Abstract

Gene therapy has become an important strategy for treatment of malignancies, but problems remains concerning the low gene transferring efficiency, poor transgene expression and limited targeting specific tumors, which have greatly hampered the clinical application of tumor gene therapy. Gallbladder cancer is characterized by rapid progress, poor prognosis, and aberrantly high expression of Survivin. In the present study, we used a human tumor‐specific Survivin promoter‐regulated oncolytic adenovirus vector carrying P53 gene, whose anti‐cancer effect has been widely confirmed, to construct a wide spectrum, specific, safe, effective gene‐viral therapy system, AdSurp‐P53. Examining expression of enhanced green fluorecent protein (EGFP), E1A and the target gene P53 in the oncolytic adenovirus system validated that Survivin promoter‐regulated oncolytic adenovirus had high proliferation activity and high P53 expression in Survivin‐positive gallbladder cancer cells. Our in vitro cytotoxicity experiment demonstrated that AdSurp‐P53 possessed a stronger cytotoxic effect against gallbladder cancer cells and hepatic cancer cells. The survival rate of EH‐GB1 cells was lower than 40% after infection of AdSurp‐P53 at multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 1 pfu/cell, while the rate was higher than 90% after infection of Ad‐P53 at the same MOI, demonstrating that AdSurp‐P53 has a potent cytotoxicity against EH‐GB1 cells. The tumor growth was greatly inhibited in nude mice bearing EH‐GB1 xenografts when the total dose of AdSurp‐P53 was 1 × 109 pfu, and terminal dUTP nick end‐labeling (TUNEL) revealed that the apoptotic rate of cancer cells was (33.4 ± 8.4)%. This oncolytic adenovirus system overcomes the long‐standing shortcomings of gene therapy: poor transgene expression and targeting of only specific tumors, with its therapeutic effect better than the traditional Ad‐P53 therapy regimen already on market; our system might be used for patients with advanced gallbladder cancer and other cancers, who are not sensitive to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or who lost their chance for surgical treatment.

Keywords: Gallbladder cancer, Oncolytic adenovirus, Gene therapy, Tumor-specific promoter

Highlights

Survivin promoter‐regulated oncolytic adenovirus AdSurp‐P53 is recombined.

The oncolytic adenovirus has a high proliferation activity in gallbladder cancer.

The oncolytic adenovirus mediates high P53 expression in gallbladder cancer cells.

AdSurp‐P53 possesses a stronger cytotoxic effect against gallbladder cancer cells.

AdSurp‐P53 inhibits xenograft tumor growth in nude mice by inducing cell apoptosis.

1. Introduction

Gallbladder cancer is characterized by rapid progress and responses poorly to routine treatment. Gene therapy has become an important treatment for malignancies. Up to Jun 2011, a total of 1714 gene therapy clinical trials have been tested, and 1107 (64.6%) are for tumor treatment, with most of them via adenovirus vector (24.2%) (J. Gene Med., 2011). The E1‐defective replication‐incompetent adenoviral vectors used earlier are incapable of replication; the safety is guaranteed but the infection of each tumor cell is impossible, which limited its therapeutic effect. The world first anti‐tumor gene therapeutic drug, recombinant human P53 adenovirus (Ad‐P53), which was approved by the State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA) of China in 2004, belongs to this replication‐incompetent adenoviral vector (Lu et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2010; Peng, 2005). More recently, the conditionally replicative adenovirus (CRAd), which can replicate specifically in tumor cells and can therefore infect, kill more tumor cells (also called oncolytic adenovirus) has been developed; the early representative of oncolytic adenovirus was Onyx‐015 (Bagheri et al., 2011; Hemminki et al., 2011; He et al., 2009; Opyrchal et al., 2009). H101 is the first commercialized oncolytic adenoviral product approved by SFDA; it is mainly aimed to treat head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and other tumors (Huang et al., 2009; Song et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2004). Great improvement has been made in preclinical research of anti‐tumor gene therapy, but the clinical researches are relatively scarce. A decade long clinical research has demonstrated that the anti‐tumor gene therapy is safe enough but has a low anti‐tumor efficiency, mainly due to the low gene transferring efficiency, poor transgene expression and poor targeting of tumor cells (Rubanyi, 2001).

Up to now, many efforts have been made to improve the vector system and to optimize anti‐tumor genes. We combined the advantages of oncolytic adenovirus with gene therapy and proposed the strategy of “targeting gene‐viral therapy” (Su et al., 2006, 2004, 2006), in which the tumor‐specific oncolytic adenovirus is used as vector and the tumor suppressor gene is inserted into viral genome, so as to fully achieve the dual functions of gene therapy and virotherapy. Due to the high diffusion, high transfection and specific replication in tumor cells, the virus can replicate and lyse cancer cells; meanwhile, the copies of tumor suppressor gene increase with virus replication, which results in high expression of tumor suppressor gene and more potent anti‐tumor effect. A number of tissue‐ or cell‐specific promoters have been identified and used for oncolytic adenovirus, including the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) promoter targeting colorectal cancer and lung cancer, Mucin‐like glycoprotein episialin (MUC1) promoter targeting breast cancer, E2F‐transcription factor promoter targeting retinoblastoma (Rb)‐defective cancer, alpha‐fetoprotein (AFP) promoter targeting hepatic carcinoma, Tyr promoter targeting melanoma, and Epstein–Barr virus promoter targeting nasopharyngeal cancer (Osaki et al., 1994; Chen et al., 1995; Kurihara et al., 2000; Parr et al., 1997; Johnson et al., 2002; Tsukuda et al., 2002; Hallenbeck et al., 1999; Ohashi et al., 2001; Rodriguez et al., 1997; Peng et al., 2001). Researches have shown that the adenoviral replication regulated by the above mentioned promoters can obtain relatively specific tumor targeting effect.

