Abstract

The Aurora‐A gene encodes a serine/threonine protein kinase that is frequently overexpressed in several types of human tumors. The overexpression of Aurora‐A has been observed to associate with the grades of differentiation, invasive capability and distant lymph node metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). However, the molecular mechanism by which Aurora‐A promotes malignant development of ESCC is still largely unknown. In this study, we show that Aurora‐A overexpression enhances tumor cell invasion and metastatic potential in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, Aurora‐A overexpression inhibits the degradation of β‐catenin, promotes its dissociation from cell–cell contacts and increases its nuclear translocation. We also demonstrate for the first time that Aurora‐A directly interacts with β‐catenin and phosphorylates β‐catenin at Ser552 and Ser675. Substitutions of serine residue with alanine at single or both positions substantially attenuate Aurora‐A‐mediated stabilization of β‐catenin, abolish its cytosolic and nuclear localization as well as transcriptional activity. In addition, Aurora‐A overexpression is significantly correlated with increased cytoplasmic β‐catenin expression in ESCC tissues. In view of our results, we propose that Aurora‐A‐mediated phosphorylation of β‐catenin is a novel mechanism of malignancy development of tumor.

Keywords: Aurora-A, β-catenin, Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC)

Highlights

Aurora‐A overexpression enhances tumor cell invasive and metastatic potential.

Aurora‐A inhibits degradation and increases transcriptional activity of β‐catenin.

Aurora‐A phosphorylates β‐catenin at Ser552 and Ser675.

Aurora‐A expression is correlated with cytoplasmic β‐catenin expression.

1. Introduction

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is one of the most common malignant tumors. Despite remarkable advances in diagnostic and therapeutic techniques, the invasive and metastatic stage of ESCC progression still represents the most formidable barrier to successful treatment. The development of ESCC is a multistep, progressive process, and the acquisition of genetic alterations in tumor cells is a hallmark of cancer progression (Lin et al., 2009; Qi et al., 2012). Thus, better understanding of the molecular alterations during ESCC occurrence and progression should greatly improve tumor control and prevention, and may also lead to better clinical treatment.

Aurora‐A, a centrosome‐ and microtubule‐associated protein, is a serine/threonine protein kinase (Katayama and Sen, 2010). The increased attention has now been focused on Aurora‐A kinase because of its interesting role in tumorigenesis. It has been shown that amplification and overexpression of the Aurora‐A occur in several types of human tumors (Bischoff et al., 1998; Jeng et al., 2004; Sen et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 1998). Ectopic expression of Aurora‐A in murine fibroblasts as well as mammary epithelia induces centrosome amplification, aneuploidy, and oncogenic phenotype (Bischoff et al., 1998; Jeng et al., 2004). Further, Aurora‐A overexpression is more frequently associated with higher grade, higher stage, and identified as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in a variety of human cancers (Hamada et al., 2003; Jeng et al., 2004; Neben et al., 2004; Sen et al., 2002). Recently, we have reported that expression of Aurora‐A protein is highly increased in ESCC. Moreover, overexpression of Aurora‐A is shown to associate with the grades of tumor differentiation and invasive capability (Tong et al., 2004). Tanaka et al. (Tanaka et al., 2005) further demonstrate that upregulation of Aurora‐A expression is correlated with distant lymph node metastasis of ESCC. These clinical studies suggest that Aurora‐A overexpression is closely associated with the development of ESCC. However, direct evidence for a role of Aurora‐A in tumor development and metastasis is lacking and the molecular mechanism for the promotion of ESCC development by Aurora‐A is currently poorly understood.

β‐catenin is an ubiquitously distributed protein with multiple functions, which plays a critical role in tumorigenesis and development through its effects on E‐cadherin‐mediated intercellular adhesion and Wnt/wingless pathway (Nelson and Nusse, 2004). In response to Wnt signals, GSK‐3β (glycogen synthase kinase 3β) is inhibited and phosphorylation of β‐catenin at Ser‐33/Ser‐37 sites is decreased, leading to its stabilization, accumulation. β‐catenin then translocates to the nucleus as an activator of T‐cell factor (TCF)/lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF) transcription factors to stimulate transcription of a variety of growth‐related genes (Bienz, 2005; Bienz and Clevers, 2000; Saito‐Diaz et al., 2013). Increased β‐catenin‐TCF/LEF‐1 transactivation by enhanced β‐catenin stability is found in a wide variety of human cancers (Morin, 1999; Zhou et al., 2005). However, no data are available to indicate whether Aurora‐A regulates β‐catenin in ESCC.

In the present study, we illustrated that Aurora‐A overexpression promoted tumor cell invasion and metastatic potential in vitro and in vivo. We also elucidated that Aurora‐A inhibited the degradation of β‐catenin and promoted its dissociation from cell–cell contacts, nuclear translocation, and transcriptional activity upregulation by direct phosphorylating β‐catenin at Ser552 and Ser675. Overall, these studies reveal critical role of Aurora‐A which contributes to the malignancy development of ESCC.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Reagents and plasmids

The antibodies were from the following sources: anti‐Aurora‐A, anti‐β‐catenin, anti‐GSK‐3β, anti‐Gadd45, anti‐P‐β‐catenin, anti‐PS33‐β‐catenin and anti‐PS37‐catenin antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology; other antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. pEGFP‐Aurora‐A and pEGFP‐β‐catenin were constructed by inserting their open reading frames into pEGFP‐C1 vectors, respectively. Aurora‐A shRNA vector was generated by inserting target sequence of Aurora‐A into pGCsi‐U6/neo/GFP vector. Myc‐tagged β‐catenin was made by inserting the open reading frame of β‐catenin into pCS2‐MT vector. GST‐Gadd45, GST‐GSK‐3β, GST‐Aurora‐A, GST‐β‐catenin and GST‐β‐actin were constructed by inserting their open reading frames into pGEX‐5X‐1 plasmids, respectively. The β‐catenin mutants were generated by site‐directed mutagenesis and confirmed by sequencing.

2.2. Cell culture and transfection

The KYSE150 cell line was generously provided by Dr Shimada of Kyoto University (Shimada et al., 1992). KYSE180, Colo680 and EC9706 cell lines were stored in our laboratory. The ESCC cells were maintained in RPMI‐1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Transient transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the cells were analyzed 2 days after the transfection. In the stable transfection, Aurora‐A overexpression clones in KYSE150 cells or knockdown clones in EC9706 cells were selected by G‐418 sulfate (Invitrogen) for 10–14 days.

2.3. In vitro migration and invasion assays

Invasion and migration assays were carried out by using Transwell motility chambers and performed as previously described (Tong et al., 2004).

