Abstract

Objective To investigate the efficacy of hypericum extract WS 5570 (St John's wort) compared with paroxetine in patients with moderate to severe major depression.

Design Randomised double blind, double dummy, reference controlled, multicentre non-inferiority trial.

Setting 21 psychiatric primary care practices in Germany.

Participants 251 adult outpatients with acute major depression with total score ≥ 22 on the 17 item Hamilton depression scale.

Interventions 900 mg/day hypericum extract WS 5570 three times a day or 20 mg paroxetine once a day for six weeks. In initial non-responders doses were increased to 1800 mg/day hypericum or 40 mg/day paroxetine after two weeks.

Main outcome measures Change in score on Hamilton depression scale from baseline to day 42 (primary outcome). Secondary measures were change in scores on Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale, clinical global impressions, and Beck depression inventory.

Results The Hamilton depression total score decreased by mean 14.4 (SD 8.8) points, corresponding to 56.6% (SD 34.3%) of the baseline value, in the hypericum group and by 11.4 (SD 8.6) points (44.8% (SD 33.5%) of baseline value) in the paroxetine group (intention to treat analysis; similar results were observed in the per protocol analysis). The intention to treat analysis (lower one sided 97.5% confidence limit 1.5 points for the difference hypericum minus paroxetine) and the per protocol analysis (lower confidence limit 0.7 points) showed non-inferiority of hypericum and statistical superiority over paroxetine. The lower limits in both cases exceeded the pre-specified non-inferiority margin of -2.5 points and the superiority margin of 0. The incidence of adverse events was 0.035 and 0.060 events per day of exposure for hypericum and paroxetine, respectively.

Conclusions In the treatment of moderate to severe major depression, hypericum extract WS 5570 is at least as effective as paroxetine and is better tolerated.

Introduction

Extract of Hypericum perforatum (St John's wort) is more effective than placebo in the treatment of mild to moderate major depression1 and as effective as several tricyclic antidepressants2-5 or fluoxetine.6 In patients with more severe depression, however, the antidepressant efficacy of hypericum extract is disputed. In a comparison of 1800 mg/day hypericum extract (LI 160) and 150 mg/day imipramine the effect of both drugs was comparable during six weeks of acute treatment.4 That study, however, was not sufficiently powered to demonstrate non-inferiority of the herbal extract.

In clinical practice, hypericum extract is better tolerated than synthetic antidepressants.7 It may be particularly helpful in severe depression with its high risk of chronicity.8 We compared the efficacy and safety of hypericum extract with paroxetine in patients with moderate to severe depression.

Hypericum extract WS 5570 at a dose of 300 mg three times a day has been shown to be more effective than placebo in patients with mild to moderate major depression treated for six weeks.9 Paroxetine, on the other hand, is a potent selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with proved efficacy in patients with depression of any severity10 and has a more favourable safety profile than tricyclic antidepressants.11 In major depression, daily doses between 20 mg and 50 mg have been recommended12 and are commonly used in clinical trials and in daily practice.

In accordance with Kupfer's model of acute therapy and subsequent prophylactic treatment of unipolar depression,13 our study included a six week acute phase after which responders undergo four months of prophylactic continuation treatment (to prevent relapse or recurrence, or both).

Methods

Protocol, design, and objectives

This double blind, double dummy, randomised phase III trial examined the efficacy of hypericum extract WS 5570 compared with paroxetine in the acute treatment of moderate to severe major depression. After a screening examination participants underwent a single blind placebo run-in phase of three to seven days, during which they received three coated tablets of hypericum placebo per day plus one paroxetine placebo capsule in the morning. After that, we randomised those still meeting the selection criteria to six weeks of double blind treatment with hypericum extract or paroxetine. Those who responded to treatment (that is, their total score on the 17 item Hamilton depression scale decreased by ≥ 50%) were invited to participate in a four month double blind maintenance phase (reported elsewhere).

All patients provided written informed consent. We did not use a placebo control group because we considered it unethical to treat severely depressed patients with placebo for six weeks.

Participants

We recruited male and female outpatients in 21 psychiatric primary care centres in Germany. All participants were 18-70 years old and had single or recurrent moderate or severe episodes of unipolar major depression without psychotic features (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, (DSM-IV) 296.22, 296.23, 296.32, 296.33) persisting for two weeks to a year. At screening and baseline all participants had to have a total score ≥ 22 points on the 17 item Hamilton depression scale and ≥ 2 points for the item “depressive mood.” The diagnosis of depression was based on the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview.14 There were no restrictions regarding ethnic group.

