Abstract

Acid ceramidase (ASAH1) a key enzyme of sphingolipid metabolism converting pro‐apoptotic ceramide to sphingosine has been shown to be overexpressed in various cancers. We previously demonstrated higher expression of ASAH1 in ER positive compared to ER negative breast cancer. In the current study we performed subtype specific analyses of ASAH1 gene expression in invasive and non invasive breast cancer. We show that expression of ASAH1 is mainly associated with luminal A – like cancers which are known to have the best prognosis of all breast cancer subtypes. Moreover tumors with high ASAH1 expression among the other subtypes are also characterized by an improved prognosis. The good prognosis of tumors with high ASAH1 is independent of the type of adjuvant treatment in breast cancer and is also detected in non small cell lung cancer patients. Moreover, even in pre‐invasive DCIS of the breast ASAH1 is associated with a luminal phenotype and a reduced frequency of recurrences. Thus, high ASAH1 expression is generally associated with an improved prognosis in invasive breast cancer independent of adjuvant treatment and could also be valuable as prognostic factor for pre‐invasive DCIS.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Sphingolipids, Ceramide, Acid ceramidase, Prognosis, Ductal carcinoma in situ

Highlights

Acid ceramidase (ASAH1) is a key enzyme of sphingolipid metabolism.

ASAH1 is highly expressed in luminal A – like subtype of breast cancer.

ASAH1 expressing tumors show improved prognosis independent of adjuvant treatment.

Also in DCIS high ASAH1 is associated with a luminal phenotype.

ASAH1 may be a valuable prognostic marker in both DICS and early breast cancer.

1. Introduction

Sphingolipids represent a family of membrane lipids with highly particular functions. On one hand they contribute structurally to the cells membrane (Futerman and Hannun, 2004) but on the other hand they act as bioactive effectors regulating a variety of cellular functions (Zheng et al., 2006). Main players in sphingolipid metabolism are ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine‐1‐phosphate (Saddoughi et al., 2008; Gangoiti et al., 2010). Ceramide is metabolized by acid ceramidase (ASHA1) (Li et al., 1999) to sphingosine which is further converted into sphingosine‐1‐phosphate through sphingosine‐kinases (SPHK) (Pyne and Pyne, 2010). While ceramide exhibit pro‐apoptotic stimuli on cancer cells and normal tissue (Morad and Cabot, 2013), the counterpart sphingosine‐1‐phosphate functions as an anti‐apoptotic signal regulating proliferation, inflammation, angiogenesis and resistance to apoptotic cell death (Mao and Obeid, 2008; Ponnusamy et al., 2010). Therefore a concept termed sphingolipid rheostat has been proposed (Spiegel and Milstien, 2003). Following this concept the dynamic equilibrium between the different sphingolipid metabolites and balanced regulation of opposing signalling pathways is a crucial factor that determines the fate of cells (Ponnusamy et al., 2010; Ryland et al., 2011). Exogenous ceramide analoga affect this system in vitro and have therapeutic potential in various tumors (Canals et al., 2011; Barth et al., 2011) comprising breast cancer (Struckhoff et al., 2004; Flowers et al., 2012; Gouazé‐Andersson et al., 2011; Morad et al., 2012), prostate cancer (Holman et al., 2008; Norris et al., 2006; Saad et al., 2007), colon cancer (Dahm et al., 2008), head and neck cancer (Mehta et al., 2000; Elojeimy et al., 2007), leukaemia (Furlong et al., 2008), or pancreatic cancer (Jiang et al., 2011; Morad et al., 2013b). ASAH1 has been shown to be overexpressed in various cancer types (French et al., 2006), including head and neck cancer(Mehta et al., 2000), prostate cancer (Norris et al., 2006; Saad et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2009; Morad et al., 2013a; Mahdy, Ayman E M et al., 2009) and melanoma (Musumarra et al., 2003). Previously we found for sphingosine‐kinase‐1 (SPHK1) higher expression in ER negative breast cancer as well as a poor prognostic value (Ruckhäberle et al., 2008) but a predictive value for response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Ruckhäberle et al., 2013). In contrast, higher ASAH1 expression was found to be associated with ER positive breast cancer and an improved prognosis (Ruckhäberle et al., 2009a). Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease composed of at least four major subtypes which differ by expression of estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PgR) receptors, HER2, and proliferative status (Reis‐Filho and Pusztai, 2011; Goldhirsch et al., 2011; Prat et al., 2011). Current whole genome projects also suggest additional molecular stratification (Curtis et al., 2012; Karn, 2013; Koboldt et al., 2012; Banerji et al., 2012) and revealed that e.g. “basal‐like” breast cancer may be considered as a distinct disease more related to ovarian cancer than to other breast cancer subtypes (Koboldt et al., 2012). Therefore it is pivotal to perform gene expression analyses separately by breast cancer subtype to avoid rediscovering the well known differences between the subtypes (Prat et al., 2013, 2011, 2012, 2011, 2011, 2011).

In the current study we conducted subtype specific analyses of ASAH1 expression in invasive breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) on mRNA level and immunohistochemistry. Our results demonstrate that expression of ASAH1 is preferentially associated with luminal A – like cancers and an improved prognosis. This better prognosis was independent of the type of adjuvant treatment and was also detected in a cohort of non small cell lung cancer patients. High ASAH1 was also associated with luminal phenotype in DCIS and could be associated with a reduced frequency of recurrences in this early type of disease.

2. Materials and methods

All analyses in this study were performed according to the “REporting recommendations for tumour MARKer prognostic studies” (REMARK) (McShane et al., 2005; Simon et al., 2009) and the respective guidelines to microarray‐based studies for clinical outcomes (Dupuy and Simon, 2007).

