Abstract

A mild, asymmetric Heck–Matsuda reaction of five-, six- and seven-membered ring alkenes and aryldiazonium salts is presented. High yields and enantioselectivities were achieved using Pd(0) and chiral anion co-catalysts, the latter functioning as a chiral anion phase-transfer (CAPT) reagent. For certain substrate classes, the chiral anion catalysts were modulated to minimize the formation of undesired by-products. More specifically, BINAM-derived phosphoric acid catalysts were shown to prevent alkene isomerization in cyclopentene and cycloheptene starting materials. DFT(B3LYP-D3) computations revealed that increased product selectivity resulted from a chiral anion dependent lowering of the activation barrier for the desired pathway.

Keywords: Heck, Matsuda, Heck reaction, Chiral Anion Phase-Transfer Catalysis, Palladium, BINAM-derived phosphoric acid

Graphical abstract

An asymmetric Heck-Matsuda reaction of cyclopentene, cyclohexene, and cycloheptene derivatives has been developed using a Chiral Anion Phase Transfer (CAPT) Catalysis. These studies demonstrate that CAPT catalysis can be employed to control the enantio- and chemoselectivity of the Heck-Matsuda

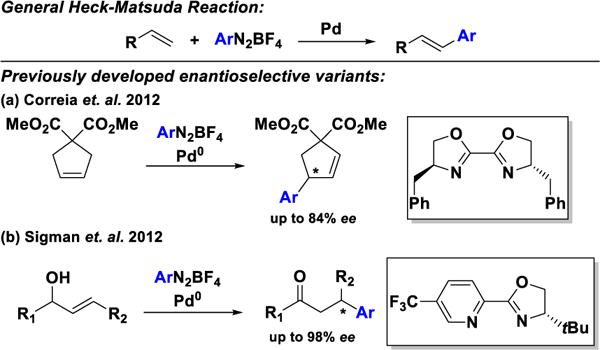

The Heck–Matsuda arylation reaction[1] (Scheme 1) offers notable advantages over traditional cross-coupling chemistry.[2] Aryl diazonium salts, easily prepared from the corresponding anilines,[3] are much more reactive than their aryl halide and sulfonate counterparts.[4] Thus, reactions can typically be performed under milder conditions.[2b,5] Additionally, oxidation-sensitive ligands are not required, avoiding the need for rigorous exclusion of oxygen.[5] However, enantioselective variants of the Heck–Matsuda reaction are rare, largely because commonly employed chiral phosphine ligands are incompatible with diazonium salts.[6]

Scheme 1.

Heck–Matsuda reaction and enantioselective variants.

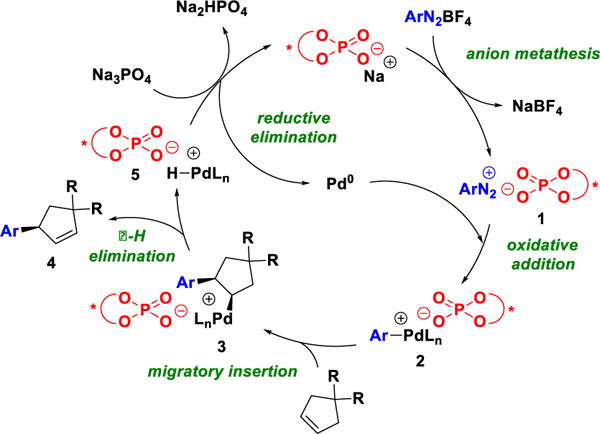

The groups of Correia[7] and Sigman[8] have addressed this challenge through the use of chiral bisoxazoline and pyridine oxazoline ligands, respectively. Correia and co-workers have developed arylative desymmetrizations of both cyclic and acyclic olefins (Scheme 1a), while the Sigman group has reported highly enantio and regioselective arylations of acyclic alkenyl alcohols of various chain lengths using a redox-relay strategy (Scheme 1b).[9] As an alternative approach, we envisioned the use of chiral anion phase transfer catalysis (CAPT) (Scheme 2).[10–12] In this strategy, an insoluble diazonium salt is transported into organic solution via anion exchange with a lipophilic phosphate salt to produce ion-pair 1.[11a,12] After oxidative addition by a Pd(0) species and loss of N2, the chiral phosphate remains as a counterion to the resulting cationic Pd(II) intermediate [2,11b] Migratory insertion of the olefin then provides intermediate 3. This step is rendered enantioselective by virtue of the associated chiral anion.[11a] β-hydride elimination and olefin disassociation affords desired product 4 and Pd-hydride 5. We envisioned 5 undergoing formal reductive elimination via two plausible pathways, either by deprotonation by the phosphate counterion (shown in Scheme 2) or by the inorganic base present in the mixture. Both pathways regenerate Pd(0) and chiral phosphate co-catalysts.

