Abstract

The recently developed anti‐androgen enzalutamide also known as (MDV3100) has the advantage to prolong by 4.8 months the survival of castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) patients. However, the mechanisms behind the potential side effects involving the induction of the prostate cancer (PCa) neuroendocrine (NE) differentiation remain unclear. Here we found PCa cells could recruit more mast cells than normal prostate epithelial cells, and enzalutamide (or casodex) treatment could further increase such recruitment that resulted in promoting the PCa NE differentiation. Mechanism dissection found infiltrated mast cells could function through positive feedback to enhance PCa to recruit more mast cells via modulation of the androgen receptor (AR) → cytokines IL8 signals, and interruption by AR‐siRNA or neutralizing anti‐IL8 antibody could partially reverse the recruitment of mast cells. Importantly, targeting the PCa androgens/AR signals with AR‐siRNA or enzalutamide (or casodex) also increased PCa NE differentiation via modulation of the miRNA32 expression, and adding miRNA32 inhibitor reversed the AR‐siRNA‐ or enzalutamide‐enhanced NE differentiation. Together, these results not only identified a new signal via infiltrated mast cells → PCa AR → miRNA32 to increase PCa NE differentiation, it also pointed out the potential unwanted side effects of enzalutamide (or casodex) to increase PCa NE differentiation. Targeting these newly identified signals, including AR, IL8, or miRNA32, may help us to better suppress PCa NE differentiation that is induced during ADT with anti‐androgen enzalutamide (or casodex) treatment.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Mast cells, IL8, NE differentiation, miRNA32

Highlights

Targeting androgen–AR signals increase infiltrating mast cells.

Infiltrated mast cells increase NE differentiation via altering AR–mRNA32 signal.

Enzalutamide increases NE differentiation via increased infiltrating mast cells.

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common diagnosed cancer in men in the US (Siegel et al., 2013), and the androgen receptor (AR) signals play critical roles for PCa initiation and progression (Chang et al., 1988b; Heinlein and Chang, 2004). Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is the standard treatment for advanced PCa, which can suppress PCa progression during the first 12–24 months before development into the castration resistant PCa (CRPC) (Chang et al., 2014 Jun 19, 2008, 2010). Interestingly, early studies also linked the ADT‐induced CRPC to the PCa neuroendocrine (NE) differentiation without a clear mechanism (Abrahamsson, 1999).

Early studies indicated that several types of inflammatory immune cells in the prostate tumor microenvironment might influence PCa progression. Mast cells, one of these immune cells, were previously known by their function in allergies and anaphylaxis (Gounaris et al., 2007; Soucek et al., 2007), and recent evidences indicated mast cells might play important roles in fostering angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, and immuno‐modulation in various tumors (Gounaris et al., 2007; Soucek et al., 2007). Interestingly, conflicting results indicated that mast cells could either increase in the prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN) stage in the TRAMP mouse PCa, or have opposite roles in tumor progression and prognosis (Fleischmann et al., 2009).

There are two different types of mast cells in tumors, intra‐ and peri‐tumoral mast cells (Johansson et al., 2010). Intra‐tumoral mast cells may play a protective role in tumor development and are associated with good prognosis, yet the peri‐tumoral mast cells may promote tumor growth and are associated with a bad prognosis (Franck‐Lissbrant et al., 1998). The PCa recruited mast cells are generally located in the peri‐tumoral area, and can be increased in the prostate stromal area after castration (Zudaire et al., 2006). Whether these recruited mast cells can promote the PCa NE differentiation, however, remains unclear. Interestingly, results from in vitro cell culture and in vivo animal model studies revealed that ADT might induce PCa NE differentiation (Yuan et al., 2007), and androgen‐sensitive LNCaP cells exhibit the capability of being differentiated into an NE‐like phenotype in response to ADT (Shen et al., 1997).

Interleukin‐8 (IL‐8), also known as CXCL8, is a pro‐inflammatory CXC chemokine that can influence the migration of several cell types including the endothelial cells, macrophages and mast cells (Feuser et al., 2012; Inamura et al., 2002). However, the IL8 effects on the AR signals remain controversial (Araki et al., 2007; Seaton et al., 2008), even though most data agree that IL8 could promote tumor progression (Nilsson et al., 1999; Waugh and Wilson, 2008).

Recently, a new class of small RNAs, termed micro‐RNAs (miRNAs), were found to be able to influence the tumor progression via modulating both mRNA stability and translation ability into protein (Lim et al., 2005). Some of these miRNAs, including miRNA221 and miRNA663 were reported to be able to promote NE differentiation (Jiao et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2012).

Here we report how ADT with enzalutamide (also known as MDV3100) can influence the recruitment of mast cells and their impacts on the promotion of PCa NE differentiation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

RWPE1, LNCaP and CWR22Rv1 cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), and RWPE1 was grown in K‐SFM media (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), LNCaP and CWR22Rv1 were grown in RPMI (Invitrogen). C4‐2 and C4‐2B were gift from Dr. Jer‐Tsong Hsieh of UT Southwestern Medical Center and were grown in RPMI with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Human mast cell line HMC‐1 cells were a gift from Dr. John Frelinger of the Eye Institute of the University of Rochester Medical Center. HMC‐1 was cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS, 2 mM l‐glutamine, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. All cell lines have been tested following ATCC's instruction in the last 3 months.

2.2. Reagents and materials

GAPDH (6c5) and AR (N‐20) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Paso Robles, CA). Enolase‐2 (D20H2) (NSE) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling (Boston, MA). Tryptase antibody was purchased from DAKO (Dako Denmark, Glostrup Denmark). IL8 neutralizing antibody was purchased from R&D (Minneapolis, MN). Elisa kits were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). miRNA‐32 and miRNA‐let7a mimics and inhibitors were purchased from QIAGEN. Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent was purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY), Casodex was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Canada). Enzalutamide/MDV3100 for in vitro study was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX).

2.3. Mast cells recruitment assay

Mast cell migration was detected using a 24‐well transwell assay. Briefly, prostate cells conditioned media (CM) were placed in the lower chamber of a 24‐well transwell plate. Mast cells (1 × 105 cells/mL) were then seeded in the upper chamber. The upper and lower chambers were separated by an 8 μm polycarbonate filter coated with fibronectin (10 μg/ml, sc‐29011 Santa Cruz) and dried for 1 h in the hood. The chambers were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C, the cells removed from the upper chamber, filters were then washed, fixed with cold methanol, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Cell migration was measured by counting the number of cells attached to the lower surface of the filter. Each type of CM was tested in triplicate. The results were expressed as the mean of the number of migrating cells.

