Abstract

Background

Although β-blockers increase survival in patients with heart failure (HF), the mechanisms behind this protection are not fully understood, and not all patients with HF respond favorably to them. We recently demonstrated that, in cardiomyocytes, a reciprocal down-regulation occurs between β1-adrenergic receptors (ARs) and the cardioprotective sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor-1 (S1PR1).

Objectives

The authors hypothesized that, in addition to salutary actions due to direct β1AR-blockade, agents such as metoprolol (Meto) may improve post-myocardial infarction (MI) structural and functional outcomes via restored S1PR1 signaling, and sought to determine mechanisms accounting for this effect.

Methods

We tested the in vitro effects of Meto in HEK293 cells and in ventricular cardiomyocytes isolated from neonatal rats. In vivo, we assessed the effects of Meto in MI wild-type and β3AR knockout mice.

Results

Here we report that, in vitro, Meto prevents catecholamine-induced down-regulation of S1PR1, a major cardiac protective signaling pathway. In vivo, we show that Meto arrests post-MI HF progression in mice as much as chronic S1P treatment. Importantly, human HF subjects receiving β1AR-blockers display elevated circulating S1P levels, confirming that Meto promotes S1P secretion/signaling. Mechanistically, we found that Meto-induced S1P secretion is β3AR-dependent because Meto infusion in β3AR knockout mice does not elevate circulating S1P levels, nor does it ameliorate post-MI dysfunction, as in wild-type mice.

Conclusions

Our study uncovers a previously unrecognized mechanism by which β1-blockers prevent HF progression in patients with ischemia, suggesting that β3AR dysfunction may account for limited/null efficacy in β1AR-blocker–insensitive HF subjects.

Keywords: β-adrenergic receptors, β-blocker, myocardial infarction, sphingosine 1-phosphate

INTRODUCTION

Signaling through myocyte G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), particularly β-adrenergic receptors (β1, β2, and β3ARs), regulates the rate and force of contraction in response to increased workload (1). However, after myocardial infarction (MI), this signaling is profoundly altered, and cardiac βAR dysregulation and desensitization largely account for chronic post-MI decompensation (2). Accordingly, βAR-blockers attenuate the noxious effects of sympathetic catecholamines on the heart and prevent further βAR down-regulation. These compounds remain crucial to improving survival and preventing further left ventricular (LV) decompensation in patients who have experienced an ischemic event (1,3). Clinical β-blocker use is unequivocally proven to reduce oxygen consumption, prevent cardiac adverse remodeling, blunt cardiomyocyte apoptosis, inhibit βAR down-regulation, and reduce the risk of fatal arrhythmias (4). Yet, whether correcting βAR molecular perturbations justifies all mechanisms of β-blocker-induced cardioprotection in HF is a relevant question, as additional mechanisms appear to participate. Moreover, because not all patients respond to β-blockers, the overall clinical experience raises the question of how exactly β-blockers attenuate progression of HF after MI. Furthermore, delineating whether distinct, clinically-useful β-blockers have different mechanisms may explain specific patient responses and lead to fine-tuning of personalized HF therapy.

β-Blockers, such as alprenolol and carvedilol, act as classical receptor antagonists. However, they can also stimulate signaling pathways in a G protein–independent fashion (5). Moreover, selective β1AR-blockers, such as metoprolol (Meto) or nebivolol, can also promote β3AR up-regulation and/or activity in the heart, thus enhancing the cardioprotective signaling of this βAR subtype (6–8). Thus, answering these mechanistic questions is important, and may help tailor β-blockade therapies for patients with HF. Herein, we evaluated the role of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1), a key GPCR expressed in the heart, which mediates the cardioprotective effect of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a natural lysophospholipid that appears tightly linked to β1AR-signaling (9,10). In fact, β1AR down-regulation can occur after S1P stimulation, whereas S1PR1 down-regulation can be triggered by isoproterenol (ISO) treatment (9). This direct receptor cross-talk is also physiologically relevant, as these GPCRs interact and show reciprocal down-regulation in a rat model of post-MI HF (9). For these reasons, we hypothesize that, aside from the protective effects of β-blockade against catecholamine damage or βAR regulation in the myocardium (11), there are additional beneficial effects involving S1P and S1PR1 signaling.

Methods

AGONISTS AND INHIBITORS

S1P was purchased from Cayman Chemicals (26993-30-6, Ann Arbor, Michigan); ISO (I6504), BRL 37344 (B169), and Meto (M5391) were all purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri).

CELL CULTURE AND TRANSFECTION

Neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (NRVMs) were isolated from the hearts of 1- to 2-day-old rats, as previously described (12). HEK293 cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Virginia) were transfected as previously described (9).

CELL FRACTIONATION AND WESTERN BLOT ANALYSIS

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (12). Protein levels of S1PR1 (Y080010, ABM Inc, Richmond, Canada; 1: 1,000), SphK1 (sc-48825, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas; 1: 1,000), SphK2 (ab37977, Abcam, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1: 1,000), β3AR (PAB8502, Abnova, Walnut, California, 1: 1,000); glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (sc-32233, 6C5, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, 1: 2,000) were assessed. Plasma membrane proteins were isolated from NRVMs, as previously described (12).

ANIMAL MODELS AND EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Temple University School of Medicine. For in vivo experiments, we used wild-type C57BL/6 mice and global β3AR knockout (KO) mice (13). All animals (females and males, 9 to 12 weeks of age) were bred and maintained on a C57BL/6 background.

The β3AR KO genotype was assessed using specific primers: wild-type (WT) forward 5′ GTTGCGAACTGTGGACGTCAGTGG 3′; KO forward 5′ CGCATCGCCTTCTATCGCCTTCTTG 3′; and KO/WT reverse (common) 5′ AATGCCGTTGGCGCTTAGCCAC 3′

Surgically-induced MI was performed as previously described (14). Seven days post-MI, mice were randomly assigned to 1 of the following groups: MI; MI + Meto; MI + S1P; and MI + Meto/S1P. Meto was administered in drinking water (250 mg/kg/day) (15), whereas S1P (10 μM) was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and was continuously infused subcutaneously into mice via an osmotic mini-pump (ALZET, DURECT Co., Cupertino, California) (16). Transthoracic echocardiography was performed to assess cardiac structure and function at baseline, 7 days, and 4 weeks post-MI, using a VisualSonics VeVo 2100 system (VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada), as previously described (12).

HISTOLOGY

Cardiac-specimens were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. After deparaffinization and rehydration, 5-μm-thick sections were prepared, mounted on glass slides, and stained with 1% Sirius Red in picric acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri) to detect interstitial fibrosis, as previously described (12). Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) was performed as previously described (12).