Scheme 2.

Enantioselective Heck–Matsuda reaction via chiral anion phase t ransfer catalysis.

Notably, the outlined mechanism posits that the chiral anion is associated with the cationic palladium catalyst throughout the catalytic cycle. This hypothesis implies that the anion might be leveraged to mediate reactivity and selectivity arising from any or all of the elementary steps in the catalytic cycle. More specifically, alkene isomerization position by a palladium hydride intermediate (5), which has been previously noted as an issue of the Heck-Matsuda reaction of unactivated cyclic alkenes,[4b,13] might be subject to anion control. However, while the number of examples of chiral phosphate anion-controlled enantioselectivity is rapidly increasing, the use of these anions to influence reaction outcomes beyond enantioselectivity remains rare.[14] Herein, we demonstrate that CAPT catalysis can be employed to control the enantio- and chemoselectivity of the Heck-Matsuda reaction.

To test the viability of the hypothesis outlined above, cyclopentene 6 was treated with 5 mol% Pd2dba3, 1.4 equivalents of phenyldiazoniumtetrafluoroborate, 6 equivalents of Na2CO3, and 10 mol% 7a as a phase-transfer catalyst in toluene. Under these conditions the desired product was formed in good yield and with a significant level of enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 1). After examining various non-polar solvents, catalysts, inorganic bases, and reaction temperatures, the optimal results were obtained using a 3:2 mixture of benzene and MTBE as solvent, K2CO3 as the inorganic base, and H8-TCYP (7a) as the chiral anion at 10 °C (Table 1, entry 8). Notably, the reaction did not proceed in the absence of a phase-transfer catalyst (Table 1, entry 5) and was slowed in the absence of base, while, affording product in diminished enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 6). These results are consistent with the proposed phase-transfer mechanism.

Table 1.

Reaction Optimization[a]

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | CAPT | solvent | base | temp | yield (%)[b] | ee (%)[c] |

| 1 | 7a | toluene | Na2CO3 | r.t. | 76 | 49 |

| 2 | 7a | benzene | Na2CO3 | r.t. | 80 | 57 |

| 3 | 7a | MTBE | Na2CO3 | r.t. | 68 | 59 |

| 4 | 7a | benzene/MTBE 3:2 | Na2CO3 | r.t. | 86 | 68 |

| 5 | – | benzene/MTBE 3:2 | Na2CO3 | r.t. | 9 | – |

| 6 | 7a | benzene/MTBE 3:2 | – | r.t. | 40 | 7 |

| 7 | 7a | benzene/MTBE 3:2 | K2CO3 | r.t. | 97 | 70 |

| 8 | 7a | benzene/MTBE 3:2 | K2CO3 | 10 °C | 80 | 85 |

| 9 | 7b | benzene/MTBE 3:2 | Na2CO3 | r.t. | 85 | 45 |

| 10 | 7c | benzene/MTBE 3:2 | Na2CO3 | r.t. | 61 | 63 |

| 11 | 7d | benzene/MTBE 3:2 | Na2CO3 | r.t. | 94 | 40 |

| 12 | 7e | benzene/MTBE 3:2 | Na2CO3 | r.t. | 88 | 43 |

| 13 | 7f | benzene/MTBE 3:2 | Na2CO3 | r.t. | 82 | 36 |

| ||||||

Conditions: 6 (1 equiv, 0.027 mmol); phenyldiazonium tetrafluoroborate (1.4 equiv); Pd2(dba)3 (0.05 equiv); 7 (0.1 equiv); base (6 equiv); solvent (0.75 mL); 24 h.

Yield determined by 1H-NMR utilizing 1,4-dinitrobenzene as an internal standard.

Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral HPLC. MTBE: Methyl tert-butyl ether.

