Abstract

The role of acquired chromosomal rearrangements in oncogenesis (cytogenomics) and tumor progression is now well established. These alterations are multiple and diverse and the products of these rearranged genes play an essential role in the transformation and growth of cancer cells. The validity of this assumption is demonstrated by the development of specific inhibitors or antibodies that eliminate tumoral cells by targeting some of these changes. Imatinib, an inhibitor of the tyrosine kinase ABL, the prototype of these targeting drugs, is yielding complete remissions in most CML patients. Knowledge of chromosomal abnormalities is becoming an essential contribution to the diagnosis and prognosis of cancers but also for monitoring minimal residual disease or relapse. The concept of the “cytogenetic uniqueness” of each cancer has resulted in personalized treatment. This investigation will expound upon, besides the recurrent genomic alterations, the numerous products of perverted Darwinian selection at the cellular level.

Keywords: Cancer, Chromosome abnormalities, Cytogenetics, Oncogenesis

1. Introduction

The Boveri hypothesis (Boveri, 1914) that cancer could be a chromosomal disease (Balmain, 2001) of the cell genome has been widely demonstrated by the cytogenetics and genomics of malignant diseases during the last fifty years. The seminal observations of the Ph chromosome in CML (Nowell and Hungerford, 1960; Rowley, 1973) and the correlation between double minute chromosomes and genetic amplification are examples of how fruitful this approach has been. Acquired and monoclonal characteristics of most malignancies and the clonal evolution of tumor cell populations were described by cytogeneticists before the era of chromosome banding. Specific chromosomal rearrangements, mainly translocations were described by banding and were found to be malignancy‐specific (hematological or mesenchymal malignancies). Due to their presence in various cell types in bone marrow, they allowed us to demonstrate the coexistence of normal and malignant cells in the same tissue and led to the hypothesis of stem cell involvement in several malignancies (e.g. MDS or CML). Using the Ph chromosome as a marker of malignant cells, it was possible to show that it was present in all myeloid cells including B lymphocytes (Bernheim et al., 1981b).

The recurrent breakpoints found in translocations in leukemia and lymphoma were enigmatic when gene mapping was in its infancy. The observation of variant translocations in Burkitt's lymphoma allowed us to hypothesize that the specific breakpoint of this proliferation was located on 8q24 (Bernheim et al., 1981a), near a “transforming gene” (Lenoir et al., 1981), because the term “oncogene” was too precise to be used at the time. The correlation between the localization of the immunoglobulin genes on chromosomes 14, 2 or 22 and the 8q24 factor allowed us to put forward the hypothesis of a position effect due to the translocation of a promoter from the immunoglobulin gene to a transforming agent (Frohling and Dohner, 2008; Huret, 2010; Lenoir et al., 1982). Cytogenetics, molecular biology and gene mapping paths then converged and the following year enabled the identification of the MYC gene in Burkitt's lymphoma. This MYC gene was dysregulated by an immunoglobulin enhancer of new genes. During the next twenty years, most recurrent balanced breakpoints were cloned (Huret, 2010; Mitelman et al., 2007; Rowley, 1998; Sandberg, 2002), whether they were dysregulated genes such as BCL2 in follicular lymphoma, or chimeric ones. Most of the important genes in malignancies were thus identified. This task continues to be a major issue, as we are well short of exhaustive knowledge of the somatic genetic alterations in malignancy. These results radically changed our view of cancer. The abnormal chromosomes could often be qualified as “markers” of malignancy as they were observed exclusively in malignant cells. Their presence enhanced the quality of the diagnosis and allowed a clearer definition of the prognosis. Several diagnoses have become a routine task. Exquisitely sensitive procedures are used to detect and quantify residual disease. All types and sizes of chromosomal abnormalities can be found in all cancers (Fagin, 2002; Huret et al., 2001; Mitelman et al., 2003). More than 54,000 patients are reported in the Mitelman Catalog (Mitelman et al., 2003) and the WHO (World Health Organization) includes a growing number of genomic rearrangements in the definition of malignancies. More importantly, the products of these mutated or dysregulated genes have become the highly specific targets of new drugs (Druker, 2008; Thompson, 2009) which are radically different from conventional chemotherapy.

2. Origin of chromosomal rearrangements in cancer

The human genome of a cell is far from stable. Chemical alterations, viral aggressions and ionizing radiations are ubiquitous. The process of replication is not absolutely faithful nor is chromosomal segregation at mitosis (even meiosis is not accurate due to gametic malsegregation: more than 60% of zygotes will have a chromosomal abnormality that will lead to an early abortion, which will mostly go unnoticed).

In somatic cells, partial failure is the rule and not the exception. Fresh cells are constantly generated from stem cells and damaged cells are eliminated. Overall control is thus a dynamic process with multiple checkpoints at cellular and organism levels via homeostasis and immunological processes. The actual hypothesis of tumorigenesis is a mutation (including chromosomal rearrangements) (Schvartzman et al., 2010) that confers a selective advantage on a dividing cell. The monoclonal proliferation will be exposed to new mutations with a new round of selection (Gisselsson, 2001). The recursive multi‐stage process will culminate with a significant tumor that will exhibit invasive and metastatic properties and often considerable clinical aggressiveness. This “perverted” Darwinian selection at the cellular level probably acts on larger cell populations than evolution on whole individuals in nature and the time required for the generation process is shorter. However, as tumor development is the exception and generally occurs late in life, the process is poorly efficient and this is also due to very tight controls. Immunology plays a major role, as suggested by the frequency of Burkitt's lymphoma or Kaposi's sarcoma in AIDS patients.

In several benign tumors such as lipoma (Mandahl, 2000) or uterus leiomyoma (Lynch and Morton, 2007) specific clonal chromosomal abnormalities can be observed. This suggests that all genomic rearrangements found in tumors, don't give complete proliferative dysregulation, neither invasive and metastatic characteristics.

Hereditary deficiencies in repair processes such as in Xeroderma Pigmentosum, Fanconi anemia (Moldovan and D'Andrea, 2009) and other chromosomal instability syndromes, often characterized by chromosomal breakages, are characterized by high level malignancies.

Irradiation produces chromosomal breakage as well as mutations and is known to be a potent mutagen. Numerous chemicals are clastogenics including free radicals, of various origins such as a chronic inflammation.

3. Chromosomal rearrangements

Several chromosome rearrangements (Albertson et al., 2003) are very specific and observed only in a particular disease (Mitelman et al., 2003). The translocations found in leukemias, lymphomas, sarcomas and some carcinomas belong to this category (1, 2). They participate in the definition of the disease under the term genetic, as in the recent classifications of the WHO (Swerdlow et al., 2008). Other chromosomal abnormalities simply indicate a cellular malignant process such as isochromosomes 8q and 17q in carcinomas (Huret, 2010) or trisomy 8 in acute myeloblastic leukemia (Huret, 2010). The “pattern” is a set of chromosomal abnormalities that have no meaning when isolated, but is more or less associated with the diagnosis. Conventional chromosomal abnormalities are only the tip of the iceberg. Many alterations are too small to be seen by conventional techniques or even because mitosis are lacking, as in most solid tumors.

Table 1.

Selected chromosomal abnormalities in hematological malignancies.

| Disease | Chromosomal abnormalities | Genesa | Type | Targeted therapyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute malignant iymphoid proliferation | ||||

| ALL L1/L2 Pre‐B | t(1;19)(q23;p13) | PBX1‐TCF3 | I | |

| ALL L1/L2 B or biphenotypic | t(9;22)(q34;q11) | ABL‐BCR | I | |

| ALL L1/L2 biphenotypic | t(4;11)(q21;q23) | AF4‐MLL | I | |

| ALL L1/L2 (child) | t(12;21)(p13;q22) | TEL‐AML1 | I | |

| ALL L1/L2 | 50–60 chromosomes, hyper diploidy | III | ||

| ALL L1/L2 | t(5;14)(q31;q32) | IL3*IGH | II | |

| ALL L1/L3 | dup(6)(q22–q23) | MYB | III | |

| ALL L1/L2 | del(9p),t(9p) | ?CDKN2(p16) | IV | |

| ALL L1/L3 | del(9)(p13) | PAX5 | IV | |

| ALL L1/L2 | t(9;12)(q34;p13) | ABL‐TEL | I | |

| ALL L1/L2 | t(11;V)(q23;V) | MLL‐V | I | |

| ALL L1/L2 | del(12p) | ETV6? | IV | |

| ALL L1/L3 | episome(9q34.1)§ | NUP214‐ABL1 | I | Imatinib |

| B (ALL3, Burkitt's leukemia/lymphoma) | t(8;14)(q24;q32) | IGH*MYC | II | |

| B (ALL3, Burkitt's leukemia/lymphoma) | t(2;8)(p12;q24) | IGK*MYCc | II | |

| B (ALL3, Burkitt's leukemia/lymphoma) | t(8;22)(q24;q11) | IGK*MYCc | II | |

| Follicular lymphoma to large‐cell diffuse lymphoma | t(14;18)(q32;q21) and variants | IGH*BCL2/IGK/IGL | II | |