ANALYSIS AND STATISTICS

All procedures in mice were performed in a blinded fashion. Moreover, all LV tissue and blood samples derived from them were also coded, and the operators were blind to these codes until data quantification was complete. Data are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical significance was determined by a Student t-test or Mann-Whitney U test when sample size was <10. For multiple comparisons, 1-way analysis of variance, followed by Bonferroni post hoc correction, was performed. All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software version 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California).

RESULTS

METO PREVENTS ISO-INDUCED IN VITRO S1PR1 MEMBRANE DOWN-REGULATION

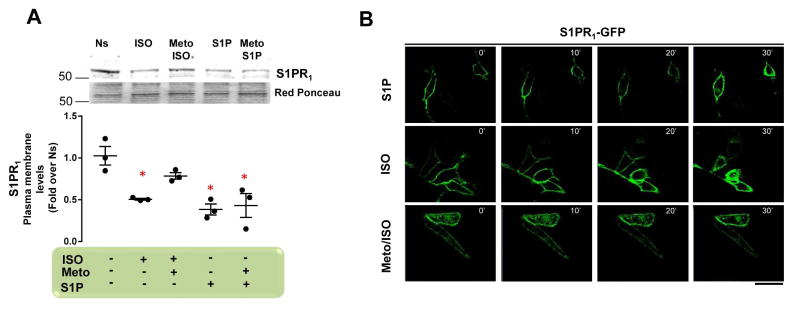

The βAR agonist ISO induces robust internalization and/or desensitization of the S1P receptor (S1PR1), leading to inhibition of its protective signaling, which is dependent on down-regulation of β1AR (9,10). Here, we tested whether selective β1AR-blockade via Meto affects this reciprocal β1AR-S1PR1 down-regulation. To this end, we first treated neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) with ISO (1 μM) and S1P (250 nM) (each for 30 min), which resulted in a robust S1PR1 plasma membrane down-regulation (Figure 1A). Next, we pre-treated NRVMs with Meto (10 μM) for 30 min, and then stimulated them with ISO (1 μM) or S1P (250 nM) for an additional 30 min. Pre-treatment of cells with Meto prevented ISO-, but not S1P-induced S1PR1 down-regulation (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Meto Abolishes β1AR-Dependent Sarcolemmal S1PR1 Internalization.

(A) Representative immunoblots (upper panels) and densitometric quantitative analysis (lower panel) of multiple (n = 3) independent experiments to evaluate S1PR1 in crude plasma membrane preparations from NRVMs. Cells were nonstimulated (Ns) or stimulated with ISO (1 μM) or S1P (250 nM) for 30 min. Before ISO or S1P stimulation, a group of cells was pre-treated with Meto (10 μM) for 30 min. Ponceau Red staining was used to assess total protein loading. *p < 0.05 versus Ns. (B) Representative immunofluorescence images (scale bar: 10 μm) of HEK293 cells overexpressing β1AR-Flag and S1PR1-GFP (green). S1PR1-GFP internalization over a 30-min time course (0 to 30 min) in cells treated with ISO (1 μM) or S1P (250 nM) is shown. Before ISO stimulation, a group of cells was pre-treated with Meto (10 μM for 30 min). β1AR = beta-1 adrenergic receptor; GFP = green fluorescent protein; ISO = isoproterenol; Meto = metoprolol; NRVM = neonatal rat ventricular myocytes; S1P = sphingosine-1-phosphate; S1PR1 = sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1;

To confirm these observations, we used HEK293 cells over-expressing both FLAG-tagged β1AR (β1AR-FLAG) and green fluorescent protein tagged S1PR1 (S1PR1-GFP) (Online Figure 1A) and checked for S1PR1 internalization. Using confocal microscopy, we performed a time course evaluation (0 to 30 min), assessing the impact of Meto on ISO- and S1P-induced S1PR1 internalization. In line with the NRVM data, we observed that ISO and S1P induced massive receptor internalization, and that Meto prevented ISO-induced effects (Figure 1B). Together, these data indicate that β1AR-blockade prevents β1-dependent S1PR1 down-regulation in vitro.

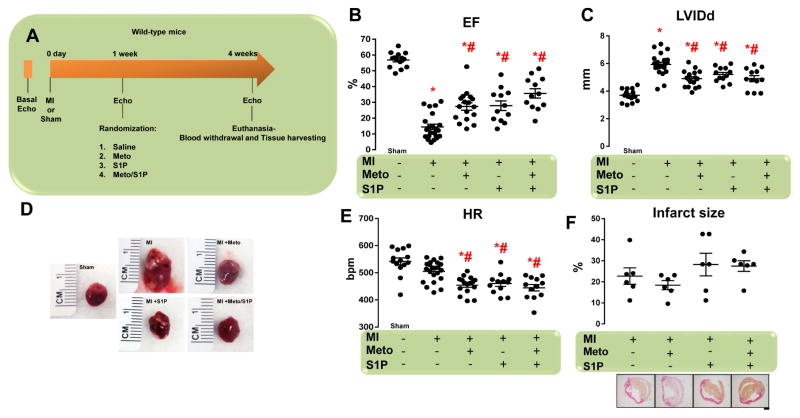

BOTH METO AND S1P IMPROVE CONTRACTILITY AND PREVENT LV REMODELING AFTER MI

For in vivo support of the findings described in the preceding section, we used a mouse MI model because both β1AR and S1PR1 are down-regulated in infarcted myocardium (9). Five groups of randomized mice were studied: 1) sham-operated; 2) untreated MI; 3) MI treated with Meto (250 mg·kg−1·day−1); 4) MI treated with S1P (10 μM); and 5) MI treated with both Meto and S1P (Meto + S1P). LV function and dimensions were evaluated by echocardiography before MI, and then 1 (Online Figures 2A and 2B) and 4 weeks after MI (study termination) (Figure 2A). Four weeks after MI, echocardiographic analysis revealed that LV ejection fraction (EF) was markedly decreased, and LV dimensions and dilation were substantially enlarged in untreated post-MI mice, as opposed to sham-operated animals (Figures 2B–2D). However, Meto administration resulted in improved LV contractility (Figure 2B) and reduced LV dilation (Figure 2C–2D), as compared with untreated post-MI mice. S1P treatment also significantly increased EF and reduced the LV diameter versus control MI mice (Figure 2B–2D). Although Meto and S1P were compatible for coadministration, we did not observe any synergistic effects of these therapies (Figures 2B–2D). Interestingly, Meto and S1P, either alone or in combination, decreased heart rate (Figure 2E). Of note, the percentage of infarct size (measured at the end of the study) was similar among all study groups (Figure 2F).

Figure 2. Meto Ameliorates MI-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction and S1PR1 Down-Regulation.