2.1. Gene expression data

We used a previously described (Hanker et al., 2013b; Sänger et al., 2014) cohort of compiled Affymetrix gene expression data (U133A or U133Plus2.0 arrays) of 4467 breast cancer patients from 40 publicly available datasets (Supplementary Table S1). Affymetrix CEL files were processed with the MAS5.0 algorithm of the affy package (Gautier et al., 2004) of the Bioconductor software project (Gentleman et al., 2004). Data from each array were log2‐transformed, median‐centered, and expression values of all the probesets from the U133A array were multiplied by a scale factor S so that the magnitude (sum of the squares of the values) equals one. The bimodal distributions of ESR1, PgR, HER2, and OPG gene expression were used to derive cutoffs to differentiate high and low expression, or positive and negative status, respectively, as described previously (Karn et al., 2010). Two different methods were applied to define molecular subtypes of breast cancer. First, to approximate the intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer we used the simple method according to Hugh et al. (Hugh et al., 2009) which is based on the expression of single marker genes (ESR1, PgR, HER2, Ki67) to define TNBC‐, HER2‐, Luminal A‐, and Luminal B‐subtypes. For a distinction of Luminal A and Luminal B subgroups all 2884 ERpositive/HER2negative samples were selected and a median split according to Ki67 expression was performed. In addition all 106 ERpositive/HER2positive cases were also assigned to the Luminal B subtype according to this method (Hugh et al., 2009). As a second, alternative method for subtype determination, we applied a single sample predictor (SSP) (Weigelt et al., 2010) according to the centroid method using the gene set from Hu et al. (2006). The centroid analyses were performed separately in six larger datasets encompassing a total of 1142 samples. Respective subtype designations by both methods for each individual sample are given in Supplementary Table S2. Several different probesets for ASAH1 were available on the Affymetrix U133A microarray. We had previously shown that the highest consistency was found for probesets 210980_s_at and 213702_x_at (Ruckhäberle et al., 2009a). Again we verified this result in the current dataset (Supplementary Figure S1) and used probeset 210980_s_at for all subsequent analyses of ASAH1 expression. Affymetrix microarray data from ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) were obtained from a dataset published by Vincent‐Salomon et al. (Vincent‐Salomon et al., 2008) and were downloaded from caArray (https://array.nci.nih.gov/caarray/project/vince‐00013).

2.2. Statistical analysis

Chi‐Square and Fisher's Exact Test were used to determine significance of categorical variables. Kruskal–Wallis Test and Mann–Whitney U‐Test were used to analyze differences in continuous expression values between subtypes. Follow up information was available for 2794 of the 4467 invasive breast cancer samples. For 1463 samples the survival endpoint was relapse free survival (RFS) including local recurrences, for 1331 samples only distant metastasis free survival (DMFS) was available. In the conduct of the presented analysis event free survival (EFS) was calculated as preferentially corresponding to the RFS endpoint including local relapses, but measured with respect to the DMFS endpoint if RFS was not available. All results from survival analyses were verified by examining the effect of different endpoints in stratified analyses. Follow up data for those women in whom the envisaged end point was not reached were censored as of the last follow‐up date or at 120 months. Subjects with missing values were excluded from the analyses. We constructed Kaplan–Meier curves and used the log‐rank test to determine univariate significance of the variables. A Cox proportional‐hazards model was used to simultaneously examine the effects of multiple covariates on survival. The effect of each individual variable was assessed with the use of the Wald test and described by the hazard ratio, with a 95 percent confidence interval (95% CI). All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics Version 22 (IBM Corp.) and R 3.0.1 (www.r‐project.org). In addition, the online KM plotter database (Györffy et al., 2010) (http://www.kmplot.com) was also used for survival analysis in ER positive cohorts with different types of adjuvant treatment (Mihály et al., 2013).

2.3. Immunohistochemical analysis of ASAH1 expression

Tissue samples of 38 cases of pure DCIS were obtained from routine pathological procedures with IRB approval and informed consent. Histopathology sections stained with hematoxylin‐eosin were used for primary diagnosis and second reviewing (K.E.). After mounting on Superfrost Plus slides, paraffin sections (2 mm) were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated to water through a graduated ethanol series. For antigen retrieval, sections were incubated for 20 min in a microwave oven (800 W) using EDTA buffer (10 mmol/L; pH 8.0). Sections were incubated with a monoclonal anti‐ASAH1 antibody (Biozol Diagnostica, Germany; cat. no. H00000427‐M01, Clone2C9) at a 1:100 dilution for 1 h at room temperature. For negative controls, the primary antibody (Ab) was omitted. For secondary antibody incubation, the Dako REAL Detection System Alkaline Phosphatase (Dako, Denmark) was applied, following the instructions of the vendor. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Staining intensity was assigned semiquantitatively as 0, negative; 1, weak; 2, moderate; or 3, strong. The sample cohort were then dichotomized in low (0,1) or high (2,3) ASAH1 expression. All assessments were made blinded with respect to clinical patient data.

3. Results

3.1. ASAH1 gene expression is associated with Luminal A subtype of breast cancer

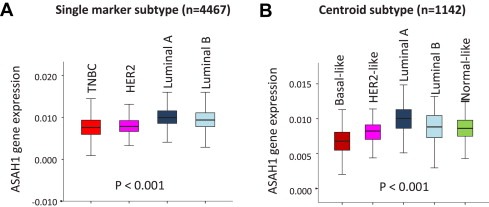

We analyzed Affymetrix microarray expression data of a combined cohort of 4467 primary invasive breast cancer samples compiled from 40 different datasets that we have described recently (Hanker et al., 2013b; Sänger et al., 2014). Clinical Parameters of the patients are given in Table 1. We first compared expression of ASAH1 gene among the different molecular subtypes of breast cancer. We used two alternative strategies to determine the molecular subtypes as described in detail in the Methods section: Either a single marker method according to Hugh et al. (Hugh et al., 2009) or the centroid method using the intrinsic gene set (Hu et al., 2006; Weigelt et al., 2010). Results according to the single marker method were available for all 4467 samples, the classification according to the centroid method for 1142 samples. Figure 1 shows that expression of ASAH1 differed between subtypes (P < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis Test). High expression of ASAH1 was observed in the luminal subtypes of breast cancer, especially in Luminal A samples, independently of the applied subtyping methodology. Low ASAH1 expression was detected in TNBC and basal‐like cancer while samples from the HER2‐like subgroup displayed intermediate expression.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 4467 primary invasive breast cancer samples with Affymetrix microarray data from 40 datasets.