2.4. RNA extraction, miRNA extraction, and reverse transcription and quantitative real‐time PCR analysis

For RNA extraction, total RNAs were isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). 1 μg of total RNA was subjected to reverse transcription using Superscript III transcriptase (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). miRNAs were isolated using PureLink® miRNA kit. In brief, 50 ng small RNAs were processed for poly A addition by adding 1 unit of polymerase with 1 mM ATP in 1×RT buffer at 37 °C for 10 min in 10 μl volume, then heat inactivated at 95 °C for 2 min, add 50 pM anchor primer to 12.5 μl, and incubated at 65 °C for 5 min. Then for the last step of cDNA synthesis, we added 2 μl 5× RT buffer, 2 μl 10 mM dNTP, 1 μl reverse transcriptase to total 20 μl, and incubated at 42 °C for 1 h (Luo et al., 2012). Quantitative real‐time PCR was conducted using a Bio‐Rad CFX96 system with SYBR green to determine the mRNA expression level of a gene of interest. Expression levels of total RNAs were normalized to the expression of GAPDH RNA. Expression levels of miRNAs were normalized to the expression of U6 RNA.

2.5. MicroRNA (miRNA) transfection

miRNA transfection was performed as follows. Briefly, 33 nM miRNA in 250 μl Opti‐MEM® were transfected into PCa cells by Lipofectamine® 2000 system (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). 5 μl of Lipofectamine was diluted in 250 μl Opti‐MEM® media, mixed gently, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The diluted miRNA was then gently mixed with the diluted Lipofectamine® 2000, and incubated for 20 min at room temperature prior to being applied to transfect PCa cells.

2.6. Western Blot analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer 50 mM Tris/pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCI, 1% TritonX‐100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and sodium orthovanadate, sodium fluoride, EDTA and proteins (20 μg) were separated on 10–12% SDS/PAGE gel and then transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). After blocking membranes with 5% milk for 1 h at room temperature they were incubated with appropriate dilutions of specific primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. The blots were incubated with HRP‐conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h and visualized using ECL system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY).

2.7. In vivo animal model

Male 6‐ to 8‐week old nude mice were used. 10 mice were injected with CWR22Rv1 cells (1 × 106 cells, as a mixture with Matrigel, 1:1) and 10 mice were co‐injected with CWR22Rv1 and HMC‐1 (10:1) cells into the anterior prostates (AP). Every week we monitored tumor growth and measured tumor sizes, and mice were sacrificed at the end of 6 weeks. All animal studies were performed under the supervision and guidelines of the University of Rochester Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.8. Enzalutamide treated animal model

Male 6‐ to 8‐week old nude mice were used. 20 mice were injected with C4‐2 cells (C4‐2 cells are sensitive to enzalutamide treatment, but CWR22Rv1 cells are not) (1 × 106 cells, as a mixture with Matrigel, 1:1) and 20 mice were co‐injected with C4‐2 and HMC‐1 (10:1) cells into APs. After tumors formed (about 2–3 weeks), half the mice in each group were treated with enzalutamide (10 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection or DMSO for control every two days for 4 weeks, and then mice sacrificed and tissues collected for IHC staining. All animal studies were performed under the supervision and guidelines of the University of Rochester Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.9. Histology and IHC staining

Mouse prostate tissues were fixed in 10% (v/v) formaldehyde in PBS, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5 μm sections. Prostate sections were deparaffinized in xylene solution and rehydrated using gradient ethanol concentrations, and immunostaining was performed.

2.10. Statistics

All statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). The data values were presented as the mean ± SD. Differences in mean values between two groups were analyzed by two‐tailed Student's t test. p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

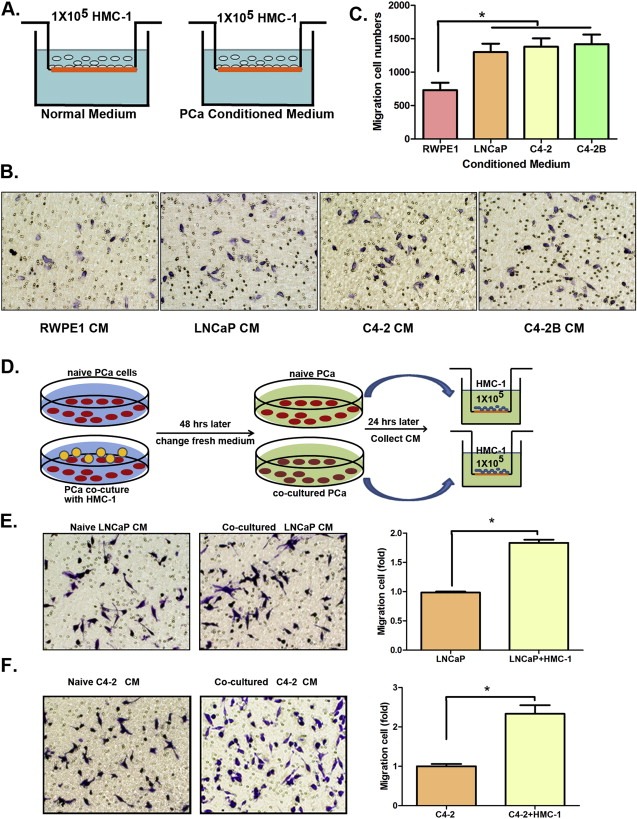

3.1. PCa cells recruit more mast cells than normal prostate epithelial cells

Early studies suggested that mast cells could be recruited to various tumors, including PCa (Johansson et al., 2010). Here we applied the Boyden chamber migration system (Figure 1A) to assay the mast HMC‐1 cells migration ability using PCa cells vs non‐malignant prostate epithelial RWPE1 cells. We first cultured LNCaP cells or RWPE1 cells individually for 24 h, then transferred each of their cultured CM to the lower Boyden chambers with the fresh HMC‐1 cells on the upper chambers, and then assayed for mast cell migration ability. The results showed LNCaP cells CM had a better capacity to recruit mast cells than RWPE1 cells CM (Figure 1B–C, p < 0.05). Similar results were also obtained when we used CM from other PCa cells including C4‐2 and C4‐2B cells (Figure 1B–C).

Figure 1.

PCa cells CM recruit more mast cells than normal prostate cells CM. A. Cartoon illustration of the mast cells recruitment assay. B. PCa cells promote mast cell migration. Mast cells (1 × 105) were added in the upper well, we placed non‐malignant prostate RWPE1 cell CM and 3 different PCa (LNCaP, C4‐2, and C4‐2B) cells CMs to do migration assay. C. Quantitation data for migrated mast cells. D. Cartoon shows PCa cells co‐culture system and how to collect CM to measure mast cell recruitment. E. The pictures show migrated mast cells stained with 0.1% crystal violet (microscope power is 200×), and the Quantification (at right) for mast cells migration recruited by naive LNCaP and co‐cultured LNCaP CMs. F. The pictures show migrated mast cells stained with 0.1% crystal violet (200×), and the Quantification (at right) for mast cells migration recruited by naive C4‐2 and co‐cultured C4‐2 CMs. Results were presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were done by two‐tailed Student's t test, *p < 0.05.

Together, results from Figure 1A–C suggest that the CM from PCa cells could recruit more mast cells than the CM from normal prostate epithelial cells.

We also cultured LNCaP cells alone vs co‐cultured with recruited HMC‐1 cells first and replaced fresh media for another 24 h. We then collected the CM and transferred to the Boyden chamber with fresh HMC‐1 cells on the top to determine their migration ability (Figure 1D). The results revealed that CM from co‐cultured LNCaP cells had better capacity than CM from LNCaP cells alone or HMC‐1 cells alone to recruit mast cells (Figure 1E and Figure S1A). Similar results were also obtained when we replaced LNCaP cells with C4‐2 cells (Figure 1F and Figure S1B).

