Abstract

Background:

Conservative/palliative (nondialysis) management is an option for some individuals for treatment of stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD). Little is known about these individuals treated with conservative care in the Canadian setting.

Objective:

To describe the characteristics of patients treated with conservative care for category G5 non-dialysis CKD in a Canadian context.

Design:

Retrospective chart review.

Setting:

Urban nephrology center.

Patients:

Patients with G5 non-dialysis CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate <15 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Measurements:

Baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics of conservative care follow-up, advanced care planning, and death.

Methods:

We undertook a descriptive analysis of individuals enrolled in a conservative care program between January 1, 2009, and June 30, 2015.

Results:

One hundred fifty-four patients were enrolled in the conservative care program. The mean age and standard deviation was 81.4 ± 9.0 years. The mean modified Charlson Comorbidity Index score was 3.4 ± 2.8. The median duration of conservative care participation was 11.5 months (interquartile range: 4-25). Six (3.9%) patients changed their modality to dialysis. One hundred three (66.9%) patients died during the study period. Within the deceased cohort, most (88.2%) patients completed at least some advanced care planning before death, and most (81.7%) of them died at their preferred place. Twenty-seven (26.7%) individuals died in hospital.

Limitations:

Single-center study with biases inherent to a retrospective study. Generalizability to non-Canadian settings may be limited.

Conclusions:

We found that individuals who chose conservative care were very old and did not have high levels of comorbidity. Few individuals who chose conservative care changed modality and accepted dialysis. The proportions of engagement in advanced care planning and of death in place of choice were high in this population. Death in hospital was uncommon in this population.

Keywords: conservative kidney management, palliative care, nondialysis care, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease

Abrégé

Contexte:

Les traitements conservateurs ou soins palliatifs (sans dialyse) constituent une option thérapeutique pour certaines personnes atteintes ‘d’insuffisance rénale chronique non-dialyse de catégorie 5 (IRC-ND). Toutefois, nous en savons peu au sujet des personnes inscrites à un programme de traitement conservateur dans le contexte canadien.

Objectif de l’étude:

Faire le portrait des patients atteints d’IRC-ND G5, sous traitement conservateur dans un contexte canadien.

Type d’étude:

Examen rétrospectif des dossiers médicaux.

Cadre de l’étude:

Un centre de néphrologie en milieu urbain.

Patients:

Des patients atteints d’IRC-ND G5 (débit de filtration glomérulaire estimé à moins de 15 ml/min/1,73 m2).

Mesures:

Les données démographiques initiales des patients, de même que les données cliniques de suivi du traitement conservateur, de planification des soins avancés et du décès.

Méthodologie:

Nous avons entrepris l’analyse descriptive des individus inscrits à un programme de traitement conservateur pour la période s’échelonnant du 1er janvier 2009 au 30 juin 2015.

Résultats:

Au total, 154 patients ont été inscrits dans un programme de traitement conservateur au cours de la période étudiée. L’âge moyen des patients était de 81,4 ans avec un écart-type de ± 9,0 ans. Le score moyen à l’index de comorbidité de Charlson modifié était de 3,4 ± 2,8 et la durée médiane de participation à un programme de traitement conservateur était de 11,5 mois (écart interquartile de 4,25). Au cours de la période étudiée, six patients (3,9%) sont passés du traitement conservateur à la dialyse et 103 patients (66,9%) sont décédés. Au sein de la cohorte de patients décédés, la grande majorité (88,2%) avait complété une partie des soins avancés planifiés avant le décès. De cette même cohorte, la plupart (81,7%) sont décédés où ils l’avaient choisi alors que 27 personnes (26,7%) sont décédées à l’hôpital.

Limites de l’étude:

L’étude s’est tenue au sein d’un seul centre hospitalier et comporte des biais inhérents attribuables à son modèle rétrospectif. De plus, la généralisation des résultats à des paramètres non canadiens peut être limitée.