Optimization of tumor suppresser gene is an important strategy to improve the efficacy of gene therapy. As the earliest discovered tumor suppresser gene, P53 possesses well‐known advantages and safety in its anti‐tumor characteristics, which has been verified in commercialized product (Ad‐P53). In recent years, a great number of researches have been done on P53 and a series of important articles have been published, which have described the novel anti‐tumor mechanisms of P53. The restoration of P53 function can kill tumor cells via apoptosis, cell aging, activating immune system of the host, etc. Even at the advanced stage, restoration of damaged P53 pathway can stop tumor growth (Lane et al., 2010; Budanov and Karin, 2008; Martins et al., 2006; Feldser et al., 2010; Ventura et al., 2007). The novel findings have suggested a greater role of P53 in clinical application of gene therapy.

Our previous research found that Survivin is highly expressed in most human tumors. Survivin, an important member of inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs), can inhibit cell apoptosis by binding with caspase‐9 or by interacting with NF‐κB (Garcia‐Saez et al., 2011; Rao et al., 2011). Survivin has a high frequency in various human tumors, and it is closely related to the high proliferation of tumor cells, high metastatic capability, and resistance to chemoradiotherapy (Rödel et al., 2011; Ryan et al., 2009), which makes it an ideal target for tumor therapy. In the present study, we constructed a Survivin promoter‐regulated oncolytic adenovirus vector carrying tumor suppresser gene P53, and to study its in vitro and in vivo replication activity and its anti‐tumor efficacy, hoping to establish a wide spectrum, specific, safe and highly effective anti‐tumor gene therapy strategy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

Normal fibroblasts MRC‐5, BJ were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, 20108, USA). Gallbladder cancer cell line EH‐GB1 was kept by Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital; hepatic carcinoma cell line BEL‐7404 cells were purchased from Shanghai Institute for Biological Science, Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured with Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium(GIBCO) containing 100 ml/L fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 kU/L penicillin, and 100 mg/L streptomycin at 37 °C and in an atmosphere of containing 5% CO2.

2.2. Expression of Survivin in cells

The above mentioned cell lines were cultured in 6‐well plate and collected during exponential phase. The total RNAs were extracted using TriZol Reagent kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) was used to detect Survivin expression. The primers were designed according to the Survivin cDNA sequence; the forward primer sequence was 5′‐cgg aat tca cca tgg gtg ccc cga cg‐3′, the reverse primer sequence was 5′‐gaa gat ctt caa tcc atg gca gcc ag‐3′. Survivin cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript™ One‐Step RT‐PCR with Platnum® Taq kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instruction, with the following amplification condition: 50 °C 30 min; 94 °C 2 min; 94 °C 30 s, 60 °C 30 s, 72 °C 60 s, 30 cycles; 72 °C 2 min, the amplified fragment was 450 bp. Glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was taken as the internal control, with the primers being AT094: 5′‐accacagtccatgccatcac‐3′, AT095: 5′‐tccaccaccctgttgcttgta‐3′.

2.3. Cloning of Survivin promoter and verification of its activity

According to the forward 5′‐untranslated region (UTR) sequence, the core promoter sequence primer was designed: the forward primer sequence 5′‐cgGCTAGCcatagaaccagag‐3′ (containing NheI), the reverse primer sequence was 5′‐gaAGATCTgccgccgccgccacct‐3′ (containing BglII); the amplified fragment was 1 kb. HepG2 cell genome DNA was extracted and used as template to amplify the Survivin promoter, and the product was cloned into NheI + BglII sites of pGL3‐Basic plasmid to construct pGL3‐hSurp.

Cells were routinely planted in 24‐well plate, with each well containing 1 × 105 cells. The plasmids, pGL3‐Basic, pGL3‐Control, and pGL3‐hSurp (each 200 ng) (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) were separately co‐transfected with pRL‐TK (20 ng) via Effectene® Transfection Reagent (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA). Cells were cultured for 48 h and lysed, and half of the cell lysates were collected according to the instructions of Dual‐Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). The luciferase activity was determined by LB‐9506 Luminometer (Berthold Technologies). The experiments were done independently three times and the data were presented as ‘mean ± standard deviation’. The luciferase activities of pGL3‐basic and pGL3‐hSurp were normalized with that of pGL3‐Control in each cell line and shown as percentages.

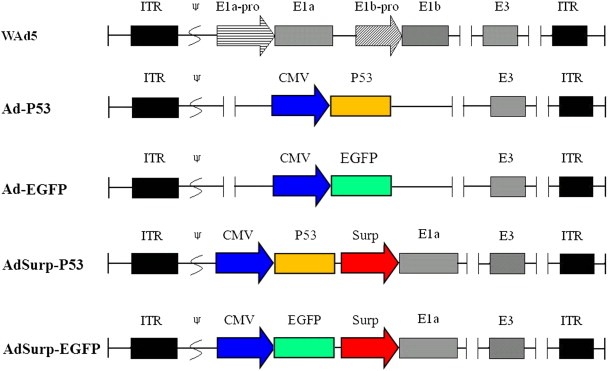

2.4. Construction of adenovirus vectors

The Survivin promoter was digested from pGL3‐hSurp and inserted into the upstream of Ela gene of pXC1 plasmid, and then the complete expression cassette of Ela was released and inserted into previously constructed plasmid pCA13‐P53 to construct pSurp‐P53. pSurp‐P53 was co‐transfected with pBHGE3 (an E1‐deleted backbone plasmid of type 5 adenoviral right arm) (Microbix Biosystem Inc.) into 293 cells by Effectene® Transfection Reagent (QIAGEN Inc.). Ten days later, virus plaque appeared and was collected; adenoviral DNA was abstracted using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN Inc.) following the manufacturer's instruction, and was confirmed by PCR analysis using the forward and reverse primers of E1 region (sense 59927: 5′‐GTG TAT TTA TAC CCG GTG AG‐3′, anti‐sense 59928: 5′‐TGG AAG ATT ATC AGC CAG TAC‐3′). The confirmed recombinant adenovirus was named AdSurp‐P53. Whilst, the control adenoviruses Ad‐P53, Ad‐EGFP and AdSurp‐EGFP were constructed from the plasmids pCA13‐P53, pCA13‐EGFP and pSurp‐EGFP, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the recombinant adenoviruses. Compared with the wild type of adenovirus, the expression cassette of P53 or EGFP was inserted into adenoviral genome to replace E1 region and generated the recombinant adenoviruses Ad‐P53 or Ad‐EGFP. The Survivin promoter was used to regulate the E1a gene, and the expression cassette of P53 or EGFP was inserted into adenoviral E1 region upstream of E1a gene, then generated the recombinant oncolytic adenoviruses AdSurp‐P53 or AdSurp‐EGFP. ITR: inverted terminal repeats; ψ: adenovirus 5 packaging signal; E1a‐pro: the wild type of E1a promoter; E1b‐pro: the wild type of E1b promoter, including E1b‐55KD and E1b‐19KD; CMV: cytomegalovirus promoter; Surp: Survivin promoter.