2.4. Xenograft assays

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with relevant institutional and national guidelines and regulations. The cells were injected subcutaneously in the axillary region of four‐week‐old immune‐deficient mice (BALBC/C‐nu/nu, Vital River Co.). Tumor volumes were calculated using the formula (length) × (width)2/2. The mice were euthanized at the end of 12 weeks after injection and examined for subcutaneous tumor growth and metastasis development. Specimens for histological examination were fixed in 10% formaldehyde for 24 h, embedded in paraffin. 4‐μm sections were then cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and observed under a microscope.

2.5. Protein preparation and Western blot analysis

For whole cell protein extraction, cells were lysed with ice‐cold lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, as described previously (Tong et al., 2004). The nuclear, cytoplasmic and membrane protein were prepared and Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (Ji et al., 2007).

2.6. Protein stability experiments

The cells were transfected with or without GFP‐tagged wild‐type (WT) or mutants of β‐catenin plasmids for 48 h, 100 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) (Sigma) was added to the cell culture and then cells were harvested at the indicated time points. To determine the effects of proteasome inhibitors on β‐catenin protein stability, the cells were pre‐incubated with 20 μM MG132 (benzyloxy‐carbonyl‐Leu‐Leu‐Leu‐aldehyde) before the addition of CHX.

2.7. Semiquantitative reverse transcription (RT)‐PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. RT‐PCR was performed as previously described (Zhou et al., 2005). The primers for the PCR were as follows: β‐catenin: 5′‐ATGGAGTTGGACATGGCCAT‐3′ (forward) and 5′‐CGAGCTGTCTCTACAT CATT‐3′ (reverse), Cyclin D1: 5′‐CCGTCCATGCGGAAGATC‐3′ (forward) and 5′‐ATGGCCAGCGGGAAGAC‐3′ (reverse), MMP7: 5′‐AGATGTGGAGTGCCAG ATGT‐3′ (forward) and 5′‐TAGACTGCTACCATCCGTCC‐3′(reverse), GAPDH: 5′‐GCTGAGAACGGGAAGCTTGT‐3′ (forward) and 5′‐GCCAGGGGTGCTAA GCAGTT‐3′ (reverse). GAPDH was used as an internal standard.

2.8. Immunoprecipitation and GST pull‐down assays

Immunoprecipitation and GST pull‐down assays were performed as previously described (Ji et al., 2007).

2.9. Immunofluorescence analysis

Cells were grown on glass chamber slides and transfected with or without GFP‐tagged WT or mutants of β‐catenin plasmids for 48 h, fixed with methanol, and incubated with monoclonal anti‐β‐catenin antibody overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with TRITC‐conjugated goat anti‐mouse IgG for 1 h. The nuclei were labeled with 0.1 μg/ml DAPI (4',6'‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole) for 15 min. The images were taken under a confocal fluorescent microscope.

2.10. Expression profiling array analysis

Expression profiling array analysis was performed by Capitalbio Corp (Beijing, China).

2.11. Quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR

Real‐time quantitative RT‐PCR analysis was performed using the ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The specific gene expression was detected by using SYBR Premix EX TaqII (TaKaRa). Primer sequences for CD44, IL6, NFKBIA, CCND1, TYMS, LCN2, ALDH1A3, MMP2, SERPINA1, BAMBI and TCF7 will be provided upon request.

2.12. In vitro Aurora‐A kinase assay

Purified Aurora‐A protein was incubated for 30 min with purified GST fusion proteins of WT β‐catenin or various β‐catenin mutants and [γ‐32P]ATP in reaction buffer (8 mM MOPS/NaOH pH 7.0, 0.2 mM EDTA). Reaction mixtures were resolved by SDS–PAGE and phosphorylated proteins were detected by autoradiography.

2.13. TCF/LEF‐luciferase reporter assay

Cells grown on 24‐well plates were transfected with WT or mutants of β‐catenin for TCF‐luciferase reporter (TOPflash) or its mutated control reporter (FOPflash). 48 h after transfection, the cells were lysed and the luciferase activity was measured and normalized to the corresponding Renilla activity using the dual luciferase assay kit (Promega). The normalized FOPflash values were subtracted from the corresponding TOPflash values.

2.14. Tissue specimens and immunohistochemistry

Fresh tissue specimens from pathologically confirmed ESCCs and adjacent histologically normal tissues were taken from patients presented at the Cancer Institute & Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China) after surgery and immediately stored at −80 °C until use. None of the patients had received radio‐ or chemotherapy before surgery. The samples were obtained following written informed consent from patients and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cancer Institute & Hospital of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. Immunohistochemical analysis was done as described previously (Tong et al., 2004).

2.15. Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were done using SPSS13.0 software and all data were expressed as the mean ± SD. The differences in results between groups were compared using Student's t test. Association between Aurora‐A and β‐catenin was examined using the Chi‐square test. Statistical significance was defined at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Aurora‐A overexpression promotes tumor cell invasion and metastasis in vitro and in vivo

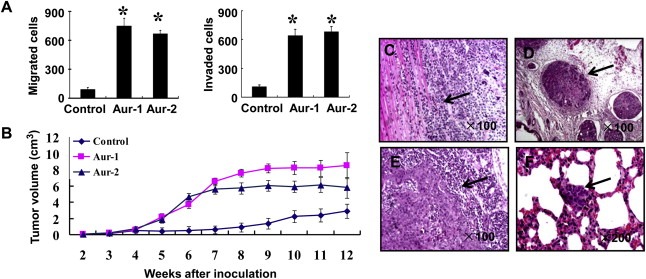

To investigate the effect of Aurora‐A on the invasion potential of esophageal cancer cells, clones of stable Aurora‐A overexpression (Aur‐1and Aur‐2) or the empty vector (control) derived from KYSE150 cells were used and analyzed by in vitro migration and invasion assay. As shown in Figure 1A, Aur cells significantly increased cell migration and invasion potential (P < 0.01) compared with control cells. To further elucidate whether tumor cells with Aurora‐A‐overexpressing can potentiate tumor development and metastasis in vivo, the nude mice xenograft model was used. Our data showed that the tumors from Aur cells in nude mice grew more quickly than that from control cells (Figure 1B). Further, the more invasive tumors from Aur cells frequently invaded muscles (Figure 1C) compared with control tumors. Small tumor masses were found surrounding the associated blood vessels in the tumor tissue from mice injected with Aur cells (Figure 1D). Local lymph node metastasis was detected from mice injected with Aur cells, and approximately 70% of the lymph node was replaced by malignant cells (Figure 1E). Moreover, H&E staining demonstrated the presence of microscopic metastasis in the lungs of mice receiving injections of Aur cells (Figure 1F), whereas no lymph node and lung metastasis was found in the group of mice injected with control cells (Table 1). To further investigate the function of Aurora‐A gene, clone of Aurora‐A stable knockdown was established in EC9706 cells. Western blot showed that Aurora‐A expression markedly decreased in Aurora‐A knockdown (Aurora‐A siRNA) cells compared with control (Control siRNA) cells (Supplementary Figure S1A). Furthermore, the ability of migration and invasion in vitro was inhibited dramatically by Aurora‐A knockdown (Supplementary Figure S1B). We then examined the effects of Aurora‐A knockdown on malignant phenotypes of tumor cells in vivo. As shown in Supplementary Figure S1C, tumor cell growth was suppressed by Aurora‐A knockdown. Moreover, Aurora‐A knockdown inhibited the ability of cells to invade surrounding muscle tissues (Supplementary Figure S1D), and resulted in a significant decrease of lymph node (Supplementary Figure S1E) and lung metastases (Supplementary Figure S1F) in vivo (Table S1). These results were consistent with above‐mentioned effects of Aurora‐A overexpression. These observations suggest that Aurora‐A overexpression possesses potentials of promoting ESCC cell invasion and metastasis in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 1.