With an optimized set of conditions in hand, the scope of the aryl diazonium salt was examined (Table 2). Generally, substitution at the meta- and para- positions of this reagent was well-tolerated, affording products in good yields and enantioselectivities. Specifically, strongly electron-donating groups (Table 2, 8d–e), and electron-withdrawing groups (Table 2, 8b–c) were viable under the optimized reaction conditions. Disubstitution of the aryl diazonium salt was also well-tolerated (Table 2, 8f and 8i). In contrast, while high enantioselectivity was obtained with an ortho-substituted diazonium, the yield was diminished (Table 2, 8j). Notably, enantioselectivities using various aryl diazonium salts under CAPT catalysis compare favorably with those previously reported for this class of substrate.[7a]

Table 2.

Aryl Diazonium Scope[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R = | yield (%)[b] | ee (%)[c] |

| 1 | H (8a) | 82 | 85 |

| 2 | 3-CF3 (8b) | 70 | 84 |

| 3 | 4-F (8c) | 81 | 85 |

| 4 | 3-OMe (8d) | 81 | 79 |

| 5 | 4-OMe (8e) | 73 | 82 |

| 6 | 3,5-Me (8f) | 79 | 82 |

| 7 | 4-fBu (8g) | 82 | 87 |

| 8 | 4-Ph (8h) | 66 | 85 |

| 9 | 4-OMe, 3-CI (8i) | 80 | 80 |

| 10 | 2-F (8j) | 15 | 94 |

Conditions: 6 (1 equiv, 0.054mmol); aryldiazonium tetrafluoroborate (1.4 equiv); Pd2(dba)3 (0.05 equiv); 7a (0.10 equiv); K2CO3 (2 equiv); solvent (1.6 mL); 24 h.

Isolated yields.

Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral phase HPLC.

Given the results for disubstituted cyclopentene derivatives, we sought to expand the scope to mono-substituted analogues, with the aim of achieving high diastereo- and enantioselectivity. When cyclopentene 9 was subjected to the phase-transfer Heck–Matsuda conditions, the desired product was obtained as a single diastereomer in moderate enantioselectivity. Slight modification of reaction conditions, namely altering the inorganic base to Cs2CO3, improved the enantioselectivities up to 90% ee (Table 3). Substitution of the aryl diazonium salt with an electronically diverse set of substituents was well tolerated.

Table 3.

Arylation of Monosubstituted Cyclopentene[a]

|

Conditions: 9 (1 equiv, 0.05mmol); aryldiazonium tetrafluoroborate (1.5 equiv); Pd2(4-MeO-dba)3 (0.05 equiv); 7a (0.10 equiv); Cs2CO3 (2 equiv); toluene (1.0 mL); 24 h.

Isolated yields.

Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral HPLC.

Examination of additional cyclopentene derivatives revealed divergent reactivity using spirocyclic substrates. For instance, reaction of olefin 11, using BINOL-derived phosphoric acid as a catalyst 7a, produced a 3:2 mixture of the desired product 12 and isomerized starting material 13 (Table 4, entry 1).

Table 4.

Catalyst Control of Olefin Isomerization[a]

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | CAPT | solvent | base | 12 : 13 | conv. (%)[b] | ee (%)[c] |

| 1 | 7a | toluene | Na2CO3 | 3 : 2 | 50 | 40 |

| 2 | 7g | toluene | Na2CO3 | >20:1 | 78 | 55 |

| 3 | 7g | toluene | Na2HPO4 | >20:1 | 95 | 57 |

| 4 | 7h | toluene | Na2HPO4 | >20:1 | 75 | 36 |

| 5 | 7i | toluene | Na2HPO4 | >20:1 | 96 | 74 |

| 6 | 7j | tol/MTBE 1:1 | Na2HPO4 | >20:1 | 50 | 82 |

| 7 | 7k | tol/MTBE 1:1 | Na2HPO4 | >20:1 | 95 | 82 |

| 8 | 7k | MTBE | Na2HPO4 | >20:1 | 95 | 87 |

| ||||||

Conditions: 11 (1 equiv, 0.025mmol); 4-fluorophenyldiazonium tetrafluoroborate (1.2equiv); Pd2(dba)3 (0.05 equiv); 7 (0.1 equiv); base (2 equiv); solvent (0.50 mL); 24 h.

Conversion determined by crude 1HNMR.

Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral HPLC.

Low conversion.