Conclusions:

Nous avons constaté que les personnes qui avaient opté pour un traitement conservateur étaient très âgées et présentaient peu de comorbidités. Au cours de la période étudiée, quelques patients qui avaient choisi un traitement conservateur ont changé de modalité et accepté de passer à la dialyse. Nous avons également observé que l’engagement dans la planification des soins avancés et dans le choix de l’endroit où mourir était élevé au sein de cette population, alors que le décès à l’hôpital a été plutôt rare.

What was known before

Conservative care is an option for the treatment of advanced kidney disease in patients who do not wish to pursue renal replacement therapy.

What this adds

Comprehensive conservative care for patients with advanced kidney disease in a Canadian setting emphasizes advanced care planning and achieves a low risk of death in hospital. However, information technology infrastructure to prospectively study these patients is lacking.

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is common, affecting about 12.5% of Canadian adults,1 and is associated with an increased risk of comorbidity, prolonged hospitalization, and mortality.2 While older CKD patients are more likely to die than to progress to category G5 non-dialysis CKD,3-5 those patients who do develop G5 non-dialysis CKD must decide on a treatment modality, which may or may not include renal replacement therapy. As G5 non-dialysis CKD patients tend to feature a poor quality of life,6 and as dialysis may not be life-prolonging in older and comorbid G5 non-dialysis CKD patients,7-9 conservative care may be the preferred modality of treatment.

Conservative care, also known as palliative or supportive care, has been defined by the World Health Organization as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual,”10 which is also the definition recognized by Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO).11 Renal conservative care programs (CCPs) have emerged across the world with the goal of better addressing the end-of-life needs of advanced CKD patients.11,12 However, information about patients choosing conservative care for G5 non-dialysis CKD in a Canadian context is lacking. A characterization of this population would help guide the development of CCPs in Canada.

The objective of this study was to describe the characteristics of patients choosing conservative care for the treatment of G5 non-dialysis CKD in a Canadian context. We conducted a retrospective cohort study involving patients enrolled in a CCP in an urban Canadian nephrology center. We carried out a descriptive analysis based on patient characteristics and information regarding conservative care follow-up and death.

Methods

We designed a single-center retrospective cohort study to characterize renal patients enrolled in our CCP. It involved a chart review of patient records via an electronic data source. Adult patients with G5 non-dialysis CKD enrolled in our CCP between January 1, 2009, and June 30, 2015 in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, were included in this study. The onset date of G5 non-dialysis CKD was defined as the first of the two earliest consecutive estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) measurements at least three months apart of less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2, whereby all subsequent eGFR measurements remained less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2. We excluded patients whose eGFR was unknown or unmeasured.

The CCP was unique to this nephrology center. Patients were enrolled in the CCP after opting to forgo dialysis or after withdrawal of dialysis if they were not actively dying. The CCP involved patients who were referred by a nephrologist who had been previously following the patients at a multidisciplinary CKD clinic (generally involving patients with eGFRs below 30 mL/min/1.73 m2). A team with an interest in palliative care followed these patients, including a nephrologist with fellowship training in palliative medicine, an advanced care planning nurse clinician, and dedicated conservative care nurses (a full-time equivalent registered nurse divided between 2 individuals). A social worker and dietician were also available as needed. The CCP provided patient education about G5 non-dialysis CKD and about a trajectory without dialysis. Because patients chose enrollment into the program, the CCP provided active medical care that was specific to the goals and wishes of patients and their families. Symptom control was a priority. Patient follow-up was individualized and variable. Patients were followed in clinic and between clinic visits with phone calls and home visits. This program offered facilitated advanced care planning, which included a Goal of Care designation, though patients could have chosen to not engage in advanced care planning. It also offered bereavement follow-up with family members. Patients were encouraged to maintain relationships with their primary care providers.

Data were obtained from the prospective database of the Southern Alberta Renal Program.13 This database kept a record of patient demographics, blood work results, physician consultation notes, and multidisciplinary progress notes.

