SUMMARY

Computer models can be useful in planning interventions against novel strains of influenza. However such models sometimes make unsubstantiated assumptions about the relative infectivity of asymptomatic and symptomatic cases, or conversely assume there is no impact at all. Using household-level data from known-index studies of virologically confirmed influenza A infection, the relationship between an individual's infectiousness and their symptoms was quantified using a discrete-generation transmission model and Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. It was found that the presence of particular respiratory symptoms in an index case does not influence transmission probabilities, with the exception of child-to-child transmission where the donor has phlegm or a phlegmy cough.

Key words: Bayesian statistics, influenza A, modelling, symptoms, transmission

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of several novel strains of influenza and respiratory viruses over the past decade has challenged public health systems [1, 2]. Computational models can be useful tools when planning for epidemics, especially those caused by novel pathogens for which there is little evidence for the effectiveness of interventions. Examples where models’ predictions were subsequently validated empirically include the effectiveness of antiviral ring prophylaxis [3, 4] and the closure of schools during influenza pandemics to slow down the spread of infection [5, 6]. However, models are inherently limited by the accuracy of the data or assumptions used to construct them, and there are key unknowns that may impact the reliability of findings derived from modelling studies. For interventions against influenza pandemics, for instance, models need to make assumptions about the relative infectivity of asymptomatic or subclinical cases – these individuals are less likely to be detected by surveillance or to reduce their social contacts, and so may play an important role in propagating transmission. Many of the most influential models [7, 8] assume that asymptomatic cases are half as infectious as symptomatic ones, an assumption that dates back to Elveback et al.’s self-declared ‘guesstimate’ in the 1970s [9], but which does not appear to have been substantiated by evidence then or since.

This study quantifies the relationship between an individual's infectiousness and their symptoms, using household-level data in which index cases and their cohabitants had influenza A infection virologically confirmed and logged symptoms in a diary, and a discrete-generation transmission model combined with Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo methods.

METHODS

Data

Data were obtained from household influenza studies conducted in Hong Kong between February 2007 and June 2009. These were from a community-based randomized controlled trial that recruited individuals with influenza-like illness from outpatient clinics across Hong Kong, and their households. Detailed information on the study design can be found in Cowling et al. [10]. Briefly, index cases were recruited into the study if they (i) experienced the onset of at least two symptoms of acute respiratory illness (temperature ⩾37·8 °C, headache, myalgia or cough) within 48 h, (ii) lived in a household with at least two individuals, none of whom had a reported acute respiratory illness in the previous 14 days, and (iii) had a positive result using the QuickVue Influenza A + B rapid diagnostic test (Quidel, USA). At a later date, influenza was confirmed using either RT–PCR (during the 2008/2009 seasons) or viral culture (during 2007). The study involved three home visits over a period of 7–10 days. The first home visit occurred ideally within 36 h of recruitment, during which nasal and throat specimens were collected from all consenting household members. Recruited individuals and household members were then asked to keep a self-reported daily symptom diary for about 1 week. Subsequent home visits occurred 3 and 6 days after recruitment, to collect additional nasal and throat specimens from household members. All specimens were tested by RT–PCR (during the 2008/2009 seasons) or viral culture (during 2007).

All index cases with laboratory-confirmed influenza A (either RT–PCR or culture) were identified. For each of these individuals and their household members, we extracted from their symptom diaries the presence of the following respiratory symptoms: sore throat, cough, runny nose, phlegm, or the combination of cough and phlegm; missing values (~1·5% of symptoms) were treated as indicating symptom absence. Household members were considered to display evidence of infection if they had laboratory-confirmed influenza A during follow-up as the accuracy of these tests is high (~90% sensitivity, ~80% specificity [11]). Individuals were categorized as being adults if aged >18 years. The dataset used in the models has 462 influenza A cases (331 index cases, 131 secondary cases).