(A) Overall design of 4-week study of MI in mice. Echocardiography was performed at day 0 and then MI were surgically induced. Sham-operated mice were used as controls. After 1 week, echocardiography was performed in order to assess that all mice had similar cardiac dysfunction. Mice (total n = 12 to 22 per group) were randomized for treatments: MI (controls), MI + Meto (250 mg/kg/day), MI + S1P (10 μM) and MI + Meto/S1P. Four weeks post-MI (3 weeks post-treatment), echocardiography was performed and animals euthanized for tissue harvesting. (B–C) Dot plots showing the echocardiographic analysis performed at the end of the study period (4 weeks post-MI) of (B) left ventricular ejection fraction (EF, %) and (C) left ventricular internal diameter at diastole (LVIDd) of individual mice from each of the groups. (D) Representative images of whole hearts from mice. (E) Dot plots showing echocardiographic analysis of heart rate of individual mice from the each of the groups. (F) Dot plots (upper panel) and representative panels of picrosirius red staining (lower panels; scale bar: 500 μm) showing the percentage of infarct size in the MI, MI + Meto, MI + S1P, and MI + Meto/S1P mice (n = 6). For (B, C, and E) *p < 0.05 versus sham; #p < 0.05 versus MI. Echo = echocardiogram; MI = myocardial infarction. Other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

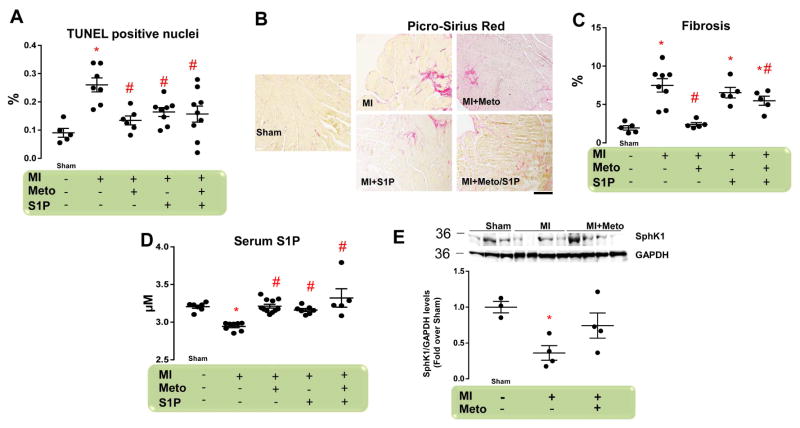

BOTH METO AND S1P REDUCE POST-MI CARDIAC APOPTOSIS AND FIBROSIS

Cardiac apoptosis and fibrosis are 2 major hallmarks of post-MI cardiac remodeling (12,17). Therefore, we compared the impact of Meto and/or S1P on these endpoints. As expected, cardiomyocyte cell death and collagen deposition were significantly increased in post-MI untreated mice versus sham animals (Figures 3A and 3B). These changes were accompanied by the up-regulation of profibrotic genes encoding connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), and type 1 (Col1) and type 3 collagen (Col3) (Online Figures 2A–2C). Importantly, Meto treatment induced a marked reduction of both cardiac fibrosis and apoptosis (Figures 3A and 3B and Online Figures 3A–3C). Conversely, S1P treatment significantly prevented MI-dependent apoptosis (Figure 3A), but had no effect on cardiac fibrosis (Figure 3B and Online Figures 3A–3C). Moreover, combined Meto + S1P treatment did not improve upon Meto alone in preventing the MI-induced increase in apoptotic rate and fibrosis (Figures 3A and 3B and Online Figures 3A–C).

Figure 3. Effects of Meto and S1P on Post-Ischemic Cardiac Fibrosis and Apoptosis.

(A) Dot plots showing myocyte cell death via TUNEL staining from the following groups (n = 5 to 9): sham; MI; MI + Meto (250 mg/kg/d); MI + S1P (10 μM); and MI + Meto/S1P. (B) Representative images (scale bar: 200 μm) and (C) quantitative data showing the percentage of cardiac fibrosis via picrosirius red staining from each of the groups (n = 5 to 8). (D) S1P serum levels measured by ELISA assay in each of the groups (n = 7 to 11). (E) Representative immunoblots (upper panels) and densitometric quantitative analysis (lower panel) of multiple independent (n = 3 to 4) experiments to evaluate SphK1 protein levels in total cardiac lysates from each of the groups. GAPDH levels were used for protein loading controls. For (A, C–E) *p < 0.05 versus sham; #p < 0.05 versus MI. ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GAPDH = glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; SphK1 = sphingosine kinase-1; TUNEL = terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling. Other abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 2.

The lack of any additional effect of Meto + S1P compared to Meto alone prompted us to further investigate the effects of Meto and S1P. In particular, we measured circulating S1P serum levels in all of our study groups. We found that although S1P in serum was significantly reduced in MI untreated mice compared with sham, Meto treatment was able to restore circulating S1P to sham levels (Figure 3D). As expected, S1P administration normalized circulating S1P levels, both when administered alone or with Meto (Figure 3D). Importantly, the impact of Meto on circulating S1P levels was paralleled by the rescued cardiac sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1) expression (Figure 3E) and activity (Online Figure 4A). SphK1 is the enzyme involved in S1P production and consequent S1PR1 activation (18). Of relevance, Meto obviated the S1P secretion deficiency found in post-MI WT mice (Online Figure 4B).

