Health can be defined as optimum physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and intellectual health. Health promotion is the science or art of helping people change their lifestyle to move towards a state of optimal health. Lifestyle change can be facilitated through a combination of efforts to increase awareness, change behaviour, and create environments that support good health practices.

Need for health promotion

There are five main reasons for a particular health promotion focus on young people.

Health behaviours in youth continue into adult life

One of the most compelling arguments for a focus on adolescent health is that adolescence is a time when new health behaviours are laid down—behaviours that track into adulthood and will influence health and morbidity throughout life. Health behaviours in childhood are dominated by parental instruction and shared family values. During adolescence young people begin to explore alternative or “adult” health behaviours, including smoking, drinking alcohol, drug misuse, violence, and sexual intimacy. The continuity of these behaviours into adulthood is well documented.

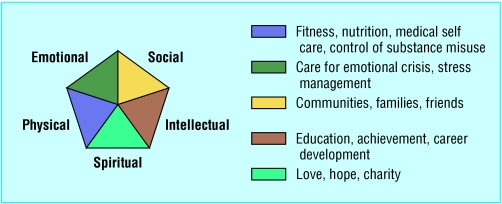

Figure 1.

Domains for health promotion. Adapted from O'Donnell MP. American Journal of Health Promotion 19893(3) 510292073

Health behaviours relating to exercise and food are also laid down in adolescence and track into adult life. Adolescent obesity predicts adult obesity, which is strongly and independently predictive of cardiovascular risk, and cardiovascular risk in young adulthood is highly related to the degree of adiposity as early as age 13 years. Evidence also shows that health in adolescence can have a considerable impact on the development of adult conditions. This evidence challenges earlier notions that adolescents moving into adulthood “grow out of” health risk behaviours and mental health problems.

Table 1.

Major health promotion areas in adolescence

| • Health risk behaviours (smoking, alcohol use, drug misuse, sexual health, and risk taking) |

| • Parent-adolescent communication |

| • Depression and mental health |

| • Violence |

| • Physical activity, nutrition, and obesity |

| • Health inequalities and social exclusion |

Immediate effects of adolescent health behaviours

Adolescent health behaviours have a direct effect on immediate as well as long term health outcomes and quality of life—for example, taking exercise, engaging in risky sexual behaviour (resulting in sexually transmitted infections or teenage pregnancy), and using the roads safely.

Worrying trends in morbidity and mortality

Adolescent mortality and morbidity show worrying trends in national priority areas, such as mental health (for example, male suicide rates), sexual health (teenage pregnancies), and cardiovascular risk (such as obesity and diabetes). Earlier engagement in sexual activity, high rates of teenage pregnancy, and the threat of HIV have similarly focused attention on adolescents. Given the evidence on the continuity of health risk behaviours in adolescence into adulthood, morbidity trends in adolescence argue strongly for urgent attention to adolescents' health and for the development of targeted, adolescent specific interventions.

Figure 2.

The website Teenage Health Freak (www.teenagehealthfreak.org) promotes health in a user friendly way to teenagers

Developmental issues

Dynamic and continued development in every aspect of a young person's life during adolescence means that young people have distinct needs in terms of delivery of health promotion messages.

Prevalence of regular smoking rises from 1% at age 11 years to 24% at 15 years, and over 90% of adult smokers began smoking as teenagers; similarly, few people start experimenting with alcohol and drugs after their teenage years

Improvements in mortality and morbidity in early childhood have not been matched in adolescence

In early adolescence, concrete thinking predominates, with young people generally able to understand only linear “concrete” relations between cause and effect. In this very literal context, messages that smoking causes lung cancer can be rejected as irrelevant, as they know that their friends who smoke do not have lung cancer.

Table 2.