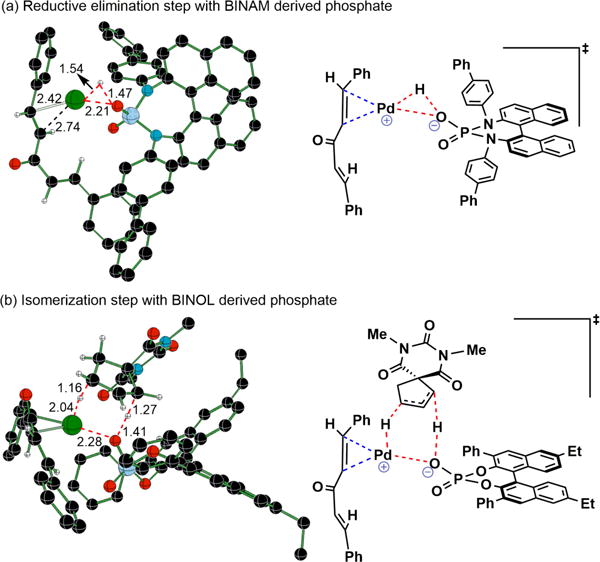

Alkene isomer 13 likely arises from coordination of Pd-hydride 5 (Figure 1) to 11 followed by migratory insertion and β-hydride elimination. To inhibit this undesired isomerization pathway, we hypothesized that a more basic counterion would increase the rate of reductive elimination, thus decreasing the lifetime of the cationic Pd-hydride. A variety of chiral phosphoric acids with a more electron rich binapthyl diamine (BINAM) backbone were prepared.[12b,15] When 11 was subjected to the same reaction conditions, but with BINAM-derived phosphoric acids (BDPA, 7g-k) as the catalyst, the desired product was generated without isomerization of starting material (Table 4, entries 2–8).

Figure 1.

Optimized transition state geometries for (a) reductive elimination and (b) isomerization of 11 in the presence of chiral phosphates at the SMD(Toluene)/B3LYP-D3/6-31G**, LANL2DZ(Pd) level of theory. The distances are in Å. Only selected hydrogen atoms are shown for improved clarity. C=black, O=red, H=gray, N=cyan, P=blue and Pd=green.

Furthermore, examination of BDPA catalysts with different N-aryl substituents and re-optimization of reaction conditions, allowed for the selective formation of the desired Heck-Matsuda adduct in good yield and high enantioselectivity (Table 4, entry 8). Various aryl diazonium salts were viable coupling partners using these conditions with enantioselectivities up to 92% (Table 5).[16]

Table 5.

Aryl Diazonium Scope[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R = | yield (%) [b] | ee (%)[c] |

| 1 | H (12a) | 70 | 86 |

| 2 | 4-tBu (12b) | 92 | 92 |

| 3 | 4-Me (12c) | 67 | 90 |

| 4 | 4-F (12d) | 79 | 85 |

| 5 | 3-F (12e) | 92 | 84 |

| 6 | 3-CF3 (12f) | 94 | 90 |

Conditions: 11 (1 equiv, 0.025mmol); aryldiazonium tetrafluoroborate (1.5 equiv); Pd2(dba)3 (0.05 equiv); 7k (0.10 equiv); Na2HPO4 (2 equiv); solvent (0.50 mL); 24 h.

Isolated yields.

Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral phase HPLC.

Having established BDPAs as catalysts for the CAPT Heck-Matsuda reaction, we turned our attention to larger ring systems that had previous given low selectivity with either traditional ligands [7a] or BINOL-derived catalysts. To this end, tetrahydrophthalimide derivative 14 was subjected to CAPT conditions. The reaction of 14, using 7a as the catalyst, provided the Heck adduct in low enantioselectivity. Examination of BINAM-phosphate 7n, using 4-fluorobenzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate as a coupling partner, afforded the Heck adduct in 84% ee and 40% yield. Due to presence of minor olefin isomers in the product,[17] the double bond was hydrogenated for analytical purposes without erosion of enantioselectivity (For further details See Supporting Information). Various aryl diazonium salts were viable coupling partners using these conditions with enantioselectivities up to 90% (Table 6).

Table 6.

Arylation of Cyclohexene Derivatives[a]

|

Conditions: 14 (1 equiv, 0.041mmol); aryldiazonium tetrafluoroborate (1.4 equiv); Pd2(dba)3 (0.05 equiv); 7n (0.10 equiv); Na2HPO4 (2 equiv); solvent (1.0 mL); 24 h.

Isolated yields for two steps.

Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral phase HPLC.

15a′ was isolated in the first step in 84% ee and 40% yield (See SI).