Overexpression of Aurora‐A promotes ESCC tumor invasion and metastasis. A) The effect of Aurora‐A overexpression on cell migration and invasion ability in vitro. The results were from three separate experiments; bars, SD.*, P < 0.01. B) Aurora‐A overexpression promoted tumor growth in vivo. The xenograft tumor volume was measured at the indicated time points during the period of 12 weeks. C–F) Aurora‐A overexpression promoted tumor cell invasion and metastasis in vivo. Representative images were shown. The mice baring tumor xenografts derived from KYSE150 cells overexpressing Aurora‐A exhibited tumor invasion to the adjacent muscle tissues (C), small tumor masses in blood vessels (D), lymph node metastasis (E), and lung metastasis (F). Arrows indicate the presence of tumor invasion to the adjacent muscle tissues or metastatic tumor in tumor or lung slice.

Table 1.

The metastasis in nude mice comparison between Aurora‐A overexpression and control cell lines.

| Cell line | Nude mice (n) | Lung metastasis (n) | Lymph node metastasis (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aur‐1 | 6 | 3 | 2 |

| Aur‐2 | 6 | 6 | 2 |

| Control | 6 | 0 | 0 |

3.2. Aurora‐A overexpression upregulates β‐catenin by increasing its stability

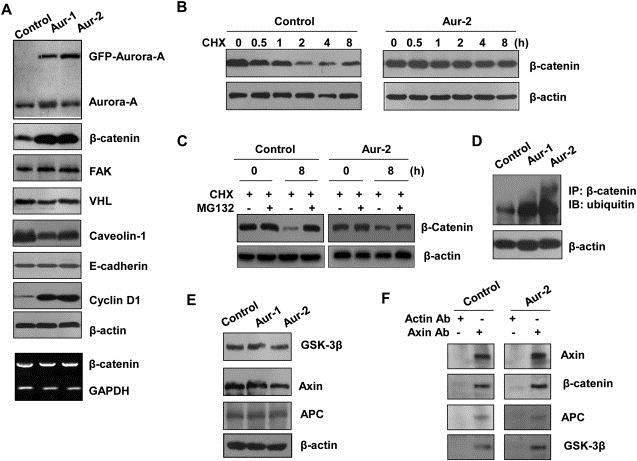

To explore the underlying mechanism by which Aurora‐A promotes tumor malignancy, we examined the expression patterns of different oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes following overexpression of Aurora‐A. It was found that expressions of β‐catenin and Cyclin D1 in Aur cells were higher than that in control cells. Conversely, the level of Caveolin‐1 appeared to decrease, and FAK, VHL and E‐cadherin levels remained unchanged (Figure 2A). The results demonstrate that the altered expression of these genes might contribute to Aurora‐A‐induced malignant development of ESCC.

Figure 2.

Aurora‐A stabilizes β‐catenin protein. A) The upregulated expression of β‐catenin protein in Aurora‐A overexpressing cells. β‐catenin, FAK, VHL, Caveolin‐1, E‐cadherin or Cyclin B1 protein and β‐catenin mRNA (Bottom) levels were examined using immunoblotting and RT‐PCR assay in control, Aur‐1 and Aur‐2 cells. B) The stabilization of β‐catenin in Aurora‐A overexpressing cells. The cells were treated with CHX and collected at the indicated times for immunoblotting analysis. C) The cells were treated with CHX in the presence of MG132, and subjected to immunoblotting analysis. D) The cell protein extracts from control, Aur‐1 and Aur‐2 cells were immunoprecipitated with β‐catenin antibody, followed by immunoblotting assay with ubiquitin antibody. E) The cell lysates were analyzed with antibodies to GSK‐3β, Axin and APC. F) The cellular protein were immunoprecipitated with anti‐Axin antibody, immunocomplexes were analyzed with antibodies against β‐catenin, APC and GSK‐3β.

To explore how Aurora‐A upregulates β‐catenin expression, we examined β‐catenin mRNA level using semiquantitative RT‐PCR and found that mRNA expression of β‐catenin was not altered (Figure 2A Bottom), indicating that posttranscriptional regulation might be responsible for the upregulation of β‐catenin protein level. We next investigated whether upregulation of β‐catenin protein occurs as a result of reduced protein degradation. As shown in Figure 2B, in control cells, 1 h and 2 h treatment of cells with CHX (protein synthesis inhibitor) resulted in 40% and 80% decrease of endogenous β‐catenin but not of β‐actin. However, in Aurora‐A overexpressing cells, the level of β‐catenin was not altered after treatment with CHX, suggesting that Aurora‐A overexpression might maintain β‐catenin stability. To further test whether the stabilization of β‐catenin is due to disruption of ubiquitin mediated proteasomal degradation, we treated cells with CHX in the presence of proteasomal inhibitor MG132. As shown in Figure 2C, the decreased expression of β‐catenin could be rescued by MG132 in both Aurora‐A‐overexpressing and control cells. Furthermore, the level of β‐catenin ubiquitination was greatly increased upon Aurora‐A overexpression, β‐catenin ubiquitination was undetectable in control cells (Figure 2D). Taken together, these results indicate that Aurora‐A overexpression upregulates β‐catenin by inhibiting its proteasomal degradation mediated by ubiquitin pathway.

It is well documented that Axin binds to GSK‐3β, β‐catenin, and adenomatous polyposis coli gene product (APC) to degrade β‐catenin (Ikeda et al., 1998). We examined whether this could explain the effect of Aurora‐A overexpression on upregulating β‐catenin. Nevertheless, the total levels of GSK‐3β, Axin and APC were not significantly affected by Aurora‐A overexpression, as assessed by Western blot (Figure 2E). When Axin was immunoprecipitated with the anti‐Axin antibody, it formed a complex with GSK‐3β, β‐catenin, and APC at the endogenous levels, but Aurora‐A overexpression did not affect the binding of Axin to GSK‐3β, β‐catenin and APC (Figure 2F). The results indicate that Aurora‐A overexpression does not affect the formation of a complex between Axin, GSK‐3β, β‐catenin, and APC. Therefore, Aurora‐A overexpression may upregulate β‐catenin by other means.