In this chart review, we sought to describe patient characteristics (eg, demographics, comorbidities, and laboratory results) at the onset of G5 non-dialysis CKD. We used the Charlson Comorbidity Index score for G5 non-dialysis CKD patients14 to describe the level of comorbidity burden. We considered a late referral to the multidisciplinary CKD clinic to be one that occurred after onset of or at ≤90 days before the onset of G5 non-dialysis CKD. We then described the details of CCP participation until the end of the study (eg, duration of follow-up and proportion of deceased patients by the end of the study). Finally, we characterized those patients who died while in the program, including details about advanced care planning and details of death. The details of death were already collected by the conservative care physician and nurses prior to this chart review. We determined the cause of death to be due to uremia if there was no other apparent cause of death and the course of illness included the typical constellation of symptoms associated with uremia (eg, encephalopathy, myoclonus, nausea, anorexia, and pruritus). The Dialysis Quality of Dying Apgar15,16 was used since the beginning of the CCP to rate the quality of death, out of a maximum score of 10. A higher score represented a higher quality of death. Despite the limited use of this tool in the literature,17 we employed the Dialysis Quality of Dying Apgar as it was the only such tool specific to G5 non-dialysis CKD patients available at the time of the program’s inception, and because of its ease of use.

The results of this chart review were analyzed descriptively in terms of mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range [IQR]), and proportions for numerical data. The University of Calgary’s Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board granted ethics approval for this study.

Results

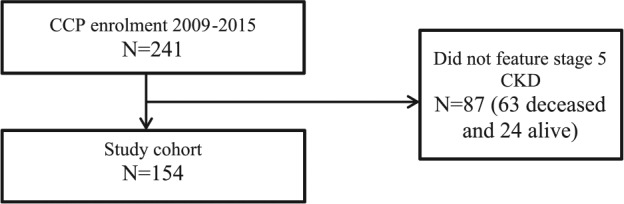

Among 241 patients enrolled in the CCP since the study start date, 63 deceased and 24 alive patients (by the end of the study date) did not meet our inclusion criteria as they had not reached G5 non-dialysis CKD. Therefore, we included 154 patients in this chart review for a descriptive analysis (Figure 1). We summarized the patients’ baseline characteristics at the time of study enrollment (onset of G5 non-dialysis CKD; Table 1). The mean age was 81.4 ± 9.0 years. The most common CKD etiologies were hypertension/ischemia and diabetes mellitus. About one-third of patients had a late referral to the multidisciplinary CKD clinic. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score was not high. Few patients previously underwent dialysis or kidney transplantation. The CKD lab parameters that were measured at the onset of G5 non-dialysis CKD are also listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study cohort.

Note. CCP = conservative care program; CKD = chronic kidney disease.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics in the Renal Conservative Care Program in Calgary, Alberta.

| Characteristic at G5 non-dialysis CKDa onset | All patients (n = 154) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 81.4 (9.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 71 (46.1) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 65 (42.2) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 27.8 (6.3) |

| CKD etiology, n (%)b | |

| Hypertension/ischemia | 81 (52.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 67 (43.5) |

| Reflux/obstruction | 13 (8.4) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 4 (2.6) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 1 (0.6) |

| Otherc | 17 (11.0) |

| Unknown | 15 (9.7) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score, mean (SD) | 3.4 (2.8) |

| Comorbidities, n (%)b | |

| Diabetes with end-organ damage | 69 (44.8) |

| Congestive heart failure | 40 (26.0) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 39 (25.3) |

| Myocardial infarction | 38 (24.7) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 32 (20.8) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 27 (17.5) |

| Dementia | 22 (14.3) |

| Diabetes without end-organ damage | 17 (11.0) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 12 (7.8) |

| Metastatic cancer | 7 (4.5) |

| Rheumatological disease | 7 (4.5) |

| Leukemia | 1 (0.6) |

| Lymphoma | 1 (0.6) |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 1 (0.6) |