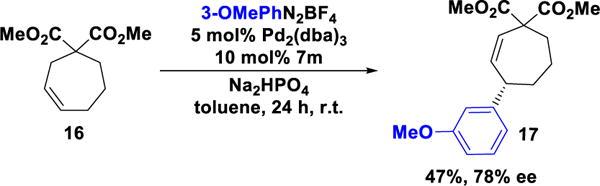

Given the results for six-membered ring derivatives we looked to expand the scope to seven-membered analogue 16. As had been previously observed with cyclopentenes, the reaction of olefin 16, using 7a as a catalyst, afforded the Heck adduct in 2.2:1 mixture of regioisomers and low enantioselectivity. In contrast, the reaction catalyzed by BDPA 7m afforded the desired product with high regioselectivity and 78% ee (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Arylation of Cycloheptene 16.

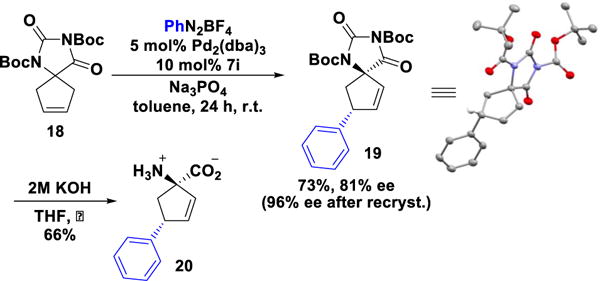

As an application of the developed method, hydantoin derivative 18, an amino acid precursor, was arylated under chiral anion phase transfer conditions. The Heck-Matsuda reaction of 18 catalyzed by BINOL-derived phosphoric acid 7a, generated 19 with 14% ee and 14:1 dr. In contrast, BDPA 7i catalyzed the desired transformation to afford 19 as a single diastereomer in good yield and 81% ee, which was upgraded to 96% ee by a single recrystallization (Scheme 4). The corresponding amino acid derivative 20 was readily generated by reaction of 19 under basic conditions. Conformationally constrained amino acids similar to 20 are known to be S1P1 receptor agonists[18a,7h], and have been previously prepared from optically active starting materials.[18b]

Scheme 4.

Enantioselective synthesis of amino acid 20.

The reductive elimination and isomerization steps[19] with both BINOL- and BINAM-derived phosphate counterions (Schemes 2 and S1) were investigated using density functional theory computations (B3LYP-D3).[20,21] The Gibbs free energies of activation computed at the SMD(Toluene)/B3LYP-D3/6-31G**, SDD(Pd)//SMD(Toluene)/B3LYP-D3/6-31G**,LANL2DZ(Pd) level of theory for reductive elimination step and isomerization of 11. The Gibbs free energy of activation for the reductive elimination (Figure 1a) was found to be 2.2 kcal/mol lower with a BINAM-phosphate than with a BINOL-phosphate (See Table S3, Supporting Information). Presumably, the presence of less inductively withdrawing and more π-donating N-aryl substituents results in a more basic phosphate and consequently, a more favorable reductive elimination.

Calculations indicate that the chiral phosphate works in concert with a cationic (dba)Pd-hydride[22] in the isomerization step. The optimized geometries (Figure 1b) indicate that the alkene accepts the hydride from the palladium while the phosphate oxygen simultaneously abstracts a methylene proton. When comparing BINOL- and BINAM-phosphates, isomerization barriers were found to be higher than the reductive elimination by 2.5 and 5.5 kcal/mol, respectively (See Table S3, Supporting Information). These values are in agreement with the experimental observations, as the alkene isomerization occurs when BINOL-phosphates are employed as co-catalysts, but is circumvented with the use of BINAM-phosphates.