| Mantle‐cell lymphoma | t(11;14)(q13;q32) | CCND1*IGH | II | |

| Marginal zone lymphoma | t(1;14)(p21;q32) | BCL10*IGH | II | |

| Marginal zone lymphoma | 3 | III | ||

| Marginal zone lymphoma | t(11;18)(q21;q21) | BIRC3‐MALT1 | I | |

| Large‐cell diffuse lymphoma | t(3;14)(q27;q32), variants | BCL6*IGH, BCL6*V | II | |

| Large‐cell diffuse lymphoma | t(11;14)(q13;q32) | CCND1*IGH | II | |

| Anaplastic large‐cell lymphoma | t(2;5)(p23;q35), variants | ALK‐NPM1 | I | |

| Chronic malignant lymphoid proliferation | ||||

| Lymphocytic B cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia | t(11;14)(q13;q32) | CCND1*IGH | II | |

| Lymphocytic B cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia | t(14;19)(q32;q13) | IGH*BCL3 | II | |

| Lymphocytic B cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia | t(2;14)(p13;q32) | BCL11A*IGH | II | |

| Lymphocytic B cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia | del(11)(q23.1) | ATM | IV | |

| Lymphocytic B cell lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia | del(13)(q14) | DLEU, miR‐16‐1 & 15a | IV | |

| Prolymphocytic T leukemia | inv(14)(q11q32) | TCRA/TCR D* TCL1A | II | |

| Prolymphocytic T leukemia | t(14;14)(q11;q32) | TCRA/TCR D* TCL1A | II | |

| Prolymphocytic T leukemia | t(7;14)(q35;q32.1) | TCRB* TCL1A | II | |

| Multiple myeloma | t(11;14)(q13;q32) | CCND1*IGH | II | |

| Multiple myeloma | t(4;14)(p16;q32) | WHSC1‐IGHG1 | II | |

| Multiple myeloma | del(6)(q21) | IV | ||

| del(13)(q14) | DLEU, miR‐16‐1 & 15a | IV | ||

| Acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome | ||||

| AML M2 | t(8;21)(q22;q22) | RUNX1‐RUNX1T1 | I | |

| AML M3 and microgranular variant | t(15;17)(q22;q11–12) | PML‐RARA | I | Retinoid Acid |

| AML M3 (atypical) | t(11;17)(q23;q12) | PLZF‐RARA | I | Retinoid Acid |

| AML M4Eo | inv(16)(p13q22) ou | CBFB‐MYH11 | I | |

| t(16;16)(p13;q22 | CBFB‐MYH11 | I | ||

| AML M5a and other AML | t(9;11)(p22;q23) | MLL‐MLLT3 | I | |

| AML M5a and other AML | t(11q23;V) | MLL multiple partners including MLL | I | |

| Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia | t(1;22)(p13;q13) | RBM15‐MKL1 | I | |

| AML, MDS | t(3;3)(q21;q26) or variants | RPN1‐EVI1 | I | |

| AML, MDS | t(3;5)(q25;q34) | MLF1‐NPM1 | I | |

| AML, MDS | t(5;12)(q33;p13) | PDGFRB‐ETV6 | I | |

| AML, MDS | −5/del(5q) | RPS14 | IV | |

| AML, MDS | t(6;9)(p23;q34) | DEK‐NUP214 | I | |

| AML, MDS | t(7;11)(p15;p15) | HOXA9‐NUP98 | I | |

| AML, MDS | −7 ou del(7q) | Numerous genes | IV | |

| AML, MDS | +8 | III | ||

| AML, MDS | t(8;16)(p11;p13) | MOZ‐CBP | I | |

| AML, MDS | t(9;12)(q34; p13) | ETV6‐ABL | I | |

| AML, MDS | t(12;13)(p13;q12.3) | ETV6‐CDX2 | I | |

| AML, MDS | t(12;22)(p13;q13) | ETV6‐NM1 | I | |

| AML, MDS | t(12;V)(p13;V), del(12p) | ETV6L‐V | I | |

| AML, MDS | t(16;21)(p11;q22) | FUS‐ERG | I | |

| AML, MDS | del(20q) | IV | ||

| Therapy‐induced leukemia | ||||

| Alkylating agent‐ and irradiation‐induced leukemia | −5 ou del(5q) | IV | ||

| Alkylating agent‐ and irradiation‐induced leukemia | −7 ou del(7q) | IV | ||

| Anti topoisomerase II induced leukemia | t(11q23;V) | MLL‐V | I | |

| Chronic myeloid proliferation | ||||

| Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) | t(9;22)(q34;q11) | BCR‐ABL1 | I | Imatimib, 2nd generation TKI |

| Lymphoblastic acutisation of CML | t(9;22), +8,+Ph, +19, i(17q) | BCR‐ABL1 | I & III | Imatimib, 2nd generation TKI |

| Polycytemia vera | +9p | III | ||

| Polycytemia vera | del(20q) | IV | ||

| MDS/MPD | t(8;9(p21;p24) | PCM1‐JAK2 | I | |

| Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia | t(5;12)(q33;p13) | PDGFRB‐TEL | I | Imatinib |

| 5q‐ syndrome | del(5q) | RPS14 | IV | |

«*»=dysregulation gene, «‐»=mean fusion gene, V=rearrangement variants. For details see:http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org.

Targeted therapy against genes involved in genetic rearrangements.

miR‐1204 and miR#x2010;1205 could also be dysregulated (Toujani et al., 2009).

Table 2.

Selected examples of chromosomal rearrangements in solid tumors.

| Disease | Chromosomal rearrangements | Geneab | Type | Targeted therapyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | amp(1)(q32.1) | IKBKE | IIIa | |

| Breast and various cancers | amp(6)(q25.1) | ESR1 | IIIa | Tamoxifen |

| Breast cancer | amp(17)(q21.1) | ERBB2 (HER2) | IIIa | Trastuzumab, Lapatinib |

| Breast cancer | amp(20)(q12) | NCOA3 | IIIa | |

| Breast and various cancers | t(12;15)(p13;q25) | ETV6‐NTRK3 | I | |

| Colon cancer | del(4)(q12) | REST | IV | |

| Colon cancer | del(5)(q21–q22) | APC | IV | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | amp(11)(q13–q22) | BIRC2 | IIIa | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | amp(11)(q13–q22) | YAP1 | IIIa | |

| Lung cancer | amp(1)(p34.2) | MYCL1 | IIIa | |

| Lung cancer (non‐small‐cell) | inv(2)(p22–p21p23) | EML4‐ALK | I | |

| Lung, head and neck cancers | amp(3)(q26.3) | DCUN1D1 | IIIa | |

| Lung cancer (non‐small‐cell) | amp(7)(p12) | EGFR | IIIa | Cetuximab, Panitumumab, Gefitinib, Erlotinib |

| Lung cancer (non‐small‐cell) | amp(14)(q13) | NKX2‐1 | IIIa | |

| Ovarian cancer | amp(1)(q22) | RAB25 | IIIa | |

| Ovarian cancer | amp(3)(q26.3) | PIK3CA | IIIa | |

| Ovarian, breast cancers | amp(11)(q13.5) | EMSY | IIIa | |

| Ovarian, breast cancers | amp(17)(q23.1) | RPS6KB1 | IIIa | |

| Prostate cancer | amp(X)(q12) | AR | IIIa | |

| Prostate cancer | del(21)(q22.3q22.3) | TMPRSS2*ERG | II | |

| Renal carcinoma papillary | .+7q31 | MET | ||

| Renal carcinoma papillary | .+7q31 | MET | ||

| Renal carcinoma papillary | .+17q | ? | ||

| Renal carcinoma papillary | .+17q | ? | ||

| Renal carcinoma papillary | t(X;1)(p11;p34) | PSF‐TFE3 | ||

| Renal carcinoma papillary | t(X;1)(p11.2;q21.2) | PRCC‐TFE3 | ||

| Thyroid cancer follicular | t(2;3)(q12–q14;p25) | PAX8‐PPARG | I | |

| Thyroid cancer papillary | inv(10)(q11.2q11.2) | RET‐NCOA4 | I | |

| Thyroid cancer papillary | inv(10)(q11.2q21) | RET‐CCDC6 | I | |

| Ewing's sarcoma | t(11;22)(q24.1–q24.3;q12.2) | FLI1‐EWSR1 | I | |

| Ewing's sarcoma | t(21;22)(q22.3;q12.2) | ERG‐EWSR1 | I | |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma (alveolar) | t(1;13)(p36;q14) | PAX7‐FKHR | I | |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma (alveolar) | t(1;13)(p36;q14) | PAX7‐FKHR | I | |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma (alveolar) | t(2;13)(q37;q14) | PAX3‐FKHR | I | |