Together, results from Figure 1A–F and Figure S1 conclude that the CM from PCa cells have better capacity than CM from normal prostate cells to recruit mast cells.

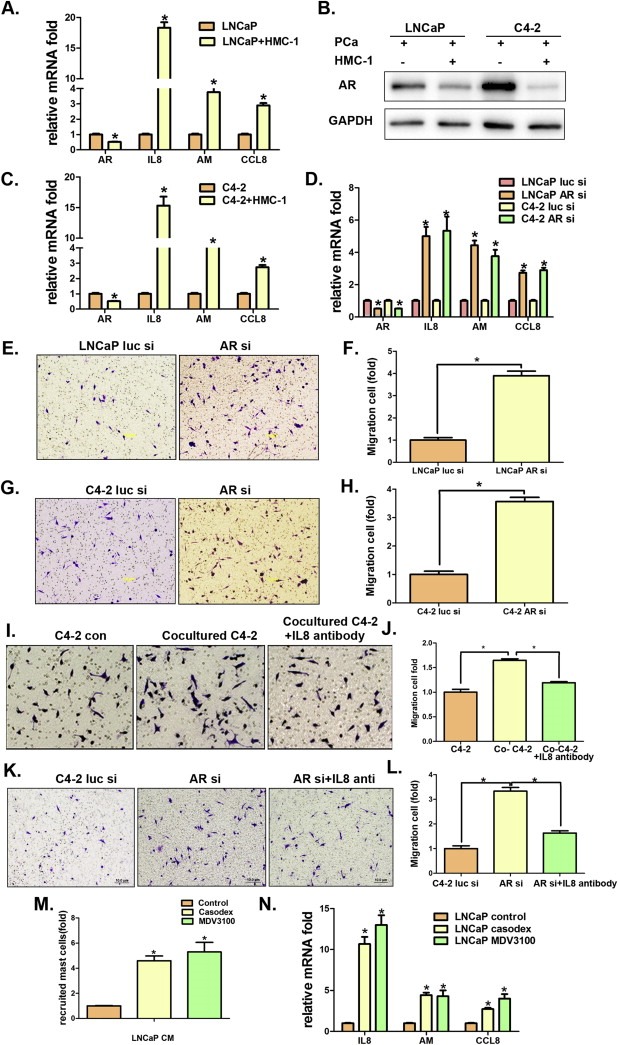

3.2. Mechanism dissection why PCa cells can recruit more mast cells

Using focus array we found the expression of several chemo‐attractants (Halova et al., 2012), including IL8, Adrenomedullin (AM) and CCL8, in LNCaP cells were enhanced after co‐culture with the HMC‐1 cells (Figure 2A). Interestingly, we also found the expression of AR, the key player to promote PCa progression (Chang et al., 1988, 2002, 2013, 2013), was suppressed (mRNA level in Figure 2A and protein level in Figure 2B) in LNCaP cells after co‐culture with HMC‐1 cells. Similar results were also obtained when we replaced LNCaP cells with C4‐2 cells (Figure 2C and Figure S2A–B).

Figure 2.

Mechanism(s) why co‐cultured PCa cells can recruit more mast cells. A. Q‐PCR shows mast cell chemo‐attractants, IL8, Adrenomedullin (AM), and CCL8 expression and AR expression in LNCaP cells (co‐cultured with or without mast cells). B. Western Blot to confirm AR expression in PCa cells after co‐culture with mast cells. C. Expression of mast cells chemo‐attractants, IL8, AM, and CCL8, and AR assayed by Q‐PCR in C4‐2 cells. D. Q‐PCR shows mast cells chemo‐attractants, IL8, AM, and CCL8, expression upon knocking down AR by siRNA in LNCaP and C4‐2 cells. E. The effects of LNCaP cells (with or without AR knockdown by siAR) CM on recruiting mast cells. F. Quantification for HMC‐1 migrated cells by CM of LNCaP siLuc or LNCaP siAR. G. The effects of C4‐2 cells (with or without AR knockdown by siAR) CM on recruiting mast cells. H. Quantification for HMC‐1 migrated cells by CM of C4‐2 siLuc or C4‐2 siAR. I. IL8 neutralizing antibody inhibits mast cells migration using transwell assay with C4‐2 and HMC‐1 co‐cultured CM in the bottom well. J. Quantification of mast cell migration in Figure I. K. IL8 neutralizing antibody to block mast cells migration toward CM of C4‐2 cells with AR knockdown. L. Quantification of mast cells migration in Figure K. M. LNCaP cells were maintained in RPMI with 10% CD serum and 1 nM DHT, treated with 10 μM casodex and 10 μM enzalutamide (MDV3100), DMSO as control. After 48 h, collect CM and process mast cells recruitment assays. Shown is the quantification data for mast cells migration. N. Expression of IL8, AM and CCL8 in LNCaP cells with different treatments. Statistical analyses were done by two‐tailed Student's t test. *p < 0.05.

These results suggest that recruited mast cells may function through suppression of AR to promote the mast cell chemo‐attractants (Halova et al., 2012) expression, which may then allow PCa cells to recruit more mast cells.

To prove the above conclusion, we first demonstrated that addition of AR‐siRNA (Figure S3) to suppress PCa AR in LNCaP (or C4‐2) cells enhanced the expression of the chemo‐attractants including IL8, AM and CCL8 (Figure 2D and Figure S2C–D), and increased the recruitment of HMC‐1 cells (Figure 2E–F). Similar results were also obtained when we replaced LNCaP cells with C4‐2 cells (Figure 2G–H).

We then applied another approach via IL8 interruption showing that addition of IL8 neutralizing antibody into C4‐2 cells partially reversed the C4‐2 cell ability to recruit the HMC‐1 cells (Figure 2I–J). Similarly, addition of IL8 neutralizing antibody into C4‐2 cells also could partially reverse the AR‐siRNA ability to recruit the HMC‐1 cells (Figure 2K–L).

Importantly, we replaced the AR‐siRNA with anti‐androgen casodex or enzalutamide to mimic the clinical condition, which occurs in PCa patients receiving ADT treatment. The results revealed that addition of anti‐androgen enzalutamide (or casodex) had an effect similar to the AR‐siRNA that could enhance the recruitment of mast cells in vitro (Figure 2M and Figure S2E) and in vivo (Figure S4) with increased expression of IL8 and AM expression (Figure 2N and Figure S2F).

Together, results from Figure 2A–N suggest that co‐culturing PCa cells with mast cells may lead to modulation of the AR → IL8 signals to further enhance the recruitment of mast cells, and suppression of androgen/AR signals with either enzalutamide/MDV3100 (or casodex) or AR‐siRNA enhances the recruitment of mast cells to PCa.