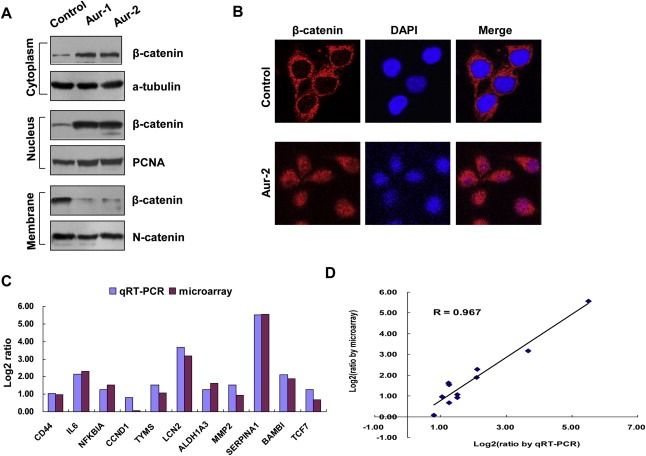

3.3. Overexpression of Aurora‐A alters subcellular localization of β‐catenin

β‐catenin localized in different cellular compartments forms distinct complexes and executes differential cellular function (Bienz, 2005), so we examined whether Aurora‐A overexpression affects β‐catenin subcellular distribution. As shown in Figure 3A, immunoblotting experiments detected an increase in cytosolic and nuclear β‐catenin, whereas the plasma membrane accumulation of β‐catenin was reduced in Aurora‐A overexpression cells compared with control cells. Consistently, immunofluorescence analysis showed that Aurora‐A overexpression resulted in translocation of a portion of β‐catenin from cell–cell contacts into the cytosol and nucleus (Figure 3B). It is known that stabilized β‐catenin translocates to the nucleus, where it interacts with transcription factors of the TCF/LEF‐1 family, leading to the increased expression of genes, such as MMP2 and Cyclin D1. To prove this, the expressions of β‐catenin target genes were measured by expression profiling arrays and quantitative RT‐PCR. The results of expression profiling arrays showed that 11 β‐catenin‐regulated genes were upregulated. Quantitative RT‐PCR analysis gave results consistent with microarray findings (Figure 3C), and both methods showed high correlation (R = 0.967) (Figure 3D). These data indicate that Aurora‐A overexpression promotes β‐catenin dissociation from cell–cell contacts, nuclear translocation, and activates transcription of its targeted genes.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of Aurora‐A alters subcellular localization of β‐catenin. A) The membranous, cytosol and nuclear proteins were isolated from the cells and analyzed with anti‐β‐catenin antibody. α‐tubulin, PCNA and N‐Cadherin were also examined respectively as the controls of different fractions. B) The subcellular distribution of β‐catenin was examined by immunofluorescence in control and Aur‐2 cells. The cells were fixed and stained with an anti‐β‐catenin antibody (red) and DAPI (blue). Pink color indicates overlap of red and blue colors. C) The upregulation of β‐catenin‐regulated genes by Aurora‐A. The levels of mRNA for β‐catenin‐regulated genes were analyzed using microarray and quantitative RT‐PCR in control and Aur‐2 cells. Fold inductions were obtained by normalizing mRNA levels of β‐catenin‐regulated genes in control cell line to that in Aur‐2 cells, and were shown by log2 ratio. D) Comparison of genes expression measurement by microarray and quantitative RT‐PCR. The expression changes in the selected 11‐β‐catenin‐regulated genes exhibited good agreement between the two experimental approaches.

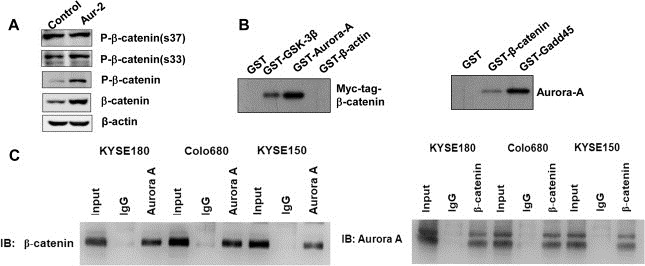

3.4. Aurora‐A interacts with and phosphorylates β‐catenin at ser552 and ser675

It is known that GSK‐3β phosphorylates the cytoplasmic β‐catenin and facilitates its proteasomal degradation (Ikeda et al., 1998). To test whether the increase of β‐catenin protein level is due to decreased GSK‐3β–induced phosphorylation, β‐catenin phosphorylation was assessed by Western blot with antibodies against phospho‐(pS33 or pS37)‐specific β‐catenin. As shown in Figure 4A, Aurora‐A overexpression did not affect the GSK‐3β‐dependent phosphorylation of β‐catenin, but total phosphorylation level of β‐catenin was increased in Aurora‐A overexpression cells. These data indicate that Aurora‐A overexpression increasing β‐catenin stability and transactivation is not mediated by GSK‐3β dependent regulation and other phosphorylation sites could exist on β‐catenin.

Figure 4.

Aurora‐A interacts with β‐catenin. A) The cell lysates were resolved by 10% SDS‐PAGE and immunoblotted with P‐β‐catenin (s37), P‐β‐catenin (s33), P‐β‐catenin and β‐catenin antibody. B–C) The interaction of Aurora‐A with β‐catenin. Myc‐tagged β‐catenin vector was transiently expressed in KYSE150 cells via Lipofectamine transfection. 48 h post‐transfection, whole cell protein extracts were prepared and pulled down with GST and GST‐GSK‐3β, GST‐Aurora‐A and GST‐β‐actin. The immunocomplexes were analyzed by SDS‐PAGE followed by immunoblotting with anti‐Myc antibody (B, Left). GST, GST‐β‐catenin and GST‐Gadd45 were incubated with cell lysates isolated from KYSE150 cells. The GST pull‐down complexes were examined by SDS‐PAGE and immunoblotting with anti‐Aurora‐A antibody (B, Right). The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies to β‐catenin, Aurora‐A, mouse or rabbit IgG. The immunocomplexes were analyzed with anti‐β‐catenin or anti‐Aurora‐A antibody (C).