| Chondrosarcoma (extrasqueletical) | t(9;17)(q22;q11) | RBP56‐CHN | I | |

| Chondrosarcomas (myxoid) | t(9;22)(q22;q12) | EWS‐CHN | I | |

| Desmoplastic tumors | t(11;22)(p13;q12) | WT1‐EWS | I | |

| Clear cell sarcomas | t(12;22)(q13;q12) | ATF1‐EWS | I | |

| Liposarcomas | t(12;16)(q13;p11) | CHOP‐FUS | I | |

| Liposarcomas (myxoid) | t(12;16)(q13;p11) | CHOP‐FUS | I | |

| Dermatofibrosarcomas protuberans | t(17;22)(q22;q13) | COL1A1‐PDGFB | I | |

| Alveolar soft part sarcomas | der(17)t(X;17)(p11;q25) | ASPSCR1‐TFE3 | I | |

| Synovialosarcomas | t(X;18)(p11.2;q11.2) | SYT‐SSX1/SSX2‐SYT | I | |

| Malignant melanoma | amp(3)(p14.2–p14.1) | MITF | IIIa | |

| Glioma | amp(1)(q32) | MDM4 | IIIa | |

| Astrocytoma, glioblastoma | .+7 | ? | III | |

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma | del(19q) | ? | IV | |

| anaplastic oligodendroglioma | del(1p) | ? | IV | |

| Medulloblastoma | amp(2)(p24.1) | MYCN | IIIa | |

| Medulloblastoma | del(6)(q23.1) | WNT | IV | |

| Medulloblastoma | amp(8)(q24.2) | MYC | IIIa | |

| Medulloblastoma | del(9)(p21) | CDKN2A/CDKN2B | IV | |

| Medulloblastoma | i(17q) | p53 | III, IV | |

| Neuroblastoma | amp(2)(p24.1) | MYCN | IIIa | |

| Neuroblastoma | amp(2)(p23.1) | ALK | IIIa | |

| Neuroblastoma | del(1p) | ? | IV | |

| Renal‐cell cancer | del(3p26–p25) | VHL | IV | |

| Retinoblastoma | del(13)(q14.2) | RB1 | IV | |

| Retinoblastoma | amp(1)(q32) | MDM4 | IIIa | |

| Retinoblastoma | del(13)(q14) | RB | ||

| Testicular germ‐cell tumor | +12p | ? | III | |

| Testicular germ‐cell tumor | +12p | ? | III | |

| Wilms' tumor | del(11p) | WT1 | IV | |

| Wilms' tumor | del(X)(q11.1) | FAM123B | IV | |

| Various cancers | +1q | ? | III | |

| Various cancers | +1q | ? | III | |

| Various cancers | del(3p) | ? | IV | |

| Various cancers | amp(5)(p13) | SKP2 | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | amp(5)(p13) | SKP2 | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | amp(6)(p22) | E2F3 | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | del(6q) | ? | IV | |

| Various cancers | amp(7)(p12) | EGFR | IIIa | Cetuximab, Panitumumab, Gefitinib, Erlotinib |

| Various cancers | amp(7)(q31) | MET | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | amp(8)(p11.2) | FGFR1 | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | amp(8)(q24.2) | MYC | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | del(9)(p21) | CDKN2A/CDKN2B | IV | |

| Various cancers | del(10)(q23.3) | PTEN | IV | |

| Various cancers | amp(11)(q13) | CCND1 | II, IIIa | |

| Various cancers | del(11)(q22–q23) | ATM | IV | |

| Various cancers | del(11q) | ? | IV | |

| Various cancers | amp(12)(p12.1) | KRAS | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | amp(12)(q14.3) | MDM2 | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | amp(12)(q14) | CDK4 | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | amp(12)(q15) | DYRK2 | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | amp(13)(q32) | GPC5 | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | +17q | ? | III | |

| Various cancers | amp(17)(q21.1) | ERBB2 (HER2) | IIIa | Trastuzumab, Lapatinib |

| Various cancers | del(17)(p13.1) | TP53 | IV | |

| Various cancers | del(17)(q11.2) | NF1 | IV | |

| Various cancers | amp(19)(q12) | CCNE1 | IIIa | |

| Various cancers | amp(20)(q13) | AURKA | IIIa |

a«*»=dysregulation gene, «‐»=mean fusion gene, V=rearrangement variants. For details see:http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org.

Often also mutated.

Targeted therapy against genes involved in genetic rearrangements.

4. From cytogenetics to cytogenomics

As the human genome has been completely sequenced, genes along the 46 human chromosomes, which are conventionally known according to their appearance at the fleeting stage of mitosis during metaphase, with two clearly visible chromatids attached to centromeres and capped by a telomere, are now completely mapped. During interphase, the chromosomes are classically indistinct in the cell nucleus. The FISH painting technique has revealed that they maintain their individuality as chromosome territories. The position of the genes in these territories also seems to be important for their expression. A gene is inactive in an internal position, whereas a gene is active at the periphery or outside the territory.

A gene‐rich chromosome such as chromosome 19 seems to fit into an internal position in the nucleus, whereas those lacking in genes are at the nuclear periphery, forming a protection against possible aggression mutagens. It is conceivable that the structural organization of chromosomes in the cell nucleus will become a major subject of study in the near future (Mani et al., 2009; Nikiforova et al., 2000).

The emergence of molecular cytogenetics (Pleasance et al., 2010), whose main methods are in situ hybridization (FISH), comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), and now whole genome sequencing, possibly associated with DNA stretching techniques (DNA combing) and chromosome microdissection, has greatly expanded the cytogenetics field metamorphosing it into cytogenomics (Beroukhim et al., 2010; Bignell et al., 2007).

5. In situ hybridization (ISH)

The molecular reassociation of chromosomal DNA with DNA probes in situ can be done at all stages of the cell cycle. Chemical labeling is now very diverse, allowing the detection of probes by fluorescence or increasingly by cytochemistry. Often available commercially, these reagents cover a continuously growing spectrum of chromosomal rearrangements that are detected on mitotic chromosomes but also on cell nuclei. Consequently, cytogenetic analysis is not limited to successful cell cultures. Adaptations are successfully done on paraffin sections, especially to detect gene amplification such as ERBB2‐NEU, but also for single copy rearrangements. The human genome sequence, available on the Internet, offers tremendous opportunities to cytogeneticists as they can order probes next to a breakpoint, making investigations by FISH available for the entire genome.

The use of three simultaneous florescence stains, one to label each of the two probes and one for DNA staining, is now commonplace. Currently five fluorochromes are typically available to create more than 24 different color combinations simultaneously (SKY, multifish) that identify each chromosome. The fluorescence microscope is now part of a computerized imaging system with automated scanning, ergonomic reading solutions and quality control which is necessary for clinical practice and incorporates these advances.

6. CGH

CGH (Comparative Genomic Hybridization) quantifies test DNA compared to control DNA, and this can be done at any point in the genome. Initially described by Kallioniemi et al. (1992), its principle is simple. The purified tumor DNA is marked by a fluorochrome emitting in green (e.g., fluorescing), whereas normal DNA is marked by another fluorochrome emitting in the red (or vice versa). Originally both DNA were cohybridized on a whole normal human genome, represented by normal human metaphasic chromosomes, according to FISH procedures. The unique chromosome sequences were simultaneously the targets of the tumor and control DNAs. After washing and banding with DAPI to generate banding, preparations were analyzed on a microscopic digital image analyzer. Now the targets are a very large number of BACs or of selected oligonucleotides, sampling the total human genome (Pinkel and Albertson, 2005).

The hybridization of tumor DNA to each point of the genome is compared to that of control DNA. A loss of this region in the tumor genome will be revealed by an excess signal from the normal DNA. Conversely, a gain will be detected by an excess of tumor DNA, which will be major in the case of gene amplification. The exact quantification is done by calculating the normalized ratio between tumor and normal DNA fluorescence along each chromosome. Metaphasic chromosomes are cheap natural microchips covering the entire genome with a high level of integration, but with poor resolution. 1Mb resolution has been achieved with BAC CGH arrays. Now, oligonucleotide chips within the resolution range of a few kb, from 1×105 up to several million, are available and yield robust results.

Paradoxically, CGH greatly simplifies the interpretation of anomalies in its standard format.

Tumor DNA can be prepared from fresh or frozen material. CGH is very sensitive to the presence of normal cells in the sample under analysis, which exert a dilution effect on tumor DNA. This makes CGH unreliable when there are fewer than 60% of normal cells. Enrichment in tumor cells could be done by cell sorting or laser microdissection, but it would probably be difficult to generalize those techniques.

CGH cannot detect balanced translocations and their equivalents, nor overall changes in ploidy (triploidy, tetraploidy). The analysis can be far from simple in some cancers, with the added complexity from inherited CNV. These CNV add complexity to interpretation. However, the simplest way to avoid it is to use normal DNA from each patient as control DNA.

An alternative methodology is single copy number analysis derived from SNP analysis. This approach depicts the loss of heterozygozity (LOH) which occurs via acquired isodisomy, without copy number variation. The incidence reported is about 10% of CNA (copy number aberration). Currently, there is no system allowing the two analyses to be conducted routinely on the same array in cancer.

7. Sequence

Next generation sequencing is rapidly progressing (Mardis, 2009). Prices are dropping every year, making the objective of 1000$, or even less, for a full human genome fully conceivable. Bioinformatics is very demanding but this aspect will be solved in a few years. The first results of whole genome sequencing (WGS) in tumors revealed that the diagnosis of balanced rearrangements could be achieved in the absence of classic karyotypes that require cell culture. Several malignancies have recently been sequenced. Extremely divergent results have been obtained. Several solid tumors exhibit a very high number of mutations, up to more than 20,000, a similar number to that of genes (Pleasance et al., 2010). In contrast, AML, with a normal karyotype, exhibits a few mutations, most of which are in known oncogenes (Mardis et al., 2009).