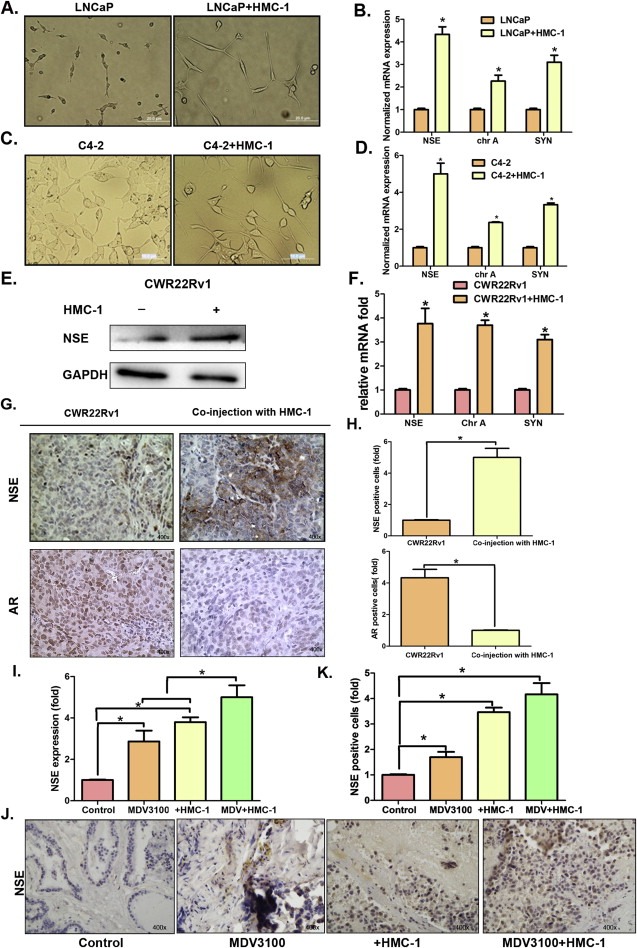

3.3. Mast cells promote neuroendocrine (NE) differentiation

While examining the consequences of PCa recruitment of mast cells, we noticed a very interesting phenotype of the PCa cells after being co‐cultured with mast HMC‐1 cells. As shown in Figure 3A and C and Figure S5A, PCa (LNCaP and C4‐2) cells morphology changed from spindle‐shaped cells to much longer cells with a longer cellular antennae that looks very similar to NE cells (Qiu et al., 1998). Importantly, we found this morphology change is in line with increased expression of NE cell markers including neuron‐specific enolase (NSE), chromogranin A (chr A) and synaptophysin (SYN) (Figure 3B and D, Figure S5B). Similar results were also obtained when we replaced C4‐2 with CWR22Rv1 cells (Figure 3E, F).

Figure 3.

Mast cells promote neuroendocrine differentiation in vitro and in vivo. A. LNCaP cells morphology change when co‐cultured with or without HMC‐1 cells (×200). B. Q‐PCR detection of Neuron‐specific enolase (NSE), chromogranin A (chr A) and synaptophysin (SYN) NE markers in LNCaP cells with or without HMC‐1 co‐culture. C. C4‐2 cells morphology change when co‐cultured with or without HMC‐1 cells (×200). D. Q‐PCR detection of NE markers expression in C4‐2 cells with or without HMC‐1 cells co‐culture. E. The expression of NE marker NSE in CWR22Rv1 cells with or without HMC‐1 co‐culture. F. QPCR detection of NE markers in CWR22Rv1 cells with or without HMC‐1 cells. G. IHC staining of NSE expression in xenograft PCa tissues. H. Quantitation of IHC staining of NSE for Figure 3G. I. QPCR detection of (Figure 3 Continued) NSE expression in C4‐2 cells with different treatment, 10 μM enzalutamide (MDV3100), co‐culture with HMC‐1 cells, and combining 10 μM MDV3100 and HMC‐1 cells. J. IHC staining of NSE expression in different C4‐2 orthotopic xenograft tumors, C4‐2 cells alone, C4‐2 tumor treated with MDV3100, co‐injection of C4‐2 with HMC‐1 (10:1) cells, and co‐injection group with MDV3100 treatment. K. Quantitation of IHC staining of NSE for Figure 3J. Results were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were done by two‐tailed Student's t test. *p < 0.05.

We also confirmed the above in vitro results with an in vivo mouse model. As shown in Figure 3G–H, staining NE cells with NSE antibody in mice with orthotopically xenografted CWR22Rv1 cells alone vs co‐injected with mast cells (10:1) revealed that the co‐injected mast cells enhanced the NE cells proportion in PCa and decreased the AR expression. As expected, enzalutamide promoted NE differentiation was also demonstrated with similar effects in mice (Figure 3I–K).

Together, results from Figure 3A–K suggest that the recruited mast cells promote NE differentiation in PCa and adding enzalutamide also induces NE differentiation in PCa cells.