Model

We developed an age-structured chain binomial model [12] with transmission probabilities that varied by symptom presence. This model was separately fit to each symptom one at a time. This represents transmission as occurring in discrete infection generations, with those infected on generation g able to infect those as yet uninfected on generation g + 1 but not on subsequent generations. The transmission probability from individual i of age group ai ( = 0 if i is a child and 1 otherwise), where i has symptoms if si = 1 and not if 0, to individual j is . These eight risks were modelled as free parameters.

. These eight risks were modelled as free parameters.

Infection of those uninfected within the household at each generation is assumed to be independent, with risk from multiple sources compounding, i.e. if  is the set of infection in generation g, infection to

is the set of infection in generation g, infection to  is with probability

is with probability . Transmission ends when no new infections occur in any generation.

. Transmission ends when no new infections occur in any generation.

Four variants of the basic model were considered – no symptoms, half infectious, free parameter and multiple symptoms. The first ignored symptoms to obtain baseline transmission risks by age group of infective and household member. The second fixed the infectivity of asymptomatic cases at half that of symptomatic cases (as in Elveback et al. [9] and more recent papers). The free parameter model by contrast has an additional class of parameters that accounts for any respiratory symptoms present. The multiple symptoms model used the number ni of respiratory symptoms for each case i with infection risk , truncated to [0, 1] and the probability of infection varies with the number of symptoms.

, truncated to [0, 1] and the probability of infection varies with the number of symptoms.

For all models, the likelihood function could be evaluated directly if the generation of each infection were known. This happens only if the index fulfils case criteria, or if the index and one cohabitant do. For more infections, the order of infection must be explored, either by summing the probabilities of all infection generation combinations, or by data augmentation [13], i.e. treating the unobserved generation as an additional parameter to estimate (further details available in the Supplementary material). As there were households with four infections, we used the latter, as it was more computationally efficient than the former when the number of combinations was large.

Flat priors over [0, 1] for all proportions were taken (or on [ −10, 10] for the parameters of the multi-symptom model) and a Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithm was used to sample the resulting posterior. This used 10 chains each of 100 000 iterations with every 100th iteration retained and convergence assessed by visual inspection of trace plots. Posterior samples were converted to obtain equal tailed 95% credible intervals (CIs) for relevant estimands, and the distribution of risks with and without symptoms were compared by the posterior distribution of absolute difference in transmission risk. No adjustment for multiple estimation was attempted.

We screened for the model that fits the data best of the candidate models we considered using Deviance Information Criteria (DIC) described by Gelman et al. [14]. All analyses were performed in R statistical environment with a custom-designed script.

RESULTS

The risk of transmission from an infected child to a second child was 21·9% (95% CI 14·5–30·2), higher than the corresponding risk to a cohabiting adult [11·4%, 95% CI 9·1–14·2; relative risk (RR) 1·9, 95% CI 1·2–2·8]. Adults were less likely than children to transmit infection to other adults (6·9%, 95% CI 4·4–10·1; RR 0·6, 95% CI 0·3–0·96) or to children (10·0%, 95% CI 4·5–18·0; RR 0·5, 95% CI 0·2–1·0).

