriers with ovarian cancer. Fam. Cancer. 6, 113–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin-Vidoz, L. , Sinilnikova, O.M. , Stoppa-Lyonnet, D. , Lenoir, G.M. , Mazoyer, S. , 2002. The nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway triggers degradation of most BRCA1 mRNAs bearing premature termination codons. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 11, 2805–2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrij-Bosch, A. , Peelen, T. , vanVliet, M. , vanEijk, R. , Olmer, R. , Drusedau, M. , Hogervorst, F.B. , Hageman, S. , Arts, P.J. , Ligtenberg, M.J. , 1997. BRCA1 genomic deletions are major founder mutations in Dutch breast cancer patients. Nat. Genet.. 17, 341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharoah, P.D.P. , Easton, D.F. , Stockton, D.L. , Gayther, S.A. , Ponder, B.A.J. , 1999. Survival in familial, BRCA1 and BRCA2 associated epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res.. 59, 868–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharoah, P.D. , Antoniou, A. , Bobrow, M. , Zimmern, R.L. , Easton, D.F. , Ponder, B.A. , 2002. Polygenic susceptibility to breast cancer and implications for prevention. Nat. Genet.. 31, 33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, C.M. , Kwan, E. , Jack, E. , Li, S. , Morgan, C. , Aubé, J. , Hanna, D. , Narod, S.A. , 2002. A low frequency of non-founder BRCA1 mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish breast–ovarian cancer families. Hum. Mutat.. 20, 352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlreich, P. , Zikan, M. , Stribrna, J. , Kleibl, Z. , Janatova, M. , Kotlas, J. , Zidovska, J. , Novotny, J. , Petruzelka, L. , Szabo, C. , 2005. High proportion of recurrent germline mutations in the BRCA1 gene in breast and ovarian cancer patients from the Prague area. Breast Cancer Res.. 7, R728–R736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puget, N. , Sinilnikova, O.M. , Stoppa-Lyonnet, D. , Audoynaud, C. , Pages, S. , Lynch, H.T. , Goldgar, D. , Lenoir, G.M. , Mazoyer, S. , 1999. An Alu-mediated 6-kb duplication in the BRCA1 gene: a new founder mutation?. Am. J. Hum. Genet.. 64, 300–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafnar, T. , Benediktsdottir, K.R. , Eldon, B.J. , Gestsson, T. , Saemundsson, H. , Olafsson, K. , Salvarsdottir, A. , Steingrimsson, E. , Thorlacius, S. , 2004. BRCA2, but not BRCA1, mutations account for familial ovarian cancer in Iceland: a population-based study. Eur. J. Cancer. 40, 2788–2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramus, S.J. , Fishman, A. , Pharoah, P.D. , Yarkoni, S. , Altaras, M. , Ponder, B.A. , 2001. Ovarian cancer survival in Ashkenazi Jewish patients with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol.. 27, 278–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramus, S.J. , Harrington, P. , Pye, C. , DiCioccio, R. , Cox, M. , Garlinghouse-Jones, K. , Oakley-Girvan, I. , Jacobs, I.J. , Hardy, R.M. , Whittemore, A. , 2007. The contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to inherited ovarian cancer. Hum. Mutat.. 28, 1207–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, W.E. , Gallion, H.H. , Schmittschmitt, J.P. , Holladay, D.V. , Smith, S.A. , 1999. BRCA1-related and sporadic ovarian cancer in the same family: implications for genetic testing. Gynecol. Oncol.. 75, 468–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch, H.A. , McLaughlin, J.R. , Cole, D.E. , Rosen, B. , Bradley, L. , Fan, I. , Tang, J. , Li, S. , Zhang, S. , Shaw, P.A. , 2001. Population BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies and cancer penetrances: a kin-cohort study in Ontario. Canada. J. Natl. Cancer Inst.. 98, 1694–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch, H.A. , McLaughlin, J.R. , Cole, D.E. , Rosen, B. , Bradley, L. , Kwan, E. , Jack, E. , Vesprini, D.J. , Kuperstein, G. , Abrahamson, J.L. , 2001. Prevalence and penetrance of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population series of 649 women with ovarian cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet.. 68, 700–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, S.C. , Benjamin, I. , Behbakht, K. , Takahashi, H. , Morgan, M.A. , LiVolsi, V.A. , Berchuck, A. , Muto, M.G. , Garber, J.E. , Weber, B.L. , 1996. Clinical and pathological features of ovarian cancer in women with germ-line mutations of BRCA1 . N. Engl. J. Med.. 335, 1413–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, S.C. , Blackwood, M.A. , Bandera, C. , Behbakht, K. , Benjamin, I. , Rebbeck, T.R. , Boyd, J. , 1998. BRCA1, BRCA2, and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer gene mutations in an unselected ovarian cancer population: relationship to family history and implications for genetic testing. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.. 178, 670–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satagopan, J.M. , Boyd, J. , Kauff, N.D. , Robson, M. , Scheuer, L. , Narod, S. , Offit, K. , 2002. Ovarian cancer risk in Ashkenazi Jewish carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Clin. Cancer Res.. 8, 3776–3781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarantaus, L. , Vahteristo, P. , Bloom, E. , Tamminen, A. , Unkila-Kallio, L. , Butzow, R. , Nevanlinna, H. , 2001. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among 233 unselected Finnish ovarian carcinoma patients. Eur. J. Hum. Genet.. 9, 424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully, R. , Chen, J. , Plug, A. , Xiao, Y. , Weaver, D. , Feunteun, J. , Ashley, T. , Livingston, D.M. , 1997. Association of BRCA1 with Rad51 in mitotic and meiotic cells. Cell. 88, 265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinilnikova, O.M. , Mazoyer, S. , Bonnardel, C. , Lynch, H.T. , Narod, S.A. , Lenoir, G.M. , 2006. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast and ovarian cancer syndrome: reflection on the Creighton University historical series of high risk families. Fam. Cancer. 5, 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.A. , Easton, D.F. , Evans, D.G. , Ponder, B.A. , 1992. Allele losses in the region 17q12-21 in familial breast and ovarian cancer involve the wild-type chromosome. Nat. Genet.. 2, 128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.A. , Richards, W.E. , Caito, K. , Hanjani, P. , Markman, M. , DeGeest, K. , Gallion, H.H. , 2001. BRCA1 germline mutations and polymorphisms in a clinic-based series of ovarian cancer cases: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol. Oncol.. 83, 586–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Søgaard, M. , KrugerKjaer, S. , Cox, M. , Wozniak, E. , Hogdall, E. , Hogdall, C. , Blaeker, J. , Jacobs, I.J. , Gayther, S.A. , Ramus, S.J. , 2008. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence and clinical characteristics in an ovarian cancer case population from Denmark clin. Cancer Res.. 14, 3761–3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolenko, A.P. , Rozanov, M.E. , Mitiushkina, N.V. , Sherina, N.Y. , Iyevleva, A.G. , Chekmariova, E.V. , Buslov, K.G. , Shilov, E.S. , Togo, A.V. , Bit-Sava, E.M. , 2007. Founder mutations in early-onset, familial and bilateral breast cancer patients from Russia. Fam. Cancer. 6, 281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, J.F. , Pharoah, P.D.P. , Smith, S.K. , Easton, D.F. , Ponder, B.A.J. , 1998. A systematic review and meta- analysis of family history and risk of ovarian cancer. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol.. 105, 493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, J.F. , Gayther, S.A. , Russell, P. , Dearden, J. , Gore, M. , Blake, P. , Easton, D. , Ponder, B.A. , 1997. Contribution of BRCA1 mutations to ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.. 336, 1125–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, H. , Behbakht, K. , McGovern, P.E. , Chiu, H.C. , Couch, F.J. , Weber, B.L. , Friedman, L.S. , King, M.C. , Furusato, M. , LiVolsi, V.A. , 1995. Mutation analysis of the BRCA1 gene in ovarian cancers. Cancer Res.. 55, 2998–3002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, H. , Chiu, H.C. , Bandera, C.A. , Behbakht, K. , Liu, P.C. , Couch, F.J. , Weber, B.L. , LiVolsi, V.A. , Furusato, M. , Rebane, B.A. , 1996. Mutations of the BRCA2 gene in ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res.. 56, 2738–2741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenesa, A. , Farrington, S.M. , Prendergast, J.G. , Porteous, M.E. , Walker, M. , Haq, N. , Barnetson, R.A. , Theodoratou, E. , Cetnarskyj, R. , Cartwright, N. , 2008. Genome-wide association scan identifies a colorectal cancer susceptibility locus on 11q23 and replicates risk loci at 8q24 and 18q21. Nat. Genet.. 