Implications of adolescent development for health promotion in adolescence

| Psychological development | Social development | Implications for health promotion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early adolescence |

Concrete thinking but grasp of moral concepts; assessment and adjustment of body image |

Realising difference from parents; start of strong peer group; start of health risk behaviours |

Start health promotion messages, using concrete motivators; focus on “here and now”; use peer educators or role models; current physical health can be important motivator |

| Mid-adolescence |

Abstract thinking develops, mainly in relation to others (self is “bullet proof”) |

Increasing autonomy (away from parents) |

Target health promotion messages as for early adolescence; specifically address issues of risk to self as well as others |

| Late adolescence | Complex abstract thought and further development of identity and body image | Social autonomy; splitting of peer group into smaller groups and couples | Health promotion messages can address many possible outcomes of an action; targeting of messages at partners and close friends |

Clustering of health risk

Health risk behaviours cluster in adolescence, meaning that those who smoke are also more likely to drink alcohol and take drugs. They are also more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviour and be the victims or perpetrators of violence. This is because many health problems in adolescence have important risk factors in common. Academic failure and dropping out of school (rarely attending) are associated with the development of antisocial behaviour, higher rates of substance misuse, tobacco use, and emotional problems. Similarly, the young person's mental health and patterns of family attachment are strongly associated with many important health outcomes and other established risk factors.

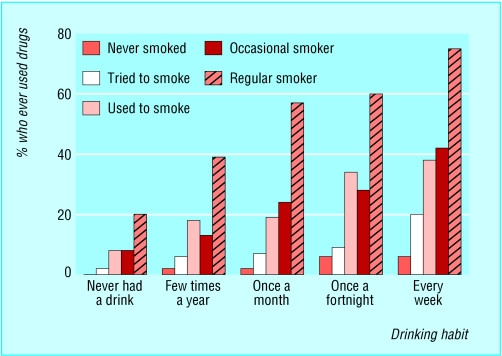

Figure 3.

Drug use by smoking behaviour and usual drinking frequency among 11-15 year olds, England, 1998. Adapted from data from Office for National Statistics (www.ons.gov.uk)

Settings for health promotion

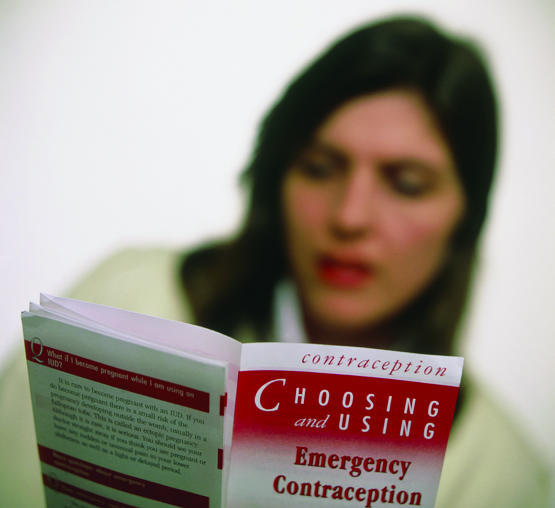

The main current strategic approaches to health promotion for adolescents have three main emphases. The first, and by far the most effective, is health promotion by society as a whole on behalf of adolescents—for example, banning cigarette advertising and making emergency contraception available over the counter.

Figure 4.

Promoting health to society as a whole (for example, making emergency contraception available over the counter) is more effective than simply urging adolescents to behave healthily

The second is health promotion by professionals with a “health education” interest, exhorting adolescents to behave in healthy ways—for example, not to smoke, to use contraception, and to eat a balanced diet. These individual approaches are not effective. The third approach is to improve young people's social abilities. Evidence exists that improving these abilities so that young people can choose whether to accept or reject certain courses of behaviour—for example, reject a lift home by a drunken boyfriend—is also effective in enabling young people to make independent choices about individual health related behaviours. It may also improve young people's self esteem.

Table 3.

Effective health promotion strategies

| • Strategies should be on behalf of adolescents rather than directed at adolescents |

| • Interventions for adolescents should be simultaneous at government, community, and local level |

| • Interventions should focus on increasing adolescents' overall self esteem and self empowerment rather than on single health issues |

| • Health professionals should act as advocates on behalf of young people and as providers to young people and their carers of the most relevant and up to date evidence based information; they should use methods and language deemed appropriate by the adolescents themselves |

However, a considerable body of evidence suggests that the most effective health promotion intervention for young people would be to improve the socioeconomic circumstances in which young people are raised and to create greater socioeconomic equality in the population as a whole. Good evidence shows also that health promotion interventions at society level on behalf of adolescents (for example, increasing the price of cigarettes and banning cigarette advertising) are far more effective than health education messages directed at adolescents (for example, “don't smoke”).

Health promotion messages should begin in early adolescence, as the key risk periods for starting smoking, taking drugs, and taking sexual risks are before age 14. In this early stage, health promotion messages should focus on the “here and now” risk rather than risks in adult life

Interventions can be delivered at various levels: the individual level, the family level, the school level, the community level, and the national level.