We excluded anyone with a decrease in total depression score of ≥ 25% during the run-in, or with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, acute anxiety disorder, adjustment disorder, depressive disorder of any type not stated above, bipolar disorder, organic mental disorder, acute post-traumatic stress disorder, or substance abuse disorder. We also excluded patients with increased risk of suicide (defined by a score ≥ 4 for item 10 of the Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale), who had previously attempted suicide, or who had not responded to more than one adequate treatment (equivalent to 150 mg/day amitriptyline for ≥ 6 weeks) in the present episode. Participants were not allowed to take other psychotropic medication and psychotherapy during the study (in case of previous antidepressant medication an appropriate wash out period of five half lives had to be observed).

Interventions and blinding

We used hypericum extract WS 5570 (Dr Willmar Schwabe Pharmaceuticals, Karlsruhe, Germany), a hydroalcoholic extract from herba hyperici (drug to extract ratio 3-7:1) with standardised contents of 3-6% hyperforin and 0.12-0.28% hypericin. The coated tablets contained 300 mg or 600 mg of the extract. Paroxetine was supplied in tablets of 20 mg packed in capsules containing one or two tablets. High and low dose tablets or capsules were indistinguishable in all aspects of their outward appearance. For each drug an identically matched placebo was available (the success of blinding was evaluated by examining the drugs before distribution).

During the six weeks of randomised treatment patients allocated to hypericum always took three coated tablets of hypericum/day plus one paroxetine placebo capsule in the morning whereas those in the paroxetine group took one capsule of paroxetine in the morning and three coated tablets of hypericum placebo/day. Initially this corresponded to three doses of 300 mg/day hypericum or one dose of 20 mg/day paroxetine. For patients whose total depression score had not decreased by at least 20% after two weeks of treatment compared with baseline we increased the treatment to three doses of 600 mg/day hypericum or one dose of 40 mg/day paroxetine. The doses for paroxetine were based on published recommendations.12

Outcomes

We assessed efficacy and safety at screening, baseline, and at the end of the first, second, fourth, and sixth weeks. The primary outcome measure was the absolute decrease of the Hamilton total depression score between baseline and week six. Secondary outcome measures included the Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale, the clinical global impressions, and the Beck depression inventory. We based assessments of safety and tolerability on spontaneous reports of adverse events, a semistructured interview exploring known side effects of the investigational treatments, physical examinations, and routine laboratory measurements.

To assure uniform diagnostic and rating standards, all assessments were performed by psychiatrists and psychologists who had participated in training before patients were included.

Random sequence generation, allocation concealment, implementation

Patients who still met the selection criteria at baseline were randomised at a ratio of 1:1 to hypericum or paroxetine. Randomisation was performed in blocks stratified by trial centre. A biometrician otherwise not involved in the trial generated the code using a validated computer program. The study drugs were dispensed to the centres in numbered containers. On inclusion of a patient into randomised treatment the local investigator allocated each participant the lowest available number. The block size was withheld from the investigators.

Statistical methods, sample size

Non-inferiority is usually established by showing that the true treatment difference is likely to be smaller than a prespecified non-inferiority margin that separates clinically important from clinically negligible (acceptable) differences.15 We considered that hypericum would not be relevantly inferior to paroxetine if the true decrease in total depression score (primary outcome measure) for hypericum was not more than 2.5 points16 smaller than for paroxetine (δ = -2.5).

The study was performed with an adaptive interim analysis. This design includes options for early stopping with rejection of the null hypothesis or for fultility (boundaries α1 = 0.01 and α0 = 0.5, respectively) or for re-estimation of sample size in case of continuation.

For the change in total depression score we assessed non-inferiority of hypericum by a shifted t test using the prespecified non-inferiority margin of 2.5 points and a global one sided type I error of α = 0.025. We used Fisher's combination test17 in the final analysis, where the null hypothesis can be rejected when the product of the P values from both study parts falls below cα = 0.0038. An analogous approach consists of calculating the one sided repeated 97.5% confidence limit for the treatment difference adjusted for the interim analysis.18 If this confidence limit is completely above the non-inferiority margin δ = -2.5, hypericum would be judged to be not inferior to paroxetine.