2.5. Western blotting analysis of E1A and P53

Cells were counted and seeded on 24‐well plate at a density of 5 × 104/well for 24 h. AdSurp‐EGFP, AdSurp‐P53 or Ad‐P53 was separately added to the system at an MOI of 5 pfu/cell, and Ad‐EGFP at MOIs of 5 and 20 pfu/cell. Cells were then gently shaken for 2 h; the supernatant was then discarded and 2% serum medium was added for a 48 h culture. Cells were collected and lysed with PER™ Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (PIERCE, Rockford, IL); the proteins were harvested and kept at −80 °C after quantified by BioPhotometer (Eppendorf AG).

Agarose gel electrophoresis solution (10%) was used to separate the protein at 70 V. The protein was transferred to PROTRAN® Nitrocellulose Transfer Membrane (Schleicher & Schuell Inc.) and was then blocked with blocking buffer (0.5% FBS, 50 mmol/L Tris–HCl pH7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% Tween‐20, 0.02% NaN3) for 1 h, washed with 1 × Tris buffered saline‐Tween (TBST, 50 mmol/L Tris–HCl pH7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% Tween‐20) for 3 times, each time 5 min. Then the membrane was incubated with the primary antibodies (monoclonal antibodies against adenovirus E1A and P53, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at 4 °C overnight, then washed with 1 × TBST 3 times, each time 5 min; and it was allowed to react with the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)‐goat anti‐mouse IgG antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) at room temperature for 1 h, then washed with 1 × TBST 3 times, each time 5 min. Then color development solution (LumiGLO® chemiluminescent reagent and peroxide, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) was added for visualization on X‐ray film.

2.6. Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxic effect of virus on different cell lines was examined by Cell Proliferation Kit I (MTT) (Roche Diagnostics GmbH). To determine the optimal cell concentration, cells in exponential phase were collected, counted, and were made into single cell suspension of a series of concentration gradients (from 2 × 104/ml to 2 × 105/ml). The suspensions were seeded into 96‐well plate for 24 h culture, 100 μl each well and each concentration 8 holes. After another 7 days' culture, 100 μl phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 mol/L) and 10 μl MTT labeling reagent were added to each well to achieve a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml, and was cultured for 4 h; then 100 μl/solubilization solution (10% SDS in 0.01 mol/L HCl) was added to each well, and were placed in the incubator overnight. Model 550 Microplate Reader (BIO‐RAD) was used to determine the absorbance at 570 nm, with the reference wavelength at 655 nm. Cell growth curve was plotted to confirm the optimal concentration of cells.

Next, MTT assay under different MOI values was performed. Cells in exponential phase were collected, counted, and cultured with 10% serum medium. Single cell suspensions were prepared according to the above determined optimal cell concentration. The suspensions were seeded into 96‐well plate for 24 h culture, 100 μl each well. The viruses were diluted with serum free medium and 100 μl virus were added, MOIs from 0.01 to 100 pfu/cell, each MOI value 8 holes. After another 7 days' culture, MTT assay was done as described above.

2.7. Animal experiment

Thirty healthy BALB/C nude mice, aged 4‐week old, were purchased from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center of Chinese Academy of Science. Suspensions of EH‐GB1 cells in exponential phase were injected subcutaneously in the right flank of mice, each mice receiving 100 μl cell suspension (containing 5 × 106 cells). Xenografts appeared at the injecting sites about a week after injection. Mice with too big or too small tumors were excluded and the rest 24 mice were randomly divided into 4 equal groups: AdSurp‐P53, Ad‐P53, Ad‐LacZ, and blank control groups. Mice in each group received multiple site intratumor injections of recombinant adenoviruses (2 × 108 pfu/100 μl) every other day, for 5 times. Mice in the blank control group were injected with normal saline in the same manner. The tumor volumes were determined each week after treatment using the following formula: tumor volume = maximal diameter × minimal diameter2 × 0.5.

Mice were sacrificed by aether anesthesia 31 days later after the first injection; tumor specimens were fixed with 10% formalin and were made into paraffin‐embedded sections. Streptavidin proxidase (SP) method was used to localize P53 expression in the tumor tissues; TUNEL assay was used to examine cell apoptosis. The proportions of positive cells were observed in each section under 5 high power fields.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All the data were presented as ‘mean ± standard deviation’. Paired samples t test was used for multiple comparisons; comparison between groups was done by analysis of variance (ANOVA) test using SPSS13.0 system.

3. Results

3.1. Specific activity of the Survivin promoter in tumor cells

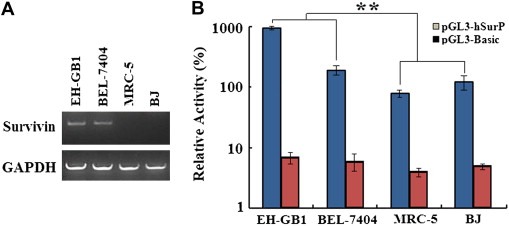

RT‐PCR confirmed that Survivin is expressed in BEL‐7404 and EH‐GB1 cells and not expressed in normal MRC‐5 and BJ cells (Figure 2A). Correspondingly, the activity of Survivin promoter in cancer cell lines was greatly higher than that in the normal cell lines (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Detection of Survivin expression and promoter activity. (A), Total RNA was extracted using TriZol reagent and Survivin mRNA was amplified by RT‐PCR. Survivin mRNA was positive in EH‐GB1 and BEL‐7404 cells but not in normal cell line MRC‐5 and BJ. (B), Luciferase reporter gene was used to detect the relative activity of Survivin promoter. The luciferase activities of pGL3‐basic and pGL3‐hSurp were normalized with that of pGL3‐Control in each cell line and shown as percentages. The Survivin promoter activities were high in EH‐GB1 and BEL‐7404 cells and low in MRC‐5 and BJ cells (**p = 0.0026).