8. Typology of genomic abnormalities (chromosome and gene) (Table 3)

Table 3.

Chromosome typology abnormalities.

| Abnormality type | Involved genes | Main functional effect | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Fusion genes originating from translocations or other chromosomal rearrangements | Oncogenes, kinases, transcription factors, etc | Function gain | FLI1‐EWS in the t(11;22), MLL duplication |

| Type II | Position effect originating from translocations or other chromosomal rearrangements | Oncogenes, other genes | Dysregulation | IGH*BCL2 in t(14;18), MYC in t(8;14)(q24;q32) |

| Type III | Copy number gain of all or part of a chromosome (IIIs) | Oncogenes, other genes | Gene dosage effect (may act on a modified gene) | Duplication of the Ph in CML, of MET gene by whole trisomy 7 or segmental duplication |

| Type IIIa | Gene amplification (more than 2,2–4 copy per haploid genome | Oncogenes, other genes | Gene dosage effect (sometimes acting on a modified gene) | EGFR in lung cancer, ERBB2/HER2 in breast cancer, MYCN in neuroblastoma |

| Type IV | Total or partial (IVs) loss of a chromosome, Total or partial acquired isodisomy, inactivation by mutation… | Tumor suppressor genes | Loss of function, LOH | Inactivation of RB gene in retinoblastoma via deletion of chromosome 13 or mutation of RB, loss of CDKN2A in various cancers |

Chromosomal abnormalities can be classified into four types, depending on their consequences.

Type I refers to the generally balanced translocations or other structural rearrangements that fuse two genes, forming a hybrid gene. As the structure of eukaryotic genes is divided into exons and introns, this fusion enables the formation of chimeric proteins which acquire an oncogenic potential. This new hybrid gene is malignancy‐specific as for example the FLI1‐EWS fusion gene following the t(11; 22) (q24, q12) translocation in Ewing's sarcoma (Delattre et al., 1992, 1994, 2007) or the EML4‐ALK fusion gene following an inversion on 2p in lung carcinoma (Soda et al., 2007) (1, 2). These anomalies may be regarded as resulting in, strictly speaking, a “gain of function”. The genes involved often involve transcription factors but also tyrosine kinases. These often balanced abnormalities first appeared to be mainly confined to hematological malignancies and sarcomas but they are now often found in carcinomas. Anomalies of RET or of the PAX8‐PPARG fusion gene in thyroid cancer (Nikiforova and Nikiforov, 2009; Pierotti, 2001), the t(X;1) translocation in cancers of the kidney (Argani et al., 2003; Camparo et al., 2008), the inv(2)(p21p23) fusing EML4 to ALK in lung cancers are good examples (Table 3). Cryptic genomic rearrangements may contribute to gain of function: partial duplication of a gene on itself as in MLL with the 5′ part is sometimes duplicated and activates this gene in leukemia secondary to chemotherapy with topoisomerase II inhibitors (Huret, 2009).

The chromosomal balanced translocations, which give rise to chimeric genes, are often malignancy‐specific and are still the main road to identifying the genes involved in cancer through positional cloning. Although a lot of rearrangements are now well known, other less frequent ones have yet to be investigated in detail as they could help identify new genes. Several of the genes involved in fusion, are “swingers” as they can be associated with many other partner genes such as RET for example in thyroid cancer. The processes are recurrent as these partner genes are sometimes themselves associated with various partners. This concept of networking between various oncogenes, coupled with the fact that there are only 23,000 genes in humans, suggests that a limited number of genes are involved in oncogenesis.

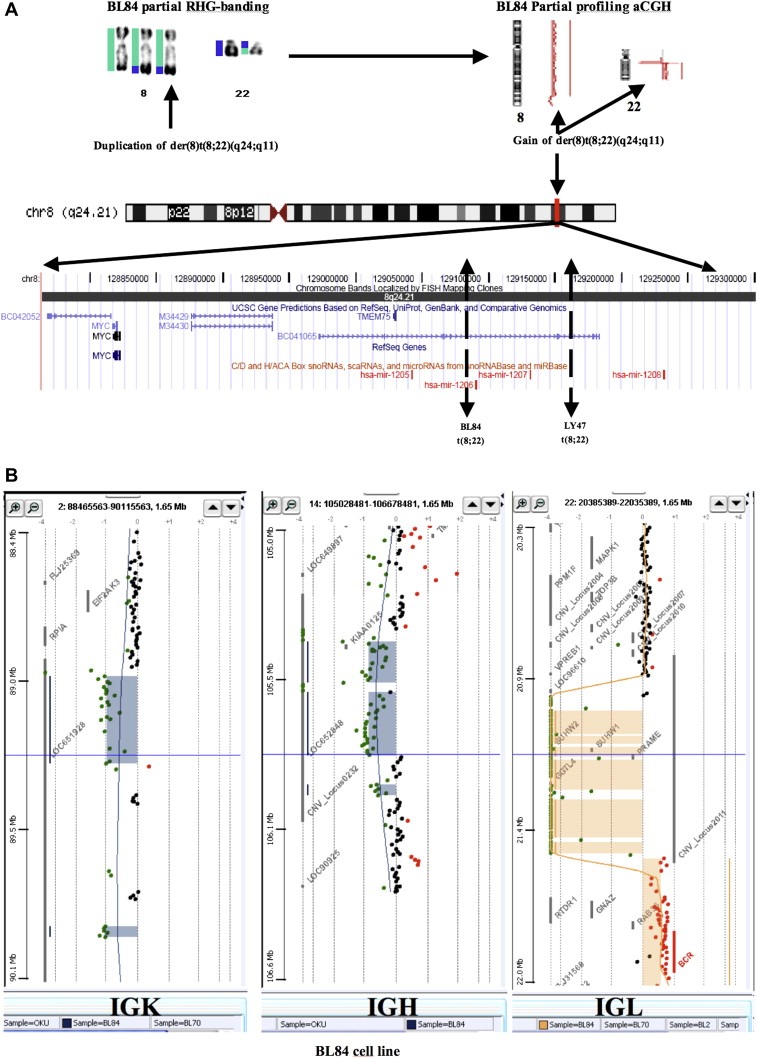

Type II concerns the case of dysregulation of a gene by position effect. The paradigm is Burkitt's lymphoma characterized by the t(8;14) (q24, q32) or its variant, t(2; 8) (p12; q24) or t(8; 22) (q24, q11) (Bernheim et al., 1981a). The MYC gene, localized to 8q24, is dysregulated under the influence of an immunoglobulin heavy chain gene enhancer localized in 14q32. The same mechanism is thought to occur in variant forms with kappa (2p12) or lambda (22q11) light chains despite the distant 3′ breakpoint of MYC and the possible involvement of miRNA (Figure 1) (Toujani et al., 2009). The MYC gene remains structurally intact, although it is the target of numerous punctual mutations. As it occupies the position of the variable part of the immunoglobulin genes, like them, it is submitted to hypermutation possibly induced by AID. These translocations on immunoglobulin genes have been a real key to the discovery of a number of important genes such as BCL1 and BCL2. Isolated from the t(14; 18) (q32, q21) which is specific for non‐Hodgkin centro‐follicular lymphoma, BCL2 is a ubiquitous apoptosis inhibitor.

Figure 1.

Virtual cloning of 8q24 in Burkitt lymphoma showing MYC region breakpoints (modified from Toujani et al., 2009). A) In BL84 and Ly 47 cell lines, characterized by a t(8;22)(q24;q11), the der(8)t(8;22) region harboring the MYC locus was duplicated. For example on BL84, the chromosome 8 (labeled in green) appeared trisomic from pter to 8q24.2, 129.15 Megabases (BL84 partial RHG‐banding), then its ratio on aCGH appeared normal (BL84 Partial profiling aCGH), corresponding to the normal chromosome 8 and to the distal part of the chromosome 8 translocated to the der(22)(BL84 partial RHG‐banding). The breakpoint was observed distal to MYC as expected and is mapped to PVT1, between mir‐1205 and mir‐1206 (Toujani et al., 2009). The chromosome 22 (labeled in blue) from the centromere to the long arm telomere is first non modified. B) Then a complete loss of IGL (immunoglobulin light chain lambda) region is observed suggesting a physiological biallelic rearrangement of IGL, while the t(8;22) occurred during one of them. The IGK (immunoglobulin light chain kappa) and the IGH (immunoglobulin heavy chain) regions are also physiologically rearranged on a single allele (A & B). After this lost region, from 22q11 to qter, 21.58–49.05 Megabases, the chromosome 22 is trisomic.

Type III, is the gain of genetic material.

The gain of material is very frequent and may involve whole chromosomes as the result of malsegregation generated by a pathological spindle. Segmental gains result from unbalanced structural chromosomal rearrangements. Their functional significance remains unknown but an increase in gene size with a gain of function is often seen. For example, the MET oncogene is overrepresented in sporadic papillary renal‐cell tumors via a trisomy 7 and the protein is proportionally overexpressed. During acutisation in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML), the Ph chromosome with the BCR‐ABL fusion gene, is often duplicated. Copy number abnormalities are very often segmental due to structural unbalanced chromosomal rearrangements such as the gain of part of 17q in neuroblastomas.