According to applicable guidance19 we reserved the option of testing for superiority after establishing non-inferiority of hypericum. If the lower one sided 97.5% confidence limit lies above 0, hypericum can be considered superior to paroxetine. We replaced missing values by carrying the last observation forward. The primary analysis was based on the intention to treat analysis to mirror clinical practice. We also performed a per protocol analysis to demonstrate robustness of the trial result to the choice of the analysis set.19 All secondary efficacy and safety measures were analysed descriptively. For the Hamilton total score, we defined response as a decrease in total score of ≥ 50% from baseline and remission as a score ≤ 10 points at week six.

We calculated the sample size for the first stage of the study until the interim analysis by assuming equal changes in depression score in each group with a common SD of 6 points. We needed 2×50 patients to attain 90% power for a one sided P value of P1 ≤ 0.20 in the interim analysis (trend towards non-inferiority of hypericum). The interim analysis resulted in a one sided P1 = 0.084 for the primary outcome measure so that the local type I error level for the second part of the trial was determined as cα/P1 = 0.045. Assuming a common SD of 6 points and equal means in both groups, we needed 2×75 patients to attain a power of 80% for the second stage of the trial, resulting in a total sample size of 2×125 patients.

Results

Participants

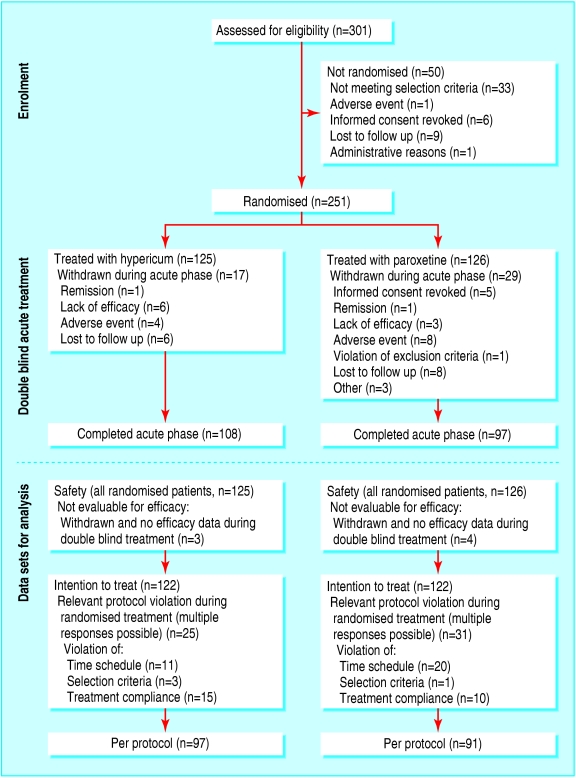

Between May 2000 and July 2003, we assessed 301 white patients and randomised and treated 251 (125 to hypericum and 126 to paroxetine). Figure 1 shows reasons for non-randomisation, premature termination, or exclusion. We did not exclude any patients because we thought they were at increased risk of suicide. Among the patients who were not randomised, two were withdrawn because they responded to placebo during the run-in period. All decisions regarding patient eligibility were made before code breaking.

Fig 1.

Flow of patients and datasets for analysis

Baseline demographic and clinical measures were comparable in both groups (table 1). Mean age and average duration of the current episode, however, were higher in the hypericum group. The baseline total depression scores ranged from 22 (minimum required) to 34 in both groups. In each group more than half of the patients had a total score ≥ 25 and were thus severely depressed.20

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline (intention to treat analysis; figures are means (SD); medians unless stated otherwise)

| Hypericum (n=122) | Paroxetine (n=122) | |

|---|---|---|

| No (%) of women | 85 (70) | 83 (68) |

| Age (years) | 49.0 (11.0); 51.5 | 45.5 (11.5); 48.0 |

| No (%) with recurrent depression | 50 (41) | 49 (40) |

| Duration of current episode (days) | 160 (109); 148 | 127 (81); 106 |

| HAMD total score* | 25.5 (2.7); 25.0 | 25.5 (2.9); 25.0 |

| No (%) with HAMD total score ≥25 | 69 (57) | 67 (55) |

| MADRS total score† | 29.9 (5.0); 29.0 | 29.4 (4.9); 29.0 |

| Beck depression inventory‡ | 26.3 (8.5); 26.0 | 25.6 (8.0); 24.5 |

| No (%) markedly or severelly ill§ | 87 (71) | 84 (69) |

HAMD=Hamilton depression scale; MADRS=Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale.

Theoretical range 0-52.

Theoretical range 0-60.

Theoretical range 0-63; 119 in hypericum group, 120 in paroxetine group.

According to clinical global impressions score.