40, 631–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The BRCA1 Exon 13 Duplication Screening Group, 2000. The exon 13 duplication in the BRCA1 gene is a founder mutation present in geographically diverse populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet.. 67, 207–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium, 1999. Cancer Risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst.. 91, 1310–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D. , Easton, D. , the BCLC, 2001. Variation in cancer risks, by mutation position, in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Am. J. Hum. Genet.. 68, 410–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D. , Easton, D. , Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium, 2002. Variation in BRCA1 cancer risks by mutation position. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.. 11, 329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D. , Easton, D.F. , the BCLC, 2002. Cancer incidence in BRCA1 mutations carriers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst.. 94, 1358–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, I.P. , Webb, E. , Carvajal-Carmona, L. , Broderick, P. , Howarth, K. , Pittman, A.M. , Spain, S. , Lubbe, S. , Walther, A. , Sullivan, K. , 2008. A genome-wide association study identifies colorectal cancer susceptibility loci on chromosomes 10p14 and 8q23.3. Nat. Genet.. 40, 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonin, P.N. , Mes-Masson, A.M. , Narod, S.A. , Ghadirian, P. , Provencher, D. , 1999. Founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in French Canadian ovarian cancer cases unselected for family history. Clin. Genet.. 55, 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Looij, M. , Szabo, C. , Besznyak, I. , Liszka, G. , Csokay, B. , Pulay, T. , Toth, J. , Devilee, P. , King, M.C. , Olah, E. , 2000. Prevalence of founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among breast and ovarian cancer patients in Hungary. Int. J.Cancer. 86, 737–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoog, L.C. , van, den , Ouweland, A.M. , Berns, E. , vanVeghel-Plandsoen, M.M. , vanStaveren, I.L. , Wagner, A. , Bartels, C.C. , Tilanus-Linthorst, M.M. , Devilee, P. , Seynaeve, C. , 2001. Large regional differences in the frequency of distinct BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in 517 Dutch breast and/or ovarian cancer families. Eur. J. Cancer. 37, 2082–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware, M.D. , DeSilva, D. , Sinilnikova, O.M. , Stoppa-Lyonnet, D. , Tavtigian, S.V. , Mazoyer, S. , 2006. Does nonsense-mediated mRNA decay explain the ovarian cancer cluster region of the BRCA2 gene?. Oncogene. 25, 323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooster, R. , Bignell, G. , Lancaster, J. , Swift, S. , Seal, S. , Mangion, J. , Collins, N. , Gregory, S. , Gumbs, C. , Micklem, G. , 1995. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2 . Nature. 378, 789–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore, A.S. , Harris, R. , Itnyre, J. , 1992. Characteristics relating to ovarian cancer risk: collaborative analysis of 12 US case-control studies. IV. The pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer. Collaborative Ovarian Cancer Group. Am. J. Epidemiol.. 136, 1212–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore, A.S. , Balise, R.R. , Pharoah, P.D. , Dicioccio, R.A. , Oakley-Girvan, I. , Ramus, S.J. , Daly, M. , Usinowicz, M.B. , Garlinghouse-Jones, K. , Ponder, B.A. , 2004. Oral contraceptive use and ovarian cancer risk among carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutations. Br. J. Cancer. 91, 1911–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazici, H. , Glendon, G. , Yazici, H. , Burnie, S.J. , Saip, P. , Buyru, F. , Bengisu, E. , Andrulis, I.L. , Dalay, N. , Ozcelik, H. , 2002. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Turkish familial and non-familial ovarian cancer patients: a high incidence of mutations in non-familial cases. Hum. Mutat.. 20, 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, K. , Miki, Y. , 2004. Role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 as regulators of DNA repair, transcription, and cell cycle in response to DNA damage. Cancer Sci.. 95, 866–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]