Type IIIa corresponds to gene amplification which is a selective increase in DNA copy number (Sartorius). It can exhibit two cytogenetic aspects. Double minute (DM) chromosomes are self‐replicating extra‐chromosomal acentric rings or episomes that were initially shown in metaphase and are now easily found in interphase cells. Generally, there is considerable heterogeneity from cell to cell in the number of DM, even if the mean number is high. In some instances, the DM can be expulsed from the nucleus and even from the cell (Valent et al., 2001). The other aspect of gene amplification is homogenously staining regions (HSR) where multiple copies of a genomic region are integrated into chromosome(s) in the form of block(s) of repeat amplicons. They are produced by a break‐fusion‐bridge process that remains in the cycling process until the optimal amount of gene expression is achieved. MYCN oncogene amplification in neuroblastoma which is often observed in tumor cells as DM is generally observed as HSR(s) in the culture‐established cell lines generated from these tumor cells. Some human cell lines however harbor DM such as SW613 (Guillaud‐Bataille et al., 2009), with a MYC amplification linked to tumorigenesis in mice, but also another population of DM derived from 14q24.1 that were purported to contribute to maintaining amplification in the form of DMs (Guillaud‐Bataille et al., 2009).

The amplification can involve a series of oncogenes, whose sequence does not appear to be impaired, such as ERBB2, MYCN, MYC, CCND1, GLI, MDM2, ALK (Huret, 2010; Santarius et al., 2010) but also gene fusion as in some alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma with the t(1;13) translocation (Table 2). The number of copies of a DNA sequence that constitute genome amplification is variously described but generally considered greater than 4‐fold relative to a non‐amplified marker in a haploid genome. In diploid cells this would be equivalent to at least 8 copies. For example, this definition is used for MYCN amplification which is associated with a poor outcome in neuroblastoma (Schwab, 2004). ERBB2 amplification which is deemed present when the mean FISH ratio of ERBB2_HER2 versus the centrometric probe of chromosome 7, calculated after examining 60 cells, is greater than 2 or if more than 6 copies/nucleus are found. This is required to be eligible for anti‐ERBB2 therapeutic agents. Positive ERBB2‐amplified cases are distinct from cases that are equivocal for ERBB2 gene amplification (Couturier et al., 2008). As the copy number in tissues is measured extensively by array‐ or PCR‐based techniques, the criteria for genomic amplification are frequently wrongly based on thresholds that are specific for the normal experimental variations experienced, thus mixing gain and real genetic amplification.

Type IV corresponds to the loss of genetic information, either through deletion, unbalanced translocation, or any other mechanism leading to the loss of heterozygosity (LOH), including acquired parental unidisomy, be it complete or segmental. Loss of function by point mutation is in this category (Albertson et al., 2003; Chin and Gray, 2008). These frequent rearrangements, diagnosed by the loss of heterozygosity (LOH), losses of material by microarrays, FISH or karyotype, often involve tumor suppressor genes (e.g. RB, RET, BRCA1, P53 genes) (Huret, 2010). They are involved in predisposition to many types of cancer. Other losses of function can affect genome repair genes, caretaker or gatekeeper genes. These losses can affect non coding genes such as miRNA that are non randomly lost in the same malignancy (Calin and Croce, 2009; Croce, 2009).

9. Evolution of chromosomal abnormalities in tumors

Although the concept of primary abnormality and additional anomalies is very important, it needs to be revisited. There are numerous examples, such as leukemia, where a recurrent chromosomal abnormality such as the t(9;22)(q34;q11) translocation in CML, was conjointly observed with the t(15;17)(q22;q21) in promyelocytic AML. Only the t(9;22) was observed after treatment. The two abnormalities were again present in the same cells at relapse (Castaigne et al., 1984). Another example is lymphomas, where a recurrent chromosomal abnormality such as the t(8; 14)(q24, q32) translocation in Burkitt's lymphoma, is conjointly observed with the t(14;18) of follicular lymphoma (Tomita et al., 2009). This suggests that these alterations have cumulative effects, if not synergistic. They are commutative, as the order in which they occur does not always appear to be important. In solid tumors, complex chromosomal abnormalities reflect the multistep process of oncogenesis and tumor progression. There are striking examples of profiles that show the multiple subclones in a single tumor as for example in progression towards gene amplification. Cell tolerance to alterations in the genome means mayhem in genome maintenance. In some cases, the alteration is exclusively local, with most of the chromosomes exhibiting a normal profile. In others there are multiple rearrangements culminating in genomic “storms” with highly rearranged chromosomal regions shown by aCGH. Telomeres also appear to play a key role in controlling the number of cell divisions, through gradual terminal truncation. The inactivation of this control introduces a form of chromosomal instability with telomeric fusions followed by random breaks inducing cell death, but it may also select the cell with damaged genomic material and allow it to recover telomerase function (O'Sullivan and Karlseder, 2010). Cancer cell lines with a highly rearranged karyotype can maintain stability throughout the cell culture passages, which indicates that rearranged chromosomes are not intrinsically unstable. It is possible that the dynamic process of Darwinian selection of the cancer genome leads to some form of stable pathologic disease. Some tumors, that have a mutator phenotype, exhibit few visible chromosomal abnormalities.

The evolution of the chromosomal abnormalities is classic during disease progression. It may occur as its natural history such as the evolution of an indolent follicular lymphoma with a single t(14;18) to an aggressive diffuse lymphoma with multiple abnormalities added to the initial translocation (Yunis et al., 1989). A post‐therapeutic relapse often keeps several chromosomal rearrangements from the initial proliferation, but some of the initial ones may be lost and new ones may be acquired. This can lead to a search for residual disease with wrongly targeted probes.

10. Lesions and tumors secondary to physical or chemical mutagens

Alkylating agents or radiotherapy currently used to treat cancers induce chromosomal breakage which is the manifestation of the genotoxic activity of such drugs. The doses commonly used are in a range that allows tolerable toxicity. Patients suffering from Fanconi disease who have a congenital deficit in DNA repair are highly susceptible to these agents which induce acute toxicity with extensive chromosomal breakage (Berger et al., 1980; Moldovan and D'Andrea, 2009).

In a few standard patients, secondary therapy‐induced AML may occur five to seven years after successful treatment of the initial malignancy. It then has specific abnormalities such as −5/5q−, −7/7q−, 12p−. Topoisomerase II‐targeted drugs (ATII), such as etoposide and anthracyclines, may induce the second type of t‐AML. It occurs in a median of 2 years and is not preceded by MDS. Cytogenetic analysis shows a high frequency of rearrangements of chromosome band 11q23 but also recurrent balanced rearrangements such as t(8;21), t(15;17) and inv(16) (Qian et al., 2009).

Secondary tumors can also occur in the absence of treatment but through irradiation accidents. Patients irradiated after Chernobyl (Tronko et al., 2006) showed a specificity for radiation‐induced rearrangements in thyroid tumors, particularly affecting RET (Nikiforov, 2006).

11. Targeted therapies

Chromosomal abnormalities in malignancy have been pivotal in the discovery of targeted therapy against cancer cells. One of the first successes came from the discovery that patients suffering from Fanconi anemia were highly sensitive to Endoxan, a bifunctional alkylating drug used in the late 70s for bone marrow graft conditioning (Berger et al., 1980). A specific reduced‐dose cytotoxic conditioning was proposed for Fanconi patients allowing successful bone marrow grafts (Gluckman et al., 1980). That was the first application of therapy following cytogenetic findings.

Retinoic acid in promyelocytic leukemia (PML), initially proposed in China, induced the maturation of leukemic cells and the patients achieved a complete remission (Wang and Chen, 2008). It was rapidly linked to the AML M3 specific t(15;17) and when the cloning of the breakpoints in PML and RARA (Retinoic Acid Receptor Alpha) genes was done, a physiopathological mechanism appeared.

The paradigm of CML had become the rule in only ten years. This malignant proliferation is caused by the constitutively active chimeric tyrosine kinase BCR‐ABL. This protein is encoded by a BCR‐ABL fusion gene caused by the t(9; 22) (q34, q11) translocation designated as the Philadelphia chromosome or Ph (Nowell and Hungerford, 1960; Rowley, 1973).

The Imatinib discovery program was initiated with the aim of rationally developing a targeted anticancer approved drug. A lead compound was identified from a screen for inhibitors of protein kinase C. During the sophisticated optimization of the molecule structure (Buchdunger et al., 1996; Toledo et al., 1999), researchers observed that a modification had induced an inhibitory effect on tyrosine kinases. This property was then carefully enhanced while PKC inhibition was suppressed and molecule solubility was increased by other structural adjustments in order to allow oral intake. Among the TKs tested, PDGFR and c‐KIT were strongly inhibited by this small molecule as well as BCR‐ABL in cell lines and animal models. In 1998, the first patient with CML was treated. Imatinib was so efficient and devoid of major toxicity that the phase III trial was initiated after only two years and 10 months later the FDA approved Imatinib for Ph+ leukemia. As usual, the design process took around 8 years, but the clinical development was remarkably rapid (Druker, 2009; Sherbenou and Druker, 2007). Thus a second fusion gene, a concept initiated by somatic geneticists from gene mapping, either cytogeneticist or molecular biologists, has been successfully targeted. The fact that a major pharmaceutical laboratory made such a breakthrough without losing money on a specific drug for a limited number of patients opened the way for targeted drugs against proteins specifically modified by genetic changes in cancer.