3.2. Proliferation of tumor‐targeting adenovirus and specificity of gene expression

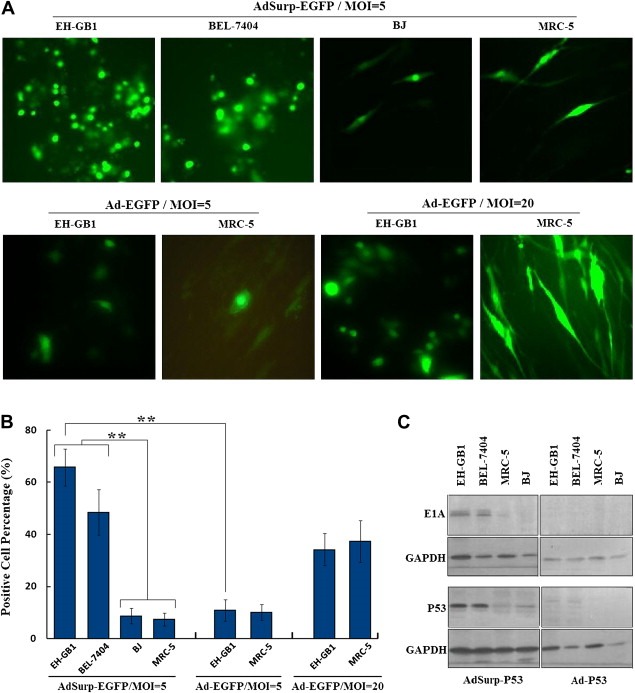

EGFP was strongly expressed in cancer cells infected with the Survivin promoter‐mediated tumor‐specific adenovirus harboring EGFP (AdSurp‐EGFP), but was only weakly expressed in normal cells after infection (p = 0.0001, Figure 3A). To prove that the specificity of expression is possibly due to the difference between cancer cells and normal cells, the E1 region‐deleted adenovirus with the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter‐driven EGFP gene (Ad‐EGFP) was used to infect EH‐GB1 and MRC‐5 cells at MOIs of 5 and 20 pfu/cell. Ad‐EGFP‐mediated expression of EGFP was enhanced with increase of MOIs both in EH‐GB1 and MRC‐5 cells. Compared with Ad‐EGFP, AdSurp‐EGFP mediated higher level of EGFP expression in EH‐GB1 cells (p = 0.0003), but there was no difference in MRC‐5 cells when infected at the same MOI of 5 pfu/cell (p = 0.3035, Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Specific proliferation of Survivin promoter‐mediated oncolytic adenovirus. (A), When MOI = 5 pfu/cell, AdSurp‐EGFP proliferated in cancer cells and resulted in high EGFP expression; whereas EGFP expression was low in BJ and MRC‐5 cells. But AdSurp‐EGFP mediated higher level of EGFP expression in cancer cells EH‐GB1 and the same level of EGFP expression in normal cells MRC‐5 when infected at the same MOI of 5 pfu/cell, original magnification × 200. (B), The EGFP‐positive cell percentage of every tested cell line was counted within 5 medium‐power fields (original magnification × 200) under microscope, and showed in histograms, **p < 0.01. (C), Western blotting analysis detected AdSurp‐P53‐mediated E1A and P53 expression in cancer cells, which was significantly higher than that mediated by Ad‐P53, and both AdSurp‐P53 and Ad‐P53 resulted in almost no expression in normal cells at MOI = 5 pfu/cell.

E1A and P53 were positively expressed in cancer cells infected with the Survivin promoter‐mediated tumor‐targeting adenovirus AdSurp‐P53, but were not or only weakly expressed in normal cells. Ad‐P53 did not expressed E1A at the indicated MOI, and expression of P53 was greatly lower than AdSurp‐P53 (Figure 3C), indicating the Survivin promoter‐mediated tumor‐targeting adenovirus specifically proliferated in the cancer cells.

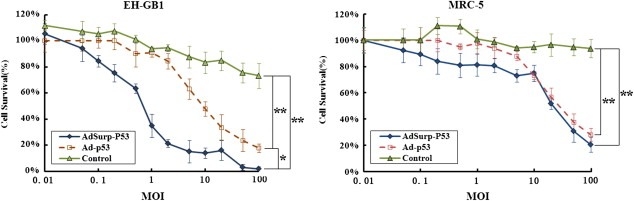

3.3. In vitro cytotoxicity of the Survivin promoter‐mediated tumor‐specific adenovirus

MTT assay determined that the optimal cell concentration was 104 cell/well, according to which the cells were seeded into 96‐well plate. We found that when MOI = 1 pfu/cell, the survival rate of EH‐GB1 cells infected with AdSurp‐P53 was less than 40%, and that of EH‐GB1 cells infected with Ad‐P53 was higher than 90%, suggesting that AdSurp‐P53 had a stronger cytotoxic effect against EH‐GB1 cells. AdSurp‐P53 and Ad‐P53 had a similar effect in normal cell line MRC‐5; when MOI = 10 pfu/cell, cells maintained a survival rate of about 80% (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cytotoxic effect of tumor‐specific AdSurp‐P53 against cancer cells. Cells were seeded into 96‐well plate at 104 cell/well and were infected with AdSurp‐P53 and Ad‐P53 when MOI = 0.01 to 100 pfu/cell; the cytotixic effects of AdSurp‐P53 and Ad‐P53 were compared on cancer cells and normal cells, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

The IC50 value of AdSurp‐P53 was 0.78 ± 0.21 pfu/cell against EH‐GB1, which was significantly different from that of Ad‐P53 (9.29 ± 2.68 pfu/cell, p = 0.0054). The IC50 values of AdSurp‐P53 and Ad‐P53 against MRC‐5 cells were 22.73 ± 6.14 pfu/cell and 29.75 ± 6.69 pfu/cell, respectively; and there was no significant difference between the two (p = 0.2512).