To address the mechanism by which Aurora‐A regulates β‐catenin, we examined whether Aurora‐A could phosphorylate β‐catenin. We first investigated physical association between Aurora‐A and β‐catenin in vitro. In Figure 4B (Left), KYSE150 cells were transfected with Myc‐tagged β‐catenin vector, and cellular lysates were incubated with a group of GST fusion proteins. Clearly Myc‐tagged β‐catenin was pulled down by GST‐Aurora‐A as well as by GST‐GSK‐3β which was reported previously to interact with β‐catenin. In contrast, GST‐β‐actin and GST alone did not pull‐down Myc‐tagged β‐catenin fusion protein. Next, GST‐β‐catenin protein was incubated with cell lysates from untreated KYSE150 cells and followed by pull‐down assay. As shown in Figure 4B (Right), endogenous Aurora‐A protein was detected in GST‐β‐catenin pull‐down complexes. As a positive control, endogenous Aurora‐A protein was pulled down by GST‐Gadd45. GST alone did not associate with cellular Aurora‐A. In addition, β‐catenin protein was detected in Aurora‐A‐immunoprecipitated complex, and also Aurora‐A protein was detected in β‐catenin‐immunoprecipitated complex in KYSE150 cells (Figure 4C). Similarly, as shown in Figure 4C, Aurora‐A could interact with β‐catenin in KYSE180 and Colo680 cells which had relatively rich levels of endogenous Aurora‐A (Tong et al., 2004).

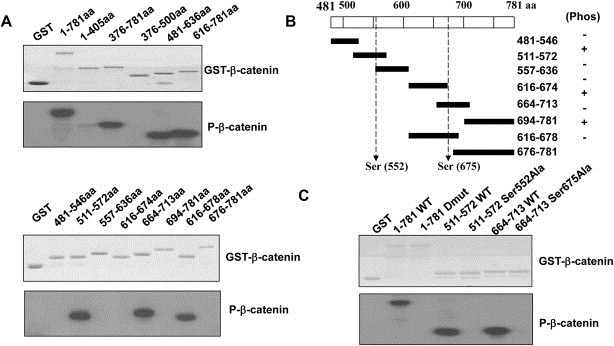

Next, we performed the in vitro kinase assay using purified Aurora‐A protein and recombinant β‐catenin to determine whether Aurora‐A phosphorylates β‐catenin. The results of autoradiography showed that full length GST‐β‐catenin was phosphorylated by Aurora‐A, whereas GST alone was not in this assay (Figure 5A), indicating the specificity of the in vitro reaction. To identify the sites required for phosphorylation of β‐catenin by Aurora‐A, a series of GST‐tagged β‐catenin protein which covered the different regions of β‐catenin were purified as substrates. Figure 5A (Top) showed that the three phosphorylated bands were seen in the GST‐β‐catenin lane correspond to β‐catenin‐(376–781), β‐catenin‐(481–636) and β‐catenin‐(616–781), but β‐catenin fragments including β‐catenin‐(1–405) and β‐catenin‐(376–500) were not phosphorylated by Aurora‐A kinase. To further examine the β‐catenin site involved in phosphorylation, we narrowed down the phosphorylation locations and the β‐catenin protein sequence was divided into a series of peptides with some residues overlap between each contiguous peptide. Figure 5A (Bottom) showed that the three phosphorylated bands were seen in the GST‐β‐catenin lane correspond to β‐catenin‐(511–572), β‐catenin‐(664–713) and β‐catenin‐(616–678), but β‐catenin fragments including β‐catenin‐(481–546), β‐catenin‐(557–636), β‐catenin‐(616–674) and β‐catenin‐(694–781) were not phosphorylated by Aurora‐A kinase. By bioinformatics analysis, Ser552 and Ser675 on β‐catenin were suggested to be candidate phosphorylation sites of Aurora‐A (Figure 5B). To assess if Aurora‐A phosphorylates β‐catenin at Ser552 and Ser567 sites, single (S552A or S567A) and double (S552/567A) phosphorylation site mutants of β‐catenin were used. The kinase assay showed a lack of phosphorylation of the S552A, S675A and S552/567A mutants, implying that Aurora‐A‐induced the phosphorylation of β‐catenin at both the Ser552 and Ser567 residues (Figure 5C). Together, these data convincingly demonstrate that β‐catenin is a novel substrate for Aurora‐A, and can be phosphorylated by Aurora‐A at Ser‐552 and Ser‐675 sites.

Figure 5.

Aurora‐A phosphorylates β‐catenin at ser552 and ser675. The identification of phosphorylating regions of β‐catenin by in vitro Aurora‐A kinase assay. A series of purified GST‐β‐catenin, GST‐β‐catenin S552A, GST‐β‐catenin S675A or GST‐β‐catenin S552/675A proteins were used as substrates for purified Aurora‐A, and subjected to a kinase reaction with [γ‐32P]ATP. Whole kinase reactions were then subjected to electrophoresis followed by autoradiography (A and C). Sequence analysis of β‐catenin for candidate phosphorylation sites of Aurora‐A (B).

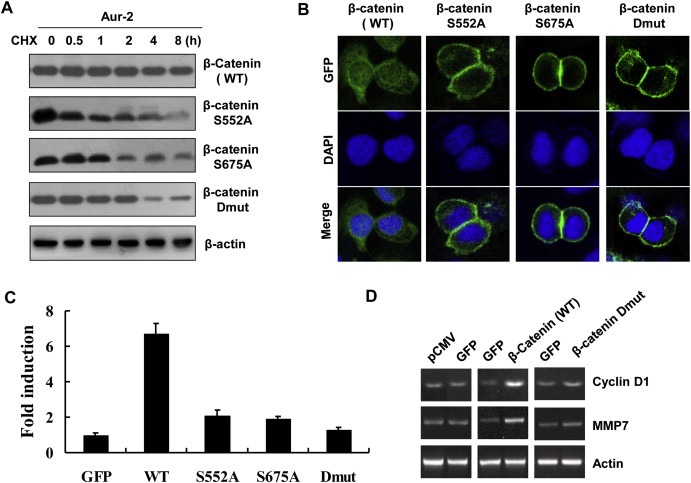

3.5. Phosphorylation of β‐catenin by Aurora‐A increases its stability and transcriptional activity

To understand the functional significance, we first examined that whether β‐catenin phosphorylation at Ser‐552 and Ser‐675 sites by Aurora‐A affects its stability. GFP‐tagged WT and Mutations of β‐catenin at S552A, S675A and S552A/S675A were transfected into Aur‐2 cells treated with CHX. Figure 6A showed that mutants of β‐catenin protein had a short half‐life compare with WT β‐catenin. This result suggests that Aurora‐A inhibit the degradation of β‐catenin probably by its phosphorylation at Ser‐552 and Ser‐675 sites. We further examined whether β‐catenin phosphorylation at Ser‐552 and Ser‐675 sites by Aurora‐A affects its subcellular distribution and TCF/LEF‐1 transcriptional activity. GFP‐tagged WT and Mutations of β‐catenin were transfected into KYSE150 cells. Figure 6B showed that mutants of β‐catenin were primarily localized in cell–cell contacts in contrast to WT β‐catenin that was primarily localized in cytosol and nucleus. Next, the TCF/LEF‐1 luciferase reporter TOP‐FLASH or a control vector FOP‐FLASH was co‐transfected with GFP‐tagged WT β‐catenin or β‐catenin S552A, S675A and S552A/S675A mutants in KYSE150 cells. Expression of WT β‐catenin significantly increased TCF/LEF‐1 transcriptional activity. In contrast to WT β‐catenin, β‐catenin S552A and S675A mutants had reduced transcriptional activity. Double S552A/S675A mutant completely abolished this effect (Figure 6C). Similarly, we confirmed that WT β‐catenin transfection increased expression of β‐catenin target genes including Cyclin D1 and MMP7, whereas the double mutation (S552A/S675A) abolished this effect (Figure 6D). The data indicate that β‐catenin phosphorylation at Ser‐552 and Ser‐675 by Aurora‐A promotes its dissociation from cell–cell contacts, nuclear translocation, and TCF/LEF‐1 transcriptional activity upregulation.