Imatinib (Gleevec®), induces apoptosis of Ph+, BCR‐ABL cells in patients, with clinically impressive results: most patients are in complete cytogenetic remission. Molecular remission can occur but it is not the rule. This remission seems to persist under permanent treatment. There is some primary and secondary resistance caused by either overrepresentation of the Ph chromosome, additional chromosomal rearrangements or mutations at the active site. Those acute leukemias with the Philadelphia chromosome can also respond to the drug but results are less consistent and relapses are frequent. A second and even third generation of molecules, Dasatinib, Nilotinib, has been developed that could inhibit most resistant ABL mutations and could help to achieve better patient compliance.

Imatinib is active in other diseases with a constitutionally active tyrosine kinase. GIST (Gastro‐Intestinal Stromal Tumor) with a KIT mutation respond to it (Duffaud and Le Cesne, 2009). So does an infrequent myeloproliferative disorder, belonging to idiopathic hypereosinophilia which is due to a fusion between FIP1L1 and PDGFRA resulting from an interstitial deletion in 4q12. Imatinib inhibits the chimeric gene by acting on PDGFRA (Cools et al., 2003). Dermatofibrosarcomas protuberans, a slowly growing cutaneous tumor is characterized by a t(17;22) and a COL1A1‐PDGFB fusion gene whose protein is inhibited by Imatimib (Duffaud and Le Cesne, 2009).

Other targeted drugs against products of rearranged genes exist in solid tumors. The epidermal growth factor receptor 2 ERBB2 (HER2), another tyrosine kinase gene, is often amplified in breast cancer in the form of HSRs (Andre et al., 2009). Among other tyrosine kinases, Lapatinib can inhibit ERBB2 in breast cancer. Trastuzamab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against ERRB2, has demonstrated activity. It is now currently prescribed to women with a gene amplification because survival is longer. This amplification is diagnosed by immunohistochemistry and/or ISH (Couturier et al., 2008; Hanna, 2001).

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) can be either amplified or mutated in a subset of non‐small‐cell lung cancers (NSCLC) (Dahabreh et al., 2010; Sholl et al., 2009). Gefetinib, Erlotinib are inhibitors of EGFR and approved for use against those cancers. Cetuximab and Panitunmumab are monoclonal antibodies against EGFR. The first one has been approved for the treatment of head and neck cancer and both are indicated in colon cancer. Many other drugs are under development.

12. Role of clinical cytogenomics in the diagnosis, prognosis and in monitoring residual disease

Chromosomal rearrangements are now used clinically as markers of malignancy.

It is well established that in leukemias and lymphomas, several rearrangements are highly associated with a particular type of leukemia (Huret, 2010). For example, a t(15;17) is seen exclusively in acute promyelocytic leukemia, and this anomaly has become part of the definition of the entity. That chromosomal abnormalities play a prognostic role is now an integral part of common practice since most treatment protocols stratify patients according to their karyotype.

The diagnosis of chromosome alterations is required for the typing and subtyping of sarcomas. The EML‐ALK fusion gene is sought in lung cancer by FISH. The prognosis of neuroblastoma is now stratified not only on MYCN amplification but on segmental rearrangements shown by aCGH. The presence of segmental copy number aberrations in neuroblastomas means stratification into a poor prognosis group (Janoueix‐Lerosey et al., 2009). Cerebral tumors are also stratified following genomic investigations, like breast tumors, lung cancers and many other types of cancers.

The diagnosis of residual disease which generally requires quantification can be assessed using two complementary methods. The first, quantitative real‐time PCR, is a reliable and sensitive technique, and it yields statistical results. Another approach is FISH which is less sensitive, but it provides a true estimate of malignant cells present. The metaphasic karyotype has proven clinically very relevant for monitoring CML. These methods are widely used to detect residual diseased cells in hematology. In solid tumors, the diagnosis of relapses can benefit from genomic knowledge of a primary tumor in order to design specific probes to show targeted chromosomal rearrangements.

13. Databases

Knowledge of cancer genetics is now too massive and is moving too fast to be fully apprehended by a single individual. For example, more than 3000 genes are involved in cancer which is about 14% of the total number of existing genes. It requires a collective effort facilitated by Web tools that allow interactive consultation. For example, the Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Hematology (Huret, 2010), is a free Internet database that provides summary information and updates on genes, chromosomal abnormalities, and clinical entities in onco‐hematology. It contains multiple links to the multiple genomic databases that are expanding like mushrooms. Indexed by ‘Current Content’, it is considered a scientific journal of international repute and more than 1400 international authors are involved in this work. With thousands of hits per day, it has been top ranked by Google for the words “chromosome+cancer”.

The NCBI/NCI (National Cancer Institute) had created the Cancer Chromosomes initiative (NCI and NCBI, 2001) which is based on three databases: the SKY/M‐FICH & CGH database, the NCI Mitelman Database of Chromosome Aberrations in Cancer which identifies the published cases (Mitelman et al., 2003), and the NCI Recurrent aberrations in Cancer database. Each site has its own characteristics and they are more complementary than competitive.

Moreover, the human genome sequence has generated fantastic tools to investigate the genome of malignant cells. The identification of genes potentially involved in translocation, the ability to generate highly specific oligonucleotide primers, genetic interpretation of array copy number analysis and whole genome sequencing analysis are among the possibilities now available.

14. Prospects

Genomic abnormalities are being increasingly used for the diagnosis, prognosis, treatment and to monitor patients in order to achieve personalized treatment for cancer. The information obtained from karyotype studies, high‐resolution array CGH, mitoses and nuclei using FISH and from cells using PCR will be consistent but each technique will contribute its specificity: karyotype versatility, high‐resolution aCGH detection of unexpected events, focused FISH analysis of tumor cells enabling the differentiation of the proportion of malignant cells and the very strong sensitivity of PCR. Whole genome sequencing will be increasingly used in a not too distant future. We are currently experiencing a period of progressive generalization that is far from simple. Tumor material is not readily accessible and possible changes in practices will be needed. Malignant cell enrichment is often required. PCR may detect recurrent translocations for the diagnosis but it is currently incapable of diagnosing additional abnormalities that may be innumerable.

15. Conclusion

Acquired chromosomal abnormalities are now considered as causal in malignant proliferations. Recurrent chromosomal abnormalities, their additive character combined with their multiplicity in a single tumor are obvious paths in the multi‐stage process of Darwinian oncogenesis. It allows specific chromosomal signatures to be identified in more and more tumors coexisting with possible heterogeneity of the karyotype from one cell to another, or from a subclone to another. Genomic abnormalities are known as the tip of the iceberg because many small rearrangements go unnoticed and new ones are described each month. Considerable work is still needed in clinical solid tumor cytogenomics. This approach has proven successful since it has allowed (and still allows) the identification of a lot of genes involved in oncogenesis. The black box that remains the core of a cancer cell is now becoming dark grey. Beyond progress in concepts and classifications, the designation of targets for new drugs is creating a new paradigm for cancer therapy. The pharmaceutical industry has proven all its skills in chemistry, leaving hope for a numerous progeny to target oncogenes while finding suitable models for highly specific drugs with possibly, a more limited market than that observed conventionally. The monotherapy, circumvented by resistance, will be replaced by a combination of new and old therapies.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Lorna Saint Ange for editing and Bernard Caillou for helpful discussions.

Bernheim Alain, (2010), Cytogenomics of cancers: From chromosome to sequence, Molecular Oncology, 4, doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.06.003.