| Parameter | Total | Low ASAH1 (n = 3350) | High ASAH1 (n = 1117) | P‐value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph node status | LNN | 2040 | 62.5% | 1625 | 64.0% | 415 | 57.1% | |

| N+ | 1225 | 37.5% | 913 | 36.0% | 312 | 42.9% | 0.001 | |

| Age | Age > 50 | 1908 | 61.1% | 1349 | 56.7% | 559 | 75.0% | |

| Age ≤ 50 | 1217 | 38.9% | 1031 | 43.3% | 186 | 25.0% | 0.001 | |

| Tumor size | ≤2 cm | 358 | 20.3% | 308 | 20.3% | 50 | 20.6% | |

| >2 cm | 1403 | 79.7% | 1210 | 79.7% | 193 | 79.4% | n.s. | |

| Grade | G3 | 1524 | 49.2% | 1285 | 54.0% | 239 | 33.2% | |

| G1 & G2 | 1575 | 50.8% | 1095 | 46.0% | 480 | 66.8% | <0.001 | |

| ER status | Positive | 2990 | 66.9% | 2024 | 60.4% | 966 | 86.5% | |

| Negative | 1477 | 33.1% | 1326 | 39.6% | 151 | 13.5% | <0.001 | |

| PgR status | Positive | 2466 | 55.2% | 1669 | 49.8% | 797 | 71.4% | |

| Negative | 2001 | 44.8% | 1681 | 50.2% | 320 | 28.6% | <0.001 | |

| HER2 status | Positive | 589 | 13.2% | 518 | 15.5% | 71 | 6.4% | |

| Negative | 3878 | 86.8% | 2832 | 84.5% | 1046 | 93.6% | <0.001 | |

Figure 1.

ASAH1 gene expression in different molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Box plots of ASAH1 gene expression measured by Affymetrix microarray (probeset 210980_s_at) are shown for molecular subtypes of breast cancer defined by two alternative approaches. In (A) subtypes classification was either performed using a single marker method according to Hugh et al. (Hugh et al., 2009) among 4467 pre‐therapeutic invasive breast cancer samples from 40 datasets. In (B) the centroid method using the intrinsic gene set (Weigelt et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2006) was applied to 1142 samples from six large datasets. Highest expression of ASAH1 was detected in the Luminal A subtype of breast cancer by both methods. P‐Values are given according to Kruskal–Wallis Test for difference in expression between subtypes.

3.2. High ASAH1 expression correlates with better prognosis

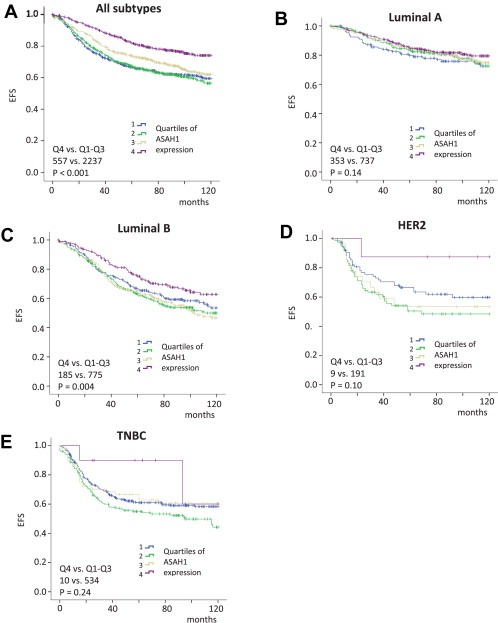

We further studied the prognostic value of ASHA1 expression in the tumor for relapse free survival of the patient. Follow up data were available for 2794 of the 4467 samples. Figure 2A shows the Kaplan–Meier analysis of the 2794 patients stratified according to quartiles of ASAH1 expression. An improved survival was detected for patients within the highest quartile of ASAH1 expression (P < 0.001). Table 1 also presents clinical parameters of patients from the highest quartile of ASAH1 expression compared to those with low ASAH1 expression. Patients with high ASAH1 are characterized by a higher proportion of ER positive, PgR positive, and lymph node positive patients while those with low ASAH1 encompass more grade 3 and HER2 positive tumors, and patients with young age. The difference in survival in Figure 2A seem to reflect that high expression of ASAH1 was observed in the luminal subtypes of breast cancer (see Figure 1 above) which are known to have a better prognosis than TNBC and HER2‐like subtypes. We therefore also repeated the Kaplan–Meier analysis separately for each breast cancer subtype in Figure 2B–E. A significant difference in prognosis was detected mainly within the Luminal B subtype (P = 0.004; Figure 2C) but not for Luminal A tumors (P = 0.14; Figure 2B). As shown in Figure 2D,E only very few patients in the TNBC and HER2‐like subgroups displayed strong ASAH1 expression (highest quartile). The better survival of these only 9 and 10 patients, respectively, was not statistically significant (P = 0.10 and P = 0.24; Figures 2D and 2E, respectively).

Figure 2.

Prognostic value of ASAH1 expression in molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Kaplan–Meier analysis of event free survival of breast cancer patients according to quartiles of ASAH1 gene expression among all samples is given in panel A. Separate analysis for the different molecular subtypes of breast cancer defined according to the single marker method are given in panels B–E. In each graph sample numbers and P‐values of log‐rank test are provided for the comparison of the upper quartile (Q4) against the rest of the samples (Q1–Q3).