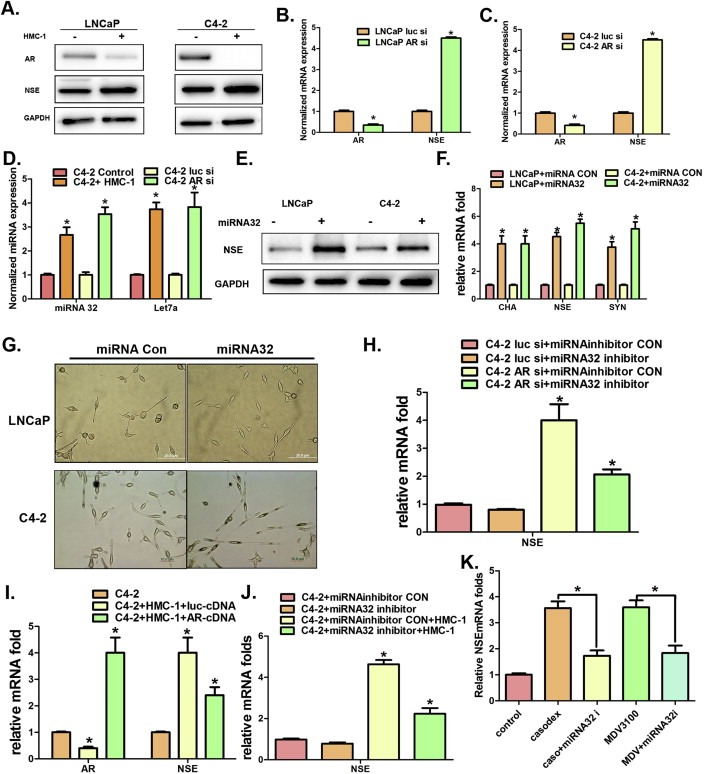

3.4. Mechanism(s) why recruited mast cells can promote NE differentiation in PCa

As Figure 2A–C showed recruited mast cells could suppress AR expression in PCa cells, and early studies also suggested that targeting androgens/AR could promote NE differentiation (Wright et al., 2003), we were interested in testing if recruited mast cells could also function through suppression of AR to enhance NE differentiation in PCa cells. We first demonstrated that co‐culturing LNCaP cells with HMC‐1 cells suppressed AR and increased NSE (Figure 4A). Similar results were also obtained in C4‐2 cells (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Mechanism(s) why mast cells can promote NE differentiation in PCa. A. Western Blot shows HMC‐1 co‐cultured with PCa (LNCaP and C4‐2) cells could decrease AR expression, but increase NSE expression in PCa cells. B. Q‐PCR shows knocking down AR in LNCaP cells increases NSE expression. C. Q‐PCR shows knocking down AR in C4‐2 cells increases NSE expression. D. Q‐PCR shows increased miRNA32 and miRNA‐let7a expression in C4‐2 cells when co‐cultured with HMC‐1 cells. E and F. Increased NSE expression at protein and RNA levels in LNCaP and C4‐2 cells following the transfection of mimic miRNA32. G. Morphology changes of LNCaP and C4‐2 cells following the transfection of mimic miRNA32. H. Q‐PCR detection of NSE expression in C4‐2 cells with or without transfection of miRNA32 inhibitor. I. Q‐PCR detection of AR and NSE expression in C4‐2 cells with or without co‐culture with HMC‐1 cells. J. Detection of NSE mRNA expression after the transfection of miRNA32 inhibitor in C4‐2 cells with or without AR knockdown. K. Detection of NSE mRNA expression after C4‐2 cells was treated with 10 μM casodex or 10 μM enzalutamide (MDV3100, MDV) with or without transfection of miRNA32 inhibitor. *p < 0.05.

We then confirmed that targeting AR (with AR‐siRNA) also decreased AR expression and increased NSE expression in LNCaP cells (Figure 4B) and C4‐2 cells (Figure 4C). As expected, we obtained similar results when we replaced the AR‐siRNA with enzalutamide (or casodex) to target androgen/AR signaling with enhanced NE differentiation in PCa cells (Figure S6A–C), suggesting that recruited mast cells may function through suppression of androgen/AR signals to enhance NE differentiation in PCa cells.

We then asked if AR might function through modulation of miRNAs to enhance NE differentiation as early studies suggested that miRNAs could also promote NE differentiation (Lee et al., 2012). After screening several AR‐related miRNAs, we found targeting AR with AR‐siRNA increased the expression of miRNA32 and miRNA‐let7a (Figure 4D). Importantly, we found co‐culturing C4‐2 cells with HMC‐1 cells also enhanced the expression of miRNA32 and miRNAlet7a (Figure 4D). However, we found miRNA32, but not miRNA‐let7a (data not shown), could increase NSE (Figure 4E–F) and promote NE differentiation (Figure 4G), and adding miRNA32 inhibitor suppressed AR‐siRNA‐enhanced NSE (Figure 4H).

We then applied the interruption approach to verify recruited mast cells might function through AR‐miRNA32 signals to enhance PCa NE differentiation. We added functional AR in the co‐culture of PCa cells with mast cells and found AR‐cDNA could increase AR expression and decrease recruited mast cells‐enhanced PCa NSE (Figure 4I). Similarly, adding miRNA32 inhibitor also suppressed recruited mast cells‐enhanced NSE (Figure 4J). Importantly, we found that adding miRNA32 inhibitor also reversed the enzalutamide (or casodex)‐induced NSE (Figure 4K).

Together, results from Figure 4A–K suggest that recruited mast cells can function through suppression of AR → miRNA32 signals to promote the NE differentiation in PCa cells.

4. Discussion

In normal non‐tumor cells, mast cells may be recruited to play roles related to allergic processes (Prussin and Metcalfe, 2003). However, with the development of tumors, the mast cells may be recruited more easily to the area because of various chemo‐attractants secreted by the tumors (Halova et al., 2012). Among more than 30 identified chemo‐attractants, many were also detected in PCa (Johansson et al., 2010). Other studies also suggested that mast cells could be viewed as the novel independent prognostic markers that might be linked to the PCa progression (Taverna et al., 2013).

Our finding showing recruited mast cells help to promote the NE differentiation in PCa may further expand the roles of mast cells‐NE differentiation in PCa progression. This may have important clinical implications because it may represent the first evidence showing ADT with anti‐androgen enzalutamide (or casodex) may function through the promotion of mast cell recruitment to enhance the PCa NE differentiation. Since the increase of the NE differentiation has been linked to the PCa progression, our finding here may provide new targets to suppress the NE differentiation via interrupting the infiltration of mast cells from the prostate tumor microenvironment.

Early studies suggested that while the NE cells can be detected in most PCa tumors, yet the number of NE cells may vary from case to case with an average of no more than 1% of all tumor cells, (even though a few cases did have abundant NE cells) (Li et al., 2013). Importantly, other studies also suggested that the NE cells in tumors might promote PCa progression into the castration resistant stage (Deeble et al., 2007) with the alteration of the metastasis (Uchida et al., 2006) via their secreted products (DaSilva et al., 2013; Tawadros et al., 2013). Therefore, our finding showing recruited mast cells that is enhanced by either enzalutamide or (casodex) help to promote the NE differentiation in PCa, may further expand the roles of infiltrated mast cells‐NE differentiation in PCa progression and may raise the concern of potential unwanted side effects of these powerful anti‐androgens.

The mechanisms why targeting androgen/AR signals leads to increase the NE differentiation in PCa remain unclear. Li et al. found IL8‐CXCR5‐P53 signal is involved in the NE differentiation (Li et al., 2013), and Park et al. found P21 may function through PAK4 to promote NE differentiation (Park et al., 2012). Our finding of the potential involvement of miRNAs (Zheng et al., 2012), especially the miRNA‐32 and miRNA‐let7a, suggest that targeting this newly identified AR‐miRNA32 signal may allow us to develop a better therapy to suppress the NE differentiation‐induced PCa cell invasion.

Other reports also suggested that PCa NE differentiation could be enhanced by some secreted cytokines. For example, Liu Q et al. found IL‐1β could promote PCa to acquire NE cell‐like features (Liu et al., 2013). Alonzeau J et al. found 26RFa might participate in the development of PCa via promoting the PCa NE differentiation (Alonzeau et al., 2013), and IL‐6, EGF or Wnt‐11 could induce NE‐like differentiation in LNCaP cells (Qiu et al., 2012, 1998).

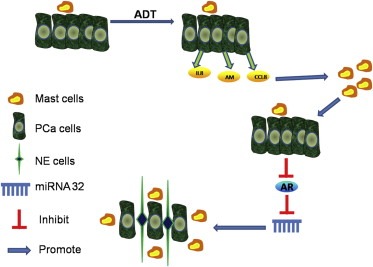

In summary, our results conclude that infiltrated mast cells could decrease PCa AR expression and promote NE differentiation. The decrease of AR not only can increase mast cell chemo‐attractants secretion, which will enhance PCa capacity to recruit mast cells, but also inhibit miRNA32 to promote NE differentiation. This may provide us a better understanding of the importance of mast cells in the prostate tumor microenvironment (Figure 5). The finding of ADT with enzalutamide (or casodex) enhanced mast cell recruitment may further help us to develop potential new therapies via combining the current ADT with a novel therapy to target the newly identified AR → IL8 and/or AR → miRNA32 signals to simultaneously suppress PCa growth as well as NE differentiation.

Figure 5.