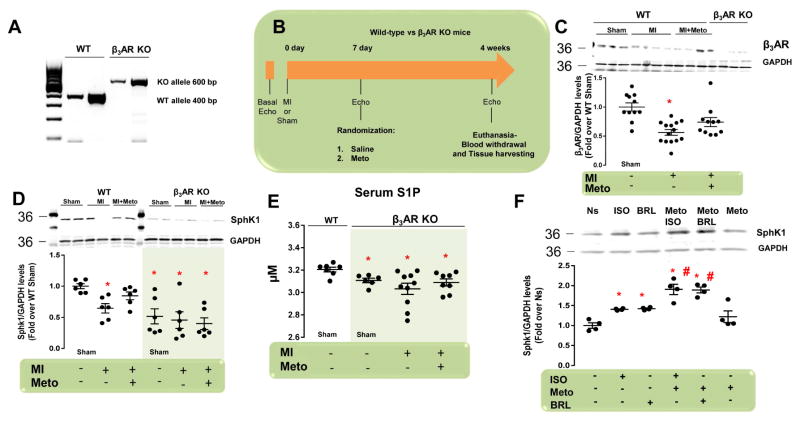

METO RESCUES B3AR-DEPENDENT SPHK1 EXPRESSION IN INFARCTED HEARTS

To date, there is no molecular mechanism explaining how β-blockers lead to S1P production. Normally, β3ARs, which are expressed at low levels in the myocardium, can be up-regulated and activated by Meto (6,19). Moreover, due to metabolic effects (1), the β3AR is implicated in regulation of SphK1 expression and S1P release, without affecting SphK2 (20). Thus, we tested whether β3AR signaling accounts for Meto-induced post-MI cardioprotection using β3AR KO and WT mice. At 1 week after MI, all animal groups had similar LV dysfunction (Online Figures 5A and 5B). We then randomized mice to placebo or Meto treatment (Figures 4A and 4B). At the end of the study period, we found significant down-regulation of cardiac β3AR protein levels in post-MI WT mice versus sham-operated animals (Figure 4C). Notably, Meto obviated this change (Figure 4C). As expected, β3AR protein levels were not detectable in β3AR KO mice (Figure 4C). Consistent with our previous studies (9), cardiac SphK1, SphK2 protein levels, and circulating S1P were all reduced after MI in WT mice with respect to sham (Figures 4D and 4E and Online Figure 6). Treatment with Meto restored SphK1 expression (Figures 4D and 4E and Online Figure 6). Intriguingly, SphK1 expression and S1P secretion were very low in β3AR KO mice, regardless of MI and/or Meto status. Of note, SphK2 expression was similar in WT and in β3AR KO mice. In aggregate, this evidence strongly supports the contention that β3AR per se plays a crucial role in basal expression levels of SphK1 in the heart (Figures 4D and 4E).

Figure 4. β3AR-Dependent Expression/Activation of Cardiac SphK1 and S1P Secretion in MI Mice Following Meto Treatment.

(A) Representative genotype analyses of mice (in duplicate) with WT (400 bp), or deleted (600 bp) β3AR alleles. (B) Overall design of 4-week study in WT and β3AR KO mice. Echocardiography was performed at day 0, followed by surgically-induced MI. Sham-operated mice were used as controls. After 1 week, echocardiography was performed in order to assess that all mice had similar cardiac dysfunction, and they were then randomized for treatments: MI (controls) and MI + Meto. (C) Representative immunoblots (upper panels) and densitometric quantitative analysis (lower panel) of multiple independent experiments (n = 10 to 13) to evaluate β3AR protein levels in total cardiac lysates from the following groups of WT mice: sham; MI; and MI + Meto. Total cardiac lysates from β3AR KO mice were used as a negative control. GAPDH levels were used for protein loading. *p < 0.05 versus sham. (D) Representative immunoblots (upper panels) and densitometric quantitative analysis (lower panel) of multiple independent experiments (n = 6) to evaluate SphK1 protein levels in total cardiac lysates from the following groups: WT (sham, MI, and MI + Meto) and β3AR KO (sham, MI, and MI + Meto). GAPDH levels were used for protein loading controls. *p < 0.05 versus WT sham. (E) S1P blood serum levels measured by ELISA in the following groups (n = 7 to 10): WT (sham) and β3AR KO (sham, MI, and MI + Meto). *p <0.05 versus WT sham. (F) Representative immunoblots (upper panels) and densitometric quantitative analysis (lower panel) of multiple (n = 4) independent experiments to evaluate SphK1 protein levels in NRVMs Ns or stimulated with ISO (1 μM) or BRL (1 μM) for 12 h. Before ISO or BRL stimulation a group of cells was pre-treated with Meto (10 μM for 30 min). *p < 0.05 versus Ns; #p < 0.05 versus ISO. KO = knockout; WT = wild-type. Other abbreviations as in Figures 1–3.

To confirm the role of β3AR on SphK1 expression, we treated NRVMs with ISO (10 μM) or with the β3AR agonist BRL 37344 (BRL, 1 μM) for 12 h. Before ISO or BRL stimulation, some groups of cells were also pre-treated with Meto (10 μM) for 30 min. Both ISO and BRL were able to induce SphK1 up-regulation, as compared with control, nonstimulated (Ns) cells (Figure 4F). More importantly, Meto pre-treatment robustly enhanced the ability of ISO and BRL to increase SphK1 expression. Meto alone enhanced SphK1 at levels comparable to those found in Ns cells (Figure 4F). Thus, Meto rescues β3AR-dependent SphK1 expression through direct β1AR blockade, making more catecholamines available for β3AR activation and inhibitory G protein (Gi) coupling. In fact, pre-treatment of NRVMs with the Gi inhibitor pertussis toxin (PTX, 100 ng/ml for 18 h) prevented SphK1 up-regulation due to ISO or BRL (Online Figure 7).

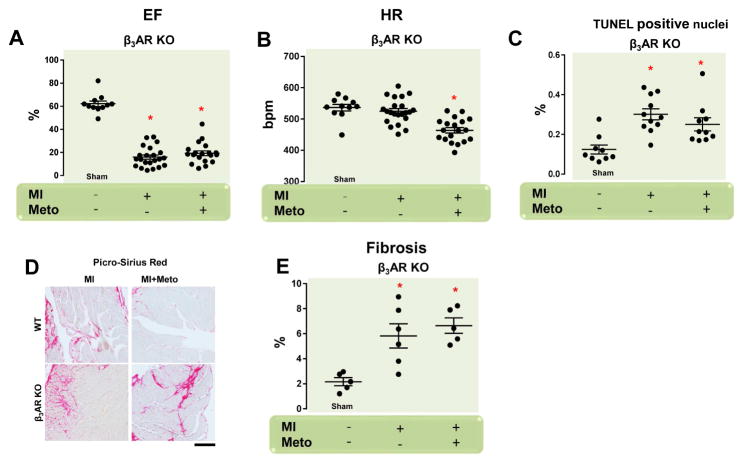

METO-INDUCED IMPROVEMENT IN POST-MI HF DEPENDS ON BOTH β3AR AND S1PR1

The data presented so far suggests that S1PR1 resensitization and β3AR activation are important components of Meto-induced beneficial effects post-MI. To solidify this view, we compared the in vivo cardiac effects of Meto in post-MI WT and β3AR KO mice. Meto improved cardiac function in post-MI WT mice, but not β3AR KO mice (Figures 2B and 5A), despite a similar heart rate reduction in both groups (Figures 2E and 5B). Infarct sizes in β3AR KO mice were similar under any experimental conditions (Online Figure 8), and no differences in cardiac function were observed between WT and β3AR KO mice following MI (Figure 5A). Consistently, apoptosis and fibrosis were also similar in WT and β3AR KO mice after MI (Figures 3A–3E). In contrast, whereas Meto reduced both of these endpoints in post-MI WT mice, it did not in β3AR KO mice (Figures 3A–3C and 5C–5E). Finally, to confirm the role of S1PR1 in Meto-mediated cardioprotection, infarcted WT mice were treated with the S1PR1 antagonist W146. MI mice were randomized to 1 of the following groups: MI + vehicle (PBS + ethanol); MI + Meto (250 mg/kg/d); MI + W146 (8 μg/ml) (21); and MI + Meto/W146. W146 was administered via mini-osmotic pumps, as done with S1P. As expected, Meto prevented LV dysfunction and adverse remodeling (Online Figure 9), and these beneficial actions were prevented by W146 (Online Figure 9). Either vehicle or W146, taken alone had no sizable impact on post-MI decompensation. Thus, activation of the β3AR/S1PR1 axis accounts for the protection against MI afforded by Meto.