Table 2 presents the results of a multivariate Cox regression analysis of survival including ASAH1, the molecular subtype classification, and all clinical parameters in 870 patients for which all parameters were available. In this analysis only the molecular subtype of the tumor remained significant while ASAH1 only showed a trend towards significance (P = 0.090). In an additional analysis, in which we replaced molecular subtype classification by ER, PgR, and HER2 receptor status, only PgR status remained significant (P = 0.005) while both ASAH1 and ER displayed only a strong trend to significance (P = 0.063 for both; Supplementary Table S3).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of survival according to ASAH1 expression and molecular subtypes and standard parameters.

| Parameter | Numbersa | HR | 95% CI | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASAH1 (High vs. Low) | 107 vs. 763 | 0.71 | 0.47–1.06 | 0.090 |

| Lymph node status (LNN vs. N+) | 662 vs. 208 | 0.81 | 0.61–1.08 | 0.15 |

| Age (>50 vs. ≤50) | 466 vs. 404 | 1.13 | 0.90–1.43 | 0.29 |

| tumor size (≤1 cm vs. >1 cm) | 238 vs. 632 | 0.91 | 0.69–1.20 | 0.50 |

| Histological grading (G3 vs. G1&G2) | 484 vs. 386 | 1.05 | 0.82–1.34 | 0.71 |

| Molecular subtype: TNBC | 261 | <0.001 | ||

| HER2 | 91 | 0.94 | 0.61–1.44 | 0.77 |

| LumA | 255 | 0.68 | 0.48–0.97 | 0.031 |

| LumB | 263 | 1.40 | 1.05–1.86 | 0.023 |

Information on all six parameters was available for 870 of the 2590 samples with follow up data.

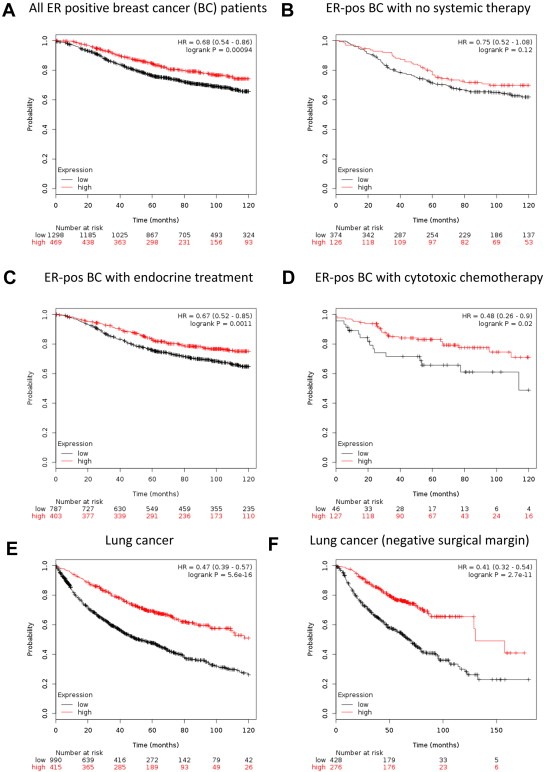

We then looked within the luminal subtype for possible relationships of different treatments and the prognostic value of ASAH1 expression. For this purpose we applied an updated version of the KM plotter database (Györffy et al., 2010) including adjuvant treatment information (Mihály et al., 2013). As demonstrated in Figure 3A–D the positive prognostic effect of high ASAH1 expression was detected among all ER positive patients, irrespective of whether they obtained endocrine treatment, cytotoxic chemotherapy, or no adjuvant therapy. Interestingly, using a recently developed similar database for lung cancer (Győrffy et al., 2013) we also detected a strong prognostic value of ASAH1 expression in non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) as shown in Figure 3E–F.

Figure 3.

Prognostic value of ASAH1 in luminal breast cancer according to treatment and NSCLC. The KM‐plotter (Györffy et al., 2010) database was used to analyze the prognostic value of ASAH1 expression in different subsets of ER positive breast cancers according to adjuvant treatment in panels A–D with either all ER positive BC patients (A), ER positive BC patients without any systemic therapy (B), and ER positive BC patients with only endocrine treatment (B) or chemotherapy (C). In addition the prognostic effect of ASAH1 expression in non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is shown for all patients (E) or those patients with negative surgical margin (F).

3.3. ASAH1 expression in luminal subtype of ductal carcinoma in situ

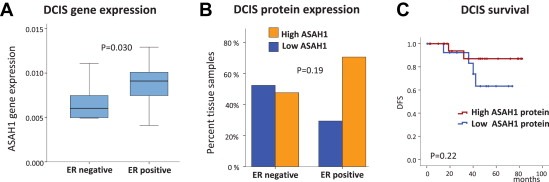

We next studied microarray data from non invasive ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). We intended to analyze whether high AHSAH1 expression is already detectable and also associated with a luminal subtype in this pre‐invasive form of disease. We used a published Affymetrix dataset encompassing a total of 26 DCIS cases, 18 of which are luminal (ER positive) and 8 non luminal (HER2‐positive/ER negative) (Vincent‐Salomon et al., 2008). ASAH1 expression clearly differed between those two groups of DCIS with high expression in the luminal subtype (Figure 4A, P = 0.030, Mann–Whitney U Test). We then set out to verify this result on the level of protein expression by using immuno‐histo‐chemistry (IHC). We performed IHC of ASAH1 and ER on 38 cases of DCIS from our own institution. As shown in Figure 4B we also detected by this method a trend for higher ASAH1 expression in the ER positive luminal subtype of DCIS (P = 0.19). When analyzing the available follow up from this dataset we observed less recurrences in the group of DCIS with high ASAH1 expression by IHC but obtained no statistical significance in this small group of 21 patients (P = 0.22, Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

ASAH1 expression in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast. A)ASAH1 gene expression in ductal carcinoma in situ (n = 26) of luminal (ER positive) or non‐luminal (ER negative) type from a published microarray dataset (P = 0.030; Mann–Whitney U‐Test). B) Differences in ER‐status in DCIS samples characterized for ASAH1 by immunohistochemistry (n = 38; P = 0.19, Fishers's Exact Test). C) Kaplan–Meier analysis of disease free survival after DCIS characterized by ASAH1 immunohistochemistry (n = 21; P = 0.22, Log–Rank Test).