| Late referral to multidisciplinary CKD clinic, n (%) | 54 (35.1) |

| Prior kidney transplant, n (%) | 1 (0.6) |

| Prior dialysis, n (%) | 8 (5.2) |

| Hemodialysis | 6 (75) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 2 (25) |

| Duration on dialysis, median (IQR), months | 10 (2.8-45.2) |

| Laboratory measurements, mean (SD) | |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 108 (16) |

| Phosphate, mmol/L | 1.5 (0.3) |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 2.4 (0.2) |

| Calcium phosphate product, mmol2/L2 | 3.7 (0.8) |

| Parathyroid hormone, ng/L | 187 (172) |

Note. CKD = chronic kidney disease; BMI = body mass index.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate <15 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The total percentages for CKD etiology and comorbidities exceeded 100% because some patients had more than one etiology and comorbidity.

Other etiologies include drug-induced, infection, and tubulointerstitial disease.

The details of participation in the CCP are summarized in Table 2. The median duration of participation in the CCP was 11.5 (IQR: 4-25) months. Advanced care planning was initiated before the end of the study in most patients. The majority of patients died in the CCP before the study end date, while few patients switched treatment modality from conservative care to dialysis.

Table 2.

Conservative Care Program Patient Outcomes.

| Outcome | All patients (n = 154) |

|---|---|

| Duration of participation, median (IQR), months | 11.5 (4-25) |

| Advanced care planning initiated before program exit, n (%) | 109 (70.8) |

| Goal of Care designation, n (%) | |

| Medical | 70 (45.4) |

| Comfort | 35 (22.7) |

| Resuscitative | 22 (14.3) |

| Unassigned | 27 (17.5) |

| Reason for CCP exit, n (%) | |

| Death | 103 (66.9) |

| Switch to dialysis | 6 (3.9) |

| End of study | 45 (29.2) |

Note. IQR = interquartile range; CCP = conservative care program.

Among patients who died during the study period, their outcomes are detailed in Table 3. Advanced care planning was more common in these patients. Most patients died in their preferred place of death, whereas about one-quarter of patients died in hospital (Table 4). The mean Dialysis Quality of Dying Apgar was high, and uremia was the commonest cause of death. Death outcomes based on early versus late referral to the multidisciplinary CKD clinic appeared to be similar.

Table 3.

Death Outcomes Following CCP Participation by Early and Late Referral to the Multidisciplinary CKD Clinic.a

| Death outcome | Deceased patients (n = 103, 67% of all patients) | Late referral (n = 36/103, 35% of deceased patients) | Early referral (n = 67/103, 65% of deceased patients) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced care planning initiated before program exit, n (%)b | 82 (88.2) | 30 (93.8) | 52 (85.2) |

| Known preferred place of death, n (%) | 82 (79.6) | 31 (86.1) | 51 (76.1) |

| Match between preferred and actual place of death, %c | 81.7 | 83.9 | 80.4 |

| Death in hospital, n (%)d | 27 (26.7) | 9 (25.0) | 18 (27.7) |

| Dialysis Quality of Dying Apgar, mean (SD) | 8.9 (1.0) | 9.0 (1.0) | 9.0 (1.1) |

| Death due to uremia, n (%)e | 52 (63.4) | 19 (61.3) | 33 (64.7) |

| Bereavement follow-up for family members, n (%)f | 70 (71.4) | 27 (79.4) | 43 (67.2) |

Note. CCP = conservative care program; CKD = chronic kidney disease.

Early referral: at >90 days before onset of G5 non-dialysis CKD. Late referral: after onset of or at ≤90 days before onset of G5 non-dialysis CKD.

Due to missing data, the proportions for advanced care planning initiation are with respect to the following sample sizes: deceased patients (n = 93), late referral (n = 32), and early referral (n = 61).

When both actual and preferred places of death were known.