Figure 5. Lack of Meto-Dependent Post-MI Therapeutic Response in β3AR KO Mice.

(A,B) Dot plots showing echocardiographic analysis of (A) left ventricular ejection fraction (EF, %) and (B) heart rates of individual mice from the following groups (n = 11 to 22): β3AR KO (sham, MI, and MI + Meto). (C) Dot plots showing myocyte cell death via TUNEL staining from the following groups of mice (n = 5): β3AR KO (sham, MI, and MI + Meto); (D,E). Representative images (scale bar: 200 μm) and quantitative data showing percentage of cardiac fibrosis via picrosirius red staining from the β3AR KO (sham, MI, and MI + Meto) mouse groups (n = 5). For (A–C, E) *p < 0.05 versus sham. Abbreviations as in Figures 1–4.

CHRONIC TREATMENT WITH METO INCREASES CIRCULATING S1P LEVELS IN HUMAN HF PATIENTS

To add clinical relevance to our findings, we investigated whether β1-blocker treatment can affect circulating S1P levels in human patients with HF. Patients treated with β1AR antagonists and a similar HF group not treated with β-blockers (see Online Table 1 for specific patient characteristics) were used to asses S1P levels via an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Interestingly, clinical β1-blockade was characterized by significantly higher blood S1P levels compared with the β-blocker-naïve control population (Online Figure 10).

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that the selective β1-blocker Meto rescues S1PR1- dependent signaling by preventing β1AR-induced S1PR1 down-regulation, which attenuates HF progression after MI in mice. This effect requires up-regulation of β3AR signaling, which leads to increased circulating S1P levels and cardiac S1PR1 stimulation, ultimately inducing prosurvival signals in the ischemic myocardium. Accordingly, the salutary actions of Meto are completely lost in β3AR KO mice. Hence, the present study documents a previously unrecognized mechanism by which β1-blockers, such as Meto, effectively improve survival and mitigate LV decompensation in mice with ischemic HF.

β1-Blockers remain a forefront approach for treating acute or chronic HF of ischemic and nonischemic origin. They prevent direct cardiac catecholamine toxicity and promote βAR down-regulation in the failing heart, resulting in markedly reduced HF-related mortality (1). However, β1-blockers are a heterogeneous class of drugs, and some appear to attenuate HF progression through mechanisms additive to βAR resensitization and prevention of catecholamine-induced damage. Uncovering these unknown modalities of protection may help tailor βAR-blocker therapies for each HF patient. In the present study, we focused on β1ARs and S1PR1s, 2 distinct, highly-expressed cardiac GPCRs, whose cross-talk appears to have important pathophysiological repercussions (9). In a rat model of post-MI HF, where S1P is significantly reduced and catecholamine secretion is increased, we previously found that β1AR-hyperstimulation leads to marked S1PR1 signaling dysregulation (9). Therefore, in this study, we tested whether, among other salutary actions, β1AR-blockers are also able to tip the balance to favor S1PR1 protective signaling. Accordingly, we show that Meto pre-treatment of cardiomyocytes in vitro abolishes ISO-induced S1PR1 down-regulation, whereas no effect is detectable in presence of S1P stimulation, confirming that β1AR activation could lead to S1PR1 transactivation. We validated these in vitro findings in a relevant in vivo HF model in mice after MI. We found that Meto treatment rescued LV function and prevented further adverse LV remodeling, restoring, at least in part, S1PR1 cardiac plasma membrane levels. S1PR1 mediates the effect of S1P, which is a natural cardioprotective sphingolipid present at high concentrations in blood (9). Data showing that increasing cardiac S1PR1 levels contributed to significantly reduce myocyte apoptosis and fibrosis in post-MI hearts treated with Meto is confirmed by the fact that combining S1P and Meto had beneficial effects similar to those exerted by Meto alone. In keeping with this, we found that chronic administration of this selective β1-blocker was sufficient to restore circulating S1P levels, which were markedly reduced after MI. In turn, this increased bioavailability activated cardiac SphK1, which was ultimately responsible for the rise in S1P levels in the serum of Meto-treated infarcted mice. Of note, this rise was superimposable to that achieved after direct infusion of S1P in post-MI mice. Taken together, this evidence explains why combining S1P and Meto had no additional or synergistic effects. This conclusion not only points toward new and important mechanistic insights into the beneficial effects of β1-blockade in ischemic HF, but also stresses the functional repercussions of a loss of cardiac S1P-S1PR1 signals due to β1AR-hyperstimulation after ischemic injury. In essence, our study represents a significant departure from previous in vitro and in vivo data showing that only direct S1PR1 activation confers cardioprotection after an ischemic insult (22–26).

Another conceptual advancement offered by the present findings is the involvement of β3ARs in Meto-induced protection involving the S1P-S1PR1 axis. β3ARs were recently proposed to be cardioprotective receptors, with nodal roles in cardiac metabolism involving regulation of lipolysis via enhanced Sphk1 activity (20). Our present findings significantly expand this view by showing that following MI, β3AR expression is substantially down-regulated, along with markedly reduced SphK1 expression, and consequent impaired S1P secretion and worse LV remodeling. The dependence of SphK1/S1P signaling downstream of β3AR activation is supported by the severe down-regulation of both SphK1 and S1P levels in β3AR KO mice, and that these levels do not differ significantly from those found in WT mice after MI. Congruent with this, we observed similar LV dysfunction in post-MI WT and β3AR KO mice. Nevertheless, the most striking finding is that Meto not only restores cardiac S1PR1, but also prevents β3AR down-regulation after MI, resulting in enhanced SphK1 activity and consequent S1P secretion. These biological effects were not seen in β3AR KO mice. Meto did not consistently prevent HF progression in infarcted β3AR KO mice. Thus, our data reveal that activating the β3AR signal is a crucial and required step for β1AR blockers (and likely other pharmacological interventions impinging on the β1AR signal) because Meto does not improve the HF phenotype in post-MI β3AR KO mice.