4. Discussion

In previous studies we reported increased expression of ASAH1 in ER positive breast tumors and an improved survival of those cancers (Ruckhäberle et al., 2009, 2008). In our present study we have considerably enlarged sample size, analyzed ASAH1 expression in different molecular subtypes of breast cancer and have also extended our observations to pre‐invasive breast tumors of ductal carcinoma in situ. Beside breast cancer acid ceramidase (ASAH1) has been reported to be involved in several other types of cancer as prostate cancer (Holman et al., 2008; Saad et al., 2007; Mahdy, Ayman E M et al., 2009), leukaemia (Furlong et al., 2008), colon cancer (Selzner et al., 2001), and head and neck cancer (Elojeimy et al., 2007). But data on the prognostic value of differences in ASAH1 expression are relatively scarce. We previously detected increased levels of different ceramids in human breast cancer tissues compared to benign samples and found a positive association with the ER status (Schiffmann et al., 2009). In contrast, overexpression of ASAH1 has been shown to reduce ceramide and increase S1P levels, which has been related to the stimulation of cancer progression (Huwiler and Pfeilschifter, 2006; Canals et al., 2011). In this regard both the correlation of higher ASAH1 expression with ER positive breast cancer and with a better prognosis is rather counterintuitive. However, sphingolipid metabolism pathways are known to be highly complex and interconnected (Futerman and Hannun, 2004; Zheng et al., 2006; Saddoughi et al., 2008; Gangoiti et al., 2010; Morad and Cabot, 2013). In addition to ASAH1 several other enzymes as e.g. ceramide synthases can contribute to the cellular ceramide level and the expression of these enzymes also differed significantly between ER positive and ER negative breast tumors (Ruckhäberle et al., 2009, 2008, 2009c). Interestingly, we did also detect a better prognosis for high ASAH1 gene expression in a cohort of non small cell lung cancer patients in our present study (Figure 3E,F). Moreover, immunohistochemical analyses of epithelial ovarian cancer suggested that high ASAH1 expression identifies a subgroup of patients with a better outcome (Hanker et al., 2013a). Our cohort of 39 DCIS patients with both immunohistochemical data and follow up may have been too small to detect a similar result with statistical significance (P = 0.22; Figure 4C). Still, all these results seem to associate a higher ASAH1 expression with improved patient prognosis in different types of cancer. In vitro studies demonstrate that ASAH1 expression can be induced by radiation and ASAH1 overexpression increased chemotherapy resistance of cancer cells (Saad et al., 2007; Mahdy, Ayman E M et al., 2009). On the other hand tamoxifen downregulates ASAH1 protein in different cancer cell types (Morad et al., 2013a). Detailed data on radiotherapy was not available for our patient cohort. However, we observed the positive prognostic value of ASAH1 expression independent of the type of adjuvant treatment that breast cancer patients had received (chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or no adjuvant treatment; Figure 3B,C,D). Nevertheless, this observation may not argue against e.g. an influence of ASAH1 on chemotherapy resistance since it could have both a prognostic and a predictive role as we e.g. have previously shown for SPHK1 (Ruckhäberle et al., 2013, 2008). We detected a correlation of ASAH1 expression with a luminal ER positive differentiation already among pre‐invasive forms of ductual carcinoma in situ of the breast (Figure 4A,B). Clearly, much larger cohorts are needed to verify a potential association of high ASAH1 and a reduced frequency of recurrences in this early type of disease. But since current prognostic factors for DCIS are often unsatisfactory this result could be of clinical interest. A strength of our study is a large sample size but limitations include the retrospective design of the analysis and the availability of only mRNA expression data for most of the samples. Thus our study could miss potential regulation of protein expression and has no data on the actual level of different sphingolipids in the biological samples. All samples were pretherapeutic biopsies, so possible influences of treatment on ASAH1 expression could not be observed.

In conclusion we demonstrate that ASAH1 is preferentially associated with low risk luminal A breast cancer. High ASAH1 expression is overall associated with an improved prognosis in invasive breast cancer independent of adjuvant treatment and may also be a prognostic factor for pre‐invasive DCIS.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the H.W. & J. Hector‐Stiftung, Mannheim; the Margarete Bonifer‐Stiftung, Bad Soden; National Cancer Center, New York; and the BANSS‐Stiftung, Biedenkopf.

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Supplementary Figure S1: Correlation of AHSA1 expression from different Affymetrix probesets Scatter plot of Affymetrix data for probesets 210980_s_at and 213702_x_at from all 4467 patients.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

We thank Katerina Brinkmann and Samira Adel for expert technical assistance.

1.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2014.07.016.

Sänger Nicole, Ruckhäberle Eugen, Györffy Balazs, Engels Knut, Heinrich Tomas, Fehm Tanja, Graf Anna, Holtrich Uwe, Becker Sven, Karn Thomas, (2015), Acid ceramidase is associated with an improved prognosis in both DCIS and invasive breast cancer, Molecular Oncology, 9, doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.07.016.