References

- Albertson, D. , Collins, C. , McCormick, F. , Gray, J. , 2003. Chromosome aberrations in solid tumors. Nat. Genet. 34, 369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre, F. , Job, B. , Dessen, P. , Tordai, A. , Michiels, S. , Liedtke, C. , Richon, C. , Yan, K. , Wang, B. , Vassal, G. , Delaloge, S. , Hortobagyi, G.N. , Symmans, W.F. , Lazar, V. , Pusztai, L. , 2009. Molecular characterization of breast cancer with high-resolution oligonucleotide comparative genomic hybridization array. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argani, P. , Lui, M.Y. , Couturier, J. , Bouvier, R. , Fournet, J.C. , Ladanyi, M. , 2003. A novel CLTC-TFE3 gene fusion in pediatric renal adenocarcinoma with t(X;17)(p11.2;q23). Oncogene. 22, 5374–5378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmain, A. , 2001. Cancer genetics: from Boveri and Mendel to microarrays. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 1, 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, R. , Bernheim, A. , Gluckman, E. , Gisselbrecht, C. , 1980. In vitro effect of cyclophosphamide metabolites on chromosomes of Fanconi anaemia patients. Br. J. Haematol. 45, 565–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim, A. , Berger, R. , Lenoir, G. , 1981. Cytogenetic studies on African Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines: t(8;14), t(2;8) and t(8;22) translocations. Cancer. Genet. Cytogenet. 3, 307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheim, A. , Berger, R. , Preud'homme, J.L. , Labaume, S. , Bussel, A. , Barot-Ciorbaru, R. , 1981. Philadelphia chromosome positive blood B lymphocytes in chronic myelocytic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 5, 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beroukhim, R. , Mermel, C.H. , Porter, D. , Wei, G. , Raychaudhuri, S. , Donovan, J. , Barretina, J. , Boehm, J.S. , Dobson, J. , Urashima, M. , McHenry, K.T. , Pinchback, R.M. , Ligon, A.H. , Cho, Y.J. , Haery, L. , Greulich, H. , Reich, M. , Winckler, W. , Lawrence, M.S. , Weir, B.A. , Tanaka, K.E. , Chiang, D.Y. , Bass, A.J. , Loo, A. , Hoffman, C. , Prensner, J. , Liefeld, T. , Gao, Q. , Yecies, D. , Signoretti, S. , Maher, E. , Kaye, F.J. , Sasaki, H. , Tepper, J.E. , Fletcher, J.A. , Tabernero, J. , Baselga, J. , Tsao, M.S. , Demichelis, F. , Rubin, M.A. , Janne, P.A. , Daly, M.J. , Nucera, C. , Levine, R.L. , Ebert, B.L. , Gabriel, S. , Rustgi, A.K. , Antonescu, C.R. , Ladanyi, M. , Letai, A. , Garraway, L.A. , Loda, M. , Beer, D.G. , True, L.D. , Okamoto, A. , Pomeroy, S.L. , Singer, S. , Golub, T.R. , Lander, E.S. , Getz, G. , Sellers, W.R. , Meyerson, M. , 2010. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across. Nature. 463, 899–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignell, G.R. , Santarius, T. , Pole, J.C. , Butler, A.P. , Perry, J. , Pleasance, E. , Greenman, C. , Menzies, A. , Taylor, S. , Edkins, S. , Campbell, P. , Quail, M. , Plumb, B. , Matthews, L. , McLay, K. , Edwards, P.A. , Rogers, J. , Wooster, R. , Futreal, P.A. , Stratton, M.R. , 2007. Architectures of somatic genomic rearrangement in sequence-level resolution. Genome Res. 17, 1296–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveri, T. , 1914. Zur Frage der Entstehung Maligner Tumoren Gustav Fisher; Jena: [Google Scholar]

- Buchdunger, E. , Zimmermann, J. , Mett, H. , Meyer, T. , Muller, M. , Druker, B.J. , Lydon, N.B. , 1996. Inhibition of the Abl protein-tyrosine kinase in vitro and in vivo by a 2-phenylaminopyrimidine derivative. Cancer Res. 56, 100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin, G.A. , Croce, C.M. , 2009. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: interplay between noncoding RNAs and protein-coding genes. Blood. 114, 4761–4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camparo, P. , Vasiliu, V. , Molinie, V. , Couturier, J. , Dykema, K.J. , Petillo, D. , Furge, K.A. , Comperat, E.M. , Lae, M. , Bouvier, R. , Boccon-Gibod, L. , Denoux, Y. , Ferlicot, S. , Forest, E. , Fromont, G. , Hintzy, M.C. , Laghouati, M. , Sibony, M. , Tucker, M.L. , Weber, N. , Teh, B.T. , Vieillefond, A. , 2008. Renal translocation carcinomas: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and gene expression profiling analysis of 31 cases with a review of the literature. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 32, 656–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaigne, S. , Berger, R. , Jolly, V. , Daniel, M.T. , Bernheim, A. , Marty, M. , Degos, L. , Flandrin, G. , 1984. Promyelocytic blast crisis of chronic myelocytic leukemia with both t(9;22) and t(15;17) in M3 cells. Cancer. 54, 2409–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin, L. , Gray, J.W. , 2008. Translating insights from the cancer genome into clinical practice. Nature. 452, 553–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools, J. , DeAngelo, D. , Gotlib, J. , Stover, E. , Legare, R. , Cortes, J. , Kutok, J. , Clark, J. , Galinsky, I. , Griffin, J. , Cross, N. , Tefferi, A. , Malone, J. , Alam, R. , Schrier, S. , Schmid, J. , Rose, M. , Vandenberghe, P. , Verhoef, G. , Boogaerts, M. , Wlodarska, I. , Kantarjian, H. , Marynen, P. , Coutre, S. , Stone, R. , Gilliland, D. , 2003. A tyrosine kinase created by fusion of the PDGFRA and FIP1L1 genes as a therapeutic target of imatinib in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1201–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier, J. , Vincent-Salomon, A. , Mathieu, M.C. , Valent, A. , Bernheim, A. , 2008. Diagnosis of HER2 gene amplification in breast carcinoma. Pathol. Biol. (Paris). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce, C.M. , 2009. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 704–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahabreh, I.J. , Linardou, H. , Siannis, F. , Kosmidis, P. , Bafaloukos, D. , Murray, S. , 2010. Somatic EGFR mutation and gene copy gain as predictive biomarkers for response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 291–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delattre, O. , Zucman, J. , Plougastel, B. , Desmaze, C. , Melot, T. , Peter, M. , Kovar, H. , Joubert, I. , Dejong, P. , Rouleau, G. , Aurias, A. , Thomas, G. , 1992. Gene fusion with an ETS DNA-binding domain caused by chromosome translocation in human tumours. Nature. 359, 162–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delattre, O. , Zucman, J. , Melot, T. , Garau, X.S. , Zucker, J.M. , Lenoir, G.M. , Ambros, P.F. , Sheer, D. , Turc-Carel, C. , Triche, T.J. , 1994. The Ewing family of tumors – a subgroup of small-round-cell tumors defined by specific chimeric transcripts. N. Engl. J. Med. 331, 294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker, B.J. , 2008. Translation of the Philadelphia chromosome into therapy for CML. Blood. 112, 4808–4817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker, B.J. , 2009. Perspectives on the development of imatinib and the future of cancer research. Nat. Med. 15, 1149–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffaud, F. , Le Cesne, A. , 2009. Imatinib in the treatment of solid tumours. Target. Oncol. 4, 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagin, J.A. , 2002. Perspective: lessons learned from molecular genetic studies of thyroid cancer – insights into pathogenesis and tumor-specific therapeutic targets. Endocrinology. 143, 2025–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frohling, S. , Dohner, H. , 2008. Chromosomal abnormalities in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 722–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselsson, D. , 2001. Chromosomal instability in cancer: causes and consequences. Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman, E. , Devergie, A. , Schaison, G. , Bussel, A. , Berger, R. , Sohier, J. , Bernard, J. , 1980. Bone marrow transplantation in Fanconi anaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 45, 557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaud-Bataille, M. , Brison, O. , Danglot, G. , Lavialle, C. , Raynal, B. , Lazar, V. , Dessen, P. , Bernheim, A. , 2009. Two populations of double minute chromosomes harbor distinct amplicons, the MYC locus at 8q24.2 and a 0.43-Mb region at 14q24.1, in the SW613-S human carcinoma cell line. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 124, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, W. , 2001. Testing for HER2 status. Oncology. 61, 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huret, J. , 2009. MLL (myeloid/lymphoid or mixed lineage leukemia). Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. URL: http://AtlasGeneticsOncology.org/Genes/MLL.html [Google Scholar]

- Huret, J.L. , 2010. Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. [Google Scholar]

- Huret, J.L. , Dessen, P. , Bernheim, A. , 2001. Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. 29, 303–304. updated. Nucl. Acids Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janoueix-Lerosey, I. , Schleiermacher, G. , Michels, E. , Mosseri, V. , Ribeiro, A. , Lequin, D. , Vermeulen, J. , Couturier, J. , Peuchmaur, M. , Valent, A. , Plantaz, D. , Rubie, H. , Valteau-Couanet, D. , Thomas, C. , Combaret, V. , Rousseau, R. , Eggert, A. , Michon, J. , Speleman, F. , Delattre, O. , 2009. Overall genomic pattern is a predictor of outcome in neuroblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 1026–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallioniemi, A. , Kallioniemi, O.P. , Sudar, D. , Rutovitz, D. , Gray, J.W. , Waldman, F. , Pinkel, D. , 1992. Comparative genomic hybridization for molecular cytogenetic analysis of solid tumors. Science. 258, 818–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir, G. , Preud'homme, J.L. , Bernheim, A. , Berger, R. , 1981. Correlation between variant translocation and the expression of immunoglobulin light chains in Burkitt-type lymphomas and leukemias. C. R. Seances Acad. Sci. III. 293, 427–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir, G.M. , Preud'homme, J.L. , Bernheim, A. , Berger, R. , 1982. Correlation between immunoglobulin light chain expression and variant translocation in Burkitt's lymphoma. Nature. 298, 474–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, A. , Morton, C. , 2007. Uterus: leiomyoma. Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. [Google Scholar]