In conclusion, we have developed an asymmetric Heck-Matsuda reaction of cyclopentene, cyclohexene, and cycloheptene derivatives using a chiral ion-pairing strategy. These first examples of chiral counterion controlled enantioselective Heck reactions offer an alternative to and compliment the recent advances in asymmetric variants employing chiral ligand. In addition, these comprise the first successful examples of enantioselective Heck-Matsuda arylation of a 6-membered ring system. In the cases of cyclopentene and cycloheptene starting materials, undesired alkene isomerization was circumvented by the application of BINAM-derived phosphoric acids as catalysts for CAPT. Furthermore, mechanistic insights gained through DFT calculations suggest that the nature of the counterion is integral to achieving the desired selectivity. More importantly, these results suggest that BINOL/BINAM-derived phosphate counterions, that have almost exclusively been employed to control enantioselectivity, may offer a more general means to control reactivity and selectivity in transition metal mediated processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35 GM118190 to F.D.T. and R01 GM063540 to M.S.S.) for partial support of this work and IITB super-computing for the computing time. C.M.A. thanks Science without Borders for a postdoctoral fellowship (CSF/CNPq 201758/2014-8) and H.M.N. acknowledges the UNCF and Merck for generous funding. Mr. S. Kim is acknowledged for the paper revision and helpful discussion and suggestions. Dr. G. Schäfer is acknowledged for helpful suggestions, and Dr. W. Wolf and A. G. DiPasquale for the X-ray structure of 15b and 19. X-ray crystallography was performed using the UC Berkeley College of Chemistry CheXray facility supported by the NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant S10- RR027172.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article can be found under.

References

- 1.Kikukawa K, Matsuda T. Chem Lett. 1977;6:159–162. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Roglans A, Pla-Quintana A, Moreno-Mañas M. Chem Rev. 2006;106:4622–4643. doi: 10.1021/cr0509861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Taylor JG, Moro AV, Correia CRD. Eur J Org Chem. 2011;2011:1403–1428. [Google Scholar]; c) Mo F, Dong G, Zhang Y, Wang J. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:1582–1593. doi: 10.1039/c3ob27366k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Felpin FX, Nassar-Hardy L, Le Callonnec F, Fouquet E. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:2815–2831. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balz G, Schiemann G. Ber dtsch Chem Ges A/B. 1927;60:1186–1190. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Andrus MB, Song C. Org Lett. 2001;3:3761–3764. doi: 10.1021/ol016724c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kikukawa K, Nagira K, Wada F, Matsuda T. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:31–36. [Google Scholar]; c) Sengupta S, Bhattacharya S. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1993:1943–1944. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Dai M, Liang B, Wang C, Chen J, Yang Z. Org Lett. 2004;6:221–224. doi: 10.1021/ol036182u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Masllorens J, Moreno-Mañas M, Pla-Quintana A, Roglans A. Org Lett. 2003;5:1559–1561. doi: 10.1021/ol034340b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Brunner H, de Courcy NLC, Genêt J-P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:4815–4818. [Google Scholar]; d) Masllorens J, Bouquillon S, Roglans A, Hénin F, Muzart J. J Organomet Chem. 2005;690:3822–3826. [Google Scholar]; e) Andrus MB, Song C, Zhang J. Org Lett. 2002;4:2079–2082. doi: 10.1021/ol025961s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Severino EA, Correia CRD. Org Lett. 2000;2:3039–3042. doi: 10.1021/ol005762d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Yasui S, Fujii M, Kawano C, Nishimura Y, Ohno A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:5601–5604. [Google Scholar]; b) Yasui S, Fujii M, Kawano C, Nishimura Y, Shioji K, Ohno A. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 2. 1994:177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Correia CRD, Oliveira CC, Salles AG, Jr, Santos EAF. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:3325–3328. [Google Scholar]; b) Oliveira CC, Angnes RA, Correia CRD. J Org Chem. 2013;78:4373–4385. doi: 10.1021/jo400378g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Angnes RA, Oliveira JM, Oliveira CC, Martins NC, Correia CRD. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:13117–13121. doi: 10.1002/chem.201404159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Carmona RC, Correia CRD. Adv Synth Catal. 2015;357:2639–2643. [Google Scholar]; e) Oliveira CC, Pfaltz A, Correia CRD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:14036–14039. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) deAzambuja F, Carmona RC, Chorro THD, Heerdt G, Correia CRD. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:11205–11209. doi: 10.1002/chem.201602572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) de Oliveira Silva J, Angnes RA, Menezes da Silva VH, Servilha BM, Adeel M, Braga AAC, Aponick A, Correia CRD. J Org Chem. 2016;81:2010–2018. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Khan IU, Kattela S, Hassan A, Correia CRD. Org Biomol Chem. 2016;14:9476–9480. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01892k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Kattela S, Heerdt G, Correia CRD. Adv Synth Catal. 2017;359:260–267. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner EW, Mei TS, Burckle AJ, Sigman MS. Science. 2012;338:1455–1458. doi: 10.1126/science.1229208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oestreich M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:2282–2285. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiral Counterion Strategy:; a) Hamilton GL, Kang EJ, Mba M, Toste FD. Science. 2007;317:496–499. doi: 10.1126/science.1145229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rauniyar V, Lackner AD, Hamilton GL, Toste FD. Science. 2011;334:1681–1684. doi: 10.1126/science.1213918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Mahlau M, List B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:518–533. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Phipps RJ, Hamilton GL, Toste FD. Nat Chem. 2012;4:603–614. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Brak K, Jacobsen EN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:534–561. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palladium-Organocatalysis:; a) Nelson HM, Williams BD, Miró J, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:3213–3216. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mukherjee S, List B. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11336–11337. doi: 10.1021/ja074678r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jiang G, Halder R, Fang Y, List B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:9752–9755. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Jiang G, List B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:9471–9474. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Chai Z, Rainey TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:3615–3618. doi: 10.1021/ja2102407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Banerjee D, Junge K, Beller M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:13049–13053. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Tao ZL, Zhang WQ, Chen DF, Adele A, Gong LZ. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9255–9258. doi: 10.1021/ja402740q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Jiang T, Bartholomeyzik T, Mazuela J, Willersinn J, Bäckvall J-E. Angew Chem. 2015;127:6122–6125. doi: 10.1002/anie.201501048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Nelson HM, Reisberg SH, Shunatona HP, Patel JS, Toste FD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:5600–5603. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nelson HM, Patel JS, Shunatona HP, Toste FD. Chem Sci. 2014;6:170–173. doi: 10.1039/c4sc02494j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yamamoto E, Hilton MJ, Orlandi M, Saini V, Toste FD, Sigman MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:15877–15880. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Kaganovsky L, Cho KB, Gelman D. Organometallics. 2008;27:5139–5145. [Google Scholar]; b) Peñafiel I, Pastor IM, Yus M. Eur J Org Chem. 2012;2012:3151–3156. [Google Scholar]; For a ligand-based approach to controlling alkene isomers in the Heck reactions see:; c) Hartung CG, Köhler K, Beller M. Org Lett. 1999;1:709–711. doi: 10.1021/ol9901063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Lauer MG, Thompson MK, Shaughnessy KH. J Org Chem. 2014;79:10837–10848. doi: 10.1021/jo501840u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.For reviews of ion-pairing in transition metal complexes see:; a) Macchioni A. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2039–2074. doi: 10.1021/cr0300439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Clot E. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2009;2009:2319–2328. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatano M, Ikeno T, Matsumura T, Torii S, Ishihara K. Adv Synth Catal. 2008;350:1776–1780. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The use of BDPA catalysts for the Heck-Matsuda reaction of 6 and 9 afforded the arylation products 8a and 13a in high yields as up to 65% and 52% ee, respectively (see supporting information, Table S1 and S2).