3.4. Anti‐tumor effects on cancer xenografts in nude mice models

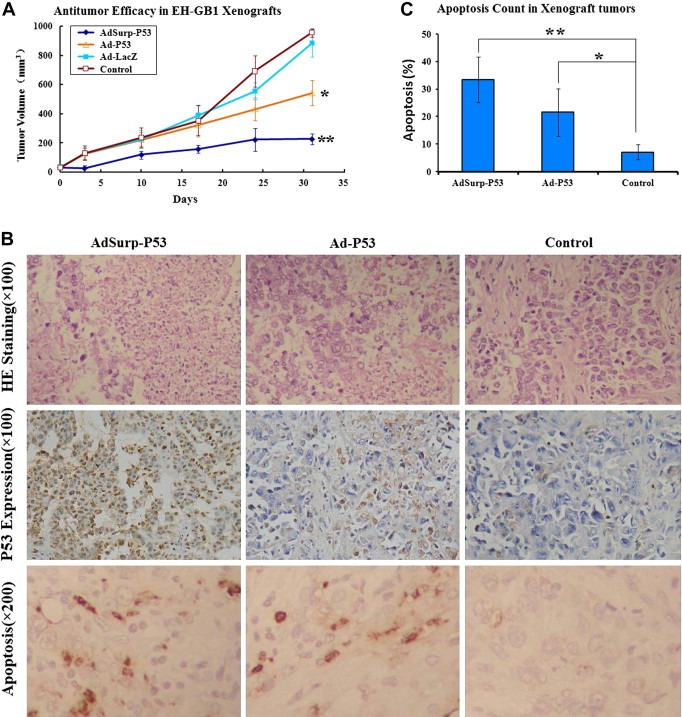

Gallbladder carcinoma cell line EH‐GB1 was implanted subcutaneously in BALB/C nude mice, which were divided into different groups on the 14th day when the diameter of the tumors reached about 5 mm. Mice were treated once every other day for 5 times, each time with a dose of 2 × 108 pfu. Seventeen days after initial treatment, AdSurp‐P53 achieved noticeable therapeutic effect compared with Ad‐P53; 24 days after treatment, Ad‐P53 also achieved noticeable therapeutic effect; and till the end of the experiment (31 days later), AdSup‐53 achieved a significantly greater therapeutic effect than Ad‐53 (p < 0.01; Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Anti‐tumor effect and apoptosis‐inducing role of AdSurp‐P53 in nude mice. (A), Compared with the control group, both AdSurp‐P53 and Ad‐P53 achieved noticeable therapeutic effects in mice bearing gallbladder cancer EH‐GB1 xenografts, AdSurp‐P53 showed better anti‐tumor efficacy than Ad‐P53, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. (B), H&E staining, immunostaining, and TUNEL labeling showed cancer cell pathomorphological changes, P53 expression and apoptosis. (C), Apoptotic cell percentages were counted in 5 high‐power fields, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 compared with control group.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed that the cancer cells in Ad‐P53 group grew well, only with small patches of necrosis, and cells in AdSurp‐P53 group had large patches of necrosis (Figure 5B; upper row). There were more P53 positive cancer cells in AdSurp‐P53 group than in Ad‐P53 group (Figure 5B; middle row). TUNEL labeling showed AdSurp‐P53 induced more severe apoptosis in cancer cells than Ad‐P53 (Figure 5B; low row). Apoptotic cells were observed under 5 high power fields (Figure 5C). The ratio of TUNEL positive cells in control group (7.2 ± 2.6%) was significantly lower than those in AdSurp‐P53 group (33.4 ± 8.4%; p = 0.0002), and Ad‐P53 group (21.6 ± 8.6%; p = 0.0073).

4. Discussion

Gene therapy has witnessed ups and downs ever since its emergence. It was not until the end of 2009, good news finally comes after a long‐time waiting (Maguire et al., 2009; Cideciyan et al., 2009; Cartier et al., 2009; Christine et al., 2009; Lees et al., 2009). These improvements have cast new lights for gene therapy. However, scientists want more from gene therapy; what they want with gene therapy is to treat cancer, the greatest threat of human health, not just a few gene‐deficiency related diseases. Compared with the single gene‐deficiency disorders, development of cancer is very complicated and involves multiple genes. Therefore, screening of effective genes is one of the greatest challenges in cancer gene therapy, followed by the safety of the vector system.

Researches on cancer genetics have provided more target genes which can be used for gene therapy of tumors. Regarding the genetic defect of tumor cells, scientists have designed many adenoviruses of anti‐tumor genes, including the anti‐angiogenesis gene such as Canstatin (He et al., 2009) and Endostatin (Zhang et al., 2004), immunoregulatory gene such as γ‐Interferon gene (Su et al., 2006), tumor suppressor genes such as P16 (Castillo and Kowalik, 2002; Ma et al., 2009) and P53 (Wang et al., 2008; Su et al., 2008), etc; all of them have achieved certain therapeutic effect. A great deal of researches have been done on P53 over the passed two decades; P53 as a tumor suppressor gene is closely associated with the development, progression and prognosis of cancer patients. The C‐terminal of P53 protein can detect DNA damage and can strongly bind with the damage to participate in DNA repair, either by interaction with other repair genes or by direct repair. Besides, P53 protein can bind to DNA transcription regulation point and induce expression of growth inhibitory gene such as p21WAF1/CIP1/MDA6, inhibiting cyclin D1‐mediated G1/S transformation, which is beneficial for DNA damage repair by initiating programmed cell death (Castillo and Kowalik, 2002; Hew et al., 2011; Khalil et al., 2011). More than half of human cancers are related to P53 abnormality. Therefore, p53 is taken as a tumor suppresser gene with confirmed therapeutic effect, and becomes the candidate anti‐tumor gene in the current study.