References

- Banerji, S. , Cibulskis, K. , Rangel-Escareno, C. , Brown, K.K. , Carter, S.L. , Frederick, A.M. , Lawrence, M.S. , Sivachenko, A.Y. , Sougnez, C. , Zou, L. , Cortes, M.L. , Fernandez-Lopez, J.C. , Peng, S. , Ardlie, K.G. , Auclair, D. , 2012. Sequence analysis of mutations and translocations across breast cancer subtypes. Nature. 486, 405–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth, B.M. , Cabot, M.C. , Kester, M. , 2011. Ceramide-based therapeutics for the treatment of cancer. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 11, 911–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals, D. , Perry, D.M. , Jenkins, R.W. , Hannun, Y.A. , 2011. Drug targeting of sphingolipid metabolism: sphingomyelinases and ceramidases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 163, 694–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, C. , Shah, S.P. , Chin, S.-F. , Turashvili, G. , Rueda, O.M. , Dunning, M.J. , Speed, D. , Lynch, A.G. , Samarajiwa, S. , Yuan, Y. , Gräf, S. , Ha, G. , Haffari, G. , Bashashati, A. , Russell, R. , 2012. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 486, 346–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahm, F. , Bielawska, A. , Nocito, A. , Georgiev, P. , Szulc, Z.M. , Bielawski, J. , Jochum, W. , Dindo, D. , Hannun, Y.A. , Clavien, P.-A. , 2008. Mitochondrially targeted ceramide LCL-30 inhibits colorectal cancer in mice. Br. J. Cancer. 98, 98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy, A. , Simon, R.M. , 2007. Critical review of published microarray studies for cancer outcome and guidelines on statistical analysis and reporting. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 99, 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elojeimy, S. , Liu, X. , McKillop, J.C. , El-Zawahry, A.M. , Holman, D.H. , Cheng, J.Y. , Meacham, W.D. , Mahdy, A.E. , Saad, A.F. , Turner, L.S. , Cheng, J. , A Day, T. , Dong, J.-Y. , Bielawska, A. , Hannun, Y.A. , Norris, J.S. , 2007. Role of acid ceramidase in resistance to FasL: therapeutic approaches based on acid ceramidase inhibitors and FasL gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 15, 1259–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers, M. , Fabriás, G. , Delgado, A. , Casas, J. , Abad, J.L. , Cabot, M.C. , 2012. C6-ceramide and targeted inhibition of acid ceramidase induce synergistic decreases in breast cancer cell growth. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 133, 447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French, K.J. , Upson, J.J. , Keller, S.N. , Zhuang, Y. , Yun, J.K. , Smith, C.D. , 2006. Antitumor activity of sphingosine kinase inhibitors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 318, 596–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, S.J. , Ridgway, N.D. , Hoskin, D.W. , 2008. Modulation of ceramide metabolism in T-leukemia cell lines potentiates apoptosis induced by the cationic antimicrobial peptide bovine lactoferricin. Int. J. Oncol. 32, 537–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futerman, A.H. , Hannun, Y.A. , 2004. The complex life of simple sphingolipids. EMBO Rep. 5, 777–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangoiti, P. , Camacho, L. , Arana, L. , Ouro, A. , Granado, M.H. , Brizuela, L. , Casas, J. , Fabriás, G. , Abad, J.L. , Delgado, A. , Gómez-Muñoz, A. , 2010. Control of metabolism and signaling of simple bioactive sphingolipids: implications in disease. Prog. Lipid Res. 49, 316–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier, L. , Cope, L. , Bolstad, B.M. , Irizarry, R.A. , 2004. affy–analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 20, 307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman, R.C. , Carey, V.J. , Bates, D.M. , Bolstad, B. , Dettling, M. , Dudoit, S. , Ellis, B. , Gautier, L. , Ge, Y. , Gentry, J. , Hornik, K. , Hothorn, T. , Huber, W. , Iacus, S. , Irizarry, R. , 2004. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5, R80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldhirsch, A. , Wood, W.C. , Coates, A.S. , Gelber, R.D. , Thurlimann, B. , Senn, H.-J. , 2011. Strategies for subtypes–dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2011. Ann. Oncol. 22, 1736–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouazé-Andersson, V. , Flowers, M. , Karimi, R. , Fabriás, G. , Delgado, A. , Casas, J. , Cabot, M.C. , 2011. Inhibition of acid ceramidase by a 2-substituted aminoethanol amide synergistically sensitizes prostate cancer cells to N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) retinamide. Prostate. 71, 1064–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Györffy, B. , Lanczky, A. , Eklund, A.C. , Denkert, C. , Budczies, J. , Li, Q. , Szallasi, Z. , 2010. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 123, 725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Győrffy, B. , Surowiak, P. , Budczies, J. , Lánczky, A. , 2013. Online survival analysis software to assess the prognostic value of biomarkers using transcriptomic data in non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 8, e82241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanker, L.C. , Karn, T. , Holtrich, U. , Gätje, R. , Rody, A. , Heinrich, T. , Ruckhäberle, E. , Engels, K. , 2013. Acid ceramidase (AC)–a key enzyme of sphingolipid metabolism–correlates with better prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 32, 249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanker, L.C. , Rody, A. , Holtrich, U. , Pusztai, L. , Ruckhaeberle, E. , Liedtke, C. , Ahr, A. , Heinrich, T.M. , Sänger, N. , Becker, S. , Karn, T. , 2013. Prognostic evaluation of the B cell/IL-8 metagene in different intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 137, 407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman, D.H. , Turner, L.S. , El-Zawahry, A. , Elojeimy, S. , Liu, X. , Bielawski, J. , Szulc, Z.M. , Norris, K. , Zeidan, Y.H. , Hannun, Y.A. , Bielawska, A. , Norris, J.S. , 2008. Lysosomotropic acid ceramidase inhibitor induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 61, 231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z. , Fan, C. , Oh, D.S. , Marron, J.S. , He, X. , Qaqish, B.F. , Livasy, C. , Carey, La , Reynolds, E. , Dressler, L. , Nobel, A. , Parker, J. , Ewend, M.G. , Sawyer, L.R. , Wu, J. , 2006. The molecular portraits of breast tumors are conserved across microarray platforms. BMC Genomics. 