Due to missing data, the proportions for death in hospital are with respect to the following sample sizes: deceased patients (n = 101), late referral (n = 36), and early referral (n = 65).

Due to missing data, the proportions for death due to uremia are with respect to the following sample sizes: deceased patients (n = 82), late referral (n = 31), and early referral (n = 51).

Due to missing data, the proportions for bereavement follow-up are with respect to the following sample sizes: deceased patients (n = 98), late referral (n = 34), and early referral (n = 64).

Table 4.

Place of Death Among Deceased Patients According to Their Preferred Place of Death (n = 103).

| Preferred place of death | Place of death (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home/LTC | Hospice | Hospital | Othera | Unknown | |

| Known (n = 82/103, 79.6% of deceased patients) | |||||

| Home/LTC (n = 33), n (%) | 21 (63.6) | 6 (18.2) | 6 (18.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Hospice (n = 26), n (%) | 0 | 23 (88.5) | 2 (7.7) | 1 (3.8) | 0 |

| Hospital (n = 6), n (%) | 0 | 0 | 6 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Othera (n = 17), n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 (100) | 0 |

| Unknown (n = 21/103, 20.3% of deceased patients), n (%) | 0 | 3 (14.3) | 13 (61.9) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (9.5) |

Note. LTC = long-term care facility.

Other places of death included, for example, a friend or relative’s home.

Discussion

A review of patients who chose conservative care in this Canadian nephrology center revealed an older cohort with a low comorbidity index. Most participants were followed in the multidisciplinary CKD clinic for at least 90 days prior to G5 non-dialysis CKD onset. Few of them previously received renal replacement therapy or switched treatment modality from conservative care to dialysis. Their CKD laboratory parameters were reasonably well managed. The majority of patients engaged in advanced care planning. Overall, most deaths occurred in the place of choice, and death in hospital was relatively uncommon. The quality of death was high.

Although Canadian dialysis patients are generally also older,18 patients receiving dialysis have reportedly demonstrated different outcomes compared with patients enrolled in our CCP. Unlike our conservative care cohort, other G5 non-dialysis CKD patients receive delayed or inadequate end-of-life planning and palliative care service availability.19-22 The patients in our CCP had a lower proportion of in-hospital death compared with dialysis patients (eg, 44.8% in an American study,23 66% in an Australian study,24 and 74% in a Canadian study25) and with the general population in Alberta and Canada (57.5% and 63.4%, respectively26). Although we did not measure the frequency of procedures and hospitalization, other studies found that being on dialysis results in more hospitalization.27 Moreover, although we did not look for an association between comorbidity burden and survival, studies have reported that comorbidity increases the risk of death in dialysis28 and nondialysis29 advanced CKD patients. To this effect, it has been suggested that dialysis is not life-prolonging compared with conservative care in comorbid older patients.30

The outcomes of our CCP suggest that it has been successful in terms of death in place of choice and quality of death. Previous studies have reported that provision of conservative care should emphasize patient preference,31,32 include a multidisciplinary team,33,34 involve shared decision making,22,34,35 and align with local practices and community needs.36 These characteristics of health care delivery hence warrant organized CCPs, such as the case presented in this study, which featured success in allowing most patients to die in their preferred place of death. With a high proportion of bereavement follow-up with family members, we were able to address the experience of grief.37 We were also successful in providing a high quality of death to the deceased cohort. Furthermore, as seen elsewhere, our CCP patients commonly featured survival beyond a year after enrollment and seldom switched to dialysis.24

This study featured several limitations. The starting eGFR for patients at the time of CCP enrollment was heterogeneous. For patients who were followed in the CCP prior to G5 non-dialysis CKD onset, we counted CCP enrollment in this study once the eGFR fell below 15 mL/min/1.73 m2. However, other patients were referred to the CCP with lower starting eGFRs. As the data were retrieved from a single data source (PARIS software), it was dependent on the completeness of the information entered in the database (inconsistent degree of patient details among online records). This study is also limited by its retrospective design, with inherent biases in patient selection, as well as its generalizability (single-center Canadian study). Still, it represents an important example of comprehensive conservative care in a Canadian setting where such published experiences are scarce.