Figure 6.

β‐catenin phosphorylated at ser552 and ser675 by Aurora‐A increases its stability and transcriptional activity. A) GFP‐tagged WT β‐catenin, β‐catenin S552A, β‐catenin S675A or β‐catenin S552/675A vector was transiently expressed in Aur‐2 cells via Lipofectamine transfection. 48 h post‐transfection, the cells were treated with CHX and collected at the indicated times for immunoblotting analysis with anti‐GFP antibody. B) KYSE150 cells expressing GFP‐tagged WT β‐catenin, β‐catenin S552A, β‐catenin S675A or β‐catenin S552/675A were stained with DAPI. C) The luciferase reporter assay. TOP‐FLASH or FOP‐FLASH was co‐transfected with GFP‐tagged WT β‐catenin, β‐catenin S552A, S675A or S552A/S675A mutants in KYSE150 cells. Fold induction was calculated by normalizing luciferase activity of the cells expressing WT β‐catenin or mutant β‐catenin to that in the cells transfected by vector along (GFP). D) Analysis of Cyclin D1 and MMP7 mRNA levels in KYSE150 cells expressing GFP, GFP‐tagged β‐catenin, or β‐catenin S552/675A.

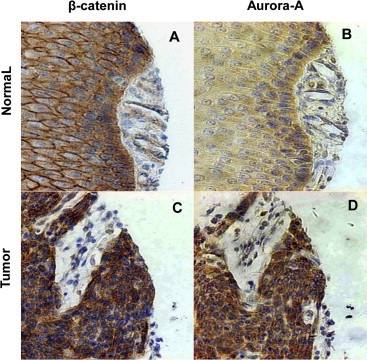

3.6. Expression relevance of Aurora‐A and cytoplasmic β‐catenin in clinical ESCC

To assess whether overexpression of Aurora‐A is really responsible for the subcellular localization of β‐catenin in vivo, we used immunohistochemical assays to examine the expressions and the subcellular localizations of Aurora‐A and β‐catenin in clinical tumor specimens from 129 ESCC patients (Supplementary Table S2). In normal tissues, β‐catenin was located on the membrane (Figure 7A), but enhanced cytoplasmic (94/129, 73%) β‐catenin expression was observed in ESCC (Figure 7C). Meanwhile, normal adjacent tissues presented weak or negative staining of Aurora‐A protein (Figure 7B), however, increased levels of cytoplasmic Aurora‐A expression were widely detected in 94 out of 129 tumor tissues (73%) (Figure 7D), which was consistent with previous report (Tong et al., 2004). More importantly, Table 2 showed that enhanced expression of Aurora‐A was positively correlated with increased cytoplasmic β‐catenin expression (P < 0.0001). These results indicate that overexpression of Aurora‐A leads to accumulation of cytoplasmic β‐catenin in ESCC.

Figure 7.

Aurora‐A overexpression is correlated with cytoplasmic β‐catenin expression in human ESCC tissues. ESCC samples and normal adjacent tissues were collected and subjected to immunohistochemical staining with antibodies to either Aurora‐A or β‐catenin. In normal adjacent esophageal tissues, β‐catenin was located on the membrane (A), Aurora‐A showed no or weak positive staining (B). In esophageal tumor samples, β‐catenin (C) and Aurora‐A (D) exhibited strong cytoplasmic staining.

Table 2.

The expression correlation of Aurora‐A and cytoplasmic β‐catenin in ESCC.

| Cytoplasmic β‐catenin expression | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (−) | (+) | (++) | ||

| Aurora‐A expression | <0.0001 | |||

| (−) | 26 | 3 | 4 | |

| (+) | 6 | 22 | 15 | |

| (++) | 7 | 14 | 22 | |

4. Discussion

In this study, we found that Aurora‐A overexpression significantly promoted growth of ESCC xenografts. A greater invasive capability of Aurora‐A overexpressers was not only revealed by our in vitro assay but also by our in vivo data, which showed a dramatic increase in infiltration of these cells to their adjacent muscle tissues. In addition, the formation of tumor masses surrounding the associated blood vessels in the tumor tissue by Aurora‐A overexpression may favor metastasis of the tumor cells, and in turn contributed to development of ESCC malignancy. More importantly, our results demonstrated clearly that Aurora‐A overexpression in ESCC cells significantly promoted the lung and lymph node metastatic potential. Consistent with these findings, we found that Aurora‐A knockdown inhibited invasion and metastasis of ESCC cells in vitro and in vivo. These results strongly support the notion that increased Aurora‐A expression is critical for facilitating invasion and metastatic of ESCC.

Earlier studies have reported that Aurora‐A participates in multiple cellular functions by means of the phosphorylation of different substrates. Aurora‐A kinase can phosphorylate p53 at Ser315, leading to increased degradation of p53 and facilitating oncogenic transformation of cells (Katayama et al., 2004). The phosphorylation of p53 at Ser‐215 by Aurora‐A abrogates p53 DNA binding and transactivation activity (Liu et al., 2004). Aurora‐A also can activate nuclear factor‐κB (NF‐κB) via inducing IκBα phosphorylation at both the Ser32 and Ser36 residues, leading to carcinogenesis and drug resistance (Briassouli et al., 2007). Therefore, identification of “downstream” targets is crucial for understanding molecular mechanism associated with Aurora‐A in ESCC development. We found that Aurora‐A overexpression was involved in upregulating the expression of β‐catenin. Meanwhile, we found that Aurora‐A regulated β‐catenin at the posttranscriptional level and resulted in increased β‐catenin stability by inhibiting its ubiquitin mediated proteasomal degradation. Furthermore, stabilized β‐catenin translocated to the nucleus from cell–cell contacts, activated transcription of target genes. Therefore, Aurora‐A contributes to the malignant development of ESCC through regulating β‐catenin stability and transcriptional activity.