Although appearing somewhat modest, Meto or S1P treatment of mice with severe post-MI cardiac dysfunction resulted in a significant protective effect in terms of post-MI viable myocardium or LV function. Importantly, the treatments were started at 1 week post-MI and drugs were administered for just 3 weeks. Therefore, instituting Meto or S1P within the first week post-MI and/or prolonging the treatment up to 8 weeks or more might result in more pronounced effects, as previously demonstrated for S1P (27). These pending questions, along with possible dosing issues, should be addressed in large animals to more firmly establish the therapeutic potential of the present findings obtained in mice. Likewise, future studies to more finely dissect changes in S1PR1 downstream signaling, particularly in β3AR KO mice, are warranted.

All of the evidence reported here appears to be relevant to human HF. In fact, we report for the first time that patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy receiving treated with β1-blockers (Online Table 1 and Online Figure 10) had significantly higher S1P serum levels. At this time, possible β3AR up-regulation in these patients with ischemia receiving β1-blockers can only be inferred from evidence obtained in post-MI WT mice. However, a previous report showed up-regulation of β3AR protein levels in heart specimens from human subjects with either ischemic or dilated cardiomyopathy who received chronic treatment with β1AR-blockers, digitalis, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and diuretic agents (28). Overall, these data corroborate our view that it is not the HF condition per se or its etiology, but rather the pharmacological treatment used (i.e., β1-blockers [or others]) that effectively increases cardiac β3AR in these human HF subjects. Additional in-depth studies must be designed to directly address this important point. However, our study suggests another important translational consideration that may help in personalizing β1AR-blocker therapy: the cohort of patients that do not respond or responds minimally to β1-blockers may harbor abnormalities in β3AR signaling.

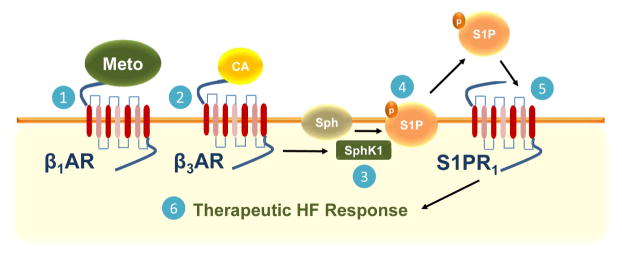

In conclusion, our study documents a novel mechanism by which β1AR-blockers induce a therapeutic response after MI: β1AR blockade by Meto leads to up-regulation of β3ARs, followed by S1P/S1PR1-triggered protective and beneficial signaling. The latter event is followed by β3AR-dependent S1P release outside the cardiomyocytes, which, in turn, activates the rescued S1PR1 aligned on the sarcolemmal membrane of neighboring myocytes to ultimately trigger intracellular protective signaling (Central Illustration; Figure 6). Therefore, Meto acting on myocardial β1ARs actually influences the signaling of 3 distinct receptors, both directly (S1PR1 down-regulation) and indirectly (up-regulation of β3ARs and increased S1P secretion) (Central Illustration; Figure 6). The discovery of this new protective loop triggered by β1AR blockers such as Meto advances our understanding of ischemic HF pathophysiology.

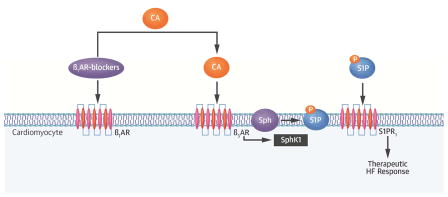

Central Illustration. β1AR-Blocker–Dependent Activation of β3AR/S1P Protective Signaling in Cardiomyocytes.

Following binding with the β1AR, β1AR-blockers prevent direct catecholamine toxicity on the cardiac myocytes. Circulating catecholamines then bind to β3ARs, leading to up-regulation and activation of SphK1, which phosphorylates sphingosine (Sph). The S1P generated is then secreted outside the myocytes, and directly activates S1PR1 in an autocrine and paracrine fashion, which, in turn, induces a therapeutic response in heart failure. β1AR = beta-1 adrenergic receptor; β1AR = beta-3 adrenergic receptor; CA = catecholamine; HF = heart failure; S1P = sphingosine-1-phosphate; S1PR = sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor; SphK1 = sphingosine kinase-1.

Figure 6. Scheme for Metoprolol-Dependent Induction of β3AR and S1PR1 Activity in Cardiomyocytes.

Following binding to the β1AR, Meto prevents direct catecholamine toxicity on the myocardium and further β1AR and S1PR1 down-regulation (1). Circulating catecholamines then bind to β3ARs (2), leading to up-regulation and activation of SphK1 (3), which phosphorylates the sphingolipid sphingosine (Sph) (4). The S1P generated is then secreted outside the myocytes and directly activates S1PR1 in an autocrine and paracrine fashion (5), which, in turn, induces a therapeutic response in HF (6). Thus, blocking β1AR positively affects all 3 receptor systems in failing cardiomyocytes. CA = catecholamine. Other abbreviations as in Figures 1 and 3.

Online Methods

Agonists and inhibitors

W146 was purchased by Cayman Chemicals (909725-62-8, Michigan, USA), Pertrussis Toxin (PTX) was purchased by Sigma (P7208, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)

Confocal Microscopy

HEK293 expressing the S1PR1-GFP and the WT β1AR-Flag were visualized as previously described1. The fluorescent data sets were visualized with a Zeiss 510 confocal laser scanning microscope and analyzed by LSM 510 software.

RNA extraction and Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from NRVMs and from LV specimens with TRizol (Life Technologies, USA) accordingly to the company’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed in duplicate on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR detection system (BioRad Lab. USA) using the SYBR green mix (BioRad Lab. USA) and specific primers for: CTGF (Fwd-5′-GGAAGACACATTTGGCCCAG-3′; Rev-5′-TAGGTGTCCGGATGCACTTT-3′); Col1a2 (Fwd-5′-TAGAAAGAACCCTGCTCGCA-3′; Rev-5′-CGGCTGTATGAGTTCTTCGC-3′) and Col3 (Fwd-5′-ATGAGGAGCCACTAGACTGC-3′; Rev-5′GGTCACCATTTCTCCCAGGA-3′). The expression levels of CTGF, Col1a2 and Col3 were normalized to the rRNA 18S. Specificity of PCR products was confirmed by melting curve and gel electrophoresis.

ELISA assay

Circulating and LV S1P levels were measured using a commercial kit (Echelon), according to manufacturer instructions and as previously described1. About 1 mL and 5 mL of blood were collected from mice and humans respectively. Then the blood was centrifuged to 2,000 rpm a 15°C for 15 minutes and 25 μL of serum were used for the ELISA assay. About 1–2 mg of LV were lysed according to the kit instruction. The lysate was used for the assay.