The results of this study will help guide the development of other CCPs in Canada. These programs are needed not only in centers where advanced kidney disease is managed by nephrologists but also for the large number of such patients managed by their primary care physicians.38 However, obtaining this information by way of chart review was cumbersome, signifying that renal information systems for conservative care are lacking. Information technology infrastructure needs to be developed for renal CCPs that will allow for patient outcomes to be measured on a systematic and prospective basis. Such infrastructure would facilitate research of this population that may be stronger methodologically, including prospective and larger studies (eg, multicentered when such infrastructure is adopted by other centers). It would also allow us to observe trends in patient outcomes over time. In the future, we would like to also collect and report information on the frequency of procedures and hospitalization, the rate of renal function decline, performance status, frailty, and symptoms. This study underlines, furthermore, the need for a validated tool for measuring the quality of death in G5 non-dialysis CKD patients.39

Conclusion

This report of advanced CKD patients enrolled in a CCP in an urban Canadian center is the first one in Canada to describe their demographic and clinical characteristics as well as death outcomes. These patients were not generally very comorbid and chose palliative care without ever having received dialysis. They engaged in advanced care planning and featured favorable outcomes at the time of death. A better understanding of these patients and how they are managed provides insight into potential improvements in health services delivery for this patient population. However, information technology infrastructure is needed for renal CCPs to facilitate the prospective measurement of patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the CCP nurses Lisa Blacklock, Pat Holmes, and Ruth DeBoer for their contributions to the program.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: The University of Calgary’s Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board has approved this research study.

Consent for Publication: Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials: The original data from the chart review will not be made available, as we did not acquire ethics approval to do so.

Author Contributions: FBK obtained ethics approval, performed the chart review, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. HT-T reviewed the ethics application, helped with the data analysis, and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. CT conceived the study, reviewed the ethics application, guided the design of the chart review, helped with the data analysis, and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Arora P, Vasa P, Brenner D, et al. Prevalence estimates of chronic kidney disease in Canada: results of a nationally representative survey. CMAJ. 2013;185:E417-E423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jassal SV, Trpeski L, Zhu N, et al. Changes in survival among elderly patients initiating dialysis from 1990 to 1999. CMAJ. 2007;177:1033-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dalrymple LS, Katz R, Kestenbaum B, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risk of end-stage renal disease versus death. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:379-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O’Hare AM, Choi AI, Bertenthal D, et al. Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2758-2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM, Brown JB, Smith DH. Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organization. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:659-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saini T, Murtagh FE, Dupont PJ, McKinnon PM, Hatfield P, Saunders Y. Comparative pilot study of symptoms and quality of life in cancer patients and patients with end stage renal disease. Palliat Med. 2006;20:631-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Foote C, Kotwal S, Gallagher M, Cass A, Brown M, Jardine M. Survival outcomes of supportive care versus dialysis therapies for elderly patients with end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2016;21:241-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Verberne WR, Geers AB, Jellema WT, Vincent HH, van Delden JJ, Bos WJ. Comparative survival among older adults with advanced kidney disease managed conservatively versus with dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:633-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, et al. Survival of elderly patients with G5 non-dialysis CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:1608-1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Published 2016. Accessed October 9, 2016.