Cartoon summary of study. PCa cells can recruit mast cells, but the recruitment will be increased after ADT treatment and targeting AR, that is because PCa cells secretes more chemo‐attractants like IL8, AM and CCL8. When mast cells are recruited to the PCa, cells they would suppress AR signaling, and self‐feedback to recruit more mast cells and this also suppresses AR that will induce PCa cells NE differentiation via miRNA32.

5. Conclusions

We conclude that enzalutamide (or casodex) and infiltrating mast cells could enhance the PCa cells capacity to recruit more mast cells, which might then lead to enhance the PCa NE differentiation via modulation of the miRNA32 signals. Targeting these newly identified signals from infiltrated mast cells → AR → miRNA32 may help us to suppress the CRPC progression.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Supporting information

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Fig. S1 Co‐cultured PCa cell have better capacity to recruit mast cell. We repeated mast cell migration assay and added HMC‐1 conditioned medium as control, A. LNCaP conditioned media compare with HMC‐1, and quantification. B. C4‐2 cell conditioned media compare with HMC‐1, and quantification. *p < 0.05.

Fig. S2 Prepare the standard dilution on the microwell plate and add 100 μl of Assay Buffer (1×) in duplicate to all standard wells. Pipette 100 μl of prepared standard in duplicate into wells. Add 80 μl of Assay Buffer (1×) and 20 μl of each sample in duplicate to the sample wells. Add 50 μl of HRP‐Conjugate to all wells and incubate at room temperature (18–25 °C) for 2 h. Pipette 100 μl of TMB Substrate Solution to all wells. Alternatively the colour development can be monitored by the ELISA reader at 620 nm. The substrate reaction should be stopped as soon as Standard 1 has reached an OD of 0.9–0.95.A. IL8 protein levels in C4‐2 cells and mast cells co‐cultured with C4‐2 cells were tested by ELISA assay. B. Adrenomedullin (AM) protein levels in C4‐2 cells and mast cells co‐cultured with C4‐2 cells were tested by ELISA assay. C. IL8 protein levels in C4‐2 luc si and C4‐2 AR si cells. D. AM protein levels in C4‐2 luc si and C4‐2 AR si cells. E. Mast cells recruitment. Collect different CM from C4‐2 cell treated with DMSO (control), 10 μM casodex and 10 μM MDV3100 for 2 days, and then perform mast cells recruitment assay for 4 h. F. Q‐PCR shows mast cells chemo‐attractants (IL8, Adrenomedullin, and CCL8) expression in C4‐2 cells after treated with different drugs. *p < 0.05.

Fig. S3 AR knock down efficiency in LNCaP and C4‐2 cells. Lentivirus package and transfection: Design the AR siRNA sequences and inserted into the PLKO1.0 vector, and packaged with psPAX2 and pMD2.G plasmid. Then transfected into 293T cell for 48hr to get the lentivirus soup. Collected the lentivirus soup and frozen in −80 °C for use. The pSuperior–ARsiRNA targeting human AR mRNA sequence is 5′‐gtggccgccagcaaggggctg‐3′ (1530–1550); and then use the lentivirus soup to infection LNCaP and C4‐2 cells for 48 h, and then WB to detect AR protein expression.

Fig. S4 MDV3100 can enhance mast cells recruitment in vivo. We used PCa orthotopic xenograft mice model to determine the effect of MDV3100 on mast cells recruitment. Male 6‐ to 8‐week old nude mice were used. 40 mice were injected with C4‐2 cells (C4‐2 cells are sensitive to MDV3100 treatment, but CWR22Rv1 cells are not) (1 × 106 cells, as a mixture with Matrigel, 1:1) into anterior prostate (AP). After tumors formed (about 2–3 weeks), 20 mice were treated with MDV3100 (10 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection or DMSO for control every two days for 4 weeks, on the first day of 7th week, half of the mice in each group were injected HMC‐1 cells in tail vein, and 1 week later sacrificed mice and collected tissue for IHC. A. Mast cells staining, using anti‐human tryptase to mark the mast cells HMC‐1 in tumor. B. Quantification data for positive cells after IHC staining. *p < 0.05.

Fig. S5 Mast cells promote neuroendocrine differentiation. We changed the system by using 0.4 μm transwell to process the co‐culture, which can avoid HMC‐1 cell to adhere on PCa cell. A.C4‐2 cell morphology change after co‐culture with HMC‐1. B. QPCR show NE markers (NSE, chromogranin A and SYN) expression after co‐culture. *p < 0.05.

Fig. S6 MDV3100 and casodex can induce NE differentiation. A. C4‐2 cells morphology changes after treatment with DMSO (control), 10 μM casodex and 10 μM MDV3100. B. Q‐PCR shows NE marker NSE expression after treated with different drugs. C. NSE protein expression after treated with different drugs. *p < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant CA156700 and George Whipple Professorship Endowment, and Taiwan Department of Health Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence grant DOH99‐TD‐B‐111‐004. China National Program on Key Basic Research Project (973 Program NO. 2012CB518305).

Supplementary data 1.

1.1.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2015.02.010.

Dang Qiang, Li Lei, Xie Hongjun, He Dalin, Chen Jiaqi, Song Wenbing, Chang Luke S., Chang Hong-Chiang, Yeh Shuyuan, Chang Chawnshang, (2015), Anti-androgen enzalutamide enhances prostate cancer neuroendocrine (NE) differentiation via altering the infiltrated mast cells → androgen receptor (AR) → miRNA32 signals, Molecular Oncology, 9, doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.02.010.

Contributor Information

Lei Li, Email: lilydr@163.com.

Chawnshang Chang, Email: chang@urmc.rochester.edu.