Investigational treatment

After two weeks of randomised treatment, 69/122 patients in the hypericum group (57%) and 58/122 in the paroxetine group (48%) were switched to the higher doses. We assessed compliance with treatment by counting tablets; it was 96% (SD 7%) for hypericum and 98% (SD 10%) for paroxetine.

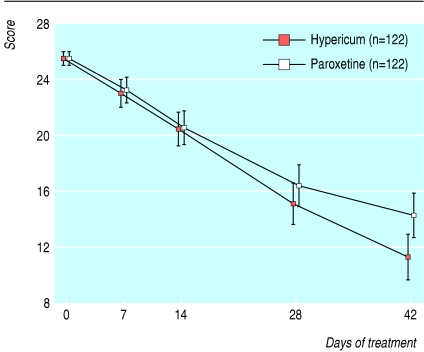

Figure 2 shows the total Hamilton depression scores over time. Between baseline and day 42 scores decreased by an average of 14.4 (SD 8.8) points (corresponding to 57% (SD 34%) of the baseline value) for hypericum and by 11.4 (SD 8.6) points (45% (SD 34%)) for paroxetine (lower one sided repeated 97.5% confidence limit adjusted for the interim analysis18 for the difference hypericum-paroxetine was 1.5 points). In the per protocol analysis the decreases in scores during treatment were 14.6 (SD 9.0) points for hypericum and 12.0 (SD 8.5) points for paroxetine (lower confidence limit 0.7 points). Hence, the lower confidence limits not only exceeded the non-inferiority margin of -2.5 points but also the value 0, showing that hypericum is statistically superior to paroxetine at the one sided 2.5% level.

Fig 2.

Total Hamilton depression scores over time (intention to treat analysis, means and 95% confidence intervals)

According to mean change in depression score from baseline, hypericum was descriptively superior to paroxetine in 11 of those 13 centres that had two or more patients in each group. At the end of the acute treatment phase 86/122 patients (71%) in the hypericum group and 73/122 (60%) in the paroxetine group responded to treatment (P = 0.08; χ2 test), and 61/122 (50%) and 43/122 patients (35%) showed remission (P = 0.02).

A subgroup analysis showed that patients who were switched to 1800 mg/day hypericum or 40 mg/day paroxetine because of lack of efficacy during the first two weeks of randomised treatment showed marked decreases in total depression score during weeks three to six. By the end of the double blind treatment period (day 42) we observed a substantial amelioration of symptoms compared with baseline in patients with or without an increase in drug dose in both treatment groups (mean (SD) decrease in total score from baseline to day 42: hypericum 900 mg/day 16.6 (7.5) points, hypericum 1800 mg/day 12.6 (9.3) points, paroxetine 20 mg/day 11.0 (8.9) points, paroxetine 40 mg/day 11.8 (8.1) points).

Table 2 shows the main results for selected secondary measures. For all standardised psychiatric scales we found differences between treatment groups in favour of hypericum, confirming our previous results.

Table 2.

Secondary measures (intention to treat analysis; figures are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise)

| Hypericum (n=122) | Paroxetine (n=122) | Difference (hypericum minus paroxetine) (95% CI), P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change from baseline to day 42: | |||

| MADRS (mean (SD); median) | 16.4 (10.7); 17.0 | 12.6 (10.6); 14.0 | 3.8 (1.1 to 6.5), 0.01* |

| BDI (mean (SD); median)† | 10.2 (10.3); 9.0 | 7.0 (9.3); 5.5 | 3.2 (0.7 to 5.7), 0.01* |

| Scores by day 42: | |||

| Clinical global impressions: | |||

| Item 1 improved by ≥2 categories | 71 (58) | 52 (43) | 16 (3 to 28), 0.02‡ |

| Item 2 much or very much improved | 83 (68) | 70 (57) | 11 (-1 to 23), 0.09‡ |

| Item 3 marked therapeutic effect | 49 (40) | 36 (30) | 11 (-1 to 23), 0.08‡ |

| Global efficacy self rating very good or good | 65 (53) | 55 (45) | 8 (-4 to 21), 0.20‡ |

MADRS=Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale; BDI=Beck depression inventory.

t test for difference (calculated for pooled data from both study stages).

119 in hypericum group, 120 in paroxetine group.

χ2 test for difference (calculated for pooled data from both study stages).