- 17.Unlike the reaction of with cyclopentene 11 and cycloheptene 16, alkeneisomers are the result of isomerization of the alkene in the product 15 into conjugation with the maleimide carbonyl group(s).

- 18.a) Zhu R, Snyder AH, Kharel Y, Schaffter L, Sun Q, Kennedy PC, Lynch KR, Macdonald TL. J Med Chem. 2007;50:6428–6435. doi: 10.1021/jm7010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wallace GA, Gordon TD, Hayes ME, Konopacki DB, Fix-Stenzel SR, Zhang X, Grongsaard P, Cusack KP, Schaffter LM, Henry RF, et al. J Org Chem. 2009;74:4886–4889. doi: 10.1021/jo900376b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Werner EW, Sigman MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13981–13983. doi: 10.1021/ja1060998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Werner EW, Sigman MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9692–9695. doi: 10.1021/ja203164p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jindal G, Sunoj RB. J Org Chem. 2014;79:7600–7606. doi: 10.1021/jo501322v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) All geometries were optimized at the SMD(Toluene)/B3LYP-D3/6-31G**,LANL2DZ(Pd) level of theory.Gaussian09, Rev. D.01 is employed for all the computations.; Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian09, Revision D.01. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford, CT: 2013. [Google Scholar]; (c) The optimized geometries of the transition states and intermediates for the reductive elimination and isomerization steps are respectively given in Figures S1 and S2 in the SI.

- 22.a) Sabino AA, Machado AHL, Correia CRD, Eberlin MN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:2514–2518. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Oliveira CC, dos Santos EAF, Nunes JHB, Correia CRD. J Org Chem. 2012;77:8182–8190. doi: 10.1021/jo3015209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.