References

- Abrahamsson, P.A. , 1999. Neuroendocrine differentiation in prostatic carcinoma. The Prostate 39, 135–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonzeau, J. , Alexandre, D. , Jeandel, L. , Courel, M. , Hautot, C. , Yamani, F.-Z.E. , Gobet, F. , Leprince, J. , Magoul, R. , Amarti, A. , 2013 Jan. The neuropeptide 26RFa is expressed in human prostate cancer and stimulates the neuroendocrine differentiation and the migration of androgeno-independent prostate cancer cells. Eur. J. Cancer 49, (2) 511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki, S. , Omori, Y. , Lyn, D. , Singh, R.K. , Meinbach, D.M. , Sandman, Y. , Lokeshwar, V.B. , Lokeshwar, B.L. , 2007. Interleukin-8 is a molecular determinant of androgen independence and progression in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 67, 6854–6862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C. , Kokontis, J. , Liao, S. , 1988. Structural analysis of complementary DNA and amino acid sequences of human and rat androgen receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85, 7211–7215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C. , Lee, S.O. , Yeh, S. , Chang, T.M. , 2014 Jun 19. Androgen receptor (AR) differential roles in hormone-related tumors including prostate, bladder, kidney, lung, breast and liver. Oncogene 33, (25) 3225–3234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.S. , Kokontis, J. , Liao, S.T. , 1988. Molecular cloning of human and rat complementary DNA encoding androgen receptors. Science 240, 324–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, M.A. , Cariaga-Martinez, A.E. , Lobo, M.V. , Orozco, R.M.M. , Motiño, O. , Rodríguez-Ubreva, F.J. , Angulo, J. , López-Ruiz, P. , Colás, B. , 2012. EGF promotes neuroendocrine-like differentiation of prostate cancer cells in the presence of LY294002 through increased ErbB2 expression independent of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT pathway. Carcinogenesis 33, 1169–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DaSilva, J.O. , Amorino, G.P. , Casarez, E.V. , Pemberton, B. , Parsons, S.J. , 2013 Jun. Neuroendocrine-derived peptides promote prostate cancer cell survival through activation of IGF-1R signaling. Prostate 73, (8) 801–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeble, P.D. , Cox, M.E. , Frierson, H.F. , Sikes, R.A. , Palmer, J.B. , Davidson, R.J. , Casarez, E.V. , Amorino, G.P. , Parsons, S.J. , 2007. Androgen-independent growth and tumorigenesis of prostate cancer cells are enhanced by the presence of PKA-differentiated neuroendocrine cells. Cancer Res. 67, 3663–3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuser, K. , Thon, K.P. , Bischoff, S.C. , Lorentz, A. , 2012. Human intestinal mast cells are a potent source of multiple chemokines. Cytokine 58, 178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann, A. , Schlomm, T. , Kollermann, J. , Sekulic, N. , Huland, H. , Mirlacher, M. , Sauter, G. , Simon, R. , Erbersdobler, A. , 2009. Immunological microenvironment in prostate cancer: high mast cell densities are associated with favorable tumor characteristics and good prognosis. Prostate 69, 976–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck-Lissbrant, I. , Haggstrom, S. , Damber, J.E. , Bergh, A. , 1998. Testosterone stimulates angiogenesis and vascular regrowth in the ventral prostate in castrated adult rats. Endocrinology 139, 451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gounaris, E. , Erdman, S.E. , Restaino, C. , Gurish, M.F. , Friend, D.S. , Gounari, F. , Lee, D.M. , Zhang, G. , Glickman, J.N. , Shin, K. , Rao, V.P. , Poutahidis, T. , Weissleder, R. , McNagny, K.M. , Khazaie, K. , 2007. Mast cells are an essential hematopoietic component for polyp development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 19977–19982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halova, I. , Draberova, L. , Draber, P. , 2012. Mast cell chemotaxis – chemoattractants and signaling pathways. Front. Immunol. 3, 119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinlein, C.A. , Chang, C. , 2002. Androgen receptor (AR) coregulators: an overview. Endocr. Rev. 23, 175–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinlein, C.A. , Chang, C. , 2004. Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr. Rev. 25, 276–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamura, H. , Kurosawa, M. , Okano, A. , Kayaba, H. , Majima, M. , 2002. Expression of the interleukin-8 receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 on cord-blood-derived cultured human mast cells. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 128, 142–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, L. , Deng, Z. , Xu, C. , Yu, Y. , Li, Y. , Yang, C. , Chen, J. , Liu, Z. , Huang, G. , Li, L.C. , 2014 Jul. MicroRNA-663 induces castration-resistant prostate cancer transformation and predicts clinical recurrence. J. Cell Physiol. 229, (7) 834–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, A. , Rudolfsson, S. , Hammarsten, P. , Halin, S. , Pietras, K. , Jones, J. , Stattin, P. , Egevad, L. , Granfors, T. , Wikstrom, P. , Bergh, A. , 2010. Mast cells are novel independent prognostic markers in prostate cancer and represent a target for therapy. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 1031–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.W. , Lee, E.H. , Ha, S.Y. , Lee, C.H. , Chang, H.K. , Chang, S. , Kwon, K.Y. , Hwang, I.S. , Roh, M.S. , Seo, J.W. , 2012. Altered expression of microRNA miR-21, miR-155, and let-7a and their roles in pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Pathol. Int. 62, 583–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Chen, C.J. , Wang, J.K. , Hsia, E. , Li, W. , Squires, J. , Sun, Y. , Huang, J. , 2013 May. Neuroendocrine differentiation of prostate cancer. Asian J. Androl. 15, (3) 328–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, L.P. , Lau, N.C. , Garrett-Engele, P. , Grimson, A. , Schelter, J.M. , Castle, J. , Bartel, D.P. , Linsley, P.S. , Johnson, J.M. , 2005. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature 433, 769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T. , Izumi, K. , Lee, S. , Lin, W. , Yeh, S. , Chang, C. , 2013. Anti-androgen receptor ASC-J9 versus anti-androgens MDV3100 (enzalutamide) or casodex (bicalutamide) leads to opposite effects on prostate cancer metastasis via differential modulation of macrophage infiltration and STAT3–CCL2 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 4, e764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.H. , Lee, S.O. , Niu, Y. , Xu, D. , Liang, L. , Li, L. , Yeh, S.D. , Fujimoto, N. , Yeh, S. , Chang, C. , 2013. Differential androgen deprivation therapies with anti-androgens casodex/bicalutamide or MDV3100/Enzalutamide versus anti-androgen receptor ASC-J9(R) Lead to promotion versus suppression of prostate cancer metastasis. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 19359–19369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q. , Russell, M.R. , Shahriari, K. , Jernigan, D.L. , Lioni, M.I. , Garcia, F.U. , Fatatis, A. , 2013. Interleukin-1β promotes skeletal colonization and progression of metastatic prostate cancer cells with neuroendocrine features. Cancer Res. 73, 3297–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X. , Zhang, J. , Wang, H. , Du, Y. , Yang, L. , Zheng, F. , Ma, D. , 2012. PolyA RT-PCR-based quantification of microRNA by using universal TaqMan probe. Biotechnol. Lett. 34, 627–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, G. , Mikovits, J.A. , Metcalfe, D.D. , Taub, D.D. , 1999. Mast cell migratory response to interleukin-8 is mediated through interaction with chemokine receptor CXCR2/Interleukin-8RB. Blood 93, 2791–2797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y. , Altuwaijri, S. , Yeh, S. , Lai, K.P. , Yu, S. , Chuang, K.H. , Huang, S.P. , Lardy, H. , Chang, C. , 2008. Targeting the stromal androgen receptor in primary prostate tumors at earlier stages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 12188–12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y. , Chang, T.M. , Yeh, S. , Ma, W.L. , Wang, Y.Z. , Chang, C. , 2010. Differential androgen receptor signals in different cells explain why androgen-deprivation therapy of prostate cancer fails. Oncogene 29, 3593–3604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, M. , Lee, H. , Lee, C. , You, S. , Kim, D. , Park, B. , Kang, M. , Heo, W. , Shin, E. , Schwartz, M. , 2012. p21-Activated kinase 4 promotes prostate cancer progression through CREB. Oncogene 32, 2475–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prussin, C. , Metcalfe, D.D. , 2003. 4. IgE, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 111, S486–S494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y. , Robinson, D. , Pretlow, T.G. , Kung, H.-J. , 1998. Etk/Bmx, a tyrosine kinase with a pleckstrin-homology domain, is an effector of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase and is involved in interleukin 6-induced neuroendocrine differentiation of prostate cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95, 3644–3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, A. , Scullin, P. , Maxwell, P.J. , Wilson, C. , Pettigrew, J. , Gallagher, R. , O'Sullivan, J.M. , Johnston, P.G. , Waugh, D.J. , 2008. Interleukin-8 signaling promotes androgen-independent proliferation of prostate cancer cells via induction of androgen receptor expression and activation. Carcinogenesis 29, 1148–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, R. , Dorai, T. , Szaboles, M. , Katz, A.E. , Olsson, C.A. , Buttyan, R. , 1997. Transdifferentiation of Cultured Human Prostate cancer Cells to a Neuroendocrine Cell Phenotype in a Hormone-depleted Medium, Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations Elsevier; 67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, R. , Naishadham, D. , Jemal, A. , 2013. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J. Clin 63, 11–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucek, L. , Lawlor, E.R. , Soto, D. , Shchors, K. , Swigart, L.B. , Evan, G.I. , 2007. Mast cells are required for angiogenesis and macroscopic expansion of Myc-induced pancreatic islet tumors. Nat. Med. 13, 1211–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverna, G. , Giusti, G. , Seveso, M. , Hurle, R. , Colombo, P. , Stifter, S. , Grizzi, F. , 2013. Mast cells as a potential prognostic marker in prostate cancer. Dis. Markers 35, 711–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawadros, T. , Alonso, F. , Jichlinski, P. , Clarke, N. , Calandra, T. , Haefliger, J.-A. , Roger, T. , 2013. Release of macrophage migration inhibitory factor by neuroendocrine-differentiated LNCaP cells sustains the proliferation and survival of prostate cancer cells. Endocrine-Related Cancer 20, 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida, K. , Masumori, N. , Takahashi, A. , Itoh, N. , Kato, K. , Matusik, R.J. , Tsukamoto, T. , 2006. Murine androgen-independent neuroendocrine carcinoma promotes metastasis of human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. The Prostate 66, 536–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, D.J. , Wilson, C. , 2008. The interleukin-8 pathway in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 6735–6741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, M.E. , Tsai, M.J. , Aebersold, R. , 2003. Androgen receptor represses the neuroendocrine transdifferentiation process in prostate cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 1726–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, T.C. , Veeramani, S. , Lin, M.F. , 2007. Neuroendocrine-like prostate cancer cells: neuroendocrine transdifferentiation of prostate adenocarcinoma cells. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 14, 531–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C. , Yinghao, S. , Li, J. , 2012. MiR-221 expression affects invasion potential of human prostate carcinoma cell lines by targeting DVL2. Med. Oncol. 29, 815–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zudaire, E. , Martinez, A. , Garayoa, M. , Pio, R. , Kaur, G. , Woolhiser, M.R. , Metcalfe, D.D. , Hook, W.A. , Siraganian, R.P. , Guise, T.A. , Chirgwin, J.M. , Cuttitta, F. , 2006. Adrenomedullin is a cross-talk molecule that regulates tumor and mast cell function during human carcinogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 168, 280–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Fig. S1 Co‐cultured PCa cell have better capacity to recruit mast cell. We repeated mast cell migration assay and added HMC‐1 conditioned medium as control, A. LNCaP conditioned media compare with HMC‐1, and quantification. B. C4‐2 cell conditioned media compare with HMC‐1, and quantification. *p < 0.05.