- 11. Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:195-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haras MS. Planning for a good death: a neglected but essential part of ESRD care. Nephrol Nurs J. 2008;35:451-458, 483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manns BJ, Mortis GP, Taub KJ, McLaughlin K, Donaldson C, Ghali WA. The Southern Alberta Renal Program database: a prototype for patient management and research initiatives. Clin Invest Med. 2001;24:164-170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Quan H, Ghali WA. Adapting the Charlson Comorbidity Index for use in patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:125-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cohen LM, Germain MJ. Measuring quality of dying in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2004;17:376-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohen LM, Poppel DM, Cohn GM, Reiter GS. A very good death: measuring quality of dying in end-stage renal disease. J Palliat Med. 2001;4:167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McAdoo SP, Brown EA, Chesser AM, Farrington K, Salisbury EM; pan-Thames renal audit group. Measuring the quality of end of life management in patients with advanced kidney disease: results from the pan-Thames renal audit group. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1548-1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian organ replacement register annual report: Treatment of end-stage organ failure in Canada, 2003 to 2012. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berzoff J, Swantkowski J, Cohen LM. Developing a renal supportive care team from the voices of patients, families, and palliative care staff. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6:133-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Siegler EL, Del Monte ML, Rosati RJ, von Gunten CF. What role should the nephrologist play in the provision of palliative care? J Palliat Med. 2002;5:759-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burns A, Carson R. Maximum conservative management: a worthwhile treatment for elderly patients with renal failure who choose not to undergo dialysis. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:1245-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tonkin-Crine S, Okamoto I, Leydon GM, et al. Understanding by older patients of dialysis and conservative management for chronic kidney failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:443-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM. Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:661-663; discussion 663-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morton RL, Webster AC, McGeechan K, et al. Conservative management and end-of-life care in an Australian Cohort with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:2195-2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ontario Renal Network. 2016-2019 Palliative Care Report: recommendations towards an approach to chronic kidney disease. Toronto, Ontario: Cancer Care Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Statistics Canada. Table 102-0509: deaths in hospital and elsewhere, Canada, provinces and territories—annual. Canadian Socio-Economic Information Management System; http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1020509. Published 2015. Accessed 11 October, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, Burns A. Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1611-1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lamping DL, Constantinovici N, Roderick P, et al. Clinical outcomes, quality of life, and costs in the North Thames Dialysis Study of elderly people on dialysis: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2000;356:1543-1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wong CF, McCarthy M, Howse ML, Williams PS. Factors affecting survival in advanced chronic kidney disease patients who choose not to receive dialysis. Ren Fail. 2007;29:653-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. O’Connor NR, Kumar P. Conservative management of end-stage renal disease without dialysis: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:228-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnston S, Noble H. Factors influencing patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease to opt for conservative management: a practitioner research study. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:1215-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van de Luijtgaarden MW, Noordzij M, van Biesen W, et al. Conservative care in Europe—nephrologists’ experience with the decision not to start renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:2604-2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Noble H, Rees K. Caring for people who are dying on renal wards: a retrospective study. EDTNA ERCA J. 2006;32:89-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guideline recommendations and their rationales for the treatment of adult patients. In: Renal Physicians Association, ed. Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of Withdrawal From Dialysis. 2nd ed. Rockville, MD: Renal Physicians Association; 2010:39-92. https://www.guideline.gov/summaries/summary/24176/guideline-recommendations-and-their-rationales-for-the-treatment-of-adult-patients-in-shared-decisionmaking-in-the-appropriate-initiation-of-and-withdrawal-from-dialysis-2nd-edition [Google Scholar]

- 35. Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, et al. ; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes. Executive summary of the KDIGO controversies conference on supportive care in chronic kidney disease: developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney Int. 2015;88:447-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fried O. Palliative care for patients with end-stage renal failure: reflections from Central Australia. Palliat Med. 2003;17:514-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bartlow B. What, me grieve? Grieving and bereavement in daily dialysis practice. Hemodial Int. 2006;10(suppl 2):S46-S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hemmelgarn BR, James MT, Manns BJ, et al. ; Alberta Kidney Disease Network. Rates of treated and untreated kidney failure in older vs younger adults. JAMA. 2012;307:2507-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hales S, Zimmermann C, Rodin G. Review: the quality of dying and death: a systematic review of measures. Palliat Med. 2010;24:127-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]