β‐catenin, functioning as a major component of Wnt signaling, is involved in tumor formation and development (Morin, 1999; Zhou et al., 2005). The canonical mechanism of the regulation of β‐catenin expression includes the Axin/APC/β‐catenin/GSK‐3β complex conformation and its phosphorylation by GSK‐3β at the Ser‐37, and Ser‐33 sites, leading to its degradation. The Wnt stimuli leads to inhibition of GSK‐3β, resulting in a decreased phosphorylation of β‐catenin, accumulation and subsequent translocation to the nucleus (Bienz, 2005; Bienz and Clevers, 2000; Saito‐Diaz et al., 2013). In addition, it has been suggested that Wnt‐dependent downregulation of Axin is one of the mechanisms to stabilize β‐catenin (Yamamoto et al., 1999). However, our results showed that Aurora‐A overexpression did not change expression levels of Axin, GSK‐3β, β‐catenin, and did also not affect their mutual binding. Further, in this study we found that Aurora‐A overexpression increasing total phosphorylation levels of β‐‐catenin was not because of a increase in relative phosphorylation of Ser33 or Ser37 of β‐catenin. These results indicate that Aurora‐A overexpression may regulate β‐catenin through Wnt‐independent signaling.

It has been reported that Wnt‐independent signaling is involved in regulation of β‐catenin activation and tumorigenesis, including G‐protein, hepatocyte growth factor and AKT (Fang et al., 2007; Kawasaki et al., 2000; Papkoff and Aikawa, 1998). In this study, we demonstrated that Aurora‐A interacted with β‐catenin by GST pull‐down and Co‐IP assays in ESCC cells. Our present results indicated that Aurora‐A appeared to phosphorylate β‐catenin at Ser‐552 and Ser‐675 site, and a single substitution of Ser‐552 to Ala, Ser‐675 to Ala or similar substitution of both residues creating a double mutant (S552A/S675A) which mimicked unphosphorylated form, completely abolished Aurora‐A‐mediated β‐catenin phosphorylation. Moreover, the inhibition of degradation and accumulation of the cytosol and nucleus by Aurora‐A were not observed in β‐catenin S552A, S675A or S552A/S675A. Mutation of Ser552 or Ser675 of the Aurora‐A phosphorylation site significantly reduced total transcriptional activity of TCF/LEF‐1. Whereas the double mutation (S552A/S675A) nearly completely abolished transcriptional activity of TCF/LEF‐1 and expression upregulation of β‐catenin target gene (Cyclin D1 and MMP7) induced by Aurora‐A. Taken together, we show for the first time that β‐catenin can be inhibited for its degradation, translocate to the nucleus, where it interacts with transcription factors of the TCF/LEF‐1 family, leading to the increased its transcriptional activity through β‐catenin phosphorylation by Aurora‐A at Ser552 and Ser675 sites, as precedents for multiple distinct kinases targeting the same phosphorylation site of β‐catenin (AKT and AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) for Ser552; PKA (protein kinase A) and PAK1(P21‐activated kinase 1) for Ser675) have been reported (Taurin et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2012). Furthermore, the results herein are the first to show the association between pattern of Aurora‐A expression and pattern of β‐catenin localization in ESCC, further indicating that Aurora‐A may modulate the β‐catenin pathway in esophageal cancer. Our data provide new insight into the role of Aurora‐A in tumor promotion via activity of the β‐catenin pathway.

5. Conclusion

Our studies reveal that the effects of Aurora‐A, promoting invasion and metastasis of ESCC, inhibiting the degradation of β‐catenin and promoting its dissociation from cell–cell contacts, nuclear translocation, and transcriptional activity upregulation are mediated through phosphorylating β‐catenin at Ser552 and Ser675, which represents a novel and important mechanism underlying the effects of Aurora‐A during tumor development. The demonstration of a cross‐talk between Aurora‐A and β‐catenin provides considerable insight into the further understanding tumor cell invasion and metastasis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests to disclose.

Supporting information

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary Figure S1 Knockdown of Aurora‐A inhibits ESCC tumor invasion and metastasis. A) Western blot analysis of Aurora‐A expression in Aurora‐A siRNA and Control siRNA groups. B) The effect of Aurora‐A knockdown on cell migration and invasion ability in vitro. The results were from three separate experiments; bars, SD.*, P < 0.01. C) Aurora‐A Knockdown suppressed tumor growth in vivo. The xenograft tumor volume was measured at the indicated time points during the period of 12 weeks. D–F) Aurora‐A knockdown inhibited tumor cell invasion and metastasis in vivo. Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining sections of tumor invasion to the adjacent muscle tissues (D), lymph node (E) and lung (F) metastasis formed by Control siRNA cells and no sign of tumor invasion and metastasis formed by Aurora‐A siRNA cells. Arrows indicate the presence of tumor invasion to the adjacent muscle tissues or metastatic tumor in tumor or lung slice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant (81021061, 81230047 and 30973401). The human ESCC cell line, KYSE150, was generously provided by Dr. Y Shimada of Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan.

Supplementary data 1.

1.1.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2014.08.002.

Jin Shunqian, Wang Xiaoxia, Tong Tong, Zhang Dongdong, Shi Ji, Chen Jie, Zhan Qimin, (2015), Aurora‐A enhances malignant development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) by phosphorylating β‐catenin, Molecular Oncology, 9, doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.08.002.