In September 2011, a research group reported an oncolytic poxvirus engineered for replication, transgene expression and amplification in cancer cells harboring activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)/Ras pathway in a clinical trial. JX‐594 was demonstrated to selectively infect, replicate and express transgene products in cancer tissue after intravenous infusion, in a dose‐related fashion. Normal tissues were not affected clinically. This success gives us a great encouragement and tells us that the oncolytic viral vector is a very good potential direction for treatment of metastatic or solid tumors (Breitbach et al., 2011). Since many tumors have their own specific tumor markers or antigens, whose expression is regulated by tumor‐specific cis‐acting elements or trans‐acting factors. A very important way to achieve the tumor‐specific virus replication is to place the viral proliferation genes under the control of tumor‐specific cis‐acting elements. However, most existing tumor‐specific promoter‐mediated oncolytic adenoviruses are limited by the less tumor types, low efficacy, and poor safety. Apoptosis inhibitor Survivin, belongs to IAP family, participates in embryonic cell development and cell cycle regulation, and inhibit cell apoptosis via multiple ways (Shariat et al., 2007; Krambeck et al., 2007). Survivin is present in embryonic tissues and most tumor tissues, but not in normal adults (except for the thymus). Expression of Survivin in malignant tumors is highly selective; it is highly expressed in the most commonly seen human tumors including lung cancer, colon cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer, non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma, and extra‐hepatic cholangio‐carcinomas including gallbladder cancer, and is associated with tumor recurrence and metastasis, making it a common marker for tumor diagnosis (Duffy et al., 2007). Our experiment also showed that Survivin expresses positively in gallbladder and hepatocellular cancer cell lines, and not in normal cell lines. Therefore, the Survivin promoter‐mediated oncolytic adenovirus has a potential to achieve a wide spectrum anti‐tumor effect against most human cancers.

By combining the gene therapy and viral therapy for tumors, the Survivin promoter‐regulated CRAd carrying P53 was constructed, its specific proliferation and anti‐tumor effect against gallbladder cancer were studied. We concluded that the Survivin promoter‐regulated CRAd possesses a high proliferative activity and can effectively express the anti‐tumor gene in Survivin‐positive cancer cells, therefore achieving an enhanced cytotoxic effect against tumor cells and a slight influence on normal cells. The in vivo study in nude mice bearing gallbladder cancer also found that the Survivin promoter‐regulated CRAd can induce apoptosis in more cancer cells, and it has a stronger tumor inhibitory effect than non‐proliferative adenovirus Ad‐P53. The Survivin promoter‐regulated CRAd was improved with the efficiency of viral transfection and gene expression compared with the traditional Ad‐P53 strategy. Theoretically, the Survivin promoter‐mediated oncolytic adenovirus is a wide spectrum anti‐tumor viral product, and is expected to treat cancer patients who do not respond to chemoradiotherapy or who have lost the chance for surgical treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (81071866, 30872507, 81172019).

Liu Chen, Sun Bin, An Ni, Tan Weifeng, Cao Lu, Luo Xiangji, Yu Yong, Feng Feiling, Li Bin, Wu Mengchao, Su Changqing and Jiang Xiaoqing, (2011), Inhibitory effect of Survivin promoter‐regulated oncolytic adenovirus carrying P53 gene against gallbladder cancer, Molecular Oncology, 5, doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.10.001.

Contributor Information

Changqing Su, Email: suchangqing@gmail.com.

Xiaoqing Jiang, Email: jxq1225@sina.com.