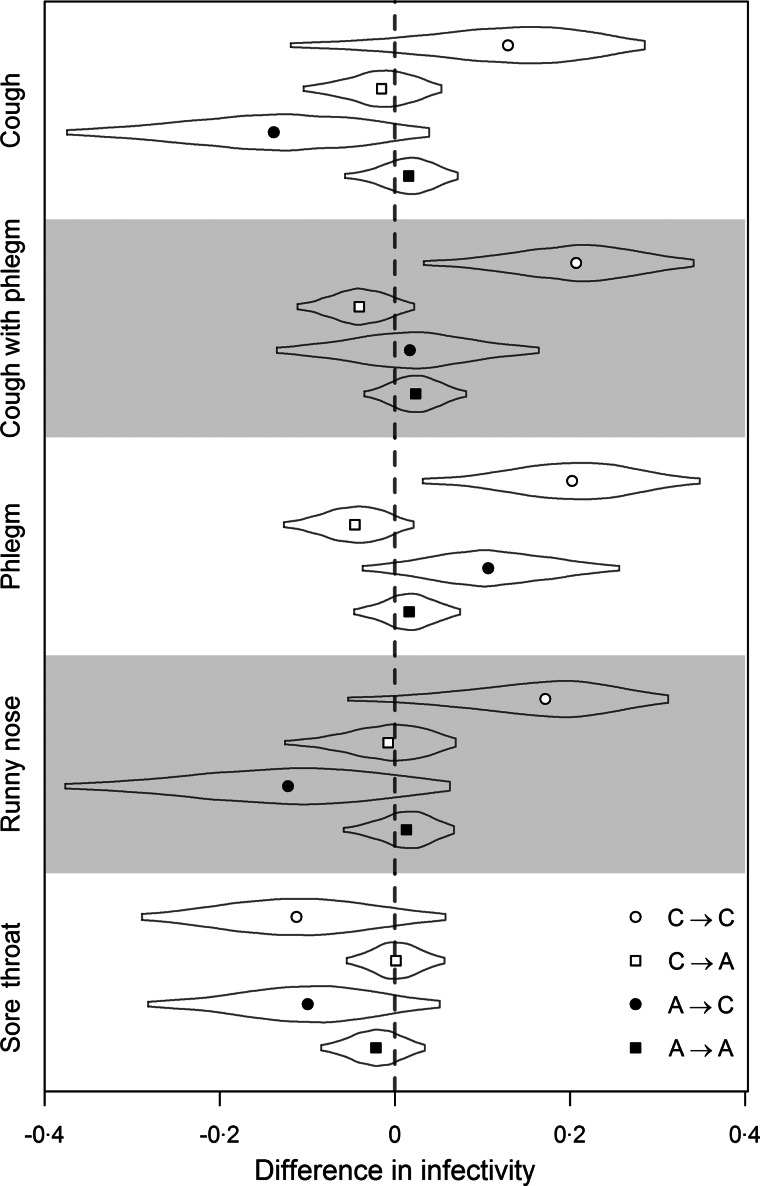

Estimated transmission risks from either adults or children to adults were not strongly affected by any of the respiratory symptoms assessed (Fig. 1, Table 1), which may have modulated transmission potential by at most 8·4 percentage points (from adults) or 13 percentage points (from children). There was much less certainty in the effect of adult symptoms on transmission potential to children (Fig. 1). In contrast, there was clear evidence that the presence of phlegm or a phlegmy cough in children was associated with an increased risk of infection in other children in the household [20 percentage points (95% CI 3·1–35) for phlegm, 21 percentage points (95% CI 3·2–34) for phlegm and cough]. The effect of cough and runny nose was in the same direction, although the sample sizes did not permit confirmation. The presence of a sore throat in infected children did not notably increase transmission risk to other children.

Fig. 1.

The effects of respiratory symptoms on the transmission risks from either adults or children to adults or children. Points are posterior medians, curves are posterior distributions truncated to within 95% credible intervals. Differences are in probability of infection between combinations of ages. C, Children; A, adults.

Table 1.

Estimated transmission risks from either adults or children to adults or children with or without symptoms

| Symptoms | Risk without symptoms | Risk with symptoms | Absolute risk difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path‡ | Median | 95% CI† | Median | 95% CI† | Median | 95% CI† | |

| Cough | C⟶C | 0·12 | (0·0095–0·36) | 0·25 | (0·16–0·36) | 0·13 | (−0·12 to 0·29) |

| C⟶A | 0·12 | (0·061–0·21) | 0·11 | (0·08–0·14) | −0·015 | (−0·1 to 0·054) | |

| A⟶C | 0·23 | (0·07–0·47) | 0·091 | (0·034–0·19) | −0·14 | (−0·38 to 0·041) | |

| A⟶A | 0·06 | (0·019–0·13) | 0·076 | (0·045–0·12) | 0·016 | (−0·057 to 0·072) | |

| Cough with phlegm | C⟶C | 0·071 | (0·006–0·23) | 0·28 | (0·19–0·4) | 0·21 | (0·032 to 0·34) |