References

- Bienz, M. , 2005. beta-Catenin: a pivot between cell adhesion and Wnt signalling. Curr. Biol. 15, R64–R67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienz, M. , Clevers, H. , 2000. Linking colorectal cancer to Wnt signaling. Cell. 103, 311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff, J.R. , Anderson, L. , Zhu, Y. , Mossie, K. , Ng, L. , Souza, B. , Schryver, B. , Flanagan, P. , Clairvoyant, F. , Ginther, C. , Chan, C.S. , Novotny, M. , Slamon, D.J. , Plowman, G.D. , 1998. A homologue of Drosophila aurora kinase is oncogenic and amplified in human colorectal cancers. EMBO J. 17, 3052–3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briassouli, P. , Chan, F. , Savage, K. , Reis-Filho, J.S. , Linardopoulos, S. , 2007. A Aurora-A regulation of nuclear factor-kappaB signaling by phosphorylation of IkappaBalpha. Cancer Res. 67, 1689–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang, D. , Hawke, D. , Zheng, Y. , Xia, Y. , Meisenhelder, J. , Nika, H. , Mills, G.B. , Kobayashi, R. , Hunter, T. , Lu, Z. , 2007. Phosphorylation of beta-catenin by AKT promotes beta-catenin transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 11221–11229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, M. , Yakushijin, Y. , Ohtsuka, M. , Kakimoto, M. , Yasukawa, M. , Fujita, S. , 2003. Aurora2/BTAK/STK15 is involved in cell cycle checkpoint and cell survival of aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 121, 439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, S. , Kishida, S. , Yamamoto, H. , Murai, H. , Koyama, S. , Kikuchi, A. , 1998. Axin, a negative regulator of the Wnt signaling pathway, forms a complex with GSK-3beta and beta-catenin and promotes GSK-3beta-dependent phosphorylation of beta-catenin. EMBO J. 17, 1371–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng, Y.M. , Peng, S.Y. , Lin, C.Y. , Hsu, H.C. , 2004. Overexpression and amplification of Aurora-A in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 2065–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J. , Liu, R. , Tong, T. , Song, Y. , Jin, S. , Wu, M. , Zhan, Q. , 2007. Gadd45a regulates beta-catenin distribution and maintains cell-cell adhesion/contact. Oncogene. 26, 6396–6405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama, H. , Sasai, K. , Kawai, H. , Yuan, Z.M. , Bondaruk, J. , Suzuki, F. , Fujii, S. , Arlinghaus, R.B. , Czerniak, B.A. , Sen, S. , 2004. Phosphorylation by aurora kinase A induces Mdm2-mediated destabilization and inhibition of p53. Nat. Genet. 36, 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama, H. , Sen, S. , 2010. Aurora kinase inhibitors as anticancer molecules. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1799, 829–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, Y. , Senda, T. , Ishidate, T. , Koyama, R. , Morishita, T. , Iwayama, Y. , Higuchi, O. , Akiyama, T. , 2000. Asef, a link between the tumor suppressor APC and G-protein signaling. Science. 289, 1194–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D.C. , Du, X.L. , Wang, M.R. , 2009. Protein alterations in ESCC and clinical implications: a review. Dis. Esophagus. 22, 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q. , Kaneko, S. , Yang, L. , Feldman, R.I. , Nicosia, S.V. , Chen, J. , Cheng, J.Q. , 2004. Aurora-A abrogation of p53 DNA binding and transactivation activity by phosphorylation of serine 215. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52175–52182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin, P.J. , 1999. Beta-catenin signaling and cancer. Bioessays. 21, 1021–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neben, K. , Korshunov, A. , Benner, A. , Wrobel, G. , Hahn, M. , Kokocinski, F. , Golanov, A. , Joos, S. , Lichter, P. , 2004. Microarray-based screening for molecular markers in medulloblastoma revealed STK15 as independent predictor for survival. Cancer Res. 64, 3103–3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, W.J. , Nusse, R. , 2004. Convergence of Wnt, beta-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science. 303, 1483–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papkoff, J. , Aikawa, M. , 1998. WNT-1 and HGF regulate GSK3 beta activity and beta-catenin signaling in mammary epithelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 247, 851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y.J. , Chao, W.X. , Chiu, J.F. , 2012. An overview of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma proteomics. J. Proteomics. 75, 3129–3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito-Diaz, K. , Chen, T.W. , Wang, X. , Thorne, C.A. , Wallace, H.A. , Page-McCaw, A. , Lee, E. , 2013. The way Wnt works: components and mechanism. Growth Factors. 31, 1–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S. , Zhou, H. , Zhang, R.D. , Yoon, D.S. , Vakar-Lopez, F. , Ito, S. , Jiang, F. , Johnston, D. , Grossman, H.B. , Ruifrok, A.C. , Katz, R.L. , Brinkley, W. , Czerniak, B. , 2002. Amplification/overexpression of a mitotic kinase gene in human bladder cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 94, 1320–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, Y. , Imamura, M. , Wagata, T. , Yamaguchi, N. , Tobe, T. , 1992. Characterization of 21 newly established esophageal cancer cell lines. Cancer. 69, 277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, E. , Hashimoto, Y. , Ito, T. , Okumura, T. , Kan, T. , Watanabe, G. , Imamura, M. , Inazawa, J. , Shimada, Y. , 2005. The clinical significance of Aurora-A/STK15/BTAK expression in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 1827–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taurin, S. , Sandbo, N. , Qin, Y. , Browning, D. , Dulin, N.O. , 2006. Phosphorylation of beta-catenin by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9971–9976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, T. , Zhong, Y. , Kong, J. , Dong, L. , Song, Y. , Fu, M. , Liu, Z. , Wang, M. , Guo, L. , Lu, S. , Wu, M. , Zhan, Q. , 2004. Overexpression of Aurora-A contributes to malignant development of human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 7304–7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, H. , Kishida, S. , Kishida, M. , Ikeda, S. , Takada, S. , Kikuchi, A. , 1999. Phosphorylation of axin, a Wnt signal negative regulator, by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta regulates its stability. Biol. Chem. 274, 10681–10684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J. , Yue, W. , Zhu, M.J. , Sreejayan, N. , Du, M. , 2010. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) cross-talks with canonical Wnt signaling via phosphorylation of beta-catenin at Ser 552. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 395, 146–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C. , Liu, S. , Zhou, X. , Xue, L. , Quan, L. , Lu, N. , Zhang, G. , Bai, J. , Wang, Y. , Liu, Z. , Zhan, Q. , Zhu, H. , Xu, N. , 2005. Overexpression of human pituitary tumor transforming gene (hPTTG), is regulated by beta-catenin/TCF pathway in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer. 113, 891–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H. , Kuang, J. , Zhong, L. , Kuo, W.L. , Gray, J.W. , Sahin, A. , Brinkley, B.R. , Sen, S. , 1998. Tumour amplified kinase STK15/BTAK induces centrosome amplification, aneuploidy and transformation. Nat. Genet. 20, 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, G. , Wang, Y. , Huang, B. , Liang, J. , Ding, Y. , Xu, A. , Wu, W. , 2012. A Rac1/PAK1 cascade controls β-catenin activation in colon cancer cells. Oncogene. 31, 1001–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary Figure S1 Knockdown of Aurora‐A inhibits ESCC tumor invasion and metastasis. A) Western blot analysis of Aurora‐A expression in Aurora‐A siRNA and Control siRNA groups. B) The effect of Aurora‐A knockdown on cell migration and invasion ability in vitro. The results were from three separate experiments; bars, SD.*, P < 0.01. C) Aurora‐A Knockdown suppressed tumor growth in vivo. The xenograft tumor volume was measured at the indicated time points during the period of 12 weeks. D–F) Aurora‐A knockdown inhibited tumor cell invasion and metastasis in vivo. Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining sections of tumor invasion to the adjacent muscle tissues (D), lymph node (E) and lung (F) metastasis formed by Control siRNA cells and no sign of tumor invasion and metastasis formed by Aurora‐A siRNA cells. Arrows indicate the presence of tumor invasion to the adjacent muscle tissues or metastatic tumor in tumor or lung slice.