Fig. S2 Prepare the standard dilution on the microwell plate and add 100 μl of Assay Buffer (1×) in duplicate to all standard wells. Pipette 100 μl of prepared standard in duplicate into wells. Add 80 μl of Assay Buffer (1×) and 20 μl of each sample in duplicate to the sample wells. Add 50 μl of HRP‐Conjugate to all wells and incubate at room temperature (18–25 °C) for 2 h. Pipette 100 μl of TMB Substrate Solution to all wells. Alternatively the colour development can be monitored by the ELISA reader at 620 nm. The substrate reaction should be stopped as soon as Standard 1 has reached an OD of 0.9–0.95.A. IL8 protein levels in C4‐2 cells and mast cells co‐cultured with C4‐2 cells were tested by ELISA assay. B. Adrenomedullin (AM) protein levels in C4‐2 cells and mast cells co‐cultured with C4‐2 cells were tested by ELISA assay. C. IL8 protein levels in C4‐2 luc si and C4‐2 AR si cells. D. AM protein levels in C4‐2 luc si and C4‐2 AR si cells. E. Mast cells recruitment. Collect different CM from C4‐2 cell treated with DMSO (control), 10 μM casodex and 10 μM MDV3100 for 2 days, and then perform mast cells recruitment assay for 4 h. F. Q‐PCR shows mast cells chemo‐attractants (IL8, Adrenomedullin, and CCL8) expression in C4‐2 cells after treated with different drugs. *p < 0.05.

Fig. S3 AR knock down efficiency in LNCaP and C4‐2 cells. Lentivirus package and transfection: Design the AR siRNA sequences and inserted into the PLKO1.0 vector, and packaged with psPAX2 and pMD2.G plasmid. Then transfected into 293T cell for 48hr to get the lentivirus soup. Collected the lentivirus soup and frozen in −80 °C for use. The pSuperior–ARsiRNA targeting human AR mRNA sequence is 5′‐gtggccgccagcaaggggctg‐3′ (1530–1550); and then use the lentivirus soup to infection LNCaP and C4‐2 cells for 48 h, and then WB to detect AR protein expression.

Fig. S4 MDV3100 can enhance mast cells recruitment in vivo. We used PCa orthotopic xenograft mice model to determine the effect of MDV3100 on mast cells recruitment. Male 6‐ to 8‐week old nude mice were used. 40 mice were injected with C4‐2 cells (C4‐2 cells are sensitive to MDV3100 treatment, but CWR22Rv1 cells are not) (1 × 106 cells, as a mixture with Matrigel, 1:1) into anterior prostate (AP). After tumors formed (about 2–3 weeks), 20 mice were treated with MDV3100 (10 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection or DMSO for control every two days for 4 weeks, on the first day of 7th week, half of the mice in each group were injected HMC‐1 cells in tail vein, and 1 week later sacrificed mice and collected tissue for IHC. A. Mast cells staining, using anti‐human tryptase to mark the mast cells HMC‐1 in tumor. B. Quantification data for positive cells after IHC staining. *p < 0.05.

Fig. S5 Mast cells promote neuroendocrine differentiation. We changed the system by using 0.4 μm transwell to process the co‐culture, which can avoid HMC‐1 cell to adhere on PCa cell. A.C4‐2 cell morphology change after co‐culture with HMC‐1. B. QPCR show NE markers (NSE, chromogranin A and SYN) expression after co‐culture. *p < 0.05.

Fig. S6 MDV3100 and casodex can induce NE differentiation. A. C4‐2 cells morphology changes after treatment with DMSO (control), 10 μM casodex and 10 μM MDV3100. B. Q‐PCR shows NE marker NSE expression after treated with different drugs. C. NSE protein expression after treated with different drugs. *p < 0.05.