| C⟶A | 0·14 | (0·087–0·2) | 0·1 | (0·071–0·13) | −0·041 | (−0·11 to 0·022) | |

| A⟶C | 0·12 | (0·037–0·24) | 0·13 | (0·045–0·27) | 0·017 | (−0·14 to 0·17) | |

| A⟶A | 0·058 | (0·025–0·11) | 0·083 | (0·046–0·13) | 0·024 | (−0·035 to 0·082) | |

| Phlegm | C⟶C | 0·065 | (0·0057–0·22) | 0·28 | (0·17–0·39) | 0·2 | (0·031 to 0·35) |

| C⟶A | 0·15 | (0·088–0·22) | 0·1 | (0·073–0·13) | −0·046 | (−0·13 to 0·022) | |

| A⟶C | 0·065 | (0·0091–0·18) | 0·17 | (0·073–0·32) | 0·11 | (−0·038 to 0·26) | |

| A⟶A | 0·061 | (0·025–0·12) | 0·078 | (0·043–0·12) | 0·016 | (−0·047 to 0·075) | |

| Runny nose | C⟶C | 0·076 | (0·003–0·29) | 0·25 | (0·16–0·36) | 0·17 | (−0·054 to 0·31) |

| C⟶A | 0·12 | (0·047–0·23) | 0·11 | (0·083–0·14) | −0·0078 | (−0·13 to 0·07) | |

| A⟶C | 0·23 | (0·052–0·46) | 0·1 | (0·04–0·19) | −0·12 | (−0·38 to 0·064) | |

| A⟶A | 0·061 | (0·019–0·13) | 0·074 | (0·044–0·11) | 0·013 | (−0·059 to 0·068) | |

| Sore throat | C⟶C | 0·3 | (0·17–0·45) | 0·18 | (0·088–0·3) | −0·11 | (−0·29 to 0·059) |

| C⟶A | 0·11 | (0·071–0·16) | 0·11 | (0·079–0·15) | 0·0013 | (−0·055 to 0·057) | |

| A⟶C | 0·18 | (0·065–0·36) | 0·081 | (0·021–0·19) | −0·1 | (−0·28 to 0·053) | |

| A⟶A | 0·085 | (0·043–0·14) | 0·062 | (0·033–0·11) | −0·022 | (−0·084 to 0·035) | |

CI, Credible interval; C, children, A, adults.

Posterior medians of the estimated transmission probabilities with corresponding 95% credible intervals (CI).

The arrows indicate the transmission pathways of influenza A with the donor on the left and the inheritor on the right; e.g. C⟶A represents a child-to-adult transmission.

For the model that assessed the effect of total number of symptoms, ignoring their type, the number of symptoms was not associated with infection risk, with non-significant effect sizes ranging from –0·5% to 0·6% depending on the age combinations.

There was moderate to strong support in favour of the no-symptom effect model compared to the models that allowed infectivity of those with symptoms to be arbitrarily higher (ΔDIC = 6.02) or twice (ΔDIC = 2.67) that of the asymptomatic individuals and to a model that considered the presence of multiple symptoms (ΔDIC = 57.57).

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that the presence of particular respiratory symptoms in influenza-infected individuals does not influence transmission probabilities, unless there is child-to-child transmission. Additionally, the number of symptoms present does not influence transmission probabilities, whether treated linearly or dichotomized (not shown). Taken together these results suggest that the absence of any particular symptoms in an influenza case, or the overall number of symptoms, might not be associated with a decreased risk of infectivity. This is an important finding, as several influential influenza A models assume that symptomatic cases are twice as infectious as asymptomatic cases [7, 8].

Our results, however, reveal that the presence of specific respiratory symptoms, notably phlegm or a cough with phlegm, in paediatric index cases increases their risk of transmitting influenza A to other children. The occurrence of this phenomenon may be explained by studies finding that children are more likely to spread infection to other household members, as well as the notion that children are more at risk of influenza A infection due to their increased susceptibility and higher rate of contact with potentially contaminated surfaces [15, 16]. It is possible that a more sophisticated analysis that pooled information between symptoms might illuminate the effect of other symptom presentations, but the lack of statistical significance for the models combining symptoms suggests otherwise, unless the sample size were substantially larger.