Sphingosine Kinase activity assay

Cardiac SphK activity was measured using a commercial kit (Echelon), according to manufacturer instructions. About 1–2 mg of LV was lysed according to the kit instruction. The lysate was used for the assay.

In vivo S1PR1 antagonism

Surgical induced MI was performed as previously described23. Seven days post-MI, mice were randomly assigned to one of the following groups: MI, MI+W146 (8μg/mL) MI+Meto, MI+S1P and MI+Meto/S1P. Meto was administered in drinking water (250 mg/Kg/day)24 while S1P (10 μM) was dissolved in PBS and was continuously infused subcutaneously into mice via an osmotic mini-pump (ALZET, DURECT Co., Cupertino, USA)25.

Supplementary Material

Table 1. Characteristic of patients in the overall study population and in β1-blockers–treated and non-treated HF patients

Supplementary Figure 1. Shown is co-expression of β1AR-Flag (Red) and S1PR1-GFP (green) in HEK293 cells (Scale bar: 50 μm).

Bar graphs showing the echocardiographic analysis performed after 1 week post-MI of (A) Left Ventricular (LV) Ejection fraction (EF, %); (B) heart rate (HR) of individual mice (n=7–12 mice per group) from the following group of treatment: Sham, MI, MI+Meto, MI+S1P and MI+Meto/S1P.

Bar graph showing quantitative data of quantitative RT-PCR experiments to evaluate myocardial A) CTGF, B) Col1a2, C) Col3 mRNA levels from the following groups (n=6–8 mice per group) of treatment: Sham, MI, MI+Meto, MI+S1P and MI+Meto/S1P mice. *, p<0.05 vs Sham;

Dot plots showing analysis of A) SphK activity and B) S1P levels measured by ELISA assay in LV lysates from the following groups: WT (Sham, MI and MI+Meto). n=10–13 mice per group for SphK activity and n=6 mice per group for S1P assay: *, p<0.05 vs Sham.

Bar graphs showing echocardiographic analysis of (A) Left ventricular (LV) Ejection fraction (EF, %) and (B) heart rate (HR) of individual mice after 1 week of MI from the following groups (n=17–19 mice per group): β3AR KO (Sham, MI and MI+Meto).

Representative immunoblots (upper panels) and densitometric quantitative analysis (lower panel) of multiple independent experiments (n=4 mice per group) to evaluate SphK2 protein levels in total cardiac lysates from the following group: WT (Sham, MI and MI+Meto) and β3AR KO (Sham, MI and MI+Meto). GAPDH protein levels were used to check protein loading. *, p<0.05 vs WT Sham.

Representative immunoblots (upper panels) and densitometric quantitative analysis (lower panel) of multiple (n=3) independent experiments to evaluate SphK1 protein levels in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) either unstimulated (Ns) or stimulated with Isoproterenol (ISO, 1 μM) or BRL37344 (BRL, 1 μM) for 12 hours. Prior to ISO or BRL stimulation a group of cells was pre-treated with Pertussis Toxin (PTX, 100 ng/mL) for 18 hours. *, p<0.05 vs Ns.

Dot plots showing percentage of infarct size in post-MI β3AR KO mice (n=5 mice per group) treated or not with Meto (250 mg/Kg/d).

A–B) Dot plots showing echocardiographic analysis of (A) Left ventricular (LV) Ejection fraction (EF, %) and (B) heart rate (HR) of individual mice from the following groups (n=7–8 mice per group): WT (MI, MI+W146, MI+Meto and MI+Meto/W146). *, p<0.05 vs MI.

Dot plots showing S1P blood serum levels measured by ELISA assay in human HF-patients treated (n=19) or not (n=20) with β1-blockers. *, p<0.05 vs HF.

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

βAR-blockers are a key component of therapy for patients with HF, but some patients do not respond to this line of treatment. β3-dependent S1P activation is crucial for cardiac protection, and β3 signaling may underlie the differential responsiveness to this class of drugs.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK

Patients with HF who are resistant to β-blockade may harbor structural or functional β3 variants, and therapies that stimulate these selectively might extend the benefit of to a broader segment of the patient population.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- βAR