Table 4.

Levels at which interventions can be delivered

| Individual level—Peer interventions, including peer education; youth recreation programmes; and mentoring programmes |

| Family level—Parent training and family interventions |

| School level—Single issue, curriculum based education and “whole school” organisation and behaviour management interventions |

| Community level—Local environmental change (such as policing policy, safety issues) |

| National level—Health service reorganisation, employment and training, law and policing changes, social marketing, and socioeconomic change |

Resilience

Recognising that adolescents often engage in more than one risky behaviour and that these behaviours often have common underlying predisposing factors (such as poor socioeconomic circumstances or poor mental health), evidence is growing that effective health promotion interventions for a specific risk or protective factor are both highly effective and also likely to have direct effects on a range of health outcomes.

Table 5.

Identified risk and protective factors for adolescent health behaviours*

| Behaviour | Risk factors | Protective factors |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking |

Depression and other mental health problems; alcohol use; disconnectedness from school or family; difficulty talking with parents; minority ethnicity; low school achievement; peer smoking |

Family connectedness; perceived healthiness; higher parental expectations; low prevalence of smoking in school |

| Alcohol and drug misuse |

Depression and other mental health problems; low self esteem; easy family access to alcohol; working outside school; difficulty talking with parents; risk factors for transition from occasional to regular substance misuse (smoking, availability of substances, peer use, other risk behaviours) |

Connectedness with school and family; religious affiliation |

| Teenage pregnancy |

Deprivation; city residence; low educational expectations; lack of access to sexual health services; drug and alcohol use |

Connectedness with school and family; religious affiliation |

| Sexually transmitted infections | Mental health problems; substance misuse | Connectedness with school and family; religious affiliation |

Adapted from McIntosh N, Helms P, Smyth R, eds. Forfar and Arneil's textbook of paediatrics. 6th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2003: 1757-68

Interventions on bullying and emotional wellbeing covering whole schools, for example, are highly effective in reducing other problems, such as smoking and drug misuse among young people.

Role of individual health workers

Despite the low efficacy of most health promotion messages at individual level, health professionals do have a role in health promotion in their clinical interactions with young people. Brief health promotion discussions about smoking during routine general practice visits can reduce smoking rates, although messages are more effective if targeted at patients who are contemplating change. The “stages of change” model of behaviour change suggests that “action oriented” advice for those who are not ready to change is at best unhelpful and could even entrench unhealthy behaviour.

Table 6.

Stages of change

| • Precontemplation (not yet acknowledging that there is a problem behaviour that needs to be changed) |

| • Contemplation (acknowledging a problem but not yet ready (or sure of wanting) to make change) |

| • Preparation/determination (getting ready to change) |

| • Action/willpower (changing behaviour) |

| • Maintenance (maintaining behaviour change) |

| • Relapse (reverting to older behaviour and abandoning new changes) |

Patients themselves report that health promotion advice from their doctor is best received if it takes account of their receptiveness, is conveyed in a respectful tone, avoids preaching, shows support and caring, and shows understanding of them as unique individuals.

When teenagers are seen in primary care, particular areas for health promotion are sexual health, smoking, and drug misuse. Most young people who experiment with drugs do not consult their doctor, and most doctors know less about illegal drugs than young people. Evidence from randomised trials suggests, however, that providing young people aged 11 to 13 with information about illegal drugs delays the start of drug misuse.

Interventions on bullying and emotional wellbeing covering whole schools can be more effective at reducing smoking than single issue smoking programmes

The ABC of adolescence is edited by Russell Viner, consultant in adolescent medicine at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Trust (rviner@ich.ucl.ac.uk). The series will be published as a book in summer 2005.

The photograph is published with permission from Damien Lovegrove.

Aidan Macfarlane is consultant in public health policy and a community paediatrician fo Oxford Health Authority.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- • Toumbourou J, Patton GC, Sawyer S, Olsson C, Webb-Pullman J, Catalano R, et al. Evidence based health promotion. No 2. Adolescent health. Melbourne, Australia: Department of Human Services, 2000.

- • www.hda-online.org.uk/evidence/ (the Health Development Agency's “evidence base”—a searchable database of evidence on health promotion).

- • www.teenagehealthfreak.org and www.lifebytes.gov.uk (teenage friendly websites that provide health promotion material for young people).