Safety and tolerability

During the acute treatment phase 69/125 patients randomised to hypericum (55%) reported 172 adverse events and 96/126 treated with paroxetine (76%) reported 269 adverse events. The incidences were 0.035 adverse events per day of exposure (0.029 at 900 mg/day and 0.039 at 1800 mg/day) for hypericum and 0.060 (0.062 at 20 mg/day and 0.059 at 40 mg/day) for paroxetine. Based on the rate ratio, the incidence of adverse events in the paroxetine group was 1.72 (95% confidence interval21 1.42 to 2.10) of the rate observed for hypericum. The highest incidence was found for gastrointestinal disorders (59 events in 42 patients in the hypericum group and 106 events in 67 patients in the paroxetine group), followed by nervous system disorders (35 events in 29 patients and 61 events in 43 patients, respectively). Table 3 shows adverse events that occurred in at least 10 patients in one group. Two serious adverse events occurred in the hypericum group (psychic decompensation attributable to social problems; hypertensive crisis); both were thought to be unrelated to hypericum—that is, a cause other than the administration of hypericum was evident.

Table 3.

Adverse events that occurred in at least 10 patients in one group (safety analysis set; figures are numbers (percentages) of patients

| Hypericum (n=125) | Paroxetine (n=126) | |

|---|---|---|

| Upper abdominal pain | 12 (9.6) | 9 (7.1) |

| Diarrhoea | 12 (9.6) | 23 (18.3) |

| Dry mouth | 16 (12.8) | 35 (27.8) |

| Nausea | 9 (7.2) | 21 (16.7) |

| Fatigue | 14 (11.2) | 16 (12.7) |

| Dizziness | 9 (7.2) | 24 (19.1) |

| Headache | 13 (10.4) | 14 (11.1) |

| Sleep disorder | 5 (4.0) | 10 (7.9) |

| Increased sweating | 9 (7.2) | 13 (10.3) |

Discussion

Principal findings

We have shown that hypericum extract WS 5570 is at least as effective as paroxetine over six weeks of acute treatment in outpatients with moderate or severe unipolar major depression. This finding was stable across several validated investigator and self rating scales and across the participating centres as well as in different analysis datasets (including or excluding patients with major protocol violations). The average advantage of 3 points for the decrease in total Hamilton depression score from baseline underlines the clinical relevance of the observed effect,16 as do the responder rates of 70% v 60% and the remission rates of 50% v 35% for hypericum and paroxetine, respectively. The results thus indicate that in a group of patients in whom the appropriateness of hypericum extract was previously disputed, the antidepressant efficacy of the herbal drug is at least comparable with the effect of one of the leading synthetic antidepressants. In patients with insufficient response to the initial (lower) dose an increase in dose after two weeks was beneficial.

What is already known on this topic

Hypericum extract is effective in the acute treatment of patients with mild to moderate depression

The only randomised controlled trial to date in patients with severe depression was underpowered

What this study adds

This double blind randomised clinical trial showed that hypericum extract WS 5570 is at least as effective as paroxetine in ameliorating the symptoms of moderately or severely depressed patients

It is important to note that for both drugs the higher dose was not associated with a relevant increase in adverse events. In particular, none of the patients exposed to hypericum 1800 mg/day for four weeks reported any photosensitivity reactions that have previously been reported.22,23

Strengths and weaknesses

These results contribute to the assessment of the antidepressant effect of hypericum extract in moderately and severely depressed patients in whom only limited evidence exists. Non-inferiority trials of hypericum extract against synthetic antidepressants have been criticised for using doses mostly in the lower therapeutic range of the active comparators.24 This criticism does not apply to our trial, which included a mandatory dose increase in patients with insufficient response after two weeks of treatment. For paroxetine, 40 mg/day correspond to the established use of the drug in clinical trials and daily practice.12 The trial's assay sensitivity is supported by the observed treatment effect for paroxetine which was in line with previously published data from trials against placebo and synthetic antidepressants.10 Another indicator of a pharmacological effect is that in both study groups a (single blind) dose increase in initial non-responders was followed by a substantial decrease in depression score that was comparable with the effect observed in those patients who were adequately treated with the initial (lower) dose. A placebo control could not be used in this group of predominantly severely depressed patients for ethical reasons, particularly as comedication with benzodiazepines was not permitted. For the same reason we had to refrain from including patients at high risk of suicide. As we did not actually withdraw any patient because of increased risk of suicide, however, this restriction does not adversely affect the external validity of our data.

Implications for clinicians

Our results support the use of hypericum extract WS 5570 as an alternative to standard antidepressants in moderate to severe depression, especially as it is well tolerated.7 As in any effective antidepressant, potential interactions with other drugs deserve clinical attention.7

The convincing results for hypericum extract WS 5570 observed in this trial deserve independent confirmation by other research. We are assessing efficacy in long term treatment, for which the drug can be an interesting option because of its favourable ratio between efficacy and tolerability, in the ongoing continuation phase.