β-adrenergic receptor

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- HF

heart failure

- ISO

isoproterenol

- Meto

metoprolol

- MI

myocardial infarction

- S1P

sphingosine-1-phosphate

- S1PR1

sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1

- SphK1

sphingosine kinase 1

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. This work was supported by NIH grants R37 HL061690, RO1 HL088503, P01 HL08806, P01 HL075443, and P01 HK091799 (all to Dr. Koch), and RO1 HL063030 (to Dr. Paolocci, as co-PI); American Heart Association 16POST30980005 (to Dr. Cannavo); Italian Ministry of Health-GR-2011-02346878 (to Dr, Rengo); AHA Grant-in-Aid 17070027 (to Dr. Paolocci). The CNIC is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (MEIC) and the Pro CNIC Foundation, and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (SEV-2015-0505).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cannavo A, Liccardo D, Koch WJ. Targeting cardiac β-adrenergic signaling via GRK2 inhibition for heart failure therapy. Front Physiol. 2013;4:264. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bristow MR, Ginsburg R, Minobe W, et al. Decreased catecholamine sensitivity and β-adrenergic-receptor density in failing human hearts. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:205–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207223070401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bristow MR. β-Adrenergic receptor blockade in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2000;101:558–69. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.5.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bristow MR. Treatment of chronic heart failure with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists: a convergence of receptor pharmacology and clinical cardiology. Circ Res. 2011;109:1176–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.245092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim IM, Tilley DG, Chen J, et al. Beta-blockers alprenolol and carvedilol stimulate beta-arrestin-mediated EGFR transactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14555–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804745105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trappanese DM, Liu Y, McCormick RC, et al. Chronic β1-adrenergic blockade enhances myocardial β3-adrenergic coupling with nitric oxide-cGMP signaling in a canine model of chronic volume overload: new insight into mechanisms of cardiac benefit with selective β1-blocker therapy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2015;110:456. doi: 10.1007/s00395-014-0456-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z, Ding L, Jin Z, et al. Nebivolol protects against myocardial infarction injury via stimulation of beta 3-adrenergic receptors and nitric oxide signaling. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aragón JP, Condit ME, Bhushan S, et al. Beta3-adrenoreceptor stimulation ameliorates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via endothelial nitric oxide synthase and neuronal nitric oxide synthase activation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2683–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannavo A, Rengo G, Liccardo D, et al. β1-adrenergic receptor and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) reciprocal downregulation influences cardiac hypertrophic response and progression to heart failure: protective role of S1PR1 cardiac gene therapy. Circulation. 2013;128:1612–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang F, Xia Y, Yan W, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling contributes to cardiac inflammation, dysfunction, and remodeling following myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;310:H250–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00372.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaludercic N, Takimoto E, Nagayama T, et al. Monoamine oxidase A-mediated enhanced catabolism of norepinephrine contributes to adverse remodeling and pump failure in hearts with pressure overload. Circ Res. 2010;106:193–202. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.198366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannavo A, Liccardo D, Eguchi A, et al. Myocardial pathology induced by aldosterone is dependent on non-canonical activities of G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10877. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-Prieto J, García-Ruiz JM, Sanz-Rosa D, et al. β3 adrenergic receptor selective stimulation during ischemia/reperfusion improves cardiac function in translational models through inhibition of mPTP opening in cardiomyocytes. Basic Res Cardiol. 2014;109:422. doi: 10.1007/s00395-014-0422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao E, Lei YH, Shang X, et al. A novel and efficient model of coronary artery ligation and myocardial infarction in the mouse. Circ Res. 2010;107:1445–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harding VB, Jones LR, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ, Rockman HA. Cardiac βARK1 inhibition prolongs survival and augments β blocker therapy in a mouse model of severe heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5809–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091102398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanin M, Germinario E, Dalla Libera L, et al. Trophic action of sphingosine 1-phosphate in denervated rat soleus muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C36–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00164.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannavo A, Rengo G, Liccardo D, et al. Prothymosin alpha protects cardiomyocytes against ischemia-induced apoptosis via preservation of Akt activation. Apoptosis. 2013;18:1252–61. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0876-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takabe K, Paugh SW, Milstien S, Spiegel S. “Inside-out” signaling of sphingosine-1-phosphate: therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:181–95. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma V, Parsons H, Allard MF, McNeill JH. Metoprolol increases the expression of β3-adrenoceptors in the diabetic heart: effects on nitric oxide signaling and forkhead transcription factor-3. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;595:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W, Mottillo EP, Zhao J, et al. Adipocyte lipolysis-stimulated interleukin-6 production requires sphingosine kinase 1 activity. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:32178–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.601096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarkisyan G, Gay LJ, Nguyen N, Felding BH, Rosen H. Host endothelial S1PR1 regulation of vascular permeability modulates tumor growth. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2014;307:C14–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00043.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Honbo N, Goetzl EJ, Chatterjee K, Karliner JS, Gray MO. Signals from type 1 sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors enhance adult mouse cardiac myocyte survival during hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3150–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00587.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeh CC, Li H, Malhotra D, et al. Sphingolipid signaling and treatment during remodeling of the uninfarcted ventricular wall after myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1193–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01032.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vessey DA, Li L, Kelley M, Karliner JS. Combined sphingosine, S1P and ischemic postconditioning rescue the heart after protracted ischemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;375:425–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lecour S, Smith RM, Woodward B, Opie LH, Rochette L, Sack MN. Identification of a novel role for sphingolipid signaling in TNF α and ischemic preconditioning mediated cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:509–18. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin ZQ, Zhou HZ, Zhu P, et al. Cardioprotection mediated by sphingosine-1-phosphate and ganglioside GM-1 in wildtype and PKCε knockout mouse hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1970–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01029.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santos-Gallego CG, Vahi TP, Goliasch G, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist fingolimod increases myocardial salvage and decreases adverse postinfarction left ventricular remodeling in a porcine model of ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation. 2016;133:954–66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.012427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moniotte S, Kobzik L, Feron O, Trochu JN, Gauthier C, Balligand JL. Upregulation of β3-adrenoceptors and altered contractile response to inotropic amines in human failing myocardium. Circulation. 2001;103:1649–55. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.12.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Cannavo A, Rengo G, Liccardo D, et al. β1-adrenergic receptor and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) reciprocal downregulation influences cardiac hypertrophic response and progression to heart failure: protective role of S1PR1 cardiac gene therapy. Circulation. 2013;128:1612–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1. Characteristic of patients in the overall study population and in β1-blockers–treated and non-treated HF patients

Supplementary Figure 1. Shown is co-expression of β1AR-Flag (Red) and S1PR1-GFP (green) in HEK293 cells (Scale bar: 50 μm).

Bar graphs showing the echocardiographic analysis performed after 1 week post-MI of (A) Left Ventricular (LV) Ejection fraction (EF, %); (B) heart rate (HR) of individual mice (n=7–12 mice per group) from the following group of treatment: Sham, MI, MI+Meto, MI+S1P and MI+Meto/S1P.

Bar graph showing quantitative data of quantitative RT-PCR experiments to evaluate myocardial A) CTGF, B) Col1a2, C) Col3 mRNA levels from the following groups (n=6–8 mice per group) of treatment: Sham, MI, MI+Meto, MI+S1P and MI+Meto/S1P mice. *, p<0.05 vs Sham;

Dot plots showing analysis of A) SphK activity and B) S1P levels measured by ELISA assay in LV lysates from the following groups: WT (Sham, MI and MI+Meto). n=10–13 mice per group for SphK activity and n=6 mice per group for S1P assay: *, p<0.05 vs Sham.

Bar graphs showing echocardiographic analysis of (A) Left ventricular (LV) Ejection fraction (EF, %) and (B) heart rate (HR) of individual mice after 1 week of MI from the following groups (n=17–19 mice per group): β3AR KO (Sham, MI and MI+Meto).

Representative immunoblots (upper panels) and densitometric quantitative analysis (lower panel) of multiple independent experiments (n=4 mice per group) to evaluate SphK2 protein levels in total cardiac lysates from the following group: WT (Sham, MI and MI+Meto) and β3AR KO (Sham, MI and MI+Meto). GAPDH protein levels were used to check protein loading. *, p<0.05 vs WT Sham.

Representative immunoblots (upper panels) and densitometric quantitative analysis (lower panel) of multiple (n=3) independent experiments to evaluate SphK1 protein levels in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) either unstimulated (Ns) or stimulated with Isoproterenol (ISO, 1 μM) or BRL37344 (BRL, 1 μM) for 12 hours. Prior to ISO or BRL stimulation a group of cells was pre-treated with Pertussis Toxin (PTX, 100 ng/mL) for 18 hours. *, p<0.05 vs Ns.

Dot plots showing percentage of infarct size in post-MI β3AR KO mice (n=5 mice per group) treated or not with Meto (250 mg/Kg/d).

A–B) Dot plots showing echocardiographic analysis of (A) Left ventricular (LV) Ejection fraction (EF, %) and (B) heart rate (HR) of individual mice from the following groups (n=7–8 mice per group): WT (MI, MI+W146, MI+Meto and MI+Meto/W146). *, p<0.05 vs MI.

Dot plots showing S1P blood serum levels measured by ELISA assay in human HF-patients treated (n=19) or not (n=20) with β1-blockers. *, p<0.05 vs HF.