- Mandahl, N. , 2000. Soft tissue tumors: lipoma/benign lipomatous tumors. Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, R.S. , Tomlins, S.A. , Callahan, K. , Ghosh, A. , Nyati, M.K. , Varambally, S. , Palanisamy, N. , Chinnaiyan, A.M. , 2009. Induced chromosomal proximity and gene fusions in prostate cancer. Science. 326, 1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis, E.R. , 2009. New strategies and emerging technologies for massively parallel sequencing: applications in medical research. Genome Med. 1, 40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardis, E.R. , Ding, L. , Dooling, D.J. , Larson, D.E. , McLellan, M.D. , Chen, K. , Koboldt, D.C. , Fulton, R.S. , Delehaunty, K.D. , McGrath, S.D. , Fulton, L.A. , Locke, D.P. , Magrini, V.J. , Abbott, R.M. , Vickery, T.L. , Reed, J.S. , Robinson, J.S. , Wylie, T. , Smith, S.M. , Carmichael, L. , Eldred, J.M. , Harris, C.C. , Walker, J. , Peck, J.B. , Du, F. , Dukes, A.F. , Sanderson, G.E. , Brummett, A.M. , Clark, E. , McMichael, J.F. , Meyer, R.J. , Schindler, J.K. , Pohl, C.S. , Wallis, J.W. , Shi, X. , Lin, L. , Schmidt, H. , Tang, Y. , Haipek, C. , Wiechert, M.E. , Ivy, J.V. , Kalicki, J. , Elliott, G. , Ries, R.E. , Payton, J.E. , Westervelt, P. , Tomasson, M.H. , Watson, M.A. , Baty, J. , Heath, S. , Shannon, W.D. , Nagarajan, R. , Link, D.C. , Walter, M.J. , Graubert, T.A. , DiPersio, J.F. , Wilson, R.K. , Ley, T.J. , 2009. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1058–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman, F. , Johansson, B. , Mertens, F. , 2003. Database of Chromosome Aberrations in Cancer http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Chromosomes/Mitelman [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman, F. , Johansson, B. , Mertens, F. , 2007. The impact of translocations and gene fusions on cancer causation. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 7, 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan, G.L. , D'Andrea, A.D. , 2009. How the fanconi anemia pathway guards the genome. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 223–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCI, NCBI, 2001. NCI and NCBI's SKY/M-FISH and CGH Database http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sky/skyweb.cgi [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforov, Y.E. , 2006. Radiation-induced thyroid cancer: what we have learned from chernobyl. Endocr. Pathol. 17, 307–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforova, M.N. , Nikiforov, Y.E. , 2009. Molecular diagnostics and predictors in thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 19, 1351–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforova, M.N. , Stringer, J.R. , Blough, R. , Medvedovic, M. , Fagin, J.A. , Nikiforov, Y.E. , 2000. Proximity of chromosomal loci that participate in radiation-induced rearrangements in human cells. Science. 290, 138–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, P.C. , Hungerford, D.A. , 1960. Chromosome studies on normal and leukemic human leukocytes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 25, 85–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan, R.J. , Karlseder, J. , 2010. Telomeres: protecting chromosomes against genome instability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 171–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierotti, M. , 2001. Chromosomal rearrangements in thyroid carcinomas: a recombination or death dilemma. Cancer Lett. 166, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkel, D. , Albertson, D.G. , 2005. Array comparative genomic hybridization and its applications in cancer. Nat Genet. 37, (Suppl) S11–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleasance, E.D. , Cheetham, R.K. , Stephens, P.J. , McBride, D.J. , Humphray, S.J. , Greenman, C.D. , Varela, I. , Lin, M.L. , Ordonez, G.R. , Bignell, G.R. , Ye, K. , Alipaz, J. , Bauer, M.J. , Beare, D. , Butler, A. , Carter, R.J. , Chen, L. , Cox, A.J. , Edkins, S. , Kokko-Gonzales, P.I. , Gormley, N.A. , Grocock, R.J. , Haudenschild, C.D. , Hims, M.M. , James, T. , Jia, M. , Kingsbury, Z. , Leroy, C. , Marshall, J. , Menzies, A. , Mudie, L.J. , Ning, Z. , Royce, T. , Schulz-Trieglaff, O.B. , Spiridou, A. , Stebbings, L.A. , Szajkowski, L. , Teague, J. , Williamson, D. , Chin, L. , Ross, M.T. , Campbell, P.J. , Bentley, D.R. , Futreal, P.A. , Stratton, M.R. , 2010. A comprehensive catalogue of somatic mutations from a human cancer genome. Nature. 463, 191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z. , Joslin, J.M. , Tennant, T.R. , Reshmi, S.C. , Young, D.J. , Stoddart, A. , Larson, R.A. , Le Beau, M.M. , 2009. Cytogenetic and genetic pathways in therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia. Chem. Biol. Interact. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggi, N. , Stamenkovic, I. , 2007. The biology of Ewing sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 254, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, J.D. , 1973. Letter: a new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and Giemsa staining. Nature. 243, 290–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, J.D. , 1998. The critical role of chromosome translocations in human leukemias. Annu. Rev. Genet. 32, 495–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, A. , 2002. Cytogenetics and molecular genetics of bone and soft-tissue tumors. Am. J. Med. Genet. 115, 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarius, T. , Shipley, J. , Brewer, D. , Stratton, M.R. , Cooper, C.S. , 2010. A census of amplified and overexpressed human cancer genes. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 10, 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schvartzman, J.M. , Sotillo, R. , Benezra, R. , 2010. Mitotic chromosomal instability and cancer: mouse modelling of the human disease. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 10, 102–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, M. , 2004. MYCN in neuronal tumours. Cancer Lett. 204, 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbenou, D.W. , Druker, B.J. , 2007. Applying the discovery of the Philadelphia chromosome. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2067–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholl, L.M. , Yeap, B.Y. , Iafrate, A.J. , Holmes-Tisch, A.J. , Chou, Y.P. , Wu, M.T. , Goan, Y.G. , Su, L. , Benedettini, E. , Yu, J. , Loda, M. , Janne, P.A. , Christiani, D.C. , Chirieac, L.R. , 2009. Lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR amplification has molecular features in never-smokers. Cancer Res. 69, 8341–8348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soda, M. , Choi, Y.L. , Enomoto, M. , Takada, S. , Yamashita, Y. , Ishikawa, S. , Fujiwara, S. , Watanabe, H. , Kurashina, K. , Hatanaka, H. , Bando, M. , Ohno, S. , Ishikawa, Y. , Aburatani, H. , Niki, T. , Sohara, Y. , Sugiyama, Y. , Mano, H. , 2007. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion cancer. Nature. 448, 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow, S.H. , Campo, E. , Harris, N.L. , Jaffe, E.S. , Pileri, S.A. , Stein, H. , Thiele, J. , Vardiman, J.W. , 2008. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues fourth ed. WHO Press; Geneva: [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.B. , 2009. Attacking cancer at its root. Cell. 138, 1051–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, L.M. , Lydon, N.B. , Elbaum, D. , 1999. The structure-based design of ATP-site directed protein kinase inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 6, 775–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita, N. , Tokunaka, M. , Nakamura, N. , Takeuchi, K. , Koike, J. , Motomura, S. , Miyamoto, K. , Kikuchi, A. , Hyo, R. , Yakushijin, Y. , Masaki, Y. , Fujii, S. , Hayashi, T. , Ishigatsubo, Y. , Miura, I. , 2009. Clinicopathological features of lymphoma/leukemia patients carrying both BCL2 and MYC translocations. Haematologica. 94, 935–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toujani, S. , Dessen, P. , Ithzar, N. , Danglot, G.L. , Richon, C. , Vassetzky, Y. , Robert, T. , Lazar, V. , Bosq, J. , Da Costa, L. , Pérot, C. , Ribrag, V. , Patte, C. , Wiels, J.e. , Bernheim, A. , 2009. High resolution genome-wide analysis of chromosomal alterations in Burkitt's lymphoma. PLoS ONE. 4, e7089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronko, M.D. , Howe, G.R. , Bogdanova, T.I. , Bouville, A.C. , Epstein, O.V. , Brill, A.B. , Likhtarev, I.A. , Fink, D.J. , Markov, V.V. , Greenebaum, E. , Olijnyk, V.A. , Masnyk, I.J. , Shpak, V.M. , McConnell, R.J. , Tereshchenko, V.P. , Robbins, J. , Zvinchuk, O.V. , Zablotska, L.B. , Hatch, M. , Luckyanov, N.K. , Ron, E. , Thomas, T.L. , Voilleque, P.G. , Beebe, G.W. , 2006. A cohort study of thyroid cancer and other thyroid diseases after the chornobyl accident: thyroid cancer in Ukraine detected during first screening. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 98, 897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valent, A. , Venuat, A.M. , Danglot, G. , Da Silva, J. , Duarte, N. , Bernheim, A. , Benard, J. , 2001. Stromal cells and human malignant neuroblasts derived from bone marrow metastasis may share common karyotypic abnormalities: the case of the IGR-N-91 cell line. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 36, 100–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.Y. , Chen, Z. , 2008. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: from highly fatal to highly curable. Blood. 111, 2505–2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunis, J.J. , Mayer, M.G. , Arnesen, M.A. , Aeppli, D.P. , Oken, M.M. , Frizzera, G. , 1989. bcl-2 and other genomic alterations in the prognosis of large-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 320, 1047–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]