We thank the investigators and patients, St Klement for project management, T Konstantinowicz for the data analysis, T Utz for project assistance, and A Völp for help with the manuscript.

Contributors: AS and RK conceived the study. AD conceived the study, and participated in its design and coordination. MK participated in the design of the study and was responsible for the analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. AD and MK are guarantors.

Funding: Dr Willmar Schwabe Pharmaceuticals, manufacturer of WS 5570.

Competing interests: AS has received consultancy fees from Dr Willmar Schwabe Pharmaceuticals. RK is head of a contract research organisation (IMEREM), which is engaged in several clinical trials of hypericum extract for different pharmaceutical companies. AD and MK are employees of Dr Willmar Schwabe Pharmaceuticals.

Ethical approval: The protocol was approved by the participating centres' appropriate independent ethics committees.

References

- 1.Linde K, Mulrow CD. St John's wort for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(4): CD000448. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Harrer G, Hübner WD, Podzuweit H. Effectiveness and tolerance of the hypericum extract LI 160 compared to maprotiline: a multicenter double-blind study. J Geriatric Psychiatry Neurol 1994;7(suppl 1): S24-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Philipp M, Kohnen R, Hiller KO. Hypericum extract versus imipramine or placebo in patients with moderate depression: randomised multicentre study of treatment for eight weeks. BMJ 1999;319: 1534-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vorbach EU, Hübner WD, Arnoldt KH. Effectiveness and tolerance of the hypericum extract LI 160 in comparison with imipramine: randomized double-blind study with 135 outpatients. J Geriatric Psychiatry Neurol 1994;7(suppl 1): S19-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wheatley D. LI 160, an extract of St. John's wort, versus amitriptyline in mildly to moderately depressed outpatients—a controlled 6-week clinical trial. Pharmacopsychiatry 1997;30(suppl 2): 77-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrer G, Schmidt U, Kuhn U, Biller A. Äquivalenzvergleich Johanniskrautextrakt LoHyp-57 versus Fluoxetin. Arzneimittel-Forschung 1998;49: 3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Izzo AA. Drug interactions with St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum): a review of the clinical evidence. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004;42: 139-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winkler D, Tauscher J, Kasper S. Maintenance treatment in depression. The role of pharmacological and psychological treatment. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2002;15: 63-8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lecrubier Y, Clerc G, Didi R, Kieser M. Efficacy of St. John's wort extract WS 5570 in major depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159: 1361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourin M, Chue P, Guillon Y. Paroxetine: a review. CNS Drug Rev 2001;7: 25-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Preskorn SH. Comparison of the tolerability of bupropion, fluoxetine, imipramine, nefazodone, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56(suppl 6): 12-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunner DL, Dunbar GC. Optimal dose regimen for paroxetine. J Clin Psychiatry 1992;53(suppl): 21-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kupfer DJ. Lessons to be learned from long-term treatment of affective disorders: potential utility in panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1991;52(suppl); 12-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The miniinternational neuropsychiatric interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59(suppl 20): S22-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones B, Jarvis P, Lewis JA, Ebbutt AF. Trials to assess equivalence: the importance of rigorous methods. BMJ 1996;313: 36-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montgomery SA. Clinically relevant effect sizes in depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology 1994;4: 283-4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauer P, Köhne K. Evaluation of experiments with adaptive interim analyses. Biometrics 1994;50: 1029-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brannath W, Posch M, Bauer P. Recursive combination tests. J Am Stat Assoc 2002;97: 236-44. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products. Points to consider on switching between superiority and non-inferiority. London: European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, 2000.

- 20.Paykel ES. The classification of depression. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1983;15(suppl 2): 155-9S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ederer F, Mantel N. Confidence limits on the ratio of two Poisson variables. Am J Epidemiol 1974;100: 165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golsch S, Vocks E, Rakoski J, Brockow K, Ring J. Reversible Erhöhung der Photosensitivität im UV-B-Bereich durch Johanniskrautextrakt-Präparate. Hautarzt 1996;48: 249-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulz V. Incidence and clinical relevance of the interactions and side effects of Hypericum preparations. Phytomedicine 2001;8: 152-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hypericum Depression Trial Study Group. Effect of Hypericum perforatum (St. John's wort) in major depressive disorder. JAMA 2002;287: 1807-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]