7, 96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugh, J. , Hanson, J. , Cheang, M.C.U. , Nielsen, T.O. , Perou, C.M. , Dumontet, C. , Reed, J. , Krajewska, M. , Treilleux, I. , Rupin, M. , Magherini, E. , Mackey, J. , Martin, M. , Vogel, C. , 2009. Breast cancer subtypes and response to docetaxel in node-positive breast cancer: use of an immunohistochemical definition in the BCIRG 001 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 1168–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huwiler, A. , Pfeilschifter, J. , 2006. Altering the sphingosine-1-phosphate/ceramide balance: a promising approach for tumor therapy. Curr. Pharm. Des. 12, 4625–4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y. , DiVittore, N.A. , Kaiser, J.M. , Shanmugavelandy, S.S. , Fritz, J.L. , Heakal, Y. , Tagaram, Hephzibah Rani, S. , Cheng, H. , Cabot, M.C. , Staveley-O'Carroll, K.F. , Tran, M.A. , Fox, T.E. , Barth, B.M. , Kester, M. , 2011. Combinatorial therapies improve the therapeutic efficacy of nanoliposomal ceramide for pancreatic cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 12, 574–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karn, T. , 2013. High-throughput gene expression and mutation profiling: current methods and future perspectives. Breast Care (Basel). 8, 401–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karn, T. , Metzler, D. , Ruckhäberle, E. , Hanker, L. , Gätje, R. , Solbach, C. , Ahr, A. , Schmidt, M. , Holtrich, U. , Kaufmann, M. , Rody, A. , 2010. Data-driven derivation of cutoffs from a pool of 3,030 affymetrix arrays to stratify distinct clinical types of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 120, 567–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karn, T. , Pusztai, L. , Holtrich, U. , Iwamoto, T. , Shiang, C.Y. , Schmidt, M. , Müller, V. , Solbach, C. , Gaetje, R. , Hanker, L. , Ahr, A. , Liedtke, C. , Ruckhäberle, E. , Kaufmann, M. , Rody, A. , 2011. Homogeneous datasets of triple negative breast cancers enable the identification of novel prognostic and predictive signatures. PLoS ONE. 6, e28403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karn, T. , Pusztai, L. , Ruckhäberle, E. , Liedtke, C. , Müller, V. , Schmidt, M. , Metzler, D. , Wang, J. , Coombes, K.R. , Gätje, R. , Hanker, L. , Solbach, C. , Ahr, A. , Holtrich, U. , Rody, A. , Kaufmann, M. , 2012. Melanoma antigen family A identified by the bimodality index defines a subset of triple negative breast cancers as candidates for immune response augmentation. Eur. J. Cancer. 48, 12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt, D.C. , Fulton, R.S. , McLellan, M.D. , Schmidt, H. , Kalicki-Veizer, J. , McMichael, J.F. , Fulton, L.L. , Dooling, D.J. , Ding, L. , Mardis, E.R. , Wilson, R.K. , Ally, A. , Balasundaram, M. , Butterfield, Y.S.N. , Carlsen, R. , 2012. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 490, 61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.M. , Park, J.H. , He, X. , Levy, B. , Chen, F. , Arai, K. , Adler, D.A. , Disteche, C.M. , Koch, J. , Sandhoff, K. , Schuchman, E.H. , 1999. The human acid ceramidase gene (ASAH): structure, chromosomal location, mutation analysis, and expression. Genomics. 62, 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. , Cheng, J.C. , Turner, L.S. , Elojeimy, S. , Beckham, T.H. , Bielawska, A. , Keane, T.E. , Hannun, Y.A. , Norris, J.S. , 2009. Acid ceramidase upregulation in prostate cancer: role in tumor development and implications for therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 13, 1449–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdy, Ayman E.M. , Cheng, J.C. , Li, J. , Elojeimy, S. , Meacham, W.D. , Turner, L.S. , Bai, A. , Gault, C.R. , McPherson, A.S. , Garcia, N. , Beckham, T.H. , Saad, A. , Bielawska, A. , Bielawski, J. , Hannun, Y.A. , Keane, T.E. , Taha, M.I. , Hammouda, H.M. , Norris, J.S. , Liu, X. , 2009. Acid ceramidase upregulation in prostate cancer cells confers resistance to radiation: AC inhibition, a potential radiosensitizer. Mol. Ther. 17, 430–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao, C. , Obeid, L.M. , 2008. Ceramidases: regulators of cellular responses mediated by ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1781, 424–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShane, L.M. , Altman, D.G. , Sauerbrei, W. , Taube, S.E. , Gion, M. , Clark, G.M. , Statistics Subcommittee of the NCI-EORTC Working Group on Cancer Diagnostics2005. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 9067–9072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S. , Blackinton, D. , Omar, I. , Kouttab, N. , Myrick, D. , Klostergaard, J. , Wanebo, H. , 2000. Combined cytotoxic action of paclitaxel and ceramide against the human Tu138 head and neck squamous carcinoma cell line. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 46, 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihály, Z. , Kormos, M. , Lánczky, A. , Dank, M. , Budczies, J. , Szász, M.A. , Győrffy, B. , 2013. A meta-analysis of gene expression-based biomarkers predicting outcome after tamoxifen treatment in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 140, 219–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad, Samy A.F. , Cabot, M.C. , 2013. Ceramide-orchestrated signalling in cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 13, 51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad, Samy A.F. , Levin, J.C. , Tan, S.-F. , Fox, T.E. , Feith, D.J. , Cabot, M.C. , 2013. Novel off-target effect of tamoxifen–inhibition of acid ceramidase activity in cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1831, 1657–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad, Samy A.F. , Messner, M.C. , Levin, J.C. , Abdelmageed, N. , Park, H. , Merrill, A.H. , Cabot, M.C. , 2013. Potential role of acid ceramidase in conversion of cytostatic to cytotoxic end-point in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 71, 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad, Samy A.F. , Levin, J.C. , Shanmugavelandy, S.S. , Kester, M. , Fabrias, G. , Bedia, C. , Cabot, M.C. , 2012. Ceramide–antiestrogen nanoliposomal combinations–novel impact of hormonal therapy in hormone-insensitive breast cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 11, 2352–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musumarra, G. , Barresi, V. , Condorelli, D.F. , Scirè, S. , 2003. A bioinformatic approach to the identification of candidate genes for the development of new cancer diagnostics. Biol. Chem. 384, 321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris, J.S. , Bielawska, A. , Day, T. , El-Zawahri, A. , ElOjeimy, S. , Hannun, Y. , Holman, D. , Hyer, M. , Landon, C. , Lowe, S. , Dong, J.Y. , McKillop, J. , Norris, K. , Obeid, L. , Rubinchik, S. , Tavassoli, M. , Tomlinson, S. , Voelkel-Johnson, C. , Liu, X. , 2006. Combined therapeutic use of AdGFPFasL and small molecule inhibitors of ceramide metabolism in prostate and head and neck cancers: a status report. Cancer Gene Ther. 13, 1045–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnusamy, S. , Meyers-Needham, M. , Senkal, C.E. , Saddoughi, S.A. , Sentelle, D. , Selvam, S.P. , Salas, A. , Ogretmen, B. , 2010. Sphingolipids and cancer: ceramide and sphingosine-1-phosphate in the regulation of cell death and drug resistance. Future Oncol. 6, 1603–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prat, A. , Ellis, M.J. , Perou, C.M. , 2011. Practical implications of gene-expression-based assays for breast oncologists. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 9, 48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne, N.J. , Pyne, S. , 2010. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 10, 489–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis-Filho, J.S. , Pusztai, L. , 2011. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: classification, prognostication, and prediction. Lancet. 378, 1812–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rody, A. , Karn, T. , Liedtke, C. , Pusztai, L. , Ruckhaeberle, E. , Hanker, L. , Gaetje, R. , Solbach, C. , Ahr, A. , Metzler, D. , Schmidt, M. , Müller, V. , Holtrich, U. , Kaufmann, M. , 2011. A clinically relevant gene signature in triple negative and basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 13, R97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckhäberle, E. , Holtrich, U. , Engels, K. , Hanker, L. , Gätje, R. , Metzler, D. , Karn, T. , Kaufmann, M. , Rody, A. , 2009. Acid ceramidase 1 expression correlates with a better prognosis in ER-positive breast cancer. Climacteric. 12, 502–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckhäberle, E. , Karn, T. , Denkert, C. , Loibl, S. , Ataseven, B. , Reimer, T. , Becker, S. , Holtrich, U. , Rody, A. , Darb-Esfahani, S. , Nekljudovax, V. , Minckwitz, G. von , 2013. Predictive value of sphingosine kinase 1 expression inneoadjuvant treatment of breast cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 139, 1681–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckhäberle, E. , Karn, T. , Hanker, L. , Gätje, R. , Metzler, D. , Holtrich, U. , Kaufmann, M. , Rody, A. , 2009. Prognostic relevance of glucosylceramide synthase (GCS) expression in breast cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 135, 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckhäberle, E. , Karn, T. , Rody, A. , Hanker, L. , Gätje, R. , Metzler, D. , Holtrich, U. , Kaufmann, M. , 2009. Gene expression of ceramide kinase, galactosyl ceramide synthase and ganglioside GD3 synthase is associated with prognosis in breast cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 135, 1005–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckhäberle, E. , Rody, A. , Engels, K. , Gaetje, R. , Minckwitz, G. , von, Schiffmann, S. , Grösch, S. , Geisslinger, G. , Holtrich, U. , Karn, T. , Kaufmann, M. , 2008. Microarray analysis of altered sphingolipid metabolism reveals prognostic significance of sphingosine kinase 1 in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 112, 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryland, L.K. , Fox, T.E. , Liu, X. , Loughran, T.P. , Kester, M. , 2011. Dysregulation of sphingolipid metabolism in cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 11, 138–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad, A.F. , Meacham, W.D. , Bai, A. , Anelli, V. , Elojeimy, S. , Mahdy, Ayman E.M. , Turner, L.S. , Cheng, J. , Bielawska, A. , Bielawski, J. , Keane, T.E. , Obeid, L.M. , Hannun, Y.A. , Norris, J.S. , Liu, X. , 2007. The functional effects of acid ceramidase overexpression in prostate cancer progression and resistance to chemotherapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 6, 1455–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saddoughi, S.A. , Song, P. , Ogretmen, B. , 2008. Roles of bioactive sphingolipids in cancer biology and therapeutics. Subcell. Biochem. 49, 413–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sänger, N. , Ruckhäberle, E. , Bianchini, G. , Heinrich, T. , Milde-Langosch, K. , Müller, V. , Rody, A. , Solomayer, E.F. , Fehm, T. , Holtrich, U. , Becker, S. , Karn, T. , 2014 April 15. OPG and PgR show similar cohort specific effects as prognostic factors in ER positive breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.04.003 pii: S1574-7891(14)00080-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffmann, S. , Sandner, J. , Birod, K. , Wobst, I. , Angioni, C. , Ruckhäberle, E. , Kaufmann, M. , Ackermann, H. , Lötsch, J. , Schmidt, H. , Geisslinger, G. , Grösch, S. , 2009. Ceramide synthases and ceramide levels are increased in breast cancer tissue. Carcinogenesis. 30, 745–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzner, M. , Bielawska, A. , Morse, M.A. , Rüdiger, H.A. , Sindram, D. , Hannun, Y.A. , Clavien, P.A. , 2001. Induction of apoptotic cell death and prevention of tumor growth by ceramide analogues in metastatic human colon cancer. Cancer Res. 61, 1233–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon, R.M. , Paik, S. , Hayes, D.F. , 2009. Use of archived specimens in evaluation of prognostic and predictive biomarkers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 101, 1446–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel, S. , Milstien, S. , 2003. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: an enigmatic signalling lipid. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struckhoff, A.P. , Bittman, R. , Burow, M.E. , Clejan, S. , Elliott, S. , Hammond, T. , Tang, Y. , Beckman, B.S. , 2004. Novel ceramide analogs as potential chemotherapeutic agents in breast cancer. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 309, 523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent-Salomon, A. , Lucchesi, C. , Gruel, N. , Raynal, V. , Pierron, G. , Goudefroye, R. , Reyal, F. , Radvanyi, F. , Salmon, R. , Thiery, J.-P. , Sastre-Garau, X. , Sigal-Zafrani, B. , Fourquet, A. , Delattre, O. , 2008. Integrated genomic and transcriptomic analysis of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 1956–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigelt, B. , Mackay, A. , A'hern, R. , Natrajan, R. , Tan, D.S.P. , Dowsett, M. , Ashworth, A. , Reis-Filho, J.S. , 2010. Breast cancer molecular profiling with single sample predictors: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 11, 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigelt, B. , Pusztai, L. , Ashworth, A. , Reis-Filho, J.S. , 2011. Challenges translating breast cancer gene signatures into the clinic. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 9, 58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W. , Kollmeyer, J. , Symolon, H. , Momin, A. , Munter, E. , Wang, E. , Kelly, S. , Allegood, J.C. , Liu, Y. , Peng, Q. , Ramaraju, H. , Sullards, M.C. , Cabot, M. , Merrill, A.H. , 2006. Ceramides and other bioactive sphingolipid backbones in health and disease: lipidomic analysis, metabolism and roles in membrane structure, dynamics, signaling and autophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1758, 1864–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Supplementary Figure S1: Correlation of AHSA1 expression from different Affymetrix probesets Scatter plot of Affymetrix data for probesets 210980_s_at and 213702_x_at from all 4467 patients.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data