There are several assumptions underlying our study. Due to the study design we were unable to correct for pre-season antibody levels, or for the possibility that an asymptomatic case preceded the assumed index. However, other studies have shown that even after correcting for preseason HI titres, children have an elevated risk of household infection compared to adults [17], and the impact of prior immunity or cryptic indices is likely to impact the risk of infection but not the difference due to symptom presentation. We assumed that households are independent of each other, which is plausible in the absence of spatial clustering of recruited household, and that all secondary household cases obtained influenza from the index case.

The method of recruitment into this study has inherent selection bias, favouring index cases that have severe enough symptoms to seek medical assistance from their healthcare provider, and high enough viral loads to have a laboratory-confirmed case of influenza A. Index cases were recruited if they experienced the onset of at least two symptoms of acute respiratory illness, so the effect of any one symptom could be confounded by the presence of the other symptom whose presence co-determines enrolment eligibility. Despite these limitations, this study suggests that assumptions in modelling papers about the rate of asymptomatic transmission may need to be reviewed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

R.W. was supported by a New Colombo Plan scholarship from the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). K.P. and A.R.C. were supported by funding from the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Defence, and the National University Health System, all Singapore (grant nos. CDPHRG/0009/2014, NUHSR0/2013/142IH7N9104, PROJECT MODUS 9014100379). B.J.C. was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant U54 GM088558), a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. T11-705/14N), and a commissioned grant from the Health and Medical Research Fund from the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The original household trial in Hong Kong was supported by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant no. 1 U01 CI000439). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816002740.

click here to view supplementary material

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

B.J.C. reports receipt of research funding from Sanofi Pasteur and MedImmune Inc. for studies of influenza vaccination effectiveness.

REFERENCES

- 1.Briand S, Mounts A, Chamberland M. Challenges of global surveillance during an influenza pandemic. Public Health 2011; 125: 247–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y. China's public health-care system: facing the challenges. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2004; 82: 532–538. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson NM, et al. Strategies for containing an emerging influenza pandemic in Southeast Asia. Nature 2005; 437: 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee VJ, et al. Oseltamivir ring prophylaxis for containment of 2009 H1N1 influenza outbreaks. New England Journal of Medicine 2010; 362: 2166–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cauchemez S, et al. Estimating the impact of school closure on influenza transmission from Sentinel data. Nature 2008; 452: 750–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu JT, et al. School closure and mitigation of pandemic (H1N1) 2009, Hong Kong. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2010; 16: 538–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chao DL, et al. FluTE, a publicly available stochastic influenza epidemic simulation model. PLoS Computational Biology 2010; 6: e1000656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halloran ME, et al. Modeling targeted layered containment of an influenza pandemic in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 2008; 105: 4639–4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elveback LR, et al. An influenza simulation model for immunization studies. American Journal of Epidemiology 1976; 103: 152–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowling BJ, et al. Facemasks and hand hygiene to prevent influenza transmission in households: a cluster randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 2009; 151: 437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zambon M, et al. Diagnosis of influenza in the community: relationship of clinical diagnosis to confirmed virological, serologic, or molecular detection of influenza. Archives of Internal Medicine 2001; 161: 2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey NT. The Mathematical Theory of Infectious Diseases, 2nd edn. London: Hafner Press/Macmillan Publishing Co., 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson G, et al. Estimating parameters in stochastic compartmental models using Markov chain methods. Mathematical Medicine and Biology 1998; 15: 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelman A. Bayesian Data Analysis, 2nd edn. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viboud C, et al. Risk factors of influenza transmission in households. British Journal of General Practice 2004; 54: 684–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monto AS. Studies of the community and family: acute respiratory illness and infection. Epidemiologic Reviews 1994; 16: 351–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cauchemez S, et al. Determinants of influenza transmission in South East Asia: insights from a household cohort study in Vietnam. PLoS Pathogens 2014; 10: e1004310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816002740.

click here to view supplementary material