References

- Bagheri, N. , Shiina, M. , Lauffenburger, D.A. , Korn, W.M. , 2011. A dynamical systems model for combinatorial cancer therapy enhances oncolytic adenovirus efficacy by mek-inhibition. PLoS Comput. Biol.. 7, e1001085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbach, C.J. , Burke, J. , Jonker, D. , Stephenson, J. , Haas, A.R. , Chow, L.Q. , Nieva, J. , Hwang, T.H. , Moon, A. , Patt, R. , Pelusio, A. , Le Boeuf, F. , Burns, J. , Evgin, L. , De Silva, N. , Cvancic, S. , Robertson, T. , Je, J.E. , Lee, Y.S. , Parato, K. , Diallo, J.S. , Fenster, A. , Daneshmand, M. , Bell, J.C. , Kirn, D.H. , 2011. Intravenous delivery of a multi-mechanistic cancer-targeted oncolytic poxvirus in humans. Nature. 477, 99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budanov, A.V. , Karin, M. , 2008. p53 target genes sestrin1 and sestrin2 connect genotoxic stress and mTOR signaling. Cell. 134, 451–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier, N. , Hacein-Bey-Abina, S. , Bartholomae, C.C. , Veres, G. , Schmidt, M. , Kutschera, I. , Vidaud, M. , Abel, U. , Dal-Cortivo, L. , Caccavelli, L. , Mahlaoui, N. , Kiermer, V. , Mittelstaedt, D. , Bellesme, C. , Lahlou, N. , Lefrère, F. , Blanche, S. , Audit, M. , Payen, E. , Leboulch, P. , l'Homme, B. , Bougnères, P. , Von Kalle, C. , Fischer, A. , Cavazzana-Calvo, M. , Aubourg, P. , 2009. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science. 326, 818–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, J.P. , Kowalik, T.F. , 2002. Human cytomegalovirus immediate early proteins and cell growth control. Gene. 290, 19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. , Chen, D. , Manome, Y. , Dong, Y. , Fine, H.A. , Kufe, D.W. , 1995. Breast cancer selective gene expression and therapy mediated by recombinant adenoviruses containing the DF3/MUC1 promoter. J. Clin. Invest.. 96, 2775–2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christine, C.W. , Starr, P.A. , Larson, P.S. , Eberling, J.L. , Jagust, W.J. , Hawkins, R.A. , VanBrocklin, H.F. , Wright, J.F. , Bankiewicz, K.S. , Aminoff, M.J. , 2009. Safety and tolerability of putaminal AADC gene therapy for Parkinson disease. Neurology. 73, 1662–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan, A.V. , Hauswirth, W.W. , Aleman, T.S. , Kaushal, S. , Schwartz, S.B. , Boye, S.L. , Windsor, E.A. , Conlon, T.J. , Sumaroka, A. , Roman, A.J. , Byrne, B.J. , Jacobson, S.G. , 2009. Vision 1 year after gene therapy for Leber's congenital amaurosis. N. Engl. J. Med.. 361, 725–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, M.J. , O'donovan, N. , Brennan, D.J. , Gallagher, W.M. , Ryan, B.M. , 2007. Survivin: a promising tumor biomarker. Cancer Lett.. 249, 49–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldser, D.M. , Kostova, K.K. , Winslow, M.M. , Taylor, S.E. , Cashman, C. , Whittaker, C.A. , Sanchez-Rivera, F.J. , Resnick, R. , Bronson, R. , Hemann, M.T. , Jacks, T. , 2010. Stage-specific sensitivity to p53 restoration during lung cancer progression. Nature. 468, 572–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Saez, I. , Lacroix, F.B. , Blot, D. , Gabel, F. , Skoufias, D.A. , 2011. Structural characterization of HBXIP: the protein that interacts with the anti-apoptotic protein survivin and the oncogenic viral protein HBx.J. Mol. Biol.. 405, 331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallenbeck, P.L. , Chang, Y.N. , Hay, C. , Golightly, D. , Stewart, D. , Lin, J. , Phipps, S. , Chiang, Y.L. , 1999. A novel tumor-specific replication-restricted adenoviral vector for gene therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum. Gene Ther.. 10, 1721–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X.P. , Su, C.Q. , Wang, X.H. , Pan, X. , Tu, Z.X. , Gong, Y.F. , Gao, J. , Liao, Z. , Jin, J. , Wu, H.Y. , Man, X.H. , Li, Z.S. , 2009. E1B-55kD-deleted oncolytic adenovirus armed with canstatin gene yields an enhanced anti-tumor efficacy on pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett.. 285, 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemminki, O. , Bauerschmitz, G. , Hemmi, S. , Lavilla-Alonso, S. , Diaconu, I. , Guse, K. , Koski, A. , Desmond, R.A. , Lappalainen, M. , Kanerva, A. , Cerullo, V. , Pesonen, S. , Hemminki, A. , 2011. Oncolytic adenovirus based on serotype 3. Cancer Gene Ther.. 18, 288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hew, H.C. , Liu, H. , Miki, Y. , Yoshida, K. , 2011. PKCδ regulates Mdm2 independently of p53 in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. Mol. Carcinog.. 10.1002/mc.20748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.I. , Chang, J.F. , Kirn, D.H. , Liu, T.C. , 2009. Targeted genetic and viral therapy for advanced head and neck cancers. Drug Discov. Today. 14, 570–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gene therapy clinical trials worldwide. J. Gene Med.. http://www.wiley.com//legacy/wileychi/genmed/clinical updated June 2011, (accessed 22.09.11) [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L. , Shen, A. , Boyle, L. , Kunich, J. , Pandey, K. , Lemmon, M. , Hermiston, T. , Giedlin, M. , McCormick, F. , Fattaey, A. , 2002. Selectively replicating adenoviruses targeting deregulated E2F activity are potent, systemic antitumor agents. Cancer Cell. 1, 325–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, A. , Morgan, R.N. , Adams, B.R. , Golding, S.E. , Dever, S.M. , Rosenberg, E. , Povirk, L.F. , Valerie, K. , 2011. ATM-dependent ERK signaling via AKT in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell Cycle. 10, 481–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krambeck, A.E. , Dong, H. , Thompson, R.H. , Kuntz, S.M. , Lohse, C.M. , Leibovich, B.C. , Blute, M.L. , Sebo, T.J. , Cheville, J.C. , Parker, A.S. , Kwon, E.D. , 2007. Survivin and b7-h1 are collaborative predictors of survival and represent potential therapeutic targets for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res.. 13, 1749–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara, T. , Brough, D.E. , Kovesdi, I. , Kufe, D.W. , 2000. Selectivity of a replication-competent adenovirus for human breast carcinoma cells expressing the MUC1 antigen. J. Clin. Invest.. 106, 763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane, D.P. , Cheok, C.F. , Lain, S. , 2010. p53-based cancer therapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol.. 2, a001222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees, A.J. , Hardy, J. , Revesz, T. , 2009. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 373, 2055–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W. , Zheng, S. , Li, X.F. , Huang, J.J. , Zheng, X. , Li, Z. , 2004. Intra-tumor injection of H101, a recombinant adenovirus, in combination with chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancers: a pilot phase II clinical trial. World J. Gastroenterol.. 10, 3634–3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, P. , Yang, X. , Huang, Y. , Lu, Z. , Miao, Z. , Liang, Q. , Zhu, Y. , Fan, Q. , 2011. Antitumor activity of a combination of rAd2p53 adenoviral gene therapy and radiotherapy in esophageal carcinoma. Cell Biochem. Biophys.. 59, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. , He, X. , Wang, W. , Huang, Y. , Chen, L. , Cong, W. , Gu, J. , Hu, H. , Shi, J. , Li, L. , Su, C. , 2009. E2F promoter-regulated oncolytic adenovirus with p16 gene induces cell apoptosis and exerts antitumor effect on gastric cancer. Dig. Dis. Sci.. 54, 1425–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, A.M. , High, K.A. , Auricchio, A. , Wright, J.F. , Pierce, E.A. , Testa, F. , Mingozzi, F. , Bennicelli, J.L. , Ying, G.S. , Rossi, S. , Fulton, A. , Marshall, K.A. , Banfi, S. , Chung, D.C. , Morgan, J.I. , Hauck, B. , Zelenaia, O. , Zhu, X. , Raffini, L. , Coppieters, F. , De Baere, E. , Shindler, K.S. , Volpe, N.J. , Surace, E.M. , Acerra, C. , Lyubarsky, A. , Redmond, T.M. , Stone, E. , Sun, J. , McDonnell, J.W. , Leroy, B.P. , Simonelli, F. , Bennett, J. , 2009. Age-dependent effects of RPE65 gene therapy for Leber's congenital amaurosis: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 374, 1597–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins, C.P. , Brown-Swigart, L. , Evan, G.I. , 2006. Modeling the therapeutic efficacy of p53 restoration in tumors. Cell. 127, 1323–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi, M. , Kanai, F. , Tateishi, K. , Taniguchi, H. , Marignani, P.A. , Yoshida, Y. , Shiratori, Y. , Hamada, H. , Omata, M. , 2001. Target gene therapy for alpha-fetoprotein-producing hepatocellular carcinoma by E1B55k-attenuated adenovirus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.. 282, 529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opyrchal, M. , Aderca, I. , Galanis, E. , 2009. Phase I clinical trial of locoregional administration of the oncolytic adenovirus ONYX-015 in combination with mitomycin-C, doxorubicin, and cisplatin chemotherapy in patients with advanced sarcomas. Methods Mol. Biol.. 542, 705–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaki, T. , Tanio, Y. , Tachibana, I. , Hosoe, S. , Kumagai, T. , Kawase, I. , Oikawa, S. , Kishimoto, T. , 1994. Gene therapy for carcinoembryonic antigen-producing human lung cancer cells by cell type-specific expression of herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene. Cancer Res.. 54, 5258–5261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr, M.J. , Manome, Y. , Tanaka, T. , Wen, P. , Kufe, D.W. , Kaelin, W.G. , Fine, H.A. , 1997. Tumor-selective transgene expression in vivo mediated by an E2F-responsive adenoviral vector. Nat. Med.. 3, 1145–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z. , 2005. Current status of gendicine in China: recombinant human Ad-p53 agent for treatment of cancers. Hum. Gene Ther.. 16, 1016–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.Y. , Won, J.H. , Rutherford, T. , Fujii, T. , Zelterman, D. , Pizzorno, G. , Sapi, E. , Leavitt, J. , Kacinski, B. , Crystal, R. , Schwartz, P. , Deisseroth, A. , 2001. The use of the L-plastin promoter for adenoviral-mediated, tumor-specific gene expression in ovarian and bladder cancer cell lines. Cancer Res.. 61, 4405–4413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rödel, F. , Reichert, S. , Sprenger, T. , Gaipl, U.S. , Mirsch, J. , Liersch, T. , Fulda, S. , Rödel, C. , 2011. The role of survivin for radiation oncology: moving beyond apoptosis inhibition. Curr. Med. Chem.. 18, 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Y.K. , Wu, A.T. , Geethangili, M. , Huang, M.T. , Chao, W.J. , Wu, C.H. , Deng, W.P. , Yeh, C.T. , Tzeng, Y.M. , 2011. Identification of antrocin from Antrodia camphorata as a selective and novel class of small molecule inhibitor of Akt/mTOR signaling in metastatic breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol.. 24, 238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, R. , Schuur, E.R. , Lim, H.Y. , Henderson, G.A. , Simons, J.W. , Henderson, D.R. , 1997. Prostate attenuated replication competent adenovirus (ARCA) CN706: a selective cytotoxic for prostate-specific antigen-positive prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res.. 57, 2559–2563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubanyi, G.M. , 2001. The future of human gene therapy. Mol. Aspects Med.. 22, 113–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, B.M. , O'Donovan, N. , Duffy, M.J. , 2009. Survivin: a new target for anti-cancer therapy. Cancer Treat. Rev.. 35, 553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariat, S.F. , Ashfaq, R. , Karakiewicz, P.I. , Saeedi, O. , Sagalowsky, A.I. , Lotan, Y. , 2007. Survivin expression is associated with bladder cancer presence, stage, progression, and mortality. Cancer. 109, 1106–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, X. , Zhou, Y. , Jia, R. , Xu, X. , Wang, H. , Hu, J. , Ge, S. , Fan, X. , 2010. Inhibition of retinoblastoma in vitro and in vivo with conditionally replicating oncolytic adenovirus H101. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.. 51, 2626–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, C. , Peng, L. , Sham, J. , Wang, X. , Zhang, Q. , Chua, D. , Liu, C. , Cui, Z. , Xue, H. , Wu, H. , Yang, Q. , Zhang, B. , Liu, X. , Wu, M. , Qian, Q. , 2006. Immune gene-viral therapy with triplex efficacy mediated by oncolytic adenovirus carrying interferon-gamma gene yields efficient antitumor activity in immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice. Mol. Ther.. 13, 918–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, C. , Cao, H. , Tan, S. , Huang, Y. , Jia, X. , Jiang, L. , Wang, K. , Chen, Y. , Long, J. , Liu, X. , Wu, M. , Wu, X. , Qian, Q. , 2008. Toxicology profiles of a novel p53-armed replication-competent oncolytic adenovirus in rodents, felids, and nonhuman primates. Toxicol. Sci.. 106, 242–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukuda, K. , Wiewrodt, R. , Molnar-Kimber, K. , Jovanovic, V.P. , Amin, K.M. , 2002. An E2F-responsive replication-selective adenovirus targeted to the defective cell cycle in cancer cells: potent antitumoral efficacy but no toxicity to normal cell. Cancer Res.. 62, 3438–3447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, A. , Kirsch, D.G. , McLaughlin, M.E. , Tuveson, D.A. , Grimm, J. , Lintault, L. , Newman, J. , Reczek, E.E. , Weissleder, R. , Jacks, T. , 2007. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 445, 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Su, C. , Cao, H. , Li, K. , Chen, J. , Jiang, L. , Zhang, Q. , Wu, X. , Jia, X. , Liu, Y. , Wang, W. , Liu, X. , Wu, M. , Qian, Q. , 2008. A novel triple-regulated oncolytic adenovirus carrying p53 gene exerts potent antitumor efficacy on common human solid cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther.. 7, 1598–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.X. , Wang, D. , Wang, G. , Zhang, Q.H. , Liu, J.M. , Peng, P. , Liu, X.H. , 2010. Clinical study of recombinant adenovirus-p53 combined with fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol.. 136, 625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q. , Nie, M. , Sham, J. , Su, C. , Xue, H. , Chua, D. , Wang, W. , Cui, Z. , Liu, Y. , Liu, C. , Jiang, M. , Fang, G. , Liu, X. , Wu, M. , Qian, Q. , 2004. Effective gene-viral therapy for telomerase-positive cancers by selective replicative-competent adenovirus combining with endostatin gene. Cancer Res.. 64, 5390–5397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q. , Chen, G. , Peng, L. , Wang, X. , Yang, Y. , Liu, C. , Shi, W. , Su, C. , Wu, H. , Liu, X. , Wu, M. , Qian, Q. , 2006. Increased safety with preserved antitumoral efficacy on hepatocellular carcinoma with dual-regulated oncolytic adenovirus. Clin. Cancer Res